Abstract

Heat-resistant fungal conidia are a common source of contamination and can cause significant difficulties in producing spawns. Through the use of PCR method, Aspergillus tubingensis and Aspergillus flavus as common microbial contaminants found in wheat grain spawn were identified that had been sterilized at 120 ºc for 2 h. Since these conidia are highly resistant to standard sterilization techniques, alternative methods were used to treat them with NaOCl and cold plasma and evaluate their effectiveness in reducing contamination. Optical emission spectroscopy (OES) analysis of the plasma showed dominant emissions from the N2 second positive system and N2+ first negative system, while reactive oxygen species (ROS) spectral lines were undetected due to collision-induced quenching effects. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDXS) analyses revealed notable alterations in the elemental makeup of conidia surfaces, as evidenced by a marked rise in levels of Na, O, Cl (in the case of NaOCl treatment) and N (in the case of plasma treatment). The conidia size was reduced at lower levels of NaOCl, but with increased concentrations and plasma treatment, the conidia underwent rupture and, in some cases, pulverization. The research suggests that utilizing a combined approach can be highly effective in eliminating heat-resistant fungal conidia and drastically cutting down the sterilization time for producing wheat spawn to only 30 s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Grain spawn is widely employed to support the growth of mycelium facilitating exponential expansion. Various substrates can be used to create grain spawns, including brown and white rice, wheat, millet, and rye. Among these substrates, wheat is the most commonly used grain for mushroom cultivation. Mushroom mycelium begins to grow in organic substrates like wheat as a solid state medium under optimal chemical and physical conditions1,2. Fungal conidia are a challenging issue encountered in the spawn-production process. The low thermal conductivity of the wheat substrate, along with the protective effects of nutrients in the exploded grain kernels, can make substrate contamination difficult to overcome2. This is due to the conidia’s resistance to steam sterilization, which is typically carried out at 121°C for 2.5 hours. Thermo-resistant conidia can survive this process and lead to incomplete sterilization, which is a frequent cause of spawn contamination. To reduce conidia resistance, various methods are used, including thermal and non-thermal processes3,4. Thermal methods such as pasteurization and sterilization, as well as non-thermal methods such as ultrasound, cold plasma, UV radiation, chemical sterilization, and high hydrostatic pressure, offer the potential to disinfect or sterilize media5. Recent studies have indicated that cold plasma has been reported to be an effective sterilizing approach for a wide range of microorganisms on cereal surfaces and in complex media6,7. Cold plasma is effective in killing a wide range of fungi, including Candida albicans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, and Fusariumspp8,9,10.. Among the various fungi studied, Aspergillus has demonstrated low susceptibility to cold plasma inactivation due to its high potential for conidia production11. Chemical sanitizers are among the most commonly used disinfectants and have been extensively employed for sterilization purposes. Sodium hypochlorite, among various chemical agents, has been widely utilized as a microbial termination agent (Finten et al., 2017). Upon dilution of sodium hypochlorite in water, it acts as a strong chlorine solution with oxidizing properties that demonstrate a lethal effect on various types of microorganisms. McNeil et al. (2015) linked oxidation agents with fungal conidia eradication. However, there are concerns over the possible production of chlorinated carcinogenic compounds at high concentrations of strong oxidizing agents. Recently, research has focused on the potential synergistic effects of combined disinfection methods12,13,14. Investigators have recently demonstrated a significant synergistic effect of combined chemical sterilization and cold plasma treatment on food-borne pathogens15,16. There are no reports on the synergy effects of sodium hypochlorite and cold plasma on naturally occurring conidia contamination in wheat grain spawn. The objective of this research was to isolate fungal conidia contaminating the grain spawn, to identify the isolated species using PCR. Due to the inherent resistance of the conidia to plasma, a two-step approach is employed. Initially, the samples are exposed to sodium hypochlorite, which serves to weaken the conidia’ resistance. Subsequently, cold plasma is utilized to effectively eliminate the weakened conidia.

Results and discussions

Fungi isolation and identification

A comparison of the obtained sequences of the ITS region with the deposited ones at NCBI showed that isolate B1 was 100% similar to KP412254.1 (A. tubingensis) and 99.8% similar to MT268535.1 (A. niger). Also, the isolate B2 showed about 99.5% similarity with MK271279.1 (A. flavus) and MT680401.1 (A. oryzae). As shown in Fig. 1, the isolates B1 and B2 were grouped with the mentioned Aspergillus species. Therefore, the isolates B1 and B2 are deposited at NCBI as Aspergillus sp. with the accession numbers OL655411 and OL655412, respectively.

Furthermore, the calmodulin gene (CaM) sequence was applied for the accurate identification of the Aspergillus species. Results showed that isolate B1 was 99.4% similar to MH644917.1 and belonged to A. tubingensis with the isolate B2 99.6% similar to MN986405.1 and belonged to A. flavus. As shown in Fig. 2., the isolates B1 and B2 were grouped with A. tubingensis and A. flavus, respectively. The CaM gene sequence of the isolates B1 and B2 are available with an accession number OR037291 at NCBI. Based on the sequences of the ITS region and calmodulin gene, the isolates B1 and B2 in this study belonged to A. tubingensis and A. flavus, respectively.

Optical emission spectroscopy of plasma

The optical emission spectrum of the SBD plasma is shown in Fig. (3). Figure (3) shows most of the peaks belong to the N2 second positive system (C3Π_ − B3Πg) emissions at 337.1, 353.8, 357.4, 375.1, 380.4, and 399.2 nm and N2+ first negative system (B2Σ + u − X2Σ + g) at 391.2 nm (De Geyter, 2013; Wang et al., 2012). The spectrometer failed to detect ROS spectral lines (777 and 845 nm) because of collisions between N2 and O2 and excited O atoms. These collisions cause the quenching rate to dominate over the radiative rate, preventing the detection of these lines while these oxygen species are generated during the air plasma discharge (De Geyter, 2013; Walsh et al., 2010).

The effect of NaOCl treatments against A. Flavus and Tubingensis conidia germination

It was observed in the experiment that A. flavus conidia retained their resistant states after being treated with 10 PPM of NaOCl. A crucial factor in reducing conidia germination was lengthening the exposure time and raising the NaOCl concentration. At 50 and 100 PPM concentrations, NaOCl effectively controlled and eliminated A. flavus conidia for all exposure times except 3 h, which resulted in a reduction of conidia germination by 0.374 and 1.441 log, respectively after 4 days. The revival of conidia between 4 and 10 days after sterilization, depending on the applied sterilization conditions, is a common problem facing producers with edible and medicinal mushroom spawn. In the same vein, a number of colonies were observed in the media spayed with NaOCl-treated conidia with an incubation period of at least 10 days, while those conidia were unable to germinate under the 4 day-cultivation. For example, at the 50 PPM NaOCl, a 1.919 log reduction was observed after 6 and 9 h, as well as a 1.618 log reduction after 18 h of exposure time, while there were no signs of growth after 4 days. The populations of living conidia were reduced by 1.618 logs at concentrations of 100 PPM NaoCl for 6 h. The higher exposure time, 9 and 18 h, aggravated the conidia eradication with 1.618 and 1.919 logs reductions. The log reduction of conidia treated at concentrations of 1000 and 10,000 PPM for 3 h was 1.441 and 1.919 log, respectively after 10 days. Importantly, all treated conidia were unable to grow during the 4 days cultivation on PDA media. Overall, a 3 h exposure time was not effective in eradicating all treated conidia employing different concentrations (Table 1).

A. tubingensis at 75 × 105 colony forming unit CFU /ml were exposed to different concentrations of NaOCl. The results indicated that 10 PPM NaOCl gave no killing of A. tubingensis conidia. However, exposure to 10 PPM of NaOCl after 3, 6, 9, 18, and 24 hours reduced the germination rates of conidia by 0.061, 0.176, 0.193, 0.221, and 0.273 log respectively. The 50 and 100 PPM NaOCl- treatments provided lethal effects on conidia for all application times, except for 3 h which led to a 0.971 and 1.273 log reduction of germination activity (Table 1). The higher concentrations of NaOCl resulted to a strong sporicidal activity on the conidia of A. tubingensis. Reports such as that conducted by17,18,19have shown that NaOCl, as oxidizing compound, inhibited conidial germination. A number of studies have also found that Aspergillus species were susceptible to sodium hypochlorite20,21 demonstrated that a concentration of 250 PPM of sodium hypochlorite, combined with an exposure time of 8.5 min, was found to be the optimal condition for achieving a considerable log reduction of Aspergillus nomiusconidia. Similarly22, reported that most conidia of A. flavusare able to tolerate sodium hypochlorite concentrations up to 100 PPM without being completely killed. However, there is growing concern over the use of high concentrations of sodium hypochlorite for sterilization due to its potential toxicity to living organisms. NaOCl is a strong oxidizing agent that can cause skin and eye irritation, respiratory problems, and other health effects at high concentrations23. In addition, the use of high concentrations of NaOCl for sterilization can also lead to the formation of harmful byproducts such as chloramines and trihalomethanes24. To address these concerns, researchers are exploring alternative methods for sterilization that are less toxic and more environmentally friendly. For example, some studies have investigated the use of low-temperature plasma with disinfecting agents to enhance the safety of food components16,25.

Cold plasma treatment of conidia germination

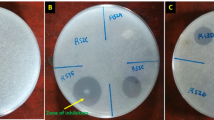

A. flavus at 83 × 105 CFU/mL were sprayed onto PDA culture medium and subjected to the different conditions of cold plasma power, 20 W (voltage 4.3 kV and frequency 7.4 kHz), 40 W (voltage 5.9 kV and frequency 7.4 kHz) and 60 W (voltage 7 kV and frequency 7.4 kHz) at ambient temperature for two minutes. The conidia sample that was treated with 20 W (voltage 4.3 kV) germinated after 3 days on PDA culture medium, while conidia were inactivated by 40 and 60 W. Therefore, a power of 40 W was selected for further studies.

A. flavus conidia at 83 × 105CFU/ml were incubated on PDA medium culture and exposed to the 40 W of cold plasma treatment (5.9 kV voltage) for 30 s, 1, 2, 5 and 10 min. The results showed that 0.3 and 0.4 log reductions in conidia activity were observed after 30 s and 1 min (after three days), while the 2, 5, and 10 min-cold plasma treated conidia were inactivated after 4 days. After 10 days, the conidia treated for 2 min germinated with only one colony observed, while the rest of the treated conidia lost the ability to germinate. Reports by26,27 showed that the generation of ROS and RNS were the main components by which cold plasma technology exerts its antimicrobial activity. A conidia suspension of A. tubingensis (75 × 105 CFU/ml) was cultivated on PDA culture medium and exposed to 40 W cold plasma treatment (5.9 kV voltage and 7.4 kHz frequency) for 2, 4, 6, and 8 min. The results show that the treated conidia did not germinate under any of the treatment times. Similarly, artificially inoculated seeds with conidia of phytopathogenic fungi, including A. flavus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus parasiticuswere disinfected by plasma treatment28,29,30,31 demonstrated that plasma at a power of 40 W for duration of 20 and 25 min was capable of inhibiting the growth of A. flavus on the PDA and brown rice cereal bars respectively. Plasma at a power of 60 W for 6 min was found to provide results than that of 40 W in the inactivation of A. flavus and A. parasiticus32. An exposure time of 240 s at 100 W was sufficient to inhibit 100% growth of A. flavusconidia using cold plasma33. A noteworthy finding was that in comparison to this research, previous studies have shown a greater power demand for the use of cold plasma in product disinfection10,34. One crucial aspect that deserves attention is the potential of nutritional components in food items to safeguard against conidia inactivation, an area that has been largely neglected in scientific investigations. In an effort to nullify the protective effects, the extracted conidia were placed on the PDA medium and treated with cold plasma, resulting in a decrease in both plasma power and treatment duration in this study. However, to further reduce the time and disinfection power of cold plasma, a combination of NaOCl and cold plasma was used.

Synergy of NaOCl and cold plasma on A. Flavus and A. tubingensis -conidia inactivation

The 50 PPM NaOCl- treated conidia with 6 h exposure time were exposed to the 40 W cold plasma treatment (5.9 kV voltage and 7.4 kHz frequency) for 30 s, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min. The results show that, even after 14 days, conidia germination was suppressed. This suggests that combining cold plasma with NaOCl treatment may be an effective method for inactivating fungi conidia while minimizing any induced damage to the food components along with reducing potential toxic residues. By combining plasma and NaOCl treatment, A. flavus conidia could be inactivated in 30 s. To test the effectiveness of this approach on A. tubingensisconidia, conidia were exposed to cold plasma for 10, 20, 30, and 60 s under the same conditions. The results indicated that the combined treatment of plasma and NaOCl had a synergistic effect that resulted in conidia inactivation. Plasma treatment alone can be effective in killing microbes, but it can be energy-intensive. By using chemical agents in combination with plasma, the energy required for plasma treatment can be reduced while still achieving high levels of microbial reduction. A similar result was obtained by35,36,37. Overall, these studies and the present research suggest that the combination of plasma and NaOCl can be an effective strategy for reducing microbial contamination.

Analysis of field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) was utilized to capture microstructure images of A. flavus and tubingensis conidia. Figure 4 shows that the size of the conidia varied from different angles, ranging from 4.38 to 3.77 μm for A. flavus and 3.877 to 3.737 μm for A. tubingensis. In the final analysis, two conidia were found to have circle shapes. The surfaces of both A. flavus and tubingensis presented delicately spiny conidia. Bundles of rodlets were observed on the surface of the conidia, resulting in a slightly roughened structure. Notably, a hole was observed at an angle where the conidia diameter was 3.77 μm on the surface of A. flavusconidia. Such a hole was seen by38 in Aspergillus nigerconidia39. reported that A. flavus conidia were 4 μm in diameter.

Figure 5 indicates that the size of the 50 PPM NaOCl-treated A. flavusconidia reduced from 4.77 μm to 3.88 μm at one angle, and from 3.88 μm to 3 μm at another angle. This view is supported by39 reported a reduction in the size of treated A. flavus conidia with an antifungal component. Specifically, the study found that the size of the conidia was reduced from 4.4 μm to 2.3 μm.

The chemical treatment used in the study resulted in a decrease in the size of the conidia and the destruction of the outer layer structure. Additionally, a deeper hole was observed on the conidia surface compared to the control. The use of 50 PPM NaOCl showed sporicidal activity against A. tubingensisconidia, and importantly, the chemical treatment caused some conidia to have a donut-shaped appearance, Moreover, such structures of conidia were aggregated. Recent evidence suggests that the blown-out cytoplasm of conidia is the main reason why the ruptured conidia aggregate40. As shown in Table 2, from the X-ray results, the surface of both A. flavus and tubingensis consisted of several elements, including C, O, Na, K, Cl, S, Ca, and P. The study found that carbon and oxygen were the most prevalent elements, making up 98.42% and 99.49% of the surfaces of A. flavus and tubingensis, respectively.

The percentages of carbon and oxygen on the surfaces of A. flavus and tubingensis are quite high, indicating that these elements are abundant in the conidia surfaces of these fungi, 88.39 and 88.52% respectively. In comparison to the control sample, the Na and Cl contents of A. flavus conidia have increased significantly after treatment with NaOCl. The increase in Na and Cl contents of A. tubingensisconidia is even more dramatic, with Na increasing from 0 in the control to nearly 7.574% in the treated conidia and Cl rising from 0.25% in the control to 3.75% in the 50 PPM NaOCl treated conidia. These changes in the elemental composition of the conidia surfaces may be due to the interaction of NaOCl with the cell wall of the conidia. However, the effect of chemical treatments, specifically NaOCl, on the composition of conidia surfaces has been largely neglected, despite its significance. NaOCl in water ionizes to Na + and the HOCl in acidic pH41. HOCl has an affinity to interact with sulfur-containing amino acids such as cystine and methionines42which were found to be composed of a main rodelt layer protein43. These interactions lead to the irreversible denaturation44 of rodlet proteins, and consequently the lethal effects observed on conidia germination.

Conidia treated with 104 PPM sodium hypochlorite

The research to date has tended to focus on log reductions of conidia germination rather than morphological and biochemical changes. The FESEM images reveal that there were significant surface changes to the treated A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia. In the case of A. flavus, the size of the conidia was significantly reduced compared to the control, and the aggregated conidia ranged in size between 574.7, 867, and 902.3 nm to 1.127 μm. This decrease in size suggests that the outer layer of the A. flavus conidia was significantly damaged or destroyed by the treatment with 104 PPM NaOCl. In contrast, the A. tubingensis conidia were completely ruptured, and submicrometer fragmented A. tubingensis conidia were released after exposure to a high concentration of NaOCl (Fig. 6). Moreover, what is not yet clear is the impact of NaOCl concentration on the pattern of conidia breakage.

As shown in Table 3, the results of the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis indicate that the surfaces of the treated A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia were mainly composed of carbon, oxygen, sodium, and chlorine. Oxygen was the most abundant element on the treated conidia surfaces, making up 83.05% and 55.12% of the A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia, respectively. A comparison of the results obtained from the control and treated conidia indicates that the treatment with NaOCl caused a dramatic increase in the oxygen content of the conidia surface. The oxygen content of A. flavus conidia increased from about 17% in the control sample to nearly 83% in the treated conidia, while the oxygen content of A. tubingensis conidia increased from 20% in the control sample to around 55% in the 104PPM sodium hypochlorite treated conidia. Sulfonic acid (R-SO3H), which suppresses protein formation and triggers protein degradation, is formed with excess HOCl45,46. The sharp rise in the oxygen content of the conidia surface may be attributed to the present this component on the surface of the treated conidia. In contrast, the carbon content on the conidia surface decreased significantly after treatment with NaOCl. The carbon content of A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia reduced from around 80% in the control sample to 7.19% and 28.05%, respectively, in the 104 PPM sodium hypochlorite treated conidia. This reduction in carbon content suggests that the treatment with NaOCl caused significant damage to the carbon-containing biomolecules on the conidia surface.

Regarding the Na and Cl content, the treatment with 10 4 PPM NaOCl caused a continual rise in the Cl content of A. flavus conidia from 0.26% in the control sample to 8.72% in the treated conidia in A. flavus. Similarly, the Na content of A. tubingensis conidia rose dramatically from 0% in the control sample to 12.86% in the treated conidia surface. These changes in Na and Cl content indicate that the treatment with NaOCl had a significant impact on the ionic composition of the conidia surface.

This view is supported by47 who writes that electrostatic forces imposed by the accumulation of charged particles such as Cl and Na cause the cell wall to rupture.

A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia treated with cold plasma

The effects of 40 W of cold plasma treatment, on the conidia of A. flavus and A. tubingensis were investigated with an exposure time of 10 min. Very few studies have investigated the impact of plasma on conidia shapes. FESEM images revealed that all of the treated A. flavus conidia were ruptured and surrounded by considerable fragments, which varied in size from a dominant small size of approximately 90 nm to the largest size of 800 nm. In contrast, the A. tubingensis conidia were completely pulverized by the cold plasma treatment (Fig. 7). So far, however, there has been little discussion about the chemical and plasma treatments on the pattern of conidia breakages. Significant fragments of ruptured A. flavusconidia with various sizes were observed when conidia were exposed to cold plasma, a pattern of rupture that was completely different from NaOCl-treated conidia. The mechanism underlying the destructive effect of cold plasma on the conidia involves the generation of ROS, RNS and free radicals within the plasma. These highly reactive species can interact with the cell wall, causing oxidation and disruption of the cell wall structure48. The destructive effect of cold plasma on the cell wall and the resulting cell leakage have been studied extensively31,49,50. In 2019, Sen et al. demonstrated that plasma has a destructive effect on conidia integrity, causing deformation on its surfaces, compared to the untreated conidial51. Similar findings suggest that cold plasma can effectively damage and break the conidiophores and vesicles of certain fungi species31. A detailed study of cold plasma on conidia by52 showed the conidia of Colletotrichum alienum were deformed by cold plasma treatment. Similarly, the A. flavusconidia treated with cold plasma were deformed and as a result depressions, holes, and protrusions were observed. In severe conditions, such structures were totally ruptured and disintegrated40,51,53. A study by54 reported that A. flavus conidia contamination on the surface of pistachio was completely removed after 18 min of plasma exposure.

As shown in Table 4, from the EDX results, it was found that both A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia showed a significant increase in oxygen content on their surfaces. The oxygen content of A. flavus conidia in the treated sample rose sharply from 17.7% (in the control sample) to 75%. Similarly, the oxygen content in A. tubingensis conidia in the treated sample increased from 20.2% (in the control sample) to 65.7%.

Interestingly, nitrogen was not detected on the control and NaOCl treated conidia surfaces, but was found to make up nearly 9% and 18.31% of the A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia, respectively. It was found that both A. flavus and A. tubingensisconidia showed an increase in oxygen content on their surfaces following plasma treatment. These observations suggest that plasma treatment generates ROS (reactive oxygen species) and RNS (reactive nitrogen species), which are reported for their anti-microbial impacts55, strongly binding to the surfaces of the conidia resulting in their destruction and increasing the oxygen and nitrogen content. The most striking result to emerge from the data is that one of the most important factors in the destruction of conidia can be the significant effect of plasma in changing the surface composition of conidia, which ultimately leads to the breaking of this structure.

Synergy effect of NaOCl and cold plasma on A. Flavus and A. tubingensis-conidia inactivation

Several studies have evaluated the synergistic effect of cold plasma and various disinfecting agents. Cold plasma has been shown to increase the effectiveness of disinfecting agents by improving their penetration and enhancing their antimicrobial activity25,56. However, far too little attention has been paid to weakening the conidia with lower concentrations of chemical disinfectants and then eradicating them all with cold plasma. To reduce the power and time treatment of cold plasma, 50 PPM-NaOCl-treated conidia were used to expose to 40 W of cold plasma for 2 min. Observations of the treated conidia under FESEM revealed a ruptured structure, indicating the efficacy of the combination of NaOCl and plasma in eradicating the conidia. Interestingly, the debris observed in the two exploded conidia were rough and irregular in shape, which differed from the debris observed in the A. flavus conidia treated with cold plasma alone (Fig. 8). These findings suggest that the combination of NaOCl and cold plasma treatment may have a synergistic effect in the eradication of conidia and that the resulting debris may have unique characteristics compared to those produced by cold plasma treatment alone. Comparably57, reported that amazonian fungal spores were ruptured with submicrometer size fragments released after exposure to high humidity and solar radiation.

As shown in Table 5, the EDX results show that the surface of the treated A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia consist mainly of carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and sodium (Na). Oxygen was found to be the most abundant element on the surfaces of both A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia, making up 48.24% and 50.19% of the surface composition, respectively. Comparison of the present results with those obtained from plasma-treated conidia alone revealed a dramatic increase in the Na content in the combination of chemical disinfectant and plasma-treated conidia. The Na content in the plasma-treated A. flavus conidia increased from almost zero to nearly 17% after combination treatment. Similarly, the Na content in the plasma-treated A. tubingensis conidia increased from 9.25% to around 22.56% after combination treatment. What is interesting in this data is that such an increase in Na content even after cold plasma, which is due to the negative effect of NaOCl, indicates a stable binding of sodium to the conidia surface. The comparison between the combination-treated A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia and those treated with plasma alone revealed a substantial decrease in the O content on the conidia surfaces. Specifically, the O content decreased from approximately 75% and 65% in the plasma treatment to 48.24% and 50.19% in the combination treatment, respectively. These results indicates that the oxygen binding on the conidia surfaces, which may have been formed as a result of NaOCl treatment, is relatively weak and can be effectively removed by the force exerted by the plasma treatment. Nitrogen detected in the plasma-treated conidia surfaces was found to make up nearly 10.27% and 13.78% of the A. flavus and A. tubingensis conidia, respectively in the combination-treated conidia.

Conidia remained viable throughout incubation at 50 PPM NaOCl concentration for 6 h after 10 days. On the other hand, the outer layer of the conidia structure exhibited a weakened state after being exposed to a 50 PPM NaOCl concentration for duration of 6 h. This prolonged exposure appears to have caused a reduction in the structural integrity of the outer layer, making it more susceptible to subsequent treatments, such as those applied during plasma treatment. RNS produced by plasma treatment reacted with the conidia, resulting in a considerable increase in the nitrogen content of ruptured conidia. In the plasma-NaOCl treatment, the reaction between nitrogen and sodium with the conidia appears to be stronger than the reactive oxygen. This is evident from the observation that the oxygen content of conidia surface reduced more significantly in the plasma-NaOCl treatment compared to the plasma treatment alone.

Fluorescence analysis of untreated, NaOCl and cold plasma-treated conidia

The conidial suspensions were stained with Nile Red and DAPI fluorescent dyes. Nile Red and DAPI are a lipid-soluble and nucleic acid dye respectively58,59. The resistant cell walls of A. flavus and A. tubingensis were found to impede the staining by Nile Red and DAPI fluorescent dyes differing from all the treated conidia (Figs. 9 and 10). Plasma attacks the outer layer of the conidia through the synergistic effects of various factors such as UV radiation and reactive species leading to rupture60,61. Consequently, such changes in the resistant structure of the conidia enhance the staining of all treated conidia. Prigione and Marchisio in 2004 showed that sodium hypochlorite and microwave irradiation was enhanced the staining of Aspergillus conidia, compared with untreated conidia62.

Incubation of A. flavus on sterilized wheat

Most studies have focused only on the adverse effect of cold plasma, alone or combined with another methods, on the control of microbial contamination in food products63,64. What is not yet clear is the adverse impact of cold plasma on conidia contamination without the protective effect of nutritional components. Since A. flavus exhibited more resilience than A. tubingensis, 1 ml of A. flavus conidia, which contained 83 × 105 CFU/mL was sprayed onto sterilized wheat and treated with 50 PPM of NaOCl for 6 h and subjected to the cold plasma power at 40 watts (voltage 5.9 kV and frequency 7.4 kHz) at ambient temperature for 30 s. In the process of producing wheat grain spawn on an industrial scale, it is worth noting that the wheat is subjected to a 24-hour soak in lukewarm water before sterilization. By utilizing 50 PPM, this soaking time was reduced to just 6 h. The A. flavus conidia inoculated to the sterilized wheat grew on the untreated wheat after 3 days on PDA culture medium, while there was no sign of growth on the plasma-treated wheat at 40 watts for 30 s (Fig. 11).

Several attempts have been made to eradicate the artificial incubated conidia on cereals by plasma treatment40,48,65. An important finding of this research is the reduction of the time and power of plasma treatment to achieve complete elimination of the conidia contaminations.

Conclusion

A significant challenge for edible and medicinal mushroom spawn production is contamination caused by heat-resistant conidia. The results of this research show that a high concentration of NaOCl with a long exposure time is needed, and similarly cold plasma requires a high energy dose with extended exposure. The use of NaOCl at low concentrations can damage the outer layer of conidia and cause cell shrinkage. Importantly, conidia growth was inhibited by breaking the spore structure. The surface elements of conidia changed significantly with the applied disinfection method, which could be the result of the interaction of active compounds produced by plasma and NaOCl, which changed the structure of the conidia wall leading permanent damage. The combined disinfection process of plasma and NaOCl can reduce the sterilization time of wheat artificially infected with A. flavus to 30 s and offers a promising method for disinfection, which meets the specific requires of producers for high-quality spawn.

Materials and methods

Sampling, fungal isolation, and identification

Sampling was carried out from wheat grain spawn and transferred to the Plant Protection Laboratory at the Faculty of Agriculture, Shahrood University of Technology, Iran. Samples were cultured on potato-dextrose-agar (PDA, QUELAB England) media and kept at 25 ± 2 °C for 5 days40. Total DNA was extracted from the purified isolates according to the method of SAFAEI et al. (2005)66. The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were examined on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), respectively. The ITS 1 (TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG)/ ITS 4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) primers were used to amplify the region of ITS1-5.8 S-ITS2 rDNA67. Thermal cycling for PCR involved: an initial denaturation for 3 min at 94 °C, then 35 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 57 °C for 30 s., and extension at 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. Also, to accurately identify the fungal species, the calmodulin gene (CaM) was amplified using CMD5 (CCGAGTACAAGGARGCCTTC) and CMD6 (CCGATRGAG GTCATRACGTGG) primers68 with the same thermal cycle mentioned above.

PCR products were visualized in a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel under UV light. The single band of approximately 700 bp was amplified and directly sequenced by the Bio Magic Gene company (www.bmgtechno.com). The obtained sequences were analyzed using Chromas Lite version 2.1 and Blast searched (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) against the GenBank nucleotide database.

The newly obtained sequences were aligned with the other sequences of the related species using MEGA X software. Finally, the phylogenetic tree was drawn using Maximum Parsimony (MP) clustering method by MEGA X software. 1000 bootstrap replicates were performed.

A. flavus and A. tubingensis cultivation and conidia extraction

The isolated and identified fungi were inoculated on PDA and grown at 25 °C for 5 days. Conidia were collected from heavily sporulating cultures of the A. flavus and A. tubingensis mycelium using a sterilized loop and suspended in distilled sterile water with 0.1% Tween 80 as a surfactant. The conidia were initially counted using a Neubauer chamber, and the suspension was diluted to obtain a final concentration of 106 conidia s/mL. To verify the number of viable conidia per mL, the conidia solution was further diluted and cultivated on PDA to count the viable conidia in the solution. The results showed that 83 × 105 CFU/mL of A. flavus and 75 × 105 CFU/mL of A. tubingensiswere present in the conidia suspension which were used for further studies48.

Investigating the effect of sodium hypochlorite on conidia inactivation

The experimental step described evaluates the antifungal properties of different concentrations of NaOCl against conidia germination of two Aspergillus species, A. flavus, and A. tubingensis. Conidia were collected from heavily sporulating cultures of the A. flavus mycelium grown on PDA medium at 25 °C for 5 days. A sterilized loop was then used to collect the conidia and suspended them in a 0.1% Tween 80 solution. The conidia were then treated with varying concentrations of NaOCl (10, 50, 100, 1000, and 10000 PPM) for different durations (3, 6, 9, 18, and 24 h). To assess the loss of cell culturability (i.e., germination) of the treated conidia, they were cultured on a PDA medium.

Plasma system

Surface barrier discharge (SBD) plasma was used to treat fungal contaminations which is discussed in detail in Ebrahimi et al. (2023). Briefly, the system contained a high-voltage power supply powering an aluminum disk (5 cm in diameter) electrode, along with a ground electrode which was a stainless steel mesh. The frequency of the power supply was set to7.4 kHz and the applied peak-to-peak voltages were 4.3, 5.9, 7 kV. The powered electrode was placed on the outer side of the lid of the petri dish and the ground electrode was fitted on the inside surface of the lid. By applying the voltage, SBD plasma was formed around mesh wires from atmospheric air inside the petri dish. The A. flavus samples were treated at 30 s, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min, and A. tubingensis samples were treated at 2, 4, 6, and 8 min. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Investigating the effect of cold plasma on conidia inactivation

Conidia of A. flavus and A. tubingensis that were extracted from the PDA medium were treated with air plasma at different power levels (20, 40, and 60 W) for different durations (30 s, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min). To effectively treat A. flavus and A. tubingensis, an optimal power level of 40 W was carefully chosen. The treatment duration for A. flavus was set at 30 s, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min, while for A. tubingensis, it was set at 2, 4, 6, and 8 min. This selection was based on the fact that A. flavus conidia exhibit greater resilience compared to A. tubingensis conidia. By varying the duration of treatment, the minimum exposure time required to effectively inhibit conidia germination was determined.

Investigating the synergic effects of sodium hypochlorite with cold plasma on conidia inactivation

The minimum concentration of sodium hypochlorite that exhibited fungistatic effects was identified and used in combination with cold plasma treatment to assess the effectiveness of this combined treatment in inhibiting conidia germination of A. flavus and A. tubingensis. Conidia of A. flavus and A. tubingensis were first treated with 50 PPM sodium hypochlorite for 6 h, which was the minimum concentration identified to exhibit fungistatic effects. The conidia were treated with sodium hypochlorite and subsequently exposed to cold plasma for varying lengths of time (30 s, 1, 2, 5, and 10 min for A. flavus; and 10, 20, 30, and 60 min for A. tubingensis, which exhibited lower resistance). By combining sodium hypochlorite treatment with cold plasma treatment, it can be determined if the two treatments have a synergistic effect in inhibiting conidia germination.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) analysis

In this experiment, the surface changes of the conidia of A. flavus and A. tubingensisdue to the treatments with NaOCl and cold plasma were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). To prepare the samples for observation, 10 µl of conidia were placed in aluminum foil and dried. The dried samples were then coated with a thin layer of gold (1.5–3 nm) using DSR1-Nano-structured coatings to make them conductive. The surface changes of the conidia, treated with NaOCl and cold plasma were then observed using a Sigma 300 HV, Zeiss, Jena, Germany field emission scanning electron microscope. FESEM is a type of electron microscopy that is capable of producing high-resolution images of the surface of materials51. In addition to observing the surface changes of the conidia, the identity and ratio of the elemental composition of the conidia surfaces were determined using an Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDXS). By analyzing the surface changes and elemental composition of the conidia surfaces, a better understanding of the mechanisms by which NaOCl and cold plasma treatments inhibit conidia germination was achieved.

Fluorescence analysis

To perform staining, fluorescent dyes DAPI and Nile Red were utilized with their concentrations in stock solutions adjusted to 0.2 and 1 mg, respectively62. 50 µl of dye was added to 50 µl of a conidia suspension, and then the mixture was incubated in the dark for 3 h69. A Leica DMI 6000 B epifluorescence microscope was used to capture images of the stained samples. Given the inherent resistance of fungal conidia to fluorescent dyes absorption, this treatment was carried out to ensure the success of the cold plasma and NaOCL used to kill conidia and increase dye absorption.

Statistical method

Each experiment was done three times, and The means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated with Microsoft Excel (2023). SPSS 16.0 was employed to compare the differences among means at a significance level of 0.05 using Duncan’s multiple range test.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of the isolated species in this study have been deposited in The National Center for Biotechnology Information with the accession number OL655411, OL655412 and OR037291.All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Stamets, P. Growing gourmet and medicinal mushrooms. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press (1993).

Lacey, J. & Crook, B. Fungal and actinomycete spores as pollutants of the workplace and occupational allergens. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 32, 515–533 (1988).

Cotter, T. Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation: Simple to Advanced and Experimental Techniques for Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA (2014).

Stamets, P. Growing gourmet and medicinal mushrooms. (Ten speed press, 2011).

Chiozzi, V., Agriopoulou, S. & Varzakas, T. Advances, applications, and comparison of thermal (pasteurization, sterilization, and aseptic packaging) against non-thermal (ultrasounds, UV radiation, ozonation, high hydrostatic pressure) technologies in food processing. Appl. Sci. 12, 2202 (2022).

Jung, H., Kim, D.-B., Gweon, B., Moon, S.-Y. & Choe, W. Enhanced inactivation of bacterial spores by atmospheric pressure plasma with catalyst TiO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 93, 212–216 (2010).

Kumar, S., Pipliya, S., Srivastav, P. P. & Srivastava, B. Exploring the Role of Various Feed Gases in Cold Plasma Technology: A Comprehensive Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 7, 1–41 (2023).

Selcuk, M., Oksuz, L. & Basaran, P. Decontamination of grains and legumes infected with Aspergillus spp. and Penicillum spp. by cold plasma treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 5104–5109 (2008).

Moisan, M. et al. Low-temperature sterilization using gas plasmas: a review of the experiments and an analysis of the inactivation mechanisms. Int. J. Pharm. 226, 1–21 (2001).

Yang, X. et al. Effect of Cold Atmospheric Surface Microdischarge Plasma on the Inactivation of Fusarium moniliforme and Physicochemical Properties of Chinese Yam Flour. Food Bioprocess Technol. 17 (4), 1072-1085 (2023).

Yarabbi, H., Soltani, K., Sangatash, M. M., Yavarmanesh, M. & Zenoozian, M. S. Reduction of microbial population of fresh vegetables (carrot, white radish) and dried fruits (dried fig, dried peach) using atmospheric cold plasma and its effect on physicochemical properties. J. Agric. Food Res. 14, 100789 (2023).

Xu, H., Liu, C. & Huang, Q. Enhance the inactivation of fungi by the sequential use of cold atmospheric plasma and plasma-activated water: Synergistic effect and mechanism study. Chem. Eng. J. 452, 139596 (2023).

Karunanithi, S., Guha, P. & Srivastav, P. P. Cold plasma-assisted microwave pretreatment on essential oil extraction from betel leaves: Process optimization and its quality. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 603–626 (2023).

Liang, W. et al. Comparison Study of DBD Plasma Combined with E-Beam Pre-and Post-treatment on the Structural-Property Improvement of Chinese Yam Starch. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 1–17 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Combined effects of vitamin C and cold atmospheric plasma-conditioned media against glioblastoma via hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 194, 1–11 (2023).

Baik, K. Y., Jo, H., Ki, S. H., Kwon, G.-C. & Cho, G. Synergistic Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide and Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma-Jet for Microbial Disinfection. Appl. Sci. 13, 3324 (2023).

Cerioni, L., de los Ángeles Lazarte, M., Villegas, J. M., Rodríguez-Montelongo, L. & Volentini, S. I. Inhibition of Penicillium expansum by an oxidative treatment. Food Microbiol. 33, 298–301 (2013).

Martyny, J. W. et al. Aerosolized sodium hypochlorite inhibits viability and allergenicity of mold on building materials. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116, 630–635 (2005).

Ver Kuilen, S. D. & Marth, E. B. Sporicidal action of hypochlorite on conidia of Aspergillus parasiticus. J. Food Prot. 43, 784–788 (1980).

Araujo, R., Gonçalves Rodrigues, A. & Pina-Vaz, C. Susceptibility pattern among pathogenic species of Aspergillus to physical and chemical treatments. Med. Mycol. 44, 439–443 (2006).

Ribeiro, M. S. S. et al. Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite and peracetic acid against Aspergillus nomius in Brazil nuts. Food Microbiol. 90, 103449 (2020).

Yang, C. Y. Comparative studies on the detoxification of aflatoxins by sodium hypochlorite and commercial bleaches. Appl. Microbiol. 24, 885–890 (1972).

Slaughter, R. J., Watts, M., Vale, J. A., Grieve, J. R. & Schep, L. J. The clinical toxicology of sodium hypochlorite. Clin. Toxicol. 57, 303–311 (2019).

Clarkson, R. M. & Moule, A. J. Sodium hypochlorite and its use as an endodontic irrigant. Aust. Dent. J. 43, 250–256 (1998).

Govaert, M., Smet, C., Verheyen, D., Walsh, J. L. & Van Impe, J. F. M. Combined effect of cold atmospheric plasma and hydrogen peroxide treatment on mature Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella Typhimurium biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2674 (2019).

Mai-Prochnow, A., Murphy, A. B., McLean, K. M., Kong, M. G. & Ostrikov, K. K. Atmospheric pressure plasmas: infection control and bacterial responses. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 43, 508–517 (2014).

Graves, D. B. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 45, 263001 (2012).

Waskow, A. et al. Characterization of efficiency and mechanisms of cold atmospheric pressure plasma decontamination of seeds for sprout production. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3164 (2018).

Basaran, P., Basaran-Akgul, N. & Oksuz, L. Elimination of Aspergillus parasiticus from nut surface with low pressure cold plasma (LPCP) treatment. Food Microbiol. 25, 626–632 (2008).

Los, A. et al. Improving microbiological safety and quality characteristics of wheat and barley by high voltage atmospheric cold plasma closed processing. Food Res. Int. 106, 509–521 (2018).

Suhem, K., Matan, N., Nisoa, M. & Matan, N. Inhibition of Aspergillus flavus on agar media and brown rice cereal bars using cold atmospheric plasma treatment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 161, 107–111 (2013).

Devi, Y., Thirumdas, R., Sarangapani, C., Deshmukh, R. R. & Annapure, U. S. Influence of cold plasma on fungal growth and aflatoxins production on groundnuts. Food Control. 77, 187–191 (2017).

Zahoranová, A. et al. Effect of cold atmospheric pressure plasma on the wheat seedlings vigor and on the inactivation of microorganisms on the seeds surface. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 36, 397–414 (2016).

Kim, J. E., Lee, D.-U. & Min, S. C. Microbial decontamination of red pepper powder by cold plasma. Food Microbiol. 38, 128–136 (2014).

Butman, M. F. et al. Synergistic effect of dielectric barrier discharge plasma and TiO2-pillared montmorillonite on the degradation of rhodamine B in an aqueous solution. Catalysts. 10, 359 (2020).

Mitrović, T., Tomić, N., Djukić-Vuković, A., Dohčević-Mitrović, Z. & Lazović, S. Atmospheric Plasma Supported by TiO 2 Catalyst for Decolourisation of Reactive Orange 16 Dye in Water. Waste Biomass Valorization. 11, 6841–6854 (2020).

Zhou, R. et al. Synergistic effect of atmospheric-pressure plasma and TiO2 photocatalysis on inactivation of Escherichia coli cells in aqueous media. Sci. Rep. 6, 39552 (2016).

Cortesão, M. et al. @article{shishodia2020sem, title={SEM and qRT-PCR revealed quercetin inhibits morphogenesis of Aspergillus flavus conidia via modulating calcineurin-Crz1 signalling pathway}, author={Shishodia, Sonia K and Tiwari, Shraddha and Hoda. Shanu and Vijayaraghav. Front. Microbiol. 12, 177 (2021).

Shishodia, S. K., Tiwari, S., Hoda, S., Vijayaraghavan, P. & Shankar, J. SEM and qRT-PCR revealed quercetin inhibits morphogenesis of Aspergillus flavus conidia via modulating calcineurin-Crz1 signalling pathway. Mycology. 11, 118–125 (2020).

Lin, C.-M. et al. The application of novel rotary plasma jets to inhibit the aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus flavus and the spoilage fungus, Aspergillus niger on peanuts. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 78, 102994 (2022).

Rossi-Fedele, G., Guastalli, A. R., Doğramacı, E. J., Steier, L. & De Figueiredo, J. A. P. Influence of pH changes on chlorine-containing endodontic irrigating solutions. Int. Endod. J. 44, 792–799 (2011).

Winterbourn, C. C. Comparative reactivities of various biological compounds with myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-chloride, and similarity of oxidant to hypochlorite. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-General Subj. 840, 204–210 (1985).

Beever, R. E., Redgwell, R. J. & Dempsey, G. P. Purification and chemical characterization of the rodlet layer of Neurospora crassa conidia. J. Bacteriol. 140, 1063–1070 (1979).

Winter, J., Ilbert, M., Graf, P. C. F., Özcelik, D. & Jakob, U. Bleach activates a redox-regulated chaperone by oxidative protein unfolding. Cell. 135, 691–701 (2008).

van Bergen, L. A. H., Roos, G. & De Proft, F. From thiol to sulfonic acid: modeling the oxidation pathway of protein thiols by hydrogen peroxide. J. Phys. Chem. A. 118, 6078–6084 (2014).

Deborde, M. & Von Gunten, U. R. S. Reactions of chlorine with inorganic and organic compounds during water treatment—kinetics and mechanisms: a critical review. Water Res. 42, 13–51 (2008).

Mendis, D. A., Rosenberg, M. & Azam, F. A note on the possible electrostatic disruption of bacteria. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 28, 1304–1306 (2000).

Ebrahimi, E., Hosseini, S. I., Samadlouie, H. R., Mohammadhosseini, B. & Cullen, P. J. Surface Barrier Discharge Remote Plasma Inactivation of Aspergillus niger ATCC 10864 Spores for Packaged Crocus sativus. Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 1–12 (2023).

Ohkawa, H. et al. Pulse-modulated, high-frequency plasma sterilization at atmospheric-pressure. Surf. coatings Technol. 200, 5829–5835 (2006).

Yang, L., Chen, J. & Gao, J. Low temperature argon plasma sterilization effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its mechanisms. J. Electrostat. 67, 646–651 (2009).

Sen, Y., Onal-Ulusoy, B. & Mutlu, M. Aspergillus decontamination in hazelnuts: Evaluation of atmospheric and low-pressure plasma technology. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 54, 235–242 (2019).

Siddique, S. S., Hardy, G. E. S. J. & Bayliss, K. L. Ultrastructural changes observed in Colletotrichum alienum conidia following treatment with cold plasma or plasma-activated water. Plant Pathol. 70, 1819–1826 (2021).

Dasan, B. G., Boyaci, I. H. & Mutlu, M. Nonthermal plasma treatment of Aspergillus spp. spores on hazelnuts in an atmospheric pressure fluidized bed plasma system: Impact of process parameters and surveillance of the residual viability of spores. J. Food Eng. 196, 139–149 (2017).

Sohbatzadeh, F., Mirzanejhad, S., Shokri, H. & Nikpour, M. Inactivation of Aspergillus flavus spores in a sealed package by cold plasma streamers. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 10, 99–106 (2016).

Cullen, P. J. et al. Translation of plasma technology from the lab to the food industry. Plasma Process. Polym. 15, 1700085 (2018).

Koban, I. et al. Synergistic effects of nonthermal plasma and disinfecting agents against dental biofilms in vitro. Int. Sch. Res. Not. no. 1, p. 573262 (2013).

China, S. et al. Rupturing of biological spores as a source of secondary particles in Amazonia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 12179–12186 (2016).

Greenspan, P., Mayer, E. P. & Fowler, S. D. Nile red: a selective fluorescent stain for intracellular lipid droplets. J. Cell Biol. 100, 965–973 (1985).

Kapuscinski, J. DAPI: a DNA-specific fluorescent probe. Biotech. Histochem. 70, 220–233 (1995).

Liao, X. et al. Inactivation mechanisms of non-thermal plasma on microbes: A review. Food Control. 75, 83–91 (2017).

Surowsky, B., Schlüter, O. & Knorr, D. Interactions of non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma with solid and liquid food systems: a review. Food Eng. Rev. 7, 82–108 (2015).

Prigione, V. & Marchisio, V. F. Methods to maximise the staining of fungal propagules with fluorescent dyes. J. Microbiol. Methods. 59, 371–379 (2004).

Misra, N. N. et al. Cold plasma in modified atmospheres for post-harvest treatment of strawberries. Food bioprocess Technol. 7, 3045–3054 (2014).

Mol, S. et al. Effects of Air and Helium Cold Plasma on Sensory Acceptability and Quality of Fresh Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Food Bioprocess Technol. 16, 537–548 (2023).

Wu, Y., Cheng, J.-H. & Sun, D.-W. Blocking and degradation of aflatoxins by cold plasma treatments: Applications and mechanisms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 109, 647–661 (2021).

Safaei, N., Alizadeh, A. A., Saeidi, A., Adam, G. & Rahimian, H. Molecular characterization and genetic diversity among iranian populations of Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of wheat headblight (2005).

White, T. J. et al. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guid. Methods Appl. 18, 315–322 (1990).

Samson, R. A. et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 78, 141–173 (2014).

Fernández-Miranda, E., Majada, J. & Casares, A. Efficacy of propidium iodide and FUN-1 stains for assessing viability in basidiospores of Rhizopogon roseolus. Mycologia. 109, 350–358 (2017).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saba Bakhtiarvandi: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. Hamid Reza Samadlouie: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Seyed Iman Hosseini : Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Shideh Mojerlou: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Patrick J. Cullen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Research involving plants

All authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakhtiarvandi, S., Samadlouie, H.R., Hosseini, S.I. et al. Enhanced disinfestation in grain spawn production through cold plasma and sodium hypochlorite synergy. Sci Rep 14, 28718 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77465-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77465-9