Abstract

A combination of multiple genetic and environmental factors appear to be required to trigger the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Early life environmental exposures have been reported to be risk factors for a variety of adult-onset diseases, so we used data from an online international ALS case–control questionnaire to estimate whether any of these could be risk factors for the clinical onset of ALS. Responses were obtained from 1,049 people aged 40 years or more, 568 with ALS and 481 controls. People with ALS were more likely to have been born and lived longer in a country area than in a city area, to have younger parents, and to have lower educational attainment and fewer years of education. No ALS-control differences were found in sibling numbers, birth order, adult height, birth weight, parent smoking, Cesarean delivery, or age of starting smoking. In conclusion, early life events and conditions may be part of a group of polyenvironmental risk factors that act together with polygenetic variants to trigger the onset of ALS. Reducing exposure to adverse environmental factors in early life could help to lower the risk of later developing ALS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The factors that trigger the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND), remain unclear1. Great strides have been made in finding genetic and epigenetic associations with ALS, particularly in the familial form of the disease (fALS)2. About half of the incidence of the sporadic form of the disease (sALS) is also considered to have some genetic or epigenetic components3. However, a single genetic or environmental factor is thought unlikely to explain what triggers the eventual adult onset of ALS. For example, a single factor cannot yet explain why in fALS a germline mutation, present at birth, only results in disease onset in later adult life, why fALS within individual families differs in disease penetrance and phenotype4, why it has been so difficult to find any environmental factors that can be confidently associated with ALS, and why there are global differences in ALS incidence5. It has therefore been proposed that ALS is a typical complex disease with multiple genetic/epigenetic and environmental steps, possibly a minimum of six, that eventually lead to a tipping point when the pathology becomes self-replicating, and the first disease symptoms appear6,7,8. This is likely to manifest as similar proportions of genetic/epigenetic variants and environmental exposures in sALS, and a large initial germline mutation followed by smaller somatic genetic and environmental steps in fALS (Fig. 1).

The multistep hypothesis for ALS. a In sporadic ALS, roughly the same proportions of genetic/epigenetic steps and environmental steps (of different exposure durations) eventually lead to a tipping point when ALS pathology becomes self-perpetuating. b In familial ALS, the largest step consists of a prenatal genetic mutation, with smaller genetic/epigenetic and environmental steps later triggering the clinical onset of ALS.

In contrast to the advances in understanding the genetic contributions to ALS, finding uncontested adverse environmental factors associated with the disease has been difficult. This lack of evidence has several potential causes: (1) The vast number of possible environmental risk factors (the exposome) for ALS, such as toxicants or infective agents, makes deciding which factors to pursue for investigation a major challenge9,10. (2) The probability that multiple environmental insults, all with small accumulative effect sizes, and that vary in composition among different people, are involved in ALS pathogenesis increases the complexity for detection. (3) The onset of clinical symptoms in people with ALS is usually in later adult life, but environmental exposures could have been years before, possibly in prenatal or early postnatal life, without traces of the agents persisting by the time ALS is diagnosed (a “hit-and-run” situation)11.

Numerous retrospective case–control studies have looked for possible environmental risk factors for ALS, but few have included the possibility that early life conditions could be ALS risk factors. Several adult-onset disorders, including ALS, have been linked to early life events such as birth or residence in country or city areas as well as parental age12,13, level of education14,15,16,17,18, sibling number and birth order13,19, adult height14,20,21 (adult height correlates with birth length22), birth weight23,24, parental smoking25,26,27, and Cesarean delivery28,29. A young age for starting smoking cigarettes is another potential early life risk factor for ALS30. We therefore used results from questions in an online international ALS risk factor questionnaire to see if any responses regarding early life events differed between people with ALS and controls.

Methods

Setting

This case–control study used data collected between January 2015 and May 2021 from an online questionnaire, ALS Quest, which was available in 36 languages31. Respondents for the questionnaire were formally recruited worldwide via national and state ALS Associations, national ALS registries, the Internet, and social media. When respondents were asked to choose from a list how they heard about the questionnaire, they nominated: ALS Association (ALS 52.5%, control 29.5%), Internet (ALS 15.8%, control 21.6%), Other (ALS 20.6%, control 18.3%), Person without ALS (ALS 1.1%, control 12.3%), Person with ALS (ALS 2.6%, control 10.6%), Community group (ALS 3.0%, control 3.3%), and Print and TV media (ALS 0.5%, control 0.0%).

No personally-identifying data were collected so respondents remained anonymous. Information on disease status was self-reported. Respondents for the study were limited to those aged 40 years or more at the time of completing the questionnaire to limit the number of controls who might later develop ALS.

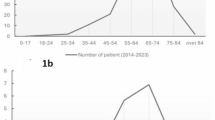

ALS cases were respondents who responded positively to the question “Do you have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease (ALS/MND) that has been diagnosed by a neurologist?”. Male ALS respondents had a mean age when completing the questionnaire of 61.9 y SD 8.9, and female ALS respondents a mean age of 61.5 y SD 9.4 y. They were not asked their age of disease onset. Median and interquartile ranges for ages (in both ALS and control groups) are shown in Fig. 2a. When presented with a drop-down list of the earliest symptom perceived by ALS respondents, replies were: Limb weakness (male 46.3% , female 45.9%), Difficulty swallowing (male 2.6%, female 2.3%), Slurred speech (male 14.7%, female 20.2%), Shortness of breath (male 0.6%, female 1.8%), Muscle twitches/fasciculations (male 10.9%, female 5.5%), Spasticity/increased muscle tone (male 1.8%, female 2.8%), Other (male 23.2%, female 26.1%). Slurred speech and difficulty swallowing, taken together as representative of bulbar weakness, was reported by 17.3% of males and 22.9% of females (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.1, X2 p = 0.125).

Controls were respondents who responded negatively to the question “Do you have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease (ALS/MND) that has been diagnosed by a neurologist?”. Male controls had a mean age when completing the questionnaire of 62.0 y SD 11.2 y, and female controls a mean age of 56.2 y SD 9.7 y. Controls had either a relative with ALS (39.9%), no specific connection with ALS (20.4%), a friend with ALS (9.8%), a spouse/partner with ALS (7.1%), or other connections with ALS (22.9%).

Other characteristics of ALS and control respondents are shown in Table 1.

Ethics

The project, “ALS-Quest: An online questionnaire for research into amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” (X14-357), was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Sydney Local Health District (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Zone). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Participants consented to submit their questionnaire responses by clicking an “I consent” button after acknowledging that they had read the preceding Information for Participants section of the questionnaire, and agreeing that they “Understand that I will not be asked for any personal information that could identify me, so the study is anonymous and strictly confidential” and that they “Freely choose to participate in the study and understand that I can withdraw my questionnaire answers at any time until I click the Submit button at the end of the questionnaire.”

Questions selected

Questions (in italics, followed by possible answers) were selected that reflected early-life conditions or events that had the potential to be ALS risk factors31. (1) Which of the following best describes the place you were born? Urban (population greater than 50,000)—Inner city; Urban (population greater than 50,000)—Suburb; Regional centre—population less than 50,000; Rural (non-farm); Rural (farm). (2) Please estimate the total number of years that you have lived in each the following types of environments. For people with ALS/MND, include only those places where you lived before you were diagnosed with ALS/MND. Urban (population greater than 50,000)—Inner city; Urban (population greater than 50,000)—Suburb; Regional centre—population less than 50,000; Rural (non-farm); Rural (farm). (3) Please enter your parents’ years of birth. Parent ages at offspring year of birth were calculated from (Offspring date of questionnaire consent-Offspring age)-Parent date of birth. (4) What is the highest level of education that you have completed? Primary (elementary) school; Secondary (high) school; Non-university diploma or certificate; University undergraduate degree (Bachelor); University postgraduate degree (Doctoral, Masters). (5) How many years of education have you had in total? If any of your education was part-time, please estimate the total in fulltime equivalent years. Number entered. (6) How many brothers and sisters (present and past) do you have? Please only include full siblings (that is, siblings with the same mother and father as yourself). Where do you come in the order of births of your brothers and/or sisters? Numbers entered. (7) What is your height? Number entered (in centimetres or feet and inches). (8) Do you have a written record of your birth weight that you can refer to? If Yes, What was your birth weight according to the written record? Number entered (in grams, kilograms, or pounds and ounces). (9) Did your mother and father ever smoke cigarettes? Yes/No. (10) Were you delivered by Cesarean section (c-section)? Yes/No. (11) Have you ever smoked cigarettes for at least once a week for six months or longer? Yes/No. What age did you start (smoking cigarettes)? Number entered.

Data analysis

GraphPad Prism 10 statistical software was used for: (1) 2 × 2 contingency testing with chi-square (X2) Fisher’s exact test for categorical data to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. (2) Assessing normality of continuous data with D’Agostino & Pearson tests. (3) Unpaired two-tailed t-tests for normal continuous data, with 95% confidence intervals of the mean. (4) Unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney U (MW) tests for non-normal continuous data, with effect size r (i.e., z/√N) when p ≤ 0.05 (z calculated on Planetcalc). Violin plots with medians and interquartile ranges were constructed to help interpretation of the Mann–Whitney analysed results32. (5) Chi-square tests for trend (X2Tr) for ordinal variables. (6) Normalisation of percentages (i.e., percentage of ALS cases/percentage of controls × 100) to compare trends between ALS cases and controls, either from categorical proportions, or from continuous partitions (from ALS-based terciles, quartiles, or quintiles)33. Significance was assessed at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

Results

Place of birth

The only individual birth site (out of rural farm, rural non-farm, regional, suburb, or inner city) with a significant odds ratio was suburb, with a decreased chance of ALS (OR 0.8, X2 p = 0.033) (Table 2). However, a trend was seen for ALS risk decreasing from higher risks in rural farm, rural non-farm, and regional sites through to lower risks in suburb and inner city sites (X2T p = 0.01) (Fig. 3a). The proportion of people with ALS born in a country area (a combination of rural farm, rural non-farm, and regional sites) was 45.7%, higher than that of those born in a city area (a combination of inner city and suburb sites) at 36.7% (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.9, X2 p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Country and city areas of living

People with ALS lived in a country area (rural farm, rural non-farm, and regional) for a longer time (median 15.0 y) than controls (median 6.0 y), MW p = 0.0004, r = 0.11 (with a difference in variances on F testing) (Fig. 2b). A comparison of age partitions showed an increased ALS risk in people who had lived ≥ 27 years in the country, and a decreased risk in people who had lived ≤ 2 years in the country (Table 2). A trend for increasing risk of ALS was seen with increasing numbers of years lived in a country area (X2Tr p = 0.004) (Fig. 3b).

Truncated violin plots showing distributions of continuous data. a Ages of respondents. b Years lived in country or city areas. c Proportion of life lived in country or city areas. d Ages of parents at time of respondent birth. e Years spent in education. f Adult body height. g Birth weight. h Age started smoking cigarettes. Dashed line: median, dotted lines: interquartile ranges.

Normalised data from questionnaire responses (ie, percentage of ALS respondents divided by percentage of control respondent × 100) to demonstrate risk trends for selected variables. Items above the dotted line at y = 100 indicate an increased proportion of people with ALS compared to controls, and below this line a decreased proportion of people with ALS compared to controls. a Place of birth. b Years spent in country areas. c Years spent in city areas. d Father age at respondent birth. e Mother age at respondent birth. f Highest level of education. g Years spent in education. h Age when started smoking cigarettes.

No significant differences between people with ALS and controls were seen in numbers of years spent living in a city area (suburb and inner city) (ALS median 43.0 y, control median 44.5 y) (Fig. 2b) or in age partitions for city living (Table 2), though there was tendency for people with ALS to have lived fewer (≤ 25) years in city areas (Fig. 3c).

People with ALS had spent a median of 26.1% of their lives in country areas compared to controls who spent a median of 10.4% of their lives in country areas (MW p = 0.0012, r = 0.10), with inverse results for city areas (Fig. 2c).

The proportions of people who had lived in both city and country areas were similar in both diagnostic groups (ALS 55.6%, controls 51.4%). Also similar were the proportions who had lived only in city areas (ALS 30.6%, controls 38.7%) or only in country areas (ALS 13.2%, controls 9.1%).

Parent ages at time of respondent birth

People with ALS had slightly younger fathers (median age 30 y) than controls (median age 32 y) MW p = 0.0073, r = 0.09 (Fig. 2d). Age partitions showed an increased ALS risk for people with young (≤ 25 y) fathers, and a decreased risk with older (≥ 37 y) fathers (Table 2). An age partition trend was seen for people with ALS to have younger fathers (X2T p = 0.017) (Fig. 3d).

People with ALS had slightly younger mothers (median age 28 y) than controls (median age 29 y) MW p = 0.0205, r = 0.08 (Fig. 2d). Age partitions showed an increased ALS risk for people with young (≤ 25 y) mothers, and particularly those aged ≤ 24 y (Table 2). An age partition trend was seen for people with ALS to have younger mothers (X2Tr p = 0.030) (Fig. 3e).

Education levels and years

A smaller proportion of people with ALS than controls had postgraduate degrees (ALS 18.5%, control 26.6%, X2 p = 0.002) (Table 2). A trend was seen for respondents with lower levels of education to have a greater likelihood of developing ALS: respondents who completed only secondary school were more likely to develop ALS, and those with postgraduate degrees were less likely to develop ALS (X2Tr p = 0.010) (Fig. 3f). Primary/elementary school values were not included in the trend analysis because of low response numbers.

Despite having the same median number of years of education in both groups (16.0 y), people with ALS spent overall fewer years in education than controls (MW p = 0.0008, r = 0.10), because they had a greater proportion of ALS respondents in the first tercile (≤ 14 y) and a smaller proportion in the third tercile (≥ 17 y) compared to controls32 (Table 2, Fig. 2e). A year partition trend was seen for people with ALS to have fewer years in education (X2Tr p = 0.014) (Fig. 3g).

Sibling number and birth order

Neither the median number of siblings (ALS 2.0 sibs; control 2.0 sibs), nor the trend in sibling numbers (none, 1, 2, 3, or ≥ 4), differed between people with ALS and controls (Table 2).

Birth order (1st, 2nd, or 3rd–11th) in respondents who had siblings did not differ between ALS respondents and controls (Table 2).

Height

Adult male height did not differ between ALS (median height 178 cm) and control (median height 178 cm) respondents, and no height partition trend was seen (Table 2, Fig. 2f). Similarly, adult female height did not differ between ALS (median height 163 cm) and control (median height 164 cm) respondents, with no height partition trend (Table 2, Fig. 2f).

Birth weight

Male mean birth weight did not differ between ALS (mean weight 3.6 kg SD 0.7) and control (mean weight 3.5 kg SD 0.7) respondents (Fig. 2g). Similarly, adult female mean birth weight did not differ between ALS (mean weight 3.3 kg SD 0.5) and control (mean weight 3.3 kg SD 0.7) respondents (Fig. 2g). No partition trend was seen in female birth weights (Table 2). Too few male birth weight responses were available to enable trend comparisons.

Parental smoking

The proportion of fathers of respondents who smoked cigarettes was similar in people with ALS (70.0%) and controls (69.1%), as was the proportion of mothers of respondents who smoked cigarettes (ALS 46.8%, controls 42.5%) (Table 2).

Cesarean delivery

The proportions of ALS respondents who reported being delivered by Cesarean section (3.7%) was similar to that of control respondents (4.5%) (Table 2).

Cigarette smoking

The age of starting smoking cigarettes was similar in ALS (median age 17.0 y) and control (median age 17.0 y) smokers (Fig. 2h), with no age partition trend for commencement of smoking in people with ALS (Table 2, Fig. 3h).

The proportion of ALS males who had ever smoked cigarettes (57.7%) was higher than that of control males (37.8%), X2 p = 0.0002. In females, the proportions who had ever smoked were similar between groups (ALS females 42.5%, control females 44.8%) (Table 2).

Discussion

Key findings of this study are that people with ALS are more likely to have been born in a country area than in a city area, to have lived longer in a country area, to have younger parents, to have lower educational attainment, and to have had fewer years in education. Effect sizes were small for these statistically-significant variables, consistent with the multistep hypothesis for ALS in which several factors, each with a modest adverse effect, accumulate until a disease-inducing tipping point is reached. This study found the same early-onset ALS risk factors detected in some previous studies12,13,14,15,16,17,18, and indicates what other early environmental risk factors could be explored in greater detail in future larger studies.

Being born or living in the country has been associated with various disorders34. Rural living could lead to exposure to farm-related herbicides and pesticides, a reported risk factor for ALS15,35,36,37. Exposure to rural bodies of water with harmful algal blooms that augment toxic mercury exposure could constitute a risk factor for ALS38,39,40,41. Rural place of birth and living could expose infants and young people more to the effects of seasonal changes such as increased humidity leading to infectious diseases that may be involved in ALS33,42. One small ALS case–control study did not detect differences between rural versus urban, or suburb versus urban, groups14. Similar proportions of people with ALS and controls had lived either in both city and country regions, or in only city or only country regions, so recruitment or selection bias based on city or country living would be unlikely.

A younger parental age has previously been suggested to be a risk factor for ALS12, and both low and high maternal ages have been reported to increase ALS risk13. Younger parents may be less wealthy than older ones43 and so provide a less well-resourced environment for their children, which could predispose to reduced survival44. It is difficult to ascertain whether an ALS risk due to younger parental age is due to the small differences in ages of the father, mother, or both, since younger people usually prefer partners of similar ages45.

Four other case–control studies have suggested people with ALS had lower educational attainment than controls, though participant numbers in some of these were modest14,15,16,17. A Mendelian randomisation study gave genetic support for a lower risk of ALS with higher educational attainment18. Education level and years spent in education are likely to affect choices of employment, with advanced levels of education leading to more white collar positions, and lower levels to more blue collar positions. People in occupations with a higher degree of manual skills appear more at risk of developing ALS, whereas occupations likely to be undertaken in an office environment seem to be protective46. This is possibly because the former types of occupations are more likely to have exposure to occupational toxins or high physical activity that could be risk factors for ALS36,47. There may be a link between ALS-associated lower educational levels and younger parent ages, since persisting lower socioeconomic circumstances that are related to younger parent ages43 could impede educational opportunities of the offspring. Lower educational levels could predispose some people to health risks such as smoking48, with some (but not all) studies suggesting that smoking is a risk factor for ALS30,49,50. Our male (but not female) ALS respondents were more likely to be smokers than controls, but the age of starting smoking did not differ between groups in our study, suggesting that the potential risk for ALS attributable to smoking arises from long-term smoking.

Previous studies of early life environmental risk factors for ALS include: (1) Season of birth, with births of ALS patients increasing between late summer and early winter in Australia, Sweden and Japan, with increased humidity in these seasons possibly leading to more infectious or allergic disorders33. (2) Increased prenatal exposure to testosterone, as shown by a lower index-to-ring finger ratio, has been postulated to be an ALS risk factor51, though this finding could not be replicated in a subsequent larger study52. (3) Early life exposure to toxic metals appears to be more likely in people with ALS, as judged by time series elemental analyses of teeth53. (4) Differences in innate personality types could play a part in early lifestyle choices, since people with ALS have higher rates of extraversion that could underlie increased smoking or exposure to trauma30,54,55.

This study has several limitations. (1) More male than female respondents were present in the ALS group, and more female than male respondents in the control group. However, ALS onset symptoms were similar between genders in the current study. The slightly increased proportion of bulbar symptoms in our female respondents is probably due to the increased age of ALS onset in females56, rather than to early environmental factors. Therefore, males and females were only analysed separately where gender differences are likely to be more marked, i.e., parental ages, smoking, height and birth weight. (2) Significance levels were not adjusted for multiple testing, since only biologically-relevant variables were tested, and we were looking for variables with even small effect sizes. (3) We had few respondents with only primary education levels, probably because the online nature of the questionnaire necessitated reasonably high level computer skills. (4) This was an international study, but not a truly global one, since few respondents were born in Africa, Asia, or South America. (5) Female controls were younger than female ALS respondents, but this is unlikely to have affected the results of this study with its focus on early life events, and the minimum age for inclusion in the study was 40 years. (6) More ALS cases came from North America and more controls from Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), but these countries have populations of similar mixed heritages, cultures, and life styles, so this is unlikely to have had a major impact on early life events. (7) The diagnosis of ALS was self-reported for the questionnaire, but self-reporting of an ALS diagnosis has been shown to be highly reliable57. (8) In the large-sample Mann–Whitney test, small differences between population variances (present for example in years spent in country living) increase the Type I error rate.

Future studies of early environmental risk factors for ALS face considerable challenges, given the vast number of potential “exposome” factors and the difficulty of finding large numbers of people with ALS who have records of early events and conditions. Prospective studies of early life events in countries that have comprehensive population registries containing both genetic and life-long environmental data could give useful information, using standard neurological diagnostic criteria for ALS. However, these data take many years to collect for a late-onset and relatively uncommon disorder such as ALS. Comparisons of large ALS and well-matched controls groups from the same country would overcome many of the limitations of the present self-completed online study. Such studies would allow more detailed statistical analyses of the data, for example: stratifying the analyses by gender, age and site of disease onset; estimating potential interactions between observed factors; calculating the number of steps for significant exposures7,8; looking for covariates of interest for factors that could account for recruitment or selection bias, such as years lived in the country or educational level; and undertaking sensitivity analyses of outcomes related to different well-defined control types.

Despite the challenges to identify the multiple steps leading to ALS, including potentially early life events, prospects that should encourage further research into this topic are: (1) Finding even one of the steps and being able to prevent it or reverse it, could disrupt the multistep chain and prevent the onset of ALS onset or slow disease progression. (2) If the majority of the six factors are genetic or epigenetic in origin, whole genome approaches may identify them. (3) Studies looking for large numbers of ALS environmental risk factors simultaneously could be of value. This approach is now taken by genetic researchers, with searches for single gene variants largely replaced by whole exome or genome analyses. One method would be to look for evidence of previous exposures to multiple toxic environmental agents using nails, teeth, or striated muscle41,53,58. Regions of the brain that store toxic metals long-term, such as the locus ceruleus in the brain stem59, could be examined for circulating toxic elements that have entered the nervous system through the blood–brain barrier. A similar multiple environmental factor detection approach has been used to look for steps involving toxic metals in cancers60, and the causes of cancer progression have been compared to the steps leading to ALS7. The increasing incidence of ALS61 could be due to increasing toxic metal and chemical environmental pollution62, making the search for such toxicants in ALS an urgent task.

In conclusion, this study indicates that a range of early life events and conditions could represent initial steps in the multistep path to ALS. Despite the challenges to finding all the genetic/epigenetic and environmental factors that underlie ALS, further research into this area of research is to be encouraged in an attempt to disrupt the chain of these events before they have a chance to trigger the disease.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Feldman, E. L. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 400, 1363–1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01272-7 (2022).

Al-Chalabi, A., van den Berg, L. H. & Veldink, J. Gene discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Implications for clinical management. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.182 (2017).

Shatunov, A. & Al-Chalabi, A. The genetic architecture of ALS. Neurobiol. Dis. 147, 105156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105156 (2021).

Van Daele, S. H. et al. Genetic variability in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 146, 3760–3769. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad120 (2023).

Logroscino, G. & Piccininni, M. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis descriptive epidemiology: The origin of geographic difference. Neuroepidemiology 52, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1159/000493386 (2019).

Al-Chalabi, A. & Hardiman, O. The epidemiology of ALS: A conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 617–628. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203 (2013).

Al-Chalabi, A. et al. Analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as a multistep process: A population-based modelling study. Lancet. Neurol. 13, 1108–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(14)70219-4 (2014).

Chio, A. et al. The multistep hypothesis of ALS revisited: The role of genetic mutations. Neurology 91, e635–e642. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005996 (2018).

Al-Chalabi, A. & Pearce, N. Commentary: Mapping the human exposome: Without it, how can we find environmental risk factors for ALS?. Epidemiology 26, 821–823. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000381 (2015).

Wolfson, C., Gauvin, D. E., Ishola, F. & Oskoui, M. Global prevalence and incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review. Neurology 101, e613–e623. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000207474 (2023).

Pamphlett, R. The “somatic-spread” hypothesis for sporadic neurodegenerative diseases. Med. Hypotheses. 77, 544–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.06.027 (2011).

Hawkes, C. H., Goldblatt, P. O., Shewry, M. & Fox, A. J. Parental age and motor neuron disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 52, 618–621. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.52.5.618 (1989).

Fang, F., Kamel, F., Sandler, D. P., Sparen, P. & Ye, W. Maternal age, exposure to siblings, and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 1281–1286. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn056 (2008).

Qureshi, M. M. et al. Analysis of factors that modify susceptibility and rate of progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. 7, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820600640596 (2006).

Malek, A. M. et al. Environmental and occupational risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case-control study. Neurodegener. Dis. 14, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355344 (2014).

Yu, Y. et al. Environmental risk factors and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A case-control study of ALS in Michigan. PLoS One 9, e101186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101186 (2014).

Sutedja, N. A. et al. Lifetime occupation, education, smoking, and risk of ALS. Neurology 69, 1508–1514. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000277463.87361.8c (2007).

Zhang, L., Tang, L., Xia, K., Huang, T. & Fan, D. Education, intelligence, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A Mendelian randomization study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 7, 1642–1647. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51156 (2020).

Vivekananda, U. et al. Birth order and the genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. 255, 99–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-007-0709-2 (2008).

Nunney, L. Size matters: Height, cell number and a person’s risk of cancer. Proc. Biol. Sci. 285, 1743. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1743 (2018).

Krieg, S. et al. The association between body height and cancer: a retrospective analysis of 784,192 outpatients in Germany. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 4275–4282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04335-0 (2023).

Eide, M. G. et al. Size at birth and gestational age as predictors of adult height and weight. Epidemiology 16, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000152524.89074.bf (2005).

Wilcox, A. J. On the importance–and the unimportance–of birthweight. Int. J. Epidemiol. 30, 1233–1241. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.6.1233 (2001).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association of birth and childhood weight with risk of chronic diseases and multimorbidity in adulthood. Commun. Med. (Lond.) 3, 105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-023-00335-4 (2023).

de la Chica, R. A., Ribas, I., Giraldo, J., Egozcue, J. & Fuster, C. Chromosomal instability in amniocytes from fetuses of mothers who smoke. JAMA 293, 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.10.1212 (2005).

Liu, Y. et al. Effects of paternal exposure to cigarette smoke on sperm DNA methylation and long-term metabolic syndrome in offspring. Epigenetics Chromatin. 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13072-022-00437-8 (2022).

Parmar, P. et al. Association of maternal prenatal smoking GFI1-locus and cardio-metabolic phenotypes in 18,212 adults. EBioMedicine 38, 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.066 (2018).

Kristensen, K. & Henriksen, L. Cesarean section and disease associated with immune function. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 587–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.040 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1910236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10236 (2019).

Kim, K. et al. Association of smoking with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and dose-response analysis. Tob Induc Dis 22, 175731. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/175731 (2024).

Parkin Kullmann, J. A., Hayes, S., Wang, M. X. & Pamphlett, R. Designing an internationally accessible web-based questionnaire to discover risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case-control study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 4, e96. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.4840 (2015).

Hart, A. Mann-Whitney test is not just a test of medians: Differences in spread can be important. BMJ 323, 391–393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7309.391 (2001).

Pamphlett, R. & Fang, F. Season and weather patterns at time of birth in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. 13, 459–464. https://doi.org/10.3109/17482968.2012.700938 (2012).

Monette, M. Rural life hardly healthier. CMAJ. 184, E889-890. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4289 (2012).

Malek, A. M., Barchowsky, A., Bowser, R., Youk, A. & Talbott, E. O. Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies: Pesticide exposure as a risk factor for ALS. Environ. Res. 117, 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2012.06.007 (2012).

Pamphlett, R. Exposure to environmental toxins and the risk of sporadic motor neuron disease: an expanded Australian case-control study. Eur. J. Neurol. 19, 1343–1348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03769.x (2012).

Longinetti, E. et al. Geographical clusters of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the Bradford Hill criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. Frontotemporal. Degener. 23, 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2021.1980891 (2022).

Lei, P. et al. Algal organic matter drives methanogen-mediated methylmercury production in water from eutrophic shallow lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 10811–10820. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c08395 (2021).

Torbick, N. et al. Assessing cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms as risk factors for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotox. Res. 33, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-017-9740-y (2018).

Main, B. J. et al. Detection of the suspected neurotoxin beta-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in cyanobacterial blooms from multiple water bodies in Eastern Australia. Harmful Algae 74, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2018.03.004 (2018).

Pamphlett, R. & Bishop, D. P. The toxic metal hypothesis for neurological disorders. Front. Neurol. 14, 1173779. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1173779 (2023).

Castanedo-Vazquez, D., Bosque-Varela, P., Sainz-Pelayo, A. & Riancho, J. Infectious agents and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Another piece of the puzzle of motor neuron degeneration. J. Neurol. 266, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8919-3 (2019).

van Roode, T., Sharples, K., Dickson, N. & Paul, C. Life-course relationship between socioeconomic circumstances and timing of first birth in a birth cohort. PLoS One 12, e0170170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170170 (2017).

Carslake, D., Tynelius, P., van den Berg, G. J. & Davey Smith, G. Associations of parental age with offspring all-cause and cause-specific adult mortality. Sci. Rep. 9, 17097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52853-8 (2019).

Botzet, L. J. et al. The link between age and partner preferences in a large, international sample of single women. Hum. Nat. 34, 539–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-023-09460-4 (2023).

Pamphlett, R. & Rikard-Bell, A. Different occupations associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Is diesel exhaust the link?. PLoS One 8, e80993. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080993 (2013).

Chapman, L., Cooper-Knock, J. & Shaw, P. J. Physical activity as an exogenous risk factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review of the evidence. Brain 146, 1745–1757. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac470 (2023).

Silventoinen, K. et al. Smoking remains associated with education after controlling for social background and genetic factors in a study of 18 twin cohorts. Sci. Rep. 12, 13148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17536-x (2022).

Opie-Martin, S. et al. UK case control study of smoking and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. Frontotemporal. Degener. 21, 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2019.1706580 (2020).

Pamphlett, R. & Ward, E. C. Smoking is not a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in an Australian population. Neuroepidemiology 38, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1159/000336013 (2012).

Vivekananda, U. et al. Low index-to-ring finger length ratio in sporadic ALS supports prenatally defined motor neuronal vulnerability. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 635–637. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2010.237412 (2011).

Parkin Kullmann, J. A. & Pamphlett, R. Does the index-to-ring finger length ratio (2D:4D) differ in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? Results from an international online case-control study. BMJ Open. 7, e016924. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016924 (2017).

Figueroa-Romero, C. et al. Early life metal dysregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51006 (2020).

Parkin Kullmann, J. A., Hayes, S. & Pamphlett, R. Are people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) particularly nice? An international online case-control study of the big five personality factors. Brain Behav. 8, e01119. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1119 (2018).

Gu, D. et al. Trauma and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Amyotroph. Lateral. Scler. Frontotemporal. Degener. 22, 170–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2020.1861024 (2021).

Grassano, M. et al. Sex differences in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis survival and progression: A multidimensional analysis. Ann. Neurol. 96, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26933 (2024).

Malek, A. M., Stickler, D. E., Antao, V. C. & Horton, D. K. The national ALS registry: A recruitment tool for research. Muscle Nerve 50, 830–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24421 (2014).

Andrew, A. S. et al. Toenail mercury levels are associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis risk. Muscle Nerve. Epub. date 10, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26055 (2018).

Pamphlett, R. et al. Concentrations of toxic metals and essential trace elements vary among individual neurons in the human locus ceruleus. PLoS One 15, e0233300. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233300 (2020).

Pamphlett, R. & Bishop, D. P. Elemental biomapping of human tissues suggests toxic metals such as mercury play a role in the pathogenesis of cancer. Front. Oncol. 14, 1420451. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1420451 (2024).

Imrell, S., Fang, F., Ingre, C. & Sennfalt, S. Increased incidence of motor neuron disease in Sweden: A population-based study during 2002–2021. J. Neurol. 271, 2730–2735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-024-12219-1 (2024).

Streets, D. G. et al. All-time releases of mercury to the atmosphere from human activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 10485–10491. https://doi.org/10.1021/es202765m (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank ALS and control participants who completed the extensive ALS Quest questionnaire. World-wide national and state-based ALS Associations, the International Alliance of ALS/MND Associations, the USA CDC National ALS Registry, and the Canadian Neuromuscular Disease Registry assisted in recruiting respondents for the questionnaire. Volunteers translated the English-language questionnaire into different languages. R. P. is supported by the Aimee Stacey Memorial and Ignacy Burnett Bequests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. P. and J. A. P. K. conceived the study, designed and implemented the questionnaire, undertook the investigation, analysed the results, and reviewed, edited, and approved the submitted article. R. P. administered the project, supplied financing, and wrote the original draft.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pamphlett, R., Parkin Kullmann, J. Early life events may be the first steps on the multistep path to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep 14, 28497 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78240-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78240-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

ALS: a field in motion

Scientific Reports (2025)