Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the short-term variability of ocular biometric measurements and to analyze the factors associated with high variability of biometric values in patients with cataract. This retrospective study included 60 eyes of 60 patients who underwent ocular biometry twice with the IOLMaster 700 (March to November 2023). Ocular surface parameters included tear film break-up time (TBUT), corneal and conjunctival staining scores (CSS/ConSS). Refractive surprise was defined as a mean absolute error exceeding 0.5 diopter (D). Participants included 22 men and 38 women with a mean age of 70.6 ± 8.4 years. The variability of mean keratometric (K) values and astigmatism showed notable variability compared to axial length (mean K: 0.18 ± 0.17D, astigmatism: 0.21 ± 0.26D, axial length: 0.01 ± 0.01 mm). A decreased TBUT and increased CSS were significantly associated with high variability (≥ 0.25D) of mean K (p = 0.040/0.008). The high K variability group (≥ 0.25D) revealed a significantly higher incidence of refractive surprise (> 0.5D) compared with the low K variability group (< 0.25D) (45.5%/17.9%, p = 0.037). Preoperative lower TBUT and higher CSS influenced the variability of K values in ocular biometry and may be related with postoperative refractive surprise due to erroneous K values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cataract surgery is one of the most common surgeries performed worldwide1,2. With increasing patient expectations for postoperative visual outcomes, the calculation of intraocular lens (IOL) power has become increasingly important in cataract surgery3. Accurate measurement of ocular biometry is essential before cataract surgery, and efforts to minimize measurement variability are necessary for the accuracy of IOL power calculations and postoperative refractive outcomes3. In particular, improving the calculation and predictability of IOL power has become even more critical in regard to premium IOLs such as multifocal, extended depth of focus, and toric IOLs. In addition, IOL power calculation is also important in cases of prior corneal refractive surgery, keratoconus, and irregular cornea4.

The IOLMaster 700 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany), which uses swept-source optical coherence, has been widely used in clinical ophthalmologic practice5. This device can quickly measure various ocular biometric parameters such as axial length (AL), anterior chamber depth (ACD), corneal curvature, central corneal thickness, lens thickness, and pupil size. The IOLMaster 700 provides better biometric measurement acquisition rates and higher repeatability and reproducibility compared to partial coherence interferometry6,7. In addition, the IOLMaster 700 is particularly effective in obtaining biometric measurements in eyes with posterior subcapsular and dense nuclear cataracts5. Meanwhile, the more recent and updated IOL power calculation formulas such as the Barrett Universal II (BUII), the Emmetropia Verifying Optical (EVO), and the Kane formula have demonstrated superior results in postoperative refractive accuracy in several studies8,9. The BUII formula is a theoretical model proven to be one of the most accurate formulas and is therefore widely used in IOL power calculations worldwide10. Accordingly, the use of the BUII formula with the IOLMaster 700 has shown excellent results in the literature with a mean absolute error (MAE) within 0.5 diopter (D); however, the percentage of eyes with prediction errors within ± 0.5D using this technique is reported as 80–85%11,12,13. Hence, even with the latest biometry device and updated IOL power calculation formulas, a prediction error of 15–20% or more is possible. The main cause of this error may be related to inaccurate measurement and high variability of ocular biometrics, with ocular surface disease likely contributing significantly to this measurement error.

Previous studies have shown that an unstable tear film and ocular surface staining can lead to an uneven refractive surface, resulting in the production of abnormal optical aberrations14,15. These factors can also reduce the accuracy and repeatability of ocular biometric measurements14,15. Patients with tear hyperosmolarity had higher variability in mean keratometry (K) and corneal astigmatism, which could potentially cause errors in IOL power calculation14. The non-invasive break-up time (NIBUT) test average was also known to affect mean K and corneal astigmatism16. Although the importance of ocular surface management prior to cataract surgery has been emphasized, there have been few studies on how dry eye disease (DED) affects the accuracy of ocular biometric measurements and variability. In this study, we analyzed the variability of ocular biometric parameters measured twice with the IOLMaster 700 before cataract surgery and investigated the factors that influence the high variability of ocular biometric values.

Results

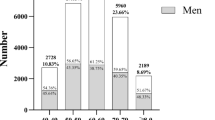

The demographic characteristics of the included patients with cataract are summarized in Table 1. This study included 60 participants with an average age of 70.6 ± 8.4 years, comprising 22 men and 38 women. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were present in 55.0% and 33.3% of the participants, respectively. The average meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) stage was 1.8 ± 0.4. Tear film break-up time (TBUT) averaged 3.7 ± 1.4 s. The corneal staining score [CSS, SICCA (Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance) score] and conjunctival staining score (ConSS, Oxford scheme) were 0.7 ± 0.6 and 0.8 ± 0.5 points, respectively17,18,19. Nuclear sclerosis grading was 3.0 ± 0.9 20. The interval between repetitive measurements was 17.1 ± 5.2 days.

The comparison between the two repetitive measurements using the IOLMaster 700 revealed no statistically significant differences across various parameters. AL, ACD, white-to-white diameter (WTW), amount of astigmatism, and K values were remarkably consistent between the first and second measurements taken using the IOLMaster 700 (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the differences of ocular biometric values between two repetitive measurements using the IOLMaster 700. For AL and ACD, the respective mean differences with standard deviations showed minimal variation at 0.01 ± 0.01 mm and 0.03 ± 0.04 mm, and the range was relatively consistent at 0–0.06 mm and 0–0.09 mm. However, the K values and corneal astigmatism amount exhibited a noticeable degree of difference, as reflected in both the mean differences with larger standard deviations and the wider range of values. The differences between the two measurements were 0.21 ± 0.21D (0.01–1.25D) in K1, 0.21 ± 0.23D (0–1.49D) in K2, 0.18 ± 0.17D (0–0.88D) in mean K, and 0.21 ± 0.26D (0–1.54D) in astigmatism amount. Differences in the steep axis of corneal astigmatism ranging between 10 degrees and 30 degrees were observed in 21.9% (7 of 32), and 9.4% (3 of 32) showed differences exceeding 30 degrees.

To investigate factors that influence the substantial variation in mean K error observed between the two measurements, we analyzed two groups: high K variability group (mean K difference ≥ 0.25D) and low K variability group (mean K difference < 0.25D). The comparison focused on age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, MGD stage, and dry eye signs. There was no statistically significant difference in age between the high and low K variability groups (high K: 71.7 ± 7.5 years, low K: 70.2 ± 8.7 years, p = 0.553). However, significant differences were observed in TBUT and CSS between the high and low K variability groups (TBUT - high K: 3.1 ± 1.3 s/low K: 4.0 ± 1.4 s/p = 0.040, CSS - high K: 1.1 ± 0.6 points/low K: 0.6 ± 0.6 points/p = 0.008). No significant difference was found in the ConSS between the two groups (0.9 ± 0.3 and 0.8 ± 0.5 points, respectively) (p = 0.500) (Table 4).

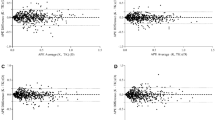

The mean emmetropic IOL power calculated from the first measurement was 20.74 ± 3.47D, while the mean emmetropic IOL power from the second measurement was 20.83 ± 3.47D (p = 0.017). After the first measurement, the percentage of patients with a change in implanted IOL power due to discrepancy between first and second measurements was 25% (15 patients). The IOL power changed by 0.5D in 20% of cases (12 eyes) and by 1.0D in 5% of cases (three eyes) (Fig. 1). In the group where the IOL power plan was changed (n = 15), the mean TBUT and CSS values were 3.0 ± 1.3 s and 1.1 ± 0.6 points, respectively. In contrast, these values in the group in which the IOL power plan was not changed (n = 45) were 4.0 ± 1.4 s and 0.6 ± 0.6 points, respectively. In IOL power change group, TBUT was significantly lower, and CSS was significantly higher compared to no change group (p = 0.023/0.013). There was no significant difference in ConSS and MGD stage between two groups (ConSS/MGD stage - IOL power change group: 0.9 ± 0.4 points/1.8 ± 0.4, no change group: 0.8 ± 0.5 points/1.8 ± 0.4, p = 0.638/0.865) (Fig. 2).

Comparative analysis of dry eye severity between the group in which the IOL power was changed and the group in which it was kept the same. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. *p < 0.05. IOL intraocular lens, TBUT tear film break-up time, CSS corneal staining score (SICCA score), ConSS conjunctival staining score (Oxford scheme), MGD meibomian gland dysfunction.

Upon comparing the preoperative refraction predicted from the ocular biometric measurements used for IOL power calculation with the refractive outcomes 1 month after surgery, the MAE showed no significant difference among all groups. The median absolute error (MedAE) was 0.47D in the mean K difference ≥ 0.25D group, and 0.34D in the mean K difference < 0.25D group. In the K1 difference ≥ 0.25D group, the MedAE was 0.33D, and 0.37D for group with K1 difference < 0.25D. The MedAE was 0.41D in the K2 difference ≥ 0.25D group, and 0.37D in the K2 difference < 0.25D group. However, cases of refractive surprise (> 0.5D) were observed in 45.5% of cases (five eyes) in the mean K difference ≥ 0.25D group, compared with 17.9% (five eyes) in the mean K difference < 0.25D group, with a significant p value of 0.037. Refractive surprise cases (> 0.5D) comprised 26.7% of cases (four eyes) in the K1 and K2 difference ≥ 0.25D group, and 22.2% of cases (six eyes) in the K1 and K2 difference < 0.25D group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.168). In addition, cases of refractive surprise (> 1.0D) were observed in two eyes in the mean K difference ≥ 0.25D group, with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.020) (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study evaluated the variability of ocular biometry before cataract surgery using the IOLMaster 700 and investigated the effects of DED on ocular biometric measurements. K values and the amount of corneal astigmatism showed a relatively higher variability between two repeated measurements compared with AL and ACD. The axis of corneal astigmatism was also variable. In 25% of cases, IOL power was changed from the initial surgical plan because of variability. Mean K difference ≥ 0.25D was significantly associated with lower preoperative TBUT, higher preoperative CSS, and postoperative refractive surprise (> 0.5D).

Accurate determination of AL and K values is essential for precise IOL power calculations. Deviations in refractive outcomes after cataract surgery primarily result from fluctuations in AL and anterior keratometry. Several methods, including optical low coherence reflectometry (OLCR), swept-source optical coherence tomography (ssOCT), and Scheimpflug technology, are currently employed for ocular biometric measurements. Despite the utilization of new devices such as the IOLMaster 700 (ssOCT) and the Lenstar LS 900 (OLCR), as well as modern IOL power calculation formulas including BUII, EVO, Hill-Radial Basis Function, Kane Formula, and Ladas Super Formula, the IOL power calculation is not entirely foolproof21. Older individuals have a higher prevalence of DED and are the main candidates for cataract surgery22,23. Of 120 preoperative cataract patients in the United States, 80% had at least one abnormal sign indicating ocular surface dysfunction24. Most patients scheduled for cataract surgery had DED, 62.9% had a TBUT of 5 s or less, and 77% had positive corneal staining25. Thus, it is important to know how preoperative DED affects the variability of ocular biometric measurements in patients with cataract.

The IOLMaster 700 has demonstrated higher reproducibility and measurement accuracy compared with other devices5,26,27. This device utilizes ssOCT and offers a measurement based on images, enabling the examiner to observe the entire longitudinal section of the eye. The IOLMaster 700 assesses AL through the mean values obtained from three scans along each of the six meridians5. In patients with posterior subcapsular cataracts, there are instances where the IOLMaster 500 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) and other ocular biometric devices have failed to acquire AL measurements28. The IOLMaster 700 demonstrated repeatability and reproducibility limits of ± 0.014 and ± 0.023 mm for AL, ± 0.26 and ± 0.27D for corneal power, and ± 0.02 and ± 0.02 mm for ACD29. However, despite the excellent repeatability and reproducibility observed with the IOLMaster 700, noticeable discrepancies were identified. Srivannaboon et al. demonstrated that keratometry measurements using the IOLMaster 700 showed slightly lower intraclass correlation coefficients compared to other parameters such as ACD, AL and lens thickness6. Another study reported reduced repeatability in astigmatism measurements with the IOLMaster 700, which may be attributed to the influence of tear film instability on corneal parameter measurements30. Lens opacity is known to affect the reliability of group refractive index based biometers such as the IOLMaster 700 31. De Bernardo et al. demonstrated that lens opacity can introduce systematic errors in AL measurements, proposing a correction factor to address this issue31. In addition, although this study did not use mydriatic eye drops before ocular biometric measurements, it is important to note that mydriatic eye drops can influence ACD32. However, mydriatic eye drops do not induce significant changes in choroidal thickness at the foveal area, ensuring reliable AL measurements33.

Previous studies have reported inaccuracies in AL measurements for patients with DED34. However, in our study, the IOLMaster 700 accurately measured AL, and the range of AL difference between the two measurements was almost negligible at 0–0.06 mm. In a study assessing the reliability of the IOLMaster 700, the repeatability of ocular biometric measurements, specifically WTW values, was found to be lower in patients with cataract compared with that in healthy children and adults35. The diminished repeatability of WTW values in this study is presumed to be associated with corneal arcus development in patients with cataract, possibly because of their advanced age36. In addition, the IOLMaster 700 utilizes ssOCT images for ACD and keratometric measurements, reducing measurement errors and failure rates5. The IOLMaster 700 and IOLMaster 500 both utilize the telecentric keratometry measurement method, projecting light onto the cornea to measure its curvature37. However, in this study, the differences in K values were larger, with the K1 difference averaging 0.21 ± 0.21D (max range 1.25D), the K2 difference averaging 0.21 ± 0.23D (max range 1.49D), and the mean K difference averaging 0.18 ± 0.17D (max range 0.88D) (Table 3). Unavoidable errors were revealed when the same patient underwent measurement twice by the IOLMaster700, separated by an interval of 17.1 ± 5.2 days. Our study demonstrated that despite the use of advanced instruments like the IOLMaster 700, inconsistencies in ocular biometric measurements may arise, particularly in patients with DED and especially in those with decreased TBUT or increased CSS.

Our findings demonstrated that mean K values, in particular, may contribute substantially to errors in IOL power. In addition, we demonstrated the influence of DED on this variability. In the high K variability group (mean K difference ≥ 0.25D), TBUT was significantly shorter at 3.1 ± 1.3 s, and CSS was higher at 1.1 ± 0.6 points (Table 4). This suggests that DED may influence ocular biometric measurements. These findings are consistent with previous studies. Hiraoka et al. assessed the precision of biometric measurements by conducting the procedure twice using the IOLMaster 500 within the same day34. The repeatability of both keratometry and AL measurements exhibited a negative correlation with TBUT34. A shorter TBUT was associated with decreased repeatability in both keratometry and AL measurements34. However, no such correlations were identified for abnormal corneal staining34. Furthermore, Epitropoulos et al. demonstrated that average K variability was significantly high in the hyperosmolar group (n = 50) compared with that in the normal group (n = 25)14. Teshigawara et al. also demonstrated that a 2% rebamipide ophthalmic suspension (Mucosta ophthalmic suspension UD2%; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) improved the tear film stability and significantly reduced intra-patient discrepancies in astigmatism power and axis measurements obtained through two repeated measurements using the IOLMaster 700, compared with the Mytear artificial tear ophthalmic solution (Mytear®; Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan)38. Some studies have reported the worsening of ocular surface condition owing to the instability of the tear film39,40. Shin et al. demonstrated that there was a negative correlation between the average NIBUT and the absolute differences observed in Kmax and astigmatism16. Thus, all these findings indicate that a stable tear film is essential for accurate measurements using the IOLMaster14. Astigmatic axis change was observed in two ocular biometric measurements with the IOLMaster 700. Accurately measuring the astigmatic axis is crucial for determining the angular orientation of toric IOLs. In this study, 31.3% (10 of 32) exhibited a difference of 10 degrees or more in the astigmatic axis, and among them, 9.4% (3 of 32) showed differences of 30 degrees or more. In a study by Matossian et al., 68% of patients showed a change in the astigmatism axis of orientation after treatment with a thermal pulsation system41. Toric IOLs are only implanted in patients with significant corneal astigmatism, and it is known that the repeatability of axis measurements improves with the higher amount of corneal astigmatism42. However, the instability of the tear film due to dry eye can cause variability in the astigmatism axis43,44. Therefore, the management of dry eye prior to cataract surgery can lead to successful outcomes in toric IOL implantation.

Although there were 5 cases of refractive surprise (> 0.5D) in both K variability groups, the rate in the group with mean K differences of 0.25D or more was significantly higher at 45.5% (p = 0.037). However, when dividing the groups based on K1 and K2, there was no significant difference in refractive surprise rates (Table 5). Kim et al. analyzed the 1-month postoperative MAE in two groups: one group without preoperative treatment and another group that received preoperative treatment starting 2 weeks before cataract surgery, including loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5%, cyclosporine A ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%, eyelid scrub, and warm compression45. In the group without preoperative treatment, refractive surprises occurred at a rate of 17.3% (n = 9) using the Sanders Retzlaff Kraff/Theoretical (SRK/T) formula and 15.4% (n = 8) using the BUII formula45. However, after preoperative treatment with topical steroid eye drops, the refractive surprises significantly decreased to 3.8% (n = 2) using the SRK/T formula and to 1.9% (n = 1) using the BUII formula, indicating a meaningful difference45. Furthermore, upon comparing the variability in mean K differences between the dry eye and non-dry eye control groups based on two measurements, the dry eye group exhibited significantly higher variation46. Some studies have reported a higher variability in mean K in hyperosmolar groups compared with that in normal groups, with a greater proportion showing IOL power differences of 0.5D or more14. Although there are studies suggesting the use of treatments like rebamipide47 and cyclosporine 0.09%48, 49 to reduce refractive errors, further research is required. However, it is necessary to recognize the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery clinical committee’s recommendation that adequate treatment for ocular surface disease before cataract or refractive surgery is essential as a matter of great importance49. Further research is warranted, including a comparative analysis of variability between the group undergoing preoperative DED management and the group without any intervention.

This study had some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small. Second, this study was a single-center study using a retrospective design. Third, the study only evaluated outcomes 1 month after surgery, providing a relatively short follow-up period. Fourth, device-assisted objective evaluation of DED, such as NIBUT or lipid layer thickness, was not conducted in this study. Fifth, the optimized A-constant for the ARTIS PL E and Vivinex XY1 IOLs was not applied. Sixth, the lack of preliminary sample size computation was a limitation of this study. However, our study showed that the IOLMaster 700, the latest ocular biometric device, exhibited notable measurement errors due to DED. These differences were clinically significant enough to impact cataract surgery planning and postoperative refractive outcomes. Further research is needed to investigate the specific parameters of DED affecting measurement variabilities and the optimal management strategy for preoperative dry eye before ocular biometry.

In conclusion, variability in mean K and the amount and axis of corneal astigmatism was more frequent compared to variability in AL and ACD when measured twice with the IOLMaster 700 before cataract surgery. Lower TBUT and higher CSS were significantly associated with increased variability in mean K values. Vigorous management of preoperative DED is crucial to obtain accurate K values in IOL power calculation.

Methods

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korea University Anam Hospital (IRB number: 2023AN0495) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived with the approval of the IRB of the Korea University Anam Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the medical records of 60 eyes in 60 patients who underwent ocular biometric measurements taken twice, with an interval of 17.1 ± 5.2 days, using the IOLMaster 700 before cataract surgery at a single tertiary institution (Anam Hospital of Korea University) from March to November 2023. All cataract surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (DH Kim) under topical anesthesia. If patients underwent cataract surgery of both eyes at the same time, right eye was included for analysis. Patients were excluded from enrollment if they met any of the following criteria: Sjogren’s syndrome, history of herpes keratitis or varicella zoster keratitis, history of Stevens–Johnson syndrome, blepharitis that required the use of topical antibiotics, keratoconus, or ocular graft-versus-host disease. Patients who underwent keratorefractive procedures (e.g., laser in situ keratomileusis, laser epithelial keratomileusis, photorefractive keratectomy), who had been diagnosed with corneal opacity, neurological or ophthalmologic diseases excluding cataract, and who had previous ocular surgery or ocular trauma were also excluded.

Ocular biometric measurements were performed without the use of mydriatic eye drops32. Intraocular pressure was not measured using applanation tonometer before biometry to avoid potential impact on corneal parameters50. All ocular biometric measurements in this study were performed by a single investigator. Ocular biometric measurements included AL, corneal refractive power (K values), ACD, horizontal corneal diameter (WTW) and astigmatism amount. Measurements of the astigmatism axis were included in the analysis only when the astigmatism amount exceeded 0.75D. The astigmatism axis values provided by the IOLMaster 700, ranging from 0 degrees to 180 degrees, were converted to facilitate the calculation of astigmatism axis errors. K values were analyzed by dividing it into flat K (K1), steep K (K2), and mean corneal anterior surface keratometry (mean K), which is the average value of K1 and K2. To analyze the variability in ocular biometric measurements, we calculated the average, standard error, and absolute differences between the first and second measurements. Furthermore, we compared the absolute differences of ocular biometric measurements taken twice, specifically focusing on cases where the absolute difference was equal to or greater than 0.25D. We investigated whether age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, MGD stage, and signs of DED influenced the measurement errors.

Dry eye examinations were performed on the same day as the first ocular biometric measurement. TBUT, ConSS (Oxford scheme, 0–5), and CSS (SICCA score, 0–6) were measured as parameters of DED17,18,19. TBUT was assessed over a 10-second duration using a stopwatch; the measurement was conducted following the administration of 2 µL of a 1% preservative-free sodium fluorescein solution into the lower conjunctival sac using a micropipette. The corneal fluorescein staining pattern was assessed using the SICCA score. All patients were examined at the slit lamp using the yellow filter.

The postoperative spherical equivalent refraction, measured 1 month after the surgery, was compared with the preoperative refraction predicted from the ocular biometric measurements used for IOL power calculation. Postoperative spherical equivalent refraction was measured using RK-F2 Full Auto Ref-Keratometer (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). The data were obtained from follow-up visits recorded in the medical records at least 1 month after the surgery. Using the BUII formula, we calculated the expected refractive power of the IOL. This comparison allowed us to determine the prediction error of the IOL. As the error could manifest as positive or negative values, we calculated the absolute prediction error to prevent mathematical discrepancies. An aspheric one-piece monofocal IOL, including the ARTIS PL E (Cristalens Industrie, Lannion, France) and Vivinex XY1 (Hoya, Tokyo, Japan), was implanted in all surgeries. In calculating the IOL power using the BUII formula, the manufacturer’s A-constant of 119.3 (ARTIS PL E) and 118.9 (Vivinex XY1) was applied. Target refraction for IOL power calculation was emmetropia. Cases in which complications such as posterior capsular rupture or severe zonular weakness occurred during surgery were excluded from the analysis. Cases with MAE > 0.5D were defined as a refractive surprise in this study. In cases where the predicted postoperative refraction, as calculated using the BUII formula, exceeded − 0.5D, we considered changing to an alternative IOL power to minimize refractive surprise. In the preoperative planning for cataract surgery, we additionally compared the rates of cases where IOL power corresponding to the target refractive value remained the same and cases where it was altered after two measurements. Moreover, TBUT, CSS, ConSS, and MGD stage were compared between the group in which the IOL power was changed and the group in which it was kept the same.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate normality. A paired t-test was used to compare differences in means. Reproducibility of measurements was evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to calculate the within-subject standard deviation (Sw)51. The reproducibility limit, which represents the likely limits that 95% of measurements should be within, was calculated as 1.96√2 x Sw51. We divided the groups based on mean K difference, specifically into those with a difference < 0.25D and those with a difference ≥ 0.25D. We employed an unpaired t-test to analyze the factors influencing these groups. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test, and categorical variables were examined using the chi-square test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The raw data used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Wang, W., Yan, W., Müller, A. & He, M. A global view on output and outcomes of cataract surgery with national indices of socioeconomic development. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, 3669–3676. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.17-21489 (2017).

Davis, G. The evolution of cataract surgery. Mo. Med. 113, 58–62 (2016).

Olsen, T. Calculation of intraocular lens power: A review. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 85, 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00879.x (2007).

Cione, F. et al. A no-history multi-formula approach to improve the IOL power calculation after laser refractive surgery: Preliminary results. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082890 (2023).

Akman, A., Asena, L. & Güngör, S. G. Evaluation and comparison of the new swept source OCT-based IOLMaster 700 with the IOLMaster 500. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 100, 1201–1205. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307779 (2015).

Srivannaboon, S., Chirapapaisan, C., Chonpimai, P. & Loket, S. Clinical comparison of a new swept-source optical coherence tomography–based optical biometer and a time-domain optical coherence tomography–based optical biometer. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 41, 2224–2232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.03.019 (2015).

Ferrer-Blasco, T. et al. Evaluation of the repeatability of a swept-source ocular biometer for measuring ocular biometric parameters. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. 255, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-016-3555-z (2017).

Savini, G., Hoffer, K. J., Balducci, N., Barboni, P. & Schiano-Lomoriello, D. Comparison of formula accuracy for intraocular lens power calculation based on measurements by a swept-source optical coherence tomography optical biometer. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 46, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.08.044 (2020).

Hipólito-Fernandes, D. et al. Anterior chamber depth, lens thickness and intraocular lens calculation formula accuracy: Nine formulas comparison. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 106, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317822 (2022).

Cooke, D. L. & Cooke, T. L. Comparison of 9 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 42, 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.06.029 (2016).

Carmona-González, D., Castillo-Gómez, A., Palomino-Bautista, C. & Romero-Domínguez, M. Gutiérrez-Moreno, M. Á. Comparison of the accuracy of 11 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 31, 2370–2376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120962030 (2021).

Melles, R. B., Holladay, J. T. & Chang, W. J. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology. 125, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.027 (2018).

Kane, J. X., Van Heerden, A., Atik, A. & Petsoglou, C. Intraocular lens power formula accuracy: Comparison of 7 formulas. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 42, 1490–1500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.07.021 (2016).

Epitropoulos, A. T., Matossian, C., Berdy, G. J., Malhotra, R. P. & Potvin, R. Effect of tear osmolarity on repeatability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 41, 1672–1677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.01.016 (2015).

Montés-Micó, R. Role of the tear film in the optical quality of the human eye. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 33, 1631–1635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.06.019 (2007).

Shin, H., Jung, S. & Jung, J. W. Effects of non-invasive keratograph break-up time on the repeatability of keratometry measurements. J. Korean Ophthalmological Soc. 64, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2023.64.2.99 (2023).

Whitcher, J. P. et al. A simplified quantitative method for assessing keratoconjunctivitis sicca from the Sjögren’s Syndrome International Registry. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 149, 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2009.09.013 (2010).

Bron, A. J., Evans, V. E. & Smith, J. A. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 22, 640–650. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008 (2003).

Rasmussen, A. et al. Comparison of the American-European Consensus Group Sjögren’s syndrome classification criteria to newly proposed American College of Rheumatology criteria in a large, carefully characterised sicca cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203845 (2014).

Chylack, L. T. et al. The lens opacities classification system III. Arch. Ophthalmol. 111, 831–836. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060119035 (1993).

Moshirfar, M. et al. Comparing the accuracy of the Kane, Barrett Universal II, Hill-Radial basis function, Emmetropia Verifying Optical, and Ladas Super Formula intraocular lens power calculation formulas. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 2643–2652. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S417865 (2023).

Graae Jensen, P. et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease among individuals scheduled for cataract surgery in a Norwegian cataract clinic. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S407805 (2023).

Noor, N. A., Rahayu, T. & Gondhowiardjo, T. D. Prevalence of dry eye and its subtypes in an elderly population with cataracts in Indonesia. Clin. Ophthalmol. 14, 2143–2150. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S240057 (2020).

Gupta, P. K., Drinkwater, O. J., VanDusen, K. W., Brissette, A. R. & Starr, C. E. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 44, 1090–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.06.026 (2018).

Trattler, W. B. et al. The prospective health assessment of cataract patients’ ocular surface (PHACO) study: The effect of dry eye. Clin. Ophthalmol. 11, 1423–1430. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S120159 (2017).

Arriola-Villalobos, P. et al. Agreement and clinical comparison between a new swept-source optical coherence tomography-based optical biometer and an optical low-coherence reflectometry biometer. Eye. 31, 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.241 (2017).

Kurian, M. et al. Biometry with a new swept-source optical coherence tomography biometer: Repeatability and agreement with an optical low-coherence reflectometry device. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 42, 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.01.038 (2016).

Freeman, G. & Pesudovs, K. The impact of cataract severity on measurement acquisition with the IOLMaster. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 83, 439–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00473.x (2005).

Bullimore, M. A., Slade, S., Yoo, P. & Otani, T. An evaluation of the IOLMaster 700. Eye Contact Lens. 45, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICL.0000000000000552 (2019).

Sharma, A. & Batra, A. Assessment of precision of astigmatism measurements taken by a swept-source optical coherence tomography biometer-IOLMaster 700. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69, 1760–1765. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2776_20 (2021).

De Bernardo, M., Cione, F., Capasso, L., Coppola, A. & Rosa, N. A formula to improve the reliability of optical axial length measurement in IOL power calculation. Sci. Rep. 12, 18845. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23665-0 (2022).

Tasci, Y. Y., Yesilirmak, N., Yuzbasioglu, S., Ozdas, D. & Temel, B. Comparison of effects of mydriatic drops (1% cyclopentolate and 0.5% tropicamide) on anterior segment parameters. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69, 1802–1807. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2677_20 (2021).

Gioia, M. et al. Evaluation of tropicamide–phenylephrine mydriatic eye drop instillation on choroidal thickness. J. Clin. Med. 12, 6355. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196355 (2023).

Hiraoka, T. et al. Influence of dry eye disease on the measurement repeatability of corneal curvature radius and axial length in patients with cataract. J. Clin. Med. 11, 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030710 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Reliability of a new swept-source optical coherence tomography biometer in healthy children, adults, and cataract patients. J. Ophthalmol. 2020(8946364). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8946364 (2020).

Raj, K. M., Reddy, P. A. S. & Kumar, V. C. Significance of corneal arcus. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 7, S14–S15. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-7406.155765 (2015).

Karunaratne, N. Comparison of the Pentacam equivalent keratometry reading and IOL Master keratometry measurement in intraocular lens power calculations. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 41, 825–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.12124 (2013).

Teshigawara, T., Meguro, A. & Mizuki, N. Effects of rebamipide on differences in power and axis of corneal astigmatism between two intra-patient keratometric measurements in dry eyes. Ophthalmol. Therapy. 10, 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-021-00368-9 (2021).

Koh, S. et al. Effects of suppression of blinking on quality of vision in borderline cases of evaporative dry eye. Cornea. 27, 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815be9c8 (2008).

Koh, S. et al. Simultaneous measurement of tear film dynamics using wavefront sensor and optical coherence tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 3441–3448. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.09-4430 (2010).

Matossian, C. Impact of thermal pulsation treatment on astigmatism management and outcomes in meibomian gland dysfunction patients undergoing cataract surgery. Clin. Ophthalmol. 14, 2283–2289. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S263046 (2020).

Feng, Y., Nitter, T., Bertelsen, G. & Stojanovic, A. Repeatability and agreement of total corneal astigmatism measured in keratoconic eyes using four current devices. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.14423 (2024).

Holladay, J. Accurate corneal power measurements for IOL calculations. Ocul. Surg. News US Ed. (2016). https://www.healio.com/news/ophthalmology/20160823/accurate-corneal-power-measurements-for-iol-calculations

Matossian, C. Everything you thought you knew about astigmatism and dry eye is wrong. Ophthalmol. Times (2019). https://www.ophthalmologytimes.com/view/everything-you-thought-you-knew-about-astigmatism-and-dry-eye-wrong

Kim, J., Kim, M. K., Ha, Y., Paik, H. J. & Kim, D. H. Improved accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation by preoperative management of dry eye disease. BMC Ophthalmol. 21, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-021-02129-5 (2021).

Yang, F., Yang, L., Ning, X., Liu, J. & Wang, J. Effect of dry eye on the reliability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 47, 103999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfo.2023.04.016 (2023).

Teshigawara, T., Meguro, A. & Mizuki, N. The effect of rebamipide on refractive accuracy of cataract surgery in patients with dry eye. Ophthalmol. Therapy. 11, 603–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-022-00457-3 (2022).

Hovanesian, J. A., Berdy, G. J., Epitropoulos, A. & Holladay, J. T. Effect of cyclosporine 0.09% treatment on accuracy of preoperative biometry and higher order aberrations in dry eye patients undergoing cataract surgery. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, 3679–3686. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S325659 (2021).

Starr, C. E. et al. An algorithm for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment of ocular surface disorders. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 45, 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.03.023 (2019).

De Bernardo, M. et al. Comparison between dynamic contour tonometry and Goldmann applanation tonometry correcting equations. Sci. Rep. 12, 20190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24318-y (2022).

McAlinden, C., Khadka, J. & Pesudovs, K. Precision (repeatability and reproducibility) studies and sample-size calculation. J. Cataract Refractive Surg. 41, 2598–2604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.06.029 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for the English language editing.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00243720) and a grant from Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea (K2319651 and K2225511).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.A. and D.H.K. were involved in the conception and design of the study. S.H.A. and D.H.K. were involved in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. S.H.A. was involved in the writing of the first draft of the manuscript. D.H.K. was involved in the acquisition of funding. Y.E., J.S.S., and D.H.K. were involved in the manuscript review, statistical analysis, and discussion of the data. Y.E., J.S.S., and D.H.K. were involved in supervision. All authors were involved in final approval of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahn, S., Eom, Y., Song, J.S. et al. Short-term variability in ocular biometry and the impact of preoperative dry eye. Sci Rep 14, 26762 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77572-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77572-7

This article is cited by

-

To evaluate the effects of artificial tears on ocular biological parameters in dry eye and non-dry eye patients

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Evidenzbasierter Einsatz von Sonderlinsen: Management von postoperativer Unzufriedenheit

Die Ophthalmologie (2025)