Abstract

This study uses a 2D high-resolution thermo-mechanical coupled model to investigate the dynamic processes of deep plate hydration, dehydration, and subsequent magmatic activity in ocean-continent subduction zones. We reveal the pathways and temporal evolution of water transport to the deep mantle during the subduction process. Plate dehydration plays a critical role in triggering partial melting of the deep mantle and related magmatic activity. Our study shows significant differences in the volumes of melt produced at different depths, with dehydration reactions in deeper regions being weaker compared to shallower ones. It takes a longer time to reach the suitable P-T conditions for hydrous melting in the deep mantle. The results highlight the geophysical significance of water transport in deep subduction zones and its role in magmatic processes, particularly in the formation of magma chambers beneath continental plates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water (as hydrogen) plays an important role in the geodynamics of our planet, not only by enhancing diffusion and creep1,2, but also by lowering the melting temperature of the rocks/mantle (i.e., ‘flux melting’)3,4. Furthermore, water can increase electrical conductivity5, significantly affect the solid-state viscosity of the convective mantle and dynamics of ascending plumes6,7,8, and trigger deep seismicity9,10. Slab dehydration significantly contributes to melt generation in the hot portion of the mantle wedge3,4and even in relatively cool environments above a subducting slab by lowering the melting temperature of rocks6,11. There is convincing evidence supporting slab dehydration at shallow and intermediate-depths (deeper crust and uppermost mantle)12,13,14. In contrast, the possibility and process of deep slab dehydration (at depth>300 km) are still poorly understood. However, deep slab dehydration is considered one of the most important dynamic processes in subduction zones because it provides a plausible explanation for the development of upwelling hydrous plumes15and intra-continental volcanism16, even though dehydration at such depths remains questionable.

Recently, water transport and melting have been considered in numerical modeling17,18,19,20,21, geological/geophysical observations16,22and laboratory experiments23,24. These studies reveal the mechanisms of deep water transport in subduction zones and their critical impact on the global water cycle.For example, Cai et al. (2018) revealed the depth distribution of plate hydration and the low-velocity zone in the upper mantle through three-dimensional seismic imaging in the central Mariana Trench25.Fujie et al. (2018) used ocean-bottom seismometers and reflection seismic data to study the Japan and Kuril trenches, discovering that plate bending faults play a crucial role in the hydration process. In particular, in the Japan Trench, the presence of faults significantly facilitates mantle hydration26.Grevemeyer et al. (2018) used global ocean-bottom seismic data to construct a velocity-depth model of the oceanic crust, investigating the impact of serpentinization on seismic characteristics, thereby revealing the complexity of the hydration processes within subduction zones27.Hermann and Lakey (2011) emphasized the decomposition process of water-rich chlorite-rich rocks under high-pressure conditions, highlighting the crucial role of these hydrous minerals in transporting water into the deep mantle in cold subduction zones28.Gies et al. (2024) used thermodynamic models of global subduction zones to assess the role of magnesium silicates and phase A in deep dehydration, revealing the importance of phase A’s dehydration reactions in the global water cycle29.

Laboratory studies further support these findings. Maurice, through high-pressure and high-temperature experiments, investigated the stability of hydrated magnesium silicates in subduction zones and found that phase E and phase A exhibit significant differences under varying conditions30.Howe and Pawley (2019) conducted an in-depth study on the stability of talc and the 10-Å phase under high-pressure conditions, revealing the influence of solid solution on mineral stability31.

Slab dehydration in subduction zones involves the decomposition of several hydrous phases, which can occur through either continuous or discontinuous reactions23. These reactions are pressure and temperature sensitive, with amphibole exhibiting a negative dP/dTslope3,4,32,33,34.Faccenda (2014) grouped the water processes in the subduction zone into three categories:

-

1)

Hydration of dry oceanic lithosphere prior to subduction. In this stage, the oceanic slab stores water as seawater percolates down into the dry mafic and ultramafic rocks through faults and cracks, while magmatic activities contribute minor amounts to the water storage35,36,37.

-

2)

The hydrated slab subducting into the mantle. In recent decades, seismic tomography and receiver functions have provided strong evidence for the presence of the hydrated slab in the deep mantle22,38,39.

-

3)

Slab dehydration. The slab releases water by expelling pore fluid and loosely bound water (Physical dehydration) and by separating structurally bound water (Chemical dehydration) due to increasing pressure and temperature conditions during subduction40,41.

Shallow and intermediate-depth dehydration, which primarily releases pore fluids, has been evidenced by many geophysical observations, such as significantly lower electrical resistivity14, high Vp/Vsratios associated with mainshock and aftershock sequences13, or the presence of a double seismicity zone (DSZ) in the mantle12. Serpentine (13 wt% H2O), chlorite (13 wt% H2O), talc (4.8 wt% H2O), brucite (31 wt% H2O) and amphibole (2.1 wt% H2O) are the primary hydrous phases in H2O-saturated peridotite at shallow depths (approximately 50 km) and under low-pressure conditions (P<2 GPa)23. At the depth between 50 and 150 km (2 GPa< P<5 GPa), chlorite becomes the dominant hydrous phase after serpentine decomposes. For moderate or hot slab geotherms, the deeper crust and uppermost mantle dehydrate most of water between 500 and 800 ℃42. For cold slab geotherms, fluids can be transported to greater depths (150 km< depth<300 km). Serpentine transforms into phase A (12 wt% H2O) at P>5 GPa, while serpentine, chlorite and talc transform into phase Å (13 wt% H2O) at 5 GPa< P<7 GPa and 600 ℃< T<700 ℃27,29,43. Laboratory experiments24,44have shown that the crust dehydrates completely at around 300 km, while significant hydration occurs in the upper mantle at intermediate depths in hot and almost all cold subduction zones (except for the coldest ones, such as the western Pacific)41,45.

However, systematic research on deep dehydration processes (beyond 300 km) and their impact on the mantle remains limited. Although some scholars believe that under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, water is unlikely to penetrate deep into the mantle, increasing evidence suggests that subducting plates can transport water to depths exceeding 300 km. Furthermore, the release of deep water may trigger mantle melting and promote the upward migration of water, thereby influencing tectonic activity in subduction zones46,47. Stalder and Ulmer (2001) found that clinohumite (2.9 wt% H2O) can remain stable up to 1100 ℃ and 14 GPa48. This result implies that fluids can be transported down to transition zone (~ 440 km). Phase A and clinohumite transform into phase E (11.4 wt% H2O) at P >12 GPa, and as the pressure increases to 15–17 GPa, phase E transforms into superhydrous phase B (5.8 wt% H2O). The final phase of dense hydrous magnesium silicates (DHMS) is phase D (10–14 wt% H2O), which can remain stable down to 1200 km49. A series of solid-solid phase transformations in a cold slab geotherm, which can prevent slab dehydration, helps DHMS carry fluids down to the lower mantle43. Although DHMS has never been observed in nature and is unlikely to occur in the transition zone due to the high water solubility in wadsleyite and ringwoodite50, its presence makes it possible for fluids to be transported downward and/or released at depths greater than 300 km. There is still limited but growing evidence supporting slab dehydration at depths greater than 300 km12,16.

Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively examine the water migration process within subducting slabs throughout the entire subduction process using a numerical simulation model, with a particular focus on dynamic behavior in deeper regions.This study systematically investigates the dynamic process of deep dehydration in subducting slabs and its significant role in Earth’s deep processes using 2D high-resolution thermo-mechanical coupled oceanic-continental subduction models.We focus on dehydration events in subducting slabs at depths exceeding 300 km, as well as how the water released during these dehydration processes migrates within the mantle and influences partial mantle melting.

Through quantitative analysis, we estimated the amount of water released and its migration pathways under different geological conditions, and discussed the potential contribution of these dehydration events to magma activity and mantle plume formation.

Methods

Model setup

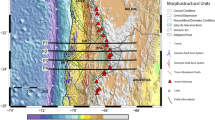

Our model represents a cross-section of an ocean-continent subduction zone (Fig. 1), extending from the bottom of the upper mantle to the lithosphere, with an area of 820 km in depth and 4000 km in horizontal length. The model is based on the 2D thermo-mechanical code (I2ELVIS)18,51, which operates using finite differences and the marker-in-cell method. The 2D coupled thermo-mechanical model simulates the forced subduction of an oceanic plate beneath a continental plate. The model is divided into non-uniform rectangular grids with 2041 × 481 nodes, containing more than 10 million randomly distributed markers. The subduction zone (from x = 1498 km to x = 3002 km) has a high resolution (1 km×1 km) in both horizontal and vertical directions, while the rest of the region adopts a relatively lower resolution, which varies horizontally from 1.0421 km to 5.0046 km depending on the distance from the subduction zone. The initial set of materials is shown in Fig. 1, and detailed material properties are listed in Tables 1 and 2. A wet, low brittle/plastic strength, rheological olivine weak shear zone, with sin(φ) = 0.1 (where φ is the effective internal friction angle), is established between the overriding and subducting slabs to initiate subduction. The accretionary sediments are situated between the oceanic and continental crust, and overlie the weak shear zone (Fig. 1).

(a) Initial model geometry and boundary conditions (see text Sect. 2.1 of the text for details). The arrows on both sides indicate the locations where an initial convergence rate is imposed. (b) Enlarged composition field map of the trench area enclosed by the bold black line in (a). Isotherms are displayed as white lines with increments of 200 ℃, starting from 100 ℃. A weak zone, characterized by wet olivine rheology and low plastic strength (low coefficient of internal friction), is imposed between the subducting and overriding plates. The accretionary sediments are situated between the oceanic and continental crust, overlying the weak shear zone. The material legend is used for all model snapshots in this paper: 1-air, 2-sea water, 3-upper sediments, 4-lower sediments, 5-upper continental crust (felsic), 6-lower continental crust (felsic), 7-upper oceanic crust (basalt), 8-lower continental crust (gabbro), 9-dry mantle lithosphere, 10-dry asthenosphere, 11-weak initial shear zone, 12-hydrated mantle, 13-serpentinized mantle, 14-molten asthenosphere, 15-re-molten mantle.The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

The bottom boundary of the model is open, while the other three boundaries are free-slip surfaces52,53. A boundary push (imposed on both the subducting and overriding plates) at a pre-existing weak zone initiates the subduction, until the oceanic slab sinks approximately 100–150 km into the mantle, at which point the subduction system can transition into a self-sustaining process. The initial thermal field in the subducting plate is set according to an oceanic geotherm54 corresponding to a 40 Ma lithospheric cooling age20. The initial temperature of the overriding continental plate linearly increases from 0 ℃ at the surface to 1367 ℃ at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary, below which an adiabatic temperature gradient of 0.5 ℃/km is applied.

In this study, we conducted a systematic sensitivity analysis by adjusting several key parameters (such as convergence rate, viscosity, etc.) one at a time, with other conditions held constant. Despite extensive comparative testing, this paper presents results selected from multiple simulations based on the depth of research and practical application considerations. The chosen scenario most closely reflects realistic geological processes and provides the most comprehensive depiction of the actual subduction processes of the Eurasian and Pacific plates.

Hydration and dehydration process

Our model initially sets a homogeneously hydrated oceanic crust with a thickness of 7 km, composed of 2 km of hydrothermally altered hydrated basalts (4 wt% H2O) and 5 km of gabbros (1.4 wt% H2O). These water contents represent fluids, which primarily originate from the slab hydration process at the mid-ocean ridge. In our model, the main shallow hydration process occurs at the slab bending zone. Prior to subduction, the oceanic plate begins to bend downward, placing the near-surface rocks under tension, which leads to the generation of normal faults. Fluids percolate deeply into the bending oceanic plate along these normal faults, facilitating the downward migration of fluids and further reactivation34 (Fig. 2). Another shallow hydration process of the oceanic plate occurs when seawater percolates into the porous and permeable basaltic crust. The maximum serpentinization depth at the trench is set to reach down to sub-Moho levels (10–20 km). A finite brittle deformation threshold (e.g. \(\varepsilon_{serp}\) =0.05 in our experiments) is set to control the extent of mantle serpentinization. When the deformation of the lithospheric mantle exceeds the prescribed threshold, the material transforms into serpentinized rock (2 wt% H2O) with 15% serpentinization (Fig. 2). The dataset for the initial maximum serpentinization is based on the average values estimated from tomographic studies at the trench36,64,65. At intermediate to deep depths, plastic behavior is not active. In our model, serpentinization of the slab interior occurs intrinsically, controlled by the reaction between excess fluids and the dry rocks through which they migrate.

Both porous compaction and dehydration reactions contribute to the expulsion of water from the subducting oceanic plate. Free fluids in hydrous basalts and gabbros gradually decrease from 4 wt% H2O/1.4 wt% H2O to zero at shallow depths (around75 km)66:

,

where \(\:{\text{X}}_{{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}}^{0}\) is the weight% of water at the surface, \(\:\varDelta\:\text{y}\)is the depth in km (0–75 km). We calculate the dehydration reactions/water release on the basis of physicochemical conditions and the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium20,66,67. The hydration and dehydration processes are modeled using markers. A dehydration curve is used to control the dehydration reaction, which is defined as23:

where T is the dehydration temperature in ℃, and Pis the current pressure in MPa. The released fluid is stored in a newly generated Lagrangian marker (referred to as a water marker) and propagates upward into the mantle wedge51,68. The migration velocity of the water marker is calculated as53:

where \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{x}}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{n}\text{t}\text{l}\text{e}}\) and \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{y}}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{n}\text{t}\text{l}\text{e}}\) are the local velocities of the mantle in x and y direction, respectively. \(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{y}}^{\text{p}\text{e}\text{r}\text{c}\text{o}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}}=10\:\text{c}\text{m}/\text{a}\)describes the relative velocity of the upward percolation of water. The water marker propagates upward independently until it encounters mantle rocks, which can consume the water through hydration reactions or partial melting. The seismic data69 suggest that most mantle wedges contain average water contents of less than ~ 4 wt%, while saturated mantle rocks can contain up to ~ 8 wt% H2O70. Based on this observation, we assume an incompletely hydrated mantle wedge with 2 wt% H2O as a result of the channelization of slab-derived fluids66,71,72.

Studies have shown that deep slab dehydration in subduction zones is influenced by both slab morphology and pressure-temperature (P-T) conditions. These conditions can lead to regions with high water content and may trigger mantle melting73,74. Based on these findings, water migration during hydration and dehydration processes is primarily controlled by P-T conditions (see Table 2) and water stability equilibrium (≤ 2 wt% H2O), and is calculated based on geophysical-chemical conditions and thermodynamic equilibrium assumptions20,66.In our model, Perple_X is embedded as a function to control water migration through P-T conditions70,75. For example, the P-T conditions for the water content in sediments are set to Pmax= 7 GPa and T = 1500 °C, as sediments typically do not subduct into deeper parts of the mantle. In contrast, the P-T conditions for the water content in oceanic crust and mantle material are set to 30 GPa to simulate water migration throughout the entire upper mantle and the upper part of the lower mantle, including the mantle transition zone (MTZ)76.

During the calculation, the water content of each rock type is determined by tracking the P-T changes at each time step, with water migration is achieved through Lagrangian water advection points. These water advection points migrate upward independently until they are depleted by hydration or partial melting processes (0 wt% H2O)51,53,77,78,79,80.The equations governing the melting process in the model take into account pressure, temperature, water content, and the melting properties of minerals63.

Snapshots of (a) the composition and (b) the viscosity fields of the reference model. White arrows in the viscosity snapshot represent velocities. Serpentinized faults are trenchward-dipping, but sets of antithetic and seaward-dipping faults are occasionally visible. The initial pore water in the basaltic layer is either pumped downward, leading to serpentinization, or expelled upward into the overlying mantle wedge and accretionary prism as the slab subducts. Fault activation due to the bending of the plate begins at shallow depths offshore of the trench and progressively deepens. The subducting slab becomes hydrated in the bending area as fluids percolate down into the dry mafic and ultramafic rocks through faults, cracks, or fluid infiltration. As the oceanic plate descends, the surrounding mantle begins to undergo flux melting. Decompression melting occurs beneath the back-arc extension zone.The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

Magma-related process

Similar to the aforementioned hydration and dehydration processes, our experiments use Lagrangian Markers to track magma-related processes during model evolution (i.e. partial melting, melt extraction, percolation and accretion). A simplified method81 is adopted to implement magma-related processes in our 2D coupled thermal-mechanical models.

Katz et al63. presented a parameterization for melt fraction as a function of pressure, temperature, water content, and modal cpx, based on recent thermodynamic and experimental investigations. This melt fraction is applied in our models as:

where \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}}\) is the degree of melting prior to the exhaustion of cpx, \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}}\) is the degree of melting for\(\:\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\), and after the exhaustion of cpx, the melting reaction primarily consumes opx. T is the temperature in Kelvin, \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\) and \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\) are the solidus and liquidus of the mantle, respectively (shown in Table 2). \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}^{\text{l}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{z}}\)(lherzolite liquidus) is used to create a kinked melting function63. \(\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}}={{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}}=1.5\)are the equation exponents derived from the “best fit” assemblage of the experimental solidus from Hirschmann60. \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\)=0.15/(0.5 + 0.08P) (where P is the pressure in GPa) represents the total degree of cpx melting degree in a closed (batch) system. \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}={\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}^{{{\upbeta\:}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}}^{-1}}\left({\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}^{\text{l}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{z}}-{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\right)+{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\) is the temperature (in Kelvin) when cpx is exhausted through isobaric melting.

Partial melting is observed over a wide area in our model, which is similar to the melt pooling region82. The melt is extracted and stored in the shallowest part of the partial melting zone, and this process is tracked by Lagrangian markers in our models. The melt transportation is implemented by converting the markers (representing molten mantle/asthenosphere) into a new marker type (molten basalt) in the shallowest part of the melting pool (The shallow region where melt migrates upward and accumulates during partial melting). The total amount of extracted melt corresponds to the volume of the converted markers. The melt amount for each marker is calculated at every modeling time step using the following equation:

where\(\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}\) is the standard melt fraction (\(\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}={\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\), \(\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}={\text{M}}_{\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\)), n indicates the number of previous extraction time steps, and \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\) represents the amount of extracted melt at the i-th time step. The rock is considered refractory/non-molten when the total extracted melt fraction (\(\:\sum\:_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{M}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}})\) is larger than the standard melt fraction (\(\:{\text{M}}_{0}\)). If the total amount of melt (\(\:\text{M}\)) exceeds a certain threshold, the melt in the marker is extracted, and \(\:\sum\:_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{M}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}}\)is updated. The extracted melt is transmitted instantaneously to the emplacement area (e.g. the shallowest part of the melting pool where it forms a magma chamber), as the extracted melt leaves the melting zone much faster than rock deforms83,84. It is assumed that 80% of the extracted melt is emplaced at lower depths or beneath the continental plate, forming plutons in the continental crust in areas of highest possible intrusion emplacement. The remaining 20% can propagate upwards to the surface above the extraction zone, influencing surface topography evolution (e.g. forming volcanoes). A high potential local crustal divergence rate is used to predict the location of extracted melt intrusion emplacement, which is determined by the ratio of effective melt overpressure to the effective viscosity of the crust66:

where \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{m}\text{e}\text{l}\text{t}}\) and \(\:\text{P}\) are the pressures at the extraction depth (\(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{m}\text{e}\text{l}\text{t}}\)) and the current depth (\(\:\text{y}\)), respectively, \(\:\text{g}\) is the gravitational acceleration, \(\:{\uprho\:}\) is the melt density, and \(\:{\upeta\:}\) is the current effective local crustal viscosity. Extracted melts are emplaced at the depth where the computed local crustal divergence rate is highest. To correctly couple the local and global flow field, the effects of matrix compaction in the melt extraction zone and crustal divergence in the melt emplacement area must be taken into account. We address these processes using a compressible continuity Eq. 68.

The effective values of other physical parameters of materials during magma-related processes are calculated using equations modified based on the melt fraction. The latent heating effect due to melting/crystallization equilibrium is accounted for by increasing the effective heat capacity and thermal expansion in the energy conservation equation:

where \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{e}\text{f}\text{f}}\) represents the effective value of a physical parameter, \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{m}\text{o}\text{l}\text{t}\text{e}\text{n}}\) and \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}}\) are the values of the physical parameter in the molten and solid phases, respectively. \(\:{\text{Q}}_{\text{L}}\)is the latent heat, and \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}/\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}}\) is the melt fraction (\(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}/\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}}={\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}},\) \(\:\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}/\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}}={\text{M}}_{\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\)). All material parameters are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Results

We investigate the dynamic processes of slab hydration and dehydration in an ocean-continent convergence subduction system using 2D high-resolution thermo-mechanical models51,68. Particular attention is given to the evolution of deep slab dehydration and the transport of partial melts from deep magmatism.

General model behavior

The general dynamic evolution of our reference model is shown in Fig. 3. In the earliest stage (Fig. 3a), the subducting slab becomes hydrated in the bending area, where seawater percolates down into dry mafic and ultramafic rocks through faults, cracks or fluid infiltration. As the oceanic plate descends, the surrounding mantle begins to melt due to the release of fluids from the hydrated surface of the subducting slab, which lowers the mantle solidus. Above the hydrated and partially molten mantle, a magmatic arc forms at the surface of the continental plate. The partially molten mantle rises upward, accompanied by the extension of the mantle lithosphere, leading to the formation of new volcanic crust at the surface. The hydrated slab is carried into the deep mantle by subduction.

The general evolution of the reference model is illustrated by composition. The left inset figures in each snapshot are enlarged composition field maps, enclosed by bold black lines. (a) In the early stage of subduction, the oceanic slab becomes hydrated at the trench, and the hydrated slab is then transported into the deep mantle by subduction. (b) The stagnant slab transports fluids to deep regions far from the trench. These fluids are released and hydrate the surrounding mantle, leading to the generation of deep partial melts. At the surface, decompression melts and flux melts are extracted and emplaced beneath the back-arc extension zone, resulting in the formation of new back-arc basin basalts. (c) The stagnant slab is warmed by the surrounding hot mantle, inducing more water release and consequently generating more deep partial melts. d) The progressive deep dehydration of the stagnant slab induces more partial melting and upwelling of wet peridotite. The plumes generated by magmatism induced by deep slab dehydration are emplaced and form magma chambers beneath distant parts of the continental plate.The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

The subducting slab reaches the 660 km transition zone, causing it to bend. The stagnant slab continues moving forward, transporting fluids to deep regions far from the trench (Fig. 3b). The deep portion of the subducting slab begins to release fluids, which hydrate the surrounding mantle and generate partial melts in the deep region. Some plumes resulting from deep slab dehydration rise upward. The migration path of these upwelling plumes is influenced by mantle convection. Furthermore, the decompression melts and flux melts are extracted and emplaced beneath the back-arc extension zone, leading to the formation of MORB-like back-arc basin basalts (BABB).

Subduction slows down due to a decrease in driving force and an increase in resisting force. The stagnant slab is warmed by the surrounding hot mantle. As a result, more water is released from the heated slab, leading to the generation of more deep partial melts. These deep partial melts coalesce into a mass and begin to upwell (Fig. 3c).

After a pause of several million years (e.g. 10 Ma), the oceanic plate resumes subducting. The trench begins to retreat again, and a new back-arc extension zone is formed. The episodicity of subduction has been observed in many subduction zones, such as the central Mediterranean region85, the Parece-Vela Basin, and the Mariana Trough86. During this period, the deep part of the subducting slab becomes hotter, generating more partial melts. The plumes generated by deep slab dehydration-induced magmatism are emplaced and form magma chambers beneath distant parts of the continental plate (Fig. 3d).

Water transport

Initially, the subducting slab becomes hydrated at the trench and carries more than 1 wt% H2O into the mantle (Fig. 4a). The fluids carried by the slab are gradually consumed by dehydration as subduction continues. These fluids are not fully exhausted at shallow and intermediate depths but are instead carried into the deep mantle by the subducting slab. A series of solid-solid phase transformations in a cold slab geotherm involving DHMS can prevent slab dehydration and help carry fluids down to the lower mantle43. Approximately 0.4–0.8 wt% H2O can be transported to the ~ 660 km transition zone (Fig. 4a). The stagnant slab, warmed by the surrounding hot mantle, releases additional fluids, which in turn hydrate the mantle above the slab. The hydrated mantle contains approximately 0.4–0.6 wt% H2O, and in some regions, the fluid content can reach up to ~ 0.9 wt% H2O (Fig. 4b). In some areas of the stagnant slab, where the released fluids cannot be completely consumed by hydration reactions or partial melting, the remaining fluids penetrate upward and hydrate the mantle wedge above the slab (Fig. 4c). If the volume of these fluids is sufficient, they can even transport 0.4–0.5 wt% H2O upward to the bottom of the continental plate without being exhausted (Fig. 4d). In the later stages of subduction (e.g. 95.4 Ma, Fig. 4d), some parts of the stagnant slab have mostly completed the dehydration process and retain only 0.2–0.3 wt% H2O. Notably, numerical modeling by Yang and Faccenda (2020) indicates that when water content in the mantle transition zone reaches 0.2-0.3%, localized melting and magmatic activity may be triggered, which is consistent with the observations in this study regarding the potential for deep dehydration to induce magmatic activity87.

The temporal evolution of the hydrated mantle volume (Fig. 5) shows that shortly after subduction initiation (<5 Ma), the mantle is hydrated by the sinking slab at shallow and intermediate depths (Fig. 4a). Around 10 Ma, the subducting slab bends at the ~ 660 km transition zone. As subduction continues, the stagnant slab progresses forward, leading to more of the slab lying on the transition zone and more deep mantle (>300 km) being hydrated by fluids released from the slab. The total volume of hydrated mantle primarily comes from the deep-depths hydrated mantle. Between 30 and 90 Ma, subduction slows down, and deep dehydration enters a stable period (Fig. 4b and c). After ~ 90 Ma, deep dehydration becomes active again as the surrounding hot mantle warms the slab sufficiently, leading to episodic subduction (Fig. 5). During this period, the majority of fluids in the stagnant slab are consumed by dehydration and partial melting (Fig. 4d).

Volumes of hydrated mantle within a 0-140 Ma window for the reference model are measured in km3/km. Except for the initial period (<5 Ma), the total volume of hydrated mantle primarily comes from the deep-depths hydrated mantle.The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

P-T conditions and deep magmatism

The onset of mantle partial melting is controlled by its solidus curve, which is significantly influenced by the bulk water content. The solidus of the deep mantle can decrease by more than 1000 ℃ when the mantle transitions from dry to containing 0.2 wt% bulk water (Fig. 6). The melt fraction (M0) also influences the solidus of the mantle, though not significantly. The solidus of the mantle changes very little (no more than 100 ℃) when the melt fraction varies from 0 to 0.6 under the same hydrous conditions (Fig. 6). During subduction, the pressure field remains almost unchanged, while the temperature field varies by several hundred degrees Celsius in the deep mantle (Fig. 7). The temperature of the deep mantle decreases as heat is transferred to the subducting slab. This heat transfer warms the slab, causing it to release more fluid. The progressively increasing water released from the slab propagates upward into the surrounding mantle, lowering its solidus. The decrease in the solidus is much greater than the change in temperature. This is due to the increased partial melting in the deep mantle.

The temporal evolution of partial melt volume (Fig. 8) indicates that the generation of a large amount of partial melts in the deep mantle requires a long period of time. This time allows for sufficient water to be released from the subducting plate, ensuring that the solidus of the mantle is lowered to a sufficiently low level due to the increasing fluid content. Prior to this period, shallow and intermediate-depth partial melting dominates the total magma production. Thereafter, deep partial melting contributes increasingly to the total magma production (Fig. 8).

Solidus of peridotite in our models.\(\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}\) represents the melt fraction (\(\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}={\text{M}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{s}\text{o}\text{l}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}\) ,\(\:\:{\:\text{M}}_{0}={\text{M}}_{\text{o}\text{p}\text{x}},\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{n}\:{\text{T}}_{\text{c}\text{p}\text{x}-\text{o}\text{u}\text{t}}<\text{T}<{\text{T}}_{\text{l}\text{i}\text{q}\text{u}\text{i}\text{d}\text{u}\text{s}}\)). The solidus decreases as the bulk water content varies from 0 to 0.2 wt%. The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

The volumes of partial melt within a 0-140 Ma window for the reference model are measured in km3/km. The majority of deep-depth partial melt is generated during the later stages of subduction (>90 Ma).The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

Discussion

Detached slab deep dehydration

Slab detachments are frequently observed in subduction zones88,89. The detached slab lying on the ~ 660 km transition zone can also release fluids and trigger deep mantle partial melting under specific P-T conditions. These hydrous upwellings from the lower mantle, resulting from residual detached slab dehydration, can even trigger new subduction zones by hydrating the overriding lithosphere and developing a low-viscosity, dipping shear zone within it15. Our models simulate slab break-off from the surface down to the ~ 660 km transition zone. Various slab detachment depths have been proposed by several previous studies90,91,92,93,94. The timing of slab detachment varies from the very early stages of subduction (<10 Ma) to the later stages (>50 Ma). The age of the subducting slab is positively correlated with the time of slab detachment, meaning that the older the slab, the longer the detachment time. This relationship is due to the increase in slab thermal thickness, which prolongs the thermal relaxation time and thus delays the necking process93,95. Additionally, early detachment tends to occur at shallower depths. Slab detachment is a highly complex process governed by numerous parameters. In our experiments, not all later detachments occur at greater depths (Fig. 9d).

Figure 9 illustrates the deep dehydration of residual detached slabs in four models, each with different detachment depths and times. Shallow detachment (<300 km) causes the subducting slab to suddenly sink into the deep mantle. The upper portion of the subducting slab does not have enough time to dehydrate at shallow and intermediate depths before suddenly sinking. Consequently, more fluids are transported to the deep mantle along with the suddenly sinking upper portion of the detached subducting slab. This portion can release more fluids than others because it contains more water (Fig. 9a and d). The falling portions of intermediate and deep detachment (300–660 km) exhibit a similar volume distribution of slab dehydration as the models without slab detachment (Fig. 9b and c). Since the falling portions of intermediate and deep detachment have sufficient time for dehydration, the volume of water carried into the deep mantle by these falling portions does not change significantly. The duration of the slab detachment process is also a critical parameter that controls how much water can be carried into the deep mantle by the upper portion of the detached subducting slab. However, the duration of the slab detachment process is highly complex, as it is governed by numerous parameters. A systematic study of this topic is beyond the scope of this paper.

Dehydration and solidus curves

In our models, the dehydration reaction is controlled using a dehydration curve proposed by Schmidt and Poli (SP1998)23. Faccenda et al21. suggested that a partially hydrated layer, where fluid concentration forms in the lithospheric mantle, develops more readily and at shallower depths (within the 450 ± 50 ℃ temperature range) using the dehydration curve proposed by Wunder and Schreyer96(WS1997) compared to SP1998. However, Faccenda et al21. suggested that under high confining pressures, the WS1997 dehydration curve has a very small and negative slope compared to SP1998. This is because the thickness of the Dehydration-Driven Zone (DHZ) is sensitive to the slab’s thermal structure rather than to the maximum temperature at which antigorite remains stable.

The solidus curve used in our models was proposed by Katz et al63., who provided a parameterization for melt fraction as a function of pressure, temperature, water content, and modal clinopyroxene (cpx), based on data from recent thermodynamic modeling and experimental studies. The parameterization represents a simplification of the complex natural system. For simplicity, it does not take into account factors such as the exhaustion of aluminous phases, the loss of orthopyroxene (opx) from the residue, and compositional variability. The solidus curve by Katz et al63. is applicable up to a maximum pressure of about 8 GPa (~ 250 km), while we have linearly extrapolated the curve to 24 GPa (~ 750 km). To enhance accuracy, the solidus curve should be refined using additional data from high-pressure and high-temperature experimental studies on peridotite melting and hydrous equilibria. If the solidus curve is refined, we can expect simulation results that are closer to natural systems.

Color snapshots illustrate the dehydration of residual detached slabs in the deep mantle. (a) Slab breaks off at shallow depths during the early stage of subduction (<10 Ma). (b) Slab breaks off at intermediate depths (~ 300 km). (c) Slab breaks off at deep depths (~ 660 km). (d) Slab breaks off at shallow depths during the later stage of subduction (>50 Ma).The map was generated using MATLAB (R2022a, MathWorks, https://www.mathworks.com).

Evidences for deep slab dehydration

There is limited and indirect evidence supporting dehydration at depths greater than 300 km, but there is gradually increasing evidence supporting slab dehydration at such depths. Recently, a diamond containing ~ 1.5 wt% H2O in hydrous ringwoodite provided evidence that, at least locally, the mantle transition zone may be close to water saturation97.Consistent with the findings of Cerpa et al98. suggesting that only the coldest slabs can transport water into the mantle transition zone, our results also indicate that the deep dehydration process is relatively slow but can lead to large-scale mantle melting. Schmandt et al99. suggested that producing up to 1% melt through the dehydration melting of hydrous ringwoodite, which is viscously entrained into the lower mantle, is feasible. This conclusion is supported by evidence indicating that partial melting near the ~ 410 km discontinuity in a bulk peridotite system with 1 wt% H2O could result in approximately 5% partial melt at this depth100,101. At this depth, the partition coefficient of H2O between wadsleyite and olivine is at least 5:1102. Recent experiments have suggested that the partition coefficient of H2O between ringwoodite and silicate perovskite at the 660 km transition zone is as high as 15:1102. In our experiments, we observed deep slab dehydration and associated magmatism. This regime has been proposed to explain the origin of far-field intercontinental volcanism and magmatism in East Asia16,21,34,103,104,105. Van Der Lee et al15. suggested that deep slab dehydration could trigger subduction initiation along a passive margin. High Q−1 and low-velocity anomalies above the stagnating Pacific slab beneath East Asia may be caused by the dehydration of DHMS phases or the diffusion of water from an H2O-undersaturated slab at the 660 km transition zone104.

Conclusion

Our experiments reveal the complete dynamic process of deep slab dehydration and magmatism, and demonstrate the possibility of slab dehydration at the 660 km transition zone. The volume of partial melts produced by slab dehydration at shallow to intermediate depths (<300 km) is approximately 2.5 times greater than that produced by deep slab dehydration (>300 km) at around 95 Ma (Fig. 8). In contrast, the volume of hydrated mantle at deep depths is three times greater than that at shallow to intermediate depths (Fig. 5). This implies that the dehydration reactions in the deep region is relatively weaker than in the shallow region. Generating significant dehydration-induced partial melts at deep depths requires a long period, as it takes time to achieve the appropriate P-T conditions for hydrous melting in the deep mantle. The progressively increasing amount of water released from the slab propagates upward into the surrounding mantle, lowering its solidus. This contributes to the increased amount of partial melting in the deep mantle. Plumes resulting from deep dehydration-induced magmatism can upwell and form magma chambers beneath far-field intercontinental plates.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

09 January 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84095-8

References

Kohlstedt, S. M. L. Influence of water on plastic deformation of olivine aggregates: 1. Diffusion creep regime %J. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 105, 21457–21469. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jb900179 (2000).

Mei, S. & Kohlstedt, D. L. Influence of water on plastic deformation of olivine aggregates 2. Dislocation creep regime. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 105, 21471–21481. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jb900180 (2000).

Peacock, S. A. Fluid processes in subduction zones. %J Science (New York, N.Y.). Vol.248, 329–337, doi: (1990). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.248.4953.329

Peacock, S. M. Numerical simulation of metamorphic pressure-temperature‐time paths and fluid production in subducting slabs %J tectonics. 9, 1197–1211, doi: (1990). https://doi.org/10.1029/TC009i005p01197

Wang, D. J., Mookherjee, M., Xu, Y. S. & Karato, S. The effect of water on the electrical conductivity of olivine. Nature. 443, 977–980. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05256 (2006).

Ohtani, E., Litasov, K., Hosoya, T., Kubo, T. & Kondo, T. Water transport into the deep mantle and formation of a hydrous transition zone. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 143–144, 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2003.09.015 (2004).

Gerya, T. Future directions in subduction modeling. J. Geodyn. 52, 344–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2011.06.005 (2011).

Zhu, G., Gerya, T. V., Honda, S., Tackley, P. J. & Yuen, D. A. Influences of the buoyancy of partially molten rock on 3-D plume patterns and melt productivity above retreating slabs. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 185, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2011.02.005 (2011).

Karato, S., Riedel, M. R. & Yuen, D. A. Rheological structure and deformation of subducted slabs in the mantle transition zone: implications for mantle circulation and deep earthquakes. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 127 (01), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9201(01)00223-0 (2001).

Kelemen, P. B. & Hirth, G. A periodic shear-heating mechanism for intermediate-depth earthquakes in the mantle. Nature. 446, 787–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05717 (2007).

Bercovici, D. & Karato, S. Whole-mantle convection and the transition-zone water filter. Nature. 425, 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01918 (2003).

Brudzinski, M. R., Thurber, C. H., Hacker, B. R. & Engdahl, E. R. Global prevalence of double benioff zones(article. %J Sci. 316, 1472–1474. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1139204 (2007).

Nakajima, J., Hasegawa, A. & Kita, S. Seismic evidence for reactivation of a buried hydrated fault in the Pacific slab by the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gl048432 (2011).

Worzewski, T., Jegen, M., Kopp, H., Brasse, H. & Castillo, W. T. Magnetotelluric image of the fluid cycle in the Costa Rican subduction zone. Nat. Geosci. 4, 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1041 (2011).

van der Lee, S., Regenauer-Lieb, K. & Yuen, D. A. The role of water in connecting past and future episodes of subduction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 273, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.04.041 (2008).

Zhao, D. & Ohtani, E. Deep slab subduction and dehydration and their geodynamic consequences: evidence from seismology and mineral physics. Gondwana Res. 16, 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2009.01.005 (2009).

Arcay, D., Tric, E. & Doin, M. P. Numerical simulations of subduction zones: Effect of slab dehydration on the mantle wedge dynamics. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 149, 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2004.08.020 (2005).

Gerya, T. V., Connolly, J. A. D. & Yuen, D. A. Why is terrestrial subduction one-sided? Geology 36, 43–46, doi: (2008). https://doi.org/10.1130/g24060a.1

Faccenda, M., Gerya, T. V. & Burlini, L. Deep slab hydration induced by bending-related variations in tectonic pressure. Nat. Geosci. 2, 790–793. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo656 (2009).

Gerya, T. V. & Meilick, F. I. Geodynamic regimes of subduction under an active margin: effects of rheological weakening by fluids and melts. J. Metamorph. Geol. 29, 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2010.00904.x (2011).

Faccenda, M., Gerya, T. V., Mancktelow, N. S. & Moresi, L. Fluid flow during slab unbending and dehydration: implications for intermediate-depth seismicity, slab weakening and deep water recycling. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gc003860 (2012).

Rondenay, S., Abers, G. A. & Van Keken, P. E. Seismic imaging of subduction zone metamorphism. Geology. 36, 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1130/g24112a.1 (2008).

Schmidt, M. W. & Poli, S. Experimentally based water budgets for dehydrating slabs and consequences for arc magma generation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 163, 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-821x(98)00142-3 (1998).

Okamoto, K. & Maruyama, S. The eclogite–garnetite transformation in the MORB + H2O system. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 146, 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2003.07.029 (2004).

Chen Cai, D. A. W., Shen, W. & Shen, W. Melody Eimer Water input into the Mariana subduction zone estimated from ocean-bottom seismic data %J nature. 563, 389–392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0655-4 (2018).

Fujie, G. et al. Controlling factor of incoming plate hydration at the north-western Pacific margin %J. Nat. Commun. 9 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06320-z (2018).

Grevemeyer, I., Ranero, C. R. & Ivandic, M. Structure of oceanic crust and serpentinization at subduction trenches. Geosphere 14, 395–418. https://doi.org/10.1130/ges01537.1 (2018).

Hermann, J. & Lakey, S. Water transfer to the deep mantle through hydrous, Al-rich silicates in subduction zones %J geology. 49, 911–915, doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1130/g48658.1

Gies, N. B., Konrad-Schmolke, M. & Hermann, J. Modeling the Global Water Cycle—the effect of Mg-Sursassite and phase A on Deep Slab Dehydration and the Global Subduction Zone Water Budget. 25, e2024GC011507, doi: (2024). https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GC011507

Maurice, J. et al. The stability of hydrous phases beyond antigorite breakdown for a magnetite-bearing natural serpentinite between 6.5 and 11 GPa. (; 1 LMV - Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, (2018).

Howe, H. & Pawley, A. R. The effect of solid solution on the stability of talc and 10-Å phase. %J Contrib. Mineralogy Petrol. 174 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-019-1616-0 (2019).

Peacock, S. M., THE IMPORTANCE OF BLUESCHIST - ECLOGITE & DEHYDRATION REACTIONS IN SUBDUCTING OCEANIC-CRUST. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 105, 684–694, (1993). doi:10.1130/0016–7606(1993)105<0684:Tiobed>2.3.Co;2

Peacock, S. M. Thermal and petrologic structure of subduction zones %J Geophysical Monograph Series. 96, 119–133, doi: (1996). https://doi.org/10.1029/GM096p0119

Faccenda, M. Water in the slab: a trilogy. Tectonophysics. 614, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2013.12.020 (2014).

Peacock, S. M. Large-scale hydration of the lithosphere above subducting slabs. Chem. Geol. 108, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2541(93)90317-c (1993).

Contreras-Reyes, E. et al. Deep seismic structure of the Tonga subduction zone: implications for mantle hydration, tectonic erosion, and arc magmatism. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 116 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jb008434 (2011).

Parai, R. & Mukhopadhyay, S. How large is the subducted water flux? New constraints on mantle regassing rates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317–318, 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.11.024 (2012).

Martin, S., Rietbrock, A., Haberland, C. & Asch, G. Guided waves propagating in subducted oceanic crust. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 108 https://doi.org/10.1029/2003jb002450 (2003).

Tsuji, Y., Nakajima, J. & Hasegawa, A. Tomographic evidence for hydrated oceanic crust of the Pacific slab beneath northeastern Japan: implications for water transportation in subduction zones. 35. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL034461 (2008).

Hyndman, R. D. & Peacock, S. M. Serpentinization of the forearc mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 212, 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-821x(03)00263-2 (2003).

van Keken, P. E., Hacker, B. R., Syracuse, E. M. & Abers, G. A. Subduction factory: 4. Depth-dependent flux of H < sub > 2 O from subducting slabs worldwide. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 116 https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jb007922 (2011).

Hacker, B. R., Abers, G. A. & Peacock, S. M. Subduction factory -: 1.: theoretical mineralogy, densities, seismic wave speeds, and H < sub > 2 O contents -: art. 2029. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 108 https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jb001127 (2003).

Fumagalli, P., Stixrude, L., Poli, S. & Snyder, D. The 10Å phase: a high-pressure expandable sheet silicate stable during subduction of hydrated lithosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 186, 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-821x(01)00238-2 (2001).

Litasov, K. D. & Ohtani, E. Effect of water on the phase relations in Earth’s mantle and deep water cycle %J Special Paper 421: Advances in High-Pressure Mineralogy. 421, 115–156, doi: (2007). https://doi.org/10.1130/2007.2421(08).

Iwamori, H. Phase relations of peridotites under H2O-saturated conditions and ability of subducting plates for transportation of H2O. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 227, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.08.013 (2004).

Wilson, C. R., Spiegelman, M., van Keken, P. E. & Hacker, B. R. Fluid flow in subduction zones: the role of solid rheology and compaction pressure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 401, 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.052 (2014).

Shirey, S. B., Wagner, L. S., Walter, M. J., Pearson, D. G. & van Keken, P. E. Slab Transport of Fluids to Deep Focus Earthquake Depths-Thermal Modeling Constraints and evidence from diamonds. Agu Adv. 2 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020av000304 (2021).

Stalder, R. & Ulmer, P. Phase relations of a serpentine composition between 5 and 14 GPa: significance of clinohumite and phase E as water carriers into the transition zone. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 140, 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004100000208 (2001).

Ohtani, E. Water in the mantle. Elements. 1, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.1.1.25 (2005).

Angel, R. J., Frost, D. J., Ross, N. L. & Hemley, R. Stabilities and equations of state of dense hydrous magnesium silicates. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 127 (01), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9201(01)00227-8 (2001).

Gerya, T. V. & Yuen, D. A. Characteristics-based marker-in-cell method with conservative finite-differences schemes for modeling geological flows with strongly variable transport properties. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 140, 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2003.09.006 (2003).

Gorczyk, W., Gerya, T. V., Connolly, J. A. D. & Yuen, D. A. Growth and mixing dynamics of mantle wedge plumes. Geology. 35, 587–590. https://doi.org/10.1130/g23485a.1 (2007).

Gorczyk, W., Willner, A. P., Gerya, T. V., Connolly, J. A. D. & Burg, J. P. Physical controls of magmatic productivity at Pacific-type convergent margins: Numerical modelling. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 163, 209–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2007.05.010 (2007).

DonaldL.Turcotte & JerrySchubert Geodyn. 136–136 (2003).

Bittner, D. & Schmeling, H. Numerical modelling of melting processes and induced diapirism In the lower crustGeophys. J. Int. 123, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.1995.tb06661.x (1995).

Ranalli, G. Rheology of the earth.

Clauser, C. & Huenges, E. Thermal Conductivity of Rocks and Minerals %J Rock Physics & Phase Relations: A Handbook of Physical Constants, Volume 3. 105–126 (1995).

Hofmeister, A. M. Mantle values of thermal conductivity and the geotherm from phonon lifetimes. Science. 283, 1699–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5408.1699 (1999).

Hess, P. C. Origins of igneous rocks. (1989).

Hirschmann, M. M. Mantle solidus: experimental constraints and the effects of peridotite composition %J G-Cubed: Geochemistry, Geophysics. Geosystems: Electron. J. Earth Sci. 1 https://doi.org/10.1029/2000gc000070 (2000).

Johannes, W. The significance of experimental studies for the formation of migmatites %J migmatites. 36–85, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1 (1985). -4613–2347–1_2.

Poli, S. & Schmidt, M. W. Petrology of subducted slabs. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 30, 207–235. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.30.091201.140550 (2002).

Katz, R. F., Spiegelman, M. & Langmuir, C. H. A new parameterization of hydrous mantle melting. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4 https://doi.org/10.1029/2002gc000433 (2003).

Ivandic, M., Grevemeyer, I., Bialas, J. & Petersen, C. J. Serpentinization in the trench-outer rise region offshore of Nicaragua: constraints from seismic refraction and wide-angle data. Geophys. J. Int. 180, 1253–1264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04474.x (2010).

Van Avendonk, H. J. A., Holbrook, W. S., Lizarralde, D. & Denyer, P. Structure and serpentinization of the subducting Cocos plate offshore Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 12 https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gc003592 (2011).

Vogt, K., Gerya, T. V. & Castro, A. Crustal growth at active continental margins: Numerical modeling. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 192–193, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2011.12.003 (2012).

Nikolaeva, K., Gerya, T. V. & Marques, F. O. Subduction initiation at passive margins: Numerical modeling. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 115 https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jb006549 (2010).

Gerya, T. V. & Yuen, D. A. Robust characteristics method for modelling multiphase visco-elasto-plastic thermo-mechanical problems. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 163, 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2007.04.015 (2007).

Carlson, R. L. & Miller, D. J. Mantle wedge water contents estimated from seismic velocities in partially serpentinized peridotites. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30 https://doi.org/10.1029/2002gl016600 (2003).

Connolly, J. A. D. Computation of phase equilibria by linear programming: a tool for geodynamic modeling and its application to subduction zone decarbonation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236, 524–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.033 (2005).

Davies, J. H. The role of hydraulic fractures and intermediate-depth earthquakes in generating subduction-zone magmatism %J nature. 398, 142–145, doi: (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/18202

Nikolaeva, K., Gerya, T. V. & Connolly, J. A. D. Numerical modelling of crustal growth in intraoceanic volcanic arcs. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 171, 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2008.06.026 (2008).

Hebert, L. B. & Montési, L. G. J. Hydration adjacent to a deeply subducting slab: the roles of nominally anhydrous minerals and migrating fluids(article) %J. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 118, 5753–5770. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jb010497 (2013).

Magni, V., Bouilhol, P. & van Hunen, J. Deep water recycling through time %J. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. Vol. 15, 4203–4216. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014gc005525 (2014).

Connolly, J. A. D. The geodynamic equation of state: what and how %J G-Cubed: Geochemistry, Geophysics. Geosystems: Electron. J. Earth Sci. 10, Q10014. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gc002540 (2009).

Li, Z. H., Gerya, T. & Connolly, J. A. D. Variability of subducting slab morphologies in the mantle transition zone: insight from petrological-thermomechanical modeling. %J Earth Sci. Reviews. 196, 102874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.05.018 (2019).

Sheng, J. et al. Influence of the Pacific plate subduction on the Tianchi volcano %J. Chin. J. Geophys. 61, 4396–4405. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2018L0309 (2018).

Wang, Z., Kusky, T. & Capitanio, F. Water transportation ability of flat-lying slabs in the mantle transition zone and implications for craton destruction %J tectonophysics. 723, 95–106, doi: (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2017.11.041

Sheng, J. et al. Dynamics of back-arc extension controlled by subducting slab retreat: insights from 2D thermo‐mechanical modelling. %J Geol. J. Vol. 54, 3376–3388. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.3336 (2019).

Steven, B. et al. Slab Transport of Fluids to Deep Focus Earthquake Depths—Thermal Modeling Constraints and Evidence From Diamonds %J AGU Advances. Vol.2, 10, doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020av000304

Gerya, T. V. Three-dimensional thermomechanical modeling of oceanic spreading initiation and evolution. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 214, 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2012.10.007 (2013).

Gregg, P. M., Behn, M. D., Lin, J. & Grove, T. L. Melt generation, crystallization, and extraction beneath segmented oceanic transform faults. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 114 https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jb006100 (2009).

Elliott, T., Plank, T., Zindler, A., White, W. & Bourdon, B. Element transport from slab to volcanic front at the Mariana arc. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 102, 14991–15019. https://doi.org/10.1029/97jb00788 (1997).

Hawkesworth, C. J., Turner, S. P., McDermott, F., Peate, D. W. & vanCalsteren, P. U-Th isotopes in arc magmas: implications for element transfer from the subducted crust. Science. 276, 551–555. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.276.5312.551 (1997).

Faccenna, C., Funiciello, F., Giardini, D. & Lucente, P. Episodic back-arc extension during restricted mantle convection in the Central Mediterranean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 187, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-821x(01)00280-1 (2001).

Funiciello, F., Faccenna, C., Giardini, D. & Regenauer-Lieb, K. Dynamics of retreating slabs: 2. Insights from three-dimensional laboratory experiments. J. Geophys. Research-Solid Earth. 108 https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jb000896 (2003).

Jianfeng Yang, M. F. Intraplate Volcanism Originating From Upwelling Hydrous Mantle Transition Zone%J Nature. 579, 88–91, doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2045-y

Wortel, M. J. R. & Spakman, W. Geophysics - Subduction and slab detachment in the Mediterranean-Carpathian region. Science. 290, 1910–1917. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5498.1910 (2000).

Wang-Ping, C. Evidence for a large-scale remnant of subducted lithosphere beneath Fiji. Science. 292, 2475–2479. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.292.5526.2475 (2001).

van de Zedde, D. M. A. & Wortel, M. J. R. Shallow slab detachment as a transient source of heat at midlithospheric depths. Tectonics. 20, 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001tc900018 (2001).

Gerya, T. V., Yuen, D. A. & Maresch, W. V. Thermomechanical modelling of slab detachment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 226, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2004.07.022 (2004).

Andrews, E. R. & Billen, M. I. Rheologic controls on the dynamics of slab detachment. Tectonophysics. 464, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2007.09.004 (2009).

Baumann, C., Gerya, T. V. & Connolly, J. A. D. Numerical modelling of spontaneous slab breakoff dynamics during continental collision %J Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Vol.332, 99–114, doi: (2010). https://doi.org/10.1144/sp332.7

Duretz, T. & Gerya, T. V. Slab detachment during continental collision: influence of crustal rheology and interaction with lithospheric delamination. Tectonophysics. 602, 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2012.12.024 (2013).

Duretz, T., Gerya, T. V. & May, D. A. Numerical modelling of spontaneous slab breakoff and subsequent topographic response. Tectonophysics. 502, 244–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2010.05.024 (2011).

Wunder, B., Schreyer, W. & Antigorite High-pressure stability in the system MgO–SiO2–H2O (MSH). Lithos. 41 (97), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0024-4937(97)82013-0 (1997).

Pearson, D. G. et al. Hydrous mantle transition zone indicated by ringwoodite included within diamond. Nature. 507, 221–. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13080 (2014).

Cerpa, N. G., Arcay, D. & Padrón-Navarta, J. A. Sea-level stability over geological time owing to limited deep subduction of hydrated mantle %J. Nat. Geoscience Vol. 15, 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-00924–3 (2022).

Schmandt, B., Jacobsen, S. D., Becker, T. W., Liu, Z. & Dueker, K. G. Earth’s interior. Dehydration melting at the top of the lower mantle. %J Sci. 344, 1265–1268 (2014).

Hirschmann, M. M., Tenner, T., Aubaud, C. & Withers, A. C. Dehydration melting of nominally anhydrous mantle: the primacy of partitioning. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 176, 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2009.04.001 (2009).

Tenner, T. J., Hirschmann, M. M., Withers, A. C. & Ardia, P. H2O storage capacity of olivine and low-Ca pyroxene from 10 to 13 GPa: consequences for dehydration melting above the transition zone. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 163, 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-011-0675-7 (2012).

Inoue, T., Wada, T., Sasaki, R. & Yurimoto, H. Water partitioning in the Earth’s mantle. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 183, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2010.08.003 (2010).

Richard, G., Bercovici, D. & Karato, S. I. Slab dehydration in the Earth’s mantle transition zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 251, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2006.09.006 (2006).

Richard, G. C. & Iwamori, H. Stagnant slab, wet plumes and cenozoic volcanism in East Asia. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 183, 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2010.02.009 (2010).

Zhao, D. P. & Tian, Y. Changbai intraplate volcanism and deep earthquakes in East Asia: a possible link? Geophys. J. Int. 195, 706–724. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggt289 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41404071) and China Scholarship Council (201304190035). All models in this paper are calculated on the Brutus Cluster, ETH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the study. H.W. was responsible for conceptualization, investigation, data curation, and writing the original draft. J.L. and Z.J. handled conceptualization, methodology, and review and editing of the manuscript. J.S., Y.Z., and J.W. were involved in writing the original draft, review and editing of the manuscript, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Affiliation. Affiliation 1 was incorrectly given as ‘College of Transportation Science & Engineering, Nanjing Technology University, Zhongshan North Road 200, Nanjing, 180009, China’. The correct affiliation is: ‘College of Transportation Engineering of Nanjing Tech, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing 211816, China.’

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Lei, J., Jia , Z. et al. Numerical modeling the process of deep slab dehydration and magmatism. Sci Rep 14, 26684 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78193-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78193-w