Abstract

Rodent migraine models have been developed to study the underlying molecular mechanisms of migraine, but these need further development and validation to stay relevant. The glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) mouse model with tactile hypersensitivity as the primary readout, has been highly used to understand the pathophysiology of migraine. Nevertheless, this readout has questionable translatability to the experience of spontaneous pain and additional readouts are needed to improve this model. We explored the applicability of several spontaneous behaviours and burrowing activity as additional markers to detect effects of repeated GTN injections in mice. We used the Laboratory Animal Behaviour Observation Registration and Analysis System (LABORAS) test system to understand the potential effect of GTN on locomotion and other behavioral parameters in two different experiments. Burrowing was used to investigate the potential effect on GTN on a voluntary innate behavior of mice. We found no clear effect of GTN on either locomotion or burrowing in these experiments. With our experimental design, there was no significant difference between GTN and vehicle and neither locomotion nor burrowing activity will readily supplement the von Frey test. The search for additional none-evoked markers of pain in rodent migraine models will continue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

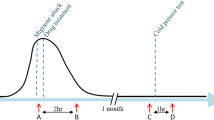

Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women1. It is characterized by pulsating, moderate to severe headache with aggravation of pain during physical activity, photo- and/or phonophobia, nausea and vomiting2. Despite decades of research into the pathophysiology of migraine, the exact mechanisms are still not fully elucidated. Human migraine provocation models have enabled us to gain insight to these mechanisms, however the models are limited by ethical standards and patients’ willingness to participate in clinical trials. Therefore, preclinical models are valuable in the process of uncovering molecular mechanisms and pathways involved in migraine pathophysiology. In this aspect, it is important that such models capture the disorder spectrum as closely as possible in terms of face validity, construct validity and predictive validity3,4.

The glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) mouse model of migraine has been used for more than a decade5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and is thus one of the most well-studied preclinical models of migraine. Nevertheless, the measurement outcome is most often tactile sensitivity to evoked stimuli using von Frey filaments or thermal heat and evaluating the withdrawal response13,14. This approach has its limitations. It is subjective and the investigator needs to be blinded to avoid observer-bias. Importantly, migraine patients mainly complain about non-evoked pain/headaches, even though fractions of patients also experience cutaneous allodynia15. Thus, preclinical models should also display non-evoked pain. Assessing non-evoked pain in mice, however, can be challenging as mice are prey animals and will repress signs of pain and discomfort to avoid attention from predator animals16,17.

Locomotor activity has been used as non-evoked pain assessment in several preclinical pain studies18,19,20,21. This approach is appealing due to the possibility of objectivity and often automated measuring systems, which reduces observer-bias and human errors. Likewise, burrowing and nest-building activities have also been used to assess pain16,22 and general rodent well-being17,23. Using the GTN mouse model, we aimed to investigate non-evoked behaviors as markers of pain and possibly the aggravation of pain by physical activity, experienced during migraine attacks. For this purpose, we used the Laboratory Animal Behaviour Observation Registration and Analysis System (LABORAS), which relays on spontaneous voluntary behaviour, and the burrowing assay, which relay on highly motivated, innate rodent behaviour23,24,25.

Methods

Animals

Mice were male and female C57Bl6/J BomTac purchased from Taconic (Denmark). Mice were group-housed (6–8 per cage) with food and water ad libitum and 12 L:12D schedule, lights on at 7 am. Further housing details were previously reported8. Experiments were planned and carried out in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All experiments included in this manuscript were in accordance with the European Community guide for the care and use of animals (2010/63/UE) and the study was approved and performed under license numbers 2017-15-0201-01358 and 2022-15-0201-01347 from the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate. An overview of experiments and mice is provided in Table 1. Note that in experiment 1, only female mice were included to avoid the risk of males fighting upon hours of isolation in test cages and return to home cages. No formal sample size calculation was performed as this was an explorative study and we had no realistic estimates of effect size and variation. Thus, group sizes were based on our previous experience with this model and behavioral readouts and were considered sufficient to provide a clear indication of the relevance of these behavioral readouts. Data from male and female mice were analyzed collectively as there are no previous reports of sex differences in this model. Accordingly, estrous cycle of the female mice was not monitored to keep the number of variables limited.

GTN model

The GTN-protocol followed that originally described by Pradhan and colleagues in which GTN is injected repeatedly on alternate days11. GTN (7.89 mg/mL in 96% ethanol (EtOH), Cambrex Germany, distributed via the Capital Region Hospital Pharmacy, Denmark) was diluted in isotonic saline (Fresenius Kabi, Germany) to 1 mg/mL and administered to mice at 10 mg/kg. The GTN vehicle consisted of corresponding amount of EtOH in saline (12.17% EtOH solution). For the LABORAS experiments, mice were dosed every other day for 11 days resulting in a total of 6 doses. An additional LABORAS test day (day 13) was included for half of the mice from experiment 1 (n = 8/group), resulting in a total of 7 doses for these mice. For burrowing, mice were injected a total of 3 times (days 1, 3, and 5).

Von Frey test

A detailed description of the procedure was made elsewhere7,26, but in short, mice were left in individual test cages (IITC Life Science, CA, USA) for acclimatation for approximately 45 min. Hind paw sensitivity was measured by stimulation with von Frey filaments (range 0.008–2.0 g (excluding 1.4 g), Ugo Basile, Italy) using the up-down method27. The response pattern was noted, and the 50% withdrawal threshold was calculated as described by Christensen et al.28. All von Frey tests were performed by an experimenter blinded to treatment group.

LABORAS setup

The LABORAS setup consisted of LABORAS test boxes resembling home cages (22 × 16 × 14 cm), situated on the LABORAS platforms connected to a computer and LABORAS software-v2.6.9 (Metris B.V, The Netherlands). Each LABORAS test cage was equipped with LABORAS water bottles and lids with a den for food pellets (see Fig. 1B). The floor was covered with standard saw dust bedding material. Each platform was calibrated as per manufacturer’s instructions prior to test using individual mouse body weights and the provided reference weight. The LABORAS setup was placed in a dedicated room in an isolated area of the animal facility. Light intensity was 30–40 lx, temperature 20–21 °C, and no people were present during testing. The standard LABORAS mouse behaviour package, which includes distance travelled, locomotion, climbing, grooming, rearing, immobility, drinking, eating and avg. speed. Data was retrieved in bins of 15 min unless otherwise stated.

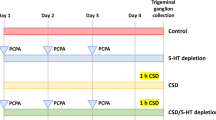

Schematic overview of experimental protocols and setup for each experiment. (A) Graphic illustration of timeline and study design for experiment 1–3. (B) Picture of LABORAS test cages. (C) Picture of burrowing tube in test cage. NB. Pictures do not represent the experimental light conditions. Created with BioRender.com.

LABORAS validation pilot study

To validate that our LABORAS setup could detect changes in behavior, we performed a small pilot study on 6 male mice, some slightly sedated with midazolam. 3 mice were injected with midazolam 2 mg/kg, i.p. (Hameln Pharma, Germany) diluted in saline to 0.2 mg/ml while the other 3 mice received saline injections. Mice were placed in the LABORAS test cages immediately after dosing and allowed to freely explore for 2 h with minimal disturbances. For this experiment, data were retrieved in 5 min bins.

Experiment 1 (LABORAS)

The aim was to explore different LABORAS test protocols to identify the ideal test scenario to pick up effects of GTN. Tactile and heat hypersensitivity peak 1–2 h after injection10 On day 1, mice were dosed with GTN or vehicle in the morning (approx. 9.30 am), placed into individual LABORAS test cages, and allowed to explore freely for 4 h with no disturbances. After end test, mice were returned to their respective home cages and left undisturbed until next test day. On day 3, mice were subjected to basal von Frey testing followed by dosing with GTN or vehicle and another von Frey test 2 h later. The basal von Frey (prior to dosing) was repeated on day 10 to confirm effectiveness of GTN-injections. On day 5, dosing and LABORAS test were performed according to day 1 protocol but was initiated in the evening to capture changes in locomotion during the animals’ active phase (dosing approx. 7 pm immediately followed by LABORAS test for 4 h). Dosing and LABORAS tests on day 7 and 9 were performed according to day 1 protocol. On day 11, mice were dosed with GTN or vehicle, but LABORAS test was initiated 90 min later to capture a potential effect on exploration at the time of documented peak of hypersensitivity11. Figure 1A shows a schematic overview of the experimental design.

Experiment 2 (LABORAS)

Here, we aimed to test mice fully sensitized to GTN but with complete novelty to the LABORAS test chamber. Mice were equally divided into GTN or vehicle treatment groups (n = 12/group) and subjected to the repeated GTN provocation protocol, as previously described7,26. Briefly, mice had von Frey test before and 2 h after GTN/vehicle injection on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. On day 11, mice had a sixth injection of GTN/vehicle and were placed in the LABORAS test cages 60 min after dosing and left undisturbed for 2 h (Fig. 1A) as an attempt to capture data around the peak GTN effect at 2 h10.

Experiment 3 (burrowing)

In experiment 3a, 10 female and 10 male mice were equally divided into GTN or vehicle groups (n = 10/groups) and subjected to the repeated GTN provocation + von Frey testing protocol as described above. After a 5-day washout period, mice were introduced to the burrowing protocol as previously described25,29 with slight alterations. GTN/vehicle was given days 1, 3, and 5. Acclimatization (training) to the burrowing tubes was performed overnight between day 4 and day 5 by placing a tube with food pellets in the home cages. On day 5 prior to dosing, mice were placed in individual cages, resembling home cages but only bedding and one burrowing tube filled with 270 g food pellets were present (see Fig. 1C). Mice were allowed to burrow for 30 min (basal) after which they were returned to their home cages and food pellets left in the tube was measured. Mice were then dosed with GTN, or vehicle and the burrowing assay was repeated after 1 h (Fig. 1A). In experiment 3b, the basal burrowing test was repeated with naïve mice (n = 10/group).

Statistics

All statistics were performed in GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA). LABORAS data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures while von Frey data were analyzed using mixed-effects model. For experiment 2 day 11, t-test was used to analyze locomotion and distance travelled. The first set of burrowing data (Exp. 3a) was analyzed using 2-way repeated measures ANOVA and the replication dataset (3b) was analyzed using t-test. When appropriate, Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used.

Results

Validation pilot study

Midazolam significantly reduced distance travelled (p = 0.037) and rearing (p = 0.024). Locomotion (p = 0.076) and immobility (p = 0.055) was also clearly affected by midazolam, albeit not significant with n = 3 (Fig. 2A-D). This pilot data clearly illustrates that the LABORAS setup is capable of picking up altered behavioral patterns induced by the sedating effect of midazolam.

Experiment 1 and experiment 2 (LABORAS)

As a positive control (to confirm GTN-induced hypersensitivity), von Frey test was performed on day 3 before (basal) and 2 h after GTN/vehicle administration and again on day 10 (basal) for Experiment 1. Mixed-effect analysis revealed significant effect of treatment (F1,85=74.44, p < 0.0001), non-significant effect of time (F2,85=2.063, p = 0.133) and a significant interaction time x treatment (F2,85=5.439 p = 0.006); see Fig. 3A. Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction, showed significant differences between vehicle and GTN groups at all timepoint (day 3 (basal): p = 0.048, day 3 (2 h): p < 0.0001, day 10 (basal): p < 0.0001).

Data summary from Experiment 1 and 2. A) Von Frey test was performed before (basal) and 2 h after i.p. injection of GTN 10 mg/kg or its vehicle, mixed effect model with Bonferroni post hoc comparison between groups, n = 16/group, individual values and mean ± SEM. B-D) 4 h LABORAS data obtained from same mice as in A on days 1, 5, 7, and 9 immediately after GTN injection. No effect of GTN, but increased activity when testing during the dark phase (day 5), day effect p < 0.0001, Two-way repeated ANOVA. E-F) Von Frey data days 1–9 before (basal) and 2 h after i.p. injection of GTN 10 mg/kg or its vehicle, mixed effect model with Bonferroni post hoc comparison between groups, n = 12/group, mean ± SEM. G-H) Locomotion and distance traveled on day 11 with a 60 min delay of LABORAS initiation after GTN injection. Same mice as in E-F, students t-test.

The primary readout for these experiments was locomotion. Here, 2-way repeated measure ANOVA revealed no effect of treatment (F1,30=7.205e− 5, p = 0.993; see Fig. 3B) or of the interaction effect of day x treatment (F4,120=0.596, p = 0.666) but a significant effect of day (F2.436,73.09=119.4, p < 0.0001). Likewise, for distance travelled, we found no effect of treatment (F1,30=0.1557, p = 0.696; see Fig. 3C) or for the interaction effect of day x treatment (F4,120=0.831, p = 0.508) but a significant effect of day (F2.326,69.78=132.5, p < 0.0001). On day 5, the LABORAS test was initiated in the first part of dark cycle, which likely drove the significant effect of day in the statistical analyses as mice were generally much more active during this test. Immobility time was also recorded and analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures. There was no significant effect of treatment (F1,30=0.717, p = 0.404; see Fig. 3D) or the interaction effect of day x treatment (F4,120=1.153, p = 0.335) but a significant effect of day (F3.363,100.9=213.6, p < 0.0001).

On day 11, mice were placed in LABORAS test cages 90 min after GTN/vehicle injection to investigate explorative behaviour during the time where the animals are most sensitive to von Frey stimulation (approx. 2 h after dosing11). However, we found no evidence of a GTN effect on day 11 on locomotion, distance travelled, or immobility. Noteworthily, these animals were familiar with the LABORAS test cages at this timepoint, which may have altered the exploratory behaviour. Therefore, we performed experiment 2 on mice naïve to LABORAS. Here, mice went through the repeated GTN provocation and von Frey tests day 1–9 (Fig. 3E-F). On Day 11, mice were dosed with GTN or vehicle and placed in LABORAS test cages 60 min later. However, this approach also did not capture an effect of GTN on locomotion or distance travelled (Fig. 3G-H).

The secondary readouts of these experiments were grooming, eating, drinking, avg. speed, rearing and climbing. Data for these parameters are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1. However, none of these datasets illustrated difference between GTN and vehicle treated mice.

Experiment 3 (burrowing)

We observed an indication of reduced burrowing behavior in GTN treated mice compared to vehicle treated mice on day 5 at the basal reading but no difference 1 h after dosing (Figs. 2 and 4A-way ANOVA; time F1,18=10.93, p = 0.003; treatment F1,18=2.936, p = 0.104; time x treatment F1,18=0.694, p = 0.416). To confirm the reduced burrowing behavior prior to dosing, we repeated the basal burrowing test in a naïve cohort of mice but found no difference between the groups (Fig. 4B; paired t-test p = 0.811).

Graphic illustration of the results of Experiment 3, burrowing. (A) First cohort of mice revealed a trend of reduced burrowing behaviour in GTN treated mice at the day 5 basal test (48 h after the 2nd injection) but this effect was lost when burrowing behaviour was measured 1 h after dosing on the same day. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 10/group, individual values and mean ± SEM. (B) In a naïve cohort of mice, the trend seen in A) could not be repeated. Students t-tests, n = 10/group, individual values and mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Preclinical models need to capture characteristics of the human symptom spectra as closely as possible to have relevance. In migraine research, animal models have aided in the pathophysiological understanding of pain pathways13. However, pain is a subjective experience and therefore measuring pain in rodents is difficult which is why changes in innate rodent spontaneous behaviour can be used as surrogate or additional markers of pain perception. Locomotor activity, immobility, rearing, drinking/eating and facial grimaces have been used as indicators of pain perception in preclinical models of migraine13 but with a lack of robustness and reproducibility across labs21,29,30. Researchers within the field of rodent pain models need to validate and improve their behavioral assays over time to keep up with new techniques, better equipment, automated software, and the demand for better translatability and relevance to clinical findings.

In this study, we wanted to investigate spontaneous behavioral manifestations as alternative readouts in the commonly used mouse model of GTN-induced migraine. Our study addresses aspects of evoked vs. non-evoked pain behavior. We focus on locomotor activity and burrowing behavior as potential additional markers of general pain or the aggravation of pain by physical activity, a characteristic symptom of migraine.

Using the LABORAS system, we found no difference in locomotor activity between GTN, and vehicle treated mice on any test day or with different timepoints of test initiation. It is unknown whether the GTN effect would be enhanced or masked by the excessive explorative behaviour expressed by mice when placed in a novel test chamber. Likewise, the higher activity level of mice during the dark phase may alter the detection of GTN induced behaviors. Thus, we tested multiple test scenarios to see if one was superior to the others, but also repeated the same scenario day 1, 7, and 9 to evaluate upon the repeated GTN sensitization protocol and habituation to the LABORAS test chambers. Sensitivity of the LABORAS technology was confirmed by the pilot study and by the detection of diurnal differences in mouse activity levels.

Other studies have shown that multiple doses of GTN reduces locomotor activity in rats21,31. Interestingly, vehicle (30% propylene glycol and 30% ethanol) treated animals had similar reduced locomotor activity and distance travelled as GTN treated animals, both of which differed from saline treated animals31. One study showed that ethanol in a concentration of 16% (10 ml/kg volume) increased locomotor activity but decreased locomotor activity at 32% 35. In our study, both GTN and vehicle contained 12.17% ethanol injected in a volume of 10 ml/kg. We cannot rule out that the ethanol increased locomotor activity in our setup. Explorative comparison of saline treated mice from our validation pilot study to vehicle treated mice from experiment 1, revealed a significantly higher locomotor response in vehicle mice than in saline treated mice (p = 0.0016, Supplementary Fig. S2). It is reasonable to speculate that the high amount of ethanol in the vehicle and GTN solution may have masked any possible effect of GTN on locomotion in our experiments. The vehicle of various GTN formulations is often debated3,30 and the lack of import/export options for GTN makes it hard to directly compare GTN experiments across countries. Notably, burrowing was performed when no alcohol confounding was present and yet no effect of GTN was found.

The LABORAS system has been used to evaluate non-evoked pain behaviour in mice. Hasriadi and colleagues showed that an inflammatory agent introduced into the paw significantly reduced locomotor behaviour in the LABORAS test cages, which could be reversed by NSAID treatment, and that this effect correlated positively with reduced threshold values in the von Frey assay18. Another study was unable to find any significant effects in a surgical mouse model of osteoarthritis but found significantly reduced grooming behaviour and significantly increased immobility in a collagen-induced arthritis mouse model, which relies on inflammation19. Here, the authors argued that the LABORAS may be a good tool for assessing inflammatory-related pain but less sensitive to other types of pain. It is worth mentioning that evaluating inflammatory pain using non-evoked stimuli should consider the potential confounding effect of general illness because of the inflammatory agent. Thus, such studies could advantageously also include observations like weight changes, eating/drinking behaviour and/or evoked pain assessments.

Other groups have found reduced locomotion in rodent models of migraine, like single injection of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and LABORAS/wheel running33, multiple injections of GTN and open field test20,34 or single injection of allyl isothiocyanate to the dura and home cage wheel running35. The diversity in experimental setups, illustrates that the search for an assay to capture reduced locomotion in rodent migraine models is not straight forward. This may explain why there is no consensus in the preclinical migraine field on one behavioral non-evoked pain assay. In the above-mentioned studies rats were used rather than mice and in terms of behavioral assay mice and rats may respond differently36.

We observed a non-significant reduction in burrowing behavior 48 h after the 2nd injection of GTN, but the effect was lost when re-testing 1 h after the third dose. Two reasons may explain this. First, GTN and vehicle contains 12.17% ethanol, which as mentioned previously might have increased mouse activity at the 1 h time point. Second, mice improve their burrowing behavior with training25, which explains why we found that both GTN and vehicle mice burrowed more during the second burrowing test than the first test. We were unable to replicate the decreased burrowing activity in a new cohort of mice and conclude that burrowing behaviour is not altered at basal day 5.

One point of improvement in our burrowing setup is time. None of the mice emptied the burrowing tubes completely, which means we avoided the possible ceiling effect of this assay by allowing burrowing for 30 min. Contrary, it might have been too long to observe a difference between the groups. One study argued for a 15 min test window, as most burrowing was performed during the first 15 min37. The effect window of GTN may have been clearer with a shorter test duration. As we were unable to replicate the tendency found in our first experiment, it questions the value of the burrowing assay in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Previous studies in our group in rats29 and others in mice37 have come to similar conclusions in terms of burrowing and the GTN model.

Different responses to stimulation with GTN have been described in both humans and animals. People with migraine generally get migraine attacks following GTN infusion whereas people without a history of migraine only experience a mild transient headache38. However, there are exceptions, as people suffering from familial hemiplegic migraine types 1 and 2 do not develop migraine attacks after GTN infusions39,40. Genetic variation in rodents is also well known as e.g., mutations in casein-kinase 1 delta leads to increased sensitivity to GTN in mice41 and in rats the spontaneous trigeminal allodynia model displayed a hereditary hypersensitivity to migraine triggers42. We chose the repeated GTN sensitization protocol in wild type mice established by Pradhan and colleagues11 as the effects are well described and hence suitable for screening of potentially new migraine assays. It is yet a translational mystery why wild type mice respond with pronounced tactile and heat hypersensitivity to GTN after a single dose10. Studies on physiological responses to GTN in mice are needed and should be correlated to behavioral endpoints as well as human physiological data e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, cranial arterial dilation for improved translational understanding of the model.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this explorative study is the repeated testing of the same mouse cohort to evaluate different test paradigm in a relatively large cohort. Importantly, von Frey testing was performed as a positive control for GTN efficiency. For burrowing, the replication study was important to test if the observed small effect in the first experiment was real or random. The study also has some limitations worth noting. Given the variability in spontaneous behaviour of mice, there is a risk that our experiments may have been underpowered to pick up small effects in the LABORAS system and burrowing assay. It is possible that with a higher number of animals the LABORAS and/or burrowing assay could be used to understand non-pain behaviour in a migraine mouse model. However, this scenario is unlikely as we did not see indications of even a small effect on locomotion activity using 16 animals per group. Thus, we are reluctant to pursue further experiments with this setup. Other technologies may be able to detect GTN induced non-evoked changes.

Conclusion

We conclude that burrowing and locomotor activity, objectively scored via LABORAS, are not valid behavioral assays of migraine-like pain in GTN-induced mouse model of migraine. Thus, the search for non-evoked mouse behaviors that can be readily detected, automated, and reproduced across laboratories needs to continue.

Data availability

All data used for these studies can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- EtOH:

-

Ethanol

- GTN:

-

Glyceryl trinitrate

- I.p.:

-

Intraperitoneal

- LABORAS:

-

Laboratory Animal Behaviour Observation Registration and Analysis System

References

Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J., Jensen, R., Uluduz, D. & Katsarava, Z. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J. Headache Pain. 21, 4–7 (2020).

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia vol. 38 1–211 (2018).

Olesen, J. & Jansen-Olesen, I. Towards a reliable animal model of migraine. Cephalalgia. 32, 578–580 (2012).

Storer, R. J., Supronsinchai, W. & Srikiatkhachorn, A. Animal models of chronic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 19, (2015).

Christensen, S. L. et al. Smooth muscle ATP-sensitive potassium channels mediate migraine-relevant hypersensitivity in mouse models. Cephalalgia. 42, 93–107 (2022).

Christensen, S. L., Ernstsen, C., Olesen, J. & Kristensen, D. M. No central action of CGRP antagonising drugs in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Cephalalgia. 40, 924–934 (2020).

Christensen, S. L. et al. CGRP-dependent signalling pathways involved in mouse models of GTN- cilostazol- and levcromakalim-induced migraine. Cephalalgia. 41, 1413–1426 (2021).

Ernstsen, C., Christensen, S. L., Olesen, J. & Kristensen, D. M. No additive effect of combining sumatriptan and olcegepant in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Cephalalgia. 41, 329–339 (2021).

Tipton, A. F., Tarash, I., McGuire, B., Charles, A. & Pradhan, A. A. The effects of acute and preventive migraine therapies in a mouse model of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 36, 1048–1056 (2016).

Bates, E. A. et al. Sumatriptan alleviates nitroglycerin-induced mechanical and thermal allodynia in mice. Cephalalgia. 30, 170–178 (2010).

Pradhan, A. A. et al. Characterization of a novel model of chronic migraine. Pain. 155, 269–274 (2014).

Moye, L. S. & Pradhan, A. A. Animal Model of Chronic Migraine-Associated Pain. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 80, (2017). 9.60.1–9.60.9.

Vuralli, D., Wattiez, A. S., Russo, A. F. & Bolay, H. Behavioral and cognitive animal models in headache research. J. Headache Pain 20, (2019).

Harriott, A. M., Strother, L. C., Vila-Pueyo, M. & Holland, P. R. Animal models of migraine and experimental techniques used to examine trigeminal sensory processing. J. Headache Pain 20, (2019).

Burstein, R., Yarnitsky, D., Goor-Aryeh, I., Ransil, B. J. & Bajwa, Z. H. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann. Neurol. 47, 614–624 (2000).

Jirkof, P. et al. Burrowing behavior as an indicator of post-laparotomy pain in mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 4, 1–9 (2010).

Turner, P. V., Pang, D. S. J. & Lofgren, J. L. S. A review of pain assessment methods in laboratory rodents. Comp. Med. 69, 451–467 (2019).

Hasriadi, Wasana, P. W. D., Vajragupta, O., Rojsitthisak, P. & Towiwat, P. Automated home-cage for the evaluation of innate non-reflexive pain behaviors in a mouse model of inflammatory pain. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–16 (2021).

von Loga, I. S. et al. Comparison of LABORAS with static incapacitance testing for assessing spontaneous pain behaviour in surgically-induced murine osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open. 2, 100101 (2020).

Demartini, C., Greco, R., Francavilla, M., Zanaboni, A. M. & Tassorelli, C. Modelling migraine-related features in the nitroglycerin animal model: trigeminal hyperalgesia is associated with affective status and motor behavior. Physiol. Behav. 256, 113956 (2022).

Sufka, K. J. et al. Clinically relevant behavioral endpoints in a recurrent nitroglycerin migraine model in rats. J. Headache Pain 17, (2016).

Gjendal, K., Ottesen, J. L., Olsson, I. A. S. & Sørensen, D. B. Burrowing and nest building activity in mice after exposure to grid floor, isoflurane or ip injections. Physiol. Behav. 206, 59–66 (2019).

Jirkof, P. Burrowing and nest building behavior as indicators of well-being in mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 234, 139–146 (2014).

Deacon, R. M. J. & Burrowing A sensitive behavioural assay, tested in five species of laboratory rodents. Behav. Brain. Res. 200, 128–133 (2009).

Deacon, R. M. J. Burrowing in rodents: A sensitive method for detecting behavioral dysfunction. Nat. Protoc. 1, 118–121 (2006).

Christensen, S. L. et al. ATP sensitive potassium (KATP) channel inhibition: A promising new drug target for migraine. Cephalalgia. 40, 650–664 (2020).

Mills, C. et al. Estimating efficacy and drug ED 50’s using Von frey thresholds: Impact of Weber’s Law and log transformation. J. Pain. 13, 519–523 (2012).

Christensen, S. L. et al. Von Frey testing revisited: Provision of an online algorithm for improved accuracy of 50% thresholds. Eur. J. Pain. 24, 783–790 (2020).

Christensen, S. L., Petersen, S., Sørensen, D. B., Olesen, J. & Jansen-Olesen, I. Infusion of low dose glyceryl trinitrate has no consistent effect on burrowing behavior, running wheel activity and light sensitivity in female rats. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 80, 43–50 (2016).

Farkas, S. et al. Utility of different outcome measures for the nitroglycerin model of migraine in mice. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 77, 33–44 (2016).

Harris, H. M., Carpenter, J. M., Black, J. R., Smitherman, T. A. & Sufka, K. J. The effects of repeated nitroglycerin administrations in rats; modeling migraine-related endpoints and chronification. J. Neurosci. Methods. 284, 63–70 (2017).

Castro, C. A., Hogan, J. B., Benson, K. A., Shehata, C. W. & Landauer, M. R. Behavioral effects of vehicles: DMSO, ethanol, Tween-20, Tween-80, and emulphor-620. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 50, 521–526 (1995).

Wattiez, A. S. et al. CGRP induces migraine-like symptoms in mice during both the active and inactive phases. J. Headache Pain. 22, 1–13 (2021).

Taheri, P. et al. Nitric oxide role in anxiety-like behavior, memory and cognitive impairments in animal model of chronic migraine. Heliyon. 6, e05654 (2020).

Kandasamy, R., Lee, A. T. & Morgan, M. M. Depression of home cage wheel running: a reliable and clinically relevant method to assess migraine pain in rats. J. Headache Pain. 18, 1–8 (2017).

Ellenbroek, B. & Youn, J. Rodent models in neuroscience research: is it a rat race? DMM Disease Models Mech. 9, 1079–1087 (2016).

Shepherd, A. J., Cloud, M. E., Cao, Y. Q. & Mohapatra, D. P. Deficits in burrowing behaviors are associated with mouse models of neuropathic but not inflammatory pain or migraine. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, (2018).

Thomsen, L. L., Kruuse, C., Iversen, H. K. & Olesen, J. A nitric oxide donor (nitroglycerin) triggers genuine migraine attacks. Eur. J. Neurol. 1, 73–80 (1994).

Hansen, J. M., Thomsen, L. L., Olesen, J. & Ashina, M. Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 shows no hypersensitivity to nitric oxide. Cephalalgia. 28, 496–505 (2008).

Hansen, J. M. et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine type 2 does not share hypersensitivity to nitric oxide with common types of migraine. Cephalalgia. 28, 367–375 (2008).

Brennan, K. C. et al. Casein kinase iδ mutations in familial migraine and advanced sleep phase. Sci. Transl Med. 5, (2013).

Oshinsky, M. L. et al. Spontaneous trigeminal allodynia in rats: a model of primary headache. Headache. 52, 1336–1349 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express a special thanks to Prof. Jes Olesen for guidance during the experimental work and to Prof. David M Kristensen for letting experiments being performed under his license (2017-15-0201-01358).

Funding

These experiments were supported by Candys Foundation and Foreningen til støtte af Forskningen ved Dansk Hovedpine Center. Metris provided a free trial period of LABORAS software for mouse behavior.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC and SLC conceptualized the study design and performed experiment 1. KO-R performed the injections and von Frey assays of experiment 2, while AC and SLC performed the LABORAS assays. CLD-A performed the injections of experiment 3, while AC performed the burrowing assay. AC performed all data analyzes while interpretation was made by both AC and SLC. AC drafted the manuscript. KO-R drafted the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All experiments included in this manuscript were in accordance with the European Community guide for the care and use of animals (2010/63/UE) and the study was approved and performed under license numbers 2017-15-0201-01358 and 2022-15-0201-01347 from the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate. No patients/persons were used in these studies and thus consent to participate is not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clement, A., Dam-Amby, C.L., Obelitz-Ryom, K. et al. The search for non-evoked markers of pain in the GTN mouse model of migraine. Sci Rep 14, 26481 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78332-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78332-3