Abstract

Geopolymer concrete (GPC) offers a sustainable alternative by eliminating the need for cement, thereby reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Using durable concrete helps prevent the corrosion of reinforcing bars and reduces spalling caused by chemical attacks. This study investigates the impact of adding 5, 10, and 15% silica fumes (SF) on the mechanical and durability properties of GPC cured at 60 °C for 24 h. In the research, concrete specimens were submerged continuously for 62 days in four different chemicals: 6% sodium sulfate, 6% sodium chloride, 2% sulfuric acid, and 2% hydrochloric acid. The study assessed the effects of chemical exposure on concrete properties by examining water absorption, sorptivity, and compressive strength loss in GPC specimens. Maximum compressive strength, split tensile strength, and flexural strength of about 48.35 MPa, 4.91 MPa, and 5.01 MPa are achieved after incorporation of 10% SF in GPC after 28 days of curing. Results indicated that GPC with a significant dosage of SF (10%) improves its mechanical and durability properties. The maximum rebound number and ultrasonic pulse velocity are achieved after 90 days of curing with a 10% dosage of SF. Moreover, an economic analysis was conducted to confirm the economic viability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete usage has witnessed a significant surge in recent years, leading to a corresponding increase in the demand for cement as a binding material. Globally, cement consumption has been on a steady rise, with over 2.8 billion tons of cement produced annually to meet the growing needs of the infrastructure sector, experiencing an annual growth rate of approximately 3%1,2,3. Notably, the production of each ton of cement results in the release of approximately one ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere annually. Given the extensive reliance on concrete, there is a compelling imperative to explore alternative binding materials4,5. One such alternative gaining prominence is geopolymer, a novel binder that offers a viable substitute for cement in the construction industry. Geopolymer is formed through the combination of alumino-silicate source materials with an alkaline solution, resulting in the formation of a precipitate that solidifies into geopolymer concrete (GPC), boasting lower carbon emissions compared to conventional cement-based concrete6,7. GPC also mitigates issues such as shrinkage-induced cracking commonly associated with excessive cement use. The formation of GPC entails the creation of a network comprising alumina and silicate, characterized by the formula Mn-[-(SiO2)z-AlO2]n.wH2O, where ‘n’ and ‘M’ denote the degree of polycondensation and monovalent cations (K+, Na+), respectively8.

A diverse range of materials, including fly ash, rice husk ash, red mud, silica fumes (SF), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), and natural zeolites like metakaolin, serve as viable sources for GPC production9,10. Incorporating GGBS and other industrial byproducts into alkali-activated concrete facilitates the development of a compact microstructure under ambient curing conditions11. This densification of the matrix significantly enhances the material’s mechanical properties, contributing to improved overall performance11. In addition to the aforementioned materials, natural zeolitic substances such as metakaolin are utilized as source materials due to their significant chemical composition and amorphous structure12. GGBS are particularly favored due to their abundant availability and high silica and alumina content, thereby addressing the challenge of industrial byproduct disposal. GPC exhibits favorable physical properties, including robust compressive strength and resilience to harsh conditions such as acid corrosion, high temperatures, and sulfate attack, rendering it a versatile and effective binder for construction and repair materials12,13,14. According to Paruthi et al.15, the compressive strength (CS) and durability are influenced by water to solid ratio (W: GPS). The CS of GPC is decreased with an increase in W: GPS ratio. The workability of GPC also becomes high when we increase the W: GPS. For the geopolymer mortar, Zhang et al.16 investigated the influence of W: GPS, and it was observed that the strength of geopolymer mortar started decreasing with increasing W: GPS ratio.

According to Swathi et al.17, the factor that influences the strength of GPC is the alkaline liquid to precursor ratio. It was noticed that the strength of GPC increases with an increase in the alkaline liquid to precursor ratio. However, with a higher alkaline liquid-to-preparator ratio, strength starts decreasing. According to Amran et al.18, significant strength of GPC is achieved when we take this alkaline liquid to precursor ratio of nearly 0.4. A similar result is observed in which the strength of GPC increases with an increase in alkaline liquid to precursor ratio up to 0.4. In addition, a further increase in alkaline liquid to precursor ratio up to 0.45 results in a decrease in the strength of GPC19. According to Jindal et al.20, the ratio of sodium silicate to sodium hydroxide (Na2SiO3: NaOH) is another factor that influences the strength of GPC. The compressive strength is significantly increased with increases in Na2SiO3: NaOH ratio. It means that if the mass of Na2SiO3 is more than the mass of NaOH, the strength of GPC increases. According to Rashad et al.21, the optimum value of Na2SiO3: NaOH ratio is 2.5 for achieving significant strength. According to Pratap et al.22, the concentration of the alkaline solution is the other parameter that influences the strength of GPC, and this concentration is determined in terms of the molarity of NaOH. The alkaline solution in liquid state is prepared after mixing the flakes of NaOH with water. NaOH flakes are dissolved in water to produce different concentrations, ranging from 8 to 16 Molarity.

SF, due to its submicron particle size, is widely utilized to enhance the density of concrete by filling micro voids between cement particles. Elyamany et al. investigated the resistance of GPC to sulfuric acid, revealing that slag-based GPC exhibited superior resistance to sulfuric acid attack23. Kurtoğlu et al. further demonstrated that GPC composed entirely of GGBS showed improved strength properties compared to fly-ash-based GPC24. Okoye et al. highlighted that incorporating SF into GPC resulted in significantly enhanced resistance to 2% H2SO4 and 5% NaCl solutions, surpassing that of conventional concrete25. Shahmansouri et al. found that including up to 30% SF in GGBS-based GPC improved compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths by 30%, 25%, and 20%, respectively26. Mustakim et al. also observed an increase in early strength development in GGBS-based GPC with 1.5% SF replacement27. However, further research is necessary to comprehensively understand the mechanical and durability characteristics of GGBS and silica fume-blended GPC across various proportions.

Geopolymer materials have historically been perceived as relatively fragile and prone to cracking. During the priming of Geopolymer Composite, micro-cracks of varying lengths initially emerge, which gradually coalesce into larger, macroscopic cracks. To address this issue, fibers are incorporated into geopolymer matrices to effectively manage these cracks by bridging the gaps and redistributing loads during processing. Recent advancements in research have significantly enhanced the engineering characteristics of geopolymer materials. While microfibers play a crucial role in delaying the formation of shaped cracks, they do not entirely prevent their initiation. The development of new microfibers has opened up a new avenue for strengthening GPC at the micro level. Ongoing research aims to explore the enhancement of microscale properties through the incorporation of micromaterial i.e. SF. The primary objective of the proposed study is to establish micro-engineered materials with improved properties and investigate the alterations in strength, mechanical performance, and durability of GPC-based reinforced with SF. The objective of this research is to study the effect of the incorporation of micromaterial on the mechanical strength of GPC. In addition, this study also analyses the effect of exposure of GPC to harmful acid and base chemicals on the strength properties of GPC. The non-destructive analysis has been done to obtain the empirical relationship for predicting the compressive strength of GPC. The durability of SF-incorporated GPC is determined with the help of sorptivity and water absorption parameters. Moreover, cost analysis and benefit/cost analysis were conducted for economic feasibility, resource allocation, cost efficiency, sustainability and environmental impact, competitive advantage, justification for investment, and improved decision-making.

Materials & methodology

Materials

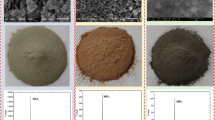

GGBS, a byproduct of the steel and iron industries produced in blast furnaces, was utilized in this study. The GGBS was procured from “Prime Cement Private Limited in Behror, India”, ensuring compliance with IS 12,089 standards (R2008)28. Laboratory analysis was conducted to determine its physical properties, the results of which are detailed in Table 1. Testing is done as per IS 8112 − 201329. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of precursor GGBS and additive SF has been done and the morphology of these materials is shown in Fig. 1a, b respectively. Morphology clearly shows that GGBS is irregular in shape and particles are closely packed whereas the SF particles are spherical in shape and closely packed to fill the voids of GPC and produce dense concrete.

In this study, SF was selected as a crucial supplementary material sourced from “Amorphous Chemicals Private Limited in New Delhi, India”. SF is a byproduct derived from the electric arc furnace production process of elemental silicon or silicon alloys. It complies rigorously with the IS 15,388 − 2003 (R2017)30 standards, ensuring quality and consistency in its chemical composition and physical attributes. Laboratory investigations, following the guidelines outlined in IS 8112 − 201329, comprehensively evaluated SF’s physical properties, which are detailed in Table 1.

NaOH is used in flakes form, which is white in color and kept in airtight container. NaOH is dissolved in water one day before the day of casting of the specimen. After all, mixing sodium hydroxide flakes in water results in the evaluation of heat during the preparation of an alkaline solution. NaOH is collected from “Babu Ram & Sons Private Limited, Tilak Nagar, New Delhi, India.” A significant solution explored in this study is sodium silicate, available in liquid form at various concentrations and also referred to as glassy water31. It is characterized as a yellow-colored jelly liquid with a specific gravity of 1.5. Sodium silicate comprises SiO2 (29.29 wt%), Na2O (13.99 wt%), and water (56.72 wt%), indicating its composition and aqueous nature essential for various applications.

For this research, locally sourced Badarpur sand from a quarry in Faridabad, Haryana, India, was utilized as the primary fine aggregate. The sand’s grading and fineness modulus, detailed in Table 2 following IS 2386 Part 1-201632, were carefully evaluated to ensure suitability for construction purposes. To prepare the sand for testing, any clay lumps and foreign materials were meticulously removed through a washing process followed by air-drying. Comprehensive sieve analysis results and the physical properties of the fine aggregate (FA) are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively, offering insights into its granular characteristics and quality parameters.

Coarse aggregate (CA) of 10 mm and 20 mm size used in the mix design was directly obtained from the crusher located in Faridabad, Haryana. The testing was done as per IS 2386 Part 1-201632. The CA was washed to remove dirt, dust, and then dried. Sieve analysis for aggregate was performed in the laboratory. The crushed stone aggregate of 10 mm and 20 mm size was mixed in proportion 60:40 proportions to meet IS 383–201633 requirement. The sieve analysis and physical properties of CA are listed in Tables 4 and 5.

In order to meet the specified workability standards outlined in IS 1199 (R2018)34, superplasticizer (SP) was incorporated into the mix design of GPC to regulate both workability and water content. The superplasticizer used throughout the experimental phase was based on sodium naphthalene formaldehyde. This SP, sourced from “Babu Ram & Sons Private Limited in Tilak Nagar, New Delhi, India”, was in powdered form and was selected for its ability to enhance the workability of GPC mixes effectively19,35. Detailed physical properties of the SP are presented in Table 6, providing insights into its characteristics such as density and chemical composition.

Methodology

Various tests were conducted as per the recommendations of the relevant Standard Code of Practices28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The G30 grade concrete with different SF dosages (5%, 10%, and 15% by wt. of GGBS) was studied and the results are compared with the standard G30 grade-controlled GPC. Moreover, the concentration of NaOH was fixed at 16 M as it was shown in literature as the optimum concentration36,37. The mix proportion of the G30 grade is shown in Table 7. The methodology of the preparation of GPC in the current study is shown in Fig. 2.

Testing procedures

Slump test

The first test on the freshly prepared GPC was slump test for measuring the workability of the freshly prepared GPC mix. The slump test as per IS 1199 (R2018)34 indicates a compacted concrete cone’s behavior under the action of gravitational forces. For the present study, the control GPC was designed to have a slump lying between 100 and 150 mm for desired G30 grade concrete. The mixing of different materials for the preparation of GPC mix is done in a pan mixer, as shown in Fig. 3a. The slump test performed is shown in Fig. 3b.

Compressive strength (CS) test

In this study, the performance and composition of GPC were evaluated through the casting of 150 × 150 × 150 mm specimens in the laboratory, as depicted in Fig. 3c. To assess its strength characteristics, CS tests were conducted in accordance with IS 516 (R2021)38. A total of 48 GPC cube samples were fabricated, each designated for specific testing purposes. The constituent materials included GGBS, SF, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, superplasticizer, NaOH, Na2SiO3, and water, each chosen for their discussed properties and roles in the concrete mix. The GPC grade selected for this study was G30. Following casting, molds were removed after 24 h and specimens were subjected to oven curing at 60 °C for one day, as illustrated in Fig. 3d. Subsequently, the specimens underwent water curing for 7, 28, 56, and 90 days to facilitate optimal strength development. Prior to testing in the Compressive Testing Machine (CTM), the surfaces of the GPC cubes were carefully dried with cloth, ensuring accurate and consistent test conditions, as shown in Fig. 4a.

Split tensile strength (STS) test

STS test of the concrete was done to assess the tensile strength of GPC. The STS test was performed as per IS 5816-(R2004)39. A total of 36 cylindrical specimens of size 100 mm diameter and 200 mm long were cast and demolded after 24 h and kept in an oven for 1 day at a temperature of 60 °C. Further, after 28, 56, and 90 days, the casted cylinders were taken out from the curing tank, and the surfaces of the cylinders were dried with the piece of cloth, and then it was kept under CTM to ascertain the tensile strength of GPC as shown in Fig. 4b.

Flexural strength (FS) test

FS was performed on beams of size 100 mm breadth, 100 mm height, and 500 mm length. The test was conducted as per the IS 516–202138 (reaffirmed in 2004). Total 24 beams were cast and demolded after 24 h and kept in an oven for 1 day at temperatures of 60 °C. Further, after 28, and 90 days, the casted beams were taken out from the curing tank and the surfaces of the beams were dried with the piece of cloth for testing. For testing the rectangular prism beams, two-point loads were applied on the rectangular prism beam’s top surface, as shown in Fig. 4c.

Water absorption test

In assessing the durability of GPC, water absorption plays a critical role. As part of this study, a water absorption test was conducted on 150 mm cubic specimens following ASTM C64240 standards. Initially, the GPC specimens underwent oven drying at 60 °C for one day, followed by natural conditioning at room temperature for an additional day to stabilize. The initial weight (W1) of each specimen was then measured. Subsequently, the GPC cubes were submerged in water and their weights were recorded after cleaning with cloth at 1-hour, 12-hour, 24-hour, and 72-hour intervals to determine the final weight (W2). The water absorption capacity was calculated using Eq. (1), providing crucial insights into the material’s ability to withstand moisture ingress over time. This test methodology ensures a comprehensive evaluation of GPC’s performance in varying environmental conditions, contributing valuable data to its durability assessment.

Sorptivity test

Sorptivity serves as a critical indicator of its water permeability and capillary action characteristics. This study assesses sorptivity before and after exposure to chemicals, following ASTM C64240 guidelines. Initially, GPC cubes were prepared and subjected to oven drying at 60 °C for one day, followed by a cooling period at room temperature for an additional day. To initiate the sorptivity test, all external cube surfaces, except the base, were meticulously taped to prevent water ingress from the sides and top, ensuring controlled water penetration through the base only, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. Subsequently, the cubes were immersed in a container with water, maintaining a water level 3–5 mm below the base. After 7 days, the cubes were removed, and the weight of each specimen was recorded after wiping the exposed bottom surface with a cloth to eliminate any residual chemicals. Sorptivity values were then calculated using Eqs. (2–3), providing insights into the GPC’s ability to resist liquid penetration under chemical exposure conditions. This methodology offers valuable data on the material’s durability performance and its potential applications in various environmental settings.

Where The constant ‘I’ is derived from Eq. (3), representing a material-specific coefficient. The variable ‘t’ denotes the duration of the specimen’s exposure to the liquid, while ‘δm’ signifies the change in the specimen’s mass in grams due to liquid absorption. Additionally, ‘a’ refers to the surface area of the cube (mm²), and ‘d’ represents the water density (g/mm³). These parameters collectively facilitate a comprehensive analysis of the GPC’s ability to absorb and transmit water under capillary action, essential for evaluating its long-term durability and performance in various environmental conditions.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 6% sodium chloride (NaCl) solution

The durability of GPC is the most important aspect of the concrete defining the longevity to sustain loads. A good quality concrete is the one with a better durability aspect. The durability qualities of GPC are its ability to resist the chemical attack caused due to NaCl present in water. The present study deals with examining the SF effect and its composites in an aggressive environment. The GPC cubes were cast in the laboratories. A total of 12 GPC cubes with G30 grade (with and without SF) were cast, and specific nomenclatures were allotted to them. After casting, the cubes were removed from the molds after 24 h and the specimens were kept in an oven for 1 day after removal of molds at a temperature of 60 °C and then cured in normal water for 28 days in a curing tank reservoir. The cubes were then kept for 62 days in kept in 6% NaCl in water by weight. After curing, the cubes were tested under CTM up to the collapse. The NaCl used for the preparation of harmful exposed conditions is shown in Fig. 5b. The preparation of harmful chemical curing conditions for GPC cubes is shown in Fig. 5c.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 6% sodium sulphate (Na2SO4) solution

The durability qualities of GPC are its ability to resist the chemical attack caused due to Na2SO4 present in water. The present study deals with the SF effect and its composites in an aggressive environment. The GPC cubes were cast in the laboratories. A total of 12 GPC cubes with G30 grade (with and without SF) were cast, and specific nomenclatures were allotted to them. After casting, the cubes were removed from the molds after 24 h and the specimens were kept in an oven for 1 day after removal of molds at a temperature of 60 °C and then cured in normal water for 28 days in a curing tank reservoir, the cubes were then kept for 62 days in kept in 6% Na2SO4 in water by weight. After curing, the cubes were tested under a CTM up to the collapse.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 2% hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution

Another durability aspect to be studied for the GPC is to assess the concrete under the influence of acid attack, i.e., hydrochloric acid (HCl). Hence, in order to analyze the impact of micro additives and their composites in the acidic environment, the GPC cubes were cast in the laboratory. A total of 12 GPC cubes with G30 grade (with and without SF) were cast, and specific nomenclatures were allotted to them After casting, the cubes were removed from the molds after 24 h and the specimens were kept in an oven for 1 day after removal of molds at temperature of 60 °C and then cured in normal water for 28 days in curing tank reservoir, the cubes were then kept for 62 days in 2% HCl solution in water by weight. After a total of three months from the day of casting, the cubes were taken out from the HCl-water solution, and the cube’s surface was dried and then analyzed in the CTM to ascertain the CS of the GPC.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 2% sulphuric acid (H2SO4) solution

To assess the concrete’s impact of another acid attack, i.e., H2SO4, the GPC cubes were cast in the laboratory. A total of 12 GPC cubes with G40 grade (with and without SF) were cast, and specific nomenclatures were allotted to them After casting, the cubes were removed from the molds after 24 h and the specimens were kept in an oven for 1 day after removal of molds at different temperature of 60 °C and then cured in normal water for 28 days in curing tank reservoir, the cubes were then kept for 62 days in 2% H2SO4 solution in water by weight. After a total of three months from the day of casting, the cubes were taken out from the H2SO4-water solution, and the cube’s surface was dried and then analyzed in the CTM to ascertain the CS of the GPC.

Non-destructive test: rebound hammer (RH) test

RH test was conducted on the 150 mm x 150 mm x 150 mm cube after cleaning, and drying the smooth surface. All the surfaces should be smoothened with the help of rubbing with stone. The hammer should be impacted 20 mm away from the edge of the cube. The RH should be kept perpendicular to the surface of a specimen. A number of observations on each surface of the cube were taken and the mean of all readings gives the strength of GPC. The RH test was conducted after 7, 28, 56, and 90 days of curing to know the effect of the incorporation of SF in GPC in terms of penetration resistance. The RH test was performed as per IS 13,311(2)-1992 guidelines41.

Non-destructive test: ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) test

UPV test was conducted on GPC 150 mm x 150 mm x 150 mm specimen. In the UPV test velocity of the ultrasonic pulse was determined after 7, 28, 56, and 90 days by direct, semi-direct, and indirect transmission. The UPV test was performed as per IS 13,311(2)-1992 guidelines41.

Results & discussion

Workability

Figure 6 presents the slump values measuring the workability of the GPC mix. It can be seen that compared with a normal GPC mix, the reduction in the slump values is in SF-based GPC. The reduction in the slump value was caused by the larger surface area of micro particles, which required excess water for the mix. This excess water demand was controlled by the additional dosage of superplasticizer in the GPC mix. The mix containing SF reported a decrease in slump as the dosage of SF was increased.

It has been reported that the incorporation of nanoparticles in alkali-activated slag concrete leads to a reduction in slump values. This effect is attributed to the smaller particle size of the nanoparticles compared to slag grains, as well as their larger aspect ratios, which result in higher water absorption42.

Compressive strength (CS)

As shown in Fig. 7 among the three dosages of SF incorporated GPC mixes, the highest increment in the CS at 28 days compared to normal GPC mix was noted as 5.79% at 10% dosage of SF cured at 60 °C for 1 day. The respective increments for SF were observed as 0.13% at 5% SF and 0.63% at 15% SF in comparison with normal GPC mix cured for 28 days respectively. The same pattern of increment was observed at 7, 56, and 90 days, respectively. The comparison of the increase in CS at different dosages of SF is shown in Fig. 8. The reason for the gain in strength at 7, 28, 56, and 90 days may be attributed to the incorporation of microparticles in the mix, which made the matrix stronger. A very strong bond seems to exist between the matrix ingredients, which further makes it impermeable.

The maximum strength at 90 days for GPC cured at 60 °C for 1 day was 53.99 MPa, 55.71 MPa, and 54.02 MPa for 5%, 10%, and 15% SF respectively. Hence from the above discussion, it is concluded that by the inclusion of microparticles, the normal G30 grade GPC attains much higher strength thus getting transformed to higher strength GPC. The increase in CS is likely due to the formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel within the matrix, which enhances binding and densifies the material, leading to improved CS43,44,45.

Split tensile strength (STS)

From Fig. 8, it was noticed that STS increases as the dosage of the microparticle is increased. The maximum increase was observed in NS-based GPC. An increase of about 8.3% at 28 days with normal mix was observed in SF based GPC at 60 °C 1 day curing with 10% dosage as compared to 2.64% and 2.2% in 5% and 15% SF incorporated GPC respectively. Figure 9 shows the comparative increment in the tensile strength graphically.

The reason for the gain in the tensile strength was due to the presence of micro particles which improve the fracture properties of the geopolymer matrix, by controlling the matrix cracks at micro scale46,47,48. The notable enhancement in STS can be attributed to the improvement of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between silica-reinforced aggregates and the surrounding cementitious matrix. The fine particle size of silica allows it to penetrate the micropores within the ITZ, acting as both a filler and compaction agent. This process strengthens the ITZ, effectively reducing its inherent weaknesses and enhancing the bond strength at the interface between the aggregate and the binder. This optimized bond contributes significantly to the overall improvement in STS47.

Flexural strength (FS)

From Table 8, it is concluded that FS increases with an increment in the dosage of microparticles. A remarkable increase of about 3.94% at 28 days after being cured at 60 °C in an oven for 1 day with normal mix was observed in SF-based GPC beams at 10% dosage as compared to 2.07% and 0.41% in 5% SF dosage and 15% SF based GPC respectively. Also, from Table 8, it was observed that the FS calculated experimentally was more than the FS calculated as per IS 456–200049.

Figure 9 provides a comparison of FS. The gain in FS is due to the presence of microparticles which improves the GPC’s compaction and densification properties which further improve the fracture properties of the geopolymer matrix, by controlling the matrix cracking at micro-scale level.

The rapid early strength gain can be attributed to several factors, including enhanced pozzolanic reactivity due to elevated calcium content and an increased surface area of the reactants. These factors promoted greater calcium activity, leading to the accelerated formation of C-S-H and aluminosilicate phases, which contributed to the material’s improved FS11.

Durability test: water absorption test

From Fig. 10 it is observed that the water absorption effect on GPC decreases with an increase in the dosage of micromaterial for all GPC cubes. The SF-based GPC imparts 12.72% decrement in water absorption of GPC with 15% SF dosage in comparison with controlled GPC.

The reduction in water absorption is due to the filling of voids and cracks at the macro, and micro levels. Water absorption is also reduced with an increase in 1 day curing in an oven before curing in tap water at room temperature. Water absorption of GPC with and without incorporation of SF is shown in Fig. 10. This observation may be attributed to the formation of denser specimens, as the mix incorporates a higher calcium content from GGBS, rendering the samples less susceptible to cracks and voids. Similar findings have been reported by other researchers, who noted that the reduced water absorption was a result of the presence of finer, more tortuous, and closed pore structures in alkali-activated slag specimens, which significantly hinder the penetration of water42,50.

Durability test: sorptivity test

From Fig. 11 it is observed that the sorptivity effect on GPC decreases with an increase in the dosage of micromaterial for all GPC cubes. The SF-based GPC with 15% SF imparts a maximum decrement of 15.92% at 30 min in comparison with controlled GPC. In the initial stages, the disparity in sorptivity among all GPC specimens cured at 60 °C temperature is minimal, primarily attributable to capillary forces driving absorption.

However, significant variations in sorptivity emerge at later stages, predominantly stemming from the pore-filling effects of SF across all percentages of dosage. Figure 12 portrays the comparison of the sorptivity results of SF-based GPC cured at 60 °C. The alkali concentration and silicate ratio play a crucial role in influencing sorptivity values. Based on the CS and sorptivity test outcomes, it is evident that as the CS increases, the corresponding sorptivity value decreases, and conversely, lower CS is associated with higher sorptivity values42,50.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 6% sodium chloride solution

From Fig. 12 it can be seen that the effect of sodium chloride on GPC is less significant when the dosage of micromaterial is increased. The SF-based GPC with 10% SF imparts a maximum CS of 48.12 MPa at 90 days as against 47.12 MPa of controlled GPC mix, 48.11 MPa of SF with 5% dosage, and 47.69 MPa with 15% SF-based GPC mixes, respectively for 60 °C cured GPC. The reduced effect of chloride attack on micromaterial-based GPC and increase in CS was due to the filling of voids by the larger surface area of the microparticles which makes the GPC impermeable and also makes it a denser and compact GPC.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 6% sodium sulphate solution

From Fig. 13 it can be seen that the effect of sodium sulphate on GPC is less significant when the dosage of micromaterial is increased. The SF-based GPC with 10% SF imparts a maximum CS of 46.74 MPa at 90 days as against 43.25 MPa of controlled GPC mix, 46.11 MPa of SF with 5% dosage and 44.14 MPa with 15% SF based GPC mixes, respectively for 60 °C cured GPC. The diminution of the effect of Na2SO4 attack on micromaterial-based GPC and the increase in the CS was due to the filling of pores and voids by the larger surface area of the microparticles within the GPC. Moreover, the outer surface of the GPC cube, which was in contact with Na2SO4, has deteriorated. However, the Na2SO4 effect did not propagate due to the lesser pores inside the GPC, hence resulting in better CS of micromaterial-based GPC.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 2% hydrochloric acid solution

From Fig. 14, it was concluded that the effect of HCl on GPC decreases with an increase in the dosage of micromaterials.

The SF-based GPC with 10% SF imparts a maximum CS of 42.04 MPa at 90 days as against 36.25 MPa of controlled GPC mix, 41.87 MPa of SF with 5% dosage, and 41.05 MPa with 15% SF based GPC mixes, respectively for 60 °C cured GPC. The diminution of the effect of HCl attack on micromaterial-based GPC and the increase in the CS was due to the filling of pores and voids by the larger surface area of the nanoparticles within the GPC. However, the HCl effect did not propagate due to the fewer pores inside the GPC, hence resulting in better CS of micromaterial-based GPC.

Durability test: concrete exposure to 2% sulphuric acid solution

From Fig. 15, it is observed that the effect of H2SO4 on GPC decreases with an increase in the dosage of micromaterial. The SF-based GPC with 10% SF imparts a maximum CS of 40.99 MPa at 90 days as against 34.91 MPa of controlled GPC mix, 40.78 MPa of SF with 5% dosage, and 35.39 MPa with 15% SF-based GPC mixes, respectively for 60 °C cured GPC.

The decreasing effect of sulphuric acid attack on micromaterial-based GPC and the increase in the CS was due to the pore refining of the internal structure of GPC by microparticles present. The effect of H2SO4 did not propagate further inside due to the lesser pores in the GPC, resulting in the better CS of micromaterial-based GPC.

Non-destructive test: RH test

To check the penetration resistance and quality of GPC, RH test was performed on the GPC cubes before the compressive strength test. Figure 16 shows the results of Non-Destructive tests on the GPC incorporated with SF. It was noticed that RN is increases with an increase in the percentage of incorporation of SF for all the curing periods up to 10% SF. But with a further increase in the dosage percentage of SF, the RN starts decreasing.

The maximum value of RN is 56.81, which is achieved at 10% SF dosage after 90 days of curing. The increase in rebound number can be attributed to the dense and compact microstructure of the material. This compact matrix is formed due to the packing effect of SF in the voids of the GPC matrix. The refinement of voids and the densified microstructure are likely the primary reasons behind the enhanced rebound number, as noted by Muduli51.

The calibration curve of RN vs. CS is shown in Fig. 17. The best-fitted line for the calibration is a straight line. The relationship between CS and RN is given by Eq. (4).

Where CS is the compressive strength and RN is the rebound number. A total of 20 mean observations were used in the development of the relationship between CS and RN. The coefficient of correlation R2 value is found to be 0.9554.

Non-destructive test: UPV test

Figure 18 shows the UPV test results for the GPC incorporated with different percentages of dosage of SF. It was noticed that UPV increases with an increase in the percentage of SF dosage up to 10% for the curing period. UPV lies between 3.25 and 3.65 km/s for 7 days curing, 3.41–4.08 km/s for 28 days curing, 4.11–4.19 km/s for 56 days curing, 4.15–4.88 km/s for 90 days curing. This reaction led to the expansion and the development of additional cracks within the concrete, consequently causing a reduction in UPV values42,52. The UPV of the GPC mixes ranges from 3.5 to 4.5 km/s which means Good category while higher than 4.5 km/s UPV value means Excellent category as per to IS 13,311-part 141.

A straight line is best fitted for representing the relationship between UPV and CS test results shown in Fig. 19. The developed relationship with CS and UPV is given by Eq. (5).

A total 20 mean observations were used in the development of a relationship between CS and RN. The coefficient of correlation R2 value is found to be 0.9637.

Economic analysis

Cost analysis

The cost analysis conducted in this study explores the financial implications of completely replacing cement with GGBS and SF in the production of sustainable concrete. This analysis provides a comparative assessment of costs between GGBS-based reinforced with SF and conventional GPC, highlighting the economic viability of incorporating 100% GGBS and three different percentages of SF (5, 10, 15%) into GPC manufacturing processes. To evaluate the economic feasibility of GPC-based micro-composites reinforced with SF, a comprehensive examination of associated expenses was undertaken. While the initial costs of GGBS-based micro-composites reinforced with SF GPC, especially those utilizing 100% GGBS and SF, may appear lower compared to conventional GPC, it is essential to consider the long-term benefits of such materials. These benefits include enhanced mechanical properties and reduced ecological impacts, which can lead to lower maintenance and repair costs over time. The insights from this cost analysis significantly contribute to understanding the economic implications of integrating GGBS and SF into concrete production. This information is valuable for both academic researchers and industry professionals, as it enhances their understanding of the financial viability and potential benefits of these materials for construction applications.

Several factors were considered when comparing GGBS-based micro-composites reinforced with SF GPC to conventional GPC from an economic perspective, including CS, STS, and FS. The study identified the optimal concentration of NaOH at 16 M and determined material costs based on current pricing in the Indian market, converted to US dollars at an exchange rate of 1 US dollar ($) to 84 Indian rupees (₹)19. The findings underscore the potential long-term economic benefits of adopting GGBS-based reinforced with SF GPC, emphasizing their contribution to sustainable and cost-effective construction practices. The current pricing of the materials used in this study are mentioned in Table 9.

The study conducted a detailed cost analysis for producing 1 m³ of 100% GGBS and SF-incorporated GPC with a strength of 30 MPa (G30). The primary ingredient for GPC is industrial waste by-products, making its material cost negligible, aside from transportation expenses. The significant cost components for GPC are sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate, used as alkaline activators. Thus, sourcing these materials from waste streams is crucial for minimizing production costs. As shown in Table 9, the production cost of GPC is lower than that of OPC, regardless of whether IS or ACI codes are used for design. The highest production cost is associated with OPC designed using ACI codes, while the lowest cost is associated with OPC designed using IS codes. This observation aligns with other researchers’ findings that GPC is generally less expensive than OPC due to the use of waste materials. However, some studies noted that GPC costs might be 1–2% higher than OPC in certain scenarios. Researchers in previous works examined the ecological footprint and cost of GPC compared to OPC for M40 and M30 grades concrete. Their findings indicate that the concrete designed using ACI codes is the most expensive19, and GPC is less costly than OPC designed using IS codes. These insights underscore the economic and environmental advantages of adopting GPC over traditional OPC in concrete production.

Benefit/cost analysis

The benefit/cost analysis conducted in this study evaluates the economic and performance advantages of GGBS-based GPC incorporating SF in comparison to conventional concrete. The analysis is based on the relative property enhancements and associated costs, where property improvement is quantified as a function of mechanical performance (e.g., compressive strength, tensile strength) and durability indicators (e.g., sorptivity, water absorption). In this study, the cost of materials (GGBS and SF) is kept constant across all mixes, allowing the focus to be on the economic efficiency derived from property improvements. The analysis is conducted using the following framework, as illustrated in Eqs. (6–8)53,54:

-

I: The absolute value of a specific property.

-

II: A relative improvement metric, calculated as the ratio of the property value of the mixture to that of the control concrete, modified by ± 1 to account for whether the property improvement is beneficial (e.g., higher strength) or detrimental (e.g., higher water absorption).

-

III: The benefit, calculated as the product of the improvement factor (II) and a weight factor (WF), which is assigned based on the importance of each property to the overall performance of the concrete mix.

The cost-benefit ratio is then determined by comparing the property improvements (benefits) to the cost of producing the specific concrete mixture, considering the fixed material costs and varying performance outcomes. This approach provides a holistic understanding of the value derived from each mix, balancing performance enhancements with material costs (Table 10).

The analysis of the results revealed that mixtures incorporating 10% SF demonstrated the highest benefit-cost ratios, reaching 0.038, indicating superior economic efficiency (refer to Table 10). Since the cost of the GGBS and SF components remained constant across all mixes, the benefit-cost ratio was predominantly influenced by the cost factor of the GGBS-based micro-composites reinforced with SF GPC. Conversely, mixtures with 15% SF showed the lowest benefits, with benefit-cost ratios of 0.007, despite their lower cost. Although the 10% SF mix had the highest cost compared to other percentages, the economic analysis indicated that GGBS-based micro-composites reinforced with SF GPC, particularly with a 16 M molarity inclusion rate, could be effectively utilized to maximize economic benefits.

Conclusion

Based on exhaustive experimental investigations to study the effect of incorporating SF on the strength of GGBS-based GPC, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

The workability of GPC decreases with the increase in the percentage of SF. However, the addition of SF enhances the mechanical strength of GPC by producing high-strength microcomposites and improves its fracture properties by controlling matrix cracks at the micro scale.

-

Incorporation of SF in GPC results in an increase in compressive strength. Specifically, GPC mixes cured at 60 °C for 1-day show increases of up to 0.13%, 5.79%, and 0.63% with 5%, 10%, and 15% SF, respectively, compared to the control mix at 28 days.

-

The STS increases up to 2.64%, 8.3%, and 2.2%, and FS increases up to 2.07%, 3.94%, and 0.41% for GPC mixes with 5%, 10%, and 15% SF, respectively, cured under the same conditions.

-

The durability of GPC against chemical attacks improves with the increase in SF. At 90 days, GPC with 10% SF shows significant increases in compressive strength when treated with solutions of 6% NaCl, 6% Na2SO4, 2% HCl, and 2% H2SO4, compared to normal GPC.

-

The addition of SF reduces water absorption, making GPC less porous. The sorptivity of GPC decreases with the increase in SF dosage, especially at an early age, due to the influence of capillary forces.

-

The optimum SF dosage for enhancing GPC strength properties is 10%. The RH and UPV tests both show improvements with increasing SF dosage up to 10%, indicating better compactness and strength.

-

The study confirms that the production cost of GPC (G30) is lower than that of OPC concrete of M30 grade, regardless of the design code used (IS or ACI). This cost advantage primarily arises from the utilization of industrial waste by-products as the main ingredients in GPC, reducing material costs significantly.

-

The cost analysis in this study shows that GPC offers both economic and environmental benefits by utilizing industrial by-products like GGBS and SF. While OPC designed with ACI codes is the most expensive, GPC remains consistently more economical than OPC designed with either IS or ACI codes, highlighting its potential as a sustainable and cost-effective alternative for concrete production.

-

The benefit/cost analysis indicates that incorporating 10% SF into GGBS-based composites provides the highest benefit-cost ratio of 0.038, demonstrating superior economic efficiency. Despite higher costs, the 10% SF mix optimally balances cost and performance, making it a valuable option for maximizing returns in GGBS-SF geopolymer concrete production.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request by Mr. Sagar Paruthi, Email id: sparuthi57@gmail.com.

Change history

01 July 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements section in the original version of this Article was incorrect. It now reads: “The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through project number: GSSRD-24."

References

Kaptan, K., Cunha, S., Aguiar, J. A Review : construction and demolition waste as a novel source for CO2 reduction in portland cement production for concrete. Sustainability 16, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020585 (2024).

Tekin, I. et al. Recycling zeolitic tuff and marble waste in the production of eco-friendly geopolymer concretes. J. Clean. Prod. 268, 122298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122298 (2020).

Yost, J. R., Radlińska, A., Ernst, S. & Salera, M. Structural behavior of alkali activated fly ash concrete. Part 1: mixture design, material properties and sample fabrication. Mater. Struct. 46, 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-012-9919-x (2013).

Scrivener, K. L. & Kirkpatrick, R. J. Innovation in use and research on cementitious material. Cem. Concr Res. 38, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2007.09.025 (2008).

Tanu, H. M. & Unnikrishnan, S. Review on durability of geopolymer concrete developed with industrial and agricultural byproducts. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.335 (2023).

Ma, C. K., Awang, A. Z. & Omar, W. Structural and material performance of geopolymer concrete: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 186, 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.111 (2018).

Çelikten, S., Sarıdemir, M., Özgür, İ. & Deneme Mechanical and microstructural properties of alkali-activated slag and slag + fly ash mortars exposed to high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 217, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.055 (2019).

Duxson, P. et al. Geopolymer technology: the current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 2917–2933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0637-z (2007).

Lloyd, N. A. & Rangan, B. V. Geopolymer concrete: a review of development and opportunities, in: In 35th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures, Singapore, : pp. 25–27. (2010).

Unnikrishnan, T. H. M. S. Utilization of industrial and agricultural waste materials for the development of geopolymer concrete- a review. Mater. Today Proc. 65, 1290–1297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.192 (2022).

Soumya Pradhan, S., Mishra, U. & Kumar Biswal, S. Parveen, Mechanical and microstructural study of slag based alkali activated concrete incorporating RHA. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132685 (2023).

Alahmari, T. S., Abdalla, T. A. & Rihan, M. A. M. Review of pecent developments regarding the durability performance of eco-friendly geopolymer concrete. Buildings 13, 3033. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13123033 (2023).

Iyer, N. R. An overview of cementitious construction materials, in: New Materials in Civil Engineering, Elsevier, : 1–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818961-0.00001-6. (2020).

Murmu, A. L., Dhole, N. & Patel, A. Stabilisation of black cotton soil for subgrade application using fly ash geopolymer. Road. Mater. Pavement Des. 21, 867–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680629.2018.1530131 (2020).

Paruthi, S. et al. A review on material mix proportion and strength influence parameters of geopolymer concrete: application of ANN model for GPC strength prediction. Constr. Build. Mater. 356, 129253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129253 (2022).

Zhang, P., Zheng, Y., Wang, K. & Zhang, J. A review on properties of fresh and hardened geopolymer mortar. Compos. B Eng. 152, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.06.031 (2018).

Swathi, B. & Vidjeapriya, R. Influence of precursor materials and molar ratios on normal, high, and ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete – a state of art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 132006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132006 (2023).

Amran, Y. H. M., Alyousef, R., Alabduljabbar, H. & El-Zeadani, M. Clean production and properties of geopolymer concrete; a review. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119679 (2020).

Paruthi, S., Rahman, I., Husain, A., Hasan, M. A. & Khan, A. H. Effects of chemicals exposure on the durability of geopolymer concrete incorporated with silica fumes and nano-sized silica at varying curing temperatures. Materials. 16, 6332. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16186332 (2023).

Jindal, B. B., Alomayri, T., Hasan, A. & Kaze, C. R. Geopolymer concrete with metakaolin for sustainability: a comprehensive review on raw material’s properties, synthesis, performance, and potential application. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 25299–25324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17849-w (2022).

Rashad, A. M., Mohamed, R. A. E., Zeedan, S. R. & El-Gamal, A. A. Basalt powder as a promising candidate material for improving the properties of fly ash geopolymer cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 435, 136805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136805 (2024).

Pratap, B., Mondal, S. & Hanumantha Rao, B. NaOH molarity influence on mechanical and durability properties of geopolymer concrete made with fly ash and phosphogypsum. Structures 56, 105035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105035 (2023).

Elyamany, H. E., Elmoaty, A. E. M. A. & Diab, A. R. A. Sulphuric acid resistance of slag geopolymer concrete modified with fly ash and silica fume. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. 45, 2297–2315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-020-00515-5 (2021).

Kurtoğlu, A. E. et al. Mechanical and durability properties of fly ash and slag based geopolymer concrete. 6, Adv. Concr Constr. 6 345–362. https://doi.org/10.12989/acc.2018.6.4.345 (2018). Accessed September 26, 2024.

Okoye, F. N., Prakash, S. & Singh, N. B. Durability of fly ash based geopolymer concrete in the presence of silica fume. J. Clean. Prod. 149, 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.176 (2017).

Shahmansouri, A. A., Nematzadeh, M. & Behnood, A. Mechanical properties of GGBFS-based geopolymer concrete incorporating natural zeolite and silica fume with an optimum design using response surface method. J. Building Eng. 36, 102138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102138 (2021).

Mustakim, S. M. et al. Improvement in fresh, mechanical and microstructural properties of fly ash- blast furnace slag based geopolymer concrete by addition of nano and micro silica. Silicon 13, 2415–2428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00593-0 (2021).

IS. 12089, Specification for granulated slag for the manufacture of Portland slag cement., New Delhi, (2008).

IS. 8112, Specification for 43 grade ordinary Portland cement by Bureau of Indian Standards (Bureau of Indian Standards, 2013).

IS. 15388, Specifications for silica fume, New Delhi (Reaffirmed 2017). (2003).

Anuradha, R., Sreevidya, V., Venkatasubramani, R. & Rangan, B. V. Modified guidelines for geopolymer concrete mix design using Indian standard (ASIAN JOURNAL OF CIVIL ENGINEERING (BUILDING AND HOUSING, 2012).

IS. 12269, Ordinary Portland cement, 53 grade – specification, New Delhi, (2016).

IS. 383:2016, Coarse and Fine Aggregate for Concrete Specification, New Delhi, (2016).

IS. 1199, Fresh concrete—methods of sampling, testing and analysis, New Delhi, (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Preparation, characterization and performances of powdered polycarboxylate superplasticizer with bulk polymerization. Materials 7, 6169–6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7096169 (2014).

Saini, G. & Vattipalli, U. Assessing properties of alkali activated GGBS based self-compacting geopolymer concrete using nano-silica. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 12, e00352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2020.e00352 (2020).

Parveen, Singhal, D., Junaid, M. T., Jindal, B. B. & Mehta A. Mechanical and microstructural properties of fly ash based geopolymer concrete incorporating alccofine at ambient curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 180, 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.286 (2018).

IS. 516, Indian Standard Methods of Tests for Strength of Concrete, New Delhi, (2021).

IS. 5816, Method of Test for Splitting Tensile Strength of Concrete, New Delhi, (2004).

ASTM C 642. Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concretes, West Conshohocken, PA, (2013).

IS. 13311(2), Non-Destructive Testing of Concrete - Method of Test - Part II Rebound hammer., New Delhi, (1992).

Shahrajabian, F. & Behfarnia, K. The effects of nano particles on freeze and thaw resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 176, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.033 (2018).

Saloni, P., Pham, T. M., Lim, Y. Y., Pradhan S. S., & Kumar J. Performance of rice husk ash-based sustainable geopolymer concrete with ultra-fine slag and corn cob ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 279, 122526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122526 (2021).

Saloni, A., Singh, V., Sandhu, Jatin & Parveen Effects of alccofine and curing conditions on properties of low calcium fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 32, 620–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.763 (2020).

Arora, S., Jangra, P., Pham, T. M. & Lim, Y. Y. Enhancing the durability properties of sustainable geopolymer concrete using recycled coarse aggregate and ultrafine slag at ambient curing. Sustainability 14, 10948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710948 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Effect of fine aggregate particle characteristics on mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Minerals 11, 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/min11080897 (2021).

Li, Z., Fei, M. E., Huyan, C. & Shi, X. Nano-engineered, fly ash-based geopolymer composites: an overview. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168, 105334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105334 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer concrete based on fly ash and coal gangue under different dosage and particle size of nano silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 387, 131622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131622 (2023).

IS. 456, Plain and Reinforced Concrete - Code of Practice, New Delhi, (2000).

Pradhan, S. S. et al. Effects of rice husk ash on strength and durability performance of slag-based alkali‐activated concrete. Struct. Concrete. 25, 2839–2854. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202300173 (2024).

Muduli, R. & Mukharjee, B. B. Effect of incorporation of metakaolin and recycled coarse aggregate on properties of concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 209, 398–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.221 (2019).

Huseien, G. F. & Shah, K. W. Durability and life cycle evaluation of self-compacting concrete containing fly ash as GBFS replacement with alkali activation. Constr. Build. Mater. 235, 117458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117458 (2020).

Alyaseen, A. et al. Influence of silica fume and Bacillus subtilis combination on concrete made with recycled concrete aggregate: experimental investigation, economic analysis, and machine learning modeling. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02638 (2023).

Siddique, R. et al. Effect of bacteria on strength, permeation characteristics and micro-structure of silica fume concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 142, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.057 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through project number: GSSRD-24.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sagar Paruthi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing–review & editing.Ibadur Rahman, Afzal Husain Khan: Supervision, Validation, VisualizationNeha Sharma: Supervision, Validation, VisualizationAfzal Husain Khan, Ahmad Alyaseen: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paruthi, S., Rahman, I., Khan, A.H. et al. Strength, durability, and economic analysis of GGBS-based geopolymer concrete with silica fume under harsh conditions. Sci Rep 14, 31572 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77801-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77801-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Utilization of electronic plastic waste as fine aggregate with and without silica fume in concrete: experimentation and life cycle assessment

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Mechanical, microstructure, durability, and economic assessment of nano titanium dioxide integrated concrete

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Durability and service life prediction of fly ash based geopolymer high performance concrete under extreme environmental conditions

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Ensemble machine learning models for predicting strength of concrete with foundry sand and coal bottom ash as fine aggregate replacements

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Influence of untreated and treated recycled coarse aggregates on engineering properties of slag dolomite geopolymer concrete

Scientific Reports (2025)