Abstract

Pediatric skulls change rapidly in size and shape during development, especially for children up to 8 years of age. This project was developed to address the gap in understanding of the three-dimensional growth parameters of the human skull during this period and the impact these growth patterns have on fontanelle closure and suture formation. This study offers novel data on the dynamic changes in the anatomy of the skull with the intention of providing better guidance for pediatric surgical care. Craniometric landmarks defined on three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions were used to map skull development in children aged 0 to 8 years old. A total of 364 datasets were analyzed and statistically representative 3D skulls with anatomical craniometric features such as head shape, bone size, suture and fontanelle closure time were generated for 17 age groups spanning birth to 8 years of age to provide a comprehensive neuroanatomical understanding of how the pediatric skull changes over time. This study indicates that the cranial bones follow a non-linear growth pattern, with the occipital and frontal bones driving the directionality of fontanelle closure and delivers a 3D visualization of the developmental characteristics of the skull providing a landmark resource for understanding the growth dynamics of the human skull. While clinical measurements remain valid approaches for the planning of surgical interventions, these 3D models may provide a more accurate planning paradigm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formation of the human skull is a complex process that begins during the fourth week of development and is completed during adulthood1,2. The calvaria, or cranial vault, encompasses the brain, cranial nerves, meninges, blood vessels, and cerebrospinal fluid within the cranial cavity. Ossification of the skull bones starts at 5 to 6 weeks of gestation and occurs both intramembranously and endochondrally, and the junction of the osteogenic fronts is sutured by 16 weeks of gestation3,4,5,6.

The continuous development of the calvaria creates significant differences in skull sizes and patterns between infants and children at different ages. Most vault bones are flat and consist of two tables (or plates) of compact bone enclosing a thin layer called the diploe, a site of hematopoiesis in young individuals. The diploe is of considerable importance in cranial bone grafting, where the two tables can be split to produce an autograft7,8,9. At birth, the calvaria is large relative to other skeletal structures; this reflects the cerebral maturation process which is the primary factor for early growth of the newborn cranial vault10.

In newborns, ossification of the calvaria is incomplete. The bones are still united by fibrous tissue and may be unilaminar. The fontanelles and width of the sutures allow bones of the cranial vault to overlap during birth7,8,9. As the skull bones enlarge, the fontanelles are reduced to a narrow layer of fibrous connective tissue that sutures the bony plates together. The fibrous membrane that forms the skull remains unossified at the six angles of the parietal bones, producing six fontanelles: two unpaired midlines—the anterior fontanelle and posterior fontanelle—and two lateral pairs—the sphenoidal (anterolateral) fontanelles and mastoidal (posterolateral) fontanelles. Cranial sutures eventually ossify through the fusion of two adjacent bones into a single bone, also called synostosis. Most fontanelles are expected to be closed by 24 months, including the anterior fontanelle, posterior fontanelle, as well as the metopic suture11,12,13,14.

Unlike endochondral growth plates which expand through chondrocyte hypertrophy, sutures do not have intrinsic growth potential. Rather, they produce new bone at the sutural edges of the bone fronts in response to external stimuli such as signals arising from the expanding lobes suggesting that the growth of the cranial vault is coordinated with the growth of the brain. The mechanical forces that modulate bone growth at the sutures include underlying brain growth, interactions at the dural-calvaria interface, and external factors such as compression causing bone reabsorption along the suture rather than suture fusion3,6. Thus, the margins of adjacent bones of a suture are characterized by numerous projections that interlock and form a serrated jigsaw appearance. To function as growth sites, sutures must remain patent while still allowing bone formation at the edges. Premature fusion of cranial sutures, also called craniosynostosis, prevents further bone formation and restricts expansive growth of the underlying neurocranium, leading to abnormal compensatory morphogenesis6,15,16.

Surprisingly, little is known about what happens to the skull during the first 8 years of life from a three-dimensional (3D) perspective. There are studies that show development of the pediatric skull in 3D that focus on bone thickness changes from 0 to 3 years of age, as well as craniofacial models for the first year of life that depict cranial shape and size predictions based on 3D computed tomography (CT) scan reconstructions specifically for application in the clinical management of craniosynostosis17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. However, skull development including cranial shape and size through the first 8 years of life is still relatively unknown. The cranium undergoes greater changes in form during the first years of life due to brain development, bone growth, and suture closure, with the skull approaching the size of an adult’s at approximately 7 years of age despite some sutures at the base of the skull continuing to change into adulthood1,5,13,17,18,28,29.

Remarkably, the craniometric points used for surgical access in children, such as the freehand placement of a ventricular catheter, are still based on craniometric studies of the adult skull30,31,32,33,34. While using adult craniometric references for the treatment of children is done out of necessity and limited resources, using adult measurements has the potential for inaccuracy since the relationships between brain structures and skull landmarks are not necessarily the same in children as in adults. Recently, Liang et al.19 reported that cranial shape is significantly associated with cranial volume; however, this association explains only 21% of the variance in cranial shape. Other factors that might account for skull allometry and explain the remaining 79% of shape variance are still unknown.

This study’s main objective is to provide a 3D representation of the developmental skull anatomy of children from birth to 8 years using 3D CT reconstructions and the identification of linear landmarks on each bone that comprises the calvarium. We aim to demonstrate the timing and directionality of suture and fontanelle closure, alterations in cranial size and shape, and individual bone growth over time. Additionally, we seek to validate the impact of individual bone growth on the changes in intracranial volume and establish a correlation between the changes and cranial allometry, to provide more comprehensive and accurate resources for clinical decision-making.

Methodology

Study design

A qualitative retrospective analysis of 3D CT images from cross-sectional pediatric datasets ranging in age from birth to 8 years was performed. Each dataset contained 3D CT reconstructions for bone and soft structures in sagittal, coronal, and axial views for an individual child’s skull. The datasets were obtained from Beneficencia Portuguesa (BP) hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and the British Columbia Children’s Hospital (BCCH) in Vancouver, Canada. This study was conducted under the approval of the BCCH Clinical Research Ethics Board (H18-02452) and the Simon Fraser University Research Ethics Board (2018s0646), both with the requirements of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2, 2018), as well as the BP Hospital Research Ethical Board (2.743.576) in accordance with the Brazilian Ministry of Health Research Ethicals Board (CNS no 466/2012) requirements following the Declaration of Helsinki. This study’s use of retrospective imaging datasets was approved with accordance to the requirements for consent as stated in TCPS 2 Articles 3.1 to 3.5. All images were deidentified and a number was assigned to replace the patient’s identity. Other details of these individuals (i.e., ethnicity and body weight) were not available for this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Radiographic image datasets were obtained from both BP and BCCH and assessed for presence of trauma, concern for non-accidental trauma, headache, seizure, change in neurological status or level of consciousness, and abnormalities in neurological examination findings. Datasets from children aged 1 day to 8 years with normal brain development and normal cranial CT scan images taken between 2007 and 2017 were included.

The following conditions represented exclusion criteria for study subjects: prematurity, hydrocephalus (treated and untreated), intracranial tumors or mass lesions, intracranial arachnoid cysts, intracranial hemorrhage, craniosynostosis, skeletal diseases that affected the calvaria (e.g., osteogenesis imperfecta), growth related syndromes (e.g., congenital hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism), congenital ischemic encephalopathy, skull fractures affecting midline calvarial measurements, positional plagiocephaly, and congenital deformities of the brain and skull, including any genetic syndrome. It is well described in the literature that sexual differences in cranial growth become more pronounced after puberty19 therefore, this study did not analyze skull variation based on sex.

The Brazilian sample comprised a total of 224 3D CT datasets collected from BP. Of these 224 datasets, 37 were excluded during the second review due to hydrocephalus (10), intraventricular hemorrhage (4), fracture (2), postoperative alterations (8), craniosynostosis (3), subdural hematoma (2), ischemia (1), schizencephaly (1), or duplicated images (6). The Canadian sample included a total of 221 datasets collected from BCCH. Of these 221 datasets, 13 were excluded during the second review due to images missing the cranial base (7), movement artifacts (1), fracture (1), or images showing only the cranial base (4). After the first data analysis, 31 datasets (BP-10, BCCH-21) were excluded due to low image resolution, totalling 364 datasets that met inclusion criteria to be used in the study. The number of datasets per age group is depicted in Table 1.

Data collection

The 3D CT images were acquired by multislice detector equipment through volumetric readings with a slice thickness between 0.5 and 0.6 mm using reconstruction algorithms for bones and soft structures. Equipment used included Siemens Definition Plus (64 × 2 channels), Toshiba Aquilion 64 (64 channels), General Electric VCT (64 channels), and General Electric Lightspeed Pro 16 (16 channels). The datasets were in the neuroimaging informatics technology initiative (NIFTI) file format.

The study subjects were stratified by age from the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) at both BP and BCCH. The filters used in the image search were age, CT head without contrast, and date of exam. All images were deidentified and a number was assigned to replace the patient’s identity. A computer algorithm calculated the patient’s age according to the date of birth and the exam date and datasets were categorized into 17 groups according to the patient’s age at the exam. The age groups were noted in months. All measurements were recorded by the same researcher to minimize consistency errors in the methodology.

Modelling process

The datasets were analyzed and converted into 3D models using the program 3D Slicer, a free, open-source software designed for visualization of biomedical imaging (https://www.slicer.org/)35,36. After loading the 364 NIFTI datasets into 3D Slicer, a minimum image voxel threshold of 100 was applied to extract the skulls with the 3D Slicer “Segment Editor” module37. Stray and detached segmentations were eliminated using the “Islands” effect and the resulting skull segmentations were saved as skull models for visualization and postprocessed using the 3D Slicer “Maximal Intensity Projection” tool, which allowed for the clear identification of landmarks on each model35. Please find the complete list of landmarks used in this study in the supplemental information section.(S1-Complete list of landmarks).

Intracranial volume calculation

The intracranial volume (ICV) of 364 datasets was calculated in cubic centimetres (cm3) using the 3D Slicer “Wrap Solidify” effect which, when applied to the skull segmentation models automatically fills in the volume of the skull models. To obtain volumetric information of the segmentation model, we used the 3D Slicer “Segment Statistics” module to calculate ICV for each dataset. This method was validated by Harkey et al.38 The ICV of 364 datasets were plotted against age in months. To facilitate comparative analysis, the ICV data were further divided into 17 age groups (monthly for the first year of life, then clusters from 18 to 24 months, 24 to 48 months, 48 to 72 months, and 72 to 96 months). The mean ICV values within the 95% confidence interval were selected to represent the average skull size of their respective age group. We compared our best fit plot for ICV with the normative values used by the World Health Organization39 for head circumference to validate the ICV calculation model. This comparison confirmed that the calculated ICV values provided a good representation of healthy development for each age group analyzed.

A skull growth curve was generated by plotting the ICV by age and then calculating a power best-fit curve (Fig. 1). Frontal, parietal, and temporal bones are present on both sides of the skull, so a Student’s t-test was performed to determine whether there was a significant difference in bone perimeter between left and right frontal, parietal, and temporal bones (p = 0.78, 0.71, and 0.51, respectively). Since there was no significant difference between the left and right bones, the datasets were combined.

We sought to identify which cranial dimensions have the greatest effect on cranial volume in each age group analyzed. The metrics we first analyzed were Towering Index (TI) as a measure of vertical elongation in the pediatric skull as described by Pindrik et al.40 (TI = ratio of maximum distance between the glabella and opisthocranion (GOPD – curve(arc)) and the glabella-opisthocranion diameter (GOPP – Line)) and Cephalic Index (CI) as a measure of antero-posterior and latero-lateral cranial dimensions as described Cohen et al.41 (CI = maximum cranial width / maximum cranial length x 100%). Anthropometric cranial measurements such as TI and CI are essential for clinical assessment of skull dysmorphism and for identifying brain growth abnormalities. To validate the proposed model, our results for TI and CI were compared with the normative values proposed by Pindrik et al. and Cohen et al., respectively, which suggest that the cohort was an appropriate representation of skull development of the healthy 0- to 8-year-old population. (supplemental Table S2) We used the statistical computing software R to perform an ANOVA to evaluate the effect of age, TI, and CI on cranial volume, as well as the interactions between these three variables.

Both TI and CI describe the three-dimensional shape of the skull and the measurements used to determine these indices are in multiple cardinal directions. Using these multidirectional values to analyze cranial volume presents a concern because any changes measured cannot be related to a specific cardinal direction with certainty; when TI increases, it is unclear if the direction of increase occurs predominantly in the inferior-superior direction or the anterior-posterior direction or both. To address this concern, we conducted a subsequent analysis on the influence of the glabella-opisthocranion diameter (GOPD), biparietal diameter (BIPD), and the distance from the external acoustic meatus to the vertex (EAV) because each of these measurements are associated with a single cardinal direction. GOPD represents the anterior-posterior length of the skull, BIPD represents the latero-lateral length, and EAV represents the inferior superior length. (Fig. 2) An ANOVA evaluating the effect of age, GOPD, BIPD, and EAV on ICV was performed.

Landmarks and measurements used to analyze the correlation of cranial dimensions with cranial volume. GOPD = glabella-opisthocranion diameter (anterior-posterior); BIPD= biparietal diameter (latero-lateral); GOPP = glabella-opisthocranion perimeter (head circumference); EAV = External Acoustic Meatus – Vertex (inferior – superior).

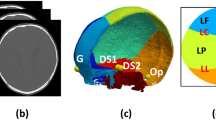

Landmarks on the skull surfaces and suture-bone boundaries. Note:This picture shows a screenshot from 3D Slicer showing the markups (in pink) on the 2-month-old age group 3D model on the lambdoid and sagittal sutures. All the markups (represented here by LLSD-06 and LLSD-08) were placed on the 3D model (a) with simultaneous verification on 2D CT scans in axial (b), coronal (c), and sagittal (d) views with the best visualization of the bones’ sutures, inner and outer tables.

Bone perimeter calculation

Next, we calculated the perimeters of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones of all 17 skull models by manually placing consecutive fiducial markers on the surface of the skull using the 3D Slicer “Fiducial” tool. To ensure consistency in this process, all 17 skull models were annotated by the same researcher. Additionally, we ensured accuracy in the placement of fiducial markers by cross-referencing the markups on the 3D models with their respective two-dimensional (2D) CT regular bone images. (Fig. 3) Cross sections of CT scans display bone edges and the location of the inner and outer tables of the skull bones more clearly than 3D reconstructions, so this comparison with the 2D CT regular bone images allowed us to place the fiducial marker more precisely on the chosen landmark. Each fiducial marker was named after the mapped structure followed by a number (e.g., the first fiducial on the left parietal bone dimension is named LPBD_1) and placed at a random distance apart to allow an outline of the cranial bones being consistent with the number of fiducials in the bilateral bones’ perimeters marking (e.g. parietal bones). The fiducial markers were analyzed using two Python scripts: the first to analyze the width of each suture and the second to calculate the perimeter of each skull bone in the 3D model.

To determine the bone perimeter, the Euclidean distance between successive pairs of points (i.e., distance between the first and second points, the second and third points, etc.) as proposed by Li et al.42 was calculated using the following equation where (x1,y1,z1) represents the 3D location of the first point in the pair and (x2,y2,z2) represents the location of the second point in the pair.

These distances were then summed to determine the total curve length or total perimeter for each skull bone.

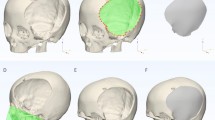

Cranial bone perimeter growth rate. Note: This figure shows the rapid growth rate of the occipital bone during the first 8 months of life, followed by frontal and parietal bones. (a) bone perimeter growth rate from birth to 84 months; (b) bone’s perimeter growth rate from birth to 12 months showing the steady growth rate of the occipital bone.

To illustrate the changes in skull size and shape with increasing age, the perimeter of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones were measured. (Fig. 4) We compared the perimeter points of each bone by age group using a mathematical model. First, we assumed that both left and right pairs of bones grew at approximately the same rate based on the Student’s t-test described in Sect. 2.5. This assumption allowed us to calculate the average bone perimeter of the left and right frontal, parietal, and temporal bones; the occipital bone is unpaired and thus, the occipital bone perimeter was not adjusted. The bone perimeter values for each age group were calculated by dividing the average perimeter at each time point by the perimeter at 84 months. The 84-month time point was chosen for this calculation because there was no significant growth between 84 and 96 months, and it represents the largest bone perimeter measurement within the scope of this study. The perimeter values show that the growth curve is logarithmic; therefore, we inferred that a logarithmic model is appropriate for the data.

One of the challenges we encountered when calculating the growth rate from raw data was due to the fact that the model for each age group comprised datasets from different individuals and not datasets from the same cohort of individuals at multiple timepoints. The main consequence of this was the size differences between individuals. For example, the head circumference of the 6-month-old group was 44.6 cm whereas the head circumference for the 7-, 8-, and 9-month-old groups were 43.9 cm, 42.6 cm, and 40.6 cm, respectively. Even though the overall head circumference of the 6-month-old group was greater than that of the following three age groups, we assumed that the head circumference of the individual subjects comprising the 6-month-old group would have shown an increase in head circumference if they returned for imaging at the next three timepoints because all datasets met the inclusion criteria of normal brain development and normal cranial CT scans. This explains why most of our included datasets are above the 50th percentile but within a 95% confidence interval for normal development. To account for this sample error, the instantaneous growth rate of each of the cranial bones was determined analytically by calculating the first derivative of each model equation. (Fig. 5)

Suture and fontanelle closure analysis

Here we will elaborate on the analysis of the coronal, sagittal, lambdoid, metopic, sphenofrontal, and squamous sutures briefly described in Sect. 2.6. Fiducial markers were manually placed on the reconstructed 3D skull perpendicular to the tangent plane of the skull surface along the edge of each skull bone using 2D CT regular bone images to cross-reference and ensure accuracy of placement. These fiducial markers were placed as subsequent pairs on either side of the suture on different bones, rather than placing subsequent fiducial markers for an individual skull bone to ensure that the paired fiducial markers were aligned for an accurate suture analysis. For example, when annotating the bone edges on either side of the lambdoid suture, a fiducial marker named LSD_1 (where LSD stands for lambdoid suture distance) was placed on one bone and another fiducial marker named LSD_2 was placed on the second bone directly opposite to LSD_1 across the suture. In this case, LSD_1 and LSD_2 form a pair of fiducial markers (Fig. 3).

The Python script calculated the Euclidean distance between a pair of points on opposite sides of the suture between two skull bones to generate the average width of each suture along its length. These suture widths were compared between consecutive age groups to analyze how quickly the sutures closed and, by extension, how quickly the bones grew. Descriptive analysis of the closure of the sutures was performed based on the 3D CT reconstructions and results were compared with those in the current literature. We categorized sutures according to the visual classification of suture closure using the seven stages proposed by Fan et al.13 in a cross-section of CT images.

Directionality of suture and fontanelle closure

Due to the non-linearity of the cranial bone growth, we sought to describe the directionality of closure for the fontanelles with respect to the growth of the surrounding cranial bones. We first hypothesized that cranial bone perimeter and the total width of the surrounding sutures were negatively correlated. This hypothesis was based on the assumption that as the cranial bones grew outward (increasing perimeter), the surrounding sutures would shrink in size. Since the bones grew at different rates, we expected the magnitude of the correlation would follow a similar pattern to each bone’s growth rate. We also hypothesized that the cranial bones that grew at a faster rate would have a negative Pearson correlation of greater magnitude than the bones that grew more slowly.

To determine the relationship between bone perimeter and age, a linear line of best fit was attempted; however, the R squared values did not show a linear relationship. Following the work of Liang et al., we next attempted to identify the type of relationship between age and bone perimeter through linearizing transformations. Linearization by log-log transformation was performed on the dataset for each of the bones and is presented in Fig. 5. To evaluate the relationship between bone perimeter growth and age, Student’s t-test was performed on the log-log transformed data for the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones.

The posterior fontanelle is surrounded by the sagittal suture anteriorly and the two lambdoid sutures postero-laterally. Therefore, we assumed that the total length of the three sutures surrounding the posterior fontanelle was equal to double the length of the right lambdoid suture plus the length of the sagittal suture. To compare the contribution growth of the occipital and parietal bones have on the closure of the posterior fontanelle, we calculated two Pearson correlation coefficients (r). The first describes the linear correlation between the perimeter of the occipital bone from 0 to 84 months with the total length of surrounding sutures. The second describes the linear correlation between the average perimeter of the parietal bones to the total length of the surrounding sutures. We performed Student’s t tests for each correlation to confirm that the calculated r values were statistically different from no correlation (i.e., r = 0). This process was repeated for the anterior fontanelle. Figures 6 and 7 depict the sutures and fontanelles analyzed and the relationship between the cranial bone perimeters and the total length of the surrounding sutures for the posterior and anterior fontanelles, respectively.

Results & discussion

Intracranial volume

The greatest increase in ICV was observed in the first year of life. The IVC increased by approximately 350.0 cm3 between 0 and 12 months, reaching an average of 1100.3 cm3 (ranging from 502.4 to 1434.0 cm3). The ICV continued to increase until 3 years of age at an average of 70.3 cm3 per year, reaching an average cranial volume of 1254.9 cm3 (ranging from 918.7 to 1444.9 cm3) at 3 years of age. This period of increased growth of the skull implies that the child’s brain also develops at an increased rate, which is supported by the theory that brain growth-related intracranial pressure is crucial for triggering growth mechanisms. From 3 to 8 years of age, cranial volume growth slows by approximately 50% at an average rate of 35.0 cm3 per year (ranging from 31.0 to 38.0 cm3) until it reaches cranial volume typical of an adult, with an average of 1417.8 cm3 (ranging from 1156.0 to 1717.9 cm3).

The ICV values for the 17 age groups are within remarkable agreement with the data presented by Cronin et al.16, except for the age groups from 0 to 3 months which displayed a larger ICV (813.2 cm3). Cronin et al. analyzed ICV from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 24 subjects between ages 0 and 3 months. The difference in ICV values may be explained by the differences in imaging and measurement techniques or the different defined age ranges of the datasets between the two studies. This same trend mimics the ICV values reported for Asian children by Kamochi et al.43 which are also reported as higher than average and reflect the influence of ethnicity on skull size and shape. This underscores the importance of using population-focused craniometric references when evaluating craniosynostosis and in clinical decision-making.

Bone perimeter analysis and bone growth

The average perimeter of the parietal and frontal bones expanded approximately 10 cm in the first 7 months of life, varying from 16.4 cm to 25.8 cm and 25.0 cm to 37.4 cm, respectively. Notably, the occipital bone increased by approximately 20 cm in the same time period (ranging from 17.9 cm to 36.9 cm) and then remained relatively stable until 8 years of age (37.3 cm). The mean growth rate of the occipital bone in the first 7 months was 4.8 cm/month, compared to the slower rates of 3.6 cm/month for the parietal bones and 2.4 cm/month for the frontal bones. (Fig. 8b). This reveals a non-linear pattern of skull growth due to non-synchronous growth spurts of individual bones.

The perimeter of the parietal bones underwent a minor increase from 8 to 15 months (36.8 cm to 37.9 cm) and stopped expanding by 36 months when it reached approximately 40 cm. Conversely, the perimeter of the frontal bones increased between 12 months to 8 years, which is possibly related to the development of the frontal lobe and facial structures during this time period. The temporal bone is the smallest bone of the cranial vault. Despite its similar variation to that of the other bones, growth of the temporal bone was constant and reached approximately 20 cm at 8 years of age.

Early brain development is intricate and complex, and this study provides crucial insight into this process by correlating non-linear patterns of bone development with understanding how the brain develops concurrently. The increased growth of the occipital bone from 0 to 7 months suggests that the underlying structures, the cerebellum and occipital lobe—which are associated with functions such as balance, movement, and visual processing—develop first and most rapidly in the first months of life compared to other regions of the brain44. When the occipital bones enter a slower growth phase after 7 months, there is a period of increased growth in the parietal bones; this suggests the underlying parietal lobe—which is linked to functions such as spatial awareness, perception, and attention—is also undergoing a period of growth during this time45,46,47,48.

To date, there are no reports in the literature that demonstrate the dynamic development of individual pediatric skull bones, how their growth patterns relate to age, and skull size. Our data points to an allometric drive for the growth of individual bones. The strong Pearson correlation coefficient values presented in Fig. 7 and the statistically significant p values of the subsequent Student’s t-test (frontal bone p = 3.3 × 10−6, parietal bone p = 3.8 × 10−9, temporal bone p = 0.002, occipital bone p = 0.0001) suggest that the relationship between cranial bone perimeter and age is powerful. The untransformed age and bone perimeter data for each of the cranial bones are shown in Fig. 8. The power growth profile of the cranial bones suggested that bone growth is highest immediately postpartum and slows as the infant ages. Skull bones grow to accommodate the developing brain and this power growth profile may correspond to a surge in brain development to process the overwhelming amount of sensory information the infant is introduced to immediately ex utero49,50.

Correlation of cranial dimension with cranial volume

Cranial indices are used clinically to assess the size of the skull and to determine critical landmarks for neurosurgical interventions. The cranial indices we used in this analysis were the Towering Index (TI) proposed by Pindrik et al. as a measure of vertical elongation and the Cephalic Index (CI) as a measure of cephalic elongation, which was clinically validated as a normative value by van Lindert et al.51. Our analysis of the effect of age, TI, CI, and the interactions between these three variables on ICV indicates that age was the only variable that significantly influenced cranial volume (Table 2). This finding supports the description by Liang et al.19 where size variation is due to skull growth, rather than shape predominating over the first two years of life.

If the volume of the skull increases over time, we can assume the dimensions of the skull in the three cardinal directions must also change. This assumption led us to investigate why our analysis of the effect of TI and CI on ICV do not describe the geometric changes we would expect for an increase in cranial volume. We examined the influence of age, glabella-opisthocranion diameter (GOPD), biparietal diameter (BIPD), and the distance from the external auditory meatus to the vertex (EAV) on cranial volume as these measurements are only associated with a single cardinal direction. Table 2 provides the results of our ANOVA on these three dimensions, which shows that age, BIPD, and GOPD all influence cranial volume, while EAV does not. This suggests that the growth of the cranium in the anterior-posterior and latero-lateral directions may have a more substantial correlation with cranial volume than growth in the inferior-superior dimension.

After identifying that age, frontal bone perimeter, and parietal bone perimeter had a significant effect on cranial volume, we sought to determine whether there was any interaction between these variables that our initial analysis may have missed, so we conducted a subsequent ANOVA. This analysis indicated there was no interaction between these three parameters (Table 2).

Closure of sutures and fontanelles

At birth, all cranial sutures are open. By 1 month, the metopic suture starts to close from the nasion to the anterior fontanelle and is entirely fused by 7 to 8 months. The sphenofrontal suture begins to close at 2 months and is partially closed by 12 months. The squamous suture begins closing at 1 month at its posterior junction with the parietal bone, fuses at its anterior junction with the parietal bone at 2 months, and is partially fused at 6 to 8 months. The coronal suture starts to close in the pterion laterally to medially at 3 months, is partially fused by 2 to 4 years, and is incompletely closed by 6 to 8 years (supplemental Fig. S3, S4, S5).

We investigated whether the non-linear growth pattern of individual skull bones described in the previous section is a predictor for the sequence and directionality of suture closure. The pattern of suture closure and directionality can be visualized in the first months of life from lateral to medial and posterior to anterior (supplemental Fig. S3, S4, S5). The sagittal suture begins to close at the articulation with the occipital bone at 3 to 4 months, progresses posterior to anterior, and completes partial fusion by 6 to 8 years. The lambdoid suture also starts to fuse at the junction with the sagittal suture at 3 to 4 months, progresses from medial to lateral, and is partially fused by 6 to 8 years.

Our study’s results reproduce the suture closure patterns and variations described in the literature11,17,19,41,52. According to Weinzweig et al.27, metopic suture fusion in normal, nonsynostotic children is complete by 6 to 8 months (n = 76). Another study by Pindrik et al.40 reported the frequency of metopic suture closure in 324 subjects between 0 and 24 months of age, with closure rates of 38.5% at 3 months, 69.2% at 6 months, and 100% at 9 months. Ruengdit et al.12 summarize the use of cranial suture closure as an indicator of age in adults; it has been reported that all sutures begin to close at 22 to 26 years of age and complete fusion occurs by the late 30s and early 40s, with the exception of the metopic suture which closes earlier. In our study, none of the cranial vault sutures were closed by 8 years except for the metopic suture, which agrees with the literature, and reflects our current understanding of ongoing development of the brain into adulthood.

Visualization of anterior fontanelle (AF) and posterior fontanelle (PF) closure is shown in supplemental Fig. S3, S4, S5. The AF remains open for the first 12 months and starts to close progressively at 7 to 8 months until it is entirely fused by 18 months to 4 years. The PF can be completely obliterated in 7 to 18 months. The sphenoidal fontanelle is visible for up to 3 months, while the mastoidal fontanelle can be observed until 8 months, after which it fuses completely.

The timings of fontanelle fusion are described in the literature. Pindrik et al. analyzed AF fusion in 495 head CT scans of North American children aged 0 to 24 months. They observed that anterior fontanelle closure (AFC) steadily increased from 9 months (5% closed) to 20 months (88% closed), then remained between 88% and 90% closed from 20 to 24 months; this aligns with the results of the present study. Conversely, Kirkpatrick et al.24 reported that the AFC rate in children from New Zealand reached 25% closed at 4 to 6 months and increased to 80% closed by 13 to 18 months. The AFC of Maori children may have initiated at an earlier stage than those evaluated by Pindrik et al. or in the present study (4 to 6 months compared to 7 to 9 months). Additionally, Kirkpatrick et al. reported that the PF closes at 3 months, while the present study shows that the PF starts closing at 3 months and is closed by 18 months, although the sutures may remain unfused for up to 8 years.

Cranial bone perimeter correlation with cranial volume and suture closure

Table 2 shows the ANOVA results for the effect of cranial bone perimeter on cranial volume. Our analysis indicates that age and the perimeter of the frontal and parietal bones had a significant effect on cranial volume (P = 3.77e-06 and P = 0.0013 respectively). Additionally, the anterior-posterior (GOPD) and latero-lateral (BIPD) dimensions both had a significant effect on cranial volume (P = 0,00101 and P = 2.10e-08, respectively). while the perimeters of the temporal and occipital bones did not (P = 0.4743 and P = 0.4661 respectively). If we convert these cardinal directions into anatomical planes, we can see that bone growth within the coronal plane and sagittal plane contributes most to increasing cranial volume. This finding suggests that growth of the frontal and parietal bones have a stronger correlation with increasing cranial volume, which agrees with the literature available. (Table 2)

Directionality of suture and fontanelle closure

When we put the data describing suture and fontanelle closure in context with the growth patterns of the skull bones, we can predict the directionality of suture closure. Posterior fontanelle closure (PFC) is mostly driven by growth of the occipital bone (r=-0.32, p < 0.05) and, to a lesser degree, the growth of the parietal bone (r=-0.24, p < 0.05). This demonstrates that PFC occurs from posterior to anterior due to the major contribution of occipital bone growth in the first 8 months of life (Fig. 7b). Conversely, AFC is primarily driven by the growth of the frontal bone (r=-0.45, p < 0.05) and, to a lesser extent, the growth of the parietal bone (r=-0.28, p < 0.05), which demonstrates that AFC occurs from anterior to posterior due to the predominant contribution of the frontal bones compared to the parietal bones. Additionally, AFC is initiated after PFC, and occurs around 4 months of life. (Fig. 7) This pattern of sutures and fontanelles directionality closure was also described by Li et al.17 in children up to 3 years. Moreover, our study aligns with the literature which proposes that brain development advances rapidly throughout early childhood in a carefully choreographed posterior-to-anterior arc45,46,47,48,49,50,53,54. Our results provide evidence of the same pattern of direction for both suture closure and brain development, suggesting that these two processes are correlated.

Conclusion

As infants age, the cranial volume must increase to accommodate the developing brain. We have shown that individual bones exhibit their own non-linear growth patterns. The occipital bone undergoes its main growth spurt from 0 to 8 months, followed by growth of the frontal and parietal bones. This differential bone growth is responsible for the directionality of suture and fontanelle closure occurring from posterior to anterior in the first 8 months in coordination with occipital bone growth, and subsequently from anterior to posterior after 8 months following the growth of the frontal bone. We validated the used of clinical indices (i.e., TI and CI) despite these differential growth patterns. Our visualization data also provides the first comprehensive 3D visual references for skull development during the first 8 years of life which will be an invaluable resource for clinical decision making in pediatric neurosurgery.

Limitations and future directions

Despite many high-resolution 3D CT scan reconstructions being evaluated for this study and the results of our analysis being consistent with typical observations in the clinical context, this cohort had a small sample size for the age groups during the first year. We acknowledge the potential sample bias in this data since the subjects were not equally distributed across age groups and recommend incorporating more subjects within each age group and analyzing variation between sexes and ethnicities to improve the generalizability of the study sample to the pediatric population. Furthermore, review of CT scans by more than one researcher, with a defined method to correct for any appreciable inter-observer error, could improve the quality of the data analysis.

Data availability

Materials described in this manuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any researcher wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Standring, S. et al. A. C. and C. W. Grays’s Anatomy - The Anantomical Basis of Clinical Practice (London, UK, 2016).

Pfefferbaum, A. et al. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study of changes in brain morphology from infancy to late adulthood. Arch. Neurol. 51, 874–887 (1994).

Richtsmeier, J. T. & Flaherty, K. Hand in glove: brain and skull in development and dysmorphogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 469–489 (2013).

Pitirri, M. K. et al. Come together over me: cells that form the dermatocranium and chondrocranium in mice. Anat. Rec. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.25295 (2023).

Baird, L. C. & Proctor, M. R. Craniosynostosis. in Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery (eds Allbright, L., Pollack, I. & Adelson, P.) 237–248 (Thieme, New York, 2015).

Flaherty, K., Singh, N. & Richtsmeier, J. T. Understanding craniosynostosis as a growth disorder. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Dev. Biol. 5, 429–459 (2016).

Sgouros, S. et al. Skull Base Growth in Childhood. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 31 (5), 259–268 (1999).

Sivakumar, W. R., Riva-Cambrin, V. M. & Kestle, J. J. Pediatric Neurosurgery: Tricks of the Trade - Ventricular Shunting for Hydrocephalus (Thieme, 2016).

Juneja, P., Munjal, A. & Hubbard, J. B. Joints Anatomy. StatPearls (2024).

Likus, W. et al. Cephalic Index in the First Three years of Life: study of children with normal Brain Development based on computed tomography. Sci. World J. 2014, 1–6 (2014).

Pindrik, J., Ye, X., Ji, B., Ahn, E. & Pendleton, C. Anterior Fontanelle Closure and size in full-term children based on Head Computed Tomography. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila). 53, 1149–1157 (2014).

Ruengdit, S., Case, D. T. & Mahakkanukrauh, P. Cranial suture closure as an age indicator: a review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.110111 (2019).

Fan, F. et al. Age estimation by multidetector computed tomography of cranial sutures in Chinese male adults. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 171, 550–558 (2020).

Opperman, L. A. Cranial sutures as Intramembranous Bone Growth sites. Dev. Dyn. 219, 472–485 (2000).

Reardon, W. Craniosynostosis. Diagnosis, evaluation and management. J. Med. Genet. 37, 727–727 (2000).

Cronin, B. J. et al. A comparison of intracranial volume growth in normal children and patients with Metopic Craniosynostosis. J. Craniofac. Surg. 31, 142–146 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. A statistical Skull geometry model for children 0–3 years old. PLoS One. 10, 1–13 (2015).

Libby, J. et al. Modelling human skull growth: a validated computational model. Interface. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0202 (2017).

Liang, C. et al. Normal human craniofacial growth and development from 0 to 4 years. Sci. Rep. 13, 9641 (2023).

O’ Sullivan, E. et al. The 3D skull 0–4 years: a validated, generative, statistical shape model. Bone Rep. 15, 101–154 (2021).

Giulia Rossini, D., Cavallini, C., Cassetta, M. & Barbato, E. 3D cephalometric analysis obtained from computed tomography. Review of the literature. Ann. Stomatol. (Roma). 2, 31–39 (2011).

Anderson, P. J., Yong, R., Surman, T. L., Rajion, Z. A. & Ranjitkar, S. Application of three-dimensional computed tomography in craniofacial clinical practice and research. Aust Dent. J. 59, 174–185 (2014).

Waitzman, A. A., Posnick, J. C., Armstrong, D. C. & Pron, G. E. Craniofacial skeletal measurements based on computed tomography: part II. Normal values and Growth trends. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 29, 118–128 (1992).

Kirkpatrick, J., Bowie, S. & Mirjalili, S. A. Closure of the anterior and posterior fontanelle in the New Zealand population: a computed tomography study. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14253 (2018).

Paetz, P., Goetz, G. F., Lanfermann, H. & Giesemann, A. M. The developing temporal bone: computed tomography measurements and assessment of suture closure from birth to 18 years of age. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 39, 663–671 (2017).

Nam, H., Han, N., Eom, M. J., Kook, M. & Kim, J. Cephalic Index of Korean Children with Normal Brain Development during the First 7 years of life based on computed tomography. Ann. Rehabil Med. 45, 141–149 (2021).

Weinzweig, J. et al. Metopic synostosis: defining the temporal sequence of normal suture fusion and differentiating it from synostosis on the basis of computed tomography images. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 112, 1211–1218 (2003).

Frassanito, P. et al. The growth of the neurocranium: literature review and implications in cranial repair. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 35, 1459–1465 (2019).

Greenberg, M. S. Handbook of Neurosurgery (Thieme, 2019).

Raabe, C., Fichtner, J., Beck, J., Gralla, J. & Raabe, A. Revisiting the rules for freehand ventriculostomy: a virtual reality analysis. J. Neurosurg. 128, 1250–1257 (2018).

Huyette, D. R. et al. Accuracy of the freehand pass technique for ventriculostomy catheter placement: retrospective assessment using computed tomography scans. J. Neurosurg. 108, 88–91 (2008).

Gusmão, S., Silveira, R. L. & Arantes, A. Pontos referenciais nos acessos cranianos. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 61, 305–308 (2003).

Reis, B. L., Silveira, R. L., Da & Gusmão, S. N. S. Sphenopterional Point: Strategic Point for Burr Role Placement in Frontotemporal Craniotomies. World Neurosurg. 105, 399–405 (2017).

Reis, C. V. C. et al. The Anterolateral Limit of the Occipital lobe: an anatomical and imaging study. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base. 77, 491–498 (2016).

Kikinis, R., Pieper, S. D. & Vosburgh, K. G. 3D slicer: a platform for subject-specific image analysis, visualization, and clinical support. Intraoperative Imaging Image-Guided Therapy. 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7657-3_19 (2014).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

Larobina, M. & Murino, L. Med. Image File Formats. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-013-9657-9

Harkey, T., Baker, D., Hagen, J., Scott, H. & Palys, V. Practical methods for segmentation and calculation of brain volume and intracranial volume: a guide and comparison. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 12, 3748761–3743761 (2022).

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: growth velocity based on weight, length and head circumference: methods and development. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44026 (2009).

Pindrik, J., Molenda, J., Uribe-Cardenas, R., Dorafshar, A. & Ahn, E. Normative ranges of anthropometric cranial indices and metopic suture closure during infancy. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 18, 667–673 (2016).

Cohen, M. M., (Meyer, M. & Pruzansky, S. Craniosynostosis: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management (Raven Press, 1986).

Cole & Richtsmeier, J. T. A simple method for visualization of influential landmarks when using Euclidean Distance Matrix Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 107, 273–283 (1998).

Kamochi, H. et al. Growth curves for intracranial volume in normal Asian children fortify management of craniosynostosis *. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 45, 1842–1845 (2017).

Barbeito-Andrés, J. et al. Modeling the effect of brain growth on cranial bones using finite-element analysis and geometric morphometrics. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 42, 741–748 (2020).

Lebel, C. & Deoni, S. The development of brain white matter microstructure. NeuroImage vol. 182 207–218 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.097 (2018).

Andre, Q. R., Geeraert, B. L. & Lebel, C. Brain structure and internalizing and externalizing behavior in typically developing children and adolescents. Brain Struct. Funct. 225, 1369–1378 (1973).

Reynolds, J. E., Grohs, M. N., Dewey, D. & Lebel, C. Global and regional white matter development in early childhood. Neuroimage. 196, 49–58 (2019).

Benischek, A. et al. Pre-reading language abilities and the brain’s functional reading network in young children. Neuroimage. 217, 116903 (2020).

Moura, L. M. et al. Coordinated brain development: exploring the synchrony between changes in grey and white matter during childhood maturation. Brain Imaging Behav. 11, 808–817 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Brain anatomical networks in early human brain development. Neuroimage. 54, 1862–1871 (2011).

Van Lindert, E. J. et al. Validation of cephalic index measurements in scaphocephaly. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 29, 1007–1014 (2013).

Mercan, E., Hopper, R. A., Maga, A. M. & Murat Maga, A. Cranial growth in isolated sagittal craniosynostosis compared with normal growth in the first 6 months of age. J. Anat. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13085 (2019).

Deoni, S. C. L. et al. Development/Plasticity/Repair Mapping Infant Brain myelination with magnetic resonance imaging. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2106-10.2011 (2011).

Bethlehem, R. A. I., Seidlitz, J. & White, S. R. et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature. 604, 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04554-y (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the UBC Hackspace for Innovation and Visualization in Education (HIVE) for their technical assistance with the models’ creations and constructive feedback on the current work, especially Monika Fejtek for creating and formatting all the figures and tables. We would also like to thank Qian Zhang, a biostatistical analyst at the BCCH Research Institute, for her support with the statistical analysis of the ICVs. The authors are extremely grateful to the many researchers and students at Simon Fraser University’s (SFU) Functional & Anatomical Imaging & Shape Analysis Lab for their unwavering dedication. Special thanks to Dr. Mirza Faisal Beg, Lab Director, Dr. Karteek Popuri, Assistant Professor, and Dr. Da Ma, Assistant Professor, for providing constant assistance throughout the entire process. We also want to acknowledge the continuous support of the Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery and the BCCH team, especially the commitment of Alexander Cheong, Clinical Research Coordinator, who helped edit the protocol for this project and with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CGS – study concept, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. MHO - study concept, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. ANS – data analysis, manuscript writing. MST - data analysis, manuscript writing. RGH - study concept, data collection, data analysis, Fig. 5, manuscript writing. ID – 3 D models designer (Fig. 6), manuscript review. BL - substantively revised the reviewed manuscript. CK - study concept, data analysis, manuscript writing. PS - study concept, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schaurich, C.G., Saraco, A.N., Oruganti, M.H. et al. Allometry of human calvaria bones during development from birth to 8 years of age shows a nonlinear growth pattern. Sci Rep 14, 26205 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77315-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77315-8