Abstract

Adults with cancer may perceive cannabis as beneficial for managing their cancer-related symptoms, but the evidence supporting its medical use is varied and inconclusive. This study characterized associations of cannabis use with cancer-related symptom trajectories. Participants were adults undergoing cancer treatment at the Stephenson Cancer Center (SCC; n = 218) in Oklahoma; they were 71% female, 10% minoritized race, and 45% had stage III or IV cancer. Participants completed surveys at baseline and 2-, 4-, and 6-months post-baseline. Assessments queried about cannabis use behavior, physical and psychological distress via the Rotterdam Symptoms Checklist (RSCL), respiratory symptoms via the American Thoracic Society Questionnaire (ATSQ), and quality of life indices (physical and social functioning, pain interference, sleep quality, fatigue) via the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29). Cannabis use status was categorized based on self-reported past 30-day cannabis use at each assessment as non-use [no use at any assessment], occasional-use [use at 1–2 assessments], or consistent-use [use at 3–4 assessments]. Longitudinal hierarchical linear modeling evaluated associations of cannabis use status with average symptoms and symptom trajectories across all four assessments. One-third (33%) of participants reported past 30-day cannabis use at ≥ 1 assessment. Participants who reported cannabis use (occasional-use and consistent-use) had more severe symptoms overall across assessments. While most cancer symptom trajectories did not differ by cannabis use status, participants who reported consistent cannabis use uniquely showed worsening physical function over time. Cannabis use was associated with greater cancer-related symptom severity over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Legal medical cannabis has proliferated in the U.S. and has demonstrated some efficacy for the treatment of certain health conditions in select populations1,2. Approximately 20–30% of individuals undergoing cancer treatment have reported past 30-day cannabis use3,4,5,6,7. Adults with cancer have reported that cannabis can alleviate common cancer-related symptoms and treatment side effects, such as sleep problems, nausea, vomiting, and pain8. A study of patients receiving cancer treatment indicated that 29% of participants were interested in trying medical cannabis9. The findings of another study indicated that over 75% of patients with cancer wished to receive information about medical cannabis from their treatment team6.

There remains little clinical data to support either the antitumor effects of cannabis and cannabinoids10 or their ability to promote increased appetite and weight gain in cancer patients11. In their report on the health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded that “substantial evidence” supports the effectiveness of cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting12. However, evidence supporting the efficacy of cannabis for treating other physical and psychological symptoms related to cancer and cancer treatment has been limited and inconsistent.

Many individuals report using cannabis to treat their cancer and/or alleviate associated symptoms, and many individuals with cancer express interest and openness to use cannabis under the guidance of a healthcare professional5,6. However, given the dearth of research, physicians and patients still have questions about the clinical utility and effectiveness of cannabis for a range of medical symptoms and conditions13,14. Patients with cancer may use cannabis for symptom management, often without sufficient medical advice, relying on personal experimentation, anecdotal reports from friends or peers, and other non-medical sources for information, like cannabis industry marketing15,16. While health professionals generally express support for the use of medical cannabis in clinical settings, there is a notable disparity between self-reported knowledge and beliefs and practices regarding medical cannabis17,18,19. For example, in a nationally representative sample of oncologists, the majority reported lack of confidence in their ability to make clinical recommendations about medical cannabis use (70%), but 79.8% still engaged in conversations about it with their patients and 45.9% recommended its use within the past year18.

Given the increasing number of states that have legalized medical cannabis use in the U.S. and the widespread interest in its use among cancer patients, cancer care providers must be ready to engage in informed discussions with their patients regarding cannabis’ potential benefits and harms. This study evaluated the relationship between cannabis use among cancer patients and subjective quality of life indicators such as pain, physical and psychological distress, and physical and social functioning. Specifically, the objectives of the study were twofold: (1) to compare the sociodemographic characteristics of adults undergoing cancer treatment in a state with legal medical cannabis based on multiple measurements of past 30-day cannabis use behavior (i.e., non-use, occasional use, consistent use) over a 6-month period, and (2) to examine the associations between cannabis use status and both quality of life and cancer-related symptom severity and trajectories over time.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

Data collection occurred between June 2020 and June 2022 at the Stephenson Cancer Center (SCC) in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Participants were eligible if they were: ≥18 years of age, receiving cancer care at the SCC, able to read and complete study questionnaires, and able to access the internet to complete surveys. Enrolled participants completed a baseline survey that assessed cannabis use, quality of life, and cancer-related symptoms. Participants were asked to complete three additional bi-monthly surveys over six months to characterize changes over time. Participants were originally compensated with a $25 gift card per survey (n = 155). To boost recruitment, compensation was raised to a $50 gift card per survey (n = 115). For additional details about the parent study, please reference Azizoddin et al.8. The study was approved by the IRB of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (#11680) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics and health history

At baseline, participants provided information on their age, biological sex, race, ethnicity, education, income, employment status, health insurance status, cancer type, cancer stage, and cancer treatment. Time since cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment status (active vs. non-active [follow-up care]) were determined through retrospective chart review. For incomplete diagnosis dates (n = 15), we used the first day of the known month or year. Time since diagnosis was calculated as the number of months between the diagnosis date and baseline survey completion. Active treatment encompassed various modalities including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, drug therapy, and hormone therapy. Patients were classified as receiving active treatment if they underwent any of these interventions during their 6-month study participation period.

Cigarette smoking and other tobacco use

At baseline, participants were asked, “In the PAST YEAR, indicate how often did you use cigarettes?” (0 = Never; 1 = Have used, but not in the past year; 2 = Monthly or less; 3 = 2–4 times a month; 4 = 2–3 times a week; and 5 = 4 or more times a week). Responses were categorized into never (0), former (1), or current (2–5) smoking.

Cannabis use

At baseline and at each of the 2-month, 4-month, and 6-month assessments, participants were asked to report the frequency of their past 30-day cannabis use, ranging from 0 to 30 days. Participants’ cannabis use status was categorized at each assessment as non-use (0 days) or past 30-day cannabis use (≥ 1 day). To generate a single time-invariant variable that captured cannabis use across the entire study period, the number of assessments at which participants endorsed past 30-day cannabis use (ranging from 0 to 4 assessments) was summed. Participants’ cannabis use was then classified into three categories: non-use (0 assessments), occasional use (1–2 assessments), and consistent use (3–4 assessments). Participants who were missing two or more assessments were considered missing and excluded from analyses.

Participants who indicated cannabis use at any assessment were asked to report the number of days (0–30) in which they had used each of the following modes of administration: smoked, ate, vaped, dabbed, dissolved in the mouth, or applied to the skin; participants could endorse multiple modes. Participants were asked to report on their medical cannabis license (MCL) status at all time points: “Do you have a medical marijuana/cannabis card issued by the Oklahoma Medical Marijuana Authority or by the issuing authority of another state?” (yes/no).

Cannabis use disorder identification test–revised (CUDIT-R)

The CUDIT-R is an 8-item self-report assessment designed to evaluate problematic cannabis use with good reliability and validity20. Each item was scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, resulting in a total score range of 0–32. Scores ranging from 8 to 11 indicated hazardous cannabis use, and scores ≥ 12 suggested probable cannabis use disorder (CUD).

Quality of life and cancer-related symptoms

Physical and psychological cancer-related symptoms were assessed via the 28-item Rotterdam Symptoms Checklist-Modified (RSCL-M), which has good reliability and validity21,22. Activity level was assessed elsewhere and was omitted from the RSCL-M to reduce item redundancy and participant burden. The RSCL-M is comprised of physical and psychological distress subscales, which can be combined into a total score reflecting overall distress. Using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 4 = Very much), participants evaluated the extent to which each symptom was troublesome over the past week, with higher scores reflecting greater impairment.

The frequency of respiratory symptom severity (e.g., morning cough, wheezing, shortness of breath when walking; response options 1 = Never to 5 = Everyday) was measured via the 8-item American Thoracic Society Questionnaire (ATSQ)23. Scores ranged from 8 to 40, and higher scores indicated greater frequency/severity of respiratory symptoms.

The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29) assessed quality of life and has good reliability and validity21. The PROMIS-29 scales capture physical function, pain interference, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and social function (4 items each, 20 total items). Participants rated their symptom severity in the past seven days using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very good). Raw scores were summed and then transformed into a t-score (mean = 50; SD = 10)24. Higher scores on the physical and social function scales indicated better functioning, while higher scores on pain interference, sleep disturbance, and fatigue indicated worse functioning.

Analytic plan

Means and frequencies were calculated to describe participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, symptoms, and cannabis use behavior at baseline overall and by cannabis use status (non-use, occasional, consistent). Longitudinal hierarchical linear modeling was employed to examine symptom severity (RSCL Physical, RSCL Psychological Distress, RSCL Total, ATSQ, PROMIS Physical Function, PROMIS Pain Interference, PROMIS, Sleep Disturbance, PROMIS Fatigue, PROMIS Social Function; 9 models total) across the four assessment points as a function of cannabis use status, time (i.e., assessment time point; centered at midpoint), and interaction of time-by-cannabis use status (i.e., trajectory of symptom change by group). Potential covariates were considered based on anticipated differences between the cannabis use groups at baseline, including age, race, biological sex, cancer stage, time since diagnosis, and smoking status. Of these variables, those that were not significant in any model were removed, resulting in final covariates of sex and smoking status.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 270 enrolled participants, five were excluded from analyses due to missing baseline cannabis use status. Additional participants were excluded from analyses for missing all symptom assessments (n = 4) and missing cannabis use status at ≥ 3 assessments (n = 43). Participants in the final analytic sample (N = 218) were primarily female (71.1%, n = 155), White (90.4%, n = 197), with an average age of 57.51 (SD = 13.02) years. A minority of participants reported current smoking (12.8%, n = 28) or former smoking (14.2%, n = 31), and 22.5% (n = 49) of participants reported having a state-issued MCL (at or after baseline). The most commonly reported cancer types were breast cancer (19.7%; n = 43), gynecologic cancers, including ovarian (10.1%; n = 22), endometrial (5.5%; n = 12), uterine (4.1%; n = 9), and cervical (0.9%; n = 2), followed by colon/rectum (8.3%; n = 18), prostate (6.9%; n = 15), lung/bronchial (5.0%; n = 11), and other or unknown cancer types (n = 36, 16.5%). Of the 217 patients in our final analytic sample with available chart review data, the average time since diagnosis was 25.09 months (SD = 34.04) and 82.5% (n = 179) were receiving current cancer treatment.

Cannabis use

Approximately one-quarter of the sample reported past 30-day cannabis use at each of the baseline (25.2%, n = 55), 2-month (24.5%, n = 50), 4-month (27.1%, n = 54), and 6-month assessments (24.0%; n = 46). In total, 33.0% (n = 72) of participants reported past 30-day cannabis use in at least one of the four assessments, and 26.6% (n = 58) reported past 30-day cannabis use at more than one assessment. A total of 44.3% (n = 94) of participants reported an annual household income of less than $50k, with 63.6% (n = 28) of those with consistent cannabis use falling into this lower income category. Cancer stages were evenly distributed among the cannabis use groups, with approximately half of individuals in each group classified as Stage I/II and the other half as Stage III/IV. See Table 1 for participant characteristics overall and by cannabis use status. Among participants who reported cannabis use, the most frequently reported modes of cannabis use were eating, smoking, and vaping (Table 2). At baseline and 6-month follow-up, 18.8% (n = 12) and 7.7% (n = 4) of participants, respectively, who had engaged in cannabis use within the past 6 months demonstrated scores reflective of hazardous cannabis use, while 4.7% (n = 3) and 11.5% (n = 6) exhibited scores aligning with probable CUD. Of the 49 participants who endorsed past 6-month use at baseline and were initially identified as having non-problematic use (CUDIT < 8) at baseline, 6.1% (n = 3) progressed to Hazardous Use, and 2.0% (n = 1) to possible CUD after 6 months (see Supplementary Table 1).

Cancer-related symptoms at baseline

Generally, participants who used cannabis occasionally or consistently reported higher baseline symptom scores than participants who endorsed non-use. Participants who reported occasional cannabis use also had lower scores on the PROMIS physical and social function scales compared to those who reported non-use (see Table 3).

Cancer-related symptoms over time

Main effects

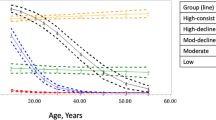

See Table 4 for model outcomes. Consistent cannabis use was associated with significantly more severe symptoms on all scales compared to those who did not use cannabis (i.e., lower scores on PROMIS physical and social scales and higher scores for the other scales; Fig. 1A–I). The main effect of occasional cannabis use was similar, except that ATSQ and PROMIS Sleep Disturbance symptoms did not differ significantly between those who reported occasional use and non-use (Fig. 1A–C, E,F, H,I). Females (vs. males) had significantly more severe symptoms on all scales except ATSQ, PROMIS Physical function (PF), and PROMIS Pain Interference (i.e., lower scores on PROMIS social function and higher scores for all other scales). Likewise, those who reported current smoking (vs. never smoking) had more severe symptoms on ATSQ, PROMIS Physical function, and PROMIS Pain Interference scales (i.e., lower scores on PROMIS physical scale, higher scores for the other scales).

Symptom trajectories over time for (A) RSCL physical, (B) RSCL psychological, (C) RSCL total, (D) ATSQ total, (E) PROMIS physical function, (F) PROMIS pain interference, (G) PROMIS sleep disturbance, (H) PROMIS fatigue, (I) PROMIS social function. Average differences in symptom trajectories were found for those with consistent use vs. those with non-use in all scales, and for those with occasional use vs. non-use in all scales but ATSQ Total and PROMIS SD. RSCL Rotterdam Symptom Checklist, ATSQ American Thoracic Society Questionnaire, PROMIS Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Interaction effects

There was a significant time-by-cannabis use status interaction effect on PROMIS PF, such that those who reported consistent use had a significantly negative trajectory (i.e., worsening of symptoms) compared to no significant change over time in the symptom in non-users. See Table 4; Fig. 1E.

Discussion

This study compared symptoms of adults undergoing cancer treatment by their cannabis use frequency over a six-month period. Approximately one-third (33.0%) of participants reported past 30-day use in at least one of the four assessments, and 26.6% reported past 30-day cannabis use at more than one assessment. Those who reported occasional or consistent cannabis use generally reported more severe symptoms (at baseline and, on average, over time) relative to individuals who reported that they did not use cannabis. No changes in symptom trajectories were observed by cannabis use status for nearly all outcomes, with the exception that participants who reported consistent cannabis use showed worsening physical function over time. In contrast, individuals who used cannabis occasionally or who did not use cannabis showed stable physical function over time.

Notably, this study explored cannabis use patterns among cancer patients residing in a state with permissive medical cannabis laws. Oklahoma legalized medical cannabis in 2018, with no specific qualifying conditions required for obtaining an MCL; only a recommendation from a qualified physician is needed. Since legalization, dispensaries have rapidly proliferated, expanding access to a wide variety of cannabis products25. Among all study participants, 22.5% possessed an MCL, and 77.3% of participants reporting consistent use had an MCL. This suggests an association between possessing a patient cannabis license and greater cannabis use, perhaps due to greater access to and motivation to use cannabis. Nevertheless, it is possible that those without an MCL may also use cannabis at higher rates but feel less inclined to disclose their use due to social desirability and fear of being stigmatized for illegal use.

The cannabis use characteristics of patients with cancer in this study mirror previous findings. The past 30-day cannabis use rates in this sample are consistent with those among patients with cancer in other studies3,4,5,6, which are higher than the past 30-day cannabis use rates reported in the general population of U.S. adults26. Additionally, the most popular modes of consumption among individuals reporting past 30-day cannabis use included combustible and edible use, which is consistent with other research among adults with cancer6. One national survey of cannabis use conducted in 2017 listed smoking, eating, and vaporizing as the most popular modes of consumption among US adults with medical conditions27. Unfortunately, the popularity of smoking cannabis in this population5,6 may contribute to more severe respiratory symptoms28. Given that the effects of cannabis may vary by route of administration (e.g., onset, desirable, and undesirable effects)29, providers should consider these variations when tailoring medical cannabis recommendations to the needs and preferences of their patients.

At baseline, just under a quarter of participants who were using cannabis met the criteria for hazardous cannabis use. At the six-month follow-up, only a small number of individuals had transitioned between different levels of problematic use, resulting in a smaller proportion of respondents endorsing scores consistent with hazardous cannabis use, but an increased proportion of participants meeting the criteria for possible CUD. Analysis of baseline and average symptoms demonstrate that compared to those who reported they did not use cannabis, those who reported consistent cannabis use had more severe symptoms when scores were aggregated across time on all symptom assessments. In comparison, those who reported occasional cannabis use had greater symptom severity on all symptom assessments other than the ATSQ and PROMIS Sleep Disturbance. Cross-sectional studies have similarly found that patients with more severe baseline symptoms are more likely to report using medical cannabis4,30 and other studies, including several RCTs, have shown small improvements in pain symptoms31,32 with a reduction in opioid and other analgesic use33 and small increases in physical functioning34 among people with cancer who use cannabis. This appears to deviate from our results, which reported worsening physical functioning over time among consistent users. These results suggest that individuals may use cannabis to manage more severe symptoms that they may experience during cancer treatment. However, other potential cause-and-effect dynamics should be considered. It is possible that cannabis use exacerbates cancer-related symptoms, leading to worse outcomes. Cannabis is known to have both psychoactive and physical effects, which may interfere with the body’s ability to manage cancer-related symptoms or negatively interact with cancer treatments. It is also possible that individuals with worsening symptoms seek relief through cannabis use, but that prolonged consumption unintentionally results in the worsening of some symptoms over time. Additionally, lifestyle factors like smoking or alcohol use, often associated with both symptom severity and cannabis use, could confound these relationships, obscuring the distinction between the direct effects of cannabis and other health behaviors.

There were several limitations worth noting. First, a causal relationship between cannabis use and cannabis-related symptom trajectories could not be determined in this study. Randomized controlled trials will be needed to rigorously evaluate the impact of cannabis use on cancer-related symptoms and physical functioning. Second, this study relied on self-report data, which may have resulted in underreporting of cannabis use. Evaluating cannabis use through the measurement of THC or THC metabolites in blood or urine would aid in a more accurate and objective assessment of use. However, studies have demonstrated that clinicians often underestimate the severity of patients’ symptoms and levels of functioning, particularly when symptoms are more severe35,36. This highlights the importance of incorporating patient self-reports into an understanding of patient’s quality of life.

Third, the study was limited by missing data, particularly regarding cannabis use status. Of the 261 participants, 16.5% (n = 43) were missing cannabis use data at one or more assessments. Fourth, the sample size was modest, and recruitment occurred at a single cancer center in Oklahoma, which may limit generalizability of the findings to other regions. Additionally, the legal status of cannabis in Oklahoma (medical use only) may also limit the applicability of the results to states with different cannabis regulations. It was also required that patients have access to internet to complete surveys. The study population primarily consisted of women (71%) and individuals who identified their race as White (90%), which may reflect uneven recruitment across cancer clinics with a predominance of certain cancer types specific to females (e.g., breast, ovarian, endometrial, uterine), the demographic composition of the state and the typical patient population seen at this cancer center. Lastly, we did not distinguish between medical and recreational cannabis use and modes of cannabis use in our analyses, nor did we collect survey data on cannabis dose. Reason for use (medical vs. recreational), modes of use, and dosing may separately and independently impact symptom management and cancer treatment outcomes and should be explored in future research.

Despite the noted limitations, the study has several strengths. The prospective longitudinal design allowed for repeated measurement of cannabis use and cancer-related symptoms over time, providing important insights into how symptom trajectories evolve in relation to cannabis use. Additionally, the use of hierarchical linear modeling to evaluate symptom trajectories enabled the inclusion of multiple time points and accounted for both within- and between-subject variability, allowing for more precise modeling of changes in symptoms over time. Furthermore, in the context of growing legalization and widespread use of medical cannabis among cancer patients, this study contributes valuable longitudinal data to a growing body of literature on the role of cannabis in symptom management for cancer patients.

Conclusion

Outcomes from this longitudinal observational study suggest that cancer-related symptoms were more severe over time among those who used cannabis (either consistently or intermittently) compared to those who did not. Symptom trajectories did not differ between the cannabis use groups over time, except for the physical functioning, which worsened over time among those who used cannabis consistently. These results do not directly support the medical benefits of cannabis use among patients with cancer. In contrast, findings suggest the possibility that cannabis use is appealing or has greater benefit among individuals with more severe symptoms or that cannabis use exacerbates cancer-related symptoms. Findings highlight the need for further research to characterize the directionality of the association between cannabis use and symptom severity in clinical and non-clinical populations.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Whiting, P. F. et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 313(24), 2456–2473 (2015).

Boehnke, K. F., Dean, O., Haffajee, R. L. & Hosanagar, A. US trends in registration for medical cannabis and reasons for use from 2016 to 2020: an observational study. Ann. Intern. Med. 175(7), 945–951 (2022).

Mousa, A., Petrovic, M. & Fleshner, N. E. Prevalence and predictors of cannabis use among men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 14(1), E20 (2020).

Donovan, K. A. et al. Cannabis use in young adult cancer patients. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 9(1), 30–35 (2020).

Hawley, P. & Gobbo, M. Cannabis use in cancer: a survey of the current state at BC cancer before recreational legalization in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 26(4), 425–432 (2019).

Pergam, S. A. et al. Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer 123(22), 4488–4497 (2017).

SAMHSA. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2002–2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29394/NSDUHDetailedTabs2019/NSDUHDetTabsSect7pe2019.htm

Azizoddin, D. R. et al. Cannabis use among adults undergoing cancer treatment. Cancer 1, 1 (2023).

Raghunathan, N. J. et al. In the weeds: a retrospective study of patient interest in and experience with cannabis at a cancer center. Support. Care Cancer 30(9), 7491–7497 (2022).

Abrams, D. I. & Guzman, M. Cannabis in cancer care. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 97(6), 575–586 (2015).

Strasser, F. et al. Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial from the Cannabis-In-Cachexia-Study-Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 24(21), 3394–3400 (2006).

National Academies of Sciences E & Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research (2017).

Adler, J. N. & Colbert, J. A. Medicinal use of marijuana—polling results. N. Engl. J. Med. 368(22), e30 (2013).

McLennan, A., Kerba, M., Subnis, U., Campbell, T. & Carlson, L. Health care provider preferences for, and barriers to, cannabis use in cancer care. Curr. Oncol. 27(2), 199–205 (2020).

Braun, I. M. et al. Cancer patients’ experiences with medicinal cannabis–related care. Cancer 127(1), 67–73 (2021).

Weiss, M. C. et al. A Coala-T‐cannabis survey study of breast cancer patients’ use of cannabis before, during, and after treatment. Cancer 128(1), 160–168 (2022).

Gardiner, K. M., Singleton, J. A., Sheridan, J., Kyle, G. J. & Nissen, L. M. Health professional beliefs, knowledge, and concerns surrounding medicinal cannabis—a systematic review. PLoS ONE 14(5), e0216556 (2019).

Braun, I. M. et al. Medical oncologists’ beliefs, practices, and knowledge regarding marijuana used therapeutically: a nationally representative survey study. J. Clin. Oncol. 36(19), 1957 (2018).

Zolotov, Y., Metri, S., Calabria, E. & Kogan, M. Medical cannabis education among healthcare trainees: a scoping review. Complement. Ther. Med. 58, 102675 (2021).

Adamson, S. J. et al. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: the cannabis use disorders identification test-revised (CUDIT-R). Drug Alcohol Depend. 110(1–2), 137–143 (2010).

De Haes, J., Van Knippenberg, F. & Neijt, J. Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients: structure and application of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist. Br. J. Cancer 62(6), 1034–1038 (1990).

Stein, K. D. et al. Validation of a modified Rotterdam Symptom Checklist for use with cancer patients in the United States. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 26(5), 975–989 (2003).

Comstock, G. W., Tockman, M. S., Helsing, K. J. & Hennesy, K. M. Standardized respiratory questionnaires comparison of the old with the new. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 119(1), 45–53 (1979).

Health Measures Northwestern University. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/calculate-scores (Accessed 19 December 2020).

Cohn, A. M. et al. Population and neighborhood correlates of cannabis dispensary locations in Oklahoma. Cannabis 6(1), 99 (2023).

SAMHSA. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt39441/NSDUHDetailedTabs2021/NSDUHDetailedTabs2021/NSDUHDetTabsSect1pe2021.htm#tab1.71a (2021).

Dai, H. & Richter, K. P. A national survey of marijuana use among US adults with medical conditions, 2016–2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2(9), e1911936 (2019).

Tashkin, D. P. & Roth, M. D. Pulmonary effects of inhaled cannabis smoke. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 45(6), 596–609 (2019).

MacCallum, C. A. & Russo, E. B. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 49, 12–19 (2018).

Macari, D. M., Gbadamosi, B., Jaiyesimi, I. & Gaikazian, S. Medical cannabis in cancer patients: a survey of a community hematology oncology population. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 43(9), 636–639 (2020).

Aviram, J. & Samuelly-Leichtag, G. Efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Phys. 20(6), E755 (2017).

Anderson, M. Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/06/13/mobile-technology-and-home-broadband-2019/ (Accessed 11 April 2020).

Zylla, D. M. et al. A randomized trial of medical cannabis in patients with stage IV cancers to assess feasibility, dose requirements, impact on pain and opioid use, safety, and overall patient satisfaction. Support. Care Cancer 29(12), 7471–7478 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic non-cancer and cancer related pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 374, 1 (2021).

Stephens, R., Hopwood, P., Girling, D. & Machin, D. Randomized trials with quality of life endpoints: are doctors’ ratings of patients’ physical symptoms interchangeable with patients’ self-ratings? Qual. Life Res. 6, 1 (1997).

Titzer, M., Fisch, M. & Kristellar, J. Clinician’s assessment of quality of life (QOL) in outpatients with advanced cancer: how accurate is our prediction? A Hoosier oncology study. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 20, 384 (2001).

Funding

This research was supported by Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (TSET) grant R22-03. Manuscript preparation was additionally supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [Grant Number 1K01MD015295-01A1] and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520 awarded to the Stephenson Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K., A.C., S.U., C.H., A.A., K.M., L.H., and L.Q. were responsible for conceptualization. L.B. (primary), M.C. (supervisor), and T.N. were responsible for formal analysis. D.K. was responsible for funding acquisition. T.N., L.B., A.C., and D.K. were responsible for methodology. T.N. and L.B. were responsible for visualization. T.N was responsible for writing the original draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Kendzor and Businelle are inventors of the Insight Mobile Health Platform (not used or evaluated in the current study) and receive royalties for the external use of the platform outside of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Kendzor is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Qnovia. Inc., which is a drug development company focused on inhaled therapies including prescription inhaled nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (no medications provided or evaluated in the current study). Kendzor previously received medication (varenicline) at no cost from Pfizer to support a now completed pilot study (no medications provided or evaluated in the current study). The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niznik, T., Boozary, L., Chen, M. et al. Symptom trajectories over time by cannabis use status among patients undergoing cancer treatment. Sci Rep 14, 28319 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78501-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78501-4