Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a major cause of food- and water-borne bacterial infections in humans. A key factor helping bacteria to survive adverse environmental conditions is biofilm formation ability. Nonetheless, the molecular basis underlying biofilm formation by C. jejuni remains poorly understood. Around thirty genes involved in the regulation and dynamics of C. jejuni biofilm formation have been described so far. We applied random transposon mutagenesis to identify new biofilm-associated genes in C. jejuni strain 81–176. Of 1350 mutants, twenty-four had a decreased ability to produce biofilm compared to the wild-type strain. Some mutants contained insertions in genes previously reported to affect the biofilm formation process. The majority of identified genes encoded hypothetical proteins. In the library of EZ-Tn5 insertion mutants, we found the cydB gene associated with respiration that was not previously linked with biofilm formation in Campylobacter. To study the involvement of the cydB gene in biofilm formation, we constructed a non-marked deletion cydB mutant together with a complemented mutant. We found that the cydB deletion-mutant formed a weaker biofilm of loosely organized structure and lower volume than the parent strain. In the present study, we demonstrated the role of the cydB gene in biofilm formation by C. jejuni.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

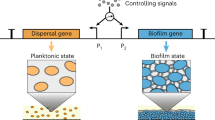

Campylobacter jejuni is a major cause of human food- and water-borne bacterial infections. In the European Union, campylobacteriosis is the most prevalent zoonosis and has been so since 20051. The primary source of human infections are undercooked poultry meat and poultry products, although cross-contamination of fresh produce and cooking utensils is also a possible transmission route2. Campylobacteriosis is usually manifested by fever, severe abdominal pain, and diarrhea. In a minority of patients, postinfectious sequellae may occur, including Miller-Fisher or Guillain-Barré syndromes 3. The bacterium cannot grow under 30ºC, requires a reduced oxygen atmosphere, and is sensitive to desiccation, high/low temperatures, osmotic and acid stress. The survival mechanism of Campylobacter in the natural and food processing environment is not clear. Scientists have postulated that biofilm formation is a relevant survival strategy under unpropitious conditions. Biofilm is a community of surface-attached microorganisms of one or more species enclosed in a self-produced extracellular matrix. Extracellular matrix composition varies by species but typically consists of DNA, proteins, and extracellular polysaccharides (EPS)4. Biofilm formation is an intricate process in which cells switch from planktonic growth mode to the sessile one. It is a multi-step process triggering specific mechanisms in bacteria. The mechanisms contributing to genetic and physiological heterogeneity involve genotypic variation caused by mutation and selection and adaptation to local environmental conditions, leading to differences in gene regulation. According to estimates, over 99% of bacteria in natural environments exist as biofilms rather than in planktonic cells. In such a community, bacteria are much more resistant to adverse environmental factors and antimicrobials 5. Although C. jejuni seems to be a poor biofilm initiator and forms monospecies biofilm under specific growth conditions, it can survive in the environment by forming mixed biofilms with other microorganisms6. Campylobacter biofilms are present in many natural niches, including poultry houses, slaughterhouses, and numerous aquatic environments. As a result, Campylobacter might be transmitted from the environment to and within poultry farms, potentially contributing to pathogenesis in humans7,8. The molecular basis underlying biofilm formation by Campylobacter lags behind that of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Escherichia coli. The first stage of biofilm formation in C. jejuni is flagellum-mediated, whereas extracellular DNA and DNA-binding proteins are essential for biofilm maturation9. Already identified motility-associated genes affecting biofilm formation in C. jejuni include genes encoding flagellins flaA, flaB, the filament cap fliD, the basal body flgG, flgG2, cell adhesion flaC, alternative sigma factor fliA, putative flagellar gene fliS, regulated by flhA10,11 and Campylobacter bile resistance regulator cbrR12. Genes involved in quorum sensing, e.g., luxS encoding autoinducer-2, chemotaxis, e.g., cheA, cheY, cheW, and cheV as well as cell surface modification, including the waaF heptosyltransferase, the lgtF LPS biosynthesis glycosyltransferase, the pglB oligosaccharyltransferase, peb4 antigenic virulence factor and pgp1 required for peptidoglycan modification were also found to be essential for biofilm formation13,14,15,16,17,18. Stress response genes also play a critical role in C. jejuni biofilm formation, including ahpC (alkyl hydroxide reductase), katA (catalase A), perR (peroxide stress response regulator), cosR (Campylobacter oxidative stress regulator), csrA (carbon starvation regulator), spoT (stringent response regulator), cprRS (Campylobacter planktonic growth regulator), ppk1-2 (polyphosphate kinase1, 2), and phoX (alkaline phosphatase)19,20,21,22,23,24. However, biofilm formation is a complex process, and there have not been saturating screens for genes involved in biofilm synthesis. One approach allowing the identification of potential biofilm-associated genes is a random transposon mutagenesis. Random transposon libraries are usually produced using mariner-based transposons or Tn5-based vectors. Tn5 vectors are active in a wide range of bacterial species. Tn5 transposons have been used to study biofilm process in E. coli, P. putida, S. epidermidis, L. monocytogenes and C. jejuni25,26,27,28,29.

The present study aimed to study the role of the cydB gene, identified using random transposon mutagenesis, in biofilm formation by C. jejuni.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The study was conducted on C. jejuni 81–17630. The strain was stored at − 80 °C in 15% glycerol. Prior to the experiments, C. jejuni 81–176 was subcultivated on Mueller–Hinton (MH) agar for 24 h at 42 °C under microaerobic conditions (85% N2, 5% O2, 10% CO2). The strains were then plated onto fresh MH agar supplemented with 20 µg/ml cefoperazone, 10 µg/ml vancomycin, 2 µg/ml amphotericin B and incubated under the same conditions. Liquid cultures of C. jejuni were grown in MH broth (MHB) and cultured in microaerobic environment.

Electrocompetent C. jejuni cells

C. jejuni 81–176 cells for electroporation were prepared as described previously21. Briefly, bacteria of OD600 0.35–0.4 were incubated on ice for 30 min and were centrifuged at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was washed with sterile cold distilled water and three times with ice-cold 10% glycerol and finally resuspended in 40 μl of GYT medium (10% glycerol, 0.125% yeast extract, 0.25% tryptone).

Generation of transposon library

Random transposon mutagenesis was performed using the EZ-Tn5™ < KAN-2 > Insertion Kit (Lucigen). Competent C. jejuni 81–176 cells were electroporated with 1 μl of transposome. Electroporation was performed in Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Xcell (2.5 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω). Following electroporation, the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of MHB, transferred on blood MH agar and allowed to recover for 6 h at 42 °C in a microaerobic atmosphere. MH agar with kanamycin (30 μg/ml) was used to select the transformants.

Identification of transposon-interrupted genes

Genomic DNA from mutants was extracted using Master Pure DNA Purification Kit (Lucigen). Transposon-interrupted genes were determined by sequencing flanking DNA following amplification of the region using the arbitrary primer PCR31. The resulting product was visualized by electrophoresis and single bands were sent for sequencing.

Biofilm assay

Single colonies of bacteria were grown in MHB for 2 days. Next, bacteria were diluted to OD600 = 0.2 and incubated statically for 72 h at 42º C in a microaerobic atmosphere in 96-well plates. The crystal violet (CV) method described by Fields and Thompson (2008) was used to assess biofilm formation. Briefly, bacterial suspension was aspirated, wells were washed with water, stained with CV, rinsed 3 times with water. The biofilm was dissolved in 80% DMSO and absorbance was measured at 570 nm. At least three experiments in triplicate were conducted for each strain.

Construction of a ΔcydB mutant

The generation of the ΔcydB mutant of C. jejuni 81–176 strain was based on streptomycin counterselection system developed by Rathbun et al.32. First, the cydB gene was amplified using the cydB-F and cydB-R primers, and the resulting product was cloned into the pCR II-TOPO vector. The resulting plasmid pJK101 was then subjected to inverse PCR using primers cydB- invF and cydB-invR. The amplified product was digested (AgeI/DpnI ) and autoligated generating a new plasmid pJK102. Primers rpsLcat-F and rpsLcat-R were used to amplify the rpsLcat cassette (StrS, CmR) from pKR02132(Table 1). The pJK101 plasmid and rpsLcat cassette were cut with restriction enzymes (AgeI/NheI ) and ligated create pJK103. Next, a spontaneous derivative of streptomycin-resistant C. jejuni strain 81–176 was electroporated with the mutant allele and plated on MH agar with chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml). The antibiotic resistance cassette was replaced by electroporation of transformants (CmR StrS) with the pJK102 plasmid and selection on MH agar with 500, 1000, 2000 µg/ml streptomycin. Successful deletion of the cydB gene was confirmed by screening the mutant with PCR primers cydBspr- F and cydBspr-R.

Complementation of ΔcydB mutant

To ensure that the observed phenotype of the mutant strain is specific to the deleted region of interest, complementation of the mutant with the wild copy of the gene was performed. Briefly, the cydB gene was amplified with primers cydB-compF and cydB-compR and inserted into the vector pRY112 (CmR) (kindly provided by dr Hendrixson). The resulting plasmid CM- 1 was then introduced into E. coli DH5α/pRK212.1 donor strain (kindly provided by dr Hendrixson). The plasmid was then introduced into 81–176 C. jejuni mutant strain by conjugation. Transconjugates were recovered on MH agar with streptomycin (100 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (10 µg/ml ) and trimethoprim (10 µg/ml). The isolated CM-1 plasmid was sent for sequencing.

Bold capitals show the sequence of restriction enzyme sites, while underline shows the Pcat promoter sequence.

Biofilm analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The biofilm for SEM analysis was prepared using the adsorption-incubation method described by Krzyżek et al. 33. Briefly, 2 ml of bacterial suspension (OD600 0.2) in MHB was added into a 6-well plate containing MHA and incubated for 3 days. The supernatant was gently removed, and the agar fragments were rinsed with PBS to eliminate loosely adhered bacterial cells. Agar fragments with attached biofilms were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, washed three times in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, treated with increasing ethanol concentration gradient, sputtered with a carbon layer and observed with a Scanning Electron Microscope Auriga 60 (Oberkochen, Germany). For each strain two independent experiments were performed.

Biofilm analysis using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

The biofilm for CLSM was prepared as described Bronnec et al., 34. Briefly, 1 ml of bacterial suspension (OD600 0.5) in MHB was added into a 96-well plate and incubated for 2 h at 42 °C (85% N2, 5% O2, 10% CO2). Next, the supernatant was replaced by fresh MH broth and the incubation was continued for 3 days. Bacterial cells were stained with SYTO9 and PI according to manufacturer’s protocol (LIVE/DEAD kit, Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and washed with PBS. The biofilms were imaged as described by 35. The SYTO 9-labeled living cells were detected using 488 nm lasers (Zeiss/Leica) and 502–538 nm emission range. PI-labeled dead or apoptotic cells were visualized with 561 nm (Zeiss) or 552 nm (Leica) lasers and 575–625 nm emission range. Biofilm-containing areas within a well of a 96-multiwell plate were imaged as 3 × 3 or 4 × 6 mosaics with a 7 µm interval in Z axis. The images were thresholded based on a set intensity value and the biofilm area was quantified using FIJI/ImageJ’s Analyze Particles function in relation to the well area (expressed as a percentage). Two independent experiments were performed for each strain.

Biofilm formation in a microfluidic system

Adhesion and biofilm formation in continuous flow was analyzed using microfluidic Bioflux 1000z system (Fluxion Biosciences, Alamenda, USA) according to protocol described by Paluch et al. (2021) with minor modifications. One milliliter of bacterial suspension (108 CFU/ml) was placed in the 48-well plate and incubated for 1 min. Next, the flow initiated at 0.2 dyn per 1 cm2 was initiated 36. The plate was incubated for 48 h at 42 °C (85% N2, 5% O2, 10% CO2). The analysis of images were performed using Image J software. For each strain three independent experiments in triplicate were conducted.

Motility test

To assess motility, a single colony was grown in MHB until OD600 = 0.2. Then the inoculum (1 µl) was stabbed using 10 µl pipette into the middle of a 9 -cm petri dish containing 25 ml of 0.4% agar MH and incubated overnight at 42º C in a microaerobic atmosphere32.

Growth curve

Overnight cultures of C. jejuni were harvested and diluted in MHB to OD600 = 0.05 and incubated at 42 °C under a microaerobic atmosphere. Samples were collected every 3 h and the OD600 values were measured to compare the growth of studied strains.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13.1. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. To assess the significance of the observed differences, one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test were used for Ez-Tn5 mutants. ANOVA Kruskal–Wallis with Bonferroni correction was used to determine whether differences in biofilm formation between the cydB mutant, the wild type, and the complemented strain are significant. A one-way ANOVA was used to evaluate whether differences in the motility were significant, whereas a multivariate ANOVA was used for viability and growth curves. Significance was set at a level of p < 0.05.

Results

Transposon mutagenesis of C. jejuni

To identify genes that are involved in biofilm formation, a transposon library of C. jejuni 81–176 was constructed and the biofilm production ability of individual mutants compared to the wild-type strain was assessed. Nearly 1350 mutants were generated. Twenty-four mutants displayed a significant decrease in biofilm formation compared to wild type (2.46- to 8.84-fold) (Fig. 1). Biofilm-compromised mutants contained interruptions in genes related to motility, metabolism, glycosylation, membrane transport, and respiration. We identified new genes not previously linked to biofilm formation in C. jejuni, including the cydB encoding cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase (Table 2). Since most genes encoded hypothetical or putative proteins, further study was focused on the confirmation of the cydB role in the biofilm formation process.

Biofilm formation of C. jejuni 81–176 Tn5 mutants based on CV staining of cells after 72 h of growth. The data show mean absorbance relative to the wild type strain. Error bars show the standard deviations from at least three independent experiments. Statistically significant results were considered when p-value < 0.05. Black bars show the cydB gene mutant and wild type strain.

Effect of cydB deletion on biofilm formation

To determine the role of the cydB gene in biofilm formation the biofilm formation abilities of C. jejuni 81–176 wild type, ΔcydB, and comp-cydB were compared. The ΔcydB mutant had significantly (p < 0.05) reduced capacity to produce biofilm than either the wild type strain or complemented mutant (Fig. 2A). The OD570 measurements for the wild type, the mutant and the complemented mutant were 0.46 ± 0.09, 0.18 ± 0.06 and 0.48 ± 0.11, respectively. The ΔcydB mutant formed a very weak biofilm of loose structure on the bottoms of the wells (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, the biofilm of the wild type and the complemented strain was dense.

A. Biofilm formation of C. jejuni strains. Bacterial suspensions (OD600 = 0.2) of 81–176 WT, ΔcydB, and comp-cydB strains were incubated statically for 72 h at 42 °C, and stained with CV. Then OD570 was measured to quantify biofilm formation. An asterisk represents statistical significance (P < 0.05). B Biofilms on plate after 72-h incubation based on CV staining.

To confirm the CV staining data, SEM was used to visualize the biofilm structure. In addition, the biofilm under dynamic conditions and cell viability were assessed. SEM revealed three-dimensional C. jejuni biofilm architecture that correlated with CV staining. The wild-type C. jejuni 81–176 strain and comp-cydB strain formed very dense mature biofilm consisting of huge agglomerates. These biofilms were practically indistinguishable. In contrast, the ∆cydB mutant formed a loosely organized biofilm of a much smaller volume and irregular structure (Fig. 3). Only in some areas cell aggregates were visible, whereas void spaces with single cells dominated. The ∆cydB biofilm appeared more compact and less dense, as compared to the more uniform biofilm lawns of the wild-type and comp-cydB strains. All studied biofilms contained two cell morphology types, i.e., typical spiral shape and coccoidal shape, indicating the VBNC state. In addition, tubular criss-crossed network-like structures, probably corresponding to flagella, were visible (Fig. 3).

CLSM images allowed estimation of live and dead cells within the biofilm (Fig. 4A, 4B). The biofilm of the parent strain consisted of 70,3% ± 8,58% of viable cells (green) and 29,7% ± 8,58% of dead cells (red). The ΔcydB mutant biofilm contained 87,77% ± 1,81% of viable cells and 12,23% ± 1,81% of dead cells. The percentage of live and dead cells in the biofilm of comp-cydB strain was 84,75% ± 7,05% and 15,25% ± 7,05%, respectively. The differences in viability between studied strains were not significant (Fig. 4B).

The Microfluidic Bioflux system allowed biofilm assessment under flow conditions (Fig. 5). For the wild-type strain systematic and gradual increase in the biofilm surface was noted. After 22 h biofilm reached over 50% of the microfluidic channel. Then further systematic increase in the biofilm surface was observed, reaching over 90% of the channel after 48 h. In the case of the ΔcydB mutant, the biofilm formation was very limited during the whole experiment, reaching only 2–4% of the channel surface. In contrast, the complemented strain increased biofilm formation after 26 h. Between 28 and 30 h, the biofilm surface expanded five times. Then systematic increase in the biofilm surface was found, reaching over 75% of the channel.

Effect of cydB deletion on the growth and motility of C. jejuni

The deletion of the cydB gene did not affect C. jejuni growth. There were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the OD600 values between the mutant, the parent strain, and the complemented mutant at all time points (Fig. 6). There were also no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the motility between the mutant, the wild-type strain, and the complemented mutant after 24 h (Fig. 7). The growth zones for the mutant, the parent strain, and the complemented mutant were 20.5 ± 1.38, 21.92 ± 1.44, and 21.33 ± 1.3, respectively.

Discussion

C. jejuni is the major cause of bacterial, watery diarrhea in humans worldwide. Due to specific growth requirements and vulnerability, the actual number of C. jejuni infections might be underestimated. Campylobacter seems to have also unique molecular mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis, persistence, and survival2. In contrast to other enteropathogens, C. jejuni is naturally competent for DNA transformation and thereby may easily take up foreign DNA, including antibiotic resistance genes37. A substantial role in the survival and persistence in the environment plays biofilm formation. Since in the biofilm the pathogen transfers and acquires antibiotic-resistance genes more often than in planktonic cells, it is a relevant reservoir of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and a serious threat to public health8. For this reason, studying the mechanism helping survive C. jejuni in the environment, including biofilm formation, is of great importance. Around thirty genes responsible for the regulation and dynamics of C. jejuni biofilm formation have been described38. Studies on P. aeruginosa or E. coli have shown that this process is multifactorial, orchestrated by the expression of many genes belonging to various metabolic pathways. In P. aeruginosa, a kinetic model of the metabolic network on genome scale revealed 239 reactions whose inhibition resulted in either a decrease or increase in biofilm formation39. In E. coli Niba et al.40 identified 110 genes which knockout resulted in reduced biofilm formation. More, microarray studies revealed 2504 differentially regulated genes in the mature biofilm of P. aeruginosa41 and 1292 differentially expressed genes in the biofilm of E. coli cells42. A recent study by Tram et al.18, using a comparative omics approach, has revealed distinct variations between the biofilm and planktonic state of C. jejuni. The transcriptome analysis showed 620 genes regulated expressed in biofilm conditions, confirming the complexity of the biofilm formation process in C. jejuni18. To identify new genes linked with biofilm formation we used a commercial transposon mutagenesis system, i.e., the EZ-Tn5 Transposome. Tn5 originated as bacterial transposons and has no target sequence requirement for insertion, potentially allowing higher insertion density than the mariner transposition system43. Lin et al.44 have demonstrated that Tn5 transposon is an efficient tool for the systematic characterization of functionally relevant genes in C. jejuni. Mandal et al.45 have used Tn5 technology in Campylobacter jejuni for essential genome studies. In turn, Teh et al.28 applying this method, have screened biofilm-associated genes in C. jejuni. The authors have generated only 22 mutants on one out of 7 C. jejuni strains, suggesting a strain-dependent transposon efficiency28. In the present study, we constructed the library of over one thousand C. jejuni 81–176 mutants, which were assessed for biofilm formation ability compared to the parent strain. Twenty-four mutants displayed a significant decrease (2.46- to 8.84-fold) in biofilm formation compared to the wild type. Some mutants contained insertions in genes previously reported to affect biofilm formation, such as motility-associated genes flgG, pflA9,11 or the pglB gene involved in glycosylation14.This supports the reliability of EZ-Tn5 transposon mutagenesis. We have identified genes related to cell adhesion, metabolism, membrane transport, and respiration that were not previously linked with the biofilm formation in Campylobacter. The majority of these genes encode hypothetical proteins whose role in C. jejuni is not fully recognized or was not studied at all. The deletion of one gene, CJJ8176_1389, significantly decreased the colonization of chickens’ gastrointestinal tracts46. In the present paper, we focused on the impact of the cydB gene on biofilm formation by C. jejuni. This gene is associated with the respiratory chain and metabolism. In C. jejuni the cydB gene is located in the cydAB operon. In E. coli the cydABX gene cluster encodes cytochrome bd, a high-affinity quinol oxidase responsible for aerobic respiration in low-oxygen environments47.The authors have shown that the loss of cytochrome bd affected biofilm architecture. The cydAB genes knockout reduced the abundance of extracellular matrix and increased bacterial sensitivity to nitrosative and oxidative stress47. Further, Beebout et al.48 have revealed that the cytochrome bd loss also decreased biofilm resistance to antibiotics, indicating it as a possible target in the antibiofilm approach. In C. jejuni cydAB genes encode a cyanide-insensitive, low-affinity oxidase that was found to improve the survival of C. jejuni under microaerobic conditions 49. Jackson et al. have demonstrated that this oxidase is not relevant for C. jejuni growth but affects the cell viability in a microaerophilic atmosphere. The authors have suggested that this oxidase should be renamed CioAB (cyanide-insensitive oxidase) due to a lack of characteristic cytochrome bd features49. To confirm the role of this gene, we constructed a non-marked deletion mutant together with complementation. The mutation did not affect the motility, bacterial growth, and viability of cells that could influence the biofilm formation. We found that the deletion of the cydB gene significantly decreased biofilm formation ability. The mutant produced biofilm of loosely organized structure and much lower volume than the parent strain. The complementation restored the parental phenotype, proving that the observed effect is attributed exclusively to the cydB knockout. Microfluidic Bioflux system allowed us to investigate the dynamic of biofilm formation. For the parent strain and complemented strain, systematic and gradual increase in the biofilm surface was observed. The complemented strain triggered biofilm production later than the wild-type strain which can be explained by the necessary adjustment to environmental conditions and overdue expression of the cydB gene located on the plasmid. On the contrary, the biofilm formation by the knockout-mutant strain was very scarce during the whole experiment, reaching only 2–4% of the microfluidic channel surface. In the current study, we demonstrated for the first time the role of the cydB gene in the biofilm formation process in C. jejuni. We also showed that the EZ-Tn5 system is a reliable and effective tool for studying the biofilm formation mechanism in C. jejuni 81–176.

Conclusions

C. jejuni is one of the most important human pathogens. Despite its vulnerability to environmental stress, campylobacteriosis is the most prevalent zoonosis in the EU for over a decade. The biofilm lifestyle has been postulated to be a key factor contributing to the high prevalence of C. jejuni and its ability to overcome environmental stress. Since the mechanism underlying biofilm formation in C. jejuni is still not well recognized, there is a need for detailed research. In our study we showed that the EZ-Tn5 Transposome system is an efficient tool for exploring the molecular basis of biofilm formation. We identified a new gene, cydB, involved in biofilm formation by C. jejuni. By more fully understanding the mechanisms of C. jejuni biofilm formation, we hope to be able to rationally design biofilm-disrupting inhibitors.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences repository (DOI:https://doi.org/10.57755/dkrh-9228).

References

The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA Journal 20, (2022).

Turonova, H. et al. Biofilm spatial organization by the emerging pathogen Campylobacter jejuni: comparison between NCTC 11168 and 81–176 strains under microaerobic and oxygen-enriched conditions. Front Microbiol 6, (2015).

Young, K. T., Davis, L. M. & Dirita, V. J. Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 5, 665–679 (2007).

Brown, H. L., Hanman, K., Reuter, M., Betts, R. P. & van Vliet, A. H. M. Campylobacter jejuni biofilms contain extracellular DNA and are sensitive to DNase I treatment. Front Microbiol 6, (2015).

Jamal, M., Tasneem, U., Hussain, T. & Andleeb, S. Bacterial biofilm: its composition, formation and role in human infections. Res Rev J Microbiol Biotechnol 4, (2015).

Teh, A. H. T., Lee, S. M. & Dykes, G. A. Does Campylobacter jejuni form biofilms in food-related environments?. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 5154–5160 (2014).

Fields, J. A., Li, J., Gulbronson, C. J., Hendrixson, D. R. & Thompson, S. A. Campylobacter jejuni CsrA regulates metabolic and virulence associated proteins and is necessary for mouse colonization. PLoS One 11, e0156932 (2016).

Haddock, G. et al. Campylobacter jejuni 81–176 forms distinct microcolonies on in vitro-infected human small intestinal tissue prior to biofilm formation. Microbiology (N Y) 156, 3079–3084 (2010).

Svensson, S. L., Pryjma, M. & Gaynor, E. C. Flagella-mediated adhesion and extracellular DNA release contribute to biofilm formation and stress tolerance of Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS One 9, e106063 (2014).

Joshua, G. W. P., Guthrie-Irons, C., Karlyshev, A. V. & Wren, B. W. Biofilm formation in Campylobacter jejuni. Microbiology (Reading) 152, 387–396 (2006).

Kalmokoff, M. et al. Proteomic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni 11168 biofilms reveals a role for the motility complex in biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 188, 4312–4320 (2006).

Cox, C. A. et al. The Campylobacter jejuni response regulator and cyclic-Di-GMP binding CbrR is a novel regulator of flagellar motility. Microorganisms 10, 86 (2021).

Asakura, H., Yamasaki, M., Yamamoto, S. & Igimi, S. Deletion of peb4 gene impairs cell adhesion and biofilm formation in Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol Lett 275, 278–285 (2007).

Cain, J. A. et al. Proteomics reveals multiple phenotypes associated with N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol Cell Proteomics 18, 715–734 (2019).

Frirdich, E. et al. Peptidoglycan LD-Carboxypeptidase Pgp2 influences Campylobacter jejuni helical cell shape and pathogenic properties and provides the substrate for the DL-Carboxypeptidase Pgp1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 289, 8007–8018 (2014).

Naito, M. et al. Effects of sequential Campylobacter jejuni 81–176 lipooligosaccharide core truncations on biofilm formation, stress survival, and pathogenesis. J Bacteriol 192, 2182–2192 (2010).

Reuter, M., Ultee, E., Toseafa, Y., Tan, A. & van Vliet, A. H. M. Inactivation of the core cheVAWY chemotaxis genes disrupts chemotactic motility and organised biofilm formation in Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol Lett 367, (2021).

Tram, G. et al. Assigning a role for chemosensory signal transduction in Campylobacter jejuni biofilms using a combined omics approach. Sci Rep 10, 6829 (2020).

Candon, H. L., Allan, B. J., Fraley, C. D. & Gaynor, E. C. Polyphosphate kinase 1 is a pathogenesis determinant in Campylobacter jejuni. J Bacteriol 189, 8099–8108 (2007).

Drozd, M., Chandrashekhar, K. & Rajashekara, G. Polyphosphate-mediated modulation of Campylobacter jejuni biofilm growth and stability. Virulence 5, 680–690 (2014).

Fields, J. A. & Thompson, S. A. Campylobacter jejuni CsrA mediates oxidative stress responses, biofilm formation, and host cell invasion. J Bacteriol 190, 3411–3416 (2008).

McLennan, M. K. et al. Campylobacter jejuni biofilms up-regulated in the absence of the stringent response utilize a calcofluor white-reactive polysaccharide. J Bacteriol 190, 1097–1107 (2008).

Oh, E. & Jeon, B. Role of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) in the biofilm formation of Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS One 9, e87312 (2014).

Svensson, S. L. et al. The CprS sensor kinase of the zoonotic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni influences biofilm formation and is required for optimal chick colonization. Mol Microbiol 71, 253–272 (2009).

Chang, Y., Gu, W., Fischer, N. & McLandsborough, L. Identification of genes involved in Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation by mariner-based transposon mutagenesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 93, 2051–2062 (2012).

López-Sánchez, A. et al. Biofilm formation-defective mutants in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett 363, (2016).

Puttamreddy, S., Cornick, N. A. & Minion, F. C. Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis reveals a role for pO157 genes in biofilm development in Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933. Infect Immun 78, 2377–2384 (2010).

Teh, A. H. T., Lee, S. M. & Dykes, G. A. Identification of potential Campylobacter jejuni genes involved in biofilm formation by EZ-Tn5 transposome mutagenesis. BMC Res Notes 10, 182 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. SarZ is a key regulator of biofilm formation and virulence in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Infect Dis 197, 1254–1262 (2008).

Black, R. E., Levine, M. M., Clements, M. L., Hughes, T. P. & Blaser, M. J. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. Journal of Infectious Diseases 157, 472–479 (1988).

Garsin, D. A., Urbach, J., Huguet-Tapia, J. C., Peters, J. E. & Ausubel, F. M. Construction of an Enterococcus faecalis Tn 917 -mediated-gene-disruption library offers insight into Tn 917 insertion patterns. J Bacteriol 186, 7280–7289 (2004).

Rathbun, K. M., Hall, J. E. & Thompson, S. A. Cj0596 is a periplasmic peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase involved in Campylobacter jejuni motility, invasion, and colonization. BMC Microbiol 9, 160 (2009).

Krzyżek, P., Migdał, P., Grande, R. & Gościniak, G. Biofilm formation of Helicobacter pylori in both static and microfluidic conditions is associated with resistance to clarithromycin. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12, (2022).

Bronnec, V. et al. Adhesion, biofilm formation, and genomic features of Campylobacter jejuni Bf, an atypical strain able to grow under aerobic conditions. Front Microbiol 7, (2016).

Szyposzynska, A. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles from adipose tissue: unraveling their impact on primary ovarian cancer cells and their therapeutic opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 24, 15862 (2023).

Paluch, E. et al. Composition and antimicrobial activity of ilex leaves water extracts. Molecules 26, 7442 (2021).

Bae, J., Oh, E. & Jeon, B. Enhanced transmission of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni biofilms by natural transformation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 7573–7575 (2014).

Püning, C., Su, Y., Lu, X. & Gölz, G. Molecular mechanisms of Campylobacter biofilm formation and quorum sensing. in 293–319 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65481-8_11.

Vital-Lopez, F. G., Reifman, J. & Wallqvist, A. Biofilm formation mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa predicted via genome-scale kinetic models of bacterial metabolism. PLoS Comput Biol 11, e1004452 (2015).

Niba, E. T. E., Naka, Y., Nagase, M., Mori, H. & Kitakawa, M. A Genome-wide approach to identify the genes involved in biofilm formation in E. coli. DNA Research 14, 237–246 (2008).

Heacock-Kang, Y. et al. Novel dual regulators of Pseudomonas aeruginosa essential for productive biofilms and virulence. Mol Microbiol 109, 401–414 (2018).

Ranjith, K. et al. Global gene expression in Escherichia coli, isolated from the diseased ocular surface of the human eye with a potential to form biofilm. Gut Pathog 9, 15 (2017).

Barquist, L., Boinett, C. J. & Cain, A. K. Approaches to querying bacterial genomes with transposon-insertion sequencing. RNA Biol 10, 1161–1169 (2013).

Lin, J., Wang, Y. & Van Hoang, K. Systematic identification of genetic loci required for polymyxin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni using an efficient in vivo transposon mutagenesis system. Foodborne Pathog Dis 6, 173–185 (2009).

Mandal, R. K., Jiang, T. & Kwon, Y. M. Essential genome of Campylobacter jejuni. BMC Genomics 18, 616 (2017).

Johnson, J. G., Gaddy, J. A. & DiRita, V. J. The PAS domain-containing protein HeuR regulates heme uptake in Campylobacter jejuni. mBio 7, (2016).

Beebout, C. J. et al. Respiratory heterogeneity shapes biofilm formation and host colonization in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio 10, (2019).

Beebout, C. J., Sominsky, L. A., Eberly, A. R., Van Horn, G. T. & Hadjifrangiskou, M. Cytochrome bd promotes Escherichia coli biofilm antibiotic tolerance by regulating accumulation of noxious chemicals. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 35 (2021).

Jackson, R. J. et al. Oxygen reactivity of both respiratory oxidases in Campylobacter jejuni : the cydAB genes encode a cyanide-resistant, low-affinity oxidase that is not of the cytochrome bd type. J Bacteriol 189, 1604–1615 (2007).

Funding

This work was funded in part by National Science Centre (Poland) grant no. 2022/47/O/NZ7/01326. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission. Work was supported by the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (Poland), Bon doktoranta SD UPWr” no. N020/0001/21,National Institutes of Health,AI154078, Narodowe Centrum Nauki, 2022/47/O/NZ7/01326. Sciences (Poland) as the Ph.D. research program „Bon doktoranta SD UPWr” no. N020/0001/21 from the subsidy increased by the minister responsible for higher education and science for the period 2020–2026 in the amount of 2% of the subsidy referred to Art. 387 (3) of the Act of 20 July 2018 – Law on Higher Education and Science, obtained in 2019. Also supported by US National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIH/NIAID) grants AI154078 and AI103267 (To SAT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jakub Korkus: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Validation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Patrycja Sałata: Investigation, Data curation. Stuart Thompson: Conceptualization, Writing- review&editing, Funding acquisition. Emil Paluch: Investigation. Jacek Bania: Writing- review&editing. Ewa Wałecka-Zacharska: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing- original draft, Writing- review&editing, Project administration, Supervison, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korkus, J., Sałata, P., Thompson, S.A. et al. The role of cydB gene in the biofilm formation by Campylobacter jejuni. Sci Rep 14, 26574 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77556-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77556-7