Abstract

Sports injuries often arise from improper scheduling of exercise loads, and timely assessment of these loads is essential for minimizing injury risk. This article investigates the validity of using changes in pupillary light reflex (PLR) during dynamic aerobic training as a novel approach to evaluating exercise load. Dynamic aerobic training was conducted on a power bicycle for 15 min. With a 3-minute interval as the demarcation line, PLR measurement was performed before training and heart rate was recorded throughout the process. The Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale invented by Borg was used for scoring before training and after training. The normal distribution of data was confirmed through the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pearson correlation analysis was used to quantify the correlation between variables. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) analysis were used to determine the indicators of exercise load. The optimal threshold of the indicators was calculated through the Youden index to evaluate sensitivity and specificity. Thirty male second-tier athletes with a mean age of 23.66 ± 2.21 years, a mean height of 175.3 ± 6.5 cm, and a mean weight of 68.99 ± 10.35 kg participated in this study. Based on the RPE scale results, it was confirmed that the 15-minute dynamic aerobic exercise successfully elicited varying levels of perceived exertion among the athletes. The findings of this study indicate significant changes in PLR and heart rate (HR) with increasing exercise duration and external load. There were strong correlations between RPE and maximum constriction velocity (MCV) (|r| = 0.8309, p < 0.001, negative correlation), maximum diameter (INIT) (r = 0.7641, p < 0.001, positive correlation), time to reach 75% recovery (T75) (|r| = 0.7289, p < 0.001, negative correlation), and HR (r = 0.8170, p < 0.001, positive correlation). Additionally, the results suggest that MCV is the most significant potential indicator for detecting internal load, exhibiting high specificity and sensitivity (AUC = 0.8509, p < 0.001). Further analysis using the Youden index identified 5.07 mm/s as the optimal cutoff value for MCV, indicating that when MCV ≤ 5.07 mm/s, the athletes’ internal load has reached an “Intense” state. PLR may be a potential indicator for assessing internal load Further investigation could involve developing a non-invasive exercise load detection system based on pupillary variable indicators, providing a valuable new approach for accurately measuring exercise load.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sports injuries have become a critical factor affecting athletic performance1,2,3,4. These injuries can cause physical issues such as pain, swelling, and restricted movement, with severe cases potentially leading to long-term physical dysfunction or even disability. Additionally, sports injuries can impact athletes’ mental health, increasing the risk of anxiety and depression5,6,7. Most training-related injuries are due to improper management of exercise load, and scientific monitoring of exercise load can help prevent these injuries8,9. Improper management of exercise load is typically defined as sudden increases in training volume, overtraining, and insufficient recovery, all of which can lead to sports injuries10,11. Exercise load can be divided into internal and external loads12. External load refers to the objective measures of exercise, such as the amount, intensity, and frequency of activity performed by athletes during training or competition13. Internal load, on the other hand, refers to the physiological and psychological responses of the athlete’s body to the exercise stimuli during training or competition, and serves as a critical indicator of the athlete’s gradual adaptation to the external load14,15.

Current instruments can reliably quantify external load; however, research indicates that individual differences result in varying internal load for each athlete when exposed to the same external load16. In many studies, methods for assessing internal load typically include heart rate (HR), electromyography (EMG), blood lactate (LAC), blood pressure (BP), maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max), and the ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) scale17,18. However, due to cumbersome procedures and invasive blood sampling, these methods have significant limitations in practical applications. In contrast, pupillary indicators, as an objective physiological measure, offer a highly valuable method for detecting exercise intensity19,20,21,22. Previous studies have explored changes in pupil diameter during exercise, finding that pupil diameter expands with increasing exercise load20,23,24. However, these studies employed eye-tracking systems using infrared light to measure changes in pupil diameter, which not only limit the detection parameters but are also influenced by light reflection, gaze position, and pupil dilation latency, thereby affecting the accuracy of the data. Furthermore, the data obtained from these methods often require computational processing or conversion before being used to assess exercise load practically.

Pupillary light reflex (PLR) is an effective indicator reflecting pupil changes and has been applied in various contexts25. Quantitative pupillometry can provide multiple accurate and reliable indicators, such as pupil diameter and maximum constriction velocity, which hold potential application value26,27,28,29. To date, no studies have analyzed the relationship between PLR changes and exercise load.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of PLR in detecting exercise load during dynamic aerobic training, aiming to explore a novel non-invasive, reliable, and convenient method for assessing athletes’ exercise load. This approach facilitates the timely adjustment of athletes’ training status to prevent sports injuries. We hypothesize that changes in PLR are correlated with exercise load, and that internal load can be accurately assessed by quantifying relevant indicators of PLR.

Methods

Participants

Thirty male second-tier athletes from the Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, Beijing, China participated in this study. Inclusion criteria for subjects were: (1) male athletes; (2) physically healthy with normal blood pressure. Exclusion criteria were: (1) individuals with chronic health issues or physical disabilities affecting their ability to perform physical fitness tests; (2) those who underwent major surgery or suffered serious injury within the past six months; (3) inability to provide written informed consent; (4) safety concerns regarding participation in physical fitness testing or medical advice against participation. All subjects adhered to the following requirements before the experiment: (1) fasting from food and water for 2 h prior to training; (2) abstaining from high-intensity exercise within the past 24 h; (3) at rest, RPE < 9, HR < 90 bpm. This study was approved by the Scientific Research Review Committee of the Capital University of Physical Education and Sports (Approval No: 2024A001), and all subjects provided written informed consent. The study design adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

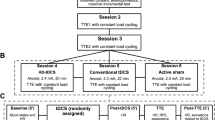

Procedure

Cognitive processes and light intensity are critical factors influencing pupil changes. To minimize potential interference with pupil changes, this study required all athletes to rest for 2 min upon arrival at the fitness center. Subsequently, within 2 min, they were instructed to perform arithmetic calculations by subtracting 7 or 13 consecutively from either 100 or 1000, with the sequence randomly assigned at the start of each arithmetic session. Athletes provided oral responses, and experimenters verified the accuracy of their answers20. To ensure that all athletes started the study at the same functional level, RPE and HR data were collected after a 3-minute rest following the mental arithmetic phase. When the athletes’ RPE was less than 9 and HR was below 90 bpm, they began incremental load dynamic aerobic training using the IREB1901M6 power bike (IronMan, Jiangsu Province, China). The total training duration was 15 min, with all athletes maintaining a cycling cadence of 60–70 RPM throughout the session to ensure stability and controllability. The training process gradually increased the load as follows: Stage 1 (0–3 min): The initial load was set at 10% of the power bike’s maximum load; Stage 2 (3–6 min): Increased to 20% of the maximum load; Stage 3 (6–9 min): Increased to 30% of the maximum load; Stage 4 (9–12 min): Increased to 40% of the maximum load; Stage 5 (12–15 min): Increased to 50% of the maximum load. After the 15 min of dynamic aerobic training, the athletes sat on the power bike for recovery. All experiments were conducted under consistent environmental conditions (temperature: 24 °C, humidity: 65%, light intensity: 300 lx).

PLR data collection

The PLR-3000 pupillometer (NeurOptics, CA, USA) was used to measure pupillary light reflex (PLR). This device employs a rubber cup to cover the eye being measured while the subject uses their hand to cover the non-measured eye. A visible white light pulse of 120µW intensity is applied for 0.8s to elicit the pupillary reflex. Video images are captured at a rate of 30 frames per second for 3.21s30. The device measures eight pupillary parameters: Maximum Diameter (INIT), Minimum Diameter (END), Constriction Ratio (INIT-END / INIT, δ), Latency of constriction (LAT), Average constriction velocity (ACV), Maximum constriction velocity (MCV), Average dilation velocity (ADV), and Time to reach 75% recovery (T75). Quantitative measurements include a minimum resolution of 0.1 mm for pupil diameter, 0.01s for time-related measurements, 0.01 mm/s for constriction and dilation velocities, and 1% for the pupillary constriction ratio.

Pupil measurements of the right eye were conducted on athletes at six time points: before dynamic aerobic training, and at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 min into the training session. Data for each participant were recorded accordingly. During testing, athletes underwent 10 s of dark adaptation followed by 10 s of light adaptation, with their left eye tightly closed and covered by their left hand. During formal testing, athletes were instructed to keep their right eye open without blinking for as long as possible. Instances of blinking or shifting gaze away from the testing apparatus were considered invalid pupil data. In case of interruption, a rest period of 3–5 s was allowed before repeating the test.

RPE data collection

The Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale, developed by Borg, is a subjective method used to assess internal load, commonly employed to monitor training load and fatigue levels31. This scale consists of numerical or descriptive ratings, enabling athletes to evaluate their internal load based on their subjective perceptions32,33,34,35. In this study, RPE was recorded twice for each athlete: before dynamic aerobic training and immediately after 15 min of exercise. Scores obtained immediately after training were categorized based on RPE rating criteria into two levels: “Calm” (RPE ≤ 14) and “Intense” (15 ≤ RPE ≤ 20)31,36,37.

HR data collection

HR data from the participants were collected using the V800 smart heart rate monitor (Polar, Oulu, Finland), which continuously monitored their heart rates from the start of training until the completion of the 15-minute dynamic aerobic session.

Statistical analysis

Data processing was performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics 26.0, IBM, Armonk, U.S.) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism 9.0, GraphPad Software, Boston, U.S.). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether the data followed a normal distribution. In this study, changes in PLR and HR were described using the Mean ± SD format. Subsequently, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to quantify the relationships between PLR, HR, and RPE at the 15-minute mark, where PLR and HR served as dependent variables and RPE as the independent variable. For clarity, a relative standard for correlation strength was adopted: weak correlation (r < 0.4), moderate correlation (0.4 ≤ r < 0.7), and strong correlation (r ≥ 0.7)38. ROC curves and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) were utilized to identify the optimal indicators for assessing internal load after the 15-minute dynamic aerobic training. In this step, the dependent variable was the RPE level categorization, while the independent variables were PLR and HR. To further determine the optimal cutoff values for each indicator, the Youden index was employed, calculated as Youden index = Sensitivity + (1 - Specificity), to maximize the difference between the model’s sensitivity and specificity, thus obtaining the best classification point. This approach enables the evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of the sample results, ensuring the scientific rigor and accuracy of the experimental findings.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Scientific Research Review Committee of the Capital University of Physical Education and Sports (Approval number: 2024A001), and all subjects provided written informed consent. The study design adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Results

Variations of PLR and HR

There were no statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the subjects (Table 1). Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of PLR indices and HR. The results indicate that with the increase in exercise duration and external load, the PLR metrics of INIT, END, δ, LAT, and ADV significantly increased. Conversely, ACV, MCV, and T75 showed a significant decrease. Additionally, HR significantly increased in response to the prolonged duration of exercise and the elevated external load. Plotting the above data allows for a more intuitive observation: INIT, END, δ, LAT, ADV, and HR show increasing trends with exercise duration and external load (Fig. 1A, B, C, D, G, I), whereas ACV, MCV, and T75 exhibit decreasing trends (Fig. 1E, F, H).

Results of the RPE levels

To assess the appropriateness of exercise load, we evaluated athletes’ RPE scores, which significantly increased after training compared to before. Additionally, this study categorized the scale into two levels: “Calm” (RPE ≤ 14) and “Intense” (15 ≤ RPE ≤ 20). The results revealed that 7 athletes reported RPE scores ≤ 14, while 23 athletes reported scores between 15 and 20. The study indicates that after 15 min of dynamic aerobic training, 7 out of 30 athletes perceived the exercise intensity as “Calm” and 23 perceived it as “Intense” (Table 3).

Correlation analysis between variations of PLR and HR and results of the RPE levels

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant associations between INIT (r = 0.7641, p < 0.001), MCV (|r| = 0.8309, p < 0.001), T75 (|r| = 0.7289, p < 0.001), and HR (r = 0.8170, p < 0.001) with RPE (Fig. 2A, F, H, I). END showed a moderate correlation with RPE (r = 0.6308, p < 0.001), as did ACV (|r| = 0.6832, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B, E). Conversely, LAT (r = 0.2691, p > 0.1), ADV (r = 0.2304, p > 0.1), and δ (r = 0.1697, p > 0.1) exhibited weak correlations with RPE (Fig. 2D, G, C).

Analysis of the effectiveness of PLR and HR in detecting Exercise load in athletes

ROC curve analysis demonstrated significant predictive value of PLR and HR changes for assessing internal load among athletes (Table 4). In this study, analysis was focused only on the variables showing the highest correlations (INIT, MCV, T75, and HR). Based on the area under the ROC curve (AUC = 0.8509, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3), MCV was identified as an effective indicator for evaluating internal load. Further determination using the Youden index established a critical value of 5.07 mm/s for MCV in detecting internal load, with a sensitivity of 85.71% and specificity of 78.26%.

Discussion

This study explored the effectiveness of changes in PLR and HR for detecting exercise load in athletes. The findings indicate that: (1) with increasing exercise duration and external load, INIT, END, ADV, LAT, δ, and HR significantly increased, while MCV, ACV, and T75 significantly decreased; (2) there was a significant correlation between changes in PLR and HR with changes in RPE after 15 min of aerobic training; (3) the variation in PLR showed high accuracy for assessing the internal load of athletes; (4) based on the area under the ROC curve and calculations using the Youden index, an MCV ≤ 5.07 mm/s indicates that the athletes’ perceived internal load has reached an “Intense” state. In our research, dynamic aerobic training with different exercise loads was conducted using a power bicycle to induce different exercise sensations. Previous literature indicates that the RPE is a subjective method for evaluating internal load and is typically used to monitor exercise load and fatigue degree32,33,34,35. Therefore, in this study, two RPE tests were performed before and after training to assess the subjective exercise sensations of athletes. Based on the increase in RPE scores of athletes after training, it can be inferred that the 15-minute dynamic aerobic training successfully induced different exercise sensations in athletes.

In this study, HR gradually increased with the extension of exercise duration and external load, which aligns with findings from earlier research39. This phenomenon may be attributed to a decrease in vagal tone and heightened sympathetic activity, along with several other factors, such as the peripheral muscles’ demand for increased blood supply40. Simultaneously, as exercise load continues to rise, the sympathetic nervous system becomes more active, releasing hormones such as adrenaline, which enhance cardiac contractility and increase HR, while promoting muscle blood flow. Additionally, the parasympathetic nervous system’s inhibitory effect on the heart diminishes, further contributing to the increase in HR41,42.

One of the most significant findings of this study is the notable changes in PLR with the increasing duration of exercise and external load. In our research, all athletes experienced the same external load during training, and the changes in PLR after training were associated with internal load. During exercise, as the external load continued to rise, sympathetic nervous system activity was enhanced, leading to an increase in both INIT and END. This finding aligns with studies by Hayashi23 and Kuwamizu24, who used HR and maximal oxygen uptake as markers of exercise intensity and found a correlation between pupil dilation trends from rest to maximal intensity and increases in HR and maximal oxygen uptake. Pupil diameter is regulated by both sympathetic dilation and parasympathetic constriction pathways; dilation muscle contraction pulls the iris outward, enlarging pupil diameter, while constriction muscle contraction relaxes the dilator, decreasing pupil diameter43,44,45. Adjusting pupil diameter to modulate the amount of light entering the eye plays a crucial role in visual acuity, which is essential in accurately identifying targets, objects, and distances—a critical component in sports performance46,47. The study also observed an increasing trend in δ, corroborating findings from Steinhauer48 that pupil dilation may involve exercise intensity’s impact on δ.

However, ACV and MCV decreased with the increasing duration of exercise and external load, a trend that aligns with the findings of Kaltsatou49. This change may be attributed to the impact of fatigue on nerve conduction velocity during exercise50. Previous studies have shown that T75 tends to increase with the difficulty of cognitive tasks51,52; however, in this study, T75 exhibited a downward trend. This phenomenon may be due to the use of two different intervention methods.By analyzing the experimental results, we found a high correlation between the changes in INIT, MCV, T75, and HR with RPE. Consequently, we performed ROC curve analysis on these four highly correlated indicators. The analysis revealed that the change in MCV achieved the highest AUC in detecting exercise intensity, indicating good sensitivity and specificity. This suggests that the range of MCV changes may serve as a potential indicator for internal load assessment in the future. Further clarification using the Youden index showed that when MCV ≤ 5.07 mm/s, it can be determined that the internal load has reached a state of “Intense” perception.

This study also has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small, including only 30 male secondary-level athletes and excluding female athletes, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Secondly, this study had limitations in the duration and external load set during dynamic aerobic training, leaving the results under longer durations and higher external loads still unknown. Thirdly, considering individual variations among athletes, the optimal threshold values for PLR indicators should be further validated through large-scale randomized controlled trials in the future.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of quantitative pupillometry in assessing the intensity of dynamic aerobic training among athletes. The results indicate that PLR may serve as a potential indicator for detecting exercise load. Further exploration could involve the development of a non-invasive exercise load detection system based on pupillary variables, offering a valuable new approach to accurately assess exercise load.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACV:

-

Average Constriction Velocity

- ADV:

-

Average Dilation Velocity

- AUC:

-

Area Under the Curve

- END:

-

Minimum Diameter

- HR:

-

Heart Rate

- INIT:

-

Maximum Diameter

- LAT:

-

Latency of Constriction

- MCV:

-

Maximum Constriction Velocity

- PLR:

-

Pupillary LightReflex

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- RPE:

-

Ratings of Perceived Exertion

- T75:

-

Time to reach 75% recovery

- δ:

-

Constriction Ratio (INIT-END/INIT)

References

Drew, M. K., Raysmith, B. P. & Charlton, P. C. Injuries impair the chance of successful performance by sportspeople: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 51 (16), 1209–1214. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096731 (2017).

Bahr, R. & Krosshaug, T. Understanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 39 (6), 324–329. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.018341 (2005).

Hägglund, M., Waldén, M. & Ekstrand, J. Risk factors for lower extremity muscle injury in professional soccer: the UEFA Injury Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 41 (2), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546512470634 (2013).

Engebretsen, A. H., Myklebust, G., Holme, I., Engebretsen, L. & Bahr, R. Intrinsic risk factors for acute ankle injuries among male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 20 (3), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00971.x (2010).

Fong, D. T., Hong, Y., Chan, L. K., Yung, P. S. & Chan, K. M. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 37 (1), 73–94. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737010-00006 (2007).

Physical therapies in. Sport and exercise[M] (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2007).

Hootman, J. M., Dick, R. & Agel, J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J. Athl Train. 42 (2), 311–319 (2007).

Hreljac, A. Impact and overuse injuries in runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36 (5), 845–849. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000126803.66636.dd (2004).

Bahr, R. & Holme, I. Risk factors for sports injuries–a methodological approach. Br. J. Sports Med. 37 (5), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.37.5.384 (2003).

Kuipers, H. & Keizer, H. A. Overtraining in elite athletes. Review and directions for the future. Sports Med. 6 (2), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198806020-00003 (1988).

Carder, S. L. et al. The Concept of Sport Sampling Versus Sport specialization: preventing Youth Athlete Injury: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 48 (11), 2850–2857. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546519899380 (2020).

Impellizzeri, F. M., Marcora, S. M., Rampinini, E., Mognoni, P. & Sassi, A. Correlations between physiological variables and performance in high level cross country off road cyclists. Br. J. Sports Med. 39 (10), 747–751. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.017236 (2005).

Abt, G. & Lovell, R. The use of individualized speed and intensity thresholds for determining the distance run at high-intensity in professional soccer. J. Sports Sci. 27 (9), 893–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410902998239 (2009).

Foster, C. et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J. Strength. Cond Res. 15 (1), 109–115 (2001).

Soligard, T. et al. How much is too much? (part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 50 (17), 1030–1041. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096581 (2016).

Sun, P. & Zhang, T. A. An empirical study on the evaluation of internal training load of football players during training and competition using the subjective fatigue scale: a case study of the Chinese men’s U21 selection team. Chin. Sports Sci. Technol. 58 (10), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.16470/j.csst.2021019 (2022).

Jamnick, N. A., Pettitt, R. W., Granata, C., Pyne, D. B. & Bishop, D. J. An examination and critique of current methods to Determine Exercise Intensity. Sports Med. 50 (10), 1729–1756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01322-8 (2020).

Mann, T., Lamberts, R. P. & Lambert, M. I. Methods of prescribing relative exercise intensity: physiological and practical considerations. Sports Med. 43 (7), 613–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0045-x (2013).

Zénon, A., Sidibé, M. & Olivier, E. Pupil size variations correlate with physical effort perception. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00286 (2014). Published 2014 Aug 25.

Hayashi, N., Someya, N. & Fukuba, Y. Effect of intensity of dynamic exercise on pupil diameter in humans. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 29 (3), 119–122. https://doi.org/10.2114/jpa2.29.119 (2010).

Wang, C. A. & Munoz, D. P. A circuit for pupil orienting responses: implications for cognitive modulation of pupil size. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 33, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2015.03.018 (2015).

Ferree, C. E. & Rand, G. Relation of size of pupil to intensity of light and speed of vision, and other studies. J. Exp. Psychol. 15 (1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0073631 (1932).

Hayashi, N. & Someya, N. Muscle metaboreflex activation by static exercise dilates pupil in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111 (6), 1217–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1716-z (2011).

Kuwamizu, R. et al. Pupil-linked arousal with very light exercise: pattern of pupil dilation during graded exercise. J. Physiol. Sci. 72 (1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12576-022-00849-x (2022). Published 2022 Sep 24.

Oddo, M. et al. Quantitative versus standard pupillary light reflex for early prognostication in comatose cardiac arrest patients: an international prospective multicenter double-blinded study. Intensive Care Med. 44 (12), 2102–2111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5448-6 (2018).

Zhao, W. et al. Inter-device reliability of the NPi-100 pupillometer. J. Clin. Neurosci. 33, 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2016.01.039 (2016).

Olson, D. M. et al. Interrater reliability of Pupillary assessments. Neurocrit. Care 24(2), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-015-0182-1 (2016).

Meeker, M. et al. Pupil examination: validity and clinical utility of an automated pupillometer. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 37 (1), 34–40 (2005).

Morelli, P., Oddo, M. & Ben-Hamouda, N. Role of automated pupillometry in critically ill patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 85 (9), 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.19.13437-2 (2019).

Shi, L. et al. Assessment of Combination of Automated Pupillometry and Heart Rate Variability to detect driving fatigue. Front. Public. Health. 10, 828428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.828428 (2022). Published 2022 Feb 21.

Borg, G. in Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales (ed. Borg, G.) 104 (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1998).

Borg, G. A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14 (5), 377–381 (1982).

Pereira, G. et al. Evolution of perceived exertion concepts and mechanisms: a literature review. Revi. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Humano 16, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.5007/1980-0037.2014v16n6p579 (2014).

Day, M. L., McGuigan, M. R., Brice, G. & Foster, C. Monitoring exercise intensity during resistance training using the session RPE scale. J. Strength. Cond Res. 18 (2), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-13113.1 (2004).

Sweet, T. W., Foster, C., McGuigan, M. R. & Brice, G. Quantitation of resistance training using the session rating of perceived exertion method. J. Strength. Cond Res. 18 (4), 796–802. https://doi.org/10.1519/14153.1 (2004).

Colado, J. C. et al. Concurrent validation of the OMNI-resistance exercise scale of perceived exertion with Thera-band resistance bands. J. Strength. Cond Res. 26 (11), 3018–3024. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318245c0c9 (2012).

Colado, J. C. et al. Rating of Perceived Exertion in the First Repetition is related to the total Repetitions Performed in Elastic bands training. Mot. Control. 27 (4), 830–843. https://doi.org/10.1123/mc.2023-0017 (2023). Published 2023 Aug 1.

Hopkins, W. G., Marshall, S. W., Batterham, A. M. & Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41 (1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278 (2009).

Sarmiento, S. et al. Heart rate variability during high-intensity exercise. J. Syst. Sci. Complexity. 26, 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11424-013-2287-y (2013).

James, D. V., Barnes, A. J., Lopes, P. & Wood, D. M. Heart rate variability: response following a single bout of interval training. Int. J. Sports Med. 23 (4), 247–251. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-29077 (2002).

Fisher, J. P. & Paton, J. F. The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 26 (8), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2011.66 (2012).

Pumprla, J., Howorka, K., Groves, D., Chester, M. & Nolan, J. Functional assessment of heart rate variability: physiological basis and practical applications. Int. J. Cardiol. 84 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00057-8 (2002).

Langham, M. E. & Palewicz, K. The pupillary, the intraocular pressure and the vasomotor responses to noradrenaline in rabbits. J. Physiol. 267 (2), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011816 (1977).

Langham, M. E. & Diggs, E. Beta-adrenergic responses in the eyes of rabbits, primates, and man. Exp. Eye Res. 19 (3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4835(74)90147-x (1974).

McDougal, D. H. & Gamlin, P. D. Autonomic control of the eye. Compr. Physiol. 5 (1), 439–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c140014 (2015).

Bremner, F. D., Smith, S. E. & Loewenfeld. The pupil: anatomy, physiology, and clinical applications: By Irene E. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. Price £ 180. Pp. 2278. ISBN 0-750-67143-2. Brain. 2001 124 (9), 1881–1883. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/124.9.1881 (1999).

Campbell, F., Gregory, A. Effect of size of pupil on visual acuity. Nature 187, 1121–1123. https://doi.org/10.1038/1871121c0 (1960).

Steinhauer, S. R., Siegle, G. J., Condray, R. & Pless, M. Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of pupillary dilation during sustained processing. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 52 (1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.12.005 (2004).

Kaltsatou, A., Kouidi, E., Fotiou, D. & Deligiannis, P. The use of pupillometry in the assessment of cardiac autonomic function in elite different type trained athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111 (9), 2079–2087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1836-0 (2011).

Shigeta, T. T. et al. Acute exercise effects on inhibitory control and the pupillary response in young adults. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 170, 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.08.006 (2021).

van der Wel, P. & van Steenbergen, H. Pupil dilation as an index of effort in cognitive control tasks: a review. Psychon Bull. Rev. 25 (6), 2005–2015. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1432-y (2018).

RondeelEW, van SteenbergenH, HollandRW & van KnippenbergA A closer look at cognitive control: differences in resource allocation during updating, inhibition and switching as revealed by pupillometry. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00494 (2015). Published 2015 Sep 10.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their participation in the study.

Funding

This research was funded by the following sources: (1) High-Level Public Health Technical Talent Building Program (Discipline Leader-01-01). (2) Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH 2022-1-2032). (3) National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072136). (4) Beijing Hospitals Authority’s Ascent Plan (DFL20240302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to this study. R.S. and Z.R.T. guided the entire research process, from study design to data analysis and manuscript writing. J.L.D. and X.S.W. wrote and revised the main manuscript text and analyzed the study data. J.L.D. also took responsibility for data collection and organization. C.C.H. and L.A. provided valuable suggestions for data analysis. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, J., Wang, X., Hang, C. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of quantitative pupillometry in assessing dynamic aerobic training intensity. Sci Rep 14, 26071 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77588-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77588-z