Abstract

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a world public health problem that enhances the risk of premature coronary artery disease (CAD) with a high incidence of acute coronary syndrome. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical and angiographic characteristics of the patients with and without FH who had ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). It included 690 patients who presented with the first attack of STEMI and underwent primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PPCI). The patients were analyzed to diagnose FH according to the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN) criteria. All angiograms were analyzed for the number of diseased vessels, Syntax score, thrombus burden grade, and final Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade. The majority of patients were male (72.6%) with a mean age of 54 ± 12 years. Based on DLCN criteria, they were classified into unlikely/possible FH (86.1%) and probable/definite FH (13.9%) groups. Probable/definite FH patients were significantly younger, and higher incidence of males < 55 years compared with unlikely/possible FH patients (p < 0.001 for each). Moreover, probable/definite FH patients had a higher frequency of three-vessel disease (p = 0.007) and Syntax score (p < 0.001) with a moderate positive correlation with the DLCN score (r = 0.592, p < 0.001). Furthermore, probable/definite FH patients showed a higher thrombus burden and final TIMI slow/no-reflow when compared to the unlikely/possible FH patients (p = 0.006 and p = 0.027, respectively). Patients with probable/definite FH and LDL-C level were independent predictors of high thrombus burden besides males < 55 years, and the number of diseased vessels. In conclusion, STEMI patients with FH were younger males and associated with severe CAD with frequent multivessel CAD, high anatomical complexity of CAD, and frequent high thrombus burden. Furthermore, FH was one of the predictors of high thrombus burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a common autosomal dominant genetic disease characterized by elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels1. The most often used criteria for diagnosis of FH are the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN) criteria2.

FH increases the risk of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD), mainly CAD, and premature death at a young age3,4. The incidence of acute coronary syndrome is 15–20 times higher in patients with untreated FH compared to those without FH5,6. In addition, FH patients were at a 2.34-fold increased risk of recurrent acute coronary syndrome than those without FH7. Therefore, LDL-C is important in the assessment of acute coronary syndrome patients8.

Many studies demonstrated that patients with FH had more severe CAD than patients without FH using the Gensini score9,10,11. Few studies showed that FH increases the complexity of CAD lesions12. However, in FH patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), there is limited data about the complexity of CAD, thrombus burden grade, and final Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade that affects the patient’s prognosis. Also, clinical data on FH patients with STEMI is still relatively scarce.

Therefore, this study’s objectives were; first, to compare the demographic and clinical features of patients with FH who have experienced STEMI to those without FH. Second, to evaluate the angiographic characteristics of these patients, focusing on the severity and anatomical complexity of coronary artery lesions and the grade of coronary thrombus burden.

Methods

Study population

The present study included patients who presented with the first attack of acute STEMI (type 1 myocardial infarction) at Assiut University Heart Hospital and underwent PPCI between August 2020 and July 2021. All patients were diagnosed with acute STEMI (type 1 myocardial infarction) according to the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction13 and were eligible for PPCI. Patients with acute STEMI who were referred for coronary bypass graft surgery, receiving fibrinolytic therapy, undergoing conservative strategy, had prior use of antihyperlipidemic drugs, or had clinical and laboratory evidence of secondary hyperlipidemia (such as hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, Cushing’s syndrome, pheochromocytoma, or obstructive jaundice) were excluded from the study.

Sample size calculation

Based on the previous estimated prevalence of the FH in patients presenting with myocardial infarction, an estimated minimum sample size was 342 patients which was multiplied by 2 design effect to compensate for not using a simple random sampling technique. Therefore, a net sample was 684 patients needed to carry out this study. The following equation for the sample size for descriptive study design14 was used:

Z1 – α /2 represents the number of standard errors from the mean for the corresponding level of confidence. (At 95% CI or 5% level of significance (type-I error) it is 1.96 and at 99% CI it is 2.58)

P is the expected prevalence based on previous research6.

D is the margin of error or precision; the absolute precision required on either side of the proportion.

Study design

A detailed history, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), and blood sample were taken upon the patient’s arrival at the hospital. All patients underwent a PPCI by an expert interventional cardiologist. Only the infarct-related artery was targeted. All angiograms were reviewed and analyzed in the core laboratory by two interventional cardiologists blinded to all data. From the worst angiographic view, the lesions were evaluated visually in several projections. Significant CAD was defined as stenosis of ≥ 60% of one major coronary artery or ≥ 50% of the left main coronary artery. Patients were classified as having 1, 2, or 3 vessels by counting the number of affected vessels. Stenosis of ≥ 50% in the left main coronary artery was considered a 2-vessel disease.

The Syntax Score was used to assess the complexity of coronary artery disease15. It was calculated for each patient by scoring all the coronary artery lesions with diameter stenosis ≥ 50% in vessels ≥ 1.5 mm using a web-based (http://www.syntaxscore.org) or smartphone application.

Intracoronary thrombus burden was angiographically assessed and classified into the following grades (Fig. 1); in grade 0, no angiographic characteristics of thrombus are present; in grade 1, a possible thrombus is present; in grade 2, there is a definite thrombus, with the greatest dimensions ≤ 1/2 the vessel diameter; in grade 3, there is a definite thrombus but with greatest linear dimension > 1/2 but < 2 vessel diameters; and in grade 4, there is definite thrombus, with the largest dimension ≥ 2 vessel diameters16. If the vessel is occluded, the thrombus burden was graded into one of the previous grades after flow achievement either with wire crossing or a small balloon (1.5 mm diameter) passage or dilatation. Intracoronary thrombus burden grade 4 was considered a high thrombus burden.

The final flow in the infarcted related artery after PPCI was visually calculated according to the TIMI study classification17. The flow of TIMI was graded as follows: TIMI flow Grade 0: no antegrade flow; TIMI flow Grade I: Partial contrast penetration beyond the occluded segment with incomplete distal filling; TIMI flow Grade II: Patent epicardial artery with delayed contrast filling of the entire distal artery; TIMI flow Grade III: patent epicardial artery with normal flow. TIMI flow grade < III was defined as slow/no-reflow.

The patients were analyzed to diagnose FH according to the DLCN criteria2.All studied patients were examined by transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography using a GE VIVDE S5 ultrasound system device during their hospital stay. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LV EF) was assessed using the biplane method of disks (modified Simpson method) and the left ventricular wall motion score index (WMSI) was calculated18. In-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which is defined as a composite of mortality, heart failure, re-infarction, and stroke, were recorded.

Diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia

Familial hypercholesteremia was diagnosed using DLCN criteria (Table 1). DLCN criteria are based on family history of premature CVD in first-degree relatives, their own CVD history, physical examination findings such as tendon xanthomas or corneal arch, among other parameters, and untreated LDL-C levels2. In this study, genetic testing was not carried out. DLCN score was calculated and a total point score of > 8 is considered definite FH, 6–8 is probable FH, 3–5 is possible FH, and < 3 is unlikely FH (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Data were verified, coded, and analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 24, IBM, and Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics; means, standard deviations, medians, ranges, frequency, and percentages were calculated. Test of significances, Chi-square/Fisher’s Exact/Monte Carlo Exact test was used to compare the difference in the distribution of frequencies among different groups. For continuous variables, an independent sample t-test test was carried out to compare the means between groups. The correlation was performed using the Spearman Rank correlation coefficient. Univariate logistic regression analysis was calculated to investigate the independent significant predictors of high thrombus burden (Odds Ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value). Predictors with proven statistical significance from the univariate analyses were further included in the multivariable logistic regression models to investigate the adjusted significant predictors of high thrombus burden (adjusted OR, 95% CI, and p-value). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

During the period of the study, 1,200 patients were presented with the first attack of acute STEMI (type 1 myocardial infarction) and assessed for eligibility. A total of 690 patients were in the final analysis of the present study (Fig. 2). The majority of studied patients were male (501 patients, 72.6%) with an overall mean age of 54 ± 12 years. Nearly, a quarter of them had hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (22.3%, and 25.2%, respectively), and 26.4% were smokers. Table 2 shows the rest of the total patients’ characteristics.

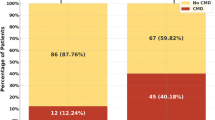

Based on DLCN criteria for diagnosis of FH, it was unlikely in 418 (60.6%) patients, possible in 176 (25.5%) patients, probable in 90 (13.4%) patients, and 6 (0.9%) patients reached a definite diagnosis (Table 1). Therefore, the study population was classified into two groups: unlikely/possible FH group (594 patients, 86.1%) and probable/definite FH group (96 patients, 13.9%). Probable/definite FH patients were significantly younger, had a higher incidence of males < 55 years, lower incidence of hypertension, and, as expected, had a prominent family history of premature CAD and/or vascular disease compared with unlikely/possible FH patients (p < 0.001, < 0.001, 0.05, and < 0.001 respectively) (Table 2). On admission, the location of STEMI was comparable for both groups (p = 0.392), and the majority of patients in both groups presented with anterior STEMI. Moreover, the Killip clinical class of patients matched in both groups (p = 0.776) with more than 90% being class I in each group. In addition, LV EF was mildly reduced in both groups to the same extent with similar LV WMSI. The length of hospital stay was similar for both groups with a median length of stay of 3 (2–7) days. In-hospital MACE was similar in both groups (9.6% vs. 13.5%, p = 0.235).

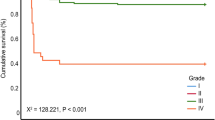

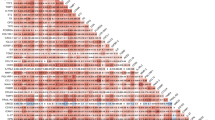

Patients’ angiographic and procedure characteristics are shown in Table 3. No significant difference between the unlikely/possible FH and the probable/definite FH groups was found for the location of the infarcted-related artery (p = 0.462). Compared to the unlikely/possible FH group, patients in the probable/definite FH group had a higher Syntax score (24.91 ± 5.8 vs. 18.66 ± 4.0, p < 0.001) and more frequent three-vessel disease (29.2% vs. 17.5%, p = 0.007) (Fig. 3A). Moreover, Fig. 4 shows that the DLCN score had a significant positive moderate correlation with the Syntax score (r = 0.592, p < 0.001) among the total studied patients. In addition, a significantly high thrombus burden and final TIMI slow/no-reflow were found among patients of the probable/definite FH group compared with the unlikely/possible FH group (p = 0.006 for the former and p = 0.027 for the latter) (Fig. 3B & C, respectively) with a trend toward the use of Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients of the probable/definite FH group (p = 0.07). Moreover, in multivariate analysis of the studied patients, males < 55 years, LDL-C level, probable/definite FH, and the number of diseased vessels were independent predictors of high thrombus burden (p-value 0.02, < 0.001, 0.004 and 0.019 respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, the characteristics of patients with probable/definite FH hospitalized for STEMI differ from patients with unlikely/possible FH; they were younger (12 years younger) with predominantly male patients with premature CAD (< 55 years), lower incidence of hypertension, and had a higher prevalence of history and/or family history of premature CVD. FH is an autosomal dominant inherited genetic disorder that has severely elevated LDL-C levels since birth19. This elevated LDL-C level leads to accelerated atherosclerosis that consequently raises the risk of premature CAD20. Thence in our study, STEMI patients with probable/definite FH were younger age and had a higher incidence of a history of premature CVD. FH is inherited in families in an autosomal dominant19, therefore it was expected that a family history of premature CVD was significantly prevalent in probable/definite FH. These findings are supported by the results of many previous studies and registries11,21,22,23. In general, there is no sex difference in patients with FH7,23. However, we found that premature CAD was significantly more prevalent among males (age < 55 years) with probable/definite FH. These findings are comparable to those previously published data from the CASCADE-FH registry, British Columbia FH Registry, and other authors24,25,26. British Columbia FH Registry with a diagnosis of probable or definite FH according to DLCN Criteria, the age of the first cardiovascular event in males was significantly younger than in females (p = 0.01)25. Hypertension prevalence increased progressively with age. Based on data from the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population: the age-standardized prevalence of hypertension for individuals aged 35 to 49 years and 50 to 59 years were around 12.1% and 27.2%, respectively27,28. In the present study, the mean age in unlikely/possible and probable/definite FH groups was 58 and 46 years, respectively. This goes along with our finding that hypertension was significantly prevalent among unlikely/possible FH patients (23.6% and 14.6%, p = 0.5) which have already been reported in several cohorts7,11,12,21,29.

Our study revealed that the clinical presentation and in-hospital course of STEMI patients who underwent PPCI were similar in both unlikely/possible FH and probable/definite FH groups. In both groups, most of the patients presented with anterior STEMI, and the majority had functional Killip class I with mildly reduced EF. Moreover, in-hospital MACE did not differ in both groups. In the general population, anterior wall STEMI is the common location and this is not different in patients with FH as our study demonstrated. RICO study, which is a survey that has included all consecutive patients > 18 years hospitalized for myocardial infarction in the region of Côte d’Or (France) since 2001, supports our findings as showed that anterior wall STEMI was the most common site in patients with no FH and FH (65% for the former and 56% for the latter, p = 0.154)12. Moreover, similar to our study, the French registry of Acute ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI 2005 and 2010) revealed that the majority of the patients with no FH and FH presented with functional Killip class I (84% versus 87.5% respectively, p = 0.246 )21. Our study showed that patients’ EF was mildly reduced in both groups (49 versus 48, p = 0.592). Other studies such as the RICO study and FAST-MI 2005 and 2010 registry12,21 showed good EF (55 versus 55 for the former and 52 versus 53 for the latter) in both groups because these studies included patients with STEMI and non-STEMI and our study included only STEMI patients. In the present study, patients with probable/definite FH had a similar risk for in-hospital MACE as those with unlikely/possible FH which may be attributed to quite comparable patients’ comorbidities in both groups. Few studies addressed the in-hospital complications or MACE as a part of the long-term outcome of patients with acute coronary syndrome and FH7,12,21,29,30. Some of these studies12,21,29 demonstrated similar in-hospital complications (heart failure, recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, and death) as the studied population baseline characteristics in both non-FH and FH groups were comparable. The other studies7,30 showed few differences regarding in-hospital outcomes compared to our study as they showed a higher in-hospital all-cause mortality in patients with non-FH. They included a heterogeneous population (STEMI, non-STEMI, and unstable angina) and the patients with non-FH were older and exposed to many comorbidities compared to those with FH.

Few studies tackled the angiographic characteristics of patients with FH 9–12,31−34. The present study boosts the findings of the previous studies and highlights another aspect of the angiographic features of patients with FH and presented with STEMI. In the present study, the severity of CAD is characterized by frequent three-vessel disease (Fig. 3A), and the anatomical complexity of CAD is distinguished by a high Syntax score (Table 3) in patients with probable/definite FH. These findings suggest that the elevated cholesterol burden in FH, which starts at an early age, and high DLCN score are associated with CAD severity and anatomical complexity. This speculation is supported by the significant positive correlation between the DLCN score and the Syntax score in the present study (Fig. 4). These data are matched with previous studies’ findings in which the severity of CAD was assessed either by frequency of multi-vessel CAD, Gensini score31, or both. They reported frequent multi-vessel CAD in FH patients, while non-FH patients had more frequent one-vessel CAD12,32,33,34,35. Two other studies showed that the Gensini score was significantly increased with the definite/probable FH diagnosis in both men and women compared to possible and unlikely FH9,10. In addition, Wang et al. stated that FH was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of multi-vessel CAD and a higher Gensini score11. Only three studies address the anatomical complexity of CAD in patients with FH11,12,35. Wang et al.11 assessed only chronic total occlusion and reported its higher prevalence among FH patients compared with non-FH patients (45.9% vs. 29.9%). Yasuda and his colleagues35 defined complex lesions by the presence of one or more of the following features: irregular borders, abrupt lesion edges perpendicular to the vessel wall, ulceration, or the presence of a thrombus. They found that patients with FH had more prevalent total obstructive and complex lesions compared with non-FH patients (56% vs. 11%; p < 0.01 for the former and 38% vs. 15%; p < 0.01 for the latter). Yao and Coworkers12 focused on the complexity of the lesions using Syntax score and prespecified lesions complex criteria from the CHAMPION-PHOENIX and DAPT studies36,37. They showed that patients in the FH group had a higher initial Syntax score (p = 0.005), more multiple lesions (p = 0.022), bifurcation lesions (p = 0.017), and calcified lesions (p = 0.033) with a non-significant trend towards more multiple complex lesions > 1 (p = 0.053) compared to the non-FH group. These results are in line with our findings as we believe that the Syntax score included all components of the lesion’s complex criteria in the CHAMPION-PHOENIX and DAPT studies. Therefore, the Syntax score expresses the anatomical complexity of CAD. These studies were retrospective, included patients with chronic coronary syndrome, acute coronary syndrome (STEMI, non-STEMI, and unstable angina), or acute myocardial infarction (STEMI, and non-STEMI), and included patients on statin therapy that affect the lipogram compared to our study that was a prospective study, focused only on patients with STEMI, and excluding patients on statin therapy. In addition, some DLCN criteria such as tendon xanthomas, corneal arches, and/or family history of premature CAD and/or vascular disease were not collected in these studies.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to evaluate the thrombus burden and its predictors in patients with probable/definite FH hospitalized for STEMI who underwent PPCI. In the current study, the high thrombus burden was significantly more frequent in patients with probable/definite FH, and LDL-C level was one of the predictors of high thrombus burden. Elevated LDL-C promotes lipid-rich core atheromatous plaque with a honeycomb-like accumulation of foam cells, cholesterin clefts, and blood infiltration from the lumen to atheromatous plaque increasing intra-plaque pressure and causing atheromatous plaque rupture with intracoronary thrombosis development38. This is the basic pathophysiologic mechanism in patients with acute coronary syndrome. There are several speculated potential reasons for high thrombus burden in patients with FH and STEMI, primarily related to elevated LDL-C and its effects on the vascular system. Human LDL-C can be chromatographically divided into 5 subfractions (L1-L5) with increasing electronegativity39. The most electronegative L5 is significantly higher in FH compared with normal subjects (2–5% vs. 0.6% of total plasma LDL-C, respectively)40. L5 in STEMI patients increased adenosine 5 diphosphate, platelet P-selectin expression, and GP IIb/IIIa activation, thereby triggering platelet activation and aggregation with thrombus formation41. Moreover, LDL-C consists of aggregating LDL-C, and Lp(a) constitutes 30–45% of total LDL-C42. Patients with FH, especially those with CVD, had higher Lp(a) plasma levels43. In addition to the pro-atherosclerotic effects of Lp(a), it has anti-fibrinolytic and pro-thrombotic properties through impairment of plasmin generation and stimulation of platelet aggregation44. Therefore, elevated Lp(a) is associated with an increased risk of high thrombus burden in STEMI patients45. Furthermore, it has been shown that the platelet aggregation parameters and mean platelet volume in patients with FH were significantly increased compared to patients with non-FH46,47. Hence, these findings suggest that increased platelet reactivity may provoke thrombus formation and increase thrombus burden in patients with FH. In addition, plasma fibrinogen and coagulation factor VIII levels are significantly higher in patients with FH and CAD48, and polymorphism of the LDL-receptor, the main mechanism of high LDL-C in FH families, is related to increased coagulation factor VIII and accelerated coagulation49.

Limitations

The current study has some limitations that one has to consider. Firstly, this study was a single-center study so a multicenter large-scale study may be more informative with different groups. Secondly, this study was observational, as with any observational analysis, we were unable to conclude causal relationships correlated to measured and unmeasured confounding biases. Nevertheless, a large sample size was used to increase the power of the study to identify real effects. Thirdly, genetic analysis was not performed to confirm FH in this study, which may have contributed to some degree of underdiagnosis of FH. However, some studies showed that definite FH diagnosis based on DLCN criteria offers a comparable detection rate to genetic analysis50,51.

In conclusion, STEMI patients with FH were more prone to be younger males, having a history of CAD and a family history of premature CVD with a lower incidence of hypertension. In addition, they were associated with severe CAD with frequent multivessel CAD and high anatomical complexity of CAD. Furthermore, high thrombus burden was frequently encountered among patients with FH with LDL-C level as one of its predictors besides males < 55 years, and the number of diseased vessels.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- DLCN:

-

Dutch Lipid Clinic Network

- ECG:

-

electrocardiogram

- FH:

-

familial hypercholesterolemia

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LV EF:

-

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE:

-

major adverse cardiovascular events

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PPCI:

-

primary percutaneous coronary interventions

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- TIMI:

-

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

- WMSI:

-

wall motion score index

References

Kastelein, J. J. P., Reeskamp, L. F. & Hovingh, G. K. Familial hypercholesterolemia: the most common monogenic disorder in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2567–2569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.058 (2020).

Defesche, J. C., Lansberg, P. J., Umans-Eckenhausen, M. A. & Kastelein, J. J. Advanced method for the identification of patients with inherited hypercholesterolemia. Semin Vasc Med. 4, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-822987 (2004).

Benn, M., Watts, G. F., Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Familial hypercholesterolemia in the Danish general population: prevalence, coronary artery disease, and cholesterol-lowering medication. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 3956–3964. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1563 (2012).

Mainieri, F., Tagi, V. M. & Chiarelli, F. Recent Advances on Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Children and Adolescents. Biomedicines 10, doi: (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10051043

Nordestgaard, B. G. et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 34(a), 3478–3490. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht273 (2013).

Singh, A. et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia among young adults with myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 2439–2450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.059 (2019).

Kheiri, B. et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia related admission for acute coronary syndrome in the United States: incidence, predictors, and outcomes. J. Clin. Lipidol. 15, 460–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2021.04.005 (2021).

Acikgoz, E., Acikgoz, S. K., Yaman, B. & Kurtul, A. Lower LDL-cholesterol levels associated with increased inflammatory burden in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992). 67, 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.67.02.20200548 (2021).

Li, J. J. et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia phenotype in Chinese patients undergoing coronary angiography. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 37, 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308456 (2017).

Li, S. et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in very young myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 8, 8861. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27248-w (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Comparison of long-term outcomes of young patients after a coronary event associated with familial hypercholesterolemia. Lipids Health Dis. 18https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1074-8 (2019).

Yao, H. et al. Coronary lesion complexity in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction: data from the RICO survey. Lipids Health Dis. 20https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01467-z (2021).

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2231–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038 (2018).

Wingo, P. A. et al. (World Health Organization, Geneva, (1994).

Sianos, G. et al. The SYNTAX score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 1, 219–227 (2005).

Sianos, G., Papafaklis, M. I. & Serruys, P. W. Angiographic thrombus burden classification in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Invasive Cardiol. 22, 6B–14B (2010).

Group, T. S. The Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. N Engl. J. Med. 312, 932–936. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198504043121437 (1985).

Porter, T. R. et al. Guidelines for the use of echocardiography as a monitor for therapeutic intervention in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28, 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2014.09.009 (2015).

Pejic, R. N. Familial hypercholesterolemia. Ochsner J. 14, 669–672 (2014).

Kramer, A. I., Trinder, M. & Brunham, L. R. Estimating the prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia in Acute Coronary Syndrome: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 1322–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.06.017 (2019).

Danchin, N. et al. Long-term outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: The French registry of Acute ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction program. J Clin Lipidol 14, 352–360 e356, doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2020.03.008

Farnier, M. et al. Prevalence, risk factor burden, and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction: data from the French RICO survey. J. Clin. Lipidol. 13, 601–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2019.06.005 (2019).

Tscharre, M. et al. Prognostic impact of familial hypercholesterolemia on long-term outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Clin. Lipidol. 13, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2018.09.012 (2019).

deGoma, E. M. et al. Treatment gaps in adults with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in the United States: Data from the CASCADE-FH Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 9, 240–249. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001381 (2016).

Ryzhaya, N. et al. Sex differences in the presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e019286. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019286 (2021).

Agarwala, A. et al. Sex-related differences in premature cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2022.11.009 (2023).

Ikeda, N. et al. Control of hypertension with medication: a comparative analysis of national surveys in 20 countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 92(C), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.121954 (2014).

Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt), El-Zanaty, Associates (Egypt) & ICF International. Egypt Health Issues Survey 2015. (Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt) and ICF International, Cairo, Egypt. (2015).

Dyrbus, K. et al. The prevalence and management of familial hypercholesterolemia in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the Polish tertiary centre: results from the TERCET registry with 19,781 individuals. Atherosclerosis. 288, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.06.899 (2019).

Elbadawi, A. et al. Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Familial Hypercholesteremia. Am J Med 134, 992–1001 e1004, doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.03.013

Gensini, G. G. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 51, 606. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80105-2 (1983).

Auckle, R. et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in Chinese patients with premature ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: prevalence, lipid management and 1-year follow-up. PLoS One. 12, e0186815. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186815 (2017).

Kumar, P., Prasad, S. R., Anand, A., Kumar, R. & Ghosh, S. Prevalence of familial hypercholesterolemia in patients with confirmed premature coronary artery disease in Ranchi, Jharkhand. Egypt. Heart J. 74, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-022-00320-7 (2022).

Rerup, S. A. et al. The prevalence and prognostic importance of possible familial hypercholesterolemia in patients with myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 181, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.08.001 (2016).

Yasuda, T. et al. Coronary lesion morphology and prognosis in young males with myocardial infarction with or without familial hypercholesterolemia. Jpn Circ. J. 65, 247–250. https://doi.org/10.1253/jcj.65.247 (2001).

Stone, G. W. et al. Impact of lesion complexity on peri-procedural adverse events and the benefit of potent intravenous platelet adenosine diphosphate receptor inhibition after percutaneous coronary intervention: core laboratory analysis from 10 854 patients from the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial. Eur. Heart J. 39, 4112–4121. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy562 (2018).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Lesion complexity and outcomes of extended dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 2213–2223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.011 (2017).

Horie, T. [Histopathological findings of coronary arteries in cases with acute coronary syndromes]. J. Cardiol. 33(Suppl 1), 3–8 (1999).

Chen, C. H. et al. Low-density lipoprotein in hypercholesterolemic human plasma induces vascular endothelial cell apoptosis by inhibiting fibroblast growth factor 2 transcription. Circulation. 107, 2102–2108. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000065220.70220.F7 (2003).

Chen, H. H. et al. Electronegative LDLs from familial hypercholesterolemic patients are physicochemically heterogeneous but uniformly proapoptotic. J. Lipid Res. 48, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M500481-JLR200 (2007).

Chan, H. C. et al. Highly electronegative LDL from patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction triggers platelet activation and aggregation. Blood. 122, 3632–3641. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-05-504639 (2013).

Schmidt, K., Noureen, A., Kronenberg, F. & Utermann, G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J. Lipid Res. 57, 1339–1359. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R067314 (2016).

Alonso, R. et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels in familial hypercholesterolemia: an important predictor of cardiovascular disease independent of the type of LDL receptor mutation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, 1982–1989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.063 (2014).

Boffa, M. B. & Koschinsky, M. L. Lipoprotein (a): truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J. Lipid Res. 57, 745–757. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R060582 (2016).

Sankhesara, D. M. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is Associated with Thrombus burden in culprit arteries of younger patients with ST-Segment Elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 148, 98–102. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529600 (2023).

Carvalho, A. C., Colman, R. W. & Lees, R. S. Platelet function in hyperlipoproteinemia. N Engl. J. Med. 290, 434–438. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197402212900805 (1974).

Icli, A. et al. Increased Mean platelet volume in familial hypercholesterolemia. Angiology. 67, 146–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319715579781 (2016).

Sugrue, D. D. et al. Coronary artery disease and haemostatic variables in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Br. Heart J. 53, 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.53.3.265 (1985).

Martinelli, N. et al. Polymorphisms at LDLR locus may be associated with coronary artery disease through modulation of coagulation factor VIII activity and independently from lipid profile. Blood. 116, 5688–5697. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-03-277079 (2010).

Benedek, P. et al. Genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia among survivors of acute coronary syndrome. J. Intern. Med. 284, 674–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12812 (2018).

Wald, D. S., Bangash, F. A. & Bestwick, J. P. Prevalence of DNA-confirmed familial hypercholesterolaemia in young patients with myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26, 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.01.014 (2015).

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not–for–profit sectors. Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KME took part in the conceptualization, analysis of the results, and draft manuscript writing. AA made substantial revisions to the work, revised the data that was gathered, and helped with the conceptualization, format, and design of the study. AHO participated in patient recruiting, clinical evaluation, data collection, and manuscript writing. HHA helped with the work’s idea, design, findings, data interpretation and substantially revised the work. MAFA participated in the work’s design, carried out the statistical analysis, analyzed the results, and finished formatting the final work. All authors have reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical and medical research committee, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University (approval number: 17100752) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants after an explanation of all steps of the study. It was explained to all participants that the collected data was confidential and for scientific research only.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elmaghraby, K.M., Abdel-Galeel, A., Osman, A.H. et al. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep 14, 27098 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77656-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77656-4