Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder exacerbated by obesity. Single Anastomosis Sleeve-Ileal Bypass (SASI) has emerged as a promising metabolic bariatric procedure that combines sleeve gastrectomy and ileal bypass, facilitating substantial weight loss and T2DM remission through restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms. This study aims to evaluate the effects of SASI on T2DM remission, weight loss, and safety in one year follow-up. A retrospective cohort study analyzed 31 patients with obesity and T2DM who underwent SASI. Data collected included demographic characteristics, preoperative and postoperative BMI, HbA1c levels, and bariatric outcomes, including %TWL and T2DM changes. The mean age was 45 years, with a mean preoperative BMI of 40.7 kg/m². One year postoperatively, the mean %EWL was 85.6% and %TWL was 31.7%. T2DM remission was achieved in 24 (77.4%) patients, improvement in 4 (12.9%), and no change in 3 (9.7%). Hypertension improved in 21 (87.5%) patients, with 12 (50%) achieving remission. Significant reductions in BMI and HbA1c levels were observed (p < 0.001). Responders (R) and non-responders (NR) groups showed significant differences in postoperative BMI and %EWL (p = 0.007, p = 0.023). One patient experienced a Clavien-Dindo Grade III complication; no deaths occurred. SASI is an effective and safe procedure for treating T2DM, resulting in significant weight loss and metabolic improvements over a one-year follow-up. SASI seems to be a favorable option for T2DM management in metabolic bariatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder that represents one of the most significant health challenges. The rising epidemic of obesity, a major risk factor for T2DM, necessitates the search for effective treatment methods for both obesity and its related diseases1,2. Metabolic bariatric surgery (MBS) leads to alterations in gastrointestinal anatomy and consequently in changes in gastrointestinal hormones secretion, achieving glycemic control early before weight loss3. Despite the existence of well-known MBS that have a high percentage of T2DM remission, the search continues for the ideal procedure that combines effective weight loss, remission of obesity-related diseases, and minimal long-term complication risks4,5.

A promising method appears to be the Single Anastomosis Sleeve-Ileal Bypass (SASI) - surgery including sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and anastomosis of the prepyloric area with the small intestine. In 2012, Santoro et al. proposed a method that divided the ingested food into two pathways—one anatomically through the duodenum and the other using a gastro-ileal bypass with a Roux-en-Y loop6. Initial reports were promising, and subsequently, Mahdy et al. suggested simplifying the procedure by reducing it to a single anastomosis7. SASI combines elements of two well-established MBS: SG and transit bipartition. SG involves resecting the stomach’s volume, while ileal bypass reroutes a portion of the small intestine. This combination results in significant weight loss and metabolic improvements due to both restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms8,9. Research has demonstrated that SASI not only promotes substantial weight loss but also induces remission of T2DM10,11. The aim of this study is to analyze the effect of SASI on T2DM over a one-year follow-up period in two high-volume centers in European Country. The secondary aim is to evaluate the weight loss and safety of the procedure.

Materials and methods

Study design

It is retrospective cohort study. We analyzed patients who underwent SASI for obesity and T2DM in two bariatric departments. Patients were qualified for surgery according to national and international criteria. All patients gave appropriate consent to perform the procedure. Inclusion criteria for this study were meeting the eligibility criteria for MBS, BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 and suffering from T2DM using oral medicaments or insulin injections. The exclusion criteria was the age below 18 years, malignancy, previous bariatric procedures. Patients with missing or inconsistent data were excluded from the study. The follow up rate is 96,9%. The analysis is in line with STROBE guidelines12.

Ethical considerations

The data were completely anonymized. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The research was approved by the Ethical Committee of Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education (Bioethics Commission Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education Resolution No. 313/2023).

Participants

The database contained demographic characteristics of patients (sex, age, weight before surgery, body mass index (BMI) and information on T2DM and outcomes of bariatric treatment (current weight and BMI, T2DM remission and complications). The postoperative survey was performed during personal visits 12 months after surgery. The manuscript uses the ASMBS guidelines regarding criteria and definitions for the resolution of comorbidities in a group of patients with obesity13. The patients were divided into two groups: responders (R) and non-responders (NR). R were patients who achieved remission of T2DM, while NR were patients with improvement or no changes.

Measurements

Weight loss was reported as a percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) and a percentage of total weight loss (%TWL). Remission of T2DM is a normal measure of glucose metabolism (HbA1c < 6%, fasting blood glucose (FBG) < 100 mg/dL) in the absence of antidiabetic medications. Improvement is statistically significant reduction in HbA1c and FBG not meeting criteria for remission or decrease in antidiabetic medications requirement. No remission is no significant changes in medication intake and laboratory test results13.

These values were calculated according to the following formulas:

%EWL = [(Initial Weight) - (Postop Weight)] / [(Initial Weight) – (Ideal Weight^)] (^ ideal weight is defined by the weight corresponding to a BMI of 25 kg/m213)

%TWL = [(Initial Weight) - (Postop Weight)] / [(Initial Weight)] * 100.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent SASI according to standard technique14. After administering general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a French setup in an anti-Trendelenburg position. A pneumoperitoneum with a pressure of 14 mmHg is. The sleeve was started 6 cm before the pylorus calibrating using a 36 French nasogastric tube. The greater curvature was de-vascularized, and a gastric sleeve was created using a linear stapler. The ileal loop was measured approximately 350 cm proximally to ileocecal valve. Then the 3 cm gastro-ileal anastomosis using a linear stapler was made. The defect was closed with an absorbable self-locking suture. Routinely no drain was left.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted. All data were analysed using Statistica software 13.PL (StatSoft Inc.). The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to confirm the normality of the distribution of continuous variables. Continuous variables were presented as the mean with standard deviation. Student’s t-test was applied for the correlated variables. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

31 patients who underwent SASI in two bariatric centers were analyzed in this study. The mean age was 45 years (± 8.1), the mean preoperative BMI was 40.7 kg/m2 (± 4.2), Table 1.

Weight control and resolution in obesity-related diseases

24 (77.4%) patients had T2DM remission, 4 (12.9%) had improvement in T2DM and 3 (9.7%) had no changes in T2DM. 24 patients (77,4%) had HT before surgery. 12 (50%) patients had remission, 9 (37.5%) had improvement and 3 (12.5%) had no changes in HT one year after surgery. The mean %EWL was 85.6% and the mean TWL% was 31.7% one year after surgery. The postoperative HbA1C lost significantly after the surgery (p < 0.001), Table 2.

Outcomes based on response to SASI

Patients were divided into two groups: responders (R) and nonresponders (NR), Table 3. In group R, patients achieved T2DM remission (n = 24). In group NR patients did not achieved T2DM remission (n = 7). Patients from the R and NR groups did not differ statistically in terms of BMI before surgery, p = 0.096. Patients in NR group were significantly older than patients in R group, p = 0.041. Among the outcomes, statistical significance was observed in correlation with BMI and %EWL one year postoperatively (p = 0.007, p = 0.023, respectively).

Perioperative complications

There were no prolonged LOS or deaths in study group. There was one 30-day Clavien-Dindo Grade III complication. One patient in the PG developed a leak 5 days after surgery. The sewing of perforation was performed with a good outcome.

Discussion

Our study is a retrospective analysis of 31 patients underwent SASI in two major surgical departments. It has been shown that SASI achieves a satisfactory effect in T2DM improvement in short term follow-up. To our knowledge, there are very few studies describing SASI and its metabolic effects, therefore this report seems important for considerations about this procedure.

In our study, the mean %EWL after one year was 85.6 ± 26.6, which is consistent with the results previous studies7,8,9,15,16. Dowgiałło-Gornowicz et al. in their study obtained %EWL of 104.5 ± 27.2 in the group of patients undergoing primary surgery, these values were even higher after 24 and 36 months9. More than 85% of patients in this group were patients with T2DM. Naeni et al. included only patients with T2DM and a BMI > 35 kg/m210. The results presented the level of excessive body weight loss at the level of 60.99 ± 15.69, with the maximum values reaching almost 95. Khalaf et al. compared the results two years after surgery, %EWL was 96.7 ± 5, and after one year 86.9 ± 9.215. It is worth emphasizing that the %EWL after SASI surgery is higher in all studies in which the observation of patients lasts longer than one year.

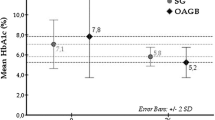

SASI surgery affects the gastrointestinal hormonal system, which contributes to improved glycemic control. Kehagias et al. showed that glycemic control and T2DM remission is mainly due to the increased effect of incretins and specifically GLP-1 based on the hindgut theory17. In the study by Agajami et al. remission for T2DM after 1 year was 93%18, Yildirak et al. reported 83.87%19. In our study group, 24 patients (77.4%) had their diabetes completely resolved, and in 4 (12.9%), the surgery led to improved insulin sensitivity and reduced need for antidiabetic drugs (improvement). The results obtained in our study are slightly worse than in the works of other authors18,19 which may be due to the fact that internists caring for patients did not discontinue oral medications, even though laboratory tests indicated complete remission of the disease. This phenomenon was described by Cummings et al., who drew attention to keeping patients on metformin therapy, even after achieving normoglycemia, using it to prevent relapses, with the hope of cardiovascular benefits independent of glycemia or treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome20. This practice contradicts any definition of T2DM remission (discontinuing all diabetes medications). Unfortunately, there is no established standard in bariatric/metabolic research on how to deal with this problem. Yu et al. analyzed the outcomes of bariatric treatment after SASI, OAGB, and SG21. According to their analysis in 1 year follow-up, SASI was associated with greater weight loss and better improvement in T2DM compared to SG and OAGB20. Suh et al. performed a systematic review comparing SASI and SADI22. Both procedures were similar in weigh loss in one year follow-up. But, SASI procedure had a higher impact on T2DM remission compared to SADI21.

Like any other surgery, SASI surgery carries some risk of complications. However, the reported complication rate after SASI bypass is not higher than that of other malabsorptive procedures16. During the 12-month follow-up in our study, no serious complications, such as deaths or severe nutritional deficiencies, were observed. Reduced risk of deficiency comes from: preservation passage through the pylorus and the length of the common intestinal loop, which in patients included in this study was 350 cm. Emile et al. observed that shorter common limb (250–300 cm) was associated with higher incidence of complications (mainly malnutrition) and worse arterial HT remission11. Wafa et al. published an alarming rate of malnutrition after SASI23. The materials and work methods emphasized that the common loop was 300 cm. This again suggests that leaving such a short loop results in complications and prompts to change the method and perform the anastomosis at least 350 cm from the Bauchin valve. Taking into account the results of our work and other publications based on this technique, it eliminates the possible occurrence of malnutrition while maintaining good bariatric and metabolic effects8,9,10.

Patients undergoing MBS surgery are at risk of deficiency, which depends on the type of surgery. Due to the restrictive nature of the surgery, patients after SG may also be at risk of deficiency, mainly in iron, folate, and vitamin B1224. These deficiencies can be effectively treated by supplementing appropriate ingredients25. Follow-up nutrition is a necessary condition in the postoperative period, especially in the first year after surgery when weight loss, and therefore the risk of malnutrition, are the highest.

SG is associated with the creation of a long line of staples along the stomach and, therefore, potential complications in the form of leakage. The most common place of leakage is the proximal part of the remaining stomach26. Especially in patients with a high BMI, in this area, there are technical difficulties with correctly using the stapler, or in the case of sewing the staple lines, difficulties in tightly sewing this part of the stomach. In this part, the stomach wall has the smallest thickness, which may also be associated with a greater risk of leakage. The gastro-ileal anastomosis leads to lower pressures in the sleeve conduit, which reduces the risk of leakage after SASI. The treatment of choice should be drainage of the gastric pouch and inserting a stent/VACstent into the stomach in the place of leakage26. It’s worth noting the significant role that endoscopic treatment, a testament to the progress in the field of medicine, plays in the treatment of leaks27.

In our study group, HT showed significant improvement soon after the operation, with over three-quarters of the patients experiencing complete resolution. These outcomes align with previous research9,11.

The conclusions from studies on SASI are very promising and make SASI surgery a good alternative to the already established MBS28. Mahdy et al. compared patients after Roux en Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and SASI28. After 12 months %TWL was comparable after both surgeries. There were no differences between surgeries in terms of resolution of comorbidities or complications. The differences concerned the results of laboratory tests regarding postoperative iron levels (higher levels after SASI surgery) and albumin levels (significant decrease after RYGB)28.

Similarly, the potential of SASI surgery is highlighted when compared with SG29. %EWL assessed six months after surgery was similar in both groups. The difference was visible 12 months after surgery; SASI resulted in a higher %EWL after 12 months than SG (72.6 vs. 60.4)29. SASI also had an advantage over SG in the remission of T2DM. (95.8% vs70%)29.

It’s important to note that this study has limitations due to its retrospective design and relatively small study group, which restricts the ability to independently draw comprehensive conclusions or propose recommendations. However, it’s worth mentioning that these cases represent the first experiences with SASI at our centers, where the surgeons are highly experienced, performing over 100 bariatric surgeries annually. Given the learning curve associated with SASI, the results are quite promising. Another limitation is the lack of data regarding the duration of preoperative T2DM and the specific medications that patients were taking.

Conclusions

The results of our study confirmed that SASI surgery is an effective and safe method for treating T2DM, resulting in significant weight loss during the one-year follow-up period. We emphasize that the complications associated with the procedure are minor and underscore the importance of a balanced approach to managing postoperative complications, T2DM, and weight control.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Maggio, C. A. & Pi-Sunyer, F. X. Obesity and type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. ;32:805 – 22, viii. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-8529(03)00071-9 (2003).

Affinati, A. H., Esfandiari, N. H., Oral, E. A. & Kraftson, A. T. <ArticleTitle Language=“En”>Bariatric surgery in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr. Diab Rep. 19, 156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1269-4 (2019).

Lampropoulos, C. et al. Ghrelin, glucagon-like peptide-1, and peptide YY secretion in patients with and without weight regain during long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a cross-sectional study. Prz Menopauzalny 21, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2022.116492 (2022).

Salminen, P. et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss, Comorbidities, and Reflux at 10 Years in Adult Patients With Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 157, 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.2229 (2022).

Peterli, R. et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 319, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.20897 (2018).

Santoro, S. et al. Sleeve gastrectomy with transit bipartition: a potent intervention for metabolic syndrome and obesity. Ann. Surg. 256, 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825370c0 (2012).

Mahdy, T., Wahedi, A. A. & Schou, C. Efficacy of single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass for type-2 diabetic morbid obese patients: Gastric bipartition, a novel metabolic surgery procedure: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 34, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.018 (2016).

Tarnowski, W. et al. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass (SASI): a single-center initial report. Wideochir Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne 17, 365–371. https://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2022.114943 (2022).

Dowgiałło-Gornowicz, N., Waczyński, K., Waczyńska, K. & Lech, P. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass as a primary and revisional procedure: a single-centre experience. Wideochir Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne 18, 510–515. https://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2023.128021 (2023).

Mousavi Naeini, S. M., Toghraee, M. M. & Malekpour Alamdari, N. Safety and Efficacy of Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal (SASI) Bypass Surgery on Obese Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus during a One-Year Follow-up Period: A Single Center Cohort Study. Arch. Iran. Med. 26, 365–369. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2023.55 (2023).

Emile, S. H., Mahdy, T., Schou, C., Kramer, M. & Shikora, S. Systematic review of the outcome of single-anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity with proportion meta-analysis of improvement in diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Surg. 92, 106024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106024 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 12, 1495–1499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 (2014).

Brethauer, A. S. et al. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. ;11:489–506. doi: 0.1016/j.soard.2015.02.003 (2015).

Bhandari, M., Fobi, M. A. L., Buchwald, J. N. & Bariatric Metabolic Surgery Standardization (BMSS). Working Group:. Standardization of Bariatric Metabolic Procedures: World Consensus Meeting Statement. Obes. Surg. 29, 309–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04032-x (2019).

Khalaf, M. & Hamed, H. Single-Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal (SASI) Bypass: Hopes and Concerns after a Two-Year Follow-up. Obes. Surg. 31, 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04945-y (2021).

Mahdy, T., Gado, W., Alwahidi, A., Schou, C. & Emile, S. H. Sleeve Gastrectomy, One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass (OAGB), and Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal (SASI) Bypass in Treatment of Morbid Obesity: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Obes. Surg. 31, 1579–1589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05159-y (2021).

Kehagias, D. et al. Diabetes Remission After LRYGBP With and Without Fundus Resection: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Obes. Surg. 33, 3373–3382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06857-z (2023).

Aghajani, E., Schou, C., Gislason, H. & Nergaard, B. J. Mid-term outcomes after single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass in treatment of morbid obesity. Surg. Endosc 37, 6220–6227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-023-10112-y (2023).

Yildirak, M. K., Şişik, A. & Demirpolat, M. T. Comparison of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal Bypass in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Remission Using International Criteria. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. A 33, 768–775. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2023.0112 (2023).

Cummings, D. E. & Cohen, R. V. Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery to Treat Type 2 Diabetes in Patients With a BMI < 35 kg/m2. Diabetes Care. 39, 924–933. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0350 (2016).

Yu, H. et al. Analysis of the efficacy of sleeve gastrectomy, one-anastomosis gastric bypass, and single-anastomosis sleeve ileal bypass in the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 14, 5069. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54949-2 (2024).

Suh, H. R. et al. Outcomes of single anastomosis duodeno ileal bypass and single anastomosis stomach ileal bypass for type II diabetes: a systematic review. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/17446651.2023.2218919 (2023).

Wafa, A., Bashir, A., Cohen, R. V. & Haddad, A. The Alarming Rate of Malnutrition after Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal Bypass. A single Centre Experience. Obes. Surg. 34, 1742–1747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-024-07192-7 (2024).

Gasmi, A. et al. Micronutrients deficiences in patients after bariatric surgery. Eur. J. Nutr. 61, 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02619-8 (2022).

Ben-Porat, T. et al. Nutritional deficiencies four years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy-are supplements required for a lifetime? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 13, 1138–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2017.02.021 (2017).

Manos, T. et al. Leak After Sleeve Gastrectomy: Updated Algorithm of Treatment. Obes. Surg. 31, 4861–4867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05656-8 (2021).

Oshiro, T. et al. Treatments for Staple Line Leakage after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. J. Clin. Med. 12, 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103495 (2023).

Mahdy, T. et al. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass with Long Biliopancreatic Limb Compared to Single Anastomosis Sleeve Ileal (SASI) Bypass in Treatment of Morbid Obesity. Obes. Surg. 31, 3615–3622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05457-z (2021).

Emile, S. H. et al. Single anastomosis sleeve ileal (SASI) bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy: a case-matched multicenter study. Surg. Endosc 35, 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07430-w (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J., N.D-G., WT drafting of the manuscript, participation in operations (operational team), preparation / collection of patient data analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published, J.P, A.B., K.B., E.K. P.L. drafting of the manuscript, participation in operations (operational team), final approval of the version to be published P.J., M.W., A.K. preoperative and 12 months postoperative diagnosis of patients, preparation / collection of patient data, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Bioethics Commission Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education Resolution No. 313/2023.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participant included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaworski, P., Dowgiałło-Gornowicz, N., Parkitna, J. et al. Efficacy of single anastomosis sleeve-ileal bypass in weight control and resolution of type 2 diabetes mellitus – a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 14, 26360 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77869-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77869-7