Abstract

Structural Path Analysis (SPA) and the Hypothetical Extraction Method (HEM) are both established methods for studying CO2 emissions. However, their combined application to investigate emission linkages in specific sectors, such as construction, is relatively novel. This research integrates SPA and HEM to explore the CO2 emissions linkages within the construction sectors of China and the United States, providing a comprehensive understanding of how these emissions are interlinked. The findings show that construction sector of Untied States and China is the largest production-based CO2 emissions of construction sector in the world, but the consumption-based emissions of construction sector in China contributes 29.81% of total CO2 emissions, compared to 5.63% in the U.S. This suggests that the carbon footprint of the construction sector is a significant consideration, irrespective of whether it is assessed from the standpoint of production or consumption dynamics. Meanwhile, the development of construction sector has driven the electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply sectors to emit a large amount of CO2 emission in both countries. By analyzing the differences in the main emission linkages and pathways of the construction sectors between China and the U.S., this study provides insights for reducing CO2 emissions in the construction sector and assists policymakers in developing future strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To effectively control CO2 emissions from the construction sector, this study analyses the differences in CO2 emissions from the construction sector and their underlying drivers in China and the U.S. As the world’s largest CO2 emitters and key economies, the construction sector in China and the United States account for 6.87% and 4.49% of their respective gross domestic product (GDP)1,2, respectively, and the significant contribution of this sector to the economic growth of both countries has been documented in the literature3,4,5,6. Both countries have invested considerable effort in assessing the energy-saving potential of their building sector, an effort that is vital to reducing CO2 emissions and combating climate change7,8. Moreover, the direct CO2 emissions from the construction industry in both China and the United States rank among the highest within their respective national industrial sectors, and the demand generated by the construction industry significantly contributes to the CO2 emissions of other industries9. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the buildings and construction sector is responsible for nearly 27% of global energy-related CO2 emissions10. The report also warns that without targeted policy interventions, global CO2 emissions from the building sector are projected to increase by approximately 70% by 2050 10.

This study aims to analyse the characteristics of CO2 emissions in the construction sector in China and the U.S. Previous research has investigated the trends and driving factors of CO2 emissions in the construction sector11,12. These studies have provided valuable insights into reducing CO2 emissions in the construction sector. However, most of these studies have focused on the production aspects of specific sectors, neglecting the industrial linkages between various sectors within the entire economic system and their external impacts on CO2 emissions13. This paper not only analyses CO2 emissions from the perspectives of production-based and consumption-based CO2 emissions, but also conducts an examination of other types of CO2 emissions linkages. The construction sector plays a crucial role in connecting the downstream supply chain in economic activities, consuming a significant number of intermediate products and services, and thereby promoting economic development. These industrial linkages not only directly affect the CO2 emissions of the construction sector but also indirectly influence the consumption-based CO2 emissions of the construction sector. This paper uses the SPA and HEM to analyse the CO2 emission linkages between the construction sector and other sectors in China and the U.S. This research also provides information on how to reduce CO2 emissions in the construction sector by analysing the differences between the two. Considering that the construction sector in China and in U.S. is the largest sector in terms of CO2 emissions, the analysis of these differences will benefit policymakers in formulating relevant policies.

Literature review

The input‒output model is an economic model based on input‒output tables that can analyse complex industrial linkages between sectors with limited data14. This model is often considered an effective tool for evaluating the impact of socioeconomic activities on energy consumption and CO2 emissions15,16. This model considers not only the internal linkages but also the characteristics of socioeconomic changes17,18. However, there are certain limitations in relying solely on direct or full consumption coefficients for analysis19,20,21. The Hypothetical Extraction Method (HEM) is a method based on the input‒output model, which calculates overall, forward, and backward linkages by comparing the changes in the output value of a national economic system before and after the extraction of a sector22.Ali, et al.23 applied hypothetical extraction method (HEM) to analyse the construction sector in three countries, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, exploring its impact on other sectors in the economic system by removing it. The results showed that in these three economies, the construction sector had strong backward linkages and pull effects, while forward linkages and push effects were relatively weak. HEM does not fully consider the internal effect linkages and mixed-effect linkages, whereas traditional input‒output models are commonly used for economic analysis. Sánchez-Chóliz and Duarte19 proposed a modified hypothetical extraction method (MHEM) and combined it with vertical integration consumption, making it suitable for research in environmental economics and other fields.

Li, et al.24 applied the MHEM to analyse the energy consumption of various industrial sectors in China from the perspectives of mixed effects, internal effects, net forward linkages, and net backward linkages. Sajid, et al.25 used the MHEM to estimate the CO2 emission linkages between the mining sector and other sectors within ten major economies. The results showed that all countries had net CO2 emission exports in other industrial sectors. Wang, et al.26 used the MHEM to analyse China’s CO2 emissions and found that the energy sector had the most direct CO2 emissions, while the technology, construction, and service sectors were the main destinations for CO2 emissions. MHEM can quantify resource consumption and CO2 emission linkages between industrial sectors more accurately by considering the direct and indirect resource consumption or CO2 emissions required to meet final demand24,27,28. Zhang, et al.29 employed the MHEM to conduct a CO2 emission linkages analysis within the construction industry. However, the study only identified key sectors and lacked an analysis of the critical pathways.

Based on these studies, it is generally believed that certain sectors, such as the construction sector, are the destinations of carbon flows, while industrial sectors such as mining are the sources. However, previous studies have mainly investigated the internal situation of industrial sectors through linkage analysis without delving into the flow of CO2 emissions between sectors or providing an analytical path for influencing factors. Therefore, the introduction of the structural path analysis (SPA) method helps to address these issues30,31. SPA method enables the tracing of carbon flows throughout the entire supply chain, identifying critical sectors and key supply chains. This facilitates an understanding of the role of final demand in driving CO2 emissions. In past research, SPA has been used by many researchers for analysis. For example, Wu, et al.32 employed the SPA method to analyze the CH4 emissions associated with agricultural supply in China, while identifying critical sectors and pathways. They proposed measures to mitigate CH4 emissions from both production and consumption perspectives. Similarly, Mitoma, et al.33 utilized the SPA approach to investigate the mortality rates associated with PM2.5 emissions in the electricity supply sector. They found that domestic final demand is a primary driver of PM2.5-related deaths in India, and that the final demand sectors of Middle Eastern, American, and Chinese countries indirectly contribute to PM2.5-related mortality in India through the rice export supply chain. Wang, et al.34 analysed the CO2 emission paths and transfer characteristics in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region using the SPA method. Zhang, et al.35 used SPA to analyse the energy flow and transfer characteristics between different industrial sectors in China. These studies have shown that the SPA method is effective in identifying important supply chains, channels, and transfer mechanisms for pollutants in economic systems.

This research employs the Modified Hypothetical Extraction Method and Structural Path Analysis to investigate CO2 emission linkages and transfer mechanisms within the construction sectors of China and the United States. Utilizing the 2018 OECD input-output tables alongside CO2 emission data, this study applies SPA to conduct a comparative analysis of CO2 emission linkages between the two countries, aiming to uncover underlying causes and enhance the management and control of CO2 emissions within the construction industry. By analyzing CO2 emissions from both consumption and production perspectives, the research assesses the linkage effects and identifies key pathways impacting CO2 emissions in the construction sectors of both nations. This dual perspective aids in a comprehensive understanding of CO2 dynamics, providing crucial insights for developing targeted CO2 emission management strategies. Furthermore, the identification of specific sources and destinations of CO2 emissions related to the construction sector, as well as mapping the flow of CO2 through the economic systems of China and the United States, establishes a solid foundation for formulating effective strategies to control CO2 emissions. This approach not only enhances the specificity of the emission control strategies but also contributes to global efforts in reducing the environmental impact of the construction industry.

Methods and data

Input‒output model

The input‒output model analyses economic relationships and material exchange activities between different industries within a national economic system36. The model is shown as follows:

\(\:X\) is the vector of total output, \(\:Y\) represents the vector of total final demand, \(\:A\) is the direct consumption coefficient matrix, whose elements A= (\(\:{a}_{ij}\)) and \(\:{a}_{ij}\) represent the direct consumption coefficient of industrial sector \(\:j\) for industrial sector \(\:i\) in the economy system, and \(\:{a}_{ij}={x}_{ij}/{X}_{j}\).

Equation (1) can be transformed as follows:

where \(\:I\:\) is the identity matrix and \({(I - A)^{ - 1}}\) is the Leontief inverse matrix, which reflects the change in the total direct and indirect amount of each product when the final demand of other industrial sectors increases.

CO2 emissions are calculated as follows:

\(\:F\:\)represents the total amount of CO2 emissions, which includes the direct and indirect CO2 emissions during the production of the industrial sector. \(\:q\) is the diagonal matrix composed of the CO2 emission intensity of each industrial sector.

Hypothetical extraction method

The hypothetical extraction method (HEM) is based on the input‒output model, and we assume that the entire economic system excludes one industrial sector. By comparing the changes in the entire economic system before and after the removal of the industrial sector, we can analyse the importance of this industrial sector and its linkages with other industrial sectors. The entire economic system \(\:X\) is divided into an industrial sector \(\:a\) and an industrial sector \(\:b\)35.

\(\:L\) is Leontief inverse matrix.

Assuming that industrial sector \(\:a\) is removed from the entire economic system, \(\:a\) and \(\:b\) will not engage in economic exchange, and the economic system can be represented as:

The changes in the economic system can be represented as follows:

\(\:D\) represents the product of the Leontief inverse matrix of an sector after removing it from the entire economic system and the diagonal matrix of CO2 emission intensity.

The total linkage emission (\(\:TLE\)) is:

The backward linkage emission (\(\:BLE\)) is:

The forward linkage emission (\(\:FLE\)) is:

\(\:\partial\:\) is the identity vector,\(\:\:\partial\:=(\text{1,1},…,1)\), and Eq. (7) (8) and (9) satisfy the following relationship:

When the CO2 emission linkage index of an industrial sector is greater than 1, the influence of this industrial sector on the entire economic system’s CO2 emissions is greater than that of other industrial sectors.

Modified hypothetical extraction method

The effects of CO2 emission linkages according to the modified hypothetical extraction method (MHEM) can be divided into internal effect linkage CO2emission (\(\:IEE\)), mixed-effect linkage CO2 emission (\(\:MEE\)), net backward CO2 linkage emission (\(\:NBLE\)), and net forward linkage CO2 emission (\(\:NFLE\))37.

\(\:IEE\) refers to internal effect linkage CO2 emissions, which are CO2 emitted by industrial sectors when they consume their own products within their own material exchange.

Mixed-effect linkage CO2 emissions (\(\:MEE\)) represent the CO2 emissions caused by the consumption of output from industrial sector \(\:a\:\) by other industrial sectors \(\:b\:\) for production and then the consumption of products from industrial sector \(\:b\:\) by industrial sector \(\:a\), resulting in CO2 emissions. This approach has both forward and backward linkage characteristics.

Net forward linkage CO2 emission (\(\:NFLE\)) refers to the CO2 emissions generated by the consumption of output from industrial sector \(\:a\) by industrial sector \(\:b\). This emission does not reverse back to industrial sector \(\:a\) with the output of products, and \(\:NFLE\) reflects the net export of CO2 by industrial sector \(\:a\).

Net backward linkage CO2 emission (\(\:NBLE\)) refers to the CO2 emissions generated when sector \(\:a\) purchases products from sector \(\:b\:\)to meet final demand. It reflects the net import of CO2 emissions by industrial sector \(\:a\).

Equations (13) and (14) refer to the total net forward and net backward transfers of CO2 emissions, and by breaking them down, it is possible to clearly demonstrate the specific transfer direction of CO2 emissions between various industries. Assuming that \(\:c\) is a subsector within the industrial sector \(\:b\), we can decompose \(\:a\)the net forward linkage CO2 emission and net backward linkage CO2 emission as follows:

\(\:{NFLE}_{a\to\:c}\) are the CO2 emissions exported from \(\:a\), which are generated in \(\:a\) to meet the final demand of \(\:c\).

\(\:{NBLE}_{c\to\:a}\) are the CO2 emissions imported from \(\:a\), which are generated in \(\:c\:\)to meet the final demand from \(\:a\).

Production-based CO2 emissions (\(\:PBE\)) refer to the CO2 directly emitted by a sector during its economic activities. Consumption-based CO2 emissions (\(\:CBE\)) refer to the total CO2 emissions from all the industrial groups involved in producing the final product, including not only the CO2 emitted by the sector’s own production but also the CO2 emitted by other industrial groups in its supply chain. The relationships between CO2 emission linkages and \(\:PBE\) and \(\:CBE\) can be presented as follows24:

The relationships between total CO2 emissions (\(\:TE\)) and \(\:PBE\) and \(\:CBE\) can be described as follows:

\(\:{PBE}_{a}\) and \(\:{CBE}_{a}\) refer to \(\:PBE\) and \(\:CBE\), respectively, from sector \(\:a\). \(\:{PBE}_{b}\) and \(\:{CBE}_{b}\) refer to \(\:PBE\) and \(\:CBE\), respectively, from sector \(\:b\).

The net transferred CO2 emissions (\(\:NTE\)) can be presented as follows:

When the NTE is less than 0, the sector net imports CO2 emissions from the system. When the NTE is greater than 0, the sector net exports CO2 emissions to the system.

The total consumption-based CO2 emissions in the economic system are equal to the total production-based CO2 emissions, implying that the total production-based CO2 emissions flowing through the supply chains in the system are equal to the sum of direct and indirect CO2 emissions required by each sector to meet final demand. If the consumption-based CO2 emissions of an sector are greater than its production-based CO2 emissions, this means that the sum of direct and indirect CO2 emissions needed to meet the final demand of that sector is greater than the production-based CO2 emissions when the sector is producing. This net import sector requires other industries to provide for its production and exchange activities and is a recipient of other industries in the economic system; the difference between consumption-based and production-based CO2 emissions is the net import of that sector. Conversely, if the production-based CO2 emissions of a sector are greater than its consumption-based CO2 emissions, the direct and indirect CO2 emissions needed to meet the final demand of that sector are less than the production-based CO2 emissions. This net export sector exports to other industries and acts as a supplier in the economic system; the difference between production-based and consumption-based CO2 emissions is the net output of that sector.

Structural path analysis

Structural path analysis (SPA) is a widely used tool in environmental economics. It breaks down an economic body’s pollutant emissions or resource consumption into various paths within its production system. These paths are then organized based on direct emissions, helping to identify key factors influencing emissions or consumption38,39. In this paper, the SPA method is used to determine how and through which channels CO2 emissions linked to the supply chain are transmitted and distributed. Examining the transmission path of CO2 emissions from different perspectives will aid in establishing a comprehensive understanding of the interaction between construction and other sectors in the economy. The Leontief inverse matrix can be approximated by considering the Taylor series40:

CO2 emissions are calculated as follows:

As demonstrated in (22), the total CO2 emissions in the economic system are deconstructed layer by layer in the production process, with this procedure persisting through an infinite series of exponents. \(\:{qA}^{n}Y\) symbolizes the CO2 generated by the nth production layer.

To determine the key paths for industrial sector \(\:a\) in the supply chain from the \(\:NFLE\) perspective, we must analyse the CO2 emissions generated by the final demand of other economic departments in each production layer except for sector \(\:a\). Based on (22), these emissions can be expressed as:

To determine the key paths for industrial sector \(\:a\) in the supply chain from the \(\:NBLE\) perspective and to analyse the emissions produced by other industrial sectors in each production layer excluding the target sector \(\:a\), based on (22), these emissions can be expressed as:

Data

The data used in this paper are from the OECD’s 2018 input‒output tables and CO2 emission intensity data for China and the United States9. The OECD’s input‒output tables consist of a set of 45 industrial sectors and 8 final consumption sectors, which include final consumption expenditure of households (HFCE), final consumption expenditure of non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH), final consumption expenditure of general government (GGFC), gross fixed capital formation (GFCE), changes in inventories and valuables (INVNT), direct purchases abroad by residents (DPABR), and export (EXPO). The framework of this study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Empirical analysis

Based on OECD data, this paper conducts a horizontal analysis of CO2 emissions from the construction sector in China and the United States, focusing on consumption-based CO2 emissions, production-based CO2 emissions, CO2 emission linkages, and net transferred CO2 emissions.

Production-based CO2 emissions and consumption-based CO2 emissions

Production-Based CO2 Emissions reflect a sector’s direct CO2 emissions. Consumption-based CO2 emissions refers to the total CO2 emissions produced by all the industrial sectors involved in the production of a final product. According to Eq. (17) and referring to Table 1, the OECD-ICIO data reveals that the total CBE in the United States exceed total PBE, contrasting with China where total PBE is higher. This suggests the U.S. imports more CO2 emissions than it exports, whereas China exports more. Moreover, the construction sector in both nations is a net CO2 emissions importer.

In the construction sectors of both the U.S. and China, most PBE is sourced domestically, as illustrated in the Fig. 2. The proportion of CBE sourced domestically in the U.S. construction sector is 71.05%, while in China, it’s 93.47%. This suggests a slight difference in the consumption of foreign products between the two countries, with the U.S. having a higher demand for foreign products compared to China, where most construction consumption is met by domestic supply chains.

Table 2 illustrate that the construction sectors of China and the United States respectively rank first and second in the global construction sector’s production-based CO2 emissions. As shown in Tables 1 and 3, the largest production-based emitting industries in both the United States and China are Electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (S23), accounting for 49.81% and 52.61% of total emissions, respectively, while the construction sector’s CO2 emissions account for only 3.10% and 1.51%, respectively. China, as one of the world’s largest developing countries with a large population and rapid economic growth, has a substantial energy demand. With a coal-dominated energy structure, the generation of electricity requires the consumption of large amounts of coal, which contributes to higher CO2 emissions. The United States, as one of the world’s largest developed countries, has a high level of economic development and significant energy demands. Its energy structure is predominantly composed of fossil fuels, including oil, natural gas, and coal, which also result in substantial CO2 emissions when burned41,42.

Consequently, the PBE of the S23 sector constitutes a larger portion of the total emissions in both countries. The direct energy demands of the construction sector are relatively low in both countries43, resulting in a lower PBE proportion for this sector.

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the composition of PBE in China and the United States from the perspective of the final demand category. In the United States, HFCE makes the largest contribution to PBE, accounting for 76.74%. In contrast, China’s PBE is significantly influenced by HFCE, GGFC, and EXPO. This discrepancy reflects the differences in the economic structures of the two countries. In the United States, residential consumption plays a significant role in driving economic development, resulting in a greater proportion of PBE generated from residential consumption activities. However, in China, economic development is driven not only by HFCE but also significantly by GGFC and EXPO, with these three categories collectively driving the majority of PBE in China44,45.

Although the proportion of PBE from HFCE in the United States is higher, its total volume is still lower than that of China, primarily due to China’s much larger population. In the construction sector, the PBE in both China and the United States are primarily driven by GFCFs, with emissions of 107.41 million tons and 115.96 million tons, respectively. The rapid development of the construction sector also relies on the direct consumption of fossil fuels, leading to CO2 emissions from production activities.

Therefore, from the perspective of PBE, to reduce the overall CO2 emissions of the economic system, both China and the United States need to enhance the green consumption awareness of residents. In particular, China needs to research and implement relevant green consumption policies for government consumption and exports. Additionally, when formulating CO2 emission management measures for the construction sector, both countries should first consider their respective energy structures, reduce their dependence on fossil fuels, and increase their energy efficiency and the proportion of renewable energy use.

According to Eq. (18), as Shown in Table 4, in the construction sector of the United States and China, the CBEs were 307.52 Mt and 3012.73 Mt, respectively, ranking high among all industries in their respective countries (fourth in the United States and first in China).

The data for 2018 reveal significant differences in the economic and environmental impacts of the construction sector between the United States and China. The CBE of the construction sector represents 7.18% of total emissions in the United States, a figure that jumps significantly to 33.15% in China. These statistics underscore the differing roles of the construction sector in the economic and environmental contexts of the two countries.

The disparity in the CBE’s contribution to total emissions is primarily due to the differences in economic structure between the two countries. China’s economic development has been more reliant on the construction sector, especially in the past decade, as rapid urbanization has driven the sector’s growth. This has led to a massive demand for high-energy, high-emission building materials such as steel, cement, and glass, resulting in substantial CBE. In contrast, the construction sector in the United States has a lower demand for these high-energy and high-emission materials. Moreover, in the United States, construction management not only focuses on the direct CO2 emissions of construction activities but also places emphasis on the entire lifecycle of buildings. There are strict limitations on the use of high-energy materials, which helps to reduce the overall CO2 footprint of the construction sector46,47. For example, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) requires a reduction in the use of metal materials in its relevant construction guidelines and provides corresponding evaluation tools, such as the AIA-CLF Embodied Carbon Toolkit, to help architects assess the embodied CO2 emissions in construction activities. This toolkit aims to help architects and designers understand and reduce CO2 emissions generated by building materials and construction processes, thereby promoting more sustainable construction practices. By using such tools, architects can make more environmentally friendly choices and reduce the overall carbon footprint of the construction sector48.

Therefore, the differing proportions of CBE in the total emissions can be attributed to the economic structure, urbanization processes, and policy differences between the two countries. By comparing the two, we find that China can establishing policies that restrict the use of high-energy, high-emission materials in the construction sector. Simultaneously, slight improvements can be made to the existing green consumption policies related to government procurement and exports. Historically, green consumption policies have primarily focused on direct carbon emissions during the production process of products; however, current attention can be more directed towards the life-cycle carbon emissions of products12,49. Finally, while ensuring economic development, China can seek new economic growth points to reduce its dependency on the construction sector.

CO2 emissions linkages

Net forward linkage CO2 emission reflect the net export of CO2 emissions from a particular sector. Net backward linkage CO2 emission reflect the net export of CO2 emissions from a particular sector. Internal effect emission refers to the direct and indirect CO2 emissions generated by a sector using its own products to meet its final demand. It reflects the CO2 emissions produced by the industry itself in the processes of production, sales, and usage. Mixed linkage emissions refers to the CO2 emissions generated in the process where a target industry sells its products to other industries as intermediate inputs and then buys back the products from those industries to meet its own final demand.

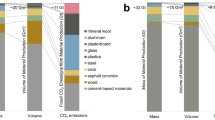

According to Eq. (16), as shown in Fig. 5, the construction sector, which is typically situated at the downstream end of the consumption chain, exhibits significant interdependence with upstream sectors. Its final demand has a ‘pulling effect’ on the CO2 emissions of these other sectors. In China, the NBLE for the construction sector is 2897.67 Mt, substantially higher than the 219.61 Mt observed in the United States. This substantial discrepancy can be attributed to factors detailed in the previous chapter: the substantial demand from China’s final consumption sector for the construction sector, coupled with the construction sector’s high demand for high-energy-consuming and high-emission materials from upstream enterprises. In contrast, the United States imposes greater restrictions on the use of such materials by its construction sector. Additionally, the majority of houses in the United States employ wooden frame construction, despite the substantial use of concrete. In contrast, Chinese construction is almost entirely steel-reinforced concrete. This also contributes to the NBLE differences in the construction sectors between China and the United States.

According to Eq. (15), the NFLEs for the construction sectors in both the United States and China are relatively low, at 19.76 Mt and 0.90 Mt, respectively. Sectors with higher NFLE are predominantly found in the energy and manufacturing sectors. This is because the construction sector, which is typically a downstream enterprise, experiences less demand from other sectors, resulting in lower NFLE levels for the construction sectors in both China and the United States. The energy and manufacturing sectors, usually upstream, produce goods that are widely consumed by other sectors, thereby generating significant CO2 emissions12,46.

In both the United States and China, sectors with higher MEEs and IEEs are primarily concentrated in the energy and manufacturing sectors. The IEEs for the construction were 87.34 Mt and 114.97 Mt, respectively, while the MEEs were 0.31 Mt and 0.09 Mt, respectively. The demand from the final consumption sector for the construction sector led to the accumulation of related CO2 emissions within the construction sector. Furthermore, the energy and manufacturing sectors rely heavily on products within their own industries, that is, the internal consumption of their sectors, which also contributes to higher MEE and IEE emissions from these sectors.

According to the result of IEE and PBE, the proportion of IEE in the PBE for the S23 in the United States is higher than that of the IEE in the PBE for the S23 in China. It is indicated that the auxiliary power consumption efficiency of the S23 in the United States is lower than that of China, primarily because China’s power plants are newer and more efficient50,51,52,53. However, the CO2 emission coefficient of the S23 in the United States is lower than that of China, mainly due to differences in energy consumption patterns: the United States uses more natural gas, while China relies more heavily on coal52,54. Meanwhile, the auxiliary power consumption efficiency of coal-fired power plants is higher than that of natural gas turbine power plants52,53.

According to Eq. (20), when the NTE is less than 0, it indicates that the CO2 emissions based on production are less than those based on consumption, meaning that CO2 emissions from other industrial sectors in the economic system have been transferred to this sector, making it a net emissions importer. Conversely, when the NTE is greater than 0, the CO2 emissions based on production exceed those based on consumption, implying that CO2 emissions from this sector have been transferred to other industrial sectors in the economic system. In this case, the sector is a net emissions exporter. For sectors with negative NTEs, it is important to consider the pulling effect of their final demand on the CO2 emissions of other sectors in the economic system.

According to Fig. 6, the largest CO2 emissions exporting sectors in both the United States and China are Electricity, Gas, Steam, and Air Conditioning Supply (S23), with emissions of 1025.10Mt and 3233.70 Mt, respectively. The net transferred CO2 emissions for the construction sector in China and the United States are − 2896.77 Mt and − 199.84 Mt, respectively. This indicates that the final demand of the construction sectors in both countries has led to a significant consumption of intermediate products from upstream sectors, resulting in substantial CO2 emissions in those sectors. Consequently, the potential and focus for reducing CO2 emissions are concentrated on the CO2 emissions associated with the consumption of the construction sector. Particularly in China, due to the larger amount of transfer, the potential for emission reduction in its construction sector is even greater. Therefore, improving the construction model of China’s construction sector and encouraging consumers to choose green buildings is necessary for achieving low-carbon development in the entire economic system. For example, policy measures that can be taken to encourage the low-carbon development of the construction sector include green building standards, incentives for using sustainable materials, or regulations that restrict high-emission construction practices55.

When decomposing the NFLE and NBLE of the construction sector from an international perspective, as Table 5 shows, the majority of NBLE in the US construction sector comes from China and Mexico. However, China’s situation is slightly different, with Russia and South Korea being the main contributors to the NBLE in China’s construction sector. The primary reason for this is the differing trade structures between the US and China. Table 6 illustrates that the total volume of NFLE from international sources within the construction sector is very low, suggesting that the influence of foreign NFLE on total NFLE is nearly negligible.

To further trace the origins of NBLE from international sources in the construction sectors of both China and the United States, it has been found that the primary source of NBLE in these sectors is the electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (S23) sector. The construction materials purchased by the construction sectors in both countries consume significant amounts of electricity during production, in addition to directly using fossil energy sources. Consequently, policymakers in China and the United States should consider imposing carbon tariffs on these products. When formulating policies, it is essential not only to consider the direct CO2 emissions from the production process but also to take into account the entire lifecycle CO2 emissions of the products.

Decomposing the NBLE at the sector level from a domestic perspective offers insights into how the construction sectors in the United States and China drive CO2 emissions in other sectors. Figure 7 illustrates that the top three sources of NBLE for the construction sectors in both countries include the electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (S23) sector and the other non-metallic mineral products (S14) sector, with NBLE related to S23 comprising more than 30% of the total NBLE. These sectors are significant sources of CO2 emissions, driven by the development of construction sectors in both countries. Particularly in the context of China’s rapid modernization, the construction sector not only directly consumes large amounts of electricity and non-metallic materials (such as talc, cement, etc.) to support its production activities but also relies on materials from other sectors, the production processes of which also consume electricity and non-metallic raw materials.

However, there are some differences between the construction sectors in the U.S. and those in China. During the construction process, the Chinese construction sector consumes more metal materials, leading to considerable CO2 emissions from the Basic Metals (S15) sector in China. In contrast, the greater reliance of the United States on land transport due to economic development results in the final demand of the construction sector pulling CO2 emissions from the Land Transport and Transport via Pipelines (S27) sector, making it the second-largest source of NBLE for the construction sector in the United States.

When decomposing the NFLE to the sector level domestically, it becomes evident which sectors primarily stimulate CO2 emissions from the construction sector. In almost all countries, real estate activities (S37) and public administration and defense and compulsory social security (S40) are significant demanders of the construction sector’s services. Consequently, for the construction sectors in the United States and China, these two sectors are the main stimulators of NFLEs. The third-largest source of NFLEs for the construction sector in the United States is the Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles (S26) sector, while in China, it is the Education (S41) sector. This discrepancy is due to China’s large population and substantial demand for education versus the greater demand for social retail and car-related services in the United States. As a source of CO2 emissions, the low-carbon development of the construction sector is crucial in shaping greener downstream sectors.

Structural path analysis of CO2 emissions in construction sector

In the preceding section, the MHEM was applied to assess the construction sector, focusing on its influence on the CO2 emissions of both upstream and downstream sectors across various industrial stages. Understanding the transmission routes of carbon dioxide emissions within the construction sector is crucial for formulating emission reduction strategies, promoting the green transformation of the sector, and achieving national emission reduction targets. Therefore, in this chapter, we employ SPA to explore the transmission routes of CO2 emissions within the construction sector. Specifically, we will approach this analysis from two perspectives. First, by treating the construction sectors of China and the United States as producers, we will examine the distribution and impact pathways of CO2 emissions in the construction sector’s production chain from the perspective of the NFLE. On the other hand, considering the construction sectors of both countries as consumers, we investigate the distribution and impact pathways of CO2 emissions in the construction sector’s consumption chain from the perspective of NBLE. Through structural path analysis, our aim is to identify the key pathways influencing the CO2 emissions of the construction sectors in China and the United States.

Structural path analysis in different layers

According to Eq. (22) to (28), Table 7 displays the total CO2 emissions and their proportions at each layer for the NFLE and NBLE in the construction sector in China and the United States. The second layer represents the direct supply path, while the third layer and above signify indirect supply paths. In both China and the United States, the CO2 emissions from the second to fourth layers of the NBLE and NFLE constitute the vast majority (all exceeding 80%), indicating that efficient CO2 emission management strategies need to focus only on these three layers. From the perspective of the NFLE, in both China and the United States, the proportion of indirect paths in the second layer exceeds 50% (53.40% in China and 73.32% in the United States), suggesting that the net export of CO2 emissions in the construction sector is primarily transferred to other sectors through direct supply paths. From the perspective of NBLE, both direct and indirect supply paths significantly contribute to emissions. Therefore, from the perspective of NBLE, effective CO2 management strategies need to consider CO2 emissions in both single-layer and multilayer supply chains.

Structural path analysis of net backward linkage CO2 emission from construction in the United States and China

When the construction sector serves as the final link in the supply chain, structural path analysis of the NBLE can reveal how other sectors transfer CO2 to the construction sector.

According to Eq. (26) to (28), Table 8 shows that the top 10 NBLE pathways for the construction sector in the United States are secondary and tertiary pathways, accounting for 26.84% of the total NBLE, and all sources are domestic. The sectors with the most significant influence on NBLE are electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (S23), Other non-metallic mineral products (S14); and land transport and transport via pipelines (S27). As shown in Fig. 8, approximately 76% of CO2 emissions from S23 indirectly transferred to the construction sector. For S14 and S27, the direct supply pathway proportions are 89% and 65%, respectively. This result is driven by the American lifestyle and production activities, high fossil fuel consumption, and the limited use of new energy vehicles in 2018. Products such as limestone, talc, and cement, which are produced by the other S14 sectors, are the main demand for construction and are less needed in other sectors.

In China, the construction sector’s top ten NBLE pathways, including secondary, tertiary, and quaternary pathways, make up 46.50% of the total NBLE, and all sources are domestic. The three sectors with the most significant impacts are electricity, gas, steam, air conditioning supply (S23), basic metals (S15), and other non-metallic mineral products (S14). As shown in Fig. 8, for the construction sector, 83% of CO2 emissions from S23 and 79% from S15 are transferred through indirect and direct supply pathways, respectively. The reasons are similar to those in the U.S. However, S14 is unique since CO2 is equally transferred through direct and indirect supply pathways. This is mainly because products from S15, such as steel bars, are directly bought by the construction sector, and other products consuming S15 products, such as light bulbs and other metal products, are also purchased by the construction sector.

This chapter reveals the top 10 NBLE pathways of the construction sector in the U.S. and China, guiding policymakers on emission reduction strategies. It is crucial to pay extra attention to S23, the primary CO2 source, and consider both its direct use in construction and its consumption by related sectors. Furthermore, in the United States, the top 10 NBLE pathways account for a relatively minor proportion of the total NBLE, with all sources being domestic, thereby highlighting the complexity of carbon emissions within the construction industry’s supply chain. The development of effective emission reduction policies necessitates an understanding of the inter relationships within the supply chain.

Structural path analysis of net forwards linkage emission from construction in the United States and China

According to Eq. (23) to (25), Table 9 lists the top 10 pathways that lead to the highest NFLEs in the construction sectors of both the U.S. and China, showing how CO2 from construction reaches consumers through the supply chain.

In the U.S., the main NFLE pathways in the construction sector are secondary and tertiary, and the secondary pathways account for 72.22% of the total emissions. In China, the top ten pathways are all secondary, accounting for 54.59% of emissions. This indicates that both countries primarily export CO2 from construction through direct supply pathways. The three largest pathways for both are real estate activities (S37), public administration and defence, compulsory social security (S40), and education (S41), which are driven by their direct procurement from construction. CO2 often moves directly from construction to sectors S27 and S40 due to fewer intermediate links.

As shown in Fig. 9, the third-largest source of NFLEs for the U.S. construction sector is S26, with 75% of its CO2 exports to S26 occurring indirectly. This is because the retail and automotive repair industries usually purchase goods from other sectors, such as agriculture or consumer goods, which need construction services, such as building factories. Therefore, S26 does not have a high direct need for construction products or services.

In summary, alongside the strategies outlined in Sect. 4 to mitigate the NFLE of the construction sector in the U.S. and China, the U.S. must also consider the transfer of CO2 to the downstream sector S26 through indirect supply pathways from S23 when devising pertinent green building policies.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper begins by conducting an in-depth study of PBE and CBE in the construction sectors of China and the United States under the MHEM. Although the proportion of CO2 emissions from the construction sector based on production is not high in both China and the United States, from the perspective of consumption, the levels of CBE in the construction sectors of both countries are relatively high. Therefore, the development of the construction sector leads to a significant amount of indirect CO2 emissions that cannot be ignored. This fact necessitates that policymakers consider the consumption-based CO2 emissions of the construction sector when formulating low-carbon policies.

This research analyses the CO2 emission linkages (NBLE, NFLE, IEE, and MEE) and the NTE between the construction sector and its upstream and downstream sectors. By identifying data related to CO2 emission linkages, policymakers can better understand the drivers of emissions and develop targeted policies to reduce the carbon footprint. The results indicate that the NBLE of the construction sectors in both China and the United States significantly contributes to the total CBE, with both industries being net importers of CO2 emissions. However, the net CO2 imports of the Chinese construction sector far exceed those of the United States, primarily due to its greater demand for high-energy-consuming products. Additionally, the structural characteristics of Chinese and American constructions differ, with Chinese construction predominantly using steel and concrete, while wooden structures are more common in the United States. The American construction sector has more stringent policies on material use and provides tools for assessing the CO2 emissions of construction production activities. Therefore, China can reduce the use of high-energy-consuming and high-emission building materials, and offer assessment tools to professionals in the construction sector to plan for the CO2 emissions of construction production activities in advance.

Further decomposition of the NBLE structure revealed that the electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (S23) sector contributes significantly to the NBLE of the construction sector. According to the results, China’s S23 is more dependent on fossil fuels, which is one of the reasons for China’s construction sector having a higher NBLE than that of the United States. Although the residential construction structure in the United States tends to use fewer high-energy-consuming materials, the production and transportation of these materials still contribute substantially to CO2 emissions from the S27.

Therefore, to reduce the NBLE of the construction sector in both China and the United States, it is crucial to optimize their respective energy structures and actively promote the use of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power as ideal alternatives to fossil fuels. Additionally, governments can encourage the research, development, and production of renewable energy through policy-making, subsidies, and loans while also strengthening the construction of energy infrastructure to improve the transmission and distribution efficiency of renewable energy.

This study has limitation, as it primarily focuses on China and the United States, and its findings may not be fully applicable to other countries. Future research could expand the scope to include a broader range of countries and regions, thereby enhancing the generalizability and applicability of the findings. Meanwhile, it could further investigate the CO2 emission characteristics of various materials and technologies within the construction industry to identify more effective mitigation strategies. Additionally, it could examine the efficacy of policy interventions by analyzing the specific impacts of various policy measures on CO2 emissions in the construction sector. Lastly, considering the global impact of climate change, future research should emphasize international collaboration to collectively seek global solutions for reducing CO2 emissions in the construction industry.

China and the United States are the world’s largest CO2 emitters, and the construction sector is one of the largest sources of CO2 emissions. To reduce the impact of CO2 emissions from the construction sector, this study, based on previous research, analyses the CO2 emissions of construction sectors in China and the United States using the structural path analysis (MHEM-SPA) method and explores the current status and influencing factors of CO2 emissions in construction sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the OECD repository,https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/inter-country-input-output-tables.html.

Abbreviations

- BLE:

-

Backward linkage CO2 emission

- FLE:

-

Forward linkage CO2 emission

- IEE:

-

Internal effect linkage CO2 emission

- MEE:

-

Mixed-effect linkage CO2 emission

- NBLE:

-

Net backward CO2 linkage emission

- NFLE:

-

Net forward linkage CO2 emission

- NTE:

-

Net transferred CO2 emission

- PBE:

-

Production-based CO2 emission

- TLE:

-

Total linkage CO2 emission

- A:

-

Direct consumption coefficient

- F:

-

Total amount of CO2 emission

- I:

-

Identity matrix

- L:

-

Leontief inverse matrix

- X:

-

Vector of total output

- Y:

-

Vector of total final demand

- q:

-

CO2 emission coefficient

- \(\partial\) :

-

Identity vector

References

NBSPRC. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development 2018. (2019).

BEA. Gross Domestic Product by Industry: Fourth Quarter and Annual 2018. (2019).

Bhattacharyya, A. & Hastak, M. Construction Research Congress (CRC) on Project Management and Delivery, Contracts, and Design and Materials. 254–262 (2022).

Luo, X., Liu, C. & Zhao, H. Driving factors and emission reduction scenarios analysis of CO2 emissions in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and surrounding cities based on LMDI and system dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 870, 161966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161966 (2023).

Liang, W. & Yang, M. Urbanization, economic growth and environmental pollution: evidence from China. Sustainable Computing-Informatics Syst. 21, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2018.11.007 (2019).

OECD. A Territorial Approach to Climate Action and Resilience. (2023).

Hu, S., Zhang, Y., Yang, Z. Y., Yan, D. & Jiang, Y. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China’s building sector-modelling and data. Build. Simul. 15, 1899–1921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12273-022-0912-1 (2022).

Lu, Y. J., Zhu, X. Y. & Cui, Q. B. Effectiveness and equity implications of carbon policies in the United States construction industry. Build. Environ. 49, 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2011.10.002 (2012).

OECD. OECD, (2021).

IEA. Roadmap for Energy-Efficient Buildings and Construction in ASEAN. (2022).

Guo, Q. B., Wang, Y. & Dong, X. B. Effects of smart city construction on energy saving and CO2emission reduction: evidence from China. Appl. Energy. 313 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118879 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Green construction for low-carbon cities: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21, 1627–1657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01544-4 (2023).

Jiang, T. Y., Li, S. Q., Yu, Y. & Peng, Y. F. Energy-related carbon emissions and structural emissions reduction of China’s construction industry: the perspective of input-output analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 39515–39527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17604-1 (2022).

Liu, L. R. et al. Input-output modeling analysis with a detailed disaggregation of energy sectors for climate change policy-making: a case study of Saskatchewan, Canada. Renew. Energy. 151, 1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.11.136 (2020).

Agez, M. et al. Hybridization of complete PLCA and MRIO databases for a comprehensive product system coverage. J. Ind. Ecol. 24, 774–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12979 (2020).

He, H., Reynolds, C. J., Li, L. Y. & Boland, J. Assessing net energy consumption of Australian economy from 2004-05 to 2014-15: environmentally-extended input-output analysis, structural decomposition analysis, and linkage analysis. Appl. Energy. 240, 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.02.081 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Air pollutant emissions from economic sectors in China: a linkage analysis. Ecol. Ind. 77, 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.02.016 (2017).

Gregori, T. & Pietroforte, R. An input-output analysis of the construction sector in emerging markets. Constr. Manage. Econ. 33, 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2015.1021704 (2015).

Sánchez-Chóliz, J. & Duarte, R. Production chains and linkage indicators. Econ. Syst. Res. 15, 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/0953531032000152335 (2003).

Chen, Z., Song, Y., Li,Y. & Li.Z. Assessing the contaminant reduction effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J. Clean. Prod. 424, 138887 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138887 (2023).

Li, Z., Li., Z.& Song, Y. Identification of key provinces and sectors for energy conservation in China: Linkage analyses based on the modified hypothetical extraction method. Energy Strategy Rev., 44, 100998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2022.100998 (2022).

Dietzenbacher, E., van Burken, B. & Kondo, Y. Hypothetical extractions from a global perspective. Econ. Syst. Res. 31, 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/09535314.2018.1564135 (2019).

Ali, Y., Sabir, M. & Muhammad, N. A comparative input-output analysis of the construction sector in three developing economies of South Asia. Constr. Manage. Econ. 37, 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1571214 (2019).

Li, Z. C., Lin, Y. Y., Song, Y. & Li, Z. Y. Linkages and flow paths of energy consumption: evidence from China’s sectors. Energy Rep. 9, 4594–4603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2023.03.099 (2023).

Sajid, M. J., Shahani, N. M. & Ali, M. Calculating inter-sectoral carbon flows of a mining sector via hypothetical extraction method. J. Min. Environ. 10, 853–. https://doi.org/10.22044/jme.2019.8263.1701 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Industrial CO2 emissions in China based on the hypothetical extraction method: linkage analysis. Energy Policy. 62, 1238–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.045 (2013).

Deng, G. Y., Ma, Y., Zhang, L. & Liu, G. C. China’s embodied energy trade: based on hypothetical extraction method and structural decomposition analysis. Energy Sources Part. B-Economics Plann. Policy. 13, 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567249.2019.1572836 (2018).

Ünal, E., Lin, B. Q. & Managi, S. CO2 emissions embodied in bilateral trade in China: an input-output analysis. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 103 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107218 (2023).

Zhang, L., Liu, B., Du, J., Liu, C. L. & Wang, S. CO2 emission linkage analysis in global construction sectors: alarming trends from 1995 to 2009 and possible repercussions. J. Clean. Prod. 221, 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.231 (2019).

Chen, J. D., Shi, Q. & Zhang, W. Structural path and sensitivity analysis of the CO2 emissions in the construction industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 92 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106679 (2022).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Structural path decomposition analysis of resource utilization in China, 1997–2017. J. Clean. Prod. 322 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129006 (2021).

Wu, J. X., Chen, M. X., Sun, X. L. & Meng, Z. The temporal variation of CH4 emissions embodied in Chinese supply chains, 2000–2020. Sci. Rep. 14, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62979-z (2024).

Mitoma, H., Nagashima, F., Kagawa, S. & Nansai, K. Critical supply chains for mitigating PM2.5 emission-related mortalities in India. Sci. Rep. 11, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91438-2 (2021).

Wang, Z., Cui, C. & Peng, S. Critical sectors and paths for climate change mitigation within supply chain networks. J. Environ. Manage. 226, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.08.018 (2018).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Identifying hotspots of sectors and supply chain paths for electricity conservation in China. J. Clean. Prod. 251 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119653 (2020).

Guerra, A. I. & Sancho, F. Measuring energy linkages with the hypothetical extraction method: an application to Spain. Energy Econ. 32, 831–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2009.10.017 (2010).

Duarte, R., Sánchez-Chóliz, J. & Bielsa, J. Water use in the Spanish economy: an input-output approach. Ecolog Econ. 43, 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0921-8009(02)00183-0 (2002).

Li, K. et al. Mapping spatial supply chain paths for embodied water flows driven by food demand in China. Sci. Total Environ. 786 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147480 (2021).

Wang, S. G. & Chen, B. Unraveling energy-water nexus paths in urban agglomeration: a case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Appl. Energy. 304 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117924 (2021).

Yang, L. G., Li, L. L., Zhu, K. F., Xie, R. & Wang, Z. G. Structural path analysis of China’s coal consumption using input-output frameworks. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 6796–6812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07176-6 (2020).

Li, J. L. & Yang, L. S. Back side of the coin: how does non-fossil energy diffusion result in less efficient fossil-based technologies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 96 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106848 (2022).

Yi, S., Abbasi, K. R., Hussain, K., Albaker, A. & Alvarado, R. Environmental concerns in the United States: can renewable energy, fossil fuel energy, and natural resources depletion help? Gondwana Res. 117, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2022.12.021 (2023).

Shi, L. G. et al. Comparative study of greenhouse gas emission calculations and the environmental impact in the life cycle assessment of buildings in China, Finland, and the United States. J. Building Eng. 70 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106396 (2023).

Adua, L. & Clark, B. Even for the environment, context matters! States, households, and residential energy consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab1abf (2019).

Wu, X. D., Guo, J. L., Ji, X. & Chen, G. Q. Energy use in world economy from household-consumption-based perspective. Energy Policy. 127, 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.005 (2019).

Nematchoua, M. K., Asadi, S. & Reiter, S. Estimation, analysis and comparison of carbon emissions and construction cost of the two tallest buildings located in United States and China. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 9313–9328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03799-w (2022).

Liang, S. B., Gu, H. M. & Bergman, R. Environmental life-cycle assessment and life-cycle cost analysis of a high-rise mass timber building: a case study in Pacific Northwestern United States. Sustainability. 13, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147831 (2021).

AIA. AIA Guide to Building Life Cycle Assessment in Practice. (2023).

Jiang, Z. J., Lyu, P. J., Ye, L. & Zhou, Y. W. Green innovation transformation, economic sustainability and energy consumption during China’s new normal stage. J. Clean. Prod. 273, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123044 (2020).

Nakaishi, T., Kagawa, S., Takayabu, H. & Lin, C. Determinants of technical inefficiency in China’s coal-fired power plants and policy recommendations for CO2 mitigation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 52064–52081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14394-4 (2021).

EIA. Analysis of Heat Rate Improvement Potential at Coal-Fired Power Plants (U.S. Energy information Administration, 2015).

EIA. Capital Cost and Performance Characteristic Estimates for Utility Scale Electric Power Generating Technologies (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2020).

Wang, R. C. et al. A novel system for reducing power plant electricity consumption and enhancing deep peak-load capability. Energy. 295, 17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.131031 (2024).

IEA. (ed IEA) (2023).

Berrill, P. & Hertwich, E. G. Material flows and GHG emissions from housing stock evolution in US counties, 2020-60. Build. Cities. 2, 599–617. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.126 (2021).

Funding

This research was supported by the Macau University of Science and Technology Foundation (FRG-24-033-TISD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. designed the research project, conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, and was involved in writing and revising the manuscript.Y.S. supervised the entire research project and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, Y., Song, Y. Comparative analysis of CO2 emission linkages of construction between China and the United States using structural path analysis. Sci Rep 14, 26493 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77679-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77679-x