Abstract

The 5’ cap, catalyzed by RNA guanylyltransferase and 5’-phosphatase (RNGTT), is a vital mRNA modification for the functionality of mRNAs. mRNA capping occurs in the nucleus for the maturation of the functional mRNA and in the cytoplasm for fine-tuning gene expression. Given the fundamental importance of RNGTT in mRNA maturation and expression there is a need to further investigate the regulation of RNGTT. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is one of the most abundant RNA modifications involved in the regulation of protein translation, mRNA stability, splicing, and export. We sought to investigate whether m6A could regulate the expression and activity of RNGTT. In this short report, we demonstrated that the 3’UTR of RNGTT mRNA is methylated with m6a by the m6A writer methyltransferase 3 (METTL3). Knockdown of METTL3 resulted in reduced protein expression of RNGTT. Sequencing of capped mRNAs identified an underrepresentation of ribosomal protein mRNA overlapping with 5’ terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) mRNAs, and genes are dysregulated when cytoplasmic capping is inhibited. Pathway analysis identified disruptions in the mTOR and p70S6K pathways. A reduction in RPS6 mRNA capping, protein expression, and phosphorylation was detected with METTL3 knockdown

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 5’ cap, which consists of an N7-methylated guanosine molecule, is covalently added to the first transcribed nucleotide by the mRNA capping enzyme RNGTT1. The 5’ cap coordinates the downstream functions of mRNAs, and is required for protein translation, mRNA stability, splicing, and export2. The 5’ cap is canonically added in the nucleus to all RNAs transcribed by RNA Polymerase II3. In the nucleus, RNGTT, along with RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase (RNMT)4 and its coactivator RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase activating subunit (RAMAC)5 interacts with the C-terminal domain of RNA Polymerase II to add the 5’ cap during the initial stages of transcription6. mRNA capping is also detected in the cytoplasm7 where RNGTT, RNMT-RAMAC, and an unknown 5’monophosphatase is bound to the scaffold protein NCK18,9. In the cytoplasm, the cap of uncapped mRNAs10 and long noncoding RNAs11 are restored by the cytoplasmic capping complex, serving as a regulatory mechanism to fine-tune gene expression10.

In addition to its basic function in mRNA maturity, RNGTT has been linked to biological and pathological processes such as development12 and certain cancers13. RNGTT was shown to positively modulate the Hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting PKA kinase activity in Drosophila development. The mammalian homolog of RNGTT was shown to have the same function in Drosophila and cultured mammalian cells12. The oncogene c-MYC recruits RNGTT to RNA Polymerase II during transcription; the cell proliferation of c-MYC overexpressing cells is reduced with the downregulation of RNGTT, while cells with normal c-MYC levels were unaffected14. Furthermore, RNGTT was upregulated in high-eIF4E acute leukemia patients , and increased mRNA capping of MYC, CDK2, and MALAT1 was detected15. Given the observed importance of RNGTT, there is a need to better understand regulatory pathways of mRNA capping to investigate other biological functions of RNGTT.

A possible regulatory pathway for capping involves epitranscriptomic modifications of RNGTT mRNA such as m6A. m6A, one of the most abundant modifications in RNAs16, is a dynamic marker in RNAs that is added by m6A writers, removed by m6A erasers, and recognized by m6A readers to undergo its functional role17. m6A modification in mRNAs has been associated with enhanced protein translation, mRNA stability, splicing, export17, and linked to a wide range of biological processes17.

In this study, we identified and validated an m6A site in the 3’UTR of RNGTT mRNA. Using non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines as our model, we demonstrated a regulatory pathway where METTL3 directly methylates this region and affects the protein expression of RNGTT. We identified the disruption of mRNA capping on ribosomal protein mRNAs, and alterations of the mTOR and p70S6K signaling pathways.

Results

m6A modification of RNGTT 3’UTR by METTL3 regulates its protein expression

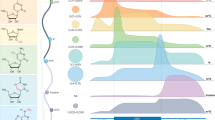

To predict whether METTL3 could regulate RNGTT mRNA, we performed data mining on the 3’UTR of RNGTT using the RNA EPItranscriptome Collection (REPIC)18. The m6A peak file (MeTPeak) for RNGTT was downloaded to determine the region in RNGTT that could contain m6A modifications (Table S1). We identified a region at the 3’UTR of RNGTT enriched in m6A pulldowns. The 3’UTR of RNGTT was then scanned for the consensus m6A motif of METTL3 DRACH16 using the FIMO motif scan tool19,20. Both datasets are represented as a genome track (Fig. 1A). The m6A motifs that were identified with FIMO are represented in Fig. 1A. To study the potential role of this m6A site of RNGTT, we generated A549 cells that stably express either a scramble shRNA (sh-) or shMETTL3. We performed western blot analysis probing for METTL3 and RNGTT and observed the reduction of METTL3 in shMETTL3 cells (Fig. 1B, Fig S1). RNGTT protein expression was reduced in shMETTL3 cells when compared to sh- cells (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1). We examined the mRNA expression of RNGTT by RT-PCR and observed no change in mRNA expression (Fig. 1C). Additionally, we verified that shMETTL3 cells have reduced global m6A levels compared to sh- (Fig. S2A). Interestingly, our stable cells did not have a significant reduction in the m6A levels of poly-A selected RNAs (Fig S2A). To monitor the change in the cellular state of our A549 shMETTL3, we verified the cell viability of A549 shMETTL3 cells by alamarBlue and MTS assays and observed a slight significant increase with both alamarBlue and MTS assay (Fig. S2B and C). Thus, our A549 shMETTL3 cells decrease METTL3 without any adverse changes in their cellular state. To confirm that METTL3 directly methylates RNGTT, m6A RNA immunoprecipitation followed by RT-qPCR was performed using primers for the predicted m6A motifs in RNGTT mRNA (Fig. 1D left). Both site 1 and site 2 regions of RNGTT mRNA were reduced in shMETTL3 compared to sh- after m6A immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1D right), confirming that METTL3 directly methylates RNGTT mRNA in the predicted site.

METTL3 regulates the expression and stability of RNGTT. (A) Genomic view of the 3’UTR of RNGTT. m6A pulldown peaks (REPIC) and METTL3 motif prediction (FIMO) are displayed as tracks in IgvR. (B) Representative western blot analysis of protein expression of METTL3, RNGTT, and loading control Vinculin done in triplicate. Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Band intensities were normalized to vinculin and sh- was set as 1. (C) mRNA levels of RNGTT analyzed by RT-qPCR normalized to GAPDH expression by ΔΔCT. Sh- was set to 1. Error bars represent S.E.M. in biological triplicates. * Represents student’s t-test p. value < 0.05. (D) m6A RNA immunoprecipitation on predicted site of m6A modification of RNGTT mRNA analyzed by RT-qPCR. Immunoprecipitation is represented as % input relative to recovery of m6A positive control. sh- was set to 100%. Error bars represent S.E.M. with biological replicates represented as a dot n ≥ 3. ** represents two-tailed student’s t-test p. value < 0.01. E) RNA stability assay in A549 sh-/shMETTL3 analyzed by RT-qPCR. RNA expression is represented as RNA levels normalized to GAPDH at the indicated timepoint relative to the RNA levels at timepoint 0 h in either sh- or shMETTL3. Error bars represent S.E.M. of biological replicates n = 4. * Represents two-tailed student’s t-test of sh- vs shMETTL3 p. value < 0.05 at each indicated timepoint, ** represents p. value < 0.01.

M6A modification can affect the RNA stability of the transcript17. We examined the RNA stability of RNGTT by a time course treatment with the RNA Polymerase II inhibitor 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (DRB)21. The DRB time course experiment showed the expected reduction of the RNA stability of METTL3 mRNA (sh- RNA half-life = 7.22 h, shMETTL3 RNA half-life = 4.10 h) (Fig. 1E left). The RNA stability of RNGTT is not changing in shMETTL3 cells (sh- RNA half-life = 7.00 h, shMETTL3 RNA half-life = 8.15 h), suggesting that the m6A site on RNGTT does not alter the RNA stability of RNGTT (Fig. 1E right).

Knockdown of METTL3 reduces the RNA capping of ribosomal proteins

The observed decrease of RNGTT with METTL3 knockdown raises the question of whether global mRNA capping would also be altered. Uncapped mRNAs are translationally inactive and are subject to 5’ RNA degradation2 or are stored in an uncapped state10. To test the global changes in capped mRNAs, we performed capped cDNA enrichment using TeloPrime 5’ cDNA kit (Lexogen) followed by next-generation sequencing in A549 sh- and shMETTL3 A549 cells (Fig. 2A). TeloPrime enriches capped mRNAs through double strand ligation of an adaptor with a cytosine overhang to the 5’ guanosine cap. Through PCR amplification of the adapter, capped mRNAs are amplified while uncapped mRNAs are excluded. The resulting cDNA represents the capped population of mRNAs which allows the precise analysis of differentially capped mRNAs. Interestingly, differential expression analysis of sh- vs. shMETTL3 A549 cells identified a subset of 411 dysregulated genes (≥ 1.5-fold change and p.val. < 0.01), despite the observed downregulation of RNGTT protein expression. The differentially capped mRNAs were distributed between 203 downregulated and 208 upregulated genes (Fig. 2B and Table S2).

Downregulation of METTL3 disrupts mRNA capping in select genes. (A) Schema of TeloPrime capped mRNA cDNA synthesis and DNAseq analysis. (B) Volcano plot on differentially expressed genes sh-/shMETTL3 A549. Grey points represent no significance (p. value > 0.01 and |Log2FC|< 0.58), green points represent |Log2FC|> 0.58, blue points represent p-value < 0.01, and red points represent significant genes (|Log2FC|> 0.58 and a p-value < 0.01). (C) Gene overlap between top mRNAs or cytoplasmic capped mRNAs and differentially expressed genes. Venn diagrams are scaled with list size. *** represents overlapping Fisher exact test p. value < 0.001. (D) Dot plot of the top 15 pathways identified by IPA for the downregulated capping genes. (E) Representative western blot analysis of protein expression of METTL3, RNGTT, P-RPS6, RPS6 and Ponceau staining as loading control done in triplicate. Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. Band intensities were normalized to ponceau stain, and scr- was set to 1. (F) CAP-IP on selected genes in PC9 cells analyzed by RT-qPCR. Data were first normalized to input and then normalized to housekeeping control ACTIN and represented as fold change with scr enrichment set as 1. Error bars represent S.E.M. in N = 7. Ns represents non-significant two-tailed student t-test of scr vs siMETTL3. * Represents two-tailed student’s t-test of scr vs siMETTL3 p. value < 0.05, ** represents p. value < 0.01.

We performed a protein class analysis through the PANTHER tool22,23 to identify the class of genes that were differentially capped in our sequencing data. The analysis identified translational and ribosomal proteins as underrepresented and scaffold/adaptor proteins as overrepresented (Table S3). Translational and ribosomal protein mRNA contain a 5’ Terminal Oligo Pyrimidine (TOP) motif24. TOP mRNAs are translationally regulated by La-related protein 1 (LARP1), which binds to both the TOP motif and the 5’cap25,26,27. We explored whether our differentially capped mRNAs shared similarities with TOP mRNAs identified using LARP1 RNA Immunoprecipitation performed in Gentilella et al.28. We found a significant overlap (p. val. 3.0 × 10^-26) of 45 genes between our data and TOP mRNAs (Fig. 2C top and Table S4). Additionally, a previous study demonstrated that TOP mRNAs were downregulated when cytoplasmic capping was inhibited29. When examining the cytoplasmic capped transcripts29, we observed a significant overlap (p. val. 1.5 × 10^-8) of 139 genes (Fig. 2C bottom and Table S4). RNGTT has been observed to be distributed into a nuclear and cytoplasmic population7. To test whether cytoplasmic RNGTT is also affected by METTL3 knockdown, we examined the subcellular localization of RNGTT by western blot in A549sh/shMETTL3. We observed a reduction of both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNGTT in the A549 shMETTL3 cells (Fig. S3). This data suggests that METTL3 can affect cytoplasmic capped mRNAs as was observed in the gene overlap.

To determine the possible functional role of the differentially capped mRNAs, we performed a gene set analysis through Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) for all genes and downregulated capped genes (Table S5). We focused on the pathways identified with the downregulated capped genes as these are more directly linked to the reduction of RNGTT (Fig. 2D), in particular, on the mTOR signaling pathway based on the activation of ribosomal protein translation through these pathways30. p70S6K is downstream of the mTOR pathway31 and directly phosphorylates RPS6, a marker of the activation of both pathways32. To test for the reduction of these two pathways, we performed a western blot on the phosphorylation of RPS6 with the knockdown of METTL3 A549 cells. We observed a reduction of P-RPS6 signal with siMETTL3(Fig. 2E, Fig. S4). Total RPS6 has a slight decreasing trend but not significant (Fig. 2E, Fig. S4). Taken together, the knockdown of siMETTL3 reduces the RNA capping of ribosomal proteins and impacts the phosphorylation of a downstream target of the mTOR and p70S6K signaling pathway.

METTL3 has been shown to have varying dependencies on different cell types33. To expand the observed relation between METTL3 and RNGTT, we transiently repressed METTL3 with siMETTL3 in an additional NSCLC cell line, PC9 (Fig. S5). We observed a decrease in RNGTT protein expression (Fig. S5A, Fig. S6), no significant change in RNGTT mRNA expression (Fig. S5B), and a decrease in m6A pulldown (Fig. S5C) as was observed in the A549 cell line. Interestingly, RNGTT mRNA stability in PC9 cells was decreased (scr- RNA half-life = 9.37 h, siMETTL3 RNA half-life = 7.53 h) (Fig. S5D) in contrast to what was observed in the A549 stable cells. Furthermore, we performed CAP-IP15 to assay the difference in the capping status of these genes when METTL3 is downregulated as an independent validation of the sequencing data in siMETTL3 transient transfection in PC9 cells. We focused on a selected set of downregulated ribosomal proteins, such as RPL7, RPL29, RPS6, and RPL13A (all with a fold change < -1.5). We observed a significant decrease of CAP-IP fold enrichment for RPL7, RPS6, and RPL29 (p.val > 0.05 for RPL7 and p. val. > 0.01 for RPS6 and RPL29) with no change in housekeeping gene GAPDH in siMETTL3 transfected PC9 cells (Fig. 2F). There was a decreasing trend of RPL13A, which was not statistically significant. Thus, the decrease in CAP-IP enrichment enforces the changes in differentially capped mRNAs observed in A549 cells.

Discussion

In addition to its function in mRNA maturation, RNGTT has been shown to play a role in biological function and disease13,14,15 which highlights the importance to investigate regulatory pathways such as epitranscriptomic modification of RNGTT. m6A is one of the most abundant epitranscriptomic modifications found in mRNAs16, added by the m6A writer METTL3. In this study, we identified METTL3 as a regulator of RNGTT. We datamined and validated a METTL3 motif in the 3’UTR of RNGTT (Fig. 1A). This site showed a reduction of m6A pulldown recovery when METTL3 is knocked down through shRNA. The knockdown of METTL3 resulted in reduced protein expression of RNGTT (Fig. 1B) and with no change in the mRNA expression of RNGTT (Fig. 1C). The RNA stability of RNGTT was unaffected in A549 shMETTL3 (Fig. 1E). In PC9 cells, however, the RNA stability of RNGTT was reduced with transient knockdown of METTL3 (Fig. S5D). This behavior can be explained by the adaptation of A549 cells with long term repression of METTL333. The reduction of RNGTT protein expression and no change in mRNA expression is consistent across both cell lines, thus the effect of METTL3 downregulation is more prominently acting on RNGTT translation. M6A is recognized by m6A readers which define the biological function of the m6A site17. Several m6A readers such as YTHDF134, YTHDF335, and YTHDC236 have been reported to affect the mRNA translation of their binding targets. The reduction of RNGTT m6A by METTL3 would reduce the binding of m6A readers and result in the reduced protein expression observed. Additionally, METTL3 itself has been shown to increase the protein translation of mRNAs independently of its m6A methylation activity37. Our findings do not exclude the possibility that other targets of METTL3 could affect the protein expression of RNGTT. Future studies are needed to identify the m6A reader that binds to RNGTT and to examine the contribution of additional factors to our observed effects of m6A in RNGTT.

We examined if METTL3 could alter the capping of mRNAs. Interestingly, the sequencing of capped mRNAs identified 411 genes with altered mRNA capping (Fig. 2B, Table S2), a smaller subset than what we expected with the observed downregulation of RNGTT. The differentially expressed genes had a similar distribution between 208 increased and 203 decreased genes. A similar distribution of dysregulated genes was observed when cytoplasmic capping was inhibited29. When performing a gene enrichment analysis using PANTHER, we identified ribosomal and translation proteins as underrepresented in our capped gene set; scaffold and adaptor proteins were overrepresented (Table S3). A previous study identified a subset of mRNAs, which includes ribosomal proteins and 5’ TOP mRNAs, with altered capping when cytoplasmic capping is inhibited29. We observed a significant overlap between cytoplasmic capping mRNAs and TOP mRNAs with our dataset (Fig. 2C bottom). Interestingly, both nuclear and cytoplasmic RNGTT were decreasing with knockdown of METTL3 (Fig. S3). The amount of differentially capped mRNAs identified is lower than expected, given the decrease of RNGTT in both compartments. This may be explained by the fact that, compared to cytoplasmatic capping, nuclear capping is critical for cellular gene expression and its activity in the nucleus may be retained and not be affected by protein downregulation to maintain cell viability.

IPA analysis of our differentially capped genes identified p70S6K signaling and the mTOR signaling pathway in the decreased capped mRNAs (Table S5, Fig. 2D) which is in line with the downregulation of TOP mRNAs in our sequencing. METTL3 has been shown to be a positive regulator for both the mTOR and p70S6K38,39. Additionally, RNGTT has been reported to transcriptionally regulate mTORC1, RPTOR, and RPS6 in the liver regeneration of zebrafish40. The reduced capping of downstream TOP mRNAs and the reduction of P-RPS6 signal (Fig. 2E, Fig. S4) suggests that METTL3 might contribute to the activation of mTOR and p70S6K through RNGTT. Alternatively, METTL3 has been reported to regulate mTORC1 through the m6A methylation of GLUT1 in colorectal cancer, highlighting a parallel regulatory effect of METTL3 on mTOR41. Future studies are needed to determine whether upstream components of the mTOR pathway are disrupted by the METTL3-RNGTT axis.

Because cell lines can vary on their dependency to METTL3 knockdown33, we expanded to an additional NSCLC cell line PC9. Knockdown of METTL3 in PC9 cells showed a reduction of RNGTT protein expression (Fig. S5A, Fig S6), no change in RNGTT mRNA expression (Fig S5B), and m6A pulldown enrichment (Fig. S5C). Interestingly, we observed a reduction in the RNA stability of RNGTT in PC9 cells (Fig. S5D). As an independent validation of the capped sequencing, we performed an anti-m7G pulldown on a select set of ribosomal proteins, normalizing for the input to eliminate changes in mRNA levels and for the housekeeping gene actin as our capping positive control. We observed a significant reduction in cap pulldown of RPL7, RPL29, and RPS6 (Fig. 2F). RPL13A capping was reduced but not significant. These results confirm the regulation of RNGTT by METTL3 in a second cell line and validate the observed reduction of ribosomal proteins for those assayed with CAP-IP.

We used NSCLC cell lines as a model to study the regulatory mechanism between METTL3 and RNGTT. Interestingly, the validated ribosomal protein RPL29, RPL7, and RPS6 have all been linked to hallmarks of cancer. RPL29 has been reported to be a regulator of angiogenesis in mice42. RPL7 is seen downregulated with cisplatin treatment in lung cancer43 and involved in microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer44. RPS6 is upregulated in NSCLC and its inhibition promotes cell cycle arrest45. The reduced capping of ribosomal proteins with METTL3 inhibition opens a new line of investigation into their role in cancer biology. Furthermore, the regulatory relationship between METTL3 and RNGTT should be deeply investigated in other biological contexts.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and cell line development

A549 and PC9 cell lines were obtained from the ATCC, verified by short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, and tested for mycoplasma contamination prior to use. A549 and PC9 cell lines were seeded and grown in RPMI (Sigma-Aldrich #R8758), supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma #F4135) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Quality Biological #120-095-721). Stable A549 cell lines were generated with transfection of sh- (SantaCruz #sc-108060) and shMETTL3 (SantaCruz #sc-92172) using Lipofectamine LTX (ThermoFisher # A12621). Stable cells were selected and grown in RPMI + 0.75 µg/mL of puromycin. All cells were synchronized with RPMI + 0.5% FBS prior to cell plating.

Western blot

Cells for protein extraction were lysed using RIPA lyses buffer (Sigma #R0278) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (cOmplete™, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Sigma #11,836,153,001; PhosSTOP™, Roche #4,906,845,001). Protein quantification was determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo- Fisher #23,225) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of protein lysates and rainbow molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad Laboratories #1,610,394) were separated by 7.5% SDS/PAGE (Bio-Rad #4,561,106) and then electro-transferred to 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad # 1,620,112). The membranes were blocked with a buffer containing 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.01% Tween20 (TBST) for at least 1 h and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C (anti-METTL3, ThermoFisher # 15,073-1-AP; anti-RNGTT, ThermoFisher # 12,430-1-AP; anti-Vinculin, Santa Cruz #sc-25336; anti-S6 Ribosomal Protein, Cell Signaling #5G10; anti-P-S6 Ribosomal Protein, Cell Signaling, D57.2.2E, anti-Lamin A/C, Cell Signaling, #4777). After three washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Antibody, Cell Signaling #7074; Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody, Cell Signaling #7076) and developed with a luminol-based enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate, Thermo Scientific™ #34,076). Images were obtained using ChemiDoc XRS + Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ v1.54 Fiji version.

Real-Time qRT-PCR

75,000 A549 sh-/shMETTL3 or transfected PC9 scr-/siMETTL3 in triplicate were plated into a 24-well plate. 24 h after plating (48 h for transfected PC9 cells). RNA was extracted using RNA Clean-Up and Concentration Kit (NORGEN #43,200) and eluted with 20 µl of H2O. 10 µl of eluted RNA and input RNA was retro transcribed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems™ #4,368,814). RT-qPCR was performed with Taqman® technology using the following probes: GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1) and RNGTT (Hs01016932_m1). Ct values were normalized to GAPDH using the ΔΔCT method.

Transfection

200,000 cells were seeded on a 6-well dish for 24 h before transfection. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (ThermoFisher # L3000015) following manufacture’s protocol. Cells were transfected either with negative control (scr-) (Santa Cruz #sc-37007) or siMETTL3 (ThermoFisher # 4,392,420). The media was changed after 5 h, and transfected cells were harvested after 48 h. Transfection efficiency was determined with reverse transcription of 500 ng of RNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems™ #4,368,814). RT-qPCR was then performed with Taqman® technology using the following probes: Actin (Hs99999903_m1), METTL3 (Hs00219820_m1).

m6A site prediction

m6A RNA immunoprecipitation peaks were datamined from the REPIC web browser (https://repicmod.uchicago.edu/repic/)18 for A549 cells (Table S1). MeTPeak for RNGTT was downloaded from REPIC (Table S1) and converted into Hg38 chromosome coordinates. The peaks were generated by REPIC using the SRA sample SRP022152 (Table S1). The 3’UTR of RNGTT was downloaded from Ensembl46 and scanned for the METTL3 motif DRACH using FIMO19,20 with a p-value cutoff of 0.001. Motif locations were converted into Hg38 chromosome coordinates and both the REPIC and FIMO coordinated were loaded into igvR (v1.18.0) for genome visualization.

Cell viability assays

3000 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate. After 24 h, either MTS (CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation assay, Promega #G5421) or alamar blue (alamarBlue Cell Viability Reagent, Invitrogen #DAL1025) was added to the wells. MTS was read after 30 min at wavelength 490 nm and alamar blue was read after 3 h at wavelength 600 nm and 570 nm.

Global m6A quantification

Global m6A levels were assayed using EpiQuik m6A RNA Methylation Quantification Kit (Colorimetric) (EpigenTek # P-9005-48) following manufacture’s protocol with 200 ng of total RNA and 50 ng of Poly-A selected RNA. Poly-A RNA was selected from total RNA using NEBNext® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs E749S) following manufacture’s protocol. Absolute m6A levels were determined through comparison of a standard curve with negative and positive m6A controls provided by the kit.

m6A RNA immunoprecipitation

7.5ug of total RNA was immunoprecipitated for m6A with EpiMark® N6-Methyladenosine Enrichment Kit (NEB) following the manufacture protocol. 10% of the sample RNA with 1ul of a 1:1000 mix of negative and positive m6A spike-in (provided by the kit) was taken as input prior to the pulldown. The eluted RNA was suspended with 1 mL TRIzol (Invitrogen #15,596,018) and purified using RNA Clean-Up and Concentration Kit (NORGEN #43,200) and eluted with 20 µl of H2O. 10 µl of eluted RNA and input RNA was retro-transcribed as described above. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR GreenER™ qPCR SuperMix for ABI PRISM™ Instrument (ThermoFisher # 11,760,100). Ct values for each m6A site were first normalized to input and then normalized to a positive m6A control as described in47. The primers used are the following: positive m6A control (FWD 5 ́- CGACATTCCTGAGATTCCTGG - 3, REV 5 ́- TTGAGCAGGTCAGAACACTG – 3’), negative m6A control (FWD 5 ́- GCTTCAACATCACCGTCATTG -3, REV 5 ́- CACAGAGGCCAGAGATCATTC - 3 ́), RNGTT site 1(FWD 5’-GAGCTCATGCCACCACCAC-3’, REV 5’-GCTACAAAAATGGGCAACAGCG-3’), RNGTT site 2 (FWD 5’-GCCAGCCTGTAAATACTTGATGC-3’, REV 5’-CAGATTCCACAAGGTAAGGCTG-3’).

RNA stability assay

RNA stability was assayed through a time-course inhibition of RNA Polymerase II with DRB21. 75,000 A549 sh-/shMETTL3 or transfected PC9 scr-/siMETTL3 in triplicate were plated into a 24-well plate. 24 h after plating (48 h for transfected PC9 cells), cells were treated with 20ug/mL of DRB and incubated at 37C, 5% CO2 for the indicated time points (0, 2, 4, 6,8 ,10 h). After the final timepoint, the media was aspirated from the wells, washed once with PBS, and cells were lysed with 1 mL of TRIzol. RNA was purified using RNA Clean-Up and Concentration Kit (NORGEN #43,200). 250 ng of RNA was retrotranscribed as described above. RT-qPCR was performed with Taqman® technology using the following probes: GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1), Actin (Hs99999903_m1), METTL3 (Hs00219820_m1), and RNGTT (Hs01016932_m1). Half-life measurements were calculated according to Chen et al.48.

TeloPrime

Capped mRNAs were enriched and converted to cDNA with TeloPrime Full-Length cDNA Amplification Kit V2 (Lexogen # 013.24). TeloPrime was performed on 2 µg of total RNA following the manufacturer’s protocol. 18 cycles for endpoint PCR were used for final cDNA amplification for all samples. The resulting cDNA was sent for DNAseq at Genomics Core facility at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and sequenced using NextSeq2000 Sequencer (Illumina).

Pre-processing

Raw sequencing reads in FASTQ format were quality trimmed, and adapters were removed using Trim Galore (v0.6.6) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Trimmed reads were then mapped to the human genome (HG38 assembly) using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)49. Afterward, the mapped reads in SAM format were converted into BAM format, sorted (for coordinates), and indexed using Samtools (v1.12)50. Finally, gene quantification was performed by FeatureCounts (v2.0.0)51 using Gencode (v39) GTF annotation file.

Differential expression analysis

To perform the differential gene expression (DE) analysis, we first scaled the raw read counts via Read Per Million (RPM) and filtered out low expressed genes, whose geometric mean value was less than five across all samples. Afterward, the raw read counts of the retained genes were first normalized by using the Trimmed Mean of M-values method and then log2-transformed leveraging the Voom function and then used for the DE analysis, leveraging the Limma R package (v3.48.3)52. Genes with a |Log2FC|> 0.58 (|Linear FC|> 1.5) and a p-value < 0.01 were considered differentially expressed. The volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes was generated using the EnhancedVolcano R package (v1.10.0).

Pathway analysis and Gene overlap analysis

Using Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA®) software (v01-22-01), we performed functional enrichment analysis considering the differentially expressed genes (mentioned above). Settings used for the IPA analysis included experimentally observed data for the human species. For gene overlap, the list of TOP mRNAs (labeled as RP and TOP) was extracted from Gentilella et al.28 and the statistically significant cytoplasmic capped mRNAs were extracted from del Valle-Morales et al.29. Gene overlap was performed using the GeneOveralp R package (v1.34.0) using default parameters. Venn diagrams were generated using the R package VennDiagram (v1.7.3)53.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear separation

1,000,000 A549 sh-/shMETTL3 cells were plated on a 60 mm dish. After 24 h, cells were harvested and pelleted in cold PBS by centrifugation (500 g for 10 min). The pellet was lysed for cytoplasmic and nuclear separation using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher #78,833). The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were quantified with BCA protein assay and western blot analysis was performed as described above.

CAP-IP

Capped mRNA was immunoprecipitated following the protocol described in Culjkovic-Kraljacic et al.15. 4 µg of total RNA spiked with 1 ng/µL of Luciferase Control RNA (Promega #L4561) as a negative uncapped control. 10% of RNA and spike-in was taken as input. Bound RNA was purified as described above. 10µL of bound RNA and 10% input was retro transcribed as described above. RT-qPCR was performed with Taqman® technology using the following probes: Actin (Hs99999903_m1), GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1), RPL7(Hs02596927_g1), RPS6(Hs04195024_g1), RPL13A (Hs04194366_g1), RPL29 (Hs06645107_g1). Pulldown efficiency was determined with RT-qPCR using SYBR GreenER™ qPCR SuperMix for ABI PRISM™ Instrument on Luciferase (primers FWD 5’-CTTATGCATGCGGCCGCATCTAGAGG-3’, REV 5’-CAGTTGCTCTCCAGCGGTTCCATCC-3’).

Statistics and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism (10.2.2) was used for statistical analysis. Bar graphs are represented as the mean with error bars represented as ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The outliers were removed by Grubbs’ test. The data was analyzed by Student’s t-test to compare two groups. PANTHER analysis was corrected by false discovery rate (FDR.). Gene overlaps were analyzed by fisher’s exact test in the GeneOveralp R package (v1.34.0). The number of replicates for each experiment are indicated on the figure legend. P. values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

The raw sequence data and the table with the raw counts are deposited in GEO (GSE273305).

References

Furuichi, Y. Discovery of m(7)G-cap in eukaryotic mRNAs. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 91, 394–409. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.91.394 (2015).

Galloway, A. & Cowling, V. H. mRNA cap regulation in mammalian cell function and fate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 270–279, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.09.011 (1862).

Ramanathan, A., Robb, G. B. & Chan, S. H. mRNA capping: Biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 7511–7526. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw551 (2016).

Pillutla, R. C., Yue, Z., Maldonado, E. & Shatkin, A. J. Recombinant human mRNA cap methyltransferase binds capping enzyme/RNA polymerase IIo complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21443–21446. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.34.21443 (1998).

Varshney, D. et al. mRNA cap methyltransferase, RNMT-RAM, promotes RNA Pol II-dependent transcription. Cell Rep. 23, 1530–1542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.004 (2018).

McCracken, S. et al. 5’-Capping enzymes are targeted to pre-mRNA by binding to the phosphorylated carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 11, 3306–3318. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.11.24.3306 (1997).

Otsuka, Y., Kedersha, N. L. & Schoenberg, D. R. Identification of a cytoplasmic complex that adds a cap onto 5’-monophosphate RNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 2155–2167. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01325-08 (2009).

Mukherjee, C., Bakthavachalu, B. & Schoenberg, D. R. The cytoplasmic capping complex assembles on adapter protein nck1 bound to the proline-rich C-terminus of Mammalian capping enzyme. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001933. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001933 (2014).

Trotman, J. B., Giltmier, A. J., Mukherjee, C. & Schoenberg, D. R. RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase catalyzes the methylation of cytoplasmically recapped RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 10726–10739. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx801 (2017).

Mukherjee, C. et al. Identification of cytoplasmic capping targets reveals a role for cap homeostasis in translation and mRNA stability. Cell Rep. 2, 674–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.011 (2012).

Mukherjee, A., Islam, S., Kieser, R. E., Kiss, D. L. & Mukherjee, C. Long noncoding RNAs are substrates for cytoplasmic capping enzyme. FEBS Lett. 597, 947–961. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.14603 (2023).

Chen, P. et al. Capping enzyme mRNA-cap/RNGTT regulates hedgehog pathway activity by antagonizing protein kinase A. Sci. Rep. 7, 2891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03165-2 (2017).

Borden, K., Culjkovic-Kraljacic, B. & Cowling, V. H. To cap it all off, again: Dynamic capping and recapping of coding and non-coding RNAs to control transcript fate and biological activity. Cell Cycle 20, 1347–1360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2021.1930929 (2021).

Lombardi, O., Varshney, D., Phillips, N. M. & Cowling, V. H. c-Myc deregulation induces mRNA capping enzyme dependency. Oncotarget 7, 82273–82288. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12701 (2016).

Culjkovic-Kraljacic, B. et al. The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E elevates steady-state m(7)G capping of coding and noncoding transcripts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 117, 26773–26783. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002360117 (2020).

Wei, C. M. & Moss, B. Nucleotide sequences at the N6-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 16, 1672–1676. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00627a023 (1977).

Jiang, X. et al. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6, 74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00450-x (2021).

Liu, S., Zhu, A., He, C. & Chen, M. REPIC: A database for exploring the N(6)-methyladenosine methylome. Genome Biol 21, 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02012-4 (2020).

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E. & Noble, W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39-49. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv416 (2015).

Grant, C. E., Bailey, T. L. & Noble, W. S. FIMO: Scanning for occurrences of a given motif. Bioinformatics 27, 1017–1018. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr064 (2011).

Harrold, S., Genovese, C., Kobrin, B., Morrison, S. L. & Milcarek, C. A comparison of apparent mRNA half-life using kinetic labeling techniques vs decay following administration of transcriptional inhibitors. Anal. Biochem. 198, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(91)90500-s (1991).

Thomas, P. D. et al. PANTHER: Making genome-scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Sci. 31, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.4218 (2022).

Mi, H. & Thomas, P. PANTHER pathway: An ontology-based pathway database coupled with data analysis tools. Methods Mol. Biol. 563, 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-175-2_7 (2009).

Avni, D., Biberman, Y. & Meyuhas, O. The 5’ terminal oligopyrimidine tract confers translational control on TOP mRNAs in a cell type- and sequence context-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.995 (1997).

Philippe, L., Vasseur, J. J., Debart, F. & Thoreen, C. C. La-related protein 1 (LARP1) repression of TOP mRNA translation is mediated through its cap-binding domain and controlled by an adjacent regulatory region. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 7604–7605. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa535 (2020).

Fonseca, B. D. et al. La-related protein 1 (LARP1) represses terminal oligopyrimidine (TOP) mRNA translation downstream of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15996–16020. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.621730 (2015).

Jia, J. J. et al. mTORC1 promotes TOP mRNA translation through site-specific phosphorylation of LARP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 3461–3489. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1239 (2021).

Gentilella, A. et al. Autogenous control of 5’TOP mRNA stability by 40S ribosomes. Mol. Cell 67, 55-70 e54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.005 (2017).

Del Valle Morales, D., Trotman, J. B., Bundschuh, R. & Schoenberg, D. R. Inhibition of cytoplasmic cap methylation identifies 5’ TOP mRNAs as recapping targets and reveals recapping sites downstream of native 5’ ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 3806–3815. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa046 (2020).

Magnuson, B., Ekim, B. & Fingar, D. C. Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signalling networks. Biochem. J. 441, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20110892 (2012).

Meyuhas, O. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: Four decades of research. Int. Rev. Cell. Mol. Biol. 320, 41–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.006 (2015).

Biever, A., Valjent, E. & Puighermanal, E. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation in the nervous system: From regulation to function. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8, 75. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2015.00075 (2015).

Poh, H. X., Mirza, A. H., Pickering, B. F. & Jaffrey, S. R. Alternative splicing of METTL3 explains apparently METTL3-independent m6A modifications in mRNA. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001683 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 (2015).

Shi, H. et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 27, 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2017.15 (2017).

Hsu, P. J. et al. Ythdc2 is an N(6)-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 27, 1115–1127. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2017.99 (2017).

Lin, S., Choe, J., Du, P., Triboulet, R. & Gregory, R. I. The m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol. Cell 62, 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.021 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. The m6A methyltransferase METTL14 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35, e23655. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23655 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. m(6) A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes retinoblastoma progression via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 24, 12368–12378. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15736 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Rngtt governs biliary-derived liver regeneration initiation by transcriptional regulation of mTORC1 and Dnmt1 in zebrafish. Hepatology 78, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000000186 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. RNA N(6)-methyladenosine methyltransferase METTL3 facilitates colorectal cancer by activating the m(6)A-GLUT1-mTORC1 axis and is a therapeutic target. Gastroenterology 160, 1284-1300 e1216. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.013 (2021).

Jones, D. T. et al. Endogenous ribosomal protein L29 (RPL29): A newly identified regulator of angiogenesis in mice. Dis. Model Mech. 6, 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.009183 (2013).

Ryan, S. L. et al. Identification of proteins deregulated by platinum-based chemotherapy as novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 11, 615967. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.615967 (2021).

Yu, C. et al. Identification of key genes and pathways involved in microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 19, 2065–2076. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2019.9849 (2019).

Chen, B. et al. Downregulation of ribosomal protein S6 inhibits the growth of non-small cell lung cancer by inducing cell cycle arrest, rather than apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 354, 378–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2014.08.045 (2014).

Cunningham, F. et al. Ensembl 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D988–D995. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1049 (2022).

McIntyre, A. B. R. et al. Limits in the detection of m(6)A changes using MeRIP/m(6)A-seq. Sci. Rep. 10, 6590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63355-3 (2020).

Chen, C. Y., Ezzeddine, N. & Shyu, A. B. Messenger RNA half-life measurements in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 448, 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02617-7 (2008).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 (2014).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: A package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The DNA sequencing data included in this study was generated at the Genomics Core facility at Virginia Commonwealth University. Diagrams were created with BioRender.com

Funding

Project supported by VCU Postdoctoral Independent Research Award (DDVM), American Lung Association (LCDA-922902) (GN, MA), National Institutes of Health (NIH 1R21CA277525-01; NIH 1R21CA287180-01A1) (GN, MA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DDVM and MA designed the study. DDVM, GR, PL, LM, MS, RB, AL, and GN coordinated and performed the experiments, and analyzed the corresponding results. DDVM and MA wrote the manuscript. DDVM, GR, GN, MS, Al, PL, RB, LM, Hl, PNS, and MA contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

del Valle-Morales, D., Romano, G., Nigita, G. et al. METTL3 alters capping enzyme expression and its activity on ribosomal proteins. Sci Rep 14, 27720 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78152-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78152-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic, ribosomal, and immune dysregulation in paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome

Molecular Psychiatry (2025)