Abstract

In the present study, the photocatalytic performance of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite was investigated through the photodegradation of Acid Blue 113 (AB113) dye under ultraviolet light exposure. TiO2 and ZnS-based nanocomposites suffer from relatively wide bandgap energy and low adsorption capacity which limit their photocatalytic applications. These problems can be suppressed by modifying the surface of nanocomposite particles by the non-thermal plasma. Herein, surface modification of the ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite was performed using a dielectric-barrier discharge plasma under nitrogen (N2) and tetrafluoromethane (CF4) gases. The characteristics of the plasma-treated nanocomposites were evaluated by XRD, FTIR, Raman, FESEM, EDS, BET, BJH, and DRS analyses. According to the results, by applying plasma treatment, cation and anion vacancies are produced that reduces the band gap energy of the photocatalyst hence improves its performance. The results indicate that the photocatalytic efficiency of the N2-plasma-treated nanocatalyst has been almost two times higher than that of the untreated ZnS/TiO2. It was found that after 25 min of UV irradiation, the AB113 was almost completely degraded in the presence of N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite (about 95%), whereas, it was degraded by 64% and 46% in the presence of CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 and untreated ZnS/TiO2, respectively. This study presents a new approach to designing cost-effective plasma-treated photocatalysts to degrade organic contaminants in wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wastes from industrial and agricultural wastewater are very hazardous to human beings and can seriously damage different ecosystems1,2,3. To solve this problem, photocatalysts could provide a promising approach to degrade organic pollutants due to their low cost, biostability, nontoxic, and harmless properties4,5. Photocatalysis can be defined as the chemical reaction process involving light and a catalyst6,7,8. Over the last few years, significant progress has been made in the advancement of heterojunction photocatalysts aimed at enhancing their catalytic effectiveness. This has been achieved by generating intermediate states between the valence and conduction bands using external impurities9. Creating a heterojunction structure between two semiconductors, like ZnS and TiO2, can enhance the separation and movement of electron-hole pairs generated by light10,11. In this regard, various UV-responsive TiO2-based catalysts such as ZnO/TiO212, CdS/TiO213, WO3/TiO214, and ZnS/TiO215,16 have been fabricated and used as photocatalysts. The ZnS/TiO2photocatalyst demonstrates improved photostability and enhanced performance compared to its individual components17,18,19. However, TiO2-based composites suffer from relatively wide bandgap energy and low adsorption capacity which limits their photocatalytic applications20,21,22,23. Numerous researchers have endeavored to improve the performance of these nanocomposites by reducing the bandgap, increasing charge separation, and refining adsorption capacity through various strategies23,24,25.

Plasma catalysis is a growing field of engineering plasma that involves the usage of non-thermal plasma in combination with a catalyst to enhance the processing of input gas streams on catalytic surfaces26,27,28. Non-thermal plasma contains various chemical reactive species, including •OH, O2−, H2O2, and O3, which are highly efficient in oxidizing organic compounds29,30. These species can interact with the catalyst surface31,32. Moreover, plasma can generate beneficial physical phenomena like UV-light emission and strong electric fields, which can aid in the breakdown and elimination of contaminants33,34,35,36. Due to the significant impact of plasma on the surface condition of the catalyst, it is evident that the catalyst function will be modified37. Because of large fluxes of plasma species, employing plasma on the surface of the catalyst is able to give rise to important alterations in its structure and morphology leading to catalyst dispersion38. In this regard, the integration of nitrogen and/or fluorine-based plasma with catalysts is one of the effective methods for enhancing photocatalytic performance. This process can be implemented by plasma nitriding and/or surface fluorination using nitrogen and/or fluorine-based plasma via a dielectric-barrier discharge (DBD) plasma reactor39,40,41,42,43. The N- and/or F-doping species lead to a narrower bandgap and more noticeable light-absorbing ability40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Among the fluorocarbon plasmas, tetrafluoromethane (CF4) is chosen as a non-toxic source of reactive F-species. The key effects of N2 and CF4plasma on the catalyst surface are to alter the catalyst properties, including morphology and pore volume, and boost the activity of the catalyst47,48.

This research assessed the photocatalytic effectiveness of plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites by examining their ability to degrade Acid Blue 113 (AB113) under UV light exposure. Surface modification of the nanocomposites was performed by a low-pressure DBD plasma reactor under N2 and CF4 gases. To our knowledge, no report about the plasma surface modification of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite has been presented in the literature yet. This study served to highlight the potential of plasma-treated photocatalysts for applications related to the restoration of environment.

Experimental section

Chemicals and catalyst preparation

In this work, the pure zinc sulfide (ZnS) and ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite were synthesized by the hydrothermal method as described below. We used the thioacetamide (C2H5NS), ethylenediamine, zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O), carbon disulfide (CS2), ethanol, acetone, and TiO2 as precursors. Nano-sized anatase TiO2 powder, with a diameter of less than 25 nm and a purity of over 99%, was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Synthesis of ZnS photocatalyst

Pure ZnS nanoparticles were synthesized using thioacetamide (C2H5NS) and zinc nitrate as precursors. 0.38 g of thioacetamide was mixed with a solution containing 1.5 g of zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn (NO3)2·6H2O) in 37.5 mL of ethanol and then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. After this step, the solution was shifted to a 100 mL autoclave. The autoclave was heated in the oven at 120◦C for 5 h and subsequently allowed to attain room temperature. The prepared sample was retrieved through centrifugation and then rinsed thrice with distilled water and ethanol. The resultant product was placed in the oven for a final drying process at 60 °C for 10 h.

ZnS/TiO2 photocatalyst synthesis

The synthesis of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite involved the combination of zinc diethyldithiocarbamate and the addition of ZnCl2·4H2O (6.5 mmol, 1.36 g) in 50 mL water, followed with stirring the reaction mixture at room temperature. Then, ethylenediamine (20 mmol, 1.33 mL) and CS2 (13.5 mmol, 0.8 mL) were added to the suspension of ZnCl2·4H2O in water. After mixing the mixture for 2 h, a quantity of 2.5 mL of ethylenediamine was incrementally introduced into a solution of acetone (47.5 mL) containing zinc dithiocarbamate complex and 0.125 g of TiO2nanoparticles49. After refluxing for 4 h, the solid was separated from the liquid phase through centrifugation, followed by washing with acetone and drying at ambient temperature for 24 h.

Plasma surface modification

In this work, a homemade DBD reactor has been used, and a detailed description of that is given in Refs39,50,51. The DBD plasma chamber is made of stainless steel, and the chamber volume is about 6200 cm3. The two electrodes in the DBD are made of stainless-steel plate with a diameter of 8 cm and thickness 2 cm. Both electrodes are covered by quartz dielectrics with thicknesses of 10 mm. The gap between the two dielectrics was regulated to 8 mm. The upper electrode is connected to a high-voltage power supply (14 kV peak-to-peak), while the lower electrode is grounded. The nano-powders were placed inside a thin plastic petri dish (with a diameter of 6 cm and no cap) on the lower electrode (lower dielectric). The nano-powders spread uniformly on the petri dish so that most of that were exposed to plasma radiation. Before each plasma deposition, the chamber is pumped down by a two-stage rotary vacuum pump to a pressure of 10–4 mbar, and then it is filled by the N2 and/or CF4 gas to 0.15 bar pressure to ensure high gas purity for the glow discharge. After filling the chamber with the gas, the gas flow was switched off and then the plasma ignited for the treatment process. To generate a uniform N2 (or CF4) plasma, voltage and frequency have been adjusted to 14 kV and 22 kHz. Here, the discharge power was 150 W. The plasma treatment duration was adjusted to 20 min.

Degradation of acid blue 113 (AB113) dye

The effectiveness of ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites in catalyzing the degradation of AB113 dye under UV irradiation was examined. AB113 dye (C32H21N5Na2O6S2, weight: 681.65 g/mol, λmax: 566 nm) is an acid dye containing a diazo group and is commonly utilized by textile manufacturers. This water-soluble azo dye produces a blue colloidal solution. The degradation of AB113 in the ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 composites was investigated under different conditions, such as different pH levels (3.0–8.0) obtained, through the addition of HCl or NaOH and reaction time intervals (5–25 min). A 200 mL of dye solution was put into a flask, followed by the addition of 40 mg of the catalyst (this optimum amount was obtained based on the preliminary studies). After being exposed to irradiation for a specific duration, the photocatalyst particles were separated through centrifugation. The elimination of dye was assessed by means of a spectrophotometer at the wavelength of maximum absorbance, which was 566 nm. The catalytic efficiency in the decomposition of AB113 was determined through Eqs. (1),

where Ao and At denote the AB113 concentrations at time 0 and t (s), respectively, with t being the duration of irradiation.

Catalyst characterization

The FESEM was utilized to analyze the surface morphology, dimensions, and shapes of the nanocomposites at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV (TESCAN MIRA3-XMU). Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) mapping characterized the elemental distribution of the fabricated samples. Moreover, X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were generated to analyze the phase and crystal structure of the specimens. The scans were conducted in the 2θ range from 10◦ to 80◦ using an X-ray diffractometer (Philips PW 1830 diffractometer) with Cu- Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). To investigate the influence of N2 and/or CF4-plasma treatment on the as-prepared ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite, Raman Spectra have been recorded at room temperature using a spectrometer (Bruker-Senterra) which had a laser wavelength of 532 nm. The molecular vibrations of the samples were investigated using infrared spectra recorded with the support of KBr pellets in the wavelength range of 400–4000 cm−1 with an FTIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer 100). Moreover, by applying a BELSORP-mini II instrument, N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms at 77 K were obtained. The specific surface area of the nanocomposites was determined using the BET method. Porosity parameters were obtained through the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method. The UV-Vis reflectance spectra were measured employing a UV-2100 Shimadzu spectrophotometer. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) was done to measure the optical properties of light-absorbing nanoparticles in the UV–visible region.

Results and discussion

A schematic representation of the plasma treatment of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite powder using a low-pressure DBD reactor is illustrated in Fig. 1. Herein, the photocatalytic tests were performed for untreated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite, N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, respectively.

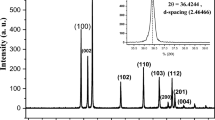

The XRD patterns for the ZnS and TiO2 nanoparticles, untreated ZnS/TiO2, and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 are given in Fig. 2(a). The spectrum of plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2nanocomposites shows weak and broad peaks around 30° and 48° corresponding to the (111) and the (220) of the ZnS phase, respectively49,52. The characteristic peaks representing N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites were observed at 2θ = 25.5°, 37.8°, 48.1°, 53.9°, 54.1°, 62.8° corresponding to the (101), (004), (200), (211), (204), (116) and (215) crystal planes of the anatase TiO2, respectively53. From the XRD patterns, it can be concluded that all the nanocomposites show high crystallinity suggesting that the structure remains unchanged upon N2 and CF4plasma treatments. The Debye-Scherrer equation, D = Kλ/βCosθ, is used to calculate the crystalline size of the nanoparticles, where D is the nanoparticles crystalline size, K represents the Scherrer constant (0.98), λ denotes the wavelength (1.54), and β denotes the full width at half maximum (FWHM)52,53. Hence, the average crystalline size calculated using the Debye-Scherrer equation for the untreated ZnS/TiO2 is about 41.12 nm, and for the N2 and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 are about 42.85 and 44.68 nm, respectively. The result showed an increase in the crystalline size by applying plasma, which was further investigated using FESEM analysis.

The FTIR spectra of the produced ZnS and TiO2 nanoparticles, ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite, and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 can be observed in Fig. 2(b). The peaks appeared at 508 and 617 cm−1in the FTIR spectrum of ZnS are related to the Zn-S vibration54, and the broad peak observed at 750 –500 cm−1 in the spectrum of the TiO2is associated with the stretching vibrations of the Ti-O in anatase titania55. These peaks can also be seen in the FTIR spectra of both the untreated and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites. In the FTIR spectra of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites, the peak observed at 1100 cm−1 is the characteristic vibration peak of the ZnS. As can be seen, the intensity of this peak decreased in the spectrum of the CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2nanocomposite which may be related to plasma chemical etching of the catalyst surface56. This effect can lead to morphological changes on the catalyst surface, which was confirmed by subsequent characterization. The bands at 1635 –1615 cm−1 and the broad peaks about 3500 –3000 cm−1 correspond to the physisorbed water molecule that appears on the FTIR spectra of the untreated and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2nanocomposites52. It can be observed that the intensity of this peak declined in the spectrum of the CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, an effect than can be due to the cleavage of hydrogen bonds and adsorbed water evaporation55.

Figure 2(c) shows the Raman spectra of the prepared nanocatalysts. The peaks at 146, 194, 399, 514, and 640 cm−1 corresponded to the Eg, Eg, B1g, A1g, and Eg modes of anatase TiO2 and ZnS/TiO2, respectively57. According to the results, no significant change was observed in terms of band position for plasma-treated nanocomposites. However, the peak intensity decreased in the case of plasma-treated nanocomposites. Plasma treatment leads to the emergence of defects in the crystal structure of ZnS/TiO2by creating oxygen vacancies, which may lead to improved photocatalytic activity58. This defect reduces the peak intensity in the Raman spectra of the plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites.

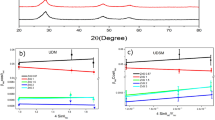

The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and BJH plots of the prepared photocatalysts have been given in Fig. 3(a) and (b), respectively. The untreated ZnS/TiO2 and N2-plasma-treated composite shows an type -IV curve, and the CF4-plasma-treated composite shows a type -V curve, with H3-type hysteresis loop in their isotherms. This indicates that the structure of all nanocomposites is mesoporous. However, there is a change in the adsorption behavior of the CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, which may be due to changes in the morphology of the catalyst. The V-type isotherm usually indicates the weak adsorbate-adsorbate interactions. The BET surface area of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite was about 128 m2 g−1, which was higher than that of the plasma-treated ones. The specific surface area of the N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite is about 73 m2 g−1. Besides, the specific surface area of CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite is about 15 m2 g−1. Compared with untreated ZnS/TiO2, the specific surface area of plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 decreased because the surface pores were filled by the plasma species generated by N2 and/or CF4electrical discharges59. Figure 3(b) shows the BJH plots, which present additional information about the pore distribution. The average pore size of the prepared nanocomposites was 10.8, 33.9, and 51.9 for ZnS /TiO2, N2-plasma-treated and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, respectively. The reasons for the increases in the pore sizes in plasma treated ZnS/TiO2is the hitting by high energy of charged particles generated by plasma60. The ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite showed a pore volume of 0.072 cm3 g–1, while the pore volume of N2-plasma and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 were 0.053 and 0.039 cm3 g−1respectively. In the field of photocatalysis, nanostructured pores can act as pathways for charge carriers to penetrate the interior, thereby reducing the recombination rates and improving the catalytic performance61. Therefore, the N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite would offer more sites accessible for the adsorption of the organic dye than CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2.

The UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) absorption spectrum of the untreated ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites was recorded within the range of 200–700 nm, as shown in Fig. 4(a). It was observed that the nanocomposites have a wide UV absorption band in the range from 200 to 390 nm. The optical absorption edge was obtained from spectra by the intercept on the wavelength axis for a tangent drawn on absorption spectra.The band gap energy (Eg) of the untreated and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites can be calculated by the equation, αhv = A (hv-Eg)n/2, where α is the absorbance, h is Planck’s constant, v is the light frequency, A is a constant, Eg is the band gap energy and the value of n depends on the type of optical transition32. In this regard, we presented the Tauc plot (obtained from the UV-Vis DRS) in Fig. 4(b) showing the band gap energy of the untreated ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites. For untreated ZnS/TiO2, the optical band gap energy has been 3.65. While, the band gap energy of the N2-plasma-treated and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 was found to be 3.48 and 3.26 eV, respectively. This decrease in band gap energy can boost the photocatalytic performance of the plasma-treated nanocatalysts. The reduction in band gap after plasma treatment may be due to the production of defects in the crystal structure of ZnS/TiO2by creating oxygen vacancies62, as it has been confirmed by the Raman spectroscopy results. The anion and cation vacancies in the crystal structure created by plasma treatment, can attract photogenerated electrons, increase surface charge transfer, and diminish the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic performance63.

The FESEM images of untreated ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated nanocomposites are presented in Fig. 5. As can be seen in this image, the untreated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite contained relatively uniform particles with spherical shape and a size distribution of 31.2–80.0 nm (average size of 41.4 nm). However, after treatment with N2 and CF4 plasmas, it can be seen that the size of the nanoparticles increases. The size distribution of the plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 was found to be 31.2–250.0 nm, with an average size of 75.6 and 87.5 nm for N2 and CF4-plasma-treated composites. This increase in the particle size can be attributed to the increase in surface energy of the nanoparticles due to the collision of energetic ions by the plasma. In fact, the system tends to reduce energy by decreasing the surface to-volume ratio (as it was observed in the BET surface area results) through increasing the size of the nanoparticles64. It can also be seen that by plasma treatment, the surface of the catalyst was etched, an effect that is more intense in the case of CF4-plasma treatment. Etching introduces structural vacancies in the crystal structure and enhances charge carrier separation and light absorption, that improves the photocatalytic performance of the plasma-treated nanocomposites65.

To check the produced samples’ chemical composition of the produced samples, EDS analysis was done (see Fig. 6). The EDS results confirm the presence of Zn, Ti, S, and O elements in a hybrid nanocomposite structure. The lack of other elements in the analysis implies the extreme purity of the prepared nanocomposites. No notable changes were observed in the composition of the catalysts after plasma treatment, and the surface of the catalysts has been found to be a uniform mixture of both TiO2 and ZnS. The slight decrease in Ti and O content observed in N2 and CF4 plasma-treated nanocomposites could be due to their vacancies in the structure of plasma-treated photocatalysts.

The photocatalytic performance of untreated ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites have been assessed by measuring the decomposition of AB113 dye solution as a model reaction under UV light irradiation at pH 7 (see Fig. 7). After 25 min of UV irradiation, the AB113 is almost degraded completely in the presence of N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite (about 95%). In contrast, it is degraded by 64% and 46% in the presence of CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 and untreated ZnS/TiO2, respectively. Although the specific surface area of ZnS/TiO2 is higher than that of plasma-treated nanocomposites, the photocatalytic performance of N2-plasma-treated nanocatalyst is almost two times higher than untreated one. This is because of the creation of defects and vacancies in the crystal structure of the plasma-treated catalysts, which leads to a narrower bandgap and more noticeable light-absorbing ability in the UV light region. Moreover, the free electrons generated in plasma medium can enhance photocatalytic activity of the prepared nanocomposite by participating in reduction reactions, preventing electron-hole recombination, and increasing charge carrier density. The findings show that although the optical band gap energy of the CF4-plasma-treated catalyst is lower than the N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, its photocatalytic activity is lower. As mentioned earlier, N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite offers more accessible sites for organic dye adsorption than CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2.

Figure 8 shows the influence of different pH levels on the decomposition of AB113 in the presence of ZnS/TiO2, N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2nanocomposites. As can be seen in this figure, the highest dye removal happened at pH 7. When the pH is low, the production of hydroxyl radicals decreases because of the low concentration of OH64. Above the optimal pH value (pH = 7), the AB113 degradation decreased as a result of the repulsion between the negatively charged surface of the catalyst and hydroxide ions. Moreover, at elevated pH levels, the oxidizing radicals are scavanged and are not able to degrade the AB113 molecules66,67. It can be concluded that the increased photocatalytic efficiency of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites treated with plasma can be ascribed to the synergistic effect of some factors, which are described as follows. The plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites possess accessible pores, which provide abundant active sites for photocatalytic degradation of product reaction and assist mass exchange between AB113 molecules and photocatalytic degradation products across the ZnS/TiO2 surface. Besides, the excited atoms in plasma can change the physicochemical properties of the treated composition. The formation of various radicals in plasma-treated samples plays a significant role in the decomposition of AB113 on the ZnS/TiO2surface under UV-light exposure. Oxygen vacancies present on the surface of plasma-treated nanocomposites can serve as traps for electrons and holes67. These properties can raise the separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, thereby promoting efficient UV-light photocatalytic activity for AB113 degradation.

The schematic illustration of the photocatalytic performance of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite is drawn in Fig. 9. While the UV light is irradiated, it generates the photons needed to create electron-hole pairs. The results showed that the band gap energy of N2 and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 was 3.48 eV and 3.26 eV, respectively, which were lower than the untreated ZnS/TiO2 (3.65 eV). In the case of the N2 plasma, there are some molecular bands in plasma medium including the N2 first positive system (B3Πg) emission and N2 second positive system (C3Πu) produced by many excitations and quenching processes, the N+ 2 negative system (B2∑+u), and the atomic nitrogen generated by electron impact dissociation (N2+ e → 2 N + e)68,69,70. Besides, in the case of the CF4 plasma, CF4 molecules are dissociated into F, CF, CF2, and CF3radicals71,72,73. These radicals, especially free fluorine, are highly efficient for dry etching processes [ 73, 74]. The free fluorine can remarkably roughen the catalyst surface and generate distortions around the adsorption sites leading to production of cation and anion vacancies74,75,76. These vacancies produced during the plasma treatment can cause the band gap of the plasma-treated photocatalyst to be narrowed. In this regard, an electron from the conduction band (CB) of ZnS moved to the CB of TiO2, whereas, the hole transmission occurs from the valance band (VB) of TiO2 to the VB of ZnS. This band structure assists dissociation of the electron-hole pairs, so that electrons diminish molecular oxygen to generate superoxide radical anions (.O2−), meanwhile, holes oxidize H2O to make hydroxyl radicals (.OH). Therefore, subsequently AB113 molecules are oxidized by these active species.

Conclusions

In summary, the photocatalytic performance of untreated ZnS/TiO2 and plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite particles has been investigated in the presence of nitrogen and tetrafluoromethane plasma. The ZnS/TiO2 hybrid photocatalysts were fabricated through the hydrothermal method and modified by N2 and CF4 plasma using a low-pressure DBD reactor. The characteristics of the plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites have been analyzed by FTIR, XRD, Raman, FESEM, EDS, BET, BJH, and DRS analyses. The prepared nanocomposites were employed for the mineralization of AB113 in the presence of UV light. The plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites showed a higher photocatalytic efficiency than untreated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite. It was perceived that the N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite would offer more sites accessible for the adsorption of the organic dye than CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2. After 25 min of UV irradiation, the AB113 is almost completely degraded in the presence of N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite (about 95%). In contrast, it was degraded by 64% and 46% in the presence of CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 and untreated ZnS/TiO2, respectively. The photocatalytic performance of N2-plasma-treated nanocatalysts is nearly two times higher than that of untreated ZnS/Ti O2. This is due to the creation of defects and vacancies in the crystal structure of the plasma-treated catalysts, which leads to a narrower bandgap and superior light-absorbing ability in the UV light region. The impact of various pH values on the photocatalytic degradation of AB113 was investigated in the presence of ZnS/TiO2, N2-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2, and CF4-plasma-treated ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposites. It was found that the highest dye removal happened at pH 7. This study showed an eco-friendly efficient approach to increase the photocatalytic performance of nanocomposites to degrade organic pollutants.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Low, J., Yu, J., Jaroniec, M. & Wageh, S. Al-Ghamdi, Heterojunction photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 29(20), 1601694 (2017).

Garg, A. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of Bisphenol-A using N, Co Codoped TiO2 Catalyst under Solar Light. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 765 (2019).

Chang, T. et al. A critical review on plasma-catalytic removal of VOCs: Catalyst development, process parameters and synergetic reaction mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 828, 154290 (2022).

Khodamorady, M. & Bahrami, K. A novel ZnS-CdS nanocomposite as a visible active photocatalyst for degradation of synthetic and real wastewaters. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 2177 (2023).

Ma, R. et al. Enhanced visible-light-Induced Photoactivity of Type-II CeO2/g-C3N4 nanosheet toward Organic pollutants Degradation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7 (10), 9699–9708 (2019).

Ansari, S. A., Khan, M. M., Ansari, M. O. & Cho, M. H. Nitrogen-doped titanium dioxide (N-doped TiO2) for visible light photocatalysis. New J. Chem. 40 (4), 3000–3009 (2016).

Qutub, N., Singh, P., Sabir, S., Sagadevan, S. & Oh, W. C. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of Acid Blue dye using CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 5759 (2022).

Zhu, M. et al. New Method to synthesize S-Doped TiO2 with stable and highly efficient photocatalytic performance under indoor sunlight irradiation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 3 (12), 3123–3129 (2015).

Gusain, R., Kumar, N., Opoku, F., Govender, P. P. & Ray, S. S. MoS2 Nanosheet/ZnS composites for the visible-light-assisted photocatalytic degradation of Oxytetracycline. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4 (5), 4721–4734 (2021).

Han, G., Kim, J. Y., Kim, K. J., Lee, H. & Kim, Y. M. Controlling surface oxygen vacancies in Fe-doped TiO2 anatase nanoparticles for superior photocatalytic activities. Appl. Surf. Sci. 507, 144916 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Carbon Quantum Dot/TiO2 nanohybrids: efficient photocatalysts for hydrogen generation via intimate contact and efficient charge separation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2 (2), 1027–1032 (2019).

Ghamarpoor, R., Fallah, A. & Jamshidi, M. A review of synthesis methods, modifications, and mechanisms of ZnO/TiO2-Based photocatalysts for photodegradation of contaminants. ACS Omega. 9, 24 (2022).

Liu, S., Zhang, N., Tang, Z. R. & Xu, Y. J. Synthesis of one-Dimensional CdS@TiO2 Core-Shell nanocomposites Photocatalyst for Selective Redox: the dual role of TiO2 Shell. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 4, 11 (2012).

Balayeva, N. O., Fleisch, M. & Bahnemann, D. W. Surface-grafted WO3/TiO2 photocatalysts: enhanced visible-light activity towards indoor air purification. Catal. Today. 313, 63–71 (2018).

Kanakaraju, D. & Chandrasekaran, A. Recent advances in TiO2/ZnS-based binary and ternary photocatalysts for the degradation of organic pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 868, 161525 (2023).

Harish, S. et al. ZnS quantum dots impregnated-mesoporous TiO2 nanospheres for enhanced visible light induced photocatalytic application. RSC Adv. 7, 26446–26457 (2017). Y. Hayakawa.

Fu, Y. et al. Synthesis of ternaryZnO/ZnS/MoS2 piezoelectric nanoarrays for enhanced photocatalytic performance by conversion of dual heterojunctions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 556, 149695 (2021).

Hsieh, P. Y. et al. TiO2 nanowires-supported sulfides Hybrid photocatalysts for durable solar hydrogen production. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 3006–3015 (2019).

Pan, C. et al. CuO/TiO2 nanobelt with Oxygen vacancies for visible-light-driven photocatalytic bacterial inactivation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5 (8), 10980–10990 (2022).

Porcu, S., Secci, F. & Ricci, P. C. Advances in hybrid composites for photocatalytic applications: a review. Molecules. 27, 6828 (2022).

Franco, A. et al. Photocatalytic decolorization of methylene blue in the presence of TiO2/ZnS nanocomposites. J. Hazard. Mater. 161, 545–550 (2009).

Liu, D., Liang, H., Xu, T., Bai, J. & Li, C. Construction of ternary hollow TiO2-ZnS@ZnO heterostructure with enhanced visible-light photoactivity. J. Mol. Struct. 1248, 131493 (2022).

Heris, S. Z., Etemadi, M., Mousavi, S. B., Pourfard, M. M. & Ramavandi, B. Preparation and characterizations of TiO2/ZnO nanohybrid and its application in photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater. J. Photochem. Photobiol Chem 443, 114893 (2023).

Hussain, M. Z., Yang, Z., Huang, Z., Jia, Q. & Zhu, Y. Recent advances in Metal-Organic frameworks Derived nanocomposites for Photocatalytic Applications in Energy and Environment. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100625 (2021).

Zhang, X. & Jiang, S. P. Layered g-C3N4/TiO2 nanocomposites for efficient photocatalytic water splitting and CO2 reduction: a review. Materialstoday Energy. 23, 100904 (2022).

Neyts, E. C., Ostrikov, K., Sunkara, M. K. & Bogaerts, A. Plasma catalysis: Synergistic effects at the Nanoscale. Chem. Rev. 115, 13408–13446 (2015).

Carreon, M. L. Plasma catalytic ammonia synthesis: state of the art and future directions. J. Phys. D. 52, 483001 (2019).

Vanraes, P. et al. Removal of atrazine in water by combination of activated carbon and dielectric barrier discharge. J. Hazard. Mater. 299, 647–655 (2015).

Khosravi, S., Jafari, S., Zamani, H. & Nilkar, M. Inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli Biofilms by Air-Based Atmospheric-pressure DBD plasma. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 193, 3641–3650 (2021).

Martines, E., Cavazzana, R., Cordaro, L. & Zuin, M. The helical resonator: a Scheme for radio frequency plasma generation. Appl. Sci. 11, 7444 (2021).

Dey, S. et al. Review of Polymeric nanocomposites for Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7 (5), 4588–4614 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Reniers, N-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst Coatings synthesized by a Cold Atmospheric plasma. Langmuir. 35 (22), 7161–7168 (2019).

Dezhpour, A., Ghafouri, H., Jafari, S. & Nilkar, M. Effects of cold atmospheric-pressure plasma in combination with doxorubicin drug against breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 209, 202–210 (2023).

Shabani, H., Dezhpour, A., Jafari, S., Moghaddam, M. M. & Nilkar, M. Antimicrobial activity of cold atmospheric-pressure argon plasma combined with chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) extract against P. Aeruginosa and E. Coli biofilms. Sci. Rep. 13, 9441 (2023).

Martines, E. et al. Wound healing improvement in large animals using an indirect Helium plasma treatment. Clin. Plasma Med. 17-18, 100095 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. Effects of dielectric barrier discharge plasma on the catalytic activity of Pt/CeO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B. 238, 328–338 (2018).

Blanquet, E., Nahil, M. A. & Williams, P. T. Enhanced hydrogen-rich gas production from waste biomass using pyrolysis with non-thermal plasma-catalysis. Catal. Today. 337, 216–224 (2019).

Abdel-Wahed, M. S., Hefny, M. M., Abd-Elmaksoud, S., El-Liethy, M. A. & Kamel, M. A. Removal of chemical and microbial water pollutants by cold plasma combined with Ag/TiO2-rGO nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 9850 (2022).

Nilkar, M. et al. Enhanced electrochemical performance of CNx/Co3O4 multilayer electrodes prepared by a hybrid non-thermal plasma/sol-gel method for energy storage applications. J. Alloys Compd. 966, 171476 (2023).

Pelaez, M. et al. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 125, 331–349 (2012).

Chuang, S. I., Yang, H., Chen, H. W. & Duh, J. G. Modification of TiO2 powder via atmospheric dielectric barrier discharge treatment for high performance lithium-ion battery anodes. Thin Solid Films. 596, 250 (2015).

Acharya, T. R. et al. Evaluation of degradation efficacy and toxicity mitigation for 4-nitrophenol using argon and air-mixed argon plasma jets. Chemosphere. 358, 142211 (2024).

Lin, A. et al. Nanosecond-pulsed DBD plasma-generated reactive oxygen species trigger immunogenic cell death in A549 lung carcinoma cells through intracellular oxidative stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (5), 966 (2017).

Fronzi, M., Iwaszuk, A., Lucid, A. & Nolan, M. Metal oxide nanocluster-modified TiO2 as solar activated photocatalyst materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 074006 (2016).

Brun, P. et al. Martines, Helium Generated Cold plasma finely regulates activation of Human Fibroblast-Like Primary cells. Plos One. 8, 104397 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. Promotion of Epoxy Resin Surface Electrical Insulation Performance and its Stability by Atmospheric Fluorocarbon Dielectric Barrier Discharge. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 27, 1973–1981 (2020).

Ruan, H. O. et al. Sh. Zhu, Filler fluorination of nanoTiO2/ER composites and their surface insulation properties: a comparison of dielectric barrier discharge and chemical solution fluorination. J. Phys. D Appl Phys. 53, 145204 (2020).

Khosravi, S., Jafari, S., Zamani, H. & Nilkar, M. Synergistic antimicrobial effects of atmospheric pressure non-thermal argon plasma and ciprofloxacin antibiotic against multi-drug resistant P. Aeruginosa biofilm. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 213301 (2022).

Talebi, S., Chaibakhsh, N. & Shoeili, Z. M. Application of nanoscale ZnS/TiO2 composite for optimized photocatalytic decolorization of a textile dye. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 15, 378–385 (2017).

Nilkar, M., Ghodsi, F., Jafari, S., Thiry, D. & Snyders, R. Effects of nitrogen incorporation on N-doped DLC thin film electrodes fabricated by dielectric barrier discharge plasma: structural evolution and electrochemical performances. J. Alloys Compd. 853, 157298 (2021).

Latifi, A., Nilkar, M. & Jafari, S. Plasma-assisted surface modification of MXene/carbon nanofiber electrodes for electrochemical energy storage. J. Energy Storage. 100, 113740 (2024).

Bagheri, F. & Chaibakhsh, N. Efficient visible-light photocatalytic ozonation for dye degradation using Fe2O3/MoS2 nanocomposite. Sep. Sci. Technol. 56 (17), 3022–3032 (2021).

Shirke, B. S., Korake, P. V., Hankare, P. P., Bamane, S. R. & Garadkar, K. M. Synthesis and characterization of pure anatase TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 22, 821–824 (2011).

Jothibas, M. et al. Structural and optical properties of zinc sulphide nanoparticles synthesized via solid state reaction method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 28, 1889–1894 (2017).

Wang, X. Q. et al. Spectral characteristics of cotton seeds treated by a dielectric barrier discharge plasma. Sci. Rep. 7, 5601 (2017).

Choi, K. R., Woo, J. C., Joo, Y. H., Chun, Y. S. & Kim, C. L. Dry etching properties of TiO2 thin films in O2/CF4/Ar plasma. Vacuum 92, 85–89 (2013).

Sekar, R., Sivasamy, R., Ricardo, B. & Manidurai, P. Ultrasonically synthesized TiO2/ZnS nanocomposites to improve the efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 132, 105917 (2021).

Naz, M. Y. et al. Optical characterization of non-thermal plasma jet energy carriers for effective catalytic processing of industrial wastewaters. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 2896 (2021).

Panomsuwan, G., Saito, N. & Ishizaki, T. Simple one-step synthesis of fluorine-doped carbon nanoparticles as potential alternative metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3 (18), 9972–9981 (2015).

Yu, F. et al. Enhanced solar photothermal catalysis over solution plasma activated TiO2. Adv. Sci. 7 (16), 2000204 (2020).

Abdulrahman, A. F., Barzinjy, A. A., Hamad, S. M. & Almessiere, M. A. Impact of radio frequency plasma power on the structure, Crystallinity, dislocation density, and the Energy Band Gap of ZnO Nanostructure. ACS Omega. 6, 31605–31614 (2021).

Jubeer, E. M., Manthrammel, M. A., Subha, P. A., Shkir, M. & Biju, K. P. A.AlFaify, defect engineering for enhanced optical and photocatalytic properties of ZnS nanoparticles synthesized by hydrothermal method. Sci. Rep. 13, 16820 (2023).

An, H. R. et al. Advanced Nanoporous TiO2 photocatalysts by hydrogen plasma for efficient solar-light photocatalytic application. Sci. Rep. 6, 29683 (2016).

Asghari, S., Mohammadi, M. A., Julaei, R. & Taheri, R. A. Surface modification of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide nanoparticles by Argon Plasma for medical applications. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 9, 563–568 (2022).

Busharat, M. A. et al. Effect of Nonthermal plasma on cation distribution and photocatalytic activity of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles for Dye Degradation Application. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 14, 8059559 (2024).

Mishra, S. R., Panigrahi, B., Gadore, V., Sarkar, N. & Ahmaruzzaman, M. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of CuS/O, N-CNT composite for solar-driven organic contaminant degradation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 18022 (2024).

Moafi, H. F., Hafezi, M., Khorram, S. & Zanjanchi, M. A. The effects of non-thermal plasma on the morphology of Ce-doped ZnO: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of hierarchical nanostructures. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 37, 159–176 (2017).

Coitout, H. & Cernogora, G. Experimental study of the temporal evolution of N2(C3Πu) and N2(B3Πg) in a nitrogen pulsed discharge. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 39, 1821 (2006).

Müller, A., Pozebon, D. & Dressler, V. L. Advances of nitrogen microwave plasma for optical emission spectrometry and applications in elemental analysis: a review. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 35 (10), 2113–2131 (2020).

Uhm, H. S., Ki, S. H., Baik, K. Y. & Choi, E. H. Influence of oxygen on generation of reactive chemicals from nitrogen plasma jet. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 9318 (2018).

Fanelli, F., Fracassi, F. & d’Agostino, R. Deposition and etching of fluorocarbon thin films in atmospheric pressure DBDs fed with Ar–CF4–H2 and Ar–CF4–O2 mixtures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 204 (11), 1779–1784 (2010).

Zhang, C. et al. Hydrophobic treatment on polymethylmethacrylate surface by nanosecond-pulse DBDs in CF4 at atmospheric pressure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 311, 468–477 (2014).

Pakpum, C. & Boonyawan, D. Redeposition-free of silicon etching by CF4 microwave plasma in a medium vacuum process regime. Surf. Coat. Technol. 397, 126018 (2020).

Lee, R., Lim, C., Lee, H., Kim, S. & Lee, Y. S. Visible light photocatalytic activity of TiO2 with carbon-fluorine heteroatoms simultaneously introduced by CF4 plasma. Korean J. Chem. 39, 3334 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Preparation and Photocatalytic Wettability Conversion of TiO2-Based superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir. 22 (23), 9477–9479 (2006).

Choi, K. R., Woo, J. C., Joo, Y. H., Chun, Y. S. & Kim, C. I. Dry etching properties of TiO2 thin films in O2/CF4/Ar plasma. Vacuum 92, 85 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Guilan Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Khosravi: Methodology, Investigation, Writing–original draft. N. Chaibakhsh and S. Jafari: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. M. Nilkar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khosravi, S., Chaibakhsh, N., Jafari, S. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnS/TiO2 nanocomposite by nitrogen and tetrafluoromethane plasma treatments. Sci Rep 14, 28385 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78009-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78009-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Light-driven photocatalytic TiO2 nanomaterials for environmental pollutant degradation and cancer treatment: emerging strategies and mechanistic perspectives

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)