Abstract

The primary objective of this study was to identify the factors associated with the development of depressive symptoms in elderly breast cancer (BC) patients and to construct a nomogram model for predicting these symptoms. We recruited 409 patients undergoing BC treatment in the breast departments of two tertiary-level hospitals in Jiangsu Province from November 2023 to April 2024 as our study cohort. Participants were categorized into depressed and non-depressed groups based on their clinical outcomes. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to identify independent risk factors for depression among BC patients. Multivariate analysis revealed that monthly income, pain score, family support score, and physical activity score significantly influenced the onset of depression in older BC patients (P < 0.05).The risk prediction model, constructed using these identified factors, demonstrated excellent discriminatory power, as evidenced by an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.824. The maximum Youden index was 0.627, with a sensitivity of 90.60%, specificity of 72.10%, and a diagnostic threshold value of 1.501. The results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ² = 3.181, P = 0.923) indicated that the model fit the data well. The calibration curve for the model closely followed the ideal curve, suggesting a strong fit and high predictive accuracy. Our nomogram model exhibited superior predictive performance, enabling healthcare professionals to identify high-risk patients early and implement preventative measures to mitigate the development of depressive symptoms. This study is a cross-sectional study that lacks longitudinal data and has a small sample size. Future research could involve larger samples, multicenter studies, and prospective designs to build better clinical predictive models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common type of cancer among women, with global cancer research institution data showing that in 20221, there were 20 million new cases of cancer worldwide, including a staggering 2.3 million new cases of female BC, making it the second common cancer type globally. In the same year, BC ranked fourth in terms of mortality rates, with a death rate of 6.9%2. From the analysis of the age distribution among BC patients, individuals aged 60 years or older comprised 31.3% of the total BC patient population in China. It is projected that this percentage will escalate to 41.4% by 20303. BC presents with a range of symptoms across various age groups. People of different age groups tend to experience accompanying symptoms after being diagnosed with BC. Compared to young women, elderly BC patients are more likely to develop negative emotions such as anxiety and depression due to multiple comorbidities, functional limitations, and the presence of larger tumors and greater lymph node involvement4,5. These factors severely impact the quality of life for these patients. Studies have demonstrated that the detection rate of depressive states in elderly BC patients stands at 31.3%4. Furthermore, studies by Desai et al. show that the incidence of BC accompanied by a depressed state in women over 80 years old is slightly lower than in women under 806. However, the mortality rate is relatively higher, which could be attributed to a lack of mammography screening, higher cancer stage at the time of diagnosis, inadequate treatment, and the presence of multiple comorbidities6. Depressive symptoms accompanying BC not only diminish the immunity of BC patients, leading to tumor recurrence, metastasis, and deterioration7,8, but they also elevate the 5-year mortality rate9. This exacerbation of health outcomes negatively impacts the treatment and rehabilitation process. Studies have shown that screening for depressive symptoms in BC patients can reduce the relative risk of mortality by 15-20%10. Therefore, establishing an early warning and screening mechanism for depressive symptoms in BC patients is crucial.

Currently, researchers employ scale assessments for the early screening of depressive symptoms in elderly BC patients4,5,11,12. However, these assessments are not ideal as a primary screening method due to their time-consuming nature and potential for inaccurate interpretation.

With the advent of the era of information technology and big data, clinical risk prediction modeling has become a new tool for early identification and warning of diseases13. Nomogram-based clinical risk prediction models incorporate multiple risk factors as variables, integrating and visually presenting their scores through graphics. These models assist healthcare providers in analyzing the probability of outcomes related to risk factors based on score results, playing a pivotal role in patient health education and the implementation of anticipatory nursing interventions13. This approach has been widely adopted in clinical research areas such as esophageal cancer14,15, stroke16,17, colorectal cancer15,18, but has yet to be applied in the context of early screening for depressive symptoms in elderly BC patients. This study primarily aims to investigate the risk factors for depression in elderly BC patients, establish a nomogram model, and provide a basis for early identification and prevention of depressive symptoms in this patient cohort.

Methods

Participants

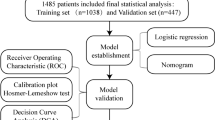

This study selected 409 elderly BC patients who received treatment in the breast internal medicine departments of two Grade III Class A hospitals in Jiangsu Province between November 2023 and April 2024 as subjects (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) BC diagnosis conforming to the standards outlined in the Chinese Guidelines for BC Screening and Early Diagnosis19 and confirmed by physical examination, imaging, biopsy, or other methods; (2) age ≥ 60 years; (3) mentally competent with no communication barriers; (4) aware of their condition and willing to cooperate with the researchers. The exclusion criteria included: (1) having a history of severe heart, brain, lung, or other organic functional disorders, or a history of depression; (2) concurrent with other cancers besides BC; (3) participation in other studies during the period of this investigation. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangsu Provincial Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine (Ethical Review Number: 2023-LWKYZ-075). Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their families.

Data collection

In this study, a self-administered questionnaire was employed to gather data on patients’ demographics (gender, age, occupation, marital status, education, and economic status), clinical characteristics (tumor grade, size, and metastasis), lifestyle factors (smoking and alcohol consumption history), and familial history of cancer.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess the degree of depression, the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to evaluate pain, the Perceived Social Support from Family Scale (PSS-Fa) was used to measure family support, and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess exercise levels. Specifically, the IPAQ was utilized to evaluate the level of physical activity in the patients.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software and the rms package in R 3.6.3. In our dataset, apart from PHQ-9, PSS-Fa, and IPAQ scores, which have no missing data, approximately 5% of the other variables contain missing values. Specifically, the extent of missingness varies across different variables, ranging from less than 1% to around 10%. The variable with the highest rate of missing data is tumor grading, with a missing rate of approximately 10%. Considering the relative percentage of missing data and the potential mechanism of missing at random (MAR), we opted for multiple imputation (MI) as our preferred method for handling missing values, as it offers several advantages over traditional methods such as listwise deletion or mean imputation. Multiple imputation not only helps to preserve the inherent variability in the data but also provides valid standard errors and unbiased parameter estimates under the MAR assumption. By generating multiple plausible values for each missing datum, MI accounts for the uncertainty inherent in the imputation process, thereby offering more accurate statistical inference. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD), with independent sample t-tests for comparisons between two groups and ANOVA for multiple group comparisons. Skewed continuous data were presented as median (interquartile range, M[IQR]), and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for two-group comparisons. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages (%), and chi-square tests were employed for comparisons between two or more groups. Variables with statistical significance in univariate analysis were included in logistic regression analysis. The predictive capability of the model was assessed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. A nomogram was constructed based on the multivariable model, with calibration plots utilized for internal validation of the model. This study employed two-tailed tests, considering P < 0.05 statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

In this study, we analyzed data from a total of 409 elderly BC patients, whose mean age ranged from 60 to 75 years [64(61,67)]. Of these, 212 patients developed depressive symptoms, equating to an incidence rate of 51.83% (212/409).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors

Univariate analysis results indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in age, marital status, place of residence, surgical procedure, disease type, smoking history, family history, distant metastasis, treatment modality, and menopausal status between the depressed and non-depressed groups (P > 0.05).Conversely, statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the depressed and non-depressed groups regarding body mass index (BMI), health insurance type, occupation, history of alcohol consumption, lymph node metastasis, education level, tumor grading, monthly income, pain score, physical activity score, and family support score. Detailed information is presented in Table 1. After performing multivariate logistic regression analysis, the following variables showed statistical significance: Monthly income of patients、Pain score、Family support score、Physical activity score, as shown in Table 2.

Application of the depression prediction model

Statistically significant variables from the logistic regression analysis were employed as predictors to construct a nomogram prediction model using the rms package in R 3.6.3 software, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In practical clinical application, by integrating patient data, a vertical line is drawn from the score points of each indicator towards the “Total Score” standardized rating axis. The cumulative scores from all indicators are then added up at the corresponding point on the total score axis, and another vertical line is drawn downwards along the “Risk Probability” axis, with the resulting score representing the probable likelihood of depressive symptoms occurring in elderly BC patients. The area under the ROC curve for this model is 0.824 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.781 to 0.866], with a sensitivity of 90.60%, specificity of 72.10%, a maximum Youden Index of 0.627, and a diagnostic odds ratio of 1.501, indicating a high discriminatory capacity of the model. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness-of-fit yields X2 = 3.181, P = 0.923, suggesting a satisfactory fit of the regression model. Further details are provided in Fig. 3. The prediction model was validated using the bootstrap method, and the results showed that the model prediction accuracy was 0.868, indicating that it has excellent prediction capability. A calibration curve was created using R software to further evaluate the model’s validity, which indicates that the model’s calibration curve fits well with the standard ideal curve, as elaborated in Fig. 4.

Discussion

The results of this study showed a 51.83% (212/409)incidence rate of depressive symptoms in elderly BC patients, this may be due to limited abilities to ask for help and to communicate with others or worries related to treatment costs and family financial difficulties20. Elderly people have to cope with general functional impairments and the loss of loved ones, and have often a poorer network of social support than younger patients21. Constructing a risk prediction model allows for rapid identification of patients at risk of developing depressive symptoms before they manifest. This enables targeted and prioritized preventive measures. The nomogram risk prediction model developed in this study is characterized by simplicity, speed, and excellent predictive performance, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.824. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test result with P > 0.05 suggests that the model possesses good discriminative ability and clinical efficacy in identifying depression symptom risks, fulfilling the objective of preliminary screening for high-risk populations. Moreover, the four predictors in the nomogram model are easily accessible, and healthcare providers can readily assign values to each predictor and calculate a total score. Applying the optimal cut-off value of 1.501 to differentiate high- and low-risk groups not only reduces the computational burden for users but also saves assessment time.

In our study, we found that pain is a risk factor influencing the likelihood of depressive symptoms in BC patients, consistent with findings from studies by Kyranou and Zhuo Xuepiao22,23, among others. Most middle-aged and elderly BC patients in long-term treatment will face different levels of pain, patients with advanced cancer will be pain24, it also often cause middle-aged and elderly BC patients appear insomnia, anxiety, fear, the deterioration of the treatment effect of cancer, secondary damage to patients. In addition to the pain of breast loss, elderly people with BC also need to bear the physical pain of cancer treatment. The pain resulting from BC. The symptoms of BC are very hidden, most patients will not produce strong pain in the early stage of BC, with the deterioration of the condition, there will be patients with skin itching, ulceration, desquamation and other symptoms, accompanied by faint burning feeling. The pain resulting from the operation. Especially after breast eradication, due to the possibility of nerve damage, patients will have a strong sense of burning and needle prick after surgery, even daily dressing, arm lifting, and other movements will be accompanied by serious discomfort. Pain from chemotherapy. Due to the different conditions of patients, the dosage of chemotherapy drugs is also different, so the symptoms of pain are different. Gastrointestinal adverse reactions will be more, including nausea, vomiting, stomach distension, serious cases will appear adverse reactions of anorexia. Pain from radiotherapy. Radiotherapy process generally does not produce severe pain, according to the radiotherapy site has different effects, the general performance is physical fatigue, skin redness and swelling.

The univariate and multivariate regression analysis in this study further showed that monthly income and financial income significantly predicted the occurrence of depressive symptoms, and the lower the monthly income, the higher the incidence of depressive symptoms. This is generally consistent with the findings of the previous studies20.A qualitative study has demonstrated that, despite the gradually improving survival rates of elderly BC patients due to rapid advancements in modern technology, the substantial costs incurred from subsequent surgeries, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and other treatments impose a heavy financial burden on patients, rendering economic stress a significant risk factor for depression in this population25. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare professionals promptly identify such high-risk individuals and periodically provide psychological counseling to alleviate their mental distress.

Family is central to ameliorating patients’ negative emotions. This study found that patients with inadequate family support had a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms compared to those with high levels of family support, which is consistent with the studies23,26,27.Compared with young cancer patients, elderly cancer patients have the characteristics of poor tolerance, more comorbidities, and decreased body function28,29. 66% of elderly patients want relevant information about “side effects caused by tumor treatment”; 65% of elderly patients need emotional guidance30 of “tumor recurrence problem”. Due to unmet patient information and psychological needs, concerns about adverse reactions, and comorbidities, greatly reduce the quality of life of elderly cancer patients31,32. Supportive care can not only reduce the psychological and spiritual needs of BC patients, but also help patients with emotional relief and reduced symptoms33,34,35.

Physical activity is closely related to the development of depressive symptoms in elderly BC patients, serving as one of the predictive factors for depression in this target patient group.Studies confirmed that regular physical activity can reduce the incidence of depression36, that physically inactive older people have a higher risk of depression37, and that physical activity can be an effective alternative to depression medication38. The anti-inflammatory effect of physical activity on our human body can effectively prevent or improve the clinical manifestations of depression39.As reported by the current researchers, physical inactivity is a modifiable risk factor for depression, and increased physical activity can be an important potential target for the prevention of depressive episodes40, and physical activity is significant for the prevention of depression in older adults. To our knowledge, many people with depressive symptoms have turned to non-pharmacological interventions such as physical exercise and physical activity must be long term to maintain adequate preventive depression benefits41.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the data used in this study were obtained from only two tertiary hospitals in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, resulting in a small sample size and limited generalizability. Second, the model has been only internally validated, and further external validation is necessary to confirm its validity and applicability. Third, this study lacks longitudinal data, which limits our understanding of the temporal dynamics and developmental trends of the phenomena under investigation.

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal that lower monthly income (<3000 RMB), presence of pain, low levels of family support, and inadequate physical activity are risk factors for depressive symptoms in middle-aged and young BC patients. The nomogram model, established based on these factors, demonstrates good predictive performance, providing a basis for the early identification and prevention of depressive symptoms in this patient population.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Liu, Z. C. et al. Interpretation on the report of Global Cancer statistics 2020. J. Multidiscipl. Canc. Manag. (Electronic Version). 7, 1–14 (2021).

Shao, Y. L. et al. Breast cancer incidence and mortality in women in China: Temporal trends and projections to 2030. Cancer Biology Med. 18, (2021).

Jones, S. M. W. et al. Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the women’s Health Initiative. J. Cancer Surviv. 9, 620–629 (2015).

Ms, P. et al. Depressive symptoms and associated health-related variables in older adult breast cancer survivors and non-cancer controls. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 48, (2021).

Desai, P. & Aggarwal, A. Breast cancer in women over 65 years- a review of screening and treatment options. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 37, 611–623 (2021).

David, D. et al. Dermal carotenoid measurement is inversely related to anxiety in patients with breast cancer. J. Investig. Med. 66, 1–5 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Mol. Psychiatry. 25, 3186–3197 (2020).

Bach, L., Kalder, M. & Kostev, K. Depression and sleep disorders are associated with early mortality in women with breast cancer in the United Kingdom. J. Psychiatr. Res. 143, 481–484 (2021).

Varghese, F. & Wong, J. Breast Cancer in the Elderly. Surg. Clin. North Am. 98, 819–833 (2018).

Efrossini, D., George, P., Fotios, T. A., Michalis, V. & G, A. & Physical activity and sociodemographic variables related to global health, quality of life, and psychological factors in breast cancer survivors. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manage. 11, 371–381 (2018).

Williams, G. R. et al. Frailty and health-related quality of life in older women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 27, 2693–2698 (2019).

Gu, H. Q., Zhou, Z. R., Zhang, Z. H. & Zhou, Q. Clinical prediction models: basic concepts, application scenarios, and research strategies. Chin. J. Evidence-Based Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1454–1456 (2018).

Zhi, Y. C. et al. Focus on patients with early esophageal cancer-a prognostic nomogram. Translational cancer Res. 9, 7469–7478 (2020).

Zi, F. Y. et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for colorectal cancer patients with synchronous peritoneal metastasis. Front. Oncol. 11, 615321 (2021).

Shu, L. C., Chun, Y. M., Ce, Z. & Rui, S. Nomogram to predict risk for early ischemic stroke by non-invasive method. Medicine. 99, e22413 (2020).

Qi, Y. et al. Development and internal validation of a multivariable prediction model for 6-year risk of stroke: a cohort study in middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. BMJ open. 11, e048734 (2021).

Wu, J., Li, L., Zhang, B. H., Wu, S. Y. & Song, Q. B. Risk genes and nomogram model for lymph node metastasis of colon cancer. Cancer Res. Prev. Treat. 47, 947–952 (2020).

The Society of Breast Cancer,China Anti-Cancer Association. Screening and early diagnosis of breast cancer in China: A practice guideline. China Oncol. 32, 363–372. https://doi.org/10.19401/j.cnki.1007-3639.2022.04.010 (2022).

Hong, J. S. & Tian, J. Prevalence of anxiety and depression and their risk factors in Chinese cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 22, 453–459 (2014).

Evaluation of depression. In patients undergoing chemotherapy. Health Sci. J. 2, (2008).

Kyranou, M. et al. Differences in depression, anxiety, and quality of life between women with and without breast pain prior to breast cancer surgery. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 17, 190–195 (2013).

Wu, X., Liu, J. N., Peng, X. Y., Li, X. M. & Mao, J. J. Risk factors of postoperative depression in patients with breast cancer and establishment of clinical predictive model. J. Hebei Med. Univ. 42, 900–903 (2021).

Lu Meiling, L. & Zhiqin Progress in the hospice care needs of patients with end-stage cancer. Nurs. Res. 36 (05), 850–857 (2022).

Liu, L. J. & Sun, F. J. A qualitative study on the causes of anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients under 45 years old during chemotherapy. Mod. Med. J. 42, 413–414 (2014).

Erika, M., Kristy, M., Laura, A. S. & Kelly, B. G. Scott A, L. Family support: A possible buffer against disruptive events for individuals with and without remitted depression. J. Fam. Psychol. 32, 926–935 (2018).

Jessie, J., Nickolas, W., Christine, D. N., Adrienne, T., Ruth, C. & J, H. & Depression and family arguments: disentangling reciprocal effects for women and men. Fam. Pract. 37, 49–55 (2020).

DeSantis, C. E. et al. Cancer statistics for adults aged 85 years and older, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 452–467 (2019).

Corbett, T. & Bridges, J. Multimorbidity in older adults living with and beyond cancer. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat. Care. 13, 220–224 (2019).

Yang Y. A cross-sectional questionnaire survey of the needs and satisfaction of elderly cancer survivors in China. The Chinese Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Proceedings of the 2016 Comprehensive Academic Symposium. Beijing: Chinese Society of Gerontology and Gerontology, 2016:356–368.

Ornstein, K. A. et al. Cancer in the context of aging: Health characteristics, function and caregiving needs prior to a new cancer diagnosis in a national sample of older adults. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 11, 75–81 (2020).

Scotté, F. et al. Addressing the quality of life needs of older patients with cancer: A SIOG consensus paper and practical guide. Ann. Oncol. 29, 1718–1726 (2018).

Momino, K. et al. Collaborative care intervention for the perceived care needs of women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy after surgery: A feasibility study. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 47, 213–220 (2017).

Lozano-Lozano, M. et al. Integral strategy to supportive care in breast cancer survivors through occupational therapy and a m-health system: design of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 16, 150 (2016).

Liao, M. N. et al. Education and psychological support meet the supportive care needs of Taiwanese women three months after surgery for newly diagnosed breast cancer: A non-randomised quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 51, 390–399 (2014).

Ströhle, A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J. Neural Transm. 116, 777–784 (2009).

Teychenne, M., Ball, K. & Salmon, J. Physical activity and likelihood of depression in adults: A review. Prev. Med. 46, 397–411 (2008).

López-Torres Hidalgo, J. & DEP-EXERCISE Group. Effectiveness of physical exercise in the treatment of depression in older adults as an alternative to antidepressant drugs in primary care. BMC Psychiatry. 19, 21 (2019).

Eyre, H. A., Papps, E. & Baune, B. T. Treating depression and depression-like behavior with physical activity: An immune perspective. Front. Psychiatry. 4, 3 (2013).

Schuch, F. B. et al. Are lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness associated with incident depression? A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Prev. Med. 93, 159–165 (2016).

Saeed, S. A., Cunningham, K. & Bloch, R. M. Depression and anxiety disorders: Benefits of Exercise, yoga, and Meditation. Am. Fam Phys. 99, 620–627 (2019).

Funding

The study was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Cadre Healthcare Scientific Research Grant Project (No. BJ23019), the Jiangsu Provincial Association of Maternal and Child Healthcare Scientific Research Grant Project (No. FYX202350), the Special Fund for the Project of Enhancing Academic Capability of Integrative Nursing (No. ZXYJHHL-K-2023-M20), and the Jiangsu Provincial Graduate Student Practice and Innovation Program Project (No.SJCX24_0833).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We certify that all authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the appropriateness of the study design and method, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data and the manuscript drafting and revision. Y.M.: manuscript drafting, the design conceived this study; Y.M., B.W. and J.L.: conception of the work; R.X. and L.G.: data acquisition; Y.M. and A.X.: data analysis and interpretation; B.W. and J.L.: Subject Guidance, critical revision, the design conceived this study. Given Li Jia-ning’s substantial contribution to this study, all authors agreed during a meeting to recognize her equally with the first author. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mao, Y., Li, J., Shi, R. et al. Construction of a nomogram risk prediction model for depressive symptoms in elderly breast cancer patients. Sci Rep 14, 26433 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78038-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78038-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Risk prediction models for depression in older adults with cancer

BMC Psychiatry (2025)