Abstract

The efficacy of diversion ileostomy followed by radical surgery for locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer remains uncertain. This study seeks to compare the effectiveness of treatment with and without diversion ileostomy in preventing anastomotic leakage (AL) and to identify a subset who may benefit from diversion ileostomy after AL occurs in Chinese patients with stage II and III upper-half rectal cancer. A retrospective study enrolled a total of 809 patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer between 2017 and 2021, with 27.6% (n = 223) treated with diversion ileostomy and 72.4% (n = 586) treated without diversion ileostomy. The Diversion(+) group (n = 172) and Diversion(−) group (n = 172) were compared for perioperative outcomes through 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM). The selection of variables for multivariable logistic regression was determined through bivariate logistic regression analysis. Additionally, optimal cutoff values for risk factors were identified using ROC curve analysis. Within the entire cohort, patients in the Diversion(+) group exhibited a lower distance from the anal verge (DAV) and higher rates of chemoradiotherapy (CRT), diabetes, cN2 stage, mrCRM positivity, EMVI positivity, and CEA elevation compared to those in the Diversion(−) group. Following PSM, a satisfactory balance of baseline variables was achieved between the two groups. There were no statistically significant differences in AL rates (7.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.659) or AL grade distribution (Grade A: 0.6% vs. 0%, Grade B: 5.2% vs. 4.1%, Grade C: 1.2% vs. 1.7%, p = 0.691) between the two groups. However, the Diversion(+) group demonstrated a higher incidence of postoperative complications (30.8% vs. 17.4%, p = 0.004), Clavien‒Dindo III–IV complications (2.9% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.013), particularly wound infections (8.1% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.002), and early postoperative inflammatory small bowel obstruction (EPISBO) (8.7% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.001) compared to the Diversion(−) group. Results from multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that male gender (OR = 2.354, p = 0.014) was the only independent risk factor associated with AL, while the presence of diversion ileostomy (with vs. without, OR = 1.144, p = 0.686) did not show significant associations. In patients with AL, the onset of the AL was observed to occur later in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group (7.0 ± 3.3 vs. 3.4 ± 1.4 days, p < 0.001), while the recovery time was significantly shorter (11.3 ± 4.7 vs. 20.3 ± 7.2 days, p < 0.001). Similarly, in Grade C AL patients, the occurence time was delayed in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group (8.7 ± 4.7 vs. 3.2 ± 1.5 days, p = 0.008), with a shorter recovery time (19.3 ± 2.1 vs. 25.7 ± 6.7 days, p = 0.031). A trend was observed indicating a longer interval before ileostomy restoration in the AL patients compared to the non-AL patients (7.6 ± 4.9 months vs. 5.5 ± 2.9 months, p = 0.079). In addition, DAV (OR = 0.078, p = 0.002) was identified as the only independent factor associated with potential-diversion-benefit in patients with AL, with an optimal cutoff point of 8.6 cm. The utilization of diversion ileostomy as a preventative measure for AL in cases of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer is not universally endorsed due to potential complications such as small bowel obstruction and wound infection. Nevertheless, in the occurrence of AL, diversion ileostomy may prove advantageous for patient recuperation. Particularly, male patients with a DAV ranging from 7 to 8.6 cm may experience benefits from undergoing diversion ileostomy subsequent to AL in cases of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anastomotic leakage (AL) is a prevalent and significant complication following anterior resection of rectal tumors, with reported incidence rates ranging from 2.4 to 15.9%, and associated morbidity and mortality rates as high as 16%1. In recent years, following anterior resection for rectal cancer, the implementation of a diversion ileostomy has been proposed as potentially advantageous in mitigating the risk of anastomotic leakage. However, the applicability and efficacy of this approach across all tumor sites of rectal cancer remains a topic of debate2,3,4,5,6,7. Recent studies have shown that diversion ileostomy may not improve short-term outcomes in patients undergoing rectal resection, but may increase operation complications4,7. Conversely, other studies have demonstrated that diversion ileostomy is effective in preventing AL following rectal cancer surgery or in mitigating the clinical manifestations associated with AL2,3,5,6. The inconsistencies in these findings may be attributed to various factors, such as the lack of subgroup analysis in some studies that included patients with rectal cancer in all locations, thereby limiting the reference value of the conclusions. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies investigating the risk factors associated with anastomotic fistula, making it unreasonable to universally recommend diversion ileostomy for all patients without individualized assessment. Additionally, the complexity of interpreting the aforementioned findings and drawing conclusions is compounded by the inclusion of rectal cancer patients at varying clinical stages, inconsistent surgical techniques, and diverse approaches to diversion stoma placement.

According to ESMO guidelines8, rectal cancers are classified as lower third (≤ 5.0 cm from the anal verge), mid third (> 5–10 cm), or upper third (> 10–15 cm). However, according to the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) and the Korean Society of Abdominal Radiology (KSAR), the utilization of these terminologies for characterizing the position of a rectal cancer is not advisable. Instead, it is recommended to employ the association of a rectal cancer with the anterior peritoneal reflection (APR), a distinguishable landmark on MRI that demarcates the intra- and extra-peritoneal segments of the mesorectal compartment9,10. A recent study conducted in Korea defined upper rectal cancers as those situated above the APR, determined by drawing an imaginary line extending perpendicularly from the peritoneal reflection to the rectal tube, as indicated by MRI11. In comparison to the rectum located above the APR, the rectum situated below this anatomical landmark exhibits diminished vascular complexes within the rectal mesentery, as well as a limited and unstable number of intramural collaterals, and consequently, this may account for the elevated incidence of AL in cases of low rectal cancer below APR12. As a result, there is a growing consensus regarding the necessity of implementing proactive and targeted protective measures, such as selective diversion ileostomy, in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for low rectal cancer, particularly in the presence of identified high-risk factors for AL. However, considering the fact that the APR is typically situated approximately 7 cm from the anal verge, the applicability of this selective diversion ileostomy measurement to patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer located above the APR, particularly tumors positioned 7–15 cm from the anal verge as identified by MRI, remains a topic of controversy with limited documentation. Consequently, our research encompassed individuals diagnosed with stage II/III rectal cancer located 7–15 cm from the anal verge. We present findings from our institution regarding the management of patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer, both with and without diversion ileostomy, in terms of perioperative oncologic outcomes. Our aim is to ascertain the necessity of diversion ileostomy in this patient cohort, as well as its potential benefits in aiding the recovery of patients with AL.

Patients and methods

Study population

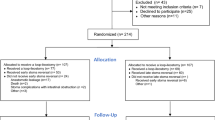

This retrospective, monocentric study utilized data from a prospectively maintained colorectal cancer database to analyze 809 patients who underwent radical surgery for locally advanced upper-half rectal cacer at the Department of Colorectal Surgery of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Fuzhou, China) between 2017 and 2021. The inclusion criteria for the study consisted of patients with histologically confirmed rectal carcinoma, rectal tumors located 7–15 cm from the anal verge as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinically staged as cT3-4Nx or cTxN + rectal tumors assessed by MRI, and who underwent treatment with diversion ileostomy followed by radical surgery (Diversion(+) group) or without diversion ileostomy (Diversion(−) group). Inclusion criteria included distant metastases at diagnosis, synchronous malignancy, or a history of another malignant tumor, emergency surgery, or palliative surgery. This study was sanctioned by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital and adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective design of the study, the IRB of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital exempted the requirement for informed consent. The personal data of the participants in the study were de-identified to ensure anonymity.

Treatment and pathology results

Multi-Disciplinary Treatment (MDT) program was implemented to assess the suitability of preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for patients diagnosed with locally advanced rectal cancer. Following the completion of radiotherapy, radical surgery was scheduled to take place 6–8 weeks later. Surgical resection adhered to the principles of total mesorectal excision (TME) or partial mesorectal excision (PME) for the entire cohort patients. Inadequate mechanical anastomosis was detected through the air leak test, prompting the consideration of diversion ileostomy based on factors such as the patient’s overall health, nutritional status, diabetes, and distance from the anal verge (DAV). Tumor staging was conducted utilizing the TNM classification as outlined in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC), with the presence of perineural invasion (PNI) and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) documented in the pathology report.

Definitions

The study utilized the international Clavien classification to categorize 90-day postoperative complications, with major morbidity defined as events necessitating endoscopic, radiological, or surgical reoperation or intensive care unit treatment (Clavien‒Dindo grades III–IV), and minor morbidity defined as Clavien‒Dindo grades I–II13. AL was graded according to their clinical severity. Grade A indicated subclinical AL (also known as imaging AL) without clinical symptoms. Grade B was characterized by abdominal pain, fever, and purulent or fecal-like discharge from the anus, drainage tube, or vagina, along with an increased white blood cell count and C-reactive protein. Grade C was characterized by peritonitis, sepsis, and other clinical manifestations of Grade B requiring a secondary surgery. Occurrence time of AL was defined as the interval between the primary operation and the onset of AL, while the recovery time was defined as the length of hospitalization between AL occurrence and recovery. AL patients who underwent a diverting ileostomy at the time of primary surgery were categorized as the potential-diversion-benefit population, while those who did not undergo a diverting ileostomy were classified as the no-potential-diversion-benefit population. Overall survival (OS) was delineated as the duration from the initial diagnosis of rectal cancer to either death from any cause or the last follow-up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was characterized as the interval from the diagnosis of rectal cancer to either death, evidence of local recurrence, or distant metastasis.

Follow-up

Follow-up evaluations were conducted every 3 months for the first 3 years, then every 6 months for 2 years, and annually thereafter. Each visit included a physical exam, CEA test, chest X-ray or CT scan, and abdominal pelvic MRI or CT scan. Colonoscopy was done annually post-surgery, with PET-CT scans added as necessary. Follow-ups were done in person or remotely via phone, mail, or letter. The last follow-up was completed in November 2022.

Statistical analysis

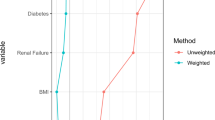

Statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS INC., Chicago), while GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was employed to generate graphs. Propensity score analysis was conducted using R to address baseline confounders between groups. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed through logistic regression modeling for each patient, with covariates including gender, age, CRT, DAV, diabetes, cT, cN, mrCRM, EMVI, and CEA, and CA199. One-to-one matching without replacement was conducted utilizing a 0.002 caliper width. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, while normally distributed data were analyzed with Student’s t tests. Nonnormally distributed data were analyzed with the Mann‒Whitney U test. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify independent risk factors for AL and potential-diversion-benefit. Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan‒Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. ROC curve was used to determine the optimal cutoff point of independent continuous variables. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient population

A total of 809 patients were enrolled in the study, including 513 (63.4%) males and 296 (36.6%) females. The participants’ mean age was 61.0 ± 11.1 years, and DAV was 9.6 ± 1.9 cm. Overall, 223 (27.6%) patients received diversion ileostomy and 586 (72.4%) patients did not receive diversion ileostomy followed by radical resection in the upper-half rectal cacer (7–15 cm from the anal verge, located near or above the APR).

Baseline characteristics

The demographic and clinical baseline characteristics of the unmatched and matched populations are summarized in Table 1. Prior to PSM, in the entire cohort, there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to gender, age, clinical T stage and CA-199 levels. A trend of lower DAV (8.4 ± 1.4 vs. 10.0 ± 2.0 cm) was found in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group (p < 0.001). The results indicate that the Diversion(+) group had higher rates of CRT patients (58.9% vs. 25.4%, p < 0.001), diabetic patients (19.7% vs. 11.9%, p = 0.004), cN2 (66.4% vs. 53.2%, p = 0.003), mrCRM positivity (35.9% vs. 20.3%, p < 0.001), EMVI positivity (65.5% vs. 51.9%, p = 0.001), CEA elevation (47.1% vs. 38.7%, p = 0.031).

After 1:1 PSM, both the Diversion(+) and Diversion(−) groups consisted of 172 patients each. It is evident that a satisfactory equilibrium of various variables, such as gender, age, CRT, DAV, diabete, cT, cN, mrCRM, EMVI, CEA, and CA199 levels, was achieved between the two groups.

Intraoperative parameters and short-term postoperative outcomes

As shown in Table 2, before PSM, there were no significant differences in AL rates (7.6% vs. 6.3%, p = 0.505) and AL grade distribution (Grade A (0.9% vs. 0.2%), Grade B (5.4% vs. 4.6%), Grade C (1.3% vs. 1.5%), p = 0.463) between the two groups. However, there was a higher proportion of employed procedures of robotic surgery (11.2% vs. 7.8%, p = 0.011) and convertion to laparotomy (1.8% vs. 0.2%, p = 0.022), postoperative complications (29.6% vs. 17.7%, p < 0.001) and Clavien‒Dindo III–IV (2.7% vs. 1.5%, p = 0.001), hospital stay days (18.5 ± 12.0 vs. 15.9 ± 9.1, p = 0.001), and surgery costs (1432.6 ± 86.7 vs. 1243.9 ± 38.1$, p = 0.021) in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group. After PSM, there were also no statistically significant differences in AL rates (7.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.659) and AL grade distribution (Grade A (0.6% vs. 0%), Grade B (5.2% vs. 4.1%), Grade C (1.2% vs. 1.7%), p = 0.691) between the two groups. However, the Diversion(+) group exhibited higher postoperative complications (30.8% vs. 17.4%, p = 0.004), Clavien‒Dindo III–IV (2.9% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.013), especially wound infection (8.1% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.002), early postoperative inflammatory small bowel obstruction (EPISBO) (8.7% vs. 1.2%, p = 0.001) compared to the Diversion(−) group. Additionally, there were no significant differences in operative method, anastomotic stenosis, anastomotic bleeding, postoperative sepsis, pneumonia, urinary infection, ICU stay requirements, hospital stay days and surgery costs between the two groups. Interestingly, the Diversion(+) group exhibited lower chylous leakage (1 (0.6%) vs. 8 (4.7%), p = 0.037) compared to the Diversion(−) group.

Predictive factors of anastomotic leakage (AL)

In the entire cohort, a total of 18 variables were assessed both pre- and postoperatively. Univariate analysis revealed that, in comparison to the Non-AL group (n = 755), the AL group (n = 54) exhibited a greater percentage of male patients (79.6% vs. 62.3%, p = 0.010) and a trend towards a higher proportion of diabetic patients (22.2% vs. 13.5%, p = 0.075). Conversely, variables including age, CRT, DAV, diversion, cT, cN, mrCRM, mrEMVI, CEA, CA-199, TNM stage, tumor diffferention, histopathology, PNI, LVI, harvested lymph nodes did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between the two groups. (Table 3)

Based on both clinical experience and the findings of the univariate analysis, we incorporated four variables - gender, DAV, diabete, and diversion - into the multivariate logistic regression model. The results indicated that male gender (OR = 2.354, p = 0.014) emerged as the sole independent risk factor associated with AL, while the variables of DAV (OR = 1.004, p = 0.963), diabete (with vs. without, OR = 1.782, p = 0.099), and diversion (with vs. without, OR = 1.144, p = 0.686) did not demonstrate significant associations.(Table 3).

Long-term oncologic outcomes of AL and Non-AL patients

The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 30.5 months (range, 6–63 months). Analysis of the data presented in Fig. 1 revealed no statistically significant differences in the 3-year overall survival (OS) rates (91.7% vs. 92.4%, p = 0.676, Fig. 1A) and 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates (81.4% vs. 84.7%, p = 0.749, Fig. 1B) between the AL group and the Non-AL group.

Time evaluation of AL patients

As shown in Table 4, within the entire cohort, 54 patients were identified with AL, representing 6.7% of the total cohort (54/809). Among these patients with AL, the onset of AL occurred significantly later in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group (7.0 ± 3.3 vs. 3.4 ± 1.4 days, p < 0.001), while the recovery time was significantly shorter (11.3 ± 4.7 vs. 20.3 ± 7.2 days, p < 0.001). In Grade C AL patients, the occurence time was also significantly delayed in the Diversion(+) group compared to the Diversion(−) group (8.7 ± 4.7 vs. 3.2 ± 1.5 days, p = 0.008), with a shorter recovery time (19.3 ± 2.1 vs. 25.7 ± 6.7 days, p = 0.031).

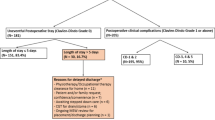

Time interval to ileostomy restoration

Diversion(+) group was categorized into two subgroups: AL group (17 patients) and Non-AL group (206 patients). It was observed that a significantly higher proportion of patients in the non-AL group underwent ileostomy restoration compared to those in the AL group (96.6% vs. 70.6%, p = 0.002). A trend was observed indicating a longer interval before ileostomy restoration in the AL group compared to the non-AL group (7.6 ± 4.9 months vs. 5.5 ± 2.9 months, p = 0.079). It is noteworthy that among patients who did not receive a diversion ileostomy during the initial surgery, nine subsequently required additional diverting stomas following the development of AL. For those who did undergo restoration surgery, the mean time interval was 8.7 ± 5.3 months (Table 5).

Predictive factors of potential-diversion-benefit

Only factors that were available prior to primary radical surgery were included analysis to identify candidate patients who might benefit from diversion ileostomy following AL, as defined by potential-diversion-benefit. In the AL cohort, lower DAV (7.6 ± 0.6 vs. 10.5 ± 1.8 cm, p < 0.001), a trend towards a higher proportion of mrCRM+ (41.2% vs. 18.9%, p = 0.083) and mrEMVI+ (76.5% vs. 51.4%, p = 0.081) were found by univariate analysis in the potential-diversion-benefit group (17 patients) compared to the no-potential-diversion-benefit group (37 patients). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that DAV (OR = 0.078, p = 0.002) was the only independent factor associated with potential-diversion-benefit (Table 6). Acoording to the ROC curve and maximal Youden-index, the optimal cutoff point of DAV was 8.6 cm (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Above the APR in the rectum, a robust collateral blood supply exists between small arteries within the mesentery, conversely, below the APR, there are limited and inconsistent intramural collateral branches between small arteries12. Failure to recognize and preserve the side branches of these small arteries during rectal resection may lead to an increased risk of AL. Although scholars have increasingly come to a consensus that patients with lower rectal cancer below the APR and high risk factors for AL should undergo careful evaluation during surgical exploration to determine their suitability for prophylactic ileostomy. However, for patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer above the APR, diversion ileostomy may also be considered in clinical practice to mitigate the risk of AL and associated complications. There is limited literature available regarding the efficacy of diversion ileostomy in patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer in terms of perioperative outcomes. Therefore, our study aimed to compare the effectiveness of treatment with and without diversion ileostomy in preventing AL and to identify a subset who may benefit from diversion ileostomy following AL in Chinese patients with stage II and III upper-half rectal cancer.

In our larger single-center retrospective study, 809 patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer were included, with 27.6% undergoing diversion ileostomy after radical surgery and 72.4% not undergoing. Our study revealed that surgeons frequently opt to perform diversion ileostomy in patients with lower DAV, those undergoing CRT, and those with comorbid diabetes mellitus in upper-half rectal cancers. Additionally, patients who underwent diversion ileostomy displayed more advanced clinical tumor staging and a more invasive phenotype. Surgeons also showed a preference for performing a diverting ileostomy in patients undergoing robotic surgery and conversion to laparotomy. Furthermore, the implementation of diversion ileostomy did not lead to a decrease in the occurrence of AL, but rather resulted in increased complications, extended hospital stays, and higher expenses.

However, it is important to note that the findings were not adjusted for potential confounding variables related to baseline characteristics that could impact short-term postoperative outcomes. Therefore, a case matching approach was utilized in the current study to address and control for these variables. Following PSM, the results similarly indicated that diversion ileostomy did not significantly reduce the incidence of AL (7.0% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.659) or impact the occurrence of varying grades of AL. Conversely, it was associated with an increased incidence of postoperative wound infection (8.1% vs. 1.2%) and EPISBO (8.7% vs. 1.2%). It was documented that a majority of patients with a diversion stoma commonly experience peristomal skin complications, such as skin irritation and infection, typically occurring 21–40 days after diversion creation14. Akesson O et al. reported that during diversion reversal, approximately 40% of patients experience surgical complications, most commonly small bowel obstruction and wound sepsis15. Interestingly, plasma Butyrylcholinesterase level, a cost-effective and readily accessible laboratory marker, has been reported to predict the risk of postoperative complications, particularly surgical site infections, and a decrease in Butyrylcholinesterase levels on the first and third days following colorectal surgery has been associated with an increased risk of such infections16. In our institution, ileostomies were typically placed at the longitudinal skin incision rather than a separate circular incision, potentially contributing to wound infections. In future research, we aim to identify patients with diversion ileostomy who are at risk of surgical incision infections by measuring postoperative butyrylcholinesterase levels. This will enable us to implement preemptive interventions to prevent these complications. Our study suggested that for locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer, the use of diversion ileostomy might not be advisable for reducing the incidence of AL due to the inherent drawbacks associated with ileostomy placement. Furthermore, these findings were substantiated through multifactorial logistic regression analysis, which indicated that diversion ileostomy did not pose as an independent risk factor for AL in locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer. The analysis revealed that male gender (OR = 2.354, p = 0.014) was identified as an independent risk factor for AL. This observation aligned with previous studies that had suggested a higher incidence of AL in male individuals, potentially attributed to technical challenges posed by pelvic stenosis following low anterior resection for rectal cancer17,18. Numerous factors have been identified as potential risk factors for AL, including male gender, obesity, hypoalbuminemia, malnutrition, anemia, weight loss, low anastomosis, preoperative CRT, intraoperative complications, and prolonged operative duration19,20,21,22. However, our study focusing on locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer found that CRT was not associated with an increased risk of AL. Furthermore, previous research indicated that chemoradiotherapy should not be routinely recommended for the treatment of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer due to its lack of improvement in long-term oncologic outcomes23.

There is widespread consensus that AL results in a negative prognosis for local recurrence following rectal resection24. Warrier et al. reported that AL was associated with local recurrence (OR = 1.61), but not distant recurrence (OR = 1.07)25. In the present study, the results suggested that AL did not impact long-term oncologic outcomes for locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer. Our previous study also confirmed by multivariate Cox regression analysis that AL was not an independent prognostic factor of OS and DFS23. Due to the limited number of AL cases in our study cohort, it remains further studies to clarify the exact infuence of AL on survival.

In our study, diversion ileostomy did not significantly decrease the occurrence of AL in patients with locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer. However, it was observed that the onset of AL was delayed by approximately one week postoperatively in patients who underwent diversion ileostomy, compared to those who did not. This delay may be attributed to the reduction of pressure on the anastomosis and decreased contamination of the anastomosis following diversion of intestinal contents. In addition, the recovery time following AL in patients with diversion ileostomy was approximately 11 days, which was significantly shorter than the 20 days observed in patients without diversion ileostomy. A subgroup analysis of patients with diversion ileostomy indicated that nearly all individuals who did not experience AL underwent ileostomy restoration at an average of 5.5 months following stoma diversion. In contrast, the proportion of patients who underwent ileostomy restoration was comparatively lower among those who developed AL, with the time interval to ileostomy restoration being extended by approximately two months relative to those who did not develop AL. Overall, 7 patients did not undergo ileostomy restoration. Notably, 2 patients in the AL group did not return for restoration surgery, likely due to age considerations, as these patients were over 80 years old. In the non-AL group, 4 patients did not undergo ileostomy restoration due to distant metastases, which resulted in death within one year post-surgery. Additionally, one elderly patient did not undergo ileostomy restoration. Among the study population, 1.5% (12/809) experienced grade C AL and required a secondary operation. Of these cases, 3 patients who initially underwent surgery with diversion ileostomy received laparoscopic flushing of the abdominal abscess and placement of a laparoscopic double trocar for continuous peritoneal drainage. In contrast, 9 patients who did not have diversion ileostomy at the primary operation underwent peritoneal flushing with the addition of a diverting stoma. This also resulted in a longer recovery time of approximately 1 month in patients with grade C AL without a diversion ileostomy, and 1 of these patients had a permanent stoma due to local recurrence. We suggested that temporary diversion ileostomy may have a positive impact on healing anastomoses in cases of AL. Wu et al. found that temporary diverting stoma significantly expedited leakage recovery by 4 days in patients with non-severe AL in rectal cancer, particularly among those who did not undergo neoadjuvant therapy26. Further investigation was conducted to determine which subset of patients could potentially benefit from a diverting ileostomy following AL. Asari et al. reported that surgical technique and experience were significant factors influencing AL, with experienced operators potentially benefiting patients by selecting a protective diverting stoma in high-risk cases27. The current research study made a significant and original finding that DAV (OR = 0.078, p = 0.002) emerged as the sole independent risk factor for potential-diversion-benefit in patients with AL. The study established a DAV threshold of 8.6 cm and emphasized the heightened risk of AL in male patients. As a result, the study recommended that male patients with a DAV ranging from 7 to 8.6 cm may benefit from undergoing a diversion ileostomy after AL occurs in instances of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer.

The present study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, inherent bias is present due to its retrospective design. Despite efforts to mitigate bias through the use of PSM, not all potential confounders were balanced, potentially introducing new selection biases. Secondly, in light of patients with confirmed diagnoses of colonoscopic pathology from external hospitals but lacking specific colonoscopy reports detailing the distance from the anal verge, our study opted to use MRI instead of colonoscopic measurements to ensure data consistency and minimize gaps. Thirdly, while follow-up was deemed satisfactory, long-term functional outcome analyses were hindered by missing data, primarily attributed to patients lost to follow-up or deceased.

Conclusion

In summary, within the limitations of this study, the results indicate that the utilization of diversion ileostomy as a preventative measure for AL in cases of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer is not universally endorsed due to potential complications such as small bowel obstruction and wound infection. Nevertheless, in the occurrence of AL, diversion ileostomy may prove advantageous for patient recuperation. Particularly, male patients with a DAV ranging from 7 to 8.6 cm may experience benefits from undergoing diversion ileostomy subsequent to AL in cases of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Platell, C., Barwood, N., Dorfmann, G. & Makin, G. The incidence of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 9(1), 71–79 (2007).

Abudeeb, H. et al. Defunctioning stoma- a prognosticator for leaks in low rectal restorative cancer resection: A retrospective analysis of stoma database. Ann. Med. Surg. 21, 114–117 (2017).

You, X. et al. [Application of protective appendicostomy after sphicter-preserving surgery for patients with low rectal carcinoma who are at high-risk of anastomotic leakage]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 18(6), 573–576 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Diverting stoma versus no diversion in laparoscopic low anterior resection: a single-center retrospective study in Japan. In Vivo 33(6), 2125–2131 (2019).

Lee, B. C. et al. Defunctioning protective stoma can reduce the rate of anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients. Ann. Coloproctol. (2020).

Mrak, K. et al. Diverting ileostomy versus no diversion after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Surgery. 159(4), 1129–1139 (2016).

Salamone, G. et al. Usefulness of ileostomy defunctioning stoma after anterior resection of rectum on prevention of anastomotic leakage a retrospective analysis. Ann. Ital. Chir. 87, 155–160 (2016).

Glynne-Jones, R. et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 28(suppl_4), iv22–iv40 (2017).

Cancer, K. S. G. R. Essential items for structured reporting of rectal Cancer MRI: 2016 consensus recommendation from the Korean Society of Abdominal Radiology. Korean J. Radiol. 18(1), 132–151 (2017).

Beets-Tan, R. G. H. et al. Correction to: magnetic resonance imaging for clinical management of rectal cancer: updated recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur. Radiol. 28(6), 2711 (2018).

Chang, J. S. et al. The magnetic resonance imaging-based approach for identification of high-risk patients with upper rectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 260(2), 293–298 (2014).

Allison, A. S. et al. The angiographic anatomy of the small arteries and their collaterals in colorectal resections: some insights into anastomotic perfusion. Ann. Surg. 251(6), 1092–1097 (2010).

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240(2), 205–213 (2004).

Salvadalena, G. D. The incidence of stoma and peristomal complications during the first 3 months after ostomy creation. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 40(4), 400–406 (2013).

Akesson, O., Syk, I., Lindmark, G. & Buchwald, P. Morbidity related to defunctioning loop ileostomy in low anterior resection. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 27(12), 1619–1623 (2012).

Verras, G. I. & Mulita, F. Butyrylcholinesterase levels correlate with surgical site infection risk and severity after colorectal surgery: a prospective single-center study. Front. Surg. 11, 1379410 (2024).

Kim, S. H., Park, I. J., Joh, Y. G. & Hahn, K. Y. Laparoscopic resection of rectal cancer: a comparison of surgical and oncologic outcomes between extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal disease locations. Dis. Colon Rectum 51(6), 844–851 (2008).

Park, J. S. et al. Multicenter analysis of risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic rectal cancer excision: the Korean laparoscopic colorectal surgery study group. Ann. Surg. 257(4), 665–671 (2013).

Iancu, C. et al. Host-related predictive factors for anastomotic leakage following large bowel resections for colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 17(3), 299–303 (2008).

Jestin, P., Pahlman, L. & Gunnarsson, U. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery: a case-control study. Colorectal Dis. 10(7), 715–721 (2008).

Makela, J. T., Kiviniemi, H. & Laitinen, S. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after left-sided colorectal resection with rectal anastomosis. Dis. Colon Rectum. 46(5), 653–660 (2003).

Rullier, E. et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 85(3), 355–358 (1998).

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Chen, J., Huang, S. & Huang, Y. Comparative analysis of preoperative chemoradiotherapy and upfront surgery in the treatment of upper-half rectal cancer: oncological benefits, surgical outcomes, and cost implications. Updates Surg. 76(3), 949–962 (2024).

Mirnezami, A. et al. Increased local recurrence and reduced survival from colorectal cancer following anastomotic leak: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 253(5), 890–899 (2011).

Lu, Z. R., Rajendran, N., Lynch, A. C., Heriot, A. G. & Warrier, S. K. Anastomotic leaks after restorative resections for rectal cancer compromise cancer outcomes and survival. Dis. Colon Rectum 59(3), 236–244 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Temporary diverting stoma improves recovery of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 15930 (2017).

Asari, S. A., Cho, M. S. & Kim, N. K. Safe anastomosis in laparoscopic and robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a narrative review and outcomes study from an expert tertiary center. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 41(2), 175–185 (2015).

Funding

This study was financially supported by Tai’an Science and Technology Development Plan Foundation of Shandong Province (No. 2022NS233).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yangyang Wang and Xiaojie Wang found the data curation and wrote the original draft. Heyuan Zhu and Shenghui Huang suggested the methodology and visualization. Ying Huang gave the supervision and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Huang, S. et al. Impact of diversion ileostomy on postoperative complications and recovery in the treatment of locally advanced upper-half rectal cancer. Sci Rep 14, 26812 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78409-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78409-z