Abstract

The mechanical deformation of coals occurring extensively during the geological period (tectonically deformed coals) can directly alter their pore structures and then the storage of coalbed methane. This study in-situ investigated the effects of different mechanical deformations on the ultramicropore structure and the methane adsorption of coal molecules using molecular simulations. The results show that the shear deformation (< 0.23 GPa) of coals was much easier than the compression (~ 20 GPa). Further, the shear deformation can increase the void fraction (200%) and the surface area (30%) of coal molecules, comparing to the reduction of them by the compressive deformation. Accordingly, compression is not benefited to the methane storage (only remaining 14-22% adsorption amount). While, the shear deformation of coals can increase the methane adsorption amount (reaching 42–50 mmol/g). The ~ 7.5 Å is a key pore size to evaluate the effect of the shear deformation on the methane adsorption amount. Also, the adsorption sites for methane depends on the deformation mode of coals (compression: heteroatoms; shear: C atoms). Overall, the strained Wiser (bituminous, medium-rank) coal shows relatively superiority in the methane storage, while the methane adsorption of Wender (lignite, low-rank) coal is much more sensitive to the mechanical strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal’s geomechanical response has been paid more and more attentions owing to its influences in the coal mining process, coalbed methane (CBM) utilization, and related safety issues1. Especially, the underground geological stress can induce the formation of the tectonically deformed coals (TDCs), which are often prone to CBM outbursts2. Understanding of TDCs’ microstructure evolution is quite important in low-risk and efficient CBM exploitation3,4.

Coal, owing to its complex molecule structure5,6,7, is actually a heterogeneous polymeric material with the properties of porous media. Due to the flexibility of the organic molecules, the pore structure of coal can be significantly altered under the action of tectonic and thermal stress8,9,10,11,12. Many factors, including the character of the tectonic stress (type and intensity) and the mechanical properties of coals, has been previously investigated to clarify the pore structure evolution of coals. Among various types of stress, only tectonically shear stress shows positive influences in the porosity and specific surface area (SSA) of coals3,13. Regarding the deformation intensity, ductile deformation, instead of brittle deformation, can bring a noticeable increase of SSA and total pore volume (TPV) of coals13. Also, intensive deformation can result in the rupture and the orientation changes of fused aromatic rings of coals, as well as the generation of gas and free radicals14,15,16,17,18. The elastic modulus of coals is another factor that affects the internal pore structure of coals. Soft coal (low elastic modulus) shows greater SSA and TPV than hard coal (high elastic modulus)1,19.

The purpose of investigating the coals’ pore structure is to understand the methane sorption capacity and then CBM outburst20. Both of confined and adsorbed methane has been considered inside the pore of TDCs21,22. Free methane content is primarily influenced by macropore (> 100 nm), whereas ultramicropores (< 2 nm) provide the main adsorption sites for methane23. With the increasing of the coal deformation intensity, the proportion of ultramicropore rises. At the ductile deformation stage, ultramicropores occupy the vast majority of TPV and SSA, resulting in enhanced adsorption capacity of methane3,4,23. Although enormous investigations on the pore structure and the methane storage of TDCs have been performed, most of them still used free or semi-free deformation in lab3,13,21,22. The underground confined condition is actually the main character of TDCs. Especially, the adsorbed methane within confined TDCs is relatively stable and dominates the final stage of CBM outburst and exploitation14,15,16,17. However, it is still a challenge for current experimental techniques to conduct continuous and in-situ investigations of the ultramicropore structure and the methane adsorption evolution of confined TDCs.

In this study, we employed molecular simulations to in-situ and comprehensively investigate the pore structure evolution and the methane adsorption of confined TDCs. The reactive force field was used to reliably capture the bond breakage and formation during the intensive deformation of coals. Two deformation modes (compression and shear) were exerted on different types of confined coals. The porosity, the surface area, and the pore size distribution of confined TDCs have been detailed analysed. And their influences in the methane adsorption capacity were clarified. The radial distribution functions revealed the main adsorption sites for methane inside confined TDCs with different deformation modes and intensities. The research shows a certain guiding significance for understanding the TDCs pore structure evolution and their methane adsorption capacity under different in-situ and confined deformation conditions.

Computational method

Three coals (Wender, Hatcher, and Wiser) were chosen for this study (Fig. 1 and Table S1)24,25. Wender and Hatcher coal types were low-ranked coal, whereas Wiser was medium-ranked coal. The number of atoms and molecular mass increased from Wender to Hatcher, to Wiser coal. Only one type of heteroatom (O) existed in the Wender and Hatcher coal molecule, whereas three types of heteroatom (O, N, and S) are in the Wiser coal. The geometry optimization of a single molecule of coals was performed using density functional theory (DFT) calculation and employing Dmol3code26. The exchange-correlation energy was described by the PW91 functional under a generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PW91). DFT Semi-core pseudo-potentials for all atoms were used. Double-numeric basis with polarization functions (DNP) was used for all atoms. OBS method was used for dispersion corrections. All optimized molecules are shown in Fig. S1.

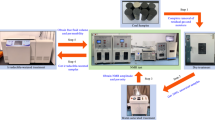

Eight molecules for each coal after DFT optimization were loaded into the simulation box. LAMMPS software (http://lammps.sandia.gov)27was employed to perform 21 molecular dynamic (MD) steps with various temperature (300–600 K) and pressure (1–50000 bar) values proposed by Hofmann et al.28. Then, the amorphous structures of the studied coals were prepared. The density of Wender, Hatcher, and Wiser coals was determined as 1.33, 1.26, and 1.35 g/cm3, respectively. In a stepwise manner, an external compressive and shearing force was applied (Fig. 2). For each step, the uniform strain increment was set to ~ 2%, and the relaxation time at a constant temperature was set to 10 ps. Another 20 ps run was performed to obtain the equilibrium configurations (1000 frames) for the pore structure analysis and the methane adsorption. All obtained results from every strain step were based on the 1000 frames of the equilibrium configurations.

The reactive force field ReaxFF was derived from the quantum mechanical results, which included the bond-order dependence and were used to describe bond breaking and forming29. ReaxFF MDs is a reliable method to investigate the mechanical deformation of coals, involving the ring reorientation and the bond rearrangement during elastic and ductile deformation15,18,19,25. ReaxFF parameters developed by Fidel Castro-Marcano et al30. for the combustion of coals were used in this study. The time step was set to 0.2 fs, which was sufficient to satisfy the requirement of ReaxFF model. Nosé-Hoover thermostat or barostat was employed to equilibrate the system. Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) were applied along the three main coordinate directions.

Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations were carried out to compute the methane adsorption isotherms in the deformed coals by employing the Complex Adsorption and Diffusion Simulation Suite (CADSS) code31. For each strain step, 1000 frames of equilibrium configurations were employed to compute the average adsorption amount of methane. The fugacities for methane at a given thermodynamic condition were computed using the Peng-Robinson equation of state. For each state point, 108 Monte Carlo steps were used for both equilibration and production runs. The methane/coal and methane/methane interactions were treated using a van der Waals contribution with a cut-off of 12 Å. The Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential parameters for the atoms of coal molecules were derived from the universal force field (UFF). Single-site spherical Lennard-Jones 12 − 6 potential taken from the TraPPE force field was used to model methane molecules. Lorentz-Berthelot (LB) combination rules were used to calculate the cross LJ potential parameters.

Results and discussion

Figure 3 shows the stress-strain curves of lignite, subbituminous, and bituminous coals. The compressive stress nonlinearly increases with increasing strain (~ 20 GPa at 40% strain) and no elastic failure was observed (Fig. 3a). This was in contrast to the uniaxial compression tests conducted in the lab, where the obvious peak stress has a boundary between brittle and ductile deformation32,33. In general, mechanical deformation is a process of energy storage, and failure corresponds to the release of the deformation energy. For coal seams, the underground geometry can inhibit energy release by confining the deformation. Therefore, the stress-strain curves of underground coals are different from that of free coals in conventional tests. Current computational model employs a fixed wall to simulate the confining effect (Fig. 3, insets).

Compared to compression, the shear deformation of coals is easy to be performed, showing much lower stress (< 0.23 GPa) (Fig. 3b). It should be noted that the negative stresses appear in the low strain of Wender and Wiser model. Actually, the further deformation can be benefited from the unreleased internal stress. Especially, the contribution of the internal stress is more significant in shear due to the low deformation stress. The shear stress-strain curves for the three studied coals display an obvious fluctuation character, indicating the coexistence of mechanical energy storage and release. Current shear deformation performs shear-tensile coupling using a fixed wall.

Importantly, there are two notable points: Firstly, the medium-ranked coal (Wiser) presents relatively high deformation stress under the same strain, whereas the Hatcher coal is soft, especially at the ductile stage. Secondly, under the current strain range (0–40%), the mechanochemical reactions of coals are not observed. Therefore, the isolated deformation effect on the ultramicropore structure and the methane adsorption of coals were obtained.

Figure 4 shows the variation of the void fraction and surface area of the studied coals under deformation. The computed surface area (probe molecule: N2) of the initial Wender (8.8 m2/g) and Wiser (8.4 m2/g) coals agrees well with the experimental values (0.2–35.0 m2/g)34. And the computed surface area of Hatcher (52.3 m2/g) is a little overestimation. As the compressive strain increased, both the void fraction and the surface area of coals decreased (Fig. 4a). They can even vanish at the compressive strain of 40%. A nearly linear reduction of the void fraction was observed, where the surface area decreased slowly and fast at the low ( < ~ 20%) and high ( > ~ 20%) strain range, respectively.

A completely different variation trend of the void fraction and the surface area of coals under shear deformation was observed (Fig. 4b). The void fraction of different coals increased linearly with increasing shear strain. Almost 3 times of the void fraction can be obtained at the shear strain of 40%, which agrees well with the experimental result of tectonically shear coals (3‒8 times more porosity)3. However, the surface area displayed two parts of the variation trend: initially increasing and later decreasing. A peak of the surface area occurred at the shear strain of 10% (Wiser), 14% (Hatcher: ), and 18% (Wender). This indicated that changes in the void fraction were not always positively correlated with the surface area. The growing void corresponded to the reduced surface area of the coals when the shear strain was above 20% (Fig. 4b). This was related to the variation of pore size within coals, which will be discussed.

Similar variation trends of the void fraction and the surface area of the studied coals under deformation were observed. Among the studied coals, there was only a slight difference in their structure evolution. Wender coal showed a relatively fast and slow reduction of the surface area in ductile compression and shear deformation, respectively. However, the void fraction and the surface area of the medium-ranked coal (Wiser) were sensitive to shear loading.

Figure 5shows the computed methane uptake and the pore size distribution of the initial coals. The saturation adsorption amount of methane in current models is around 3–14 mmol/g, which is larger than the experimental value (0.3–1.8 mmol/g)34. The enhanced adsorption can be attributed to the dominated ultramicropore structure in current models. Compared to Wender and Wiser coal, Hatcher coal could adsorb more methane molecules under various temperatures (Fig. 5a). The saturated adsorption amount of the initial Hatcher coal was almost 2 and 4 times larger than that of other initial coals. This was achieved via examination of the pore size distribution of different coals (Fig. 5b). The kinetic diameter of a methane molecule is ~ 3.8 Å. Hence, only pores larger than ~ 3.8 Å could be used to evaluate the methane uptake capability. Three peaks were observed for the pore size distribution of Hatcher coal, two of which were larger than 3.8 Å. Comparatively, most of the pores related to Wender and Wiser coals were < 3.8 Å. Thus, more methane molecules can be adsorbed by the internal surface of Hatcher coal molecules, which then show excellent adsorption amount of methane. It should be noted that only the ultramicropores exist in current coal models and thus the computed pore size is much smaller than the experimental value (19–107 Å)34.

The pressure displayed in Fig. 5a is also called the injection pressure29. Figure 6a‒c shows the compressive strain effect on the methane uptake of the studied coals under different injection pressures. At the same methane injection pressure but under different strains, the amount of methane adsorption decreased with increasing strain. The higher the methane injection pressure, the more rapidly the amount of methane adsorption decreased with increasing strain. Once the compressive strain reached 4%, only ~ 14% adsorption amount can be remained at 45 Bar for Wender coal. Overall, the methane uptake amount of Wender coal was reduced to ~ 90% (Fig. S2). This was attributed to the rapid shrinkage of the coal’s pore size (Fig. 6d). The Wiser and Hatcher coals showed relatively slow shrinkage of the pore, resulting in a smaller decrease of methane adsorption with increasing compressive strain. The ~ 22% adsorption amount can be remained even at 45 Bar and higher strain (14%).

As the shear strain increased (< 10%), the methane uptake amount of Wender and Wiser coals slowly increased under high injection pressure (Fig. 7a‒c). As the shear strain continuously increased, the methane adsorption showed considerable enhancement. Once the shear strain was > 30%, the methane uptake amount was almost unchanged for Wiser coal, but a small decline was observed for Wender coal. The main difference in methane adsorption among the studied coals was that Hatcher coal showed a slight reduction in adsorption at 10% shear strain.

The initial adsorption amount of Wender and Wiser coals was much smaller than that of Hatcher coal (3.53 and 6.84 vs. 13.57 mmol/g at 45 Bar). It was found that 40% shear strain could promote Wiser coal to adsorb more methane than Hatcher coal (50.38 vs. 42.29 mmol/g at 45 Bar). Even Wender coal possessed the same level of methane adsorption capacity (42.50 mmol/g at 45 Bar) as Hatcher coal. Regarding the methane uptake variation, Wender coal was much more sensitive to shear strain (Fig. S2).

The pore size of the studied coals increased with increasing shear strain (Fig. 7d). Especially, Wiser coal’s pores showed a relatively rapidly increasing trend. After ~ 10% shear strain, Wiser coal possessed larger pores than Hatcher coal. Figure 7d (shaded area) corresponds to the pore size range where a sharp increase in methane uptake amount occurred. Although the lower limit of the suitable pore size range for methane adsorption was different, the upper pore size of ~ 7.5 Å was the same for all coals. Wender (~ 42 mmol/g) and Wiser (~ 44 mmol/g) coals possessed comparable or more methane adsorption capability than Hatcher (~ 38 mmol/g) coal with the pore size of 7.5 Å. Once the pore size of coals was > ~ 7.5 Å, the methane uptake amount remained unchanged and even showed a slight reduction. Additionally, large pores enhanced coals’ porosity, instead of the surface area (Fig. 4b).

As the strain of coals increases, the saturated adsorption amount of methane linearly decreases in compressed coals (Fig. 8a), while nonlinearly increases in sheared coals (Fig. 8b). The relation between the saturated adsorption and the strain can be fitted by Equ. (1) and (2). The reduction of the saturated adsorption here agrees well with the reported results in triaxial compression of coals35.

Where as is the saturated adsorption of methane, dc is the compressive strain, and b1 = 6.092, b2 = -0.397.

Where ds is the shear strain, and n1 = 3.130, n2 = 49.778, s0 = 14.145, and s1 = 5.330.

The adsorption sites on methane in coals were analyzed by the radial distribution functions (RDFs) (Fig. 9 and S3‒4). Within the raw coal, the methane preferred to approach the heteroatoms (O, N, and S) of Wiser coal (Fig. 9a). RDF peaks at 2.05 Å and 3.95 Å indicated the strong and weak adsorption of methane, respectively. Additionally, the heteroatom (O) of Wender coal was responsible for the main adsorption of methane, which was evident by the peak at 3.15 Å (Fig. S3a). However, Hatcher coal showed a greater peak intensity for C-methane pair than that for O-methane pair (Fig. S4a). This could be attributed to the high ratio of C to O (96:12) in Hatcher coal molecule, compared to the ratio (48:12) in Wender coal molecule.

Compressive deformation resulted in the separation between methane and O atoms of Wiser coal molecule. Hence, the main adsorption sites of methane were close to the N and S atoms of Wiser coal (Fig. 9b). Within the compressed Hatcher coal, O-methane pair showed a stronger RDF peak than C-methane pair (Fig. S4b). Therefore, O atoms provided the main adsorption for methane inside the compressed Hatcher coal.

Unlike RDFs variation under compression, the shear deformation could enhance the proximity of C atoms in coals to methane molecules (Fig. 9c, S3b, and S4c). For Wiser coal, the second intense peak at 4.15 Å was related to O-methane pair. Furthermore, methane molecules were hindered in their approach to other heteroatoms (N and S) of the Wiser coal. RDF peak located at 4.15 Å indicated weak host-guest interactions.

The strongest peak intensity ratio of C-methane to O-methane (IC/IO) was used to investigate the variation of the adsorption site within the deformed coal (Fig. 9c). The compression could lead to the reduction of IC/IO (Fig. S5), while the ratio values increased with increasing shear strain (Fig. 8d). Hence, compressive deformation could induce the transference of the main adsorption sites of methane from C atoms to the heteroatoms of the coal molecule. However, shear deformation enhanced the contribution of C atoms of coal molecules to methane adsorption.

Our study showed that the adsorption sites of methane in coal changed via mechanical deformation. Both the geometrical variation and activated sites was involved here for methane uptake. When the pores were larger for sheared coal, more C atoms as active sites were present for methane adsorption. Among the studied coals, Hatcher coal adsorption sites of methane were highly sensitive to deformation strain.

Based on the above analysis, the appropriate shear deformation (pore size < ~ 7.5 Å) of coals could reduce the risk of adsorbed methane outburst, owing to the enhanced capability of methane adsorption. The compressive deformation of coals reduces the pore size and expels the methane molecules, implying a preferential gas outburst. It should be noted that the adsorbed methane was the resource of the outburst. In the area of engineering, coals and the generated gas outbursts in TDCs must be considered, where the shear zone of coals was considered high risk. Current simulation results are suitable for understanding the last stage of CBM outburst and exploitation, where the adsorbed methane is dominated. Thus, the compressive deformation, instead of the shear, is favorable for completely CBM exploitation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the deformation effects on the ultramicropore structure and the methane adsorption of different tectonically deformed coals were investigated by employing the reactive force field molecular dynamic simulations. The obtained results showed that the shear deformation (< 0.23 GPa stress) of coals was much easier than the compression (~ 20 GPa stress). Both the void fraction and the surface area of coals could be reduced by compression (almost no void at the strain of 40%), while the shear deformation increased these factors (200% and 30% rising of the void fraction and the surface area respectively). As the compressive strain increased, the amount of methane adsorption decreased, especially under high injection pressure (only remaining ~ 14% adsorption amount at 45 Bar and 4% compressive strain of lignite Wender coal). Wiser (bituminous, medium-rank) and Hatcher (subbituminous, low-rank) coals showed relatively slow shrinkage of the pores, hence, a minor decrease in methane adsorption under compression (remaining ~ 22% adsorption amount at 45 Bar and 14% compressive strain). The shear deformation of coals increased the pore size and the methane adsorption below the pore size of ~ 7.5 Å. Above this size, the methane uptake amount remained unchanged or slightly reduced. Wender (~ 43 mmol/g) and Wiser (~ 50 mmol/g) coals possessed comparable or more methane adsorption capability than Hatcher (~ 42 mmol/g) coal with the pore size of 7.5 Å. The heteroatoms of coals were the main adsorption sites for methane under compression, while C atoms were the main active sites for methane adsorption in the sheared coals. The current study clarified the contribution of the mechanical deformation to the ultramicropore structure and the methane adsorption of tectonically deformed coals, which was important in the atomic-level understanding of the CBM outburst and exploitation in TDCs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ullah, B. et al. Experimental analysis of pore structure and fractal characteristics of soft and hard coals with same coalification. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9 (1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00530-z (2022).

Wang, C. & Cheng, Y. Role of coal deformation energy in coal and gas outburst: a review. Fuel. 332, 126019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126019 (2023).

Li, H. & Ogawa, Y. Pore structure of sheared coals and related coalbed methane. Environ. Geol. 40 (11), 1455–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002540100339 (2001).

Ren, J. et al. The influence mechanism of Pore structure of tectonically deformed coal on the Adsorption and Desorption Hysteresis. Front. Earth Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.841353 (2022).

Balaeva, Y. S., Kaftan, Y. S., Miroshnichenko, D. V. & Kotliarov, E. I. Influence of Coal Properties on the Gross Calorific Value and moisture-holding capacity. Coke Chem. 61 (1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1068364X18010039 (2018).

Pyshyev, S., Prysiazhnyi, Y., Shved, M., Kułażyński, M. & Miroshnichenko, D. Effect of hydrodynamic parameters on the oxidative desulphurisation of low rank coal. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 5 (2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0205-6 (2018).

Miroshnichenko, D. et al. Effect of the quality indices of coal on its grindability. Min. Miner. Deposits 16(4), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.33271/mining16.04.046 (2022).

Yu, S., Bo, J., Vandeginste, V. & Mathews, J. P. Deformation-related coalification: Significance for deformation within shallow crust. Int. J. Coal. Geol. 256, 103999. (2022)

Pan, J. et al. Micro-nano-scale pore stimulation of coalbed methane reservoirs caused by hydraulic fracturing experiments. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 214, 110512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110512 (2022).

Li, W., Jiang, B. & Zhu, Y. M. Impact of tectonic deformation on coal methane adsorption capacity. Adsorp Sci. Technol. 37 (9–10), 698–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263617419878541 (2019).

Abdulsalam, J. et al. Optimization of porous carbons for methane adsorption from South African coal wastes. Int. J. Coal Prep Util. 43 (2), 264–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392699.2022.2040493 (2023).

Abdulsalam, J., Onifade, M., Bada, S., Mulopo, J. & Genc, B. The spontaneous Combustion of chemically activated carbons from South African coal Waste. Combust. Sci. Technol. 194 (10), 2025–2041. https://doi.org/10.1080/00102202.2020.1854747 (2022).

Guo, X., Huan, X. & Huan, H. Structural Characteristics of Deformed Coals with different deformation degrees and their effects on Gas Adsorption. Energy Fuels. 31 (12), 13374–13381. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02515 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Mechanolysis mechanisms of the fused aromatic rings of anthracite coal under shear stress. Fuel. 253, 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.05.117 (2019).

Wang, J., Hou, Q., Zeng, F. & Guo, G. J. Gas generation mechanisms of bituminous coal under shear stress based on ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel. 298, 120240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120240 (2021).

Wang, J., Hou, Q., Zeng, F. & Guo, G. J. Stress sensitivity for the occurrence of Coalbed Gas outbursts: a reactive Force Field Molecular Dynamics Study. Energy Fuels. 35 (7), 5801–5807. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c04201 (2021).

Wan, X., Yang, Y., Jia, B. & Pan, J. Simulation of Gas Production mechanisms in Shear deformation of medium-rank coal. ACS Omega. 7 (1), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c04739 (2022).

Liu, H., Song, Y. & Du, Z. Molecular dynamics simulation of shear friction process in tectonically deformed coal. Front. Earth Sci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1030501 (2023).

He, H., Wang, K., Pan, J., Wang, X. & Wang, Z. Characteristics of coal porosity changes before and after Triaxial Compression Shear Deformation under different confining pressures. ACS Omega. 7 (19), 16728–16739. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c01269 (2022).

Cheng, G., Jiang, B., Li, M., Liu, J. & Li, F. Effects of pore structure on methane adsorption behavior of ductile tectonically deformed coals: an inspiration to coalbed methane exploitation in structurally complex area. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 74, 103083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2019.103083 (2020).

Lu, G., Wei, C., Wang, J. & Meng, R. Soh Tamehe, L. Influence of pore structure and surface free energy on the contents of adsorbed and free methane in tectonically deformed coal. Fuel. 285, 119087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119087 (2021).

Zhang, K., Meng, Z., Liu, S., Hao, H. & Chen, T. Laboratory investigation on pore characteristics of coals with consideration of various tectonic deformations. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 91, 103960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2021.103960 (2021).

Hou, Q. et al. Structure and coalbed methane occurrence in tectonically deformed coals. Sci. China Earth Sci. 55 (11), 1755–1763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-012-4493-1 (2012).

Mathews, J. P. & Chaffee, A. L. The molecular representations of coal – a review. Fuel. 96, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.11.025 (2012).

Xia, Y., Zhang, R., Cao, Y., Xing, Y. & Gui, X. Role of molecular simulation in understanding the mechanism of low-rank coal flotation: a review. Fuel. 262, 116535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116535 (2020).

Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 113 (18), 7756–7764. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1316015 (2000).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comp. Phys. Comm. 271, 108171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2021.108171 (2022).

Hofmann, D., Fritz, L., Ulbrich, J., Schepers, C. & Böhning, M. Detailed-atomistic molecular modeling of small molecule diffusion and solution processes in polymeric membrane materials. Macromol. Theory Simul. 9 (6), 293–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3919(20000701)9:6<293::AID-MATS293>3.0.CO;2-1 (2000).

van Duin, A. C. T., Dasgupta, S., Lorant, F. & Goddard, W. A. ReaxFF: a reactive force field for hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A. 105 (41), 9396–9409. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp004368u (2001).

Castro-Marcano, F., Kamat, A. M., Russo, M. F., van Duin, A. C. T. & Mathews, J. P. Combustion of an Illinois 6 coal char simulated using an atomistic char representation and the ReaxFF reactive force field. Combust. Flame. 159 (3), 1272–1285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.10.022 (2012).

Yang, Q. & Zhong, C. Molecular Simulation of Carbon Dioxide/Methane/Hydrogen mixture Adsorption in Metal – Organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110 (36), 17776–17783. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp062723w (2006).

Gong, F., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Pan, J. & Luo, S. A new criterion of coal burst proneness based on the residual elastic energy index. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31 (4), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.04.001 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Numerical Investigation of Relationship between Bursting Proneness and Mechanical Parameters of Coal. Shock Vib. 2021(1), 9928168. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9928168 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. A comparative evaluation of coal specific surface area by CO2 and N2 adsorption and its influence on CH4 adsorption capacity at different pore sizes. Fuel. 183, 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.06.076 (2016).

Fang, S. et al. Evolution of pore characteristics and methane adsorption characteristics of Nanshan 1/3 coking coal under different stresses. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 3117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07118-2 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Qinchuangyuan “Scientist + Engineer” Team Development Program of the Shaanxi Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2024QCY-KXJ-053), and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2023-JC-YB-371).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Longgui Peng: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Huanquan Chen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation,. Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Fuxing Chen: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Jianye Yang: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Bin Zheng: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, L., Cheng, H., Chen, F. et al. Exploring the ultramicropore structure evolution and the methane adsorption of tectonically deformed coals in molecular terms. Sci Rep 14, 26316 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78007-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78007-z