Abstract

This is a prospective case-control study investigated the factors influencing ultra-early visual acuity and quality after Small Incision Lenticule Extraction (SMILE) surgery, with a specific focus on the morphology and distribution of “black clefts” observed in posterior lenticule laser scanning images. A total of 174 patients who underwent SMILE surgery were included, and their preoperative ocular clinical parameters, visual quality indicators, and posterior lenticule laser scanning images were analyzed. The morphological features of black clefts were calculated using image processing techniques. Univariate and multivariate logistic analyses were conducted to identify factors impacting ultra-early visual acuity recovery, while correlation analysis was used to explore the association between black cleft morphology and postoperative visual quality. The results showed that although patients experienced significant visual acuity improvement one day after surgery, 26% had poor early recovery. Postoperative visual quality parameters were significantly lower, while the Object Scatter Index (OSI) was higher compared to preoperative values. Patients with poor visual recovery had a higher number of irregular black clefts in their laser scanning images. Logistic regression analysis revealed that intraoperative morphological parameters of black clefts were independent factors influencing early postoperative visual acuity recovery. Additionally, correlation analysis demonstrated a negative correlation between black cleft morphology and postoperative visual quality parameters, and a positive correlation with OSI. In conclusion, the morphology and distribution of black clefts during SMILE surgery significantly affect ultra-early postoperative visual acuity and quality, with increased variability in black cleft area leading to higher OSI, thereby impacting visual quality recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the continuous progress and development of myopia refractive surgery, the Small Incision Lenticule Extraction (SMILE) surgery utilizing femtosecond laser for small incisions and extraction of corneal tissue, which was introduced in 2011, has gradually become the most mainstream corneal refractive surgery method1,2. Compared to previous methods such as Femtosecond Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis (FS-LASIK) and Trans-Epithelial Photorefractive Keratectomy (TPRK), SMILE surgery has many irreplaceable advantages. It is minimally invasive, flapless, preserves in parts the integrity of the cornea, promotes faster healing of corneal nerve fibers, does not significantly interfere with biomechanical strength, and has a lower incidence of dry eye syndrome3,4,5. However, studies have found that the visual acuity and quality of vision recovery in the ultra-early (within 24 h postoperatively) and early stages (1 week to 3 months postoperatively) after SMILE surgery are relatively slow. Research by Liu et al. indicated that within 24 h post-SMILE surgery, patients had poorer uncorrected visual acuity and quality compared to those undergoing FS-LASIK6. Another study by Han Chen and colleagues showed increased occurrences and severity of blurred vision, glare, halos, and fluctuations in visual symptoms one month after SMILE surgery7, affecting the daily lives and visual experiences of patients in the early stages post-surgery.

Factors influencing the ultra-early and early visual acuity and quality of vision after all-femtosecond laser surgeries have become a focus of attention for both medical professionals and patients. Previous studies have identified various potential factors related to early visual acuity and vision quality after SMILE surgery, including preoperative factors such as age, refractive status, pupil size, Kappa angle, corneal curvature, and dry eye symptoms; intraoperative factors like opaque bubble layer (OBL), black areas, effective optical zone, corneal cap, laser energy; and postoperative factors such as surgery-induced dry eye, corneal inflammation, wound healing response, and complications8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Most existing research focuses on the early stages of post-SMILE surgery and primarily involves single-factor studies. However, there is limited research on factors affecting ultra-early visual acuity and vision quality after SMILE surgery. Additionally, our team’s preliminary research found that through deep learning models, using femtosecond laser scanning images or videos, it is possible to predict the visual recovery results 24 h post-SMILE surgery15. In analyzing femtosecond laser scanning images, it was observed that compared to the anterior lenticule laser scan image, posterior lenticule laser scanning images exhibit areas of black noise with diverse distribution characteristics. We defined these areas of black noise as “black clefts.” In contrast to previous studies that observed the smoother front surface of the lenticule under light microscopy compared to the back surface, where the back surface appeared brush-like and irregular under light microscopy, with numerous tissue bridges and discontinuous collagen fibers visible under scanning electron microscopy16,17,18. Therefore, we speculate that the formation of black clefts is due to tissue bridges between femtosecond laser points or discontinuous collagen fibers.

The morphology and distribution of black clefts on the posterior lenticule and their impact on visual acuity recovery and vision quality after SMILE surgery are poorly understood. Therefore, in this study, we utilized image processing techniques to segment black clefts in posterior lenticule laser scanning images, automatically calculate their morphological features, and comprehensively analyze potential factors affecting ultra-early visual acuity and vision quality recovery after SMILE surgery in conjunction with preoperative ocular clinical parameters and visual quality indicators.

Methods

Study subjects

This study is a prospective case-control study, in which 174 eyes of 174 patients who underwent small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) surgery at the Refractive Surgery Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University between November 2022 and May 2023, were consecutively enrolled. There were 68 male and 106 female patients, with an age range of 17 to 39 years. Each patient’s left eye was included in the research analysis (174 eyes). Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged from 18 to 45 and with myopia or astigmatism. (2) Stable refractive status for at least 2 years, with refractive change within 2 years ≤ -0.50D, spherical equivalent ranging from − 3.00 to -6.00D, cylinder ≤ -3.00D, preoperative best-corrected visual acuity ≤ 0 (LogMar), and no significant ocular or systemic diseases affecting vision. (3) Discontinuation of soft contact lenses for ≥ 1 week, soft toric contact lenses and rigid gas permeable lenses for ≥ 3 weeks, and orthokeratology lenses for ≥ 3 months. (4) Transparent cornea without opacity, injury, surgery history, or genetic diseases. (5) No history of other eye diseases such as glaucoma, retinal diseases, or uveitis. (6) Patients willing to follow up regularly. Exclusion criteria: (1) Age below 18 years. (2) History of active ocular diseases, trauma, or ocular genetic diseases. (3) Patients with severe amblyopia. (4) Patients with moderate to severe dry eye syndrome. (5) Patients with keratoconus, corneal ectasia, corneal opacity, or keratitis. (6) Patients with thin corneas, with expected residual stromal bed thickness after lenticule extraction < 250 μm. (7) History of systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic connective tissue diseases, etc. (8) Patients with psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression. (9) Exclusion of all patients who developed postoperative surgery-related complications in any femtosecond laser-assisted procedures. This study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Preoperative examination

All patients undergoing SMILE surgery underwent dry eye-related screening before surgery, including the Chinese Dry Eye Questionnaire survey, break-up time (BUT), Schirmer I test, and corneal fluorescein staining examination. Additionally, routine ophthalmic examinations were performed, including uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA), slit-lamp examination, manifest refraction, fundus examination, non-contact tonometry for intraocular pressure measurement(IOP), and measurements obtained from the Oculus Pentacam (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), including central corneal thickness (CCT), pupillary diameter (PD), corneal diameter (CD), Kappa angle, and anterior chamber depth (ACD). Oculus Keratograph 5 M (Oculus Optikgeräte GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to analyze tear meniscus height (TMH), noninvasive Keratograph tear breakup time (NIKBUT), lipid layer examination, meibomian gland orifice imaging, meibography (Meibo scan), and red eye scanning. In addition, the OQAS-II instrument (Visiometrics, Castelldefels, Spain) was used to assess visual quality parameters for SMILE surgery patients, including Modulation Transfer Function (MTF), Strehl Ratio (SR), Object Scatter Index (OSI), Predicted Visual Acuity (VA100% [daytime], VA20% [twilight], and VA9% [night]).

Surgical procedure

The surgeries for all patients included in this study were conducted by principal surgeons who possess over a decade of experience at the Refractive Surgery Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Three days before surgery, patients were administered antibiotic eye drops: 0.5% levofloxacin eye drops (Levofloxacin) and artificial tears: 0.1% sodium hyaluronate eye drops (Hylo-Comod), instilled four times daily in the surgical eye. After ocular disinfection during surgery, the ocular surface was anesthetized using proparacaine hydrochloride eye drops. SMILE surgery was performed using the VisuMax system (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) to create a corneal lenticule. The parameters were set as follows: frequency of 500 kHz, energy of 110-120nJ, spot spacing of 3 μm, cap diameter of 8 mm, lenticule thickness of 100–110 μm, optical zone (lenticule diameter) of 6.0–6.5 mm, and incision size of 2 mm, with the right eye incision at the 11 o’clock position and the left eye incision at the 12 o’clock position. After completion of the laser scanning of the patient’s operative eye, the negative pressure suction ring was removed, and the lenticule’s anterior and posterior surfaces were separated using microforceps, followed by complete removal of the lenticule under a surgical microscope. After lenticule extraction, the corneal cap was smoothed with a sterile sponge. Postoperatively, the surgical eye was examined with a slit lamp to confirm no abnormalities before the patient could leave. Postoperative medication included antibiotic eye drops: 0.5% levofloxacin eye drops (Santen, Japan) four times daily for one week; steroid eye drops: 0.1% Tobramycin dexamethasone (Alcon, China) four times daily for three days, followed by 0.5% Loteprednol Etabonate eye drops (Bausch & Lomb Incorporated, China) three times daily for one week, with a reduction of once weekly until one month postoperatively; and preservative-free artificial tears (0.1% sodium hyaluronate) applied four times daily for three months.

Scanning image acquisition and segmentation

Firstly, SMILE surgery videos were obtained from the VisuMax machine, and the OpenCV-python library was used to extract clear and complete posterior lenticule laser scanning images for subsequent analysis. The extracted scanning images were annotated and segmented for black noise areas (“black clefts”) using Image-J software (version 1.50i), and the OpenCV-python library was utilized to automatically calculate morphological features of the black clefts, including quantity, area, diameter, perimeter, and area coefficient of variation (CV). A simplified operational calculation process is shown in Fig. 1A.

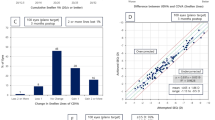

Image processing and Clinical outcomes of SIMLE surgery. (A) A streamlined flowchart illustrating the image processing. (B) Comparison between postoperative uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) and preoperative corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA). (C) Variation in preoperative CDVA compared to postoperative UDVA. (D) Relationship between attempted spherical equivalent (SE) refraction change and achieved SE refraction change. E: Distribution of postoperative accuracy in spherical equivalent refraction.

Postoperative follow-up

One day postoperatively, all patients underwent a follow-up examination, including slit-lamp examination, manifest refraction, UCVA, IOP measurement, corneal topography using the Oculus Pentacam, and postoperative visual quality assessment using OQAS-II.

Statistical analysis

Due to the interdependence of measurements between both eyes of each patient, only data from the left eye were utilized for analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using either R version 4.2.2 or GraphPad Prism version 9, following these steps:1) Continuous data parameters were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk (SW) test, where P > 0.05 indicated normal distribution and P ≤ 0.05 indicated non-normal distribution; 2) For normally distributed data, descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation(SD), and paired t-tests were performed. For non-normally distributed data, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) was employed for statistical description, and the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test was utilized; 3) Categorical variables underwent analysis using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test; 4) Variables demonstrating significant differences in univariate logistic analysis were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis.5) Spearman’s correlation test was employed for correlation analysis. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05 for all tests.

Results

Baseline data

In this study, a total of 174 myopic patients (174 eyes) who underwent SMILE surgery were included, with 68 male patients and 106 female patients. The age range was 18 to 39 years, with a median age of 26 years. The preoperative uncorrected distance visual acuity (logMAR) had a median of 1.22 (IQR: 1.10, 1.22). The preoperative spherical equivalent (SE) had a median of -4.50D (IQR: -5.12D, -3.75D), with a median spherical power of -4.25D (IQR: -4.75D, -3.50D) and a cylindrical power of -0.50D (IQR: -0.75D, -0.25D). The mean axial length (AL) was 25.20 ± 0.85 mm (mean ± SD). The median corneal diameter (CD) was 11.60 (IQR: 11.40, 11.90) mm. The median pupil diameter (PD) was 2.90 (IQR: 2.68, 3.21) mm. The Kappa angle was 0.15 (IQR: 0.10, 0.21) mm. The corneal thickness (CCT) was 547.00 (IQR: 526.00, 561.00) µm. The range of mean keratometry (Km) was 43.01D ± 1.35D, with the steep keratometry (K1) range of 42.53D ± 1.37D and the flat keratometry (K2) range of 43.55D ± 1.38D. The average anterior chamber depth (ACD) was 3.15 ± 0.25 mm. The average intraocular pressure was 16.09 ± 2.37mmHg (Table 1).

Postoperative visual acuity results and changes in visual quality

Upon review one day postoperatively, we found that 98.85% of eyes achieved uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) equal to or better than 0.1 (Fig. 1B). Notably, 96.70% of eyes maintained or improved their UDVA compared to preoperative corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) (Fig. 1C). The best-fit curve for achieved vs. attempted spherical equivalent (SE) on the first postoperative day was Y = 0.98X + 0.18 (Fig. 1D). When comparing preoperative SE with target refraction, 74% of eyes were within ± 0.50D, and 93% were within ± 1.00D (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, postoperative visual quality parameters including MTF, SR, OSI, VA100%, VA20%, and VA9% showed significant differences (P < 0.001) compared to preoperative values (Table 2).

Morphological analysis of the black clefts in scanning images

A total of 174 high-quality posterior lenticule laser scanning images were extracted from SMILE surgery videos. Based on the visual acuity status on the first postoperative day, the eyes were divided into a group with good visual recovery (LogMAR UCVA ≤ 0) (Fig. 2A) and a group with poor visual recovery (LogMAR UCVA > 0) (Fig. 2B) for comparative analysis to evaluate the differences in morphological features of the black clefts between the two groups. It was surprising to find that the group with poor visual recovery had significantly higher values in num_count (Fig. 2C), area_max (Fig. 2D), area_mean (Fig. 2E), diameter_max (Fig. 2F), diameter_mean (Fig. 2G), perimeter_max (Fig. 2H), perimeter_mean (Fig. 2I), and area_ratio (Fig. 2J) compared to the group with good visual recovery. Although there was no statistical difference in area_cv between the two groups, the average value in the poor visual recovery group was notably higher than that in the good visual recovery group (Fig. 2K).

Example images and Differential analysis. (A) Example of posterior lenticule laser scanning images and corresponding segmentation of black clefts in good visual recovery group. (B) Example of posterior lenticule laser scanning images and corresponding segmentation of black clefts in poor visual recovery group. (C-K) The box plots of num_count (2), area_max (D), area_mean (E), diameter_max (F), diameter_mean (G), perimeter_max (H), perimeter_mean (I), and area_ratio (J) between good and poor visual recovery groups.

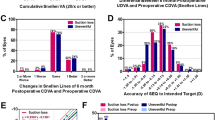

Comparison of baseline data and analysis of postoperative visual quality

A comparison and analysis of baseline data between the good visual recovery group and the poor visual recovery group revealed statistically significant differences in VA100% (1.40 [1.10; 1.60] vs. 1.20 [1.00; 1.50]) and VA20% (0.98 ± 0.27 vs. 0.87 ± 0.31) between the groups, while other clinical parameters showed no significant differences (Table 3). Additionally, the comparison of differences in postoperative visual quality parameters between the groups showed that OSI scores were significantly higher in the poor recovery group compared to the good recovery group (Fig. 3A). However, there was no significant difference in the change in visual quality parameters (Preoperative-Postoperative) between the two groups (Fig. 3B).

Differential analysis of visual quality. (A) The box plots of visual quality parameters (MTF, SR, IOS, VA100%, VA20%, VA9%) between good and poor visual recovery groups. (B) The differential analysis of delta visual quality parameters (MTF, SR, IOS, VA100%, VA20%, VA9%) between good and poor visual recovery groups. ** means P < 0.01; ns mean not significant.

Logistic analysis

To study the influence of preoperative and intraoperative parameters on early postoperative visual acuity, univariate logistic analysis was conducted on preoperative clinical data, preoperative visual quality, and morphological features of the black clefts. It was found that preoperative visual quality parameters including MTF (OR: 1.46, P = 0.03), SR (OR: 1.46, P = 0.03), OSI (OR: 0.64, P = 0.01), VA100% (OR: 1.48, P = 0.02), VA20% (OR: 1.52, P = 0.02), and VA9% (OR: 1.46, P = 0.04), as well as intraoperative morphological parameters including num_count (OR: 0.50, P = 0.00), area_max (OR: 0.70, P = 0.04), area_mean (OR: 0.64, P = 0.01), diameter_max (OR: 0.69, P = 0.03), diameter_mean (OR: 0.60, P = 0.00), perimeter_max (OR: 0.72, P = 0.05), perimeter_mean (OR: 0.60, P = 0.00), and area_ratio (OR: 0.51, P = 0.00) were potential factors affecting early postoperative visual acuity recovery (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, only num_count (OR: 0.14, P = 0.05), area_max (OR: 0.05, P = 0.03), area_mean (OR: 223.93, P = 0.04), diameter_mean (OR: 0.03, P = 0.02), and perimeter_mean (OR: 0.02, P = 0.02) showed statistical differences when included in multivariable logistic analysis (Fig. 4B).

Correlation analysis between morphological parameters and postoperative visual quality

Correlation analysis was conducted between the morphological parameters of the black clefts and postoperative visual quality parameters, revealing a negative correlation between area_cv, area_max, area_mean, diameter_max, diameter_mean, perimeter_max, perimeter_mean, and postoperative visual quality parameters such as MTF, VA100%, and VA20%, while showing a positive correlation with OSI (Fig. 5A). Additionally, a correlation analysis of the change values in visual quality parameters found a significant positive correlation between area_cv and delta_OSI, and significant negative correlations with delta_MTF, delta_VA100%, and delta_VA20% (Fig. 5B).

Correlation analysis and Construction of regression model. (A) The heatmap of correlation for morphological features with visual quality parameters. (B) The heatmap of correlation for morphological features with delta visual quality parameters. (C) The values of Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for 9 machine-learning methods. (D) The values of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for 9 machine-learning methods. (E) The values of R Squared for 9 machine-learning methods. (F) The architecture of the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) model (G) The distribution of Shap values for 9 machine-learning methods. (H) The correlation between predict and actual OSI in training dataset. (I) The correlation between predict and actual OSI in testing dataset. (J) The correlation between predict and actual OSI in all dataset.

The close relationship between the morphological features of the black crack during surgery and postoperative visual quality led us to consider whether machine learning techniques could be utilized to predict postoperative OSI values. The eyes were randomly divided into training and testing sets at a ratio of 70%:30%. Nine machine learning techniques (Decision Tree, ElasticNet, KNN, lightGBM, Linear regression, SVM, MLP, RandomForest, and XGboost) were employed to construct regression models in the training set, utilizing 5-fold cross-validation and grid searching for optimal hyperparameters. The models were then evaluated in the testing set based on Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R Squared parameters. Among the models, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) exhibited the lowest RMSE = 1.3 (Fig. 5C) and MAE = 0.98 (Fig. 5D), while having the highest R Squared = 0.09 (Fig. 5E). The architecture of the MLP model consisted of a single hidden layer neural network with 15 neurons (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, visualization sorting based on Shape values revealed that area_cv, perimeter_max, and area_max held the most significant weights in the model predictions (Fig. 5G). The correlation between predicted and actual OSI values in the training set (Fig. 5H), test set (Fig. 5I), and the entire dataset (Fig. 5J) were 0.44 (P = 0.00), 0.27 (P = 0.05), and 0.39 (P = 0.00), respectively.

Discussion

In recent years, the prevalence of myopia has been increasing year by year, especially among young adults, with an annual incidence rate ranging from 10–20%19. An increasing number of patients are choosing corneal refractive surgery to correct refractive errors, and Small Incision Lenticule Extraction (SMILE) surgery has become the mainstream procedure20,21. Although SMILE surgery offers advantages such as minimal invasiveness, flapless technique, preservation of corneal integrity, faster healing of corneal nerve fibers, better biomechanical strength, and reduced dry eye symptoms, previous studies have shown that the visual recovery in the ultra-early and early postoperative periods is poorer compared to FS-LASIK, leading to significant visual symptoms and affecting the early postoperative quality of life for patients6,22. Current research efforts mainly focus on studying the early visual acuity and visual quality recovery after SMILE surgery, with most studies investigating the impact of single factors on postoperative visual acuity. However, there is limited research specifically targeting the ultra-early postoperative period (within 24 h after surgery). In this study, clinical research was conducted on 174 patients who underwent SMILE surgery, collecting preoperative and intraoperative data, and performing multifactor analysis to investigate their impact on ultra-early postoperative visual acuity and visual quality.

Comparing postoperative and preoperative data of the patients, it was observed that the equivalent spherical power significantly decreased and the visual acuity improved on the first day after surgery, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). The distribution of the postoperative equivalent spherical power was within ± 1.00D for 93% of the patients and within ± 0.50D for 74% of the patients. On the first day after surgery, the patients’ visual acuity improved from LogMAR UCVA of 1.22 (1.10, 1.22) preoperatively to LogMAR UCVA of 1.00 (0.80, 1.00) postoperatively. The distribution of postoperative visual acuity was LogMAR UCVA ≤ 0.2 for 100%, LogMAR UCVA ≤ 0.1 for 98.85%, LogMAR UCVA ≤ 0 for 74%, logmar UCVA ≤ -0.1 for 13%, and logmar UCVA ≤ -0.2 for 1.7%. Among the patients, 39.08% had no change in CDVA after surgery, 42.53% had an improvement of 1 line, 14.37% had an improvement of 2 lines or more, 2.3% had a loss of 1 line, and 1.72% had a loss of 2 lines. These findings are consistent with most previous studies and indicate that SMILE surgery has significant effectiveness in correcting myopia, but approximately 26% of patients (logmar UCVA > 0) experience poor early visual recovery.

In addition to postoperative visual acuity, the evaluation of postoperative visual quality after SMILE surgery also includes factors such as high-order aberrations (HOAs), spherical aberration (SA), and coma, which may affect visual quality. Recent studies have reported that early postoperative visual symptoms such as blurred vision, halos, glare, and visual fluctuations can occur after SMILE surgery, and these symptoms can affect patients’ dynamic visual acuity7,10,23. For the analysis of visual quality, the study utilized the OQAS-II visual analysis instrument, which is a dual-channel technology-based device that quantitatively evaluates the aberrations, scattering, and diffraction of the patient’s visual pathway, providing a comprehensive assessment of visual quality and allowing accurate evaluation of pre- and postoperative visual quality in SMILE patients24,25. By emitting a point light source, the instrument projects light through the eye’s refractive media onto the retina, and the reflected light is collected by the device, from which the Point Spread Function (PSF) is obtained. Further analysis of the PSF yields visual quality-related parameters such as MTFcutoff, SR, OSI, VA100%, VA20%, and VA9%. The study found that on the first day after surgery, the visual quality-related parameters MTF, SR, VA100%, VA20%, and VA9% were significantly lower, while OSI was significantly higher compared to preoperative values, with statistically significant differences (P< 0.05). This indicates that visual quality in the ultra-early postoperative period is reduced compared to preoperative levels, which is consistent with previous research6,26. This decrease may be related to factors such as the roughness of the corneal interface after the lenticule is removed, early inflammatory reactions, and disrupted tear film stability in the early postoperative period.

To study the roughness of the corneal interface, the study analyzed the femtosecond laser scanning videos during SMILE surgery and found a large number of scattered black clefts in the posterior lenticule laser scanning images compared to the anterior scanning images. The appearance of black clefts may be attributed to the difference in density of the corneal stroma at different locations. It is well known that the cornea’s structure is not uniform, with the anterior one-third of the stroma being denser than the deeper two-thirds27,28. When the femtosecond laser scans the posterior stroma, the ratio of the vertical radius to the horizontal radius of the resulting bubbles is greater in anterior regions. The fusion plane formed by incomplete bubble fusion results in numerous tissue bridges, which can break and detach during lenticule separation and removal, leading to a rough interface. Similarly, previous studies using slit-lamp and retroillumination to observe rough corneal interfaces immediately after SMILE surgery29. Additionally, scanning electron microscope images have shown that the anterior surface of the lenticule is smoother, while the posterior surface is rougher with visible scattered tissue bridges and disrupted collagen fibers17. The study further analyzed the morphological parameters of the black clefts in the posterior lenticule laser scanning images and found that the number, area, diameter, and perimeter of black clefts were significantly higher in the group with poor visual recovery compared to the group with good recovery. This demonstrates that the quality of posterior laser scanning during surgery directly affects the visual outcomes on the first day after surgery. Furthermore, the study found a negative correlation between the area, diameter, perimeter, and coefficient of variation of black clefts and the MTF, VA100%, and VA20% postoperatively, consistent with previous research. This indicates a significant negative correlation between interface roughness and postoperative MTF and SR29. The study also found a significant positive correlation between the coefficient of variation and the maximum diameter of black clefts and the OSI postoperatively. In other words, larger black clefts and greater variation in area are associated with an increased likelihood of higher OSI in the corneal stromal interface. This further confirms that the morphological parameters of black clefts in the posterior laser scanning images reflect the roughness of the corneal interface. The study concludes that the more numerous and irregular the black clefts, the greater the increase in corneal stray light, resulting in decreased light transmission and a close correlation with the scattering index OSI. An increase in OSI can lead to decreases in MTF, SR, and contrast visual acuity. This is consistent with previous research, which indicates that OSI in SMILE patients temporarily increases postoperatively and then returns to normal after three months30,31,32.

Furthermore, a multivariable logistic regression model was used to analyze the patients’ baseline data, dry eye grades, visual quality, and morphological parameters of black clefts during surgery. The study found that the appearance of black clefts during posterior laser scanning was an independent factor influencing postoperative visual acuity. However, baseline data such as age, preoperative refractive error, corneal curvature, and Kappa angle were found to be insignificant factors. Possible reasons for this include adjustments made using a nomogram before surgery and the inclusion of only moderate myopia patients, which controlled for the bias caused by different refractive errors. Additionally, patients with moderate to severe dry eye were excluded based on expert consensus guidelines.

In comparison to previous studies, this research has several advantages. Firstly, while previous studies required tools such as slit-lamps, confocal microscopes, and scanning electron microscopy to investigate the impact of SMILE surgery on the roughness of the corneal interface, this study only required analysis of the quality of intraoperative scanning images. Secondly, the study quantitatively analyzed the morphological parameters of black clefts, laying the foundation for further research. Lastly, a single-hidden-layer neural network was constructed to roughly predict the value of postoperative OSI based on the morphological parameters of black clefts during surgery. However, this study still has limitations. Firstly, it is a single-center retrospective study, and secondly, the sample size is small with a relatively short follow-up period. Furthermore, factors influencing the morphology of black clefts were not further investigated, and the accuracy of the predictive model has not reached a clinically usable level. Therefore, future research should focus on expanding the sample size, increasing the number of centers, extending the follow-up period, and further investigating the impact of laser energy parameters and corneal biomechanics on the morphology of black clefts.

In conclusion, the posterior laser scanning of the lenticule during SMILE surgery is a major factor affecting ultra-early postoperative visual acuity and visual quality. The morphological parameters of black clefts during surgery are closely related to postoperative visual quality, and greater variation in area leads to an increase in the scattering index (OSI), which impacts the recovery of ultra-early postoperative visual quality.

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Huang, G. & Melki, S. Small incision Lenticule extraction (smile): Myths and realities. Semin Ophthalmol. 36, 140–148 (2021).

Sekundo, W., Kunert, K. S. & Blum, M. Small incision corneal refractive surgery using the small incision lenticule extraction (smile) Procedure for the correction of myopia and myopic astigmatism: Results of a 6 Month prospective study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 95, 335–339 (2011).

Ahmed, A. A. & Hatch, K. M. Advantages of small incision lenticule extraction (smile) for mass eye and ear special issue. Semin Ophthalmol. 35, 224–231 (2020).

Reinstein, D. Z. et al. Small incision Lenticule extraction (smile) for the correction of high myopia with astigmatism. J. Refract. Surg. 38, 262–271 (2022).

Zhang, H., Deng, Y., Li, Z. & Tang, J. Update of research progress on small incision lenticule extraction (smile) lenticule reuse. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 1423–1431 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Visual and optical quality outcomes of smile and Fs-Lasik for Myopia in the very early phase after surgery. BMC Ophthalmol. 19, 88 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. The dynamic changes and influencing factors of visual symptoms after small incision Lenticule extraction. BMC Ophthalmol. 23, 223 (2023).

Fu, M. et al. Long-term visual quality after small incision lenticule extraction (smile) and laser assisted subepithelial keratomileusis (Lasek) for low myopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 22, 347 (2022).

Gyldenkerne, A., Ivarsen, A. & Hjortdal, J. Optical and visual quality after small-incision lenticule extraction. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 45, 54–61 (2019).

Lin, M. et al. Comparison of small incision lenticule extraction and transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy in terms of visual quality in myopia patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 99, e1289–e96 (2021).

Ma, K. K. & Manche, E. E. Corneal sensitivity and patient-reported Dry Eye symptoms in a prospective randomized contralateral-Eye Trial comparing laser in situ keratomileusis and small incision lenticule extraction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 241, 248–253 (2022).

Miao, H. et al. Visual quality after femtosecond laser small incision lenticule extraction. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Phila) 6, 465–468 (2017).

Yang, X. et al. Long-term visual quality and pupil changes after small-incision lenticule extraction for eyes without preoperative cylinder refraction. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 8835585 (2024).

Zhang, J. H. et al. The best optical zone for small-incision Lenticule extraction in high myopic patients. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 46, 1302–1307 (2020).

Wan, Q. et al. Prediction of early visual outcome of small-incision lenticule extraction (smile) based on deep learning. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12, 1263–1279 (2023).

Kunert, K. S. et al. Surface quality of human corneal lenticules after femtosecond laser surgery for myopia comparing different laser parameters. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249, 1417–1424 (2011).

Wei, S. et al. The study of the changes of ultra- microstructure after a momentary action of femtosecond laser with human corneal tissue in vivo. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 51, 520–526 (2015).

Ziebarth, N. M. et al. Surface quality of human corneal lenticules after smile assessed using environmental scanning Electron Microscopy. J. Refract. Surg. 30, 388–393 (2014).

Rahi, J. S., Cumberland, P. M. & Peckham, C. S. Myopia over the lifecourse: Prevalence and early life influences in the 1958 British birth cohort. Ophthalmology 118, 797–804 (2011).

Moshirfar, M. et al. Small-incision lenticule extraction. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 41, 652–665 (2015).

Titiyal, J. S. et al. Small incision Lenticule extraction (smile) techniques: Patient selection and perspectives. Clin. Ophthalmol. 12, 1685–1699 (2018).

Lin, Q., Shen, Z. & Zhou, X. Intensive topical steroid regimen for enhanced very early recovery after small incision lenticule extraction. Int. Ophthalmol. 43, 4097–4103 (2023).

Chiche, A. et al. Early Recovery of Quality of Vision and Optical Performance after refractive surgery: Small-incision lenticule extraction versus laser in situ Keratomileusis. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 44, 1073–1079 (2018).

Ren, Z. et al. Assessment of Visual Quality in eyes with Forme Fruste Keratoconus and mild and moderate Keratoconus based on Optical Quality Analysis System Ii parameters. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 7505016 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Comparative study of objective visual quality between Fs-lasik and smart in myopia. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 15, 502–509 (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. Comparison of the optical quality after smile and Fs-lasik for high myopia by oqas and itrace analyzer: A one-year retrospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 21, 292 (2021).

Agca, A. et al. Corneal backscatter analysis by in vivo confocal microscopy: Fellow eye comparison of small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted lasik. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 265012 (2014).

Knox Cartwright, N. E., Tyrer, J. R., Jaycock, P. D. & Marshall, J. Effects of variation in depth and side cut angulations in lasik and thin-flap lasik using a femtosecond laser: A biomechanical study. J. Refract. Surg. 28, 419–425 (2012).

Ganesh, S., Brar, S., Pandey, R. & Pawar, A. Interface Healing and its correlation with visual recovery and quality of Vision following small incision lenticule extraction. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 66, 212–218 (2018).

Miao, H. et al. Optical quality and intraocular scattering after femtosecond laser small incision lenticule extraction. J. Refract. Surg. 30, 296–302 (2014).

Wei, S. et al. Ultrastructural changes and corneal wound healing after smile and prk procedures. Curr. Eye Res. 41, 1316–1325 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Corneal remodeling after smile for moderate and high myopia: Short-term assessment of spatial changes in corneal volume and thickness. BMC Ophthalmol. 23, 402 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhi Xing Shi Jie-Ophthalmic Clinical Research Support Project (No. BFC-KECS-LC-20220930-3) and the Health Commission of Sichuan Province Medical Science and Technology Program (No.24LCYJPT20).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QW conducted the analysis and drafted the original manuscript, while TLQ, RW reviewed the relevant articles. HBY, JT, KM, and YPD developed the idea for the paper. All authors provided feedback and approved the final text.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The research adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, Q., Qian, T., Wei, R. et al. Posterior lenticule laser scan influence the ultra-early postoperative visual acuity and quality of SMILE. Sci Rep 14, 27072 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78080-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78080-4