Abstract

Studies on the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are limited. We aimed to examine the association between DII and CKD among U.S. adults with particular attention paid to sex differences. A total of 19317participants were included in this study. The exposure variable was DII, which was calculated based on overall inflammatory effect scores. The outcome was CKD, defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or urinary albumin/creatinine (uACR) ≥ 30 mg/g. The mean (SD) of age our study participants was 47.84 (18.35); and the mean (SD) of DII was 1.50 (1.91) (median 1.74). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, we observed that the OR value (95%CI) of CKD is 1.19 (1.14, 1.23), 1.12 (1.06, 1.19), and 1.16 (1.06, 1.27) in models 1, 2 and 3 for Per SD increment of DII. Compared with Participants with Q1(DII < 0.15), the adjusted ORs for participants in Q2 (0.15 ≤ DII < 1.74), Q3 (1.74 ≤ DII < 3.02) and Q4 (≥ 3.02)were 1.46 (95% CI 1.14–1.88), 1.55 (95% CI 1.20–1.99) and 1.52 (95% CI 1.17, 1.98) ( p for trend < 0.05), respectively. However, this study observed that the independent positive correlation between DII and CKD appeared in women rather than men. Higher DII levels were significantly and linearly associated with an increased prevalence of chronic kidney disease, and sex modified the association. This suggests that gender-specific dietary interventions can be developed to reduce the risk of CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a global public health problem, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is related to serious morbidity, mortality and high utilization rate of medical resources1. According to the analysis of global disease burden research in 2017, there are 697.5 million CKD patients worldwide, with an estimated prevalence rate of 9.1%; And 1.2 million patients died of CKD2. Traditional risk factors of CKD are hypertension, diabetes, obesity and proteinuria3,4. Accordingly, besides controlling the above risk factors, new and effective strategies are needed to prevent the occurrence and development of CKD and related complications.

There is a close relationship between the pathological process of chronic kidney disease and chronic inflammation5. Previous epidemiological studies have shown that the increase of inflammatory indicators will significantly increase the risk of CKD and related cardiovascular events (CVD)6,7,8. As a matter of fact, previous studies have consistently proved that dietary factors can affect chronic inflammation9,10. So, shivappa et al. quantified the dietary components of different diets and developed a tool to determine the potential inflammation of individual diet11, which was verified by inflammatory biomarkers in different populations12,13,14. Previous studies have shown that the DII is associated with the prevalence of CKD in the adult population in the United States. An inflammatory diet has been found to be associated with a higher prevalence of CKD, but it is not clear whether there are differences between different subgroups15. In CKD patients, a higher DII is associated with an increased risk of advanced CKD, but the statistical analysis did not include the confounding variable of gender16. The aim of this study was to assess whether gender modulates the association between the DII and CKD, which fills the gaps in the above-mentioned studies.

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was performed using aggregated data from 8 years (2011–2018) of NHANES, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The project adopted a stratified multistage sampling method and was an ongoing repeated cross-sectional study to assess the health and nutrition status of adults and children in the United States17. The NHANES survey began in 1960s, mainly including interviews and physical examinations.The study has been conducted every two years since 1999; About 5,000 participants are selected for data collection every year18. Before the investigation, all participants provided written informed consent. And this survey was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics. More detailed information can be obtained from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

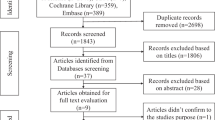

Participants from the general population who took part in NHANES from 2011 to 2018 were included, with the following exclusion criteria: (1) Age under 18; (2) Failure to complete the dietary questionnaire and provide blood samples; (3) Missing data for DII, uACR, and eGFR. Ultimately, a total of 19,317 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Trainers collect socio-demographic and lifestyle information, including age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, smoking, alcohol consumption, disease history and medication history, through standardized family interview questionnaires. Anthropometric indicators include height, weight and blood pressure (BP). Body height and weight were collected without shoes and thick clothes, and measured with a medical scale. Body mass index (BMI), in kg/m2, was calculated as the weight divided by the height squared. According to the standard blood pressure measurement protocol recommended by American Heart Association at that time, mercury sphygmomanometer was used to measure blood pressure. Three blood pressure readings were obtained continuously from the same arm. This study defined systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) as the average of three blood pressure measurements.

Every subject was asked to do an overnight rapid venous blood sample from all study participants. The DcX800 method is used to measure the albumin concentration as a bichromatic digital endpoint method. Using Roche Hitachi 717 and 912 analyzers (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG) and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) cholesterol were measured by enzymatic method. Creatine were assessed using automated biochemical profiling (Beckman Synchron LX20; Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, California, United States). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is calculated from measured values of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-cholesterol. Urine albumin was measured using solid-phase fluorescent immunoassay, and urine creatinine was measured using the Roche/Hitachi Modular P Chemistry Analyzer in 2011 and Roche/Hitachi Cobas 6000 chemistry analyzer in 2013; urine albumin and creatinine levels were standardized and calibrated with the gold standard method according to the recommendations of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Urine albuminto-creatinine ratio (uACR) = urine albumin/urine creatinine. According to Roche Hitachi 911 analyzer, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was measured by hexokinase method. The formula used for the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation[20]. Diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes or FPG concentration ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or use of glucose-lowering drugs. Cardiovascular disease and stroke are derived from the following questionnaire data: presence or absence of coronary heart disease/presence or absence of angina pectoris/presence or absence of myocardial infarction/presence or absence of stroke/presence or absence of congestive heart failure. Diagnosis of hypertension is determined based on the answers to the questionnaire about the presence or absence of hypertension. Further details of data collection can be found in https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx.

Defnition of the DII and CKD

The exposure variable in this study is the dietary inflammation index. DII score is based on the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties of 45 different food ingredients to assess the impact of diet on inflammation. This index was developed through a systematic review of 2,000 published research articles11. DII scores contain positive and negative values, positive values represent pro-inflammatory diets, while negative values correspond to more anti-inflammatory diets11. For this analysis, we calculated the DII value by the average nutritional intake on the first day of 24-hour meal recall. Such food components include energy, carbohydrate; protein; total fat; dietary fiber; cholesterol; saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids; ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids; vitamins A, B1, B2, B3(niacin), B6, B12, C, D, and E; folic acid; alcohol; beta-carotene; caffeine; iron; magnesium; zinc; and selenium19,20. Based on the above food ingredients, we calculate the DII score. DII calculation formula: Zscore = [(average daily intake − global average daily intake)/standard deviation]; Zscore1 = Zscore → (converted to percentile)× 2 − 1; the DII is obtained by multiplying Zscore1 with the inflammation effect score of each food ingredient and then summing the results. The global intake standard values, standard deviations and inflammation effect scores are provided in the study by Shivappa N et al. i.e21. The diagnostic criteria for chronic kidney disease (CKD) are based on international guidelines: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or proteinuria of at least 30 mg/g22.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. The statistical packages R (http://www.r-project.org) and Empower (R) (http://www.empowerstats.com) were used to perform all statistical analyses.

Baseline characteristics are presented as means ± SDs for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables according to DII quartiles. ANOVA or Chi-squared tests were used to compare the significant differences in population characteristics. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the association between DII and the prevalence of CKD among all participant, males and females. Covariates were included as potential confounders in the final multivariate logistic regression models if they changed the estimates of DII for CKD by more than 10%23or were known as traditional risk factors for CKD. We built sequential regression models as follows: Model 1 was a crude model. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake. Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs. We used a generalized additive model and a fitted smoothing curve (penalized spline method) to assess the dose-response association between DII and the prevalence of CKD. In addition, subgroup analyses were conducted to further verify the gender difference in the prevalence of DII and CKD and to assess whether differences also existed in other subgroup variables, including: age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65, years), BMI (< 25 vs. ≥ 25, kg/m2), Gender (Male vs. Female), race (non-hispanic white vs. non-hispanic black vs. mexican american vs. other hispanic vs. other races), current smoking (never vs. former vs. now), alcohol intake (< 3 vs. ≥ 3, drinks per day), and diabetes mellitus (no vs. yes). Potential interactions were examined by including the interaction terms into the logistic regression models.

Results

Study participants and baseline characteristics

As described in Fig. 1 19317 participants from 4 NHANES cycles were included in the final study. Of the 19,371 participants, 9413 (48.73%) were males, 3100 (16.22%) were diabetes, and 3332 (17.25%) was CKD. The mean (SD) of age was 47.84 (18.35); the mean eGFR (SD) was 95.9 (24.4); the mean uACR (SD) was 45.1 (341.2); and the mean (SD) of DII was 1.50 (1.91) (median 1.74). Baseline characteristics of study participants according to the quartiles of DII are showed in Table 1. Participants with Q4(≥ 3.02) of DII were more likely to be females, to be non-hispanic white, to be current smokers, to have higher educational levels, to have higher values in BMI, and SBP, to have higher rate diabetes mellitus, to have higher rate of cardiovascular disease, to have higher rate stroke; to have higher rate hypertension; to have higher rate the usage of antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs and glucose-lowering drugs; and to have lower values in DBP, poverty income ratio, TC, HDL-C, albumin, and eGFR than those of the other three groups. At the same time, we observed the no differences between DII quartiles in age, alcohol intake, FPG, TG, LDL-C, and uACR (all P > 0.05).

Associations between DII and CKD

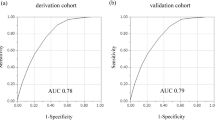

The relationship between DII and CKD are shown in Table 2. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, we observed that the OR value (95%CI) of CKD is 1.19 (1.14, 1.23), 1.12 (1.06, 1.19), and 1.16 (1.06, 1.27) in models 1, 2 and 3 for Per SD increment of DII. For sensitivity analysis, we changed DII from continuous variable to classified variable. Compared with Participants with Q1(DII < 0.15), the adjusted ORs for participants in Q2 (0.15 ≤ DII < 1.74), Q3 (1.74 ≤ DII < 3.02) and Q4 (≥ 3.02)were 1.46 (95% CI 1.14–1.88), 1.55 (95% CI 1.20–1.99) and 1.52 (95% CI 1.17, 1.98) ( p for trend < 0.05), respectively after adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs. The smoothing curve showed that a positive association existed between DII and the prevalence of CKD in US adults (Fig. 2). However, this study observed that the independent positive correlation between DII and CKD appeared in women rather than men.(Table 2; Fig. 3).

Association between DII and the prevalence of CKD. A linear association between DII and the prevalence of CKD was found (P < 0.05). The solid line and dashed line represent the estimated values and their corresponding 95% confidence interval. Adjustment factors included age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs.

Association between DII and the prevalence of CKD by sex. A linear association between DII and the prevalence of CKD by sex was found (P < 0.05). The solid line and dashed line represent the estimated values in male and female, respectively. The adjustment factors included age, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs.

Subgroup analyses

A stratified analysis was evaluated the relationship between DII (continuous variable) and the prevalence CKD in various subgroups (Fig. 4). The effect of DII on CKD showed no significant difference in the following subgroups: age (< 65 vs. ≥65, years), BMI (< 25 vs. ≥25, kg/m2), race (non-hispanic white vs. non-hispanic black vs. mexican american vs. other hispanic vs. other races), current smoking (never vs. former vs. now), alcohol intake (< 3 vs. ≥3, drinks per day), and diabetes mellitus (no vs. yes) in both groups (all P for interactions > 0.05) after adjustment for age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs except for the stratifying variable (Fig. 4). In the gender subgroup, after adjusting for the above variables, the effect of DII on CKD was significantly different, which was more pronounced in women, and P for interactions = 0.042.

Stratified analyses by potential modifiers of the association between DII and the prevalence of CKD. Each subgroup analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, poverty income ratio, BMI, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, TG, TC, HDL, LDL, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs, glucose-lowering drugs except for the stratifying variable.

Discussion

A cross-sectional study involving 19,317 participants was conducted in this study. The results show that the positive correlation between DII and CKD is independent of the following covariates such as age, gender, race, poverty-income ratio, body mass index, SBP, DBP, current smoking, alcohol intake, FPG, albumin, triglyceride, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, diabetes, antihypertensive drugs, lipoprotein-lowering drugs and hypoglycemic drugs. There is a linear positive correlation between DII and CKD in women, not men.

Previous studies related to DII and CKD are limited, with only two studies. Rouhani and his colleagues15 evaluated the association between DII and renal function indicators and the progression of kidney disease in 221 patients with CKD; This study shows that DII has nothing to do with renal function indexes (blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (Cr) as well as eGFR) in the fully adjusted model; however, higher DII scores are significantly related to the increased risk of CKD progression (OR: 2.12 ; 95% CI 1.05, 4.26). The large cross-sectional study conducted by Mazidi et al.16 included 21,649 participants. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between DII and renal function and CKD prevalence among American adults. The main conclusions are as follows: the increase of DII level is positively correlated with the increase of urinary albumin, uric acid, creatinine and the decrease of eGFR, and the prevalence of CKD in the highest DII quartile was 29% higher than that in the lowest DII quartile. Pro-inflammatory diet is related to decreased renal function and high prevalence of CKD.

We found that our results are consistent with the above studies. However, this study found the gender difference between DII and CKD for the first time. In our study, we found that the positive correlation between DII and CKD prevalence only appeared in women, not men. As shown in Table 2, in the fully adjusted model, the prevalence of CKD increased by 25% for every standard deviation of DII level of female participants. When DII was transformed into a categorical variable, the participants in the lowest group Q1 (DII < 0.63) served as the reference group, and the participants in the highest group Q4 (DII ≥ 3.27) increased the risk of CKD by 73% (P for trend < 0.05). Among men, DII has no relationship with CKD, whether it is a continuous variable or a categorical variable.

For the time being, the underlying pathological process between DII and CKD is not clear, so here’s a guess. Pathological and physiological process of CKD is based on low-grade chronic inflammation24. Inflammation, coagulation dysfunction and neutrophil-endothelial cell interaction are considered to play a role in the occurrence of kidney damage, which may lead to chronic kidney damage25. It may be that diet plays an important role in regulating chronic inflammation26and kidney health. The design of DII is used to evaluate different anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory dietary components and quantify dietary inflammation. Therefore, with the increase of DII, the risk of CKD prevalence rate is significantly increased. Our study indicates that the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII) is more strongly associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in women, which can be explained from three perspectives: First, women are more sensitive to inflammatory factors. A large prospective cohort study involving 6,814 U.S. communities found that the levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in American women were significantly higher than those in men, suggesting a greater propensity for chronic inflammation27. Second, women’s dietary habits differ from those of men; they may be more inclined to consume foods rich in antioxidants, which could enhance the impact of DII on women. Lastly, women may face higher levels of psychological stress and a greater risk of depression, factors that can lead to unhealthy eating habits and further increase the risk of developing CKD. Among men, our study is the first to find that there is no independent positive correlation between DII and CKD. The reason for this phenomenon is that, on the one hand, differences in baseline characteristics between men and women may lead to different effects of dietary inflammatory index on kidney health. For example, men may differ from women in certain metabolic or lifestyle factors (such as exercise levels, smoking, drinking, etc.), and these factors may have a more significant impact on kidney health when DII is high. The downward trend of DII in men may be due to these differences, which mitigate the negative impact of high DII on CKD. On the other hand, men may develop some kind of adaptive mechanism or protective response under conditions of high DII, thereby reducing the impact of dietary inflammatory response on CKD. This adaptive response may reduce the burden on the kidneys when the DII exceeds a certain threshold.

There are some limitations to our study. First, this is a cross-sectional study and no causal relationship between DII and CKD can be established. Second, although adjustments were made for a sufficient number of variables, there may be unmeasured confounding factors. For example, structural or functional kidney abnormalities and some environmental or occupational exposures. In addition, the study was conducted only in individuals from the US population, and further studies in larger populations are necessary to confirm whether the results are applicable to other populations. Finally, the study only assessed information from a single 24-hour dietary recall in the included population and did not dynamically track subsequent dietary conditions. Therefore, the prognostic implications of dynamic fluctuations in the DII index remain to be studied.

Conclusions

In summary, the DII-measured pro-inflammatory dietary pattern affects the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in US adults, with higher levels of DII being significantly and linearly associated with the prevalence of CKD, and with sex differences, observed only in women but not in men. The findings of this study will highlight the importance of personalised dietary management in CKD prevention, which will provide further evidence to support the role of diet in chronic disease prevention and offer practical avenues for clinical and public health applications to improve kidney health and overall health.

Practical application

Our study quantifies dietary inflammation using the DII and examines its association with CKD. Additionally, significant gender disparities are identified, providing valuable insights for tailoring dietary interventions in male and female patients at risk of CKD.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Kao, H. Y. et al. Associations between sex and risk factors for Predicting chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031219 (2022).

Global and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 395:709–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. (2020).

Muntner, P. et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in adults with CKD: results from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 55, 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.014 (2010).

El Minshawy, O., Ghabrah, T. & El Bassuoni, E. Diabetic nephropathy as a cause of end-stage renal disease in Tabuk area, Saudi Arabia: a four-year study. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 25, 1105–1109. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.139967 (2014).

Miyamoto, T., Carrero, J. J. & Stenvinkel, P. Inflammation as a risk factor and target for therapy in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 20, 662–668. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834ad504 (2011).

Kadatane, S. P., Satariano, M., Massey, M., Mongan, K. & Raina, R. The Role of Inflammation in CKD. Cells. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12121581 (2023).

Jaiswal, S. & Libby, P. Clonal haematopoiesis: connecting ageing and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-019-0247-5 (2020).

Liberale, L. et al. Inflammation, Aging, and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 79, 837–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.017 (2022).

Barbaresko, J., Koch, M., Schulze, M. B. & Nöthlings, U. Dietary pattern analysis and biomarkers of low-grade inflammation: a systematic literature review. Nutr. Rev. 71, 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/nure.12035 (2013).

Shivappa, N. Diet and chronic diseases: is there a mediating effect of inflammation. Nutrients. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071639 (2019).

Shivappa, N., Steck, S. E., Hurley, T. G., Hussey, J. R. & Hébert, J. R. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public. Health Nutr. 17, 1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013002115 (2014).

Kotemori, A. et al. Validating the dietary inflammatory index using inflammatory biomarkers in a Japanese population: a cross-sectional study of the JPHC-FFQ validation study. Nutrition. 69, 110569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2019.110569 (2020).

Tabung, F. K. et al. Development and validation of an empirical Dietary Inflammatory Index. J. Nutr. 146, 1560–1570. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.115.228718 (2016).

Wirth, M. D. et al. Construct validation of the Dietary Inflammatory Index among African americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 21, 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0775-1 (2017).

Rouhani, M. H. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and its association with renal function and progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 29, 237–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.09.001 (2019).

Mazidi, M., Shivappa, N., Wirth, M. D., Hebert, J. R. & Kengne, A. P. Greater Dietary Inflammatory Index score is associated with higher likelihood of chronic kidney disease. Br J Nutr. 120, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114518001071 (2018).

Curtin, L. R. et al. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample Design, 1999–2006. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–39 (2012).

Johnson, C. L., Dohrmann, S. M., Burt, V. L. & Mohadjer, L. K. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011–2014. Vital Health Stat. 2, 1–33 (2014).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Li, A., Chen, Y., Schuller, A. A., van der Sluis, L. & Tjakkes, G. E. Dietary inflammatory potential is associated with poor periodontal health: a population-based study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 48, 907–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13472 (2021).

Shivappa, N. et al. A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal variation of blood cholesterol study (SEASONS). Public. Health Nutr. 17, 1825–1833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013002565 (2014).

Shivappa, N., Steck, S. E., Hurley, T. G., Hussey, J. R. & Hébert, J. R. Designing and developing a literature derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 17, 1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013002115 (2014).

KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 100, S1-S276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.021 (2021).

Greenland, S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am. J. Public. Health. 79, 340–349. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.79.3.340 (1989).

Leung, K. C., Tonelli, M. & James, M. T. Chronic kidney disease following acute kidney injury-risk and outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 9, 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2012.280 (2013).

Giugliano, D., Ceriello, A. & Esposito, K. The effects of diet on inflammation: emphasis on the metabolic syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.052 (2006).

Lakoski, S. G. et al. Gender and C-reactive protein: data from the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Am. Heart J. 152, 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.015 (2006).

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to all of the NHANES participants who freely gave their time to make this and other studies possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XX and HH participated in literature search, study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. HH and JY conceived of the study, and participated in its coordination, data collection and analysis. MXL participated in study design and provided the critical revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants provided written informed consent. And this survey was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, H., Xiao, X., Yang, J. et al. Sex differences in the association of dietary inflammatory index with chronic kidney disease in US adults. Sci Rep 14, 30235 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78307-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78307-4