Abstract

The sustainable use of industrial byproducts in civil engineering is a global priority, especially in reducing the environmental impact of waste materials. Among these, coal ash from thermal power plants poses a significant challenge due to its high production volume and potential for environmental pollution. This study explores the use of controlled low-strength material (CLSM), a flowable fill made from coal ash, cement, aggregates, water, and admixtures, as a solution for large-scale coal ash utilization. CLSM is suitable for both structural and geotechnical applications, balancing waste management with resource conservation. This research focuses on two key CLSM properties: flowability and unconfined compressive strength (UCS) at 28 days. Traditional testing methods are resource-intensive, and empirical models often fail to accurately predict UCS due to complex nonlinear relationships among variables. To address these limitations, four machine learning models—minimax probability machine regression (MPMR), multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), the group method of data handling (GMDH), and functional networks (FN) were employed to predict UCS. The MARS model performed best, achieving R2 values of 0.9642 in training and 0.9439 in testing, with the lowest comprehensive measure (COM) value of 1.296. Sensitivity analysis revealed that cement content was the most significant factor with obtaining R = 0.88, followed by water (R = 0.82), flowability (R = 0.79), pond ash (R = 0.78), curing period (R = 0.73), and fine content (R = 0.68), with fly ash (R = 0.55) having the least impact. These machine learning models provide superior accuracy compared to traditional methods, particularly in handling complex interactions between mix components. The proposed models offer a practical approach for predicting CLSM performance, supporting sustainable construction practices and the efficient use of industrial byproducts. The novelty of this study lies in the development of precise design equations for evaluating UCS, promoting both practical applicability and environmental sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The utilization of industrial byproducts in civil engineering has become a globally adopted strategy to promote environmental sustainability. Among these byproducts, the vast quantities of coal ash generated by thermal power plants to meet societal energy demands have resulted in the deposition of millions of tons near these plants, posing significant environmental risks. If not properly managed, coal ash can contaminate natural resources. To address this, various methods for the sustainable use of coal ash have been proposed, with a major focus on its use as a partial cement replacement in concrete, as an admixture in soil stabilization, and in brick production1,2,3,4,5. According to the studies by Bhatt et al.6, only 50% of the produced coal ashes are used effectively for different applications in India.

Controlled low-strength material (CLSM) or flowable fills constitute a viable solution for the utilization of coal ashes in large quantities. CLSM involves a mixture of coal ash, cement, fine aggregates, coarse aggregates, cement, water, and admixtures and has applications in both structural and geotechnical engineering fields7,8. As alternatives to coal ash, many other industrial waste products are used for CLSM production. The production of CLSM using different industrial byproducts and the utilization of CLSM for various applications have been discussed in detail by various researchers9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

The two main properties that must be considered in the production and utilization of CLSM mixes are their flowability and unconfined compressive strength (UCS) at 28 days. As per7, the flowability value of CLSM mixes must lie in the range of 200–300 mm for the mix to be flowable in nature without much bleeding and difficulties in pumping the mix through the pumps. The UCS of the flowable fill mixes depends on the application of CLSM. For low-strength CLSM mixes, the UCS at 28 days should be less than 0.7 MPa. In applications such as structural fills, the UCS values of the mix should be in the range of 8.3 MPa23,24,25,26,27,28,29. The UCS of CLSM mixes depends on various factors, such as the constituent materials present in the mix, the percentage of each material used in the production of CLSM mixes, the curing period, and the flowability of the mix.

The mechanical and physical characteristics of CLSM are currently assessed through two primary methods. The most common involves extensive physical and mechanical testing of numerous samples with varying ages, mix proportions, and material combinations. Although widely used, this approach is resource-intensive, requiring significant computational effort, time, and financial investment. Another approach employs empirical regression models, typically constructed using statistical software to develop multivariate, nonlinear, and polynomial regression models based on experimental data and empirical assumptions. While regression models are popular in CLSM analysis, they rely on certain statistical assumptions, and even when these assumptions are met, the models may not always provide accurate predictions. Furthermore, empirical regression methods often struggle to predict the UCS of CLSM mixes due to the complex nonlinear relationships among variables and the limited generalizability of these models. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) to predict the UCS of CLSM mixes remains underexplored. These findings highlight the need for innovative approaches to enhance UCS prediction in CLSM mixes.

Concrete and cement-based materials use a mix proportion procedure similar to that of CLSM mixes. The prediction of their physical and mechanical properties is accomplished by utilizing a wide range of approaches. Among the several predictive strategies that are included in these methodologies are multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), minimax probability machine regression (MPMR)30, the functional network (FN), the group method of data handling (GMDH)31 and others32,33,34. It has become clear that MARS is one of the most successful methods for making predictions of concrete mixes and other geotechnical properties. Compared with other methods, MARS, GMDH, MPMR, and FN yield better performance in terms of both speed and accuracy in terms of predicting the physical and mechanical properties of materials. In the realm of engineering, these machine learning (ML) models have considerable advantages and acquired recognition due to their effectiveness in handling complicated problem-solving scenarios, especially in predicting the physical and mechanical properties of concrete and CLSM mixes35,36,37,38,39. Khan et al.40 proposed the MEP-based model to predict the UCS of kaolin and BC soils mixed with fly ash (FA). Khan et al.41 introduced advanced artificial intelligence models such as GBT, ANFIS, and GEP to predict the CS of ground-granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and fly ash (FA) concrete mixtures. Onyelowe et al.42 proposed gene expression programming (GEP) to effectively predict the California bearing ratio (CBR), unconfined compressive strength (UCS), and R value of expansive soil treated with hydrated lime-activated rice husk ash. Usama et al.43 proposed a robust multiexpression programming (MEP) model for predicting the optimal unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of expansive soils (ES) stabilized with waste glass powder (WGP) and fly ash (FA), offering a cost-effective and time-efficient alternative to traditional experimental methods while promoting sustainability in geoenvironmental engineering. Zhao et al.44 proposed several optimization machine learning algorithms for support vector regression (SVR), namely, the PSO-SVR, GA-SVR, and GS-SVR models, to predict the flowability and UCS of CLSM made from waste soil, with GA-SVR showing superior predictive accuracy, with performance metrics of R2 = 0.948, RMSE = 8.826 and MAE = 7.608 for the flowability testing set and R2 = 0.934, RMSE = 0.178 and MAE = 0.115 for the UCS testing set. SHAP analysis revealed water and CA as the most influential variables for flowability and UCS predictions, respectively. Shin et al.45 proposed a genetic algorithm-based model to predict the UCS of CLSM mixes for recycling water sludge from interior stone production materials as fine aggregates. In their study, they proposed an empirical equation for UCS prediction based on a genetic algorithm model whose accuracy with experimental and model-predicted UCS values was R2 = 0.864. In recent years, MARS GMDH, MPMR, genetic programming (GP), and FN have gained more popularity in assessing various geotechnical properties46,47,48,49. However, the adoption of MARS, GMDH, MPMR, and FN for predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes with varying percentages of pond ash, fly ash, cement, and water present in the mix has yet to be reported in the literature.

This paper examines the significance of various factors influencing the UCS of coal ash-based flowable fills. The key variables considered in this study include the proportions of pond ash, fly ash, cement, and water in the mix, as well as the flowability values at different curing periods (7, 14, 28, 56, and 90 days). The proposed model uses the cement content, fines content in ash, pond ash, fly ash, water, flowability, and curing age as input variables, and the UCS of the CLSM mixes is specified as an output variable. The dataset was carefully curated to enable accurate prediction and analysis of the material’s performance, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of its behavior over time.

Research significance

To mitigate the harmful effects of carbon emissions and minimize the disposal of industrial byproducts, researchers have increasingly focused on repurposing these materials for various applications. Reutilizing industrial byproducts not only reduces the demand for landfill space but also conserves natural resources. The incorporation of materials such as fly ash, kiln dust, pond ash, and quarry dust in flowable fill production offers a sustainable solution to the large-scale disposal of these wastes. Utilizing these byproducts in CLSM mixes enhances the flowability and UCS, making them suitable for a range of applications, including backfill for retaining walls, utility trenches, abandoned mines, and pavement bases. Accurately determining the UCS of CLSM is crucial for identifying appropriate applications. Soft computing techniques offer an efficient means of identifying the key parameters influencing UCS and provide a robust tool for interpreting results. This research aims to develop reliable and effective machine learning models to predict the UCS of CLSM mixes at various curing stages. The study makes a significant contribution to geotechnical engineering by providing precise design equations for UCS evaluation, with a strong focus on the practical application of the proposed models for geotechnical professionals.

Experimental program

Materials considered for the study

In the present study, flowable fills mixes were produced with different quantities of pond ash, fly ash and cement. In some of the mixtures, only pond ash was considered along with cement, whereas some other samples were prepared by adding pond ash and fly ash in equal proportions. Both fly ash and pond ash used in the present study were obtained from the Ennore Thermal Power Plant, Tamil Nadu, India, as shown in the map in Fig. 1. Figure 1 was generated using QGIS (version 3.34.9-Prizren), an open-source geographic information system, to map the geographical location of the Ennore Thermal Power Plant, Tamil Nadu, India.

Figure 2 shows the key experimental materials used in this study, namely, pond ash, fly ash, and cement. The images provide a visual overview of the physical characteristics of each material. In the context of this research, these materials are integral to understanding the composition and mechanical behavior of CLSM mixes. The visual representations of the materials assist in recognizing physical differences, such as particle size and texture, which may influence the mix design and its performance, particularly in terms of unconfined compressive strength (UCS). Figure 2 supports the material selection and experimental methodology section by providing a clearer understanding of the raw materials used in the mixes.

The grain size distribution curves obtained for both the pond ashes (PA1 and PA2) and the fly ash (FA) considered for the study are given in Fig. 3. The chemical compositions of all the ashes are given in Table 1. The grain size distributions of all the ashes were determined according to the IS 2720 standard specifications and are listed in Table 2. Notably, PA1 contains only 6% fine-grained particles, whereas PA2 contains 57% fine-grained particles. The percentage of fines in FA is much greater than that in both pond ashes (84%). The classification of these samples as per IS 1498 (1970) is also given in the table. Comparatively, the specific gravity of FA is 2.11, which is lower than the specific gravity of pond ash, which ranges from 2.16 to 2.22. Pond ash has a relatively large range of specific gravity values. The pH values of all the ashes are slightly greater than 7, indicating alkaline behavior for all the ashes. An OPC of grade 53 was used as the binder in the flowable fill mixes. Figure 4 shows SEM images of both the pond ashes and the fly ash considered for the study. The SEM images clearly predict the spherical shape of the cenospheres present in the fly ash and pond ash, which are in unreacted forms.

Mix proportion

Twenty-four samples were taken into consideration for the current study, and the cement content, pond ash content, water content, and fly ash concentration of the mixture were altered to obtain the desired results. The flowability and UCS of the mixture after 28 days were used to determine the percentage of cement and water that should be included in the mixture. The technique of trial and error was utilized to ascertain the quantity of water that was necessary to achieve both flowability levels. For the PA1 ash, the samples were prepared by varying the cement content in the mix by 1 to 4% of the weight of the pond ash considered in the mix. For pond ash PA1, only 2 to 3% cement content was required to achieve a UCS value of less than 0.7 MPa at 28 days. The samples were not prepared with the addition of 1% cement to the PA1 ash, as the CLSM mix was not harden after 24 h. For the pond ash PA2, the fines content present in the ash was greater than that in PA1, which meant that a greater quantity of cement, specifically 4%, was required to reach the UCS after 28 days. This resulted in the cement concentration of the mixture ranging from 1 to 5% percent of the total weight of the pond ash considered. The same percentage of cement was required for the mix prepared by replacing 50% of the pond ash (PA1) with FA. As PA1 contains only a lower percentage of fines, part of PA1 was replaced by a finer FA to assess the effect of fine content on the UCS and flowability of the CLSM mix (represented as PA-FA). Thus, the twenty-four mixes were prepared by varying the cement content from 1 to 5% of the ash considered in the mix to attain a UCS of less than 0.7 MPa at 28 days and by varying the water content to achieve a flowability of both 200 and 300 mm.

Mixing procedure for flowability

The CLSM mix proportion was determined via a Hobart Mixer by first dry mixing the constituent materials in the mix such as pond ash and cement for the PA1-and PA2-based mixes and then mixing PA1, FA and cement in the required quantities for approximately 2 min. Following this, the amount of water that was required to achieve flowability values of 200 and 300 mm was calculated via trial and error. The water was subsequently added into the dry mix, and the mixing process was extended for an additional three minutes. Upon completion of the mixing, the resulting mixture attained a flowable state, rendering it suitable for the preparation of samples for various testing procedures.

Procedure of testing

The prepared mix collected from the Hobart mixer was first used to determine the flowability of the mix. ASTM D6103-04 (2004)50 specifications were followed for testing the samples for their flowability values. The wet mix from the Hobart mixer is filled into a plastic cylinder with a length‒diameter ratio of 2 and a diameter of 75 mm. The cylinder was lifted, and the mix was spread on the glass plate on which the cylinder was kept. The spread diameter is measured in two perpendicular directions and represents the flowability of the mix. The flow cylinder for measuring flowability and the sample used for UCS testing are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 6 shows the CLSM results obtained for 300 mm flowability for PA1-based ash. The figure shows that the mix is highly flowable in nature, and this flowability of the mix is the prime reason for the permeability characteristics of the CLSM mix.

As shown in Fig. 7, the water contents necessary to achieve flowability values of 200 mm and 300 mm for each of the samples are expressed in terms of the ratio of the water cement content to the cement content. A greater quantity of water was needed to attain the specified flowability values for all of the CLSM mixes when the cement concentration was increased. The amount of particles present in the ash is another factor that influences the ratio of water to cement. As the amount of fines that were contained in the ash increased, a significantly greater quantity of water was required to attain the desired flowability. With respect to the CLSM mixes, the ratio of water to cement can range anywhere from 10 to 47, depending on the particle content and flowability, both of which are considered in this study. The values of the water-to-cement ratios were found to be much greater than those of the concrete mixes because of the greater amount of water required to achieve flowability and the lower quantity of cement required to achieve low strength at 28 days for the CLSM mixes.

Following the completion of the tests described in the preceding paragraph, the samples for dry density and UCS testing were prepared for the corresponding water content and cement content. This was done after the water content that was required for the flowability criteria was received from the tests. After the mixtures were made in accordance with the technique that was followed for flowability values of 200 and 300 mm, they were poured into molds with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 120 mm. To determine the dry unit weight values of the CLSM mixes, the wet unit weight of the mix was initially derived by combining the weight of the mix that was filled into the mold with the volume of the mold. The dry unit weight of the mix was then calculated according to the initial water content present in the mix. The dry unit weight values that were produced for all of the mixtures that correlated with flowability values of 200 mm and 300 mm are presented in Fig. 8. It can be observed that the dry unit weight increases with higher cement content in the mixes, a trend consistent across both flowability levels. This is because there is a greater quantity of cement present in the mixture, which contributes to the process of hardening, which ultimately results in a larger unit weight. On the other hand, the dry unit weight of the mix was dependent on the fines content present in the ash. The dry unit weight values of the PA2 ash, which is composed of 57% fines, were much lower than those of the PA1- and PA-FA-based CLSM mixes of the same composition. The reason for this reduction is the presence of fewer coarser-grained particles in the pond ash than in the PA1 ash.

Once the wet unit weight of the mixes is determined, the molds are covered with cling films on two sides to avoid any loss of water and are kept for hardening for UCS testing. After 24 h, the samples were trimmed to a height of 100 mm and stored in desiccators after being covered with cling films for different curing periods. For some of the samples, at lower cement contents, the flowable fill samples did not harden after the samples hardened for 24 h. These samples were not considered for UCS testing. Thus, on the basis of these conditions, the minimum cement content required for CLSM mix production was determined.

For PA1, the sample prepared with a 1% cement content did not harden after 24 h of curing for both 200 mm and 300 mm flowability. A minimum of 2% cement was required to ensure that the samples hardened after 24 h. To gain an understanding of the short-term and long-term strength growth of the mixes, testing was performed on the samples at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 90 days. To achieve a compressive strength of less than 0.7 MPa in a period of 28 days, the amount of cement in the mixture was adjusted from 2 to 4% through a series of experiments. The same procedure was repeated for the 300 mm flow mix.

For the testing of the UCS of the CLSM mixes, the procedure followed ASTM specifications51. A deformation rate of 0.5 mm/min was chosen for loading the samples. A load cell and an LVDT were used for measuring the load and deformation, respectively. Three samples were prepared for each percentage of cement, and the average of three values was reported as the UCS value of that sample for the specified curing time. The same procedure was adopted for all the samples to obtain the UCS values at different curing periods. For all of the samples, the typical stress‒strain curves that were obtained for the UCS test after 28 days of curing are displayed in Fig. 9. These curves were obtained with a cement concentration of 4% and flowability values of 200 and 300 mm. On the basis of the data presented in Fig. 9, the failure pattern clearly exhibits a brittle nature, with failure stresses falling within the range of 0.9% to 1.8%. A further observation that can be made is that the strain at failure tends to decrease as the fines content in the ash decreases, resulting in significantly more brittle behavior than before. The type of ash, the flowability of the mixture, and the amount of cement component that is present in the mix all play a role in determining the eventual stress and failure strain.

The variations in UCS that were obtained at 7 and 28 days for both the 200 mm and 300 mm flowability values are depicted in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively. These variations pertain to the cement content and water-to-cement ratios. Both of these figures show that the UCS values are dependent on the concentration of cement as well as the amount of water present in the mixture. Increasing the cement content led to an increase in the UCS, whereas increasing the W/C ratio led to a decrease in the UCS.

The variation in the UCS with increasing curing period for all the CLSM mixes is shown in Fig. 12a–c. The improvement in the strength with increasing curing period can be clearly noted from the figures. The rate of increase is greater during the initial 28 days of curing. A further increase in the curing period was found to have less impact on the UCS.

Table 3 shows the UCS values obtained for all the samples considered in the present study. The 20 sample data points for both the pond ashes (PA1 and PA2) and the fly ash (FA) CLSM mixes are provided in Table 3.

Details of machine learning models

MARS model

The MARS model is a nonparametric regression and data mining technique that can capture complex relationships between input variables and output variables via a series of piecewise linear or cubic functions. It was developed by Friedman in the early 1990s as an extension of the simpler univariate adaptive regression splines method52. Within each subspace, the MARS algorithm fits a spline function, referred to as the basis function, which partitions the input parameter space into distinct subspaces (BFs) to represent the relationship between each input and output variable. These basis functions are adaptively added, modified, or deleted during the model-building process to best fit the data. Knots serve as the endpoints of each segment, delineating the boundary between one data region and another. Unlike traditional parametric linear regression methods, MARS offers greater flexibility in exploring nonlinear relationships between input and response variables. MARS automatically performs variable selection by choosing the most relevant input variables and their interactions to include in the model, leading to more interpretable and efficient models. Additionally, MARS systematically explores all interaction degrees to uncover potential relationships between variables. By considering all interactions and functional forms among input variables, this method effectively uncovers hidden relationships within high-dimensional datasets, capturing the intricate structures present in the data points. The mathematical Eq. (1) represents the most basic form of the MARS model.

where \(\tilde{y}\left( x \right)\) represents the desired output; \(\beta_{0}\) and \(\beta_{n}\) represent the constant terms used to obtain the best data fit for the particular problem; \(\delta_{n} \left( x \right)\) represents the spline basic function (BF), which can be defined via Eq. (2); and n represents the total number of generated BFs.

where the term \(S_{{\left( {k,m} \right)}}\) is defined as the region of the step function (chosen as either + 1 or -1),\(X_{{v\left( {k,m} \right)}}\) is defined as the label of the output feature, \(T_{{\left( {k,m} \right)}}\) is defined as the location of the knots, and \({\text{k}}_{{\left\{ {\text{m}} \right\}}}\) denotes the total number of knots generated during the simulation. MARS constructs basis functions (BFs) through a comprehensive step-by-step process that spans the entire search domain. An adaptive regression method is employed to ascertain the placement of knots. A two-stage forward and backward procedure is adopted to craft an optimal MARS model. Initially, MARS tends to overfit the data during the forward stage because of the examination of numerous BFs. To mitigate overfitting, redundant BFs are pruned from the model during the backward phase. Generalized cross-validation (GCV) criteria are employed by MARS to identify and eliminate unproductive BFs. The mathematical expression used to express the GCV is presented in Eq. (3).

where N denotes the number of datasets used to develop the model. The term C(B) is defined as the complexity penalty, which is calculated via Eq. (4) as follows:

where B is the total number of BFs, and the term d represents a constant factor of complexity penalty.

Functional network (FN) algorithm

The functional network (FN) algorithm is a machine learning technique that extends the classical artificial neural network (ANN) framework. The FN algorithm was proposed by Castillo et al.53 to increase the interpretability and flexibility of the learning model by incorporating domain-specific knowledge directly into the network structure. Initially, functional networks (FNs) possess a complex topology, which can be simplified into a more straightforward terminology. By integrating domain knowledge with data insights, to solve the “black box” difficulty that neural networks face, FNs are utilized. This allows for the topology of the problem to be inferred. FNs make use of data to estimate the functions of unknown neurons, and they leverage domain knowledge to define the topology of the network. It is assumed that the neural functions of FNs have several arguments and are vector-valued. This contrasts with the sigmoidal function that is utilized in artificial neural networks (ANNs). In contrast to artificial neural networks (ANNs), which make use of predetermined neural functions, parametric and structural learning are utilized to learn and estimate these functions. Compared with artificial neural networks (ANNs), the intermediary layers of FNs make it possible to connect several neuron outputs to the same unit.

Structured and parametric learning functional networks are the two main categories. Parametric learning uses parameterized functional families to estimate neuron functions from data, whereas structural learning relies on topologies and functional equations set by the designer. Data storage, processors, and directed link sets make up a functional network. Equation 5 is suggested as a way to approximate the neural function.

In functional networks, X denotes the input vector, and \(\phi_{ij}\) represents the shape functions, which can be polynomial (e.g., \(1, x, x^{2} , x^{3} , \ldots ,x^{n} )\), trigonometric \(\left( {e.g., \sin \left( x \right),\cos \left( x \right),\tan \left( x \right) \ldots \ldots \sin \left( {2x} \right)} \right)\), or exponential \(\left( {e.g., e^{x} , e^{2x} , \ldots , e^{nx} } \right)\). Associative optimization functions yield algebraic equations. The use of a functional network requires familiarity with the underlying functional equation. Cauchy’s equation is prevalent among functional equations. The effectiveness of the functional network hinges on factors such as the function’s degree/order and the type of fundamental function employed, whether exponential, polynomial, trigonometric (e.g., sine, cosine), or tangent significantly influences its performance and adaptability to diverse problem domains.

Group method of data handling (GMDH)

The group method of data handling (GMDH) model is an algorithm proposed by Ivakhenko54 for locating a linearly parameterized complex polynomial function. Sorting, or the successive evaluation of models chosen from a set of candidate models on the basis of a predetermined criterion, is the process by which this method operates. In almost all cases, GMDH algorithms employ polynomial support functions55. A fundamental relationship between the input and output variables can be represented by a functional Volterra series, the discrete equivalent of which is the Kolmogorov‒Gor polynomial (denoted by Eq. 6). In this equation,\(X\left( {x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots x_{M} } \right)\) is the feature vector, whereas \(A\left( {a_{1} ,a_{2} , \ldots a_{M} } \right)\) denotes the vector of summand coefficients.

The estimation of the model structure’s complexity is derived from the quantity of polynomial terms implemented. The sorting process involves calculating the criterion in response to the gradual modification of the model’s structure. GMDH, as an iterative approach, approaches the optimal regression method but distinguishes itself through the implementation of internal and external sorting criteria and the efficient organization of the search for the optimal model structure. Self-training algorithms of multilayered pattern recognition systems, such as perceptrons or neural networks, resemble the GMDH algorithms in structure. One significant distinction is that polynomial GMDH algorithms handle continuous variables. The identification of the minimum value of the external criterion, which ascertains the optimal configuration of nonphysical models, is feasible solely with continuous variables. Starting with carefully choosing and combining variables in the first layers, it builds polynomial models layer by layer. Iteratively, each layer assesses and improves upon these models with the goal of achieving better performance. In this iterative procedure, variables are fine-tuned at each stage, with the focus being on the most important aspects and the elimination of those that are less important. Finding the top-performing models and variables that have the greatest impact on the final result is the last step of the GMDH process.

Minimax probability machine regression (MPMR)

Within the framework of the minimax probability machine, which is an appealing discriminative classifier that is dependent on prior intelligence, Strohmann and Grudic56 developed the concept. It is possible that the problems that arise during the creation of the regression model are caused by the expansion of the least likelihood of future predictions within a few selected areas of the appropriate valid regression function. The minimax probability machine classification (MPMC) method provides strong support for the MPMR philosophy)57. For the next predictions to fall within the border and the genuine regression function, MPMR constructs the nonlinear regression function that bloats the minimal probability56,58,59. MPMR is an advanced and redesigned version of support vector machine that relies on direct discriminant and raised enhancement to obtain the optimal level of prediction.

One important part of this method is that when the predictor variables are evaluated, all the inputs are mixed within the upper border \(( + \delta )\) and the lower boundary (δ). The definition of the region between the borders is the regression surface where the model does not make any distributional assumptions, and both limits of likelihood identify the area for misclassification of the point. The unknown regression algorithm produces the input data \(f:\quad R^{d} \to \quad R\), which is in the form of:\(y = f(x) + \lambda\).

where \(x \in R^{d}\) are generated in accordance with a few constrained distributors Ω; also, the output vector is \(y \in R\), and Var[\(\lambda\)] = \(\sigma^{2}\), where \(\sigma \in R\) is finite. For f, the approximation function is \(\hat{f}\). Similarly, for each x derived from the distribution Ω, the output y may be expressed as and approximated as ŷ.

The model’s evaluated limits are based on the least likelihood (\(\Gamma\)) that \(\hat{f}(x)\) is between the boundaries of δ and y56,57

Since it is possible to acquire direct estimates of Γ, this formula for regression problems is novel. As a result, the ability to forecast the regression function may be quantified via a constraint on the minimal probability that falls inside the real regression function’s δ.

The kernel function of the MPMR model, which is integrated into the minimax probability machine classification, has the following form:

where \(x_{i}\) represents the learned data, \(\alpha_{i}\) and \(\lambda\) represent the output parameters, and \(K_{ij} = \phi (x_{i} ,x_{j} )\) represents a kernel function that must meet the mercer condition.

Descriptive statistics of the datasets

Table 4 presents comprehensive statistical summaries of the experimental dataset used for the development of machine learning models, emphasizing their distribution characteristics. The most common forms of descriptive statistics are mode, median, and mean measurements of central tendency as well as minimum, maximum, and standard deviation measures of variability and skewness and kurtosis of distribution. To assess the symmetry and distribution patterns in relation to a normal distribution, skewness and kurtosis were examined. Kurtosis determines how many tails the dataset has, whereas skewness indicates how asymmetrical the data distribution is. For predictive models to be robust, it is critical that the data distribution aligns with the recommended ranges, specifically, skewness values close to 0 and kurtosis values between -10 and + 10, thereby ensuring reliable statistical analysis. Table 4 provides the details of the variables included in the study with units of measurement and statistical measures. A total of 120 experimental data points were considered in this study to construct the machine learning models. The variables include the cement content, fine content in the ash, pond ash, fly ash, water added, flowability, curing period and unconfined compressive strength (UCS). The cement content varied from 5 g/m to 783 g/m, with a mean of 25.63 g/m and a standard deviation of 12.41 g/m. In this work, pond ash and fly ash are used as cementitious materials with partial replacement of cement. Pond ash varies from 500 g/m to 1000 g/m, with an average value of 812.5 and a standard deviation of 243.08. Fly ash is replaced with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 500 g/m, with a mean value of 187.50 and a standard deviation of 243.08. The volume of water added varied from 400 to 300 ml, with a mean and standard deviation of 462.25 and 41.58, respectively. Flowability is measured in mm, with a minimum value of 200 mm and a maximum value of 300 mm. The curing period varied from 7 to 90 days. UCS testing was conducted at various curing periods, and the unconfined compressive strength varied from 0.01 MPa to 1.40 MPa, with a mean value of 0.45 MPa and a standard deviation of 0.31. To strengthen the model’s resilience, the data points in this study are evenly dispersed across the whole range. An additional piece of evidence for this is that the input variables’ skewness and kurtosis values are within the acceptable range. The frequency distribution histogram in Fig. 13 shows how the input variables are related to the UCS output variable. These representations of the dataset visually demonstrate the data distribution range, demonstrating the uniformity and dispersion of the data points across the whole spectrum.

Data processing and computation of the models

Data preprocessing is a critical step in data analysis and machine learning pipelines. It involves transforming raw data obtained from experiments into a clean and usable format, which is essential for improving the quality of the data and, consequently, the performance of machine learning models. The initial step in data preprocessing involves normalization, which scales numerical features to a uniform range of 0 to 1. The primary objective of normalization is to ensure that features with different scales or units of measurement are treated consistently during model training. Since many machine learning algorithms are sensitive to feature scales, this step is crucial. Scaling restrictions might impede optimization convergence or make solution discovery more difficult if feature ranges are substantially varied. Scaling constraints influence model sensitivity and feature relevance; narrower limits highlight specific qualities, whereas broader limits reduce them. When the scales of characteristics vary, it becomes difficult to compare their relevance or coefficients, complicating the model’s comprehension. First, to preprocess the dataset, feature scaling is performed for all the selected features in the range of [0, 1] via Eq. (7) to minimize the cost function of the proposed models, improve the model interpretability and facilitate the regularization parameters and penalties to the model parameters to prevent overfitting60,61,62,63,64,65.

After feature scaling, data splitting is performed by splitting the whole dataset into two separate phases, namely, training and testing. The correlation plot among the variables is presented in Fig. 14. The correlation observed in Fig. 14 among the input variables and their correlation with the UCS of the CLSM mixes helps in identifying the input variables that are most strongly related to the output variable. Strongly correlated features can be crucial in predicting the output, whereas weakly or noncorrelated features may be less relevant in predicting the UCS. The results indicate that the cement and curing periods are significantly positively correlated with the UCS, with correlation values of 0.54 and 0.24, respectively, whereas the other input variables are poorly correlated with the UCS. Water has a significant positive correlation with cement, fine content, pond ash, and flowability, with correlation values of 0.59, 0.68, 0.52, and 0.57, respectively. However, water is negatively correlated with fly ash, with a correlation value of—0.52.

The dataset was divided into training and testing sets, often using fivefold cross-validation techniques to develop the proposed ML models. This method helps in evaluating the model’s performance and its ability to generalize to new, unseen data by splitting the data into multiple subsets and training/testing the model multiple times. The training set consists of 80% of the total dataset, and the remaining 20% is taken as the testing set. These preprocessing steps ensured that the dataset was ready for effective training of the proposed regression models, leading to more accurate and reliable predictions of the UCSs of the CLSM mixes.

The study employed a fivefold cross-validation technique to assess the accuracy and generalizability of the predictive models provided, thereby mitigating the danger of overfitting. The dataset was partitioned into 5 equal folds, where one-fold was designated as the test set and the remaining four folds were utilized for training. This process is repeated 5 times for all the proposed models, with each iteration using a different fold as the validation set and remaining fourfold as the training of the models, as shown in Fig. 15.

The process was iterated 5 times, which resulted in 5 performance estimations. Fivefold cross-validation is essential for robust performance estimation, as it reduces overfitting, optimizes hyperparameter tuning, maximizes data utilization for training and validation, and offers insights into model variability. After performing fivefold cross validation, the optimum hyperparameters of the proposed models are determined, and the performances of the models corresponding to each fold are determined. Figure 16(a)–(c) show the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) corresponding to each fold. The overall average value of all the parameters corresponding to each optimum model is illustrated in Fig. 16(d). The R2 value for the MARS model in each iteration is greater than those of the other models. Similarly, the error parameters, such as the RMSE and MAE, corresponding to each node for the MARS model are lower than those for the other models. The performance parameters corresponding to the best performing fold average accuracy achieved in each iteration determine the model’s overall performance, as depicted in Fig. 16(d).

Performance evaluation metrics

Performance evaluation metrics are crucial for evaluating the efficiency and dependability of machine learning models, especially with respect to forecasting new data. These measures aid in assessing whether a model is overfitting or effectively generalizing patterns. An analysis is conducted on the most frequently used metrics (presented in Table 5) for regression tasks to compare the UCSs of the CLSM mixes predicted by the models with the actual experimental UCS values36,66. This analysis provides valuable information about the correctness of the models.

where \({\text{R}}_{{\text{e}}}\) is defined as the residual error, which is calculated as the difference between the experimental and predicted UCS values (i.e.,\({\text{R}}_{{\text{e}}} = \, \sim {\text{UCS}}_{{{\text{exp}}}} - \, \sim {\text{UCS}}_{{{\text{predicted}}}} ).{\text{UCS}}_{{{\text{expavg}}}}\) is defined as the average value of the experimental UCS values of the CLSM mixes. SD represent the standard deviation of the predicted UCS value. Where \({\text{m2}}0\) is defined as the number of data points of the ratio of the experimental and predicted UCS values falls within the range of 0.8 to 1.2, \({\text{M}}\) represents the number of data points67.

Results and discussion

Configuration of the developed models

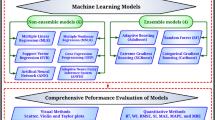

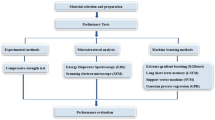

In the context of the constructed regression model within geotechnical engineering, the use of MARS, FN, GMDH and MPMR represents advanced methodologies for predictive modeling. These models necessitate meticulous parametric configurations and extensive simulations via a trial-and-error approach to achieve optimal performance. The all-proposed models under consideration have been developed within the MATLAB 2016a framework, specifically utilizing Simulink for their implementation. During the construction of the FN model, regularization is employed to prevent overfitting by penalizing overly complex models. Hyperparameters such as L1 (lasso) or L2 (ridge) regularization coefficients help control the amount of regularization applied. In the FN model, the basis functions represent the building blocks used to approximate the target function. During the construction process of the FN model, to obtain the best solution, the tan polynomial function was used with a seven-order polynomial. However, during the construction of the GMDH model in MATLAB 2016a, the environment involves configuring several hyperparameters, including the maximum number of layers, regularization parameters, maximum number of neurons per layer, criterion for model selection, and polynomial degree, which influences the model’s performance and ability to generalize to new data. The optimal values of the hyperparameters for GMDH are obtained as the maximum number of layers = 4, the maximum number of neurons per layer = 15, and alpha = 0.6. A higher polynomial degree is utilized in the GMDH model to capture more complex relationships between the input features and UCS of the CLSM mix. The MARS model, in particular, is constructed through the use of piecewise linear basis functions, where the selection of both the type and quantity of basic functions (BFs) is critical to ensuring predictive accuracy. As previously discussed, the inclusion of a penalty term within the model is essential to prevent overfitting by limiting the number of BFs incorporated into the model. After generating an initial set of BFs, the MARS model employs a pruning process, governed by a hyperparameter, to strike a balance between model complexity and accuracy. Proposed models such as MARS, GMDH, FN, and MPMR have considerable predictive capacities for calculating the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of controlled low-strength material (CLSM) combinations. However, the computational costs and difficulties can vary greatly. MARS models use piecewise linear regression to represent nonlinear data interactions. They are adaptable and durable, but iterative fitting and pruning of basis functions, particularly those with numerous interactions and splines, can be computationally expensive for large datasets. GMDH models create polynomial models by selecting and combining variables in a self-organizing manner. The computational cost of large or high-dimensional datasets is determined by the number of iterations and the degree of polynomiality. FN models use fuzzy logic and neural networks to resolve uncertainties and complex patterns; nevertheless, backpropagation and multiple neural network layers make training time-consuming and costly. MPMR, which uses polynomial regression fitting, is easier, but it can become computationally expensive and overfit with higher polynomial degrees and more predictors. However, during fivefold cross-validation, all suggested models must be trained and evaluated on several subsets, which can increase the overall computational load. While these advanced models provide excellent prediction capabilities for the UCS of CLSM combinations, they are computationally expensive and complex. MARS and GMDH can be computationally costly because of their iterative nature and model fitting methods, whereas FN models require significant resources for neural network training, and the complexity of MPMR is determined by polynomial degrees and feature interactions. When selecting a model, these characteristics must be carefully considered to balance forecast accuracy with computational efficiency. The detailed methodology flowchart is presented in Fig. 17.

In this study, the MARS model uses piecewise-cubic basis functions, with an initial total of 11 BFs, including intercepts. During the pruning process, one BF is eliminated, resulting in a final model composed of 10 BFs. Although the selected BFs are inherently piecewise-cubic, they are represented in a piecewise-linear form within the model. A detailed summary of the BFs and their corresponding GCVs, MSEs and R2 GCVs is provided in Table 6. To develop the optimal predictive model, the basic function was systematically varied, and three key statistical metrics, namely, MSE, GCV, and R2, were employed to evaluate the performance of the MARS models. As shown in Fig. 18, a significant reduction in the MSE and GCV values is observed at the 4th basis function, whereas the R2 values increase markedly as the number of basic functions increases from 4 to 15, eventually stabilizing near the final solution. The MSE reaches its minimum, and R2 reaches its maximum when the number of basic functions reaches 15. Thus, the MARS model with 15 basis functions was identified as the optimal model for constructing the correlation functions.

The empirical relationships established between the input variables and the UCS of the CLSM mix, as derived from the MARS model, are encapsulated in Eq. (8).

Statistical details of the results

In evaluating the performance of proposed machine learning models, several statistical metrics are commonly used to provide a comprehensive understanding of their accuracy and reliability. The key metrics include R2, WMAPE, NS, RMSE, VAF, PI, WI, MAE, \({\text{U}}_{{{95}}}\) and the a20 index. Each of these metrics offers a unique perspective on the model’s performance. R2 is a measure of how much of the dependent variable’s variance can be predicted from the independent variables, which lies in the range of 0 to 1, where a higher R2 value indicates better model performance and greater predictive accuracy. WMAPE measures the accuracy of a model by comparing the absolute error to the actual values, weighted by the magnitude of the actual values. Lower WMAPE values indicate better performance. The Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency measures how well the predicted values match the observed data. NS values range from -∞ to 1, where 1 indicates perfect prediction. The RMSE measures the average magnitude of the errors between the predicted and observed values. Lower RMSE values indicate better model performance. VAF measures the proportion of variance explained by the model. Higher VAF values indicate better performance. The performance index combines multiple error metrics into a single value, with lower values indicating better performance. The Willmott index assesses the degree of agreement between the predicted and observed values. The range of values for WI is from 0 to 1, with higher values suggesting a stronger level of cooperation. Without considering the direction of the errors, the mean absolute error (MAE) compares the average magnitude of the errors in a set of forecasts. MAE values that are lower suggest that the model is performing better. The results of the training and testing stages are summarized in Table 7, which includes the performance indicators that were acquired.

Based on these findings, the constructed MARS model achieved the highest prediction accuracy with performance metrics of \(R^{2} = 0.9642,WMAPE = 0.1287,NS = 0.9641,RMSE = 0.0440,4\) \(VAF = 96.4125,PI = 1.8819,WI = 0.9908,U_{95} = 0.2344,MAE = 0.0334\) and a20 index = 0.8438 in the training phase. The second-best performing model, MPMR, achieved performance metrics of \(R^{2} = 0.9551,WMAPE = 0.1745,NS = 0.9366,RMSE = 0.0584,\) \(VAF = 95.3850,PI = 1.8469,WI = 0.9831,U_{95} = 0.2275,MAE = 0.0453\) and a20 index = 0.7292, in the training phase. For the GMDH model, the performance metrics were \(R^{2} = 0.9227,WMAPE = 0.1870,NS = 0.9211,RMSE = 0.0652,\) \(VAF = 92.2720,PI = 1.7751,WI = 0.9792,U_{95} = 0.2345,MAE = 0.0486\) and a20 index = 0.6354, and for the FN model, \(R^{2} = 0.9102,WMAPE = 0.1825,NS = 0.9089,RMSE = 0.0700,\) \(VAF = 90.9947,PI = 1.7441,WI = 0.9760,U_{95} = 0.2369,MAE = 0.0474\) and a20 index = 0.6979.

However, in the testing set, the performance metrics for the MARS model were \(R^{2} = 0.9439,WMAPE = 0.1367,NS = 0.9431,RMSE = 0.0575,\) \(VAF = 94.3122,PI = 1.8050,WI = 0.9856,U_{95} = 0.2526,MAE = 0.0411\) and a20 index = 0.8333. Similarly, the second-best-performing model, MPMR, yielded performance metrics of \(R^{2} = 0.9408,WMAPE = 0.1549,NS = 0.9247,RMSE = 0.0661,\) \(VAF = 92.4778,PI = 1.7735,WI = 0.9775,U_{95} = 0.2178,MAE = 0.0466\) and a20 index = 0.7917. For the GMDH model, the performance metrics were, \(R^{2} = 0.9235,WMAPE = 0.1520,NS = 0.9203,RMSE = 0.0680,\)\(VAF = 92.0867,PI = 1.7429,WI = 0.9778,U_{95} = 0.2339,MAE = 0.0457,\) and a20 index = 0.6667, and for the FN model, \(R^{2} = 0.9082,WMAPE = 0.1644,NS = 0.9060,RMSE = 0.0738,\) \(VAF = 90.6274,PI = 1.7004,WI = 0.9759,U_{95} = 0.2561,MAE = 0.0494\) and a20 index = 0.7500.

In conclusion, the comprehensive evaluation of the developed MARS model against other models demonstrates its superior performance in both the training and testing phases. With the highest coefficients of determination and other favorable performance metrics, the MARS model proves to be the most accurate and reliable among the evaluated models. The MPMR model follows as the second most accurate, with the GMDH and FN models trailing thereafter. Moreover, both the MARS and MPMR models exhibited exceptional performance across various indices, including R2, NS, VAF, PI, WI, RMSE, MAE, WMAPE, \({\text{U}}_{{{95}}}\) , and the 20-index. These results highlight the MARS model’s potential for effective application in predictive UCS of CLSM mixes, emphasizing its robustness and generalizability.

UCS prediction of CLSM mixes via ML models

The analysis of the performance of four predictive models, MARS, FN, GMDH, and MPMR, highlights significant differences in their accuracy and generalization capabilities, particularly in predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes. The MARS model achieves the highest level of accuracy during the training phase, with an RMSE = 0.0440 and R2 = 0.9642 (refer to Fig. 19). These metrics indicate that MARS effectively captures the underlying patterns within the training data, resulting in minimal error and a high correlation between the predicted and actual values. However, when evaluated on the testing data, MARS shows a slight degradation in performance, with an RMSE of 0.0575 and an R2 of 0.9439. Despite this decline in R2, it remains within acceptable limits, indicating that the model still maintains robust predictive ability, as evidenced by the high R2 value during testing. In contrast, the FN model results in greater errors and lower predictive accuracy during both the training and testing phases. During training, the FN has an RMSE of 0.0700 and an R2 of 0.9102, indicating a less accurate model with greater variability in the predictions of the UCS of the CLSM mixes. Performance further deteriorates during testing, with an increase in RMSE to 0.0738 and a decrease in R2 to 0.9082. This significant decrease in R2 during testing suggests that the FN model struggles to generalize well to unseen data, making it less reliable for accurate predictions of the UCS of CLSM mixes. The GMDH and MPMR models, which fall between MARS and FN, also demonstrate satisfactory performance in both the training and testing phases. The RMSE values for MPMR and GMDH are 0.0584 and 0.0652, respectively, and the R2 values are 0.9551 and 0.9227, respectively, during the training phase. In the testing phase, the RMSE values for MPMR and GMDH increase to 0.0661 and 0.0680, respectively, while the R2 values are 0.9408 and 0.9235, respectively. In terms of the scatter plots, the data points predicted by the MARS model are within 15% of the absolute error from the equality line (i.e., the x = y line). However, for the FN, MPMR, and GMDH models, a few predicted data points fall beyond the 15% absolute error line. Overall, the MARS model consistently outperforms the FN, GMDH and MPMR methods in both the training and testing phases, making it the most effective model for predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes. The comparative analysis via scatter plots, as shown in Fig. 19, visually supports these findings, demonstrating the superior alignment of MARS predictions with actual values.

Residual plot

A residual plot is a key graphical tool in regression analysis and predictive modeling and is used to examine the differences between observed and predicted values from a statistical model. By plotting the residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values) against the predicted values or other variables, analysts can visually assess how well a model fits the data. An ideal residual plot displays residuals randomly scattered around zero, indicating that the model’s predictions are unbiased and that it effectively captures the underlying patterns within the data. Patterns or systematic structures in the residual plot might suggest model misspecification, such as omitted variables, incorrect functional forms, or heteroscedasticity.

In the analysis under discussion, residuals were calculated for various models, and their distributions are depicted in Fig. 20. A statistical analysis of these residuals indicated that their distribution approximates normality, with a mean (μ) close to zero. Notably, the standard deviations (σ) of the residuals for the MARS model on both the training and testing sets are 0.054 and 0.075, respectively, which are closer to those of the MPMR model. The values obtained for the MARS and GMDH models are significantly smaller than the standard deviations observed for the FN and GMDH models. The smaller mean and standard deviation imply that MARS and MPMR yield more consistent predictions, reflecting lower variability in the errors and therefore higher reliability. These findings suggest that the MARS and MPMR outperform the FN and GMDH models in predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes.

Ranking based on comprehensive measurement

One strategy for rating machine learning models on the basis of several different performance indicators is known as the comprehensive measure (COM) method68. There is a high probability that a single performance statistic will not provide an accurate depiction of the model that performs the best. As a result, the COM approach was utilized in this investigation to provide a comprehensive evaluation. This was accomplished by simultaneously merging R2, RMSE, and MAPE metrics into a parameter that was more efficient and valuable. A more comprehensive evaluation of a model’s overall performance can be obtained through the utilization of this method, which takes into account the possibility of conflicts among individual indicators. To determine the COM, Eq. (9) is utilized:

In the development of the predictive model, weights were allocated to each metric according to their significance in influencing the output. Specifically, a weight distribution of one third was applied during the training phase, and a weight distribution of two thirds was applied during the testing phase. This particular distribution was selected to facilitate substantial insights into the model’s ability to generalize, thereby ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the results. A lower COM value signifies enhanced overall model performance.

The outcomes of the COM analysis are presented in Table 8. Among the models evaluated, the MARS model attained the lowest COM value of 1.296, indicating superior performance. This was followed by the MPMR model, with a COM value of 1.681; the GMDH model, with a COM value of 1.986; and the FN model, with a COM value of 2.094. Therefore, the MARS model outperforms the MPMR, GMDH, and FN models.

REC curve

To analyze the predictive performance of the proposed models, the regression error characteristic (REC) curve was employed for both the training and testing phases. The REC curve serves as a robust graphical tool for evaluating regression models, particularly in scenarios where varying costs are associated with prediction errors. This method extends the concept of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, which is traditionally used in classification tasks, to regression tasks, where it has gained widespread application among researchers31. The construction of the REC curve begins with the selection of an appropriate error metric, such as the RMSE, or another relevant measure. Following this, the error for each prediction made by the proposed regression models is calculated. These errors are then sorted in ascending order. The REC curve is plotted by mapping the cumulative count of errors that are less than or equal to a specified threshold against the cumulative proportion of data points. The overall performance of the regression model can be summarized by calculating the area over the curve (AOC). A lower AOC value indicates superior predictive performance, with an ideal model achieving an AOC of 0.

In this study, the REC curves for all the proposed models in the training and testing phases were generated and are presented in Figs. 21 and 22. Additionally, the AOC values for both phases are depicted in Fig. 23. The results indicate that the proposed MARS model exhibits superior performance in predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes, followed by the MPMR, GMDH and FN models. Specifically, the MARS model achieved the lowest AOC values of 0.032 during training and 0.039 during testing. These values were followed closely by those of the MPMR model (0.044 for training and 0.043 for testing), the GMDH model (0.047 for training and 0.042 for testing), and the FN model (0.045 for training and 0.046 for testing). This performance hierarchy underscores the efficacy of the MARS model in this specific application of UCS prediction for CLSM mixes.

Sensitivity analysis

Assessing the robustness and reliability of machine learning models is critically dependent on sensitivity analysis. This technique offers valuable insights into a model’s robustness and accuracy by examining how variations in input variables influence output, i.e., the UCS of CLSM mixes. In this study, the most effective model, MARS, was subjected to sensitivity analysis, which is detailed in this section. The cosine amplitude method (CAM)69, a prevalent approach, was used to investigate the influence of input parameters on the UCS of CLSM mixes. Equation (10) is used to quantify each variable’s impact, where \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) denotes the impact correlation; \({\text{d}}_{{{\text{ik}}}}\) and \({\text{p}}_{{\text{k}}}\) represent the ith input and output parameters, respectively; and n is the number of datasets analyzed.

The results of the sensitivity analysis are presented in Fig. 24. Considering the results presented here, the parameter cement is the most significant parameter with \({\text{R }} = \, 0.{88}\), followed by water, flowability, pond ash, the curing period, and the fines content, with R values of 0.82, 0.79, 0.78, 0.73, and 0.68, respectively. The parameters of fly ash have the least significant impact on \(R\; {\text{value}}\; {\text{around}}\; 0.55\). The relative importance indices \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) are also illustrated in Fig. 25. Similarly, the parameter cement is the most significant input parameter with \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}} = { 17}\%\) , compared to approximately 16% for water. Flowability, pond ash, and the curing period have similar effects on the UCS of CLSM mixes with \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) below 14%. Fines content and fly ash have the least significant impact on \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) values of 13% and 10%, respectively.

Conclusion

The UCS of CLSM mixes of coal ash-based flowable fillers was predicted via four advanced regression models: MARS, FN, GMDH, and MPMR. The UCS-based dataset was obtained from laboratory experiments. The UCS prediction model was constructed via six input variables, namely, the cement content, fine content, pond ash content, fly ash content, water content added to the mixes, flowability, and curing period, with the UCS serving as the output variable. Various performance metrics were evaluated and compared to assess the accuracy and generalization capability of the developed machine learning models. Additionally, sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the significance of each input variable in predicting the UCS of the CLSM mixes. The key findings of this study are summarized below:

-

(1)

The high flowability of the PA1-based CLSM mix at 300 mm enhances its pumpability characteristics. It can be concluded that achieving 200 mm and 300 mm flowability requires increasing the W/C ratio, especially as the cement content and ash fines content increase, with ratios ranging from 10 to 47, which are higher than those of typical concrete mixes.

-

(2)

The dry unit weight of the CLSM mixes increased with increasing cement content for both the 200 mm and 300 mm flowability samples, as shown in Fig. 8, although a relatively fine ash content resulted in relatively low dry unit weight values. UCS testing revealed that a minimum of 2% cement was required to harden the PA1-based mixes after 24 h, and the UCS values increased with increasing cement content but decreased with increasing W/C ratio. The stress‒strain curves indicated a brittle failure pattern, with failure stresses between 0.9% and 1.8%, which was influenced by the type of ash, cement content, and flowability of the mix.

-

(3)

The variation in UCS values for different CLSM mixes over various curing periods reveals a significant increase in strength within the first 28 days. Beyond this period, the rate of strength gain slows, with minimal changes in UCS observed with extended curing.

-

(4)

The proposed models, namely, MARS, FN, GMDH, and MPMR, demonstrate a high degree of accuracy in predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes prepared from coal ash-based flowable fills. The UCS values predicted by these models closely correspond to the experimental UCS values obtained from laboratory tests during both the training and testing phases. Notably, the MARS model outperforms the FN, GMDH, and MPMR models, with higher accuracy in both training (\(R^{2} = 0.9642, VAF = 96.4125, \;and\; PI = 1.8819\)) and testing (\(R^{2} = 0.9439, VAF = 94.3122, and PI = 1.8050\)). Additionally, the residual error distribution histogram for the MARS model shows a normal distribution, with lower mean and standard deviation values compared to the other models, further emphasizing its superior predictive performance.

-

(5)

The machine learning models were ranked via the comprehensive measure (COM) technique, which provides a more holistic evaluation of model performance by considering various metrics such as R2, RMSE, and MAPE, among others. The MARS model had the lowest COM value of 1.296, indicating superior performance compared with the MPMR (1.681), GMDH (1.986), and FN (2.094) models.

-

(6)

The sensitivity analysis results revealed that cement is the most significant parameter for predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes, with an R value of 0.88, followed by water, flowability, pond ash, curing period, and fines content, with R values of 0.82, 0.79, 0.78, 0.73, and 0.68, respectively. The fly ash parameter has the least significant impact on the UCS of the CLSM mixes, with an R value of approximately 0.55.

-

(7)

The REC demonstrated that the MARS model outperformed the other models in predicting the UCS of the CLSM mixes, as indicated by the lowest AOC values of 0.032 during training and 0.039 during testing. These result highlights the effectiveness of the MARS model, followed by the MPMR, GMDH, and FN models, in predicting the UCS of CLSM mixes for this specific applications.

In future research, the priority should be to collect a more extensive dataset to enhance the training of machine learning models, which will subsequently improve the accuracy and reliability of predictions. A larger dataset would provide a broader range of examples for the models to learn from, enabling them to generalize to unseen data better and reduce prediction errors. This is particularly crucial in the context of predicting the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) of controlled low-strength material (CLSM) mixes, where the variability in material properties can significantly impact model performance. Additionally, the scope of the predicted indicators should be broadened to include a wider array of material properties beyond the UCS of CLSM mixes. Expanding the predictive focus to include parameters such as the setting time, bleeding rate, and elastic modulus would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the material behavior. Setting time, for example, is a critical factor in construction scheduling, while the bleeding rate affects the mix’s durability and surface finish. The elastic modulus is a key indicator of a material’s stiffness and ability to deform under loading. By incorporating these additional parameters into predictive models, researchers can develop a more holistic and accurate representation of CLSM mixes, which would be valuable for optimizing mix designs and ensuring material performance in real-world applications.

The study’s limitations include the following: (i) the dataset used was relatively small, which may affect the robustness and generalizability of the predictive models, leading to potential overfitting and limited performance on unseen data; given the short training dataset, the proposed models may overfit; (ii) the study focused on a limited set of input variables and did not include other potentially influential factors, such as setting time, bleeding rate, and elastic modulus, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of CLSM mix behavior; (iii) the models’ sensitivity to input changes can also impair their robustness, as small changes in input variables might drastically modify the models’ projections, impacting UCS estimates. To improve UCS forecasts for CLSM mixtures, future studies must increase the dataset, add material attributes, and explore novel modeling methods; (iv) although the MARS model performs best among those evaluated, future research should explore a broader range of machine learning algorithms and a more extensive dataset to further improve prediction accuracy and model reliability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bin-Shafique, S., Edil, T. B., Benson, C. H. & Senol, A. Incorporating a fly-ash stabilised layer into pavement design. Proc. Inst. Civil Eng. Geotech. Eng. 157, 239–249 (2004).

Gollakota, A. R. K., Volli, V. & Shu, C. M. Progressive utilisation prospects of coal fly ash: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 672, 951–989 (2019).

Do, T. M. et al. Fly ash: Production and utilization in India-an overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 279, 535–548 (2020).

Sharma, R. K. & Hymavathi, J. Effect of fly ash, construction demolition waste and lime on geotechnical characteristics of a clayey soil: A comparative study. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–11 (2016).

Romeekadevi, M. & Tamilmullai, K. Effective utilization of fly ash and pond ash in high strength concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 3, 1–7 (2015).

Bhatt, A. et al. Physical, chemical, and geotechnical properties of coal fly ash: A global review. Case Stud. Construct. Mater. 11, e00263 (2019).

ACI 229R-99. Controlled Low-Strength Materials. American Concrete Institute vol. 99 (2005).

Dev, K. L. & Robinson, R. G. Pond ash based controlled low strength flowable fills for geotechnical engineering applications. Int. J. Geosynthet. Ground Eng. 1, (2015).

Hardjito, D., Sin, W., & Why, S. W. On the use of quarry dust and bottom ash as controlled low strength materials (CLSM). in Proceedings of the Concrete 2011 Conference, Perth, Australia (2011).

Naganathan, S., Razak, H. A. & Hamid, S. N. A. Properties of controlled low-strength material made using industrial waste incineration bottom ash and quarry dust. Mater. Des. 33, 56–63 (2012).

Dev, K. L. & Robinson, R. G. Pond ash–based controlled low-strength materials for pavement applications. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 8, 101–116 (2019).

Zhen, G., Zhou, H., Zhao, T. & Zhao, Y. Performance appraisal of controlled low-strength material using sewage sludge and refuse incineration bottom ash. Chin J. Chem. Eng. 20, 80–88 (2012).

Hossain, K. M. A., Lotfy, A., Shehata, M. & Lachemi, M. Development of flowable fill products incorporating cement kiln dust. In 32nd Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures (2007).

Lachemi, M., Hossain, K. M. a., Shehata, M. & Thaha, W. Controlled low strength materials incorporating cement kiln dust from various sources. Cem. Concr. Compos. 30, 381–392 (2008).

Türkel, S. Long-term compressive strength and some other properties of controlled low strength materials made with pozzolanic cement and Class C fly ash. J. Hazard Mater. 137, 261–266 (2006).

Hwang, C. L. et al. Properties of alkali-activated controlled low-strength material produced with waste water treatment sludge, fly ash, and slag. Constr. Build Mater. 135, 459–471 (2017).

Sahu, BK Swarnadhipan, K. Use of botswana fly ash as flowable fill. Innovations in Controlled Low Strength Material, ASTM STP 1459, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA 41–50 (2004).

Lee, K.-J., Kim, S.-K. & Lee, K.-H. Flowable backfill materials from bottom ash for underground pipeline. Materials 7, 3337–3352 (2014).

Won, J.-P., Park, C.-G., Lee, Y.-S. & Park, H.-G. Durability characteristics of controlled low-strength materials containing recycled bottom ash. Mag. Concrete Res. 56, 429–436 (2004).

Razak, H.A Naganathan, S. Hamid, S. N. A. Controlled low-strength material using industrial waste incineration bottom ash and refined kaolin. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 35, 53–67 (2010).

Naganathan, S., Razak, H. A. & Hamid, S. N. A. Corrosivity and leaching behavior of controlled low-strength material (CLSM) made using bottom ash and quarry dust. J. Environ. Manage 128, 637–641 (2013).

Yan, D. Y. S., Tang, I. Y. & Lo, I. M. C. Development of controlled low-strength material derived from beneficial reuse of bottom ash and sediment for green construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 64, 201–207 (2014).

Du, L., Folliard, K. K. J. & Drimalas, T. Effects of additives on properties of rapid-setting controlled low-strength material mixtures. ACI Mater. J. 109, 21–30 (2012).

Gassman, SL Pierce, C. S. A. Effects of prolonged mixing and re-tempering on properties of controlled low strength materials. ACI Mater. J. 98, 194–199 (2001).

Maithili, K. L. A study of different materials used, suggested properties and progress in CLSM. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 05, 245–249 (2018).

Lin, D.-F., Luo, H.-L., Wang, H.-Y. & Hung, M.-J. Successful application of CLSM on a weak pavement base/subgrade for heavy truck traffic. J. Performance Const. Fac. 21, 70–77 (2007).

Boschert, J. & Butler, J. CLSM as a pipe bedding: Computing predicted load using the modified marston equation. in ASCE Pipelines 2013 Conference 1201–1212 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413012.112.

Alhomair, S. et al. A study of the engineering properties of CLSM with a new type of slag. Constr. Build Mater. 286, 201–207 (2021).

Do, T. manh, Kim, Y. sang & Ryu, B. cheol. Improvement of engineering properties of pond ash based CLSM with cementless binder and artificial aggregates made of bauxite residue. Int. J. Geo-Eng. 6, 1–10 (2015).

Kumar, S., Rai, B., Biswas, R., Samui, P. & Kim, D. Prediction of rapid chloride permeability of self-compacting concrete using multivariate adaptive regression spline and minimax probability machine regression. J. Build. Eng. 32, 101490 (2020).

Kumar, D. R. et al. Soft-computing techniques for predicting seismic bearing capacity of strip footings in slopes. Buildings 13, (2023).

Kumar, M. & Samui, P. Reliability analysis of pile foundation using GMDH, GP and MARS. in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering vol. 203 1151–1159 (Springer, 2022).

Kumar, M. & Samui, P. Reliability analysis of settlement of pile group in clay using LSSVM, GMDH, GPR. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 6717–6730 (2020).

Kumar, M. & Samui, P. Reliability analysis of pile foundation using ELM and MARS. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 3447–3457 (2019).

Kumar, R., Samui, P. & Rai, B. Prediction of the splitting tensile strength of manufactured sand based high-performance concrete using explainable machine learning. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01401-0.

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete and ultrahigh-performance concrete using soft computing techniques: A critical review. Struct. Concrete (2024).

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. A comparative study of adaboost and k-nearest neighbor regressors for the prediction of compressive strength of ultra-high performance concrete. in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering (eds. Goel, M. D., Kumar, R. & Gadve, S. S.) vol. 52 23–32 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2024).

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Machine learning techniques for prediction of failure loads and fracture characteristics of high and ultra-high strength concrete beams. Innov. Infrast. Solut. 8, 219 (2023).

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. A comparative study of prediction of compressive strength of ultra-high performance concrete using soft computing technique. Struct. Concrete https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202200850 (2023).

Khan, K. et al. Multi expression programming model for strength prediction of fly-ash-treated alkali-contaminated soils. Materials 15, (2022).

Khan, K., Salami, B. A., Iqbal, M. & Amin, M. N. Compressive strength estimation of fly ash/slag based green. 15, (2022).

Onyelowe, K. C., Jalal, F. E., Onyia, M. E., Onuoha, I. C. & Alaneme, G. U. Application of gene expression programming to evaluate strength characteristics of hydrated-lime-activated rice husk ash-treated expansive soil. Appl. Comput. Intell. Soft Comput. 2021, (2021).

Usama, M. et al. Predictive modelling of compression strength of waste GP/FA blended expansive soils using multi-expression programming. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 131956 (2023).

Zhao, G. et al. Predicting engineering properties of controlled low-strength material made from waste soil using optimized SVR models. Case Stud. Construct. Mater. 20, (2024).

Shin, Y. et al. Utilization of artificial interior stone sludge as fine aggregate in controlled low-strength material (CLSM). J. Build. Eng. 71, (2023).

Ray, R., Choudhary, S. S. & Roy, L. B. Reliability analysis of soil slope stability using MARS, GPR and FN soft computing techniques. Model Earth Syst. Environ. 1–11 (2022).

Biswas, R., Rai, B., Samui, P. & Roy, S. S. Estimating concrete compressive strength using MARS LSSVM and GP. Eng. J. 24, 41–52 (2020).

Biswas, R., Rai, B., Samui, P. & Roy, S. S. Estimating concrete compressive strength using MARS. LSSVM and GP. Engineering Journal 24, 41–52 (2020).

Ray, R. et al. Reliability analysis of reinforced soil slope stability using GA-ANFIS, RFC, and GMDH soft computing techniques. Case Stud. Construct. Mater. 18, e01898 (2023).