Abstract

A new control approach based on fuzzy sliding mode control (FSMC) is proposed to regulate the chaotic vibration of an axial string. Hamilton’s principle is used to formulate the nonlinear equation of motion of the axial translation string, and the von Kármán equations are used to analyse the geometric nonlinearity. The governing equations are nondimensionalized as partial differential equations and transformed into a nonlinear 3-dimensional system via the third-order Galerkin approach. An active control technique based on the FSMC approach is suggested for the derived dynamic system. By using a recurrent neural network model, we can accurately predict and effectively apply a control strategy to suppress chaotic movements. The necessity of the suggested active control method in the regulation of the nonlinear axial translation string system is proven using different chaotic vibrations. The results show that the study of the chaotic vibrations of axially translating strings requires nonlinear multidimensional dynamic systems of axially moving strings; the validity of the proposed control strategy in controlling the chaotic vibration of axially moving strings in a multidimensional form is demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Axially translating strings are extensively applied in various engineering fields. These structures are commonly found in strings1, cables2,3,4, and belts5,6,7. In engineering practice, external disturbances and other variables can cause transverse responses of axially moving strings. These vibrations may harm the structure and degrade its operational precision.

The nonlinear dynamic behaviours of axially moving strings have been investigated by many researchers in past decades. Yang and Fang8 investigated nonlinear vibrations of an axially moving viscoelastic string under the control of a fractional differentiation law. The structure’s first second-order vibration modes are investigated, and the simulation results show that with increasing fractional order, the amplitude decreases and the frequency increases. Yang9 analysed axially moving strings using multiple-scale analysis and gyroscopic mode decoupling. A comparative study illustrates the need for a high-dimensional nonlinear system of axially moving strings. Ma10 introduced a novel numerical approach for handling issues related to coupled string vibrations using, the wavelet-Galerkin method followed by spectral delayed correction. The validity of this approach was proven using both numerical simulation and experiments based on the first-order Galerkin method. Chen11 suggested an improved finite difference approach for simulating the transverse vibration of axially moving strings. The effect of transportation velocity on free nonlinear vibrations was quantitatively analysed using different truncated terms. Wang12 studied the transverse vibration of moving strings using Hamiltonian dynamics and symplectic eigenvalue analysis. Both linear and nonlinear vibration responses may be obtained using symplectic modal functions. At critical speeds, the first three vibration modes were investigated. Koivurova13 investigated the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of axial motion bands by examining the relationships among the natural frequency, axial speed, and vibration amplitude and described the main difference between an axially moving string and a beam in the region of supercritical transport velocity. Yang14 investigated the nonlinear parametric resonance of viscoelastic strings moving axially in a two-dimensional dynamic system. The numerical findings show that the fractional order influences the steady-state response. Xia15 conducted experimental research on the nonlinear characteristics of axially travelling strings. The findings of the experiments reveal that transverse responses are affected by both the velocity profile and initial tension, and that all transverse motion behaviours depend on motion parameters. Kesimli16 examined the nonlinear response of spring-supported axially translating strings. It was found that, increasing the spring rigidity, axial speed, and number of midpoint supports results in substantial nonlinear effects. Yurddaş1 examined the nonlinear responses of axially translating multi-supported strings. Different from the other studies, nonideal supports were investigated, which permits a negligible deviation from the supports at each end of the investigated string.

From the above, it can be concluded that axial vibration has a significant effect on strings, so that controlling axial vibration is particularly important. An effective control method should suppress string vibration17.

There have been many control methods proposed to suppress nonlinear vibrations of engineering structures subject to parametric uncertainties and external uncertainties18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Nozaki18 implemented two control methods namely OLFC and SDRE to control the chaotic vibration of an atomic force microscope, and the influence of parametric errors was evaluated. Peruzzi19 proved that OLFC will effectively suppress the nonlinear vibration of an electronic circuit of a resonant MEMS mass subject to parametric errors. Zhao20 investigated the vibration boundary control problem of a linear dynamic system of an axial string system related to outside disturbances and input constraints. The Lyapunov stability was applied to analyse and prove the stability of the controlled system without any reduction. Nguyen and Hong21 investigated the asymptotic stabilization of an axially translating string. Their method uses adaptive boundary control techniques to handle the complexities caused by nonlinear dynamics, variable tension, friction, and external disturbances. Li22 investigated the suppression of nonlinear responses of axially moving strings with upstream or downstream boundary suppression. It was demonstrated that boundary control, whether applied upstream or downstream, can result in exponential stabilization of the nonlinear vibration. Kelleche and Tatar23 focused on the stabilization problem of nonlinear axially moving viscoelastic strings. They used the Leibniz rule to consider the net flux passing through boundaries. Shaalan24 applied fuzzy sliding mode control (FSMC) in the polymer extrusion process. It was shown that this cutting-edge control method effectively addresses the complicated control demands and dynamics of the polymer extrusion system. Sun25 investigated the synchronization of multi-induction motors with FSMC. This work highlighted how the performance of multiple motors may be enhanced and coordinated in industrial applications through the use of FSMC. Nguyen26 introduced a novel control method that blends sliding control and adaptive fuzzy logic. The method ensures reliable and effective control in complicated and unpredictable contexts by efficiently addressing unknown system features. He and Meng27 discussed the use of an adaptive strategy in a string system to handle input delay. This study highlighted the importance of resolving delay nonlinearities without creating a delay inverse, managing system parameter uncertainties, and reducing flexible string vibrations. Korayem28 investigated the role that FSMC played in resolving issues with microcantilevers’ dynamic reactions in liquid environments, which enhanced performance and control in an atomic force microscope. Nguyen29 emphasized the integration of FSMC to handle nonlinear factors and uncertain disturbances in a control system, proving its potential to increase performance and stability.

In addition to being suitable for tasks such as speech recognition, language modelling and text generation30,31,32, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) can model and predict the behaviour of nonlinear dynamic systems33,34,35, which is crucial for understanding and controlling axially moving string systems.

In the present study, a modified FSMC is proposed to suppress the nonlinear vibration of a multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system of strings36,37. The string’s nonlinear dynamic system is derived using the Galerkin method. The influence of higher vibration modes on the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of the string is then investigated via numerical simulations based on the generated multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system. To reduce vibration in engineering practice16,38,39, a modified control strategy is finally developed in response to a multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system and then used to manage the chaotic vibration of the dynamic system.

Equation of Motion

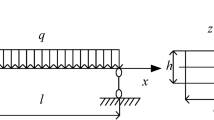

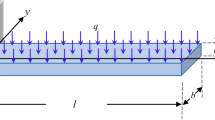

The axially moving string examined in this study is depicted in Fig. 1. The equations of motion for the string are derived using von Karman-type equations and the Hamiltonian principle. Figure 1 shows that the length of the translating string is l, and the string moves axially at a constant rate \(v_{0}\); u and w are the displacement of a point on the string along x and z axes, respectively.

Prior to deformation, the position vector of a point on the translating string, denoted by \({\mathbf{r}}\), is presented as,

where \({\text{i}}\) and \({\text{k}}\) are the unit vectors along x and z axes, respectively.

As a result, the displacement field for the string that is translating axially can be expressed as,

where \(u_{0} \left( {x\left( t \right),t} \right)\) and \(w_{0} \left( {x\left( t \right),t} \right)\) are, for a point on the string.

Then, the following can be obtained:

where the rate of translation of the string is equal to the total derivative of \(w_{0}\) with respect to time as shown below:

As a result, the translating string’s kinetic energy over volume V of the string can be expressed as,

where \(\rho\) is the mass per length.

The strain associated with Eq. (2) is obtained below by considering the von Karman equations,

Thus, the string’s overall strain energy can be calculated using the following formula:

where the elastic coefficient \(Q_{11}\) is in the same direction as \(\varepsilon_{11}\).

The force has produced zero virtual work,

Using Eqs. (5), (7), and (8), Hamilton’s principle can be expressed as,

from which the entire Lagrangian function L is obtained as

Hereafter, \(x\left( t \right)\), \(w_{0} \left( {x\left( t \right),t} \right)\), and \(u_{0} \left( {x\left( t \right),t} \right)\) will be replaced with x, \(w_{0}\), and \(u_{0}\), respectively, for clarity. Substitution of Eqs. (5), (7), and (8) into Eq. (9) yields,

where

Because the string travels axially at a constant velocity (\(\frac{{d^{2} v_{0} }}{{dt^{2} }} = 0\)), it can be obtained from Eq. (11a) that:

Equation (11c) leads to the following,

Then, the governing equation for an axially translating string can be derived from Eqs. (12a), (12b), and (11b) as follows

The strain can be calculated using the boundary conditions and nonlinear dynamic equations, as follows:

After substituting Eq. (14) into Eq. (13b), the string’s nonlinear governing equation is derived as:

Nondimensionalization

The nondimensional variables used to validate Eq. (15) are listed below:

After substituting Eqs. (16) and (15), the axially translating string’s non-dimensional governing equation can be rewritten as follows:

where, \(\eta\) is given by:

Series of Solutions

Based on the Galerkin method, \(\overline{w}_{0}\) is expanded in terms of comparison functions as follows:

The following expression for \(\varphi_{n} \left( {\overline{x}} \right)\) corresponds to the axially translating string’s pinned–pinned boundary:

Introduce Eq. (18) into Eq. (17); for convenience, substitute \(\phi_{n}\), \(w_{n}\), \(\dot{w}_{n}\), \(\ddot{w}_{n}\), v, and t with \(\varphi_{n} (\overline{x})\), \(\overline{w}_{n} \left( {\overline{t}} \right)\), \(\frac{{dw_{n} }}{dt}\), \(\frac{{d^{2} w_{n} }}{{dt^{2} }}\), \(\overline{v}_{0}\) and \(\overline{t}\); using the third-order Galerkin method, the following transformation is obtained,

The three-dimensional nonlinear dynamic system of an axially moving string with simply-supported boundaries is described by:

where,

Control design

If a nonlinear governing equation takes the following form,

The corresponding equation with control can be presented as

where U is the control input, and where \(\Delta P\left( {w,\dot{w}} \right)\) is the unknown external disturbance acting on the string.

Using the nth-order Galerkin technique, a set of second-order ordinary differential equations that account for Eq. (22) will be produced as follows:

where \(\varphi_{i} \left( {{\mathbf{W}},t} \right)\), \(u_{i}\), and \(\Delta f_{i} \left( {{\mathbf{W}},t} \right)\) are the results of \(\Phi \left( {w,\dot{w},t} \right)\), U, and \(\Delta P\left( {w,\dot{w}} \right)\) after the Galerkin method is used, and the column vector \({\mathbf{W}}\) in Eq. (23) is given below:

The nondimensional vibration of a specified point \(w_{p}\) may be obtained based on Eqs. (18) and (23),

where \(x_{p}\) indicates the location of the chosen point.

A reference vibration is given as,

where \(A_{r}\) and \(\omega_{r}\) are the frequency and amplitude of the reference signal, respectively.

U can be specified below:

where \(U_{eq}\) and \(U_{r}\) are given by,

In Eq. (27), \(\kappa\) contains the control coefficients that regulate the sliding surface, \(k_{fs}\) is given as \(\left| {\Delta F\left( {w,\dot{w}} \right)} \right| < k_{fs} \in R^{ + }\), and \(U_{fs}\) follows the fuzzy rule table in Table 117.

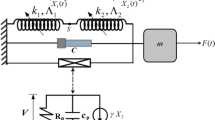

Following Table 1, the specific membership functions of the fuzzy variables, \(U_{eq}\), \(\frac{{dU_{eq} }}{dt}\) , and \(U_{fs}\) are further illustrated in Fig. 2, based on the previous studies17,40,41.

Following the control developed in Eqs. (22–27), the vibration control of a translating string is conducted via Eq. (17) as shown below,

The third-order Galerkin discretization yields the following expressions:

and \(u_{1}\), \(u_{2}\), and \(u_{3}\) are obtained as follows:

As will be demonstrated in the next section, when a mathematical model is used, the chaotic vibration of the axially moving string at a specified position may be synchronized with the desired signal.

Vibration Control

To demonstrate the suitability and efficacy of the developed approach described in the last section, numerical studies are performed. In this study, the string’s nonlinear response is first highlighted, and a chaotic vibration is discovered. Then, the developed control method is applied to synchronize the chaotic vibration of the translating string.

The following parameters are used to study the response of the axially translating string:

and the axially moving velocity is given by:

The initial conditions are given below:

Based on Eqs. (18) and (29), the vibration of the specified point is 0.3125 m along x, and the corresponding response \(w_{p}\) is given by:

where, \(w_{1,1}\), \(w_{2,1}\), and \(w_{3,1}\) are replaced with \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\) for convenience.

Vibration prediction

RNNs have been a popular topic in neural network research in recent years and are composed of an input layer, a hidden layer and an output layer. The input of the hidden layer includes the output of the hidden layer at the previous moment so that the output of the hidden layer can reflect historical information to a certain extent, and this information flows through the next neuron together with new information to affect the final output.

The feature \(\delta\) and the hidden state \(H_{t}\) at time step t are sent into the fully connected layer to calculate the output variable \(O_{t}\) of the current time step t, and \(H_{t}\) will participate in the calculation of the hidden state \(H_{t + 1}\) at the next time step \(t + 1\) for iterative calculation. A diagram of a one-unit RNN is shown in Fig. 3. From bottom to top: input state, hidden state, and output state. \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\) are the weights of the input layer, the hidden layer, and the output layer, respectively.

Compute the hidden state \(H_{t}\) at any time at time step t on the basis of the current input \(\delta_{t}\) and the previous hidden state \(H_{t - 1}\), where \(b_{h}\) is the bias parameter of the hidden layer:

\(b_{q}\) is the bias parameter of the output layer, and the output of the output layer \(O_{t}\) is given by:

Chaotic motion

The responses of the selected point on the axially-translating string are investigated in this section, and a dynamic behaviour diagnostic method named the periodicity ratio (PR) method42,43,44,45,46,47 is employed for nonlinear dynamic behaviour characterization48: when the PR value of a specific dynamic behaviour is 0, the corresponding behaviour is then characterized as chaotic.

At \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) from \(t = 0\) to \(t = 1{100}\), Fig. 4 shows the string’s response, for which the PR value is 0. The greatest amplitude of the string’s vibration can surpass 0.045. In Figs. 5 and 6, the 2D phase diagram, 3D phase diagram, and Poincaré map are presented. With the determined PR value, the wave diagram, the 2D phase diagram, the 3D phase diagram and the Poincaré map, the response of the selected point on the axially moving string is characterized as a chaotic vibration in an unstable state of the corresponding nonlinear dynamic system of the axially moving string.

As shown in Fig. 4, the amplitude is very high when the displacement depicted in the figure is considered as non-dimensional. The string’s performance may therefore be enhanced by reducing and stabilizing the chaotic motion.

Furthermore, although \(w_{1}\) in Fig. 7a has a greater impact compared to \(w_{2}\) and \(w_{3}\), as shown in Fig. 7b and c, the effects of \(w_{2}\) and \(w_{3}\) are still significant. In fact, \(w_{2}\) and \(w_{3}\) have a substantial effect on the actual vibration of the chosen spot. As a result, a nonlinear dynamic system in multiple dimensions is required for effective prediction of the dynamics of the nonlinear elastic string.

Chaotic time series prediction

After data processing, the data are divided into two parts: 70% of the data are included in the training set, for which the loss is shown by the blue line in Fig. 8, and 30% of the data are included in the test set, for which the loss is shown by the orange line in Fig. 8. All of the samples were trained 1300 times, and the number of samples in each sample batch was 256. The training is characterized by the string’s axial velocity and axial motion displacement.

Figure 8 shows that as the number of iterations increases, the loss value decreases, and the final loss function value is less than 2.5%, which provides a solid basis for a more accurate prediction and the effective application of the control to the chaotic vibration of the axially moving string.

Figure 9a shows the predicted displacement time series curves from 100 to 150 s and its subregions. Figure 9b shows the predicted velocity time series curves from 100 to 150 s and its subregions. The velocity and displacement of chaotic motion predicted using the RNN model are shown in Fig. 9. The blue curve, which shows the anticipated outcomes, can be compared with the red curve, which represents the actual dataset. Given the good agreement between the two curves, chaotic motion times can be effectively predicted using the developed method.

Amplitude synchronization

The control is applied to demonstrate its effectiveness for amplitude synchronization. The desired amplitude of the reference signal is given three different values.

When the control approach is used, the reference amplitude is set as

The remaining control coefficients, as well as the external disturbance, have the following values:

The control is applied at \(t = {140}\), as depicted in Fig. 10. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 10 and 11.

Figure 10 shows that the string requires a certain time period for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with an amplitude of 0.020 after the time period.

In Fig. 11a–c, the vibrations are presented for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). These figures show that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

The comparison between \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\) is depicted in Fig. 12. It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. As observed from the figure, the maximum amplitude of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 13 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control was applied, U first increased. As the system stabilizes, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased significantly to a relatively small number. The maximum value of U is 0.1.

When the control approach is used, the reference intended amplitude is set as

With other control factors, as well as the unidentified outside disturbance, the following values are used:

The control is applied at \(t = 140\), as depicted in Fig. 14. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = 2.02{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 14 and 15.

Figure 14 shows that the string requires only a short time period for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with a maximum amplitude of approximately 0.015.

Figure 15a–c present the vibrations for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). These figures show that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

The applied \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\) are compared in Fig. 16. It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes somewhat after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. As the shown in the figure, the maximum amplitude of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 17 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control is applied, U first increases. As the system stabilized, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased to a relatively small value. The maximum value of U is 0.12, which is larger than the previous value.

The desired reference amplitude is set during the application of the control strategy as follows:

The other control variables, as well as the unidentified external disturbance, take the following values:

The control is applied at \(t = {140}\), as depicted in Fig. 18. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 18 and 19.

Figure 18 shows that the string requires a relatively long period of time for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with an amplitude of approximately 0.010 after the brief period.

Figure 19a–c present the vibrations for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). It is observed that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

The applied \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\) are compared in Fig. 20. It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes somewhat after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. The maximum amplitude of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 21 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control was applied, U first increased. As the system stabilized, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased significantly to a small value. The maximum value of U is 0.50, which is four times larger than the previous value.

Frequency synchronization

The control is applied to demonstrate its efficacy for frequency synchronization. The desired frequency of the reference signal is given one of three different values.

The preferred reference frequency is chosen when the control strategy is applied according to:

Considering other control factors, as well as unidentified outside disturbances, the following values are used:

The control is applied at \(t = {140}\), as depicted in Fig. 22. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 22 and 23.

Figure 22 shows that the string requires only a short period of time for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with an angular velocity close to 0.0277.

Figure 23a–c present the vibrations for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). These figures show that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

Figure 24 compares the applied \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\). It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes somewhat after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. The angular velocity of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 25 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control is applied, U first increases. As the system stabilized, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased significantly to a small value. The maximum value of U is 0.034.

The desired frequency of the reference is set by the control strategy according to:

and other control parameters, as well as the unidentified outside disturbance, have the following values:

The control is applied at \(t = {140}\), as depicted in Fig. 26. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 26 and 27.

Figure 26 shows that the string needs only a relatively short period of time for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with an angular velocity close to 0.0184.

Figure 27a–c present the vibrations for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). These figures show that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

Figure 28 compares the applied \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\). It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes somewhat after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. The maximum amplitude of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 29 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control is applied, U first increases. As the system stabilized, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased significantly to a small value. The maximum value of U is 0.060, which is almost two times larger than the previous value.

As the control strategy is implemented, the desired frequency of the reference is set according to:

For other control factors, as well as the unidentified outside disturbance, the following values are used:

The control is applied at \(t = {140}\), as depicted in Fig. 30. The vibrations of the string at \(v_{0} = {2}{\text{.02}}{m \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {m s}} \right. \kern-0pt} s}\) are displayed in Figs. 30 and 31.

Figure 30 shows that the string requires a short period of time for stabilization following the use of the control approach. The vibrations of the chosen point, \(w_{p}\), are shown from \(t = {0}\) to \(t = 4000\). The chaotic vibration is stabilized into a periodic motion with an angular velocity close to 0.0092 after a brief period.

Figure 31a–c present the vibrations for \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\), and \(w_{3}\). It is observed that the control approach eventually stabilizes each displacement of the axially translating string, converting it from a chaotic motion into a periodic motion.

Figure 32 compares the applied \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\). It is observed that the maximum amplitude of the string’s response changes somewhat after the string is stabilized by the use of the control approach. The maximum amplitude of \(w_{p}\) is close to that of \(w_{r}\).

Figure 33 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control is applied, U first increases. As the system stabilized, the maximum value of U, which is represented by a periodic wave diagram in the figure, decreased significantly to a small value. The maximum value of U is 0.068, which is slightly larger than the previous value.

Influence of parametric errors

Following the previous research on the influence of parametric errors18,19, chaotic vibration control is applied in the case of random parametric errors to further examine the validity of the control approach. With the same control configuration given in the first case of Amplitude Synchronization, the parameter in Eq. (17) now includes an error of ± 20% as follows:

where, \(r\left( t \right)\) is a normally distributed random function based on the previous research19.

With the coefficient in Eq. (33) substituted into Eq. (17), vibration control is applied, and the actual response at the selected point is shown in Fig. 34. Although the amplitude of the suppressed response at the selected point is slightly larger than that of the first case of Amplitude Synchronization, clearly \(w_{p}\) can still be suppressed in the case of random parametric errors.

The first three mode vibrations are shown in Fig. 35a–c, which also demonstrate the influence of the control on the response of the studied structure.

The comparison between \(w_{r}\) and \(w_{p}\) is depicted in Fig. 36. Although at the beginning of the control the maximum amplitude of the string’s response is more than 0.06, which is larger than that of the first case of Amplitude Synchronization, the difference between the suppressed \(w_{p}\) and \(w_{r}\) is still small.

Figure 37 displays the input for control, U. Immediately after the control was applied, U first increased to a maximum value around 0.16, which is almost 50% higher than the observed value 0.11 in the first case of Amplitude Synchronization. However, once \(w_{p}\) is stabilized, the demanded control value to maintain the control is still close to that in the first case of Amplitude Synchronization.

Conclusions

Using a novel control strategy developed based on the FSMC, the present work provides an active control strategy for the chaotic motion control of an axially moving string. Using the third-order Galerkin approach, a multidimensional nonlinear system of an axially moving string is derived. A control strategy is subsequently established to synchronize the obtained multidimensional dynamic system. The numerical study demonstrated the efficacy of the control strategy in the case of both external disturbance and random parametric errors. The results obtained in this study will be beneficial for multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system vibration control of axially moving strings in engineering. Drawing on the results of this study, some additional conclusions can be made:

-

(1)

Higher-order vibrations must be introduced at this phase to analyse the vibration of an axially moving string under sinusoidal stimulation more thoroughly and precisely, particularly when chaotic vibrations must be considered. Consequently, while controlling the vibration of a nonlinear string system, the influence of higher-order vibrations must be considered.

-

(2)

The effectiveness of this control method is demonstrated by the ability of the established active control strategy to effectively synchronize the response of the axial moving strings in the multidimensional dynamic system with the desired reference signal, which is significantly controlled under both the frequency and amplitude parameters.

-

(3)

This multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system based on the FSMC control approach plays an important role in the research of chaotic vibrations of axially moving strings, significantly enhancing both the efficiency and reliability of control.

-

(4)

The modified control strategy is further validated in the case of both external disturbance and parametric errors. Though larger response amplitude is observed and higher control input is demanded at the beginning of the control, generally the response of the axially moving string subjected to parametric error can still remain suppressed with the control strategy.

-

(5)

By using the RNN model, we can accurately predict and effectively apply the control strategy to suppress chaotic movements; therefore, the amplitude of the string is continuously reduced, and the period of the string can also be increased.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yurddaş, A., Özkaya, E. & Boyacı, H. Nonlinear vibrations of axially moving multi-supported strings having non-ideal support conditions. Nonlinear Dyn. 73, 1223–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-012-0650-5 (2013).

Gao, F., Wang, R. & Lai, S. K. Bifurcation and chaotic analysis for cable vibration of a cable-stayed bridge. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 20, 2071004. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219455420710042 (2020).

Su, X., Kang, H., Chen, J., Guo, T. & Zhao, Y. Experimental study on in-plane nonlinear vibrations of the cable-stayed bridge. Nonlinear Dyn. 98, 1247–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-019-05259-0 (2019).

Macdonald, J. H. G. Multi-modal vibration amplitudes of taut inclined cables due to direct and/or parametric excitation. J. Sound Vib. 363, 473–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2015.11.012 (2016).

Ding, H., Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. W. Free and forced nonlinear vibration of a transporting belt with pulley support ends. Nonlinear Dyn. 92, 2037–2048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4179-0 (2018).

Sun, Y., Shangguan, W. B., Jiang, J. & Rakheja, S. Modeling of serpentine belt accessory drive system coupled vibrations and utilizing nonlinear tensioner to enhance performances. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 178, 109308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2022.109308 (2022).

Ding, H. & Li, D. P. Static and dynamic behaviors of belt-drive dynamic systems with a one-way clutch. Nonlinear Dyn. 78, 1553–1575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-014-1534-7 (2014).

Yang, T. & Fang, B. Asymptotic analysis of an axially viscoelastic string constituted by a fractional differentiation law. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 49, 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2012.10.001 (2013).

Yang, X. D., Wu, H., Qian, Y. J., Zhang, W. & Lim, C. W. Nonlinear vibration analysis of axially moving strings based on gyroscopic modes decoupling. J. Sound Vib. 393, 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2017.01.035 (2017).

Ma, X., Wu, B., Zhang, J. & Shi, X. A new numerical scheme with Wavelet-Galerkin followed by spectral deferred correction for solving string vibration problems. Mech. Mach. Theory 142, 103623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.103623 (2019).

Chen, L. Q., Zhao, W. J. & Zu, J. W. Simulations of transverse vibrations of an axially moving string: a modified difference approach. Appl. Math. Comput. 166, 596–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2004.07.006 (2005).

Wang, Y., Huang, L., Liu, X. & Wang, K. Eigenvalue and stability analysis for transverse vibrations of axially moving strings based on Hamiltonian dynamics. Acta Mech. Sinica 21, 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10409-005-0066-2 (2005).

Koivurova, H. The numerical study of the nonlinear dynamics of a light, axially moving string. J. Sound Vib. 320, 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2008.07.026 (2009).

Yang, T. Z., Yang, X., Chen, F. & Fang, B. Nonlinear parametric resonance of a fractional damped axially moving string. J. Vib. Acoust. 135, 064507. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4024779 (2013).

Xia, C., Wu, Y. & Lu, Q. Experimental study of the nonlinear characteristics of an axially moving string. J. Vib. Control 21, 3239–3253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546314520832 (2015).

Kesimli, A., Özkaya, E. & Bağdatli, S. M. Nonlinear vibrations of spring-supported axially moving string. Nonlinear Dyn. 81, 1523–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-015-2086-1 (2015).

Yau, H. T., Wang, C. C., Hsieh, C. T. & Cho, C. C. Nonlinear analysis and control of the uncertain micro-electro-mechanical system by using a fuzzy sliding mode control design. Comput. Math. Appl. 61, 1912–1916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2010.07.019 (2011).

Nozaki, R., Balthazar, J. M., Tusset, A. M. & Bueno, Á. M. Nonlinear control system applied to atomic force microscope including parametric errors. J. Control Autom. Electric. Syst. 24, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40313-013-0034-1 (2013).

Peruzzi, N. et al. The dynamic behavior of a parametrically excited time-periodic MEMS taking into account parametric errors. J. Vib. Control 22, 4101–4110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546315573913 (2016).

Zhao, Z., Ma, Y., Liu, G., Zhu, D. & Wen, G. Vibration control of an axially moving system with restricted input. Complexity 2019, 2386435. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2386435 (2019).

Nguyen, Q. C. & Hong, K. S. Asymptotic stabilization of a nonlinear axially moving string by adaptive boundary control. J. Sound Vib. 329, 4588–4603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2010.05.021 (2010).

Li, T., Hou, Z. & Li, J. Stabilization analysis of a generalized nonlinear axially moving string by boundary velocity feedback. Automatica 44, 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2007.06.004 (2008).

Kelleche, A. & Tatar, N. Exponential decay for a nonlinear axially moving viscoelastic string. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2020, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.6932 (2020).

Shaalan, A. S., El-Nagar, A. M., El-Bardini, M. & Sharaf, M. Embedded fuzzy sliding mode control for polymer extrusion process. ISA Trans. 103, 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2020.03.026 (2020).

Sun, C., Gong, G., Yang, H. & Wang, F. Fuzzy sliding mode control for synchronization of multiple induction motors drive. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 41, 3223–3234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142331218817100 (2019).

Nguyen, S. D., Choi, S. B. & Seo, T. I. Adaptive fuzzy sliding control enhanced by compensation for explicitly unidentified aspects. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 15, 2906–2920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-016-0569-6 (2017).

He, W. & Meng, T. Adaptive control of a flexible string system with input hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 26, 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2017.2669158 (2018).

Korayem, A. H., Ghasemi, P. & Korayem, M. H. The effect of liquid medium on vibration and control of the AFM piezoelectric microcantilever. Microsc. Res. Tech. 83, 1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.23535 (2020).

Nguyen, S. D., Vo, H. D. & Seo, T. I. Nonlinear adaptive control based on fuzzy sliding mode technique and fuzzy-based compensator. ISA Trans. 70, 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2017.05.011 (2017).

Arslan, R. S. & Barışçı, N. Development of output correction methodology for long short term memory-based speech recognition. Sustainability 11, 4250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154250 (2019).

Jiang, J. et al. Enhancements of attention-based bidirectional LSTM for hybrid automatic text summarization. IEEE Access. 9, 123660–123671. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3110143 (2021).

Shuang, K., Tan, Y., Cai, Z. & Sun, Y. Natural language modeling with syntactic structure dependency. Inf. Sci. 523, 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.03.022 (2020).

Huang, B., Zheng, H., Guo, X., Yang, Y. & Liu, X. A novel model based on DA-RNN network and skip gated recurrent neural network for periodic time series forecasting. Sustainability 14, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010326 (2021).

Sun, Y., Zhang, L. & Yao, M. Chaotic time series prediction of nonlinear systems based on various neural network models. Chaos Solitons Fract. Appl. Sci. Eng. Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 175, 113971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2023.113971 (2023).

Yang, B., Yin, K., Lacasse, S. & Liu, Z. Time series analysis and long short-term memory neural network to predict landslide displacement. Landslides 16, 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-018-01127-x (2019).

Yang, K.-J., Hong, K.-S. & Matsuno, F. Energy-based control of axially translating beams: Varying tension, varying speed, and disturbance adaptation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 13, 1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2005.854368 (2005).

Kelleche, A., Saedpanah, F. & Abdallaoui, A. On stabilization of an axially moving string with a tip mass subject to an unbounded disturbance. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.9413 (2023).

Wang, J. & Van Horssen, W. T. On resonances and transverse and longitudinal oscillations in a hoisting system due to boundary excitations. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 5079–5106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-022-08052-8 (2023).

Scheidl, J. & Vetyukov, Y. Review and perspectives in applied mechanics of axially moving flexible structures. Acta Mech. 234, 1331–1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00707-023-03514-5 (2023).

Tairidis, G., Foutsitzi, G., Koutsianitis, P. & Stavroulakis, G. E. Fine tuning of a fuzzy controller for vibration suppression of smart plates using genetic algorithms. Adv. Eng. Softw. 101, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.019 (2016).

Yau, H. T., Kuo, C. L. & Yan, J. J. Fuzzy sliding mode control for a class of chaos synchronization with uncertainties. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 7, 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJNSNS.2006.7.3.333 (2006).

Dai, L., Sun, L. & Chen, C. A control approach for vibrations of a nonlinear microbeam system in multi-dimensional form. Nonlinear Dyn. 77, 1677–1692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-014-1409-y (2014).

Wang, L. & Dai, L. Chaotic time series prediction of multi-dimensional nonlinear system based on bidirectional LSTM model. Adv. Theory Simul. 6, 2300148. https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.202300148 (2023).

Dai, L. Control of an extending nonlinear elastic cable with an active vibration control strategy. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 19, 3901–3912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnsns.2014.03.034 (2014).

Dai, L. & Wang, L. Nonlinear analysis of high accuracy and reliability in traffic flow prediction. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1515/nleng-2020-0016 (2020).

Jazar, R. N. & Dai, L. Nonlinear Approaches in Engineering Applications 2. (Springer, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6877-6

Dai, L. & Jazar, R. N. Nonlinear Approaches in Engineering Applications: Applied Mechanics, Vibration Control, and Numerical Analysis (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09462-5

Dai, L. Nonlinear Dynamics of Piecewise Constant Systems and Implementation of Piecewise Constant Arguments (World Scientific, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1142/6882

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the FuShun Revitalization Talents Program (FSYC202107004) and Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (JYTMS20231436).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft. J.L.: Acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript. L.W.: Methodology, writing -review & editing. Y.L.: Writing -review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Lv, J., Wu, L. et al. Chaotic vibration control of an axially moving string of multidimensional nonlinear dynamic system with an improved FSMC. Sci Rep 14, 26495 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77632-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77632-y