Abstract

Adolescence is a time when important changes occur in behavioral development, and previous studies have confirmed the relationship between excessive Internet use and decreased oral health behavior. Our purpose is to identify the indirect effects and behavioral factors of smartphone screen time on the caries symptom experience of adolescents. Using data from the 16–17th Korea youth risk behavior web based survey (2020–2021), we investigated the smartphone screen time of 109,796 students in middle school 1st to high school 3rd. Adolescents who used smartphones more than 6 h per week were 28% more likely to experience caries symptoms than those who used smartphones less than 2 h (odds ratio = 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.22–1.35). Those who consumed cariogenic drinks more than once a day were 25% more likely to experience caries symptoms, and those who brushed their teeth less than once a day were 26% more likely to experience caries symptoms (odds ratio = 1.25, 1.26; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.46, 1.06–1.51). Excessive smartphone screen time is associated with addictive eating habits and reduced physical activity that increase cariogenic dietary behaviors, and decrease oral health behaviors. It suggests that excessive smartphone use indirectly related to the experience of caries symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pew Research, a U.S. market researcher, conducted a survey of 18 countries on smartphone ownership rates in 2022, and found that South Korea’s smartphone ownership rate is 98% and those aged 18 to 29 are 100%1. This means that young people’ use of smartphones is widespread in Korea. Although smartphones also have the benefit of improving productivity and enabling social networking to help high social support and emotional health2,3, it’s important to note that smartphones are being abused today and this can cause addiction4.

Given these concerns, technological changes are now prompting a redefinition of behavioral addiction, such as excessive smartphone use5. Problematic smartphone use is defined as a form of behavior, which is characterized by compulsive use of devices, resulting in physical, psychological, or social impact6,7. Although various studies have been conducted on the effects of smartphone addiction8,9,10,11, there is still a lack of evidence to help evaluate the balance between the benefits and risks of smartphone addiction to human health12.

Moreover, smartphone addiction is perceived similarly to internet addiction, and duration of using the internet affects smartphone addiction and internet addiction13. Internet addiction is particularly vulnerable to adolescents who experience major changes in emotional, cognitive, and behavioral development14,15. Dental health is one of the least addressed oral care needs in adolescents, a period of increased sugar intake and nicotine initiation16. In a previous study using KYRBS, excessive or problematic Internet use was found to be associated with poorer oral health behaviors17,18. Other countries discovered poor clinical outcomes, as well as poorer oral health behaviors associated with internet addiction19. In southwestern Japan, it was suggested that Internet addiction affects dental caries through unhealthy lifestyle behaviors20.

However, compared to the evidence of internet addiction and oral health risks, the relationship between smartphone abuse and oral health is insufficient. Our purpose is to identify the indirect effect of smartphone screen time on adolescents’ experiences of caries symptoms and to find out the behavioral factors that act between excessive smartphone screen time and caries symptoms experience.

Results

Participant characteristics and caries symptom experience

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the participants according to the experience of caries symptoms. Among a total of 109,796 participants, 42,382 participants experienced caries symptoms, and 67,414 participants didn’t. Women and high school students had higher experience of caries symptoms than men and middle school students. Those who consumed soda drinks or sugary drinks 3 times a day experienced more caries symptoms than no symptoms. On the contrary, participants who brushed their teeth 2 times or more a day were higher experience of no symptoms than the experience of caries symptoms. The caries symptoms experience per week was 3.61 times higher in those who used smartphone more than 6 h than those who used less than 2 h (Table 1).

Impact of smartphone screen time on caries symptoms experience, and behaviors

The results of logistic regression analysis on the effects of average smartphone screen time on weekdays, weekends, and per week on caries symptoms experience, cariogenic dietary behaviors, and oral health behaviors are shown in Table 2. Those who used smartphone more than 6 h per week was 28% more likely to experience caries symptoms than those who use smartphone less than 2 h (OR = 1.28; 95% CI, 1.22–1.35). Among cariogenic dietary behaviors, participants who used smartphone more than 6 h per week was respectively 2.65 times or 1.78 times more likely to consume soda drinks or sugary drinks more than 3 times a day than participants who used smartphone less than 2 h (OR = 2.65; 95% CI, 2.00–3.52, OR = 1.78; 95% CI, 1.39–2.26). In oral health behaviors, participants who used smartphone more than 6 h per week was 52% more likely to brush their teeth less than once a day than participants who used smartphone less than 2 h (OR = 1.52; 95% CI, 1.38–1.67) (Table 2).

Association with smartphone screen time and caries symptoms experience among subgroups

Table 3 shows the results of a logistic regression analysis stratifying the experience of caries symptoms by subgroup according to smartphone screen time per week. In the group consuming cariogenic drinks once or more a day, those who used smartphones more than 6 h per week was 25% more likely to experience caries symptoms than those who used smartphones less than 2 h (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07–1.46). Among toothbrushing once or less a day group, participants who used smartphones more than 6 h was 26% more likely to experience caries symptoms than those who used smartphones less than 2 h (OR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06–1.51). By gender, both men and women showed an association between smartphone screen time and caries symptoms experience, but a distinct association was identified in women (OR = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.36–1.61). Middle school students were more likely to experience caries symptoms depending on their smartphone screen time than high school students (OR = 1.40; 95% CI, 1.31–1.50). Middle and high socioeconomic status found association with the experience of caries symptoms depending on the time spent using smartphones (OR = 1.36; 95% CI, 1.26–1.48, OR = 1.28; 95% CI, 1.18–1.37), but no association was found with low socioeconomic status (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the experience of caries symptoms according to smartphone screen time using data from the KYRBS, a representative sample survey of adolescents in Korea in 2021 and 2022. Previous studies have researched Internet usage time, oral health behavior, and oral hygiene, or smartphone screen time, mental health, and dietary patterns. We confirmed through the results of the study that the experience of caries symptoms increases as the smartphone screen time increases. In addition, it was discovered that an increase in caries symptoms experience as a result of smartphone screen time has the same tendency as an increase in cariogenic drinks consumption and a decrease in toothbrushing frequency (Table 2).

The number of teenagers (10–19 years old) at risk of smartphone overdependence continues to rise every year to 35.8% in 2020, 37.0% in 2021, and 40.1% in 202221. The percentage of smartphone content use by adolescents at risk of overdependence is 19.2% for games, 17.8% for movies/TV/video, 9.6% for mandatory education, 9.0% for messengers, and 8.4% for academic/business search21. It was found that 33.8% of games and 13.5% of animations/comics were ranked first for online video service contents used by teenagers21. Given this trend, it’s important to consider the broader implications of smartphone use. For instance, teenagers who frequently engage with games and videos on their smartphones are more likely to consume cariogenic drinks22, which is a crucial factor in oral health. Similarly, the correlation between screen time and dietary habits extends beyond television to include smartphones as well. Many longitudinal studies and systematic reviews, initially focused on TV viewing, have shown a high correlation between screen time and the consumption of energy-dense snacks or beverages23,24,25,26. Studies on smartphone use and dietary patterns suggested a correlation between high smartphone use and increased consumption of soda drinks and sweetened beverages27. Moreover, previous studies have found that consuming high-fat and high-sugar foods stimulates a reward system akin to drug dependence, increasing the risk of food poisoning28,29,30. These symptoms have also been reported in animal experiments31. According to a study on compulsive eating in obese rats and dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction, the acceleration of addiction was observed in rats with extended access to high-fat foods, and excessive consumption of foods that fit the taste induces neurobiological changes such as deregulation of dopamine receptors and leads to the development of compulsive eating habits32. This is related to the result of increasing dietary behavior of soda drinks and sugary drinks as smartphone screen time increases. Sugary drinks are a major contributor to free sugar, and increased free sugar intake is a risk factor for dental caries33. This supports the finding that consumption of cariogenic drinks once or more a day among those who used smartphones for more than 6 h 25% more likely to experience of caries symptoms than those who used smartphones less than 2 h (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07–1.46) (Table 3).

Conversely, an elevation in smartphone screen time is associated with an increased likelihood of infrequent toothbrushing (Table 2). This is estimated to be the effect of excessive smartphone use on the oral health behavior of life style. Adolescents without physical activity have a higher risk of smartphone addiction than adolescents with physical activity34. High-risk smartphone users were found to have less physical activity, such as the total number of steps taken or the average considered calories per day35. Not only excessive smartphone use but also smartphone addiction is direct leads to a decrease in physical activity36. Adolescents are susceptible to the influence of smartphone addiction, leading to a decrease in their physical activity levels37. High-frequency users who are consuming much time with smartphones gave up the opportunity doing physical activities to do sedentary behaviors and showed a broader pattern of sedentary behaviors pattern38. The positive relationship between heavy Internet use and secondary life style (sitting at least 6 h per day in the past 7 days) was discovered, while the negative relationship between heavy Internet use and dental check-up at least last per year was confirmed39. Therefore, excessive use of the Internet is associated with adverse oral health behaviors because it displaces time spent in oral hygiene care18, and Life style of poor oral health behavior can lead to caries symptom experience. This supports the result that individuals who used smartphones for more than 6 h daily were 26% more prone to experiencing symptoms of caries due to infrequent toothbrushing, compared to those who used smartphones for less than 2 h (OR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06–1.51) (Table 3).

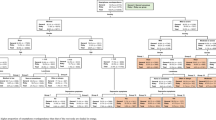

A conceptual model for the relationship between excessive smartphone use and caries symptoms experience was proposed based on the above: (1) Excessive smartphone use is a behavioral addiction and indirectly affects caries symptom experience. (2) Increased smartphone screen time has a direct impact on reduction of physical activity and compulsive eating habits. (3) Reduced physical activity has a direct effect on reducing oral health behaviors such as toothbrushing frequency, and compulsive eating habits has a direct effect on increasing consumption frequency of cariogenic drinks such as soda drinks & sugary drinks. (4) Decreased oral health behaviors and increased consumption frequency of cariogenic drinks directly affect caries symptom experience (Fig. 1).

In Table 3, the experience of caries symptoms increased as the time spent using smartphones increased for both men and women. As a result of the 2022 Smartphone Overdependence Survey, the risk of overdependence among women was 1.8% higher than that of men21. In women participants, the relationship between emotional dysregulation and Internet addiction, and between Internet use and Internet addiction was stronger than men40. Moreover, it was identified that the use of smartphones of middle school students had a higher impact on the experience of caries symptoms than high school students. Another report also showed middle school students had a 45.4% risk of overdependence on smartphones, 8.8% higher than high school students with 36.6%21. This indicates that the experience of caries symptoms due to smartphone screen time is more vulnerable in middle school students than in high school students. In the low socioeconomic status, there was no increase in the experience of caries symptoms according to smartphone screen time. High or middle socioeconomic status individuals tend to be more social activities than low socioeconomic status individuals, so the social disconnection of the low socioeconomic status may have mitigated the impact of smartphone screen time41. It is necessary to confirm that relationship between excessive smartphone use and behavior changes among women, middle school students, or adolescents of middle and high socioeconomic status.

The limitation of this study is that the KYRBS is a self-reported questionnaire and determination of the presence or absence of caries symptoms experience was analyzed based on questionnaire answers rather than clinical oral examination results. Therefore, social desirability bias and selection bias may have influenced the results. but it was shown that the same trend as the results of clinical oral examination20. The classification of smartphone screen time may not be appropriate because it was analyzed only for smartphone screen time without information on what purpose the smartphone was used and whether the smartphone was addicted. Since the purpose of using the smartphone was not considered, the smartphone screen time was broadly classified. And each group was not arbitrarily named normal, caution, risk, etc. This study is a cross-sectional study showing the relationship between smartphone screen time and experience of caries symptoms, so the causal relationship is not clear and should be addressed in a longitudinal study in the future.

In conclusion, this study suggests that excessive smartphone screen time is potentially related to an increase in the experience of caries symptoms. This may be due to a higher consumption of cariogenic drinks, like soda drinks and sugary drinks, and a reduction in oral health behaviors, such as the frequency of toothbrushing. Therefore, it would be beneficial to consider the development and implementation of guidelines for managing smartphone screen time, which could contribute to the prevention of dental caries symptoms in adolescents.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The data of this study used the 16–17th (2020–2021) of the Korea youth risk behavior web based survey42. KYRBS is a national representative survey conducted annually by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency and the Ministry of Education to identify the health behavior status of middle and high school students in Korea, conduct youth health promotion projects and evaluate them, and calculate health indicators. The participants of the survey are from the middle school 1st to the high school 3rd nationwide, and complex sampling is conducted hierarchically across the country depending on large cities, small and medium-sized cities, and county areas. The weighting is calculated by multiplying the inverse of the extraction rate, the inverse of the response rate, and a post-adjustment weighting rate. This process considers sample school and class extraction rates, grade-specific response rates, gender within each region, school level, and the sum of weights by grade. KYRBS is an anonymous, self-reported online survey that collects data. The number of participants in the 16th KYRBS was 54,948 and the number of participants in the 17th KYRBS was 54,848, a total of 109,796 (56,754 men and 53,042 women) were analyzed. Finally, data from 106,065 people (54,056 men and 52,009 women) who use smartphones on weekdays, 106,167 people (54,110 men and 52,057 women) who use smartphones on weekends, and 105,344 people (53,579 men and 51,765 women) who use smartphones per week were collected (Fig. 1). The Korea youth risk behavior survey (KYRBS) is a government-approved statistical survey (Approval No. 117058). The Institutional Review Board of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency waived ethical approval and parental informed consent requirements for this survey, in accordance with the 2015 Bioethics and Safety Act. Prior to initiating the survey, a supervising teacher was assigned at the designated school upon agreeing to participate in the survey, and students provided voluntary informed consent by clicking the participation button in the online survey. The study procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The research design was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Dentistry, Seoul National University (IRB approval No. S-D20230014). All methods were conducted in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations (Fig. 2).

Measures

In this study, sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, grade, parents’ education level, residence type, socioeconomic status, and academic achievement, cariogenic dietary behaviors such as consuming soda drinks or sugary drinks, oral health behaviors such as frequency of toothbrushing, and systemic health-related variables such as smoking or drinking experience were identified as confounding factors. For variables not specifically mentioned, the classification of the questionnaire was not modified. Smoking or drinking experience is defined a question asking whether or not you have ever smoked, and consists of (1) Yes, (2) No. Several variables were reclassified according to the purpose, and there were 6 response options on the type of residence, as follows (1) with family, (2) relatives’ house, (3) boarding house or living by oneself, (4) dormitory and (5) childcare facilities. It was divided into two categories such as (1) with family, (2) away from family. Self-perceived socioeconomic status and academic achievement had 5 response options such as (1) high, (2) middle high, (3) middle, (4) middle low, and (5) low. It was classified into 3 categories, as follows (1) high, (2) middle, and (3) low. High included high and middle high, and low included low and middle low. Cariogenic dietary behaviors (soda drinks and sugary drinks) originally had 7 response options, as follows (1) no drinking in the past 7 days, (2) 1–2 times a week, (3) 3–4 times a week, (4) 5–6 times a week, (5) once a day, (6) twice a day, (7) three times a day. It was analyzed as (1) intake of 3 or more times a day and (2) intake of less than 2 times a day. According to the questionnaire, soda drinks was defined as a carbonated drink excluding carbonated water, and sugary drinks were defined as sweet drinks (sweet ion drinks, sweet fruit juice, sweet coffee, etc.) excluding carbonated drinks and energy (high-caffeine) drinks. Cariogenic drinks, which are dietary behaviors, were divided into those who consumed soda drinks or sugary drinks at least once a day. The frequency of toothbrushing, which is an oral health behavior, had 10 response answers from 0 to 9 or more times. It was reclassified into (1) 1 time or less and (2) 2 times or more.

Smartphone screen time

Smartphone screen time is an item surveyed to identify Internet addiction in the KYRBS, and it was investigated in 2017 and began to be investigated again in 2020 (16th) except for 2018 and 2019. For the past 7 days, the question, "How many hours did you use your smartphone on average per day?" can be answered on weekdays and weekends, and it is divided into hours and minutes. Smartphone screen time was classified based on the criteria used in previous studies on Internet usage time17,43. Smartphone screen time of more than 6 h was included because, unlike previous studies on Internet usage, this measurement did not exclude time spent for academic purposes. The 4 categories of smartphone screen time on weekdays and weekends are as follows. (1) less than 2 h, (2) more than 2 h and less than 4 h, (3) more than 4 h and less than 6 h, (4) more than 6 h. To analyze weekly smartphone behavior, a weight of 5 was applied to weekdays and 2 to weekends, and then these values were combined. The average smartphone screen time was classified into 4 categories.

Caries symptoms experience

As for caries symptoms experience, in the oral health questionnaire of KYRBS, “have you experienced any of the following symptoms in the last 12 months?” To the following question: (1) Teeth hurt when drinking or eating cold or hot beverages or food, (2) Teeth throbbing or painful were composed of those who answered. Even if only one of the two questions was selected as yes, it was judged that there was an experience of caries symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Sampling weights were taken into consideration during statistical data analysis to ensure that the results could be representative of the entire Korean youth population. Using Chi-square test and frequency test to calculate the proportion and number of subgroups for category variables. The independent T-test was used for the continuous variable. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for confounding factors. Considering the complex sampling design, all missing values were treated as valid values during the multivariable logistic regression analysis. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, NY, USA).

Data availability

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/.

References

Wike, R. et al. Social media seen as mostly good for democracy across many nations, But U.S. is a major outlier. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/12/06/social-media-seen-as-mostly-good-for-democracy-across-many-nations-but-u-s-is-a-major-outlier/ (2022).

Cho, J. Roles of smartphone app use in improving social capital and reducing social isolation. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 18, 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0657 (2015).

Liu, Y. & Yi, H. Social networking smartphone applications and emotional health among college students: The moderating role of social support. Sci. Prog. 105, 368504221144439. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504221144439 (2022).

Loleska, S. & Pop-Jordanova, N. Is smartphone addiction in the younger population a public health problem?. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki) 42, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.2478/prilozi-2021-0032 (2021).

Kardefelt-Winther, D. et al. How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours?. Addiction 112, 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13763 (2017).

Achangwa, C., Ryu, H. S., Lee, J. K. & Jang, J. D. Adverse effects of smartphone addiction among university students in South Korea: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 11, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010014 (2022).

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C. & Hall, B. J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 207, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030 (2017).

Karishma, et al. Smartphone addiction and its impact on knowledge, cognitive and psychomotor skills among dental students in India: An observational study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1330_22 (2023).

Alzhrani, A. M. et al. The association between smartphone use and sleep quality, psychological distress, and loneliness among health care students and workers in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 18, e0280681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280681 (2023).

Ladeira, B. M. et al. Pain, smartphone overuse and stress in physiotherapy university students: An observational cross-sectional study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 34, 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2023.04.018 (2023).

Pei, Y. P. et al. The association between problematic smartphone use and the severity of temporomandibular disorders: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 10, 1042147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1042147 (2022).

Lin, C. Y., Ratan, Z. A. & Pakpour, A. H. Collection of smartphone and internet addiction. BMC Psychiatry 23, 427. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04915-5 (2023).

Tayhan Kartal, F. & Yabancı Ayhan, N. Relationship between eating disorders and internet and smartphone addiction in college students. Eat. Weight Disord. 26, 1853–1862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01027-x (2021).

Kaya, A. & Dalgiç, A. I. How does internet addiction affect adolescent lifestyles? Results from a school-based study in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 59, e38–e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.01.021 (2021).

Marin, M. G., Nuñez, X. & de Almeida, R. M. M. Internet addiction and attention in adolescents: A systematic review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 24, 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0698 (2021).

Silk, H. & Kwok, A. Addressing adolescent oral health: A review. Pediatr. Rev. 38, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2016-0134 (2017).

Do, K. Y., Lee, E. S. & Lee, K. S. Association between excessive Internet use and oral health behaviors of Korean adolescents: A 2015 national survey. Community Dent Health 34, 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_4107Do07 (2017).

Park, S. & Lee, J. H. Associations of internet use with oral hygiene based on national youth risk behavior survey. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak 29, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.5765/jkacap.2018.29.1.26 (2018).

Al-Ansari, A. et al. Internet addiction, oral health practices, clinical outcomes, and self-perceived oral health in young Saudi Adults. Sci. World J. 2020, 7987356. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7987356 (2020).

Iwasaki, M., Kakuta, S. & Ansai, T. Associations among internet addiction, lifestyle behaviors, and dental caries among high school students in Southwest Japan. Sci. Rep. 12, 17342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22364-0 (2022).

Ministry of Science and ICT; National Information Society Agency. The survey on smartphone over dependence. Ministry of Science and ICT; National Information Society Agency, Korea. (2022).

Lowry, R., Michael, S., Demissie, Z., Kann, L. & Galuska, D. A. Associations of physical activity and sedentary behaviors with dietary behaviors among US high school students. J. Obes. 2015, 876524. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/876524 (2015).

Pearson, N. & Biddle, S. J. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults. A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 41, 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.002 (2011).

Barr-Anderson, D. J., Larson, N. I., Nelson, M. C., Neumark-Sztainer, D. & Story, M. Does television viewing predict dietary intake five years later in high school students and young adults?. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-7 (2009).

Larson, N. I. et al. Fast food intake: longitudinal trends during the transition to young adulthood and correlates of intake. J. Adolesc. Health 43, 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.005 (2008).

Larson, N. I. et al. Fruit and vegetable intake correlates during the transition to young adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35, 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.019 (2008).

Kim, K. M., Lee, I., Kim, J. W. & Choi, J. W. Dietary patterns and smartphone use in adolescents in Korea: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 30, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.202103_30(1).0019 (2021).

Gearhardt, A. N., Davis, C., Kuschner, R. & Brownell, K. D. The addiction potential of hyperpalatable foods. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 4, 140–145. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874473711104030140 (2011).

Schulte, E. M., Avena, N. M. & Gearhardt, A. N. Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS ONE 10, e0117959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117959 (2015).

Schulte, E. M., Potenza, M. N. & Gearhardt, A. N. A commentary on the “eating addiction” versus “food addiction” perspectives on addictive-like food consumption. Appetite 115, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.10.033 (2017).

Robinson, M. J. et al. Individual differences in cue-induced motivation and striatal systems in rats susceptible to diet-induced obesity. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2113–2123. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.71 (2015).

Johnson, P. M. & Kenny, P. J. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2519 (2010).

Yang, Q. et al. Free sugars intake among chinese adolescents and its association with dental caries: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 13, 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030765 (2021).

Kim, J. & Lee, K. The association between physical activity and smartphone addiction in Korean adolescents: The 16th Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey, 2020. Healthcare (Basel) 10, 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040702 (2022).

Kim, S. E., Kim, J. W. & Jee, Y. S. Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 4, 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.028 (2015).

Lin, B., Teo, E. W. & Yan, T. The impact of smartphone addiction on Chinese university students’ physical activity: Exploring the role of motivation and self-efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 2273–2290. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S375395 (2022).

Al-Amri, A., Abdulaziz, S., Bashir, S., Ahsan, M. & Abualait, T. Effects of smartphone addiction on cognitive function and physical activity in middle-school children: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 14, 1182749. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1182749 (2023).

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., Sanders, G. J., Rebold, M. & Gates, P. The relationship between cell phone use, physical and sedentary activity, and cardiorespiratory fitness in a sample of U.S. college students. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 10, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-79 (2013).

Peltzer, K., Pengpid, S. & Apidechkul, T. Heavy internet use and its associations with health risk and health-promoting behaviours among Thai university students. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 26, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2013-0508 (2014).

Mo, P. K. H., Chan, V. W. Y., Chan, S. W. & Lau, J. T. F. The role of social support on emotion dysregulation and Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: A structural equation model. Addict. Behav. 82, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.027 (2018).

Zilioli, S., Fritz, H., Tarraf, W., Lawrence, S. A. & Cutchin, M. P. Socioeconomic status, ecologically assessed social activities, and daily cortisol among older urban African Americans. J. Aging Health 32, 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319856481 (2020).

Kim, Y. et al. Data resource profile: The Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey (KYRBS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1076–1076e. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw070 (2016).

Do, K. Y. & Lee, K. S. Relationship between problematic internet use, sleep problems, and oral health in Korean adolescents: A national survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091870 (2018).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Promotion R&D Project, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HS22C0065).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J.C. and S.J.K. contributed to conceptualization, and data curation was investigated by S.H.R. and H.J.K. Formal analysis was provided by SHR and funding acquisition was conducted by H.J.C. H.J.C. and S.J.K. contributed equally to the methodology. Project administration provided by S.J.K. and visualization conducted by S.H.R. The original draft wrote by S.H.R. and Z.L.W., and the review & editing was revised by S.H.R., H.J.C., and S.J.K. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryu, SH., Kwon, HJ., Wang, ZL. et al. Adolescents smartphone screen time and its association with caries symptoms experience from the Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey 2020–2021. Sci Rep 14, 26277 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77528-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77528-x