Abstract

This paper presents a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis and blade element momentum (BEM) analysis of horizontal small-scale wind turbines under various parameters. Random airfoils such as the NACA 0012, NACA 0018, NACA 4412, S1016, S1210, S1223, and SC20402 are chosen, and the glide ratio is analysed. A Reynolds number of 100,000 is considered because of the small wind turbine design. The foil with the highest glide ratio is selected. Various notations are used to represent the chord and the twist angle of the blade, and the blade with the best chord and twist angle is chosen. The lift, drag, and power coefficients and power curves are analysed via the BEM. The power curves are evaluated for different air densities, and a higher value of power is obtained. Finally, via CFD, the SST \(K-{\omega }\) model for turbulence is analysed for various angles of attack via Ansys Fluent for different air densities. The results are satisfactory compared with those of the CFD and BEM analyses. The Weibull distribution is analysed to understand the required frequencies for various wind speeds so that the installation of wind turbines can be made convenient in preferred areas with suitable wind properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most promising renewable energy sources currently being developed is wind energy. Until recently, building wind turbine blades using existing airfoil families, such as the well-known NACA series, has been common, but the need to advance wind turbine technologies has prompted the search for alternatives. A greater comprehension of the flow field may lead to design modifications that greatly enhance performance. There is much interest in determining aerodynamic properties via computational fluid dynamics because performing wind turbine experiments is expensive1. The aerodynamic performance of a wind turbine blade can be analysed via computational fluid dynamics. Horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs) and vertical-axis wind turbines (VAWTs) are the two main types of wind turbines. HAWTs are used commercially for large-scale power production because they are more effective than VAWTs2. The development of horizontal axis wind turbine (HAWT) technologies, which are clearly at the top of the market right now, is evidence that wind energy conversion has experienced substantial growth around the world3. In addition, novel alternative turbine technologies, particularly vertical-axis wind turbines (VAWTs) for building augmentation (roof installation) in urban environments, are being investigated, which demonstrates the interest of researchers in wind energy. Owing to their low tip speed ratios, insensitivity to the yaw angle, and ground positioning of their mechanical and electrically heavy sections, vertical-axis wind turbines are renowned for producing relatively little noise4. Wind tunnel testing is used in traditional research investigations for lower Reynolds numbers and lower angle of attack values56. The blade element moment is a reliable and easy way to investigate the lift, drag and momentum coefficients. Compared with real-time wind tunnel testing, it is a less expensive and efficient way to analyse data7. Vaz et al8. studied and created a mathematical model based on BEM theory for horizontal-axis wind turbine design and compared it to Glauert’s model. Miller et al9. reviewed numerical studies on wind energy, focusing on wind analysis and predictions, blade modelling and optimization, CFD, FEA (structural) and BEM for analysis and optimization. The prediction of turbine performance requires the prediction of blade aerodynamics. The two major methods for numerical aerodynamic prediction are (1) blade element momentum (BEM) theory and (2) CFD to solve the Navier-Stokes equations. Yong Zhuang and Guangming Yuan10studied the structural parameter changes in the blade tip, middle and root regions of a longer wind turbine blade with an NREL 5 MW wind turbine blade as an example by using the combined techniques of EulerBernoulli beam theory and Theodorsen nondirectional aerodynamic loads via FEM. Chi-Jeng Bai and Wei-Cheng Wang from the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics11, Taiwan, conducted a detailed review on the aerodynamics of HAWTs via BEM and CFD as a combined analysis along with an experimental approach. Dina Ahmed Hosni Salah et al12. performed a CFD analysis of a horizontal-axis dual rotor wind turbine of an S826 airfoil using k-shear stress transport turbulence models to solve for the 3D design and the turbulent, stable, and incompressible flow equations. The results are compared with the experimental data, and the effects on the efficiency of the wind energy are determined. A vertical-axis small-scale wind turbine with a rated power of 1 kW was investigated by Sukanta Roga et al13.. The research work was performed with an operational pitch angle control algorithm that allows the power to be below the rated value at wind speeds corresponding to high rated values. Shu et al14. presented a statistical analysis of the wind characteristics and wind energy potential at typical sites in Hong Kong via the Weibull distribution model, along with the variations in the mean wind speed and the Weibull parameters. Saleh et al15. studied different methods for estimating the Weibull distribution parameters for wind speed at the Zafarana wind farm, Suez Gulf, Egypt. Kang et al16. investigated the best method for estimating the Weibull parameters on Jeju Island, South Korea. Six methods for estimating the Weibull parameters were introduced, and their accuracy was evaluated via four accuracy tests for each parameter. Five-year wind data collected at nine Jeju sites with three different topographical conditions were analysed. Carrillo et al17. studied the Weibull distribution via wind speed data from weather stations in the city of Galicia, which is located in northwestern Spain. Pilar Díaz-Cuevas et al18. combined the use of geographical information systems and multicriteria decision methods for the southern part of Spain. Factors such as the wind speed and the wind power density for suitable and unsuitable geographical locations were discussed. Raquel Fernández-González et al19. performed a feasibility analysis of an average wind project in Galicia. The average wind speed and protected natural areas in Galicia for possible investments in Spain were discussed. Sukanta Roga et al20. used computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to analyse the energy performance of a vertical-axis wind turbine and a permanent magnet synchronous generator. To determine the maximal output power from the system, a power point tracking approach was used. The outputs, such as the voltage, current, power, rotor speed, power coefficient, electromagnetic torque and mechanical torque, were examined via the computational results. Sukanta Roga et al21. utilized Windographer software to analyse the wind energy potential at various locations in Nagpur city, India. The study involved the evaluation of monthly average wind speeds, wind power density, etc. A Weibull parameter study was conducted to evaluate the probability distribution function. These factors were considered together to establish each site’s classification. In this study, Weibull parameters were derived via four distinct methods to estimate the probability distribution function. The average wind power density and maximum capacity factor for the wind turbine were determined. Mekalathur B Haemanth Kumar22 conducted a wind energy potential assessment via Weibull parameter estimation in the Tirumala region in India. In this study, the Weibull parameters were used to analyse the wind data available at a particular location in the Tirumala region in India. An effort was made to study the wind potential in latitude and longitude regions (13°41′30.4″ N, 79°21′34.4″ E) via the Weibull parameters. For a total period of six years from January 2012 to December 2017, wind data were measured, and the following parameters were analysed: wind speed, wind direction, frequency distribution, mean wind speed, and parameters k and c of the Weibull distribution. A final comparison of wind farm locations in India was performed in this study. On the basis of this literature survey, in this study, a detailed step-by-step analysis of the blade design is conducted to obtain all the necessary parameters for the wind turbine, and CFD and BEM results are compared with experimental values to determine which method is better for performing the numerical analysis, ensuring that the parameters are considered for the Weibull analysis for the wind turbine installation. Hence, in this study, a detailed analysis is performed for a small-scale horizontal-axis wind turbine, starting with the foil selection, design analysis, and chord and twist analysis, and the power coefficient and power curves of the blade are determined in QBlade via BEM analysis. A blade with the required \(C_{p}\) value is considered, and the power curves are determined at different air densities of 0.882 and 1.776 in the BEM analysis. Similarly, CFD analysis is carried out for the required air densities. The lift-to-drag ratio (\({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\)) values obtained via the BEM and CFD analyses are compared, and the deviations are examined. The power curve is then evaluated for the required wind parameters, and the Weibull distribution is examined. This research provides insight into the aerodynamics of wind turbines by using both BEM and CFD analyses side-to-side to create better performing wind turbines. This Weibull analysis provides a clear path for identifying suitable locations for wind turbines for wind energy harvesting.

Governing equations

Theoretical analysis

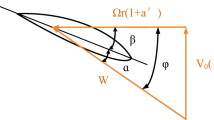

Chord and twist analyses play vital roles in the design of the wind turbine blade. Various authors have proposed different methods for calculating the chord and twist sections of a blade. In this work, four governing equations are considered, and a blade is designed.

Twist and chord length analysis model 1 suggested by Ingram23:

Twist and chord length analysis model 2 suggested by Jamieson24:

Twist and chord length analysis model 3 suggested by Hanson25:

where

Twist and chord length analysis model 4 suggested by Manwell et al.26:

Betz optimization27

The equations above are utilized for chord length and twist angle calculations, where B is the number of blades, \(C_{L}\) is the airfoil chord length, \({\lambda _r}\) is the local speed ratio, r is the radius of the inner blade and R is the radius of the outer blade. Via the above equations, the best values for designing a blade are determined, and a formula is established for analysing the blade design.

Next, the flow medium and the total energy equation, including viscous effects, are evaluated with the ideal gas law. The flow fluid is air under ideal gas conditions28. The governing equations for the simulation analysis can be written in the following form: For the turbulence model, the shear-stress transport SST k- \({\omega }\)is considered, with the dynamic viscosity of the power law equation of ideal gas air taken into account29.

Coefficient of dynamic viscosity:

where \(\mu\) is the viscosity kg/ms, T is the static temperature in K, \(\mu _{ref}\) is a reference value, and n is the number of moles of gas.

The actual power of the wind turbine is given by30. The power of the wind is determined via the equation below.

The power law

where \({C_{p}}\) is the power coefficient of the Betz limit of 0.593, \({\rho }\) is the density of the air, V is the velocity of the air and A is the cross-sectional area.

The lift coefficient \(C_{l}\), drag coefficient \(C_{d}\), lift force l and drag force dare evaluated in terms of motion31. To evaluate the airfoil and aerodynamic performance, \(C_{l}\), \(C_{d}\) and the glide ratio \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) are considered.

Lift coefficient:

Drag coefficient:

Lift force:

Drag force:

where “\(C_{l}\)” is the lift coefficient, which relates to the angle of attack (AOA) to the lift force; “\(C_{d}\)” is the drag coefficient, which relates the angle of attack (AOA) to the drag force; “v” is the velocity of air; “l” is the lift force; “d” is the drag force; “s” is the wing area.

Manwell et al26. explained that the Weibull distribution factor has two functional aspects, namely, the probability density function (PDF) and the cumulative distribution function, which are expressed as follows:

Probability density function

Cumulative distribution function

where V is the wind speed at m/s; K is the shape factor, which is dimensionless; and C is the scale factor in m/s. The Weibull distribution provides insight into the density and wind speed effects in various terrains and locations.

Boundary conditions

The shear-stress transport (SST) k- \({\omega }\)model was proposed by32,33 to effectively blend the robust and accurate formulation of the k- \({\omega }\) model in the near-wall region with the free-stream independence of the k- \({\epsilon }\) model in the far field. To achieve this, the k- \({\epsilon }\) model is converted into a k- \({\omega }\) formulation. The SST k- \({\omega }\) model is similar to the standard k- \({\omega }\) model but includes the following refinements: The standard k- \({\omega }\) model and the transformed \(k\) \(\epsilon\) model are both multiplied by a blending function, and the models are added together. The blending function is designed to equal one in the near-wall region, which activates the standard k- \({\omega }\) model, and zero away from the surface, which activates the transformed k- \({\epsilon }\) model. The SST model incorporates a damped cross-diffusion derivative term into the \({\omega }\) equation. The definition of the turbulent viscosity is modified to account for the transport of the turbulent shear stress. The modelling constants are different. These features make the SST k- \({\omega }\) model more accurate and reliable for a wider class of flows (e.g., adverse pressure gradient flows, airfoils, and trans-sonic shock waves) than the standard k- \({\omega }\) model. Other modifications include the addition of a cross-diffusion term in the \({\omega }\)equation and a blending function to ensure that the model equations behave appropriately in both the near-wall and far-field zones. Rao34 described the continuity, momentum and energy equations:

Continuity equation

Momentum equation

Energy equation

Transport equations for the standard k-\(\omega\) model

Transport equations for the standard k-\(\omega\) model

In these equations, \(G_k\) represents the generation of turbulence kinetic energy due to mean velocity gradients. \({G}_{\omega }\) represents the generation of \({\omega }\). \({{\Gamma }_k}\) and \({{\Gamma }_{\omega }}\) represent the effective diffusivities of k and \({\omega }\), respectively. \({Y_k}\) and \({Y_{\omega }}\) represent the dissipations of k and \({\omega }\) due to turbulence. \({S_k}\) and \({S_{\omega }}\) are user-defined source terms.

Solution procedure

Numerical models are generated via the QBlade and Ansys Workbench software packages. First, airfoil selection is performed. For this purpose, the QBlade software package is used to determine the lift-to-drag ratio \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) and interpret its values. In QBlade, further analysis is performed. For computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation, a 2D geometry is created in the Design modeller, and meshing is performed in the Ansys mesh section. The continuum simulations are based on the finite volume solution of the full two-dimensional NavierStokes equations for air under ideal gas conditions. The CFD simulations are performed by solving the NavierStokes equations. A grid-independent study is a critical process in which a mesh study must be performed before adopting suitable mesh settings for the remaining simulations. In this study, adaptive remeshing is performed on an airfoil with nodes and elements of three different sizes. Then, the required boundary condition is applied for the initialization, and the simulations are performed. After comparing the data, a Weibull distribution study is performed to identify locations that are suitable for installing wind turbines.

QBlade setup

In QBlade, all simulation objects and data are organized in a specific hierarchy to represent the fundamental components of a comprehensive wind turbine simulation encompassing aerodynamics, hydrodynamics and elasticity. The user defines aerodynamic parameters such as the Reynolds number and wind speed. QBlade then interpolates the values between sections. The global blade parameters include the number of blades. The distributed blade properties are categorized into basic and advanced aerodynamic blade properties. The basic blade properties consist of the following: Position [m] indicates the position of the section along the pitch axis of the blade, Chord [m] denotes the local chord length of the blade section, Twist [deg] represents the local twist of the blade section, and Foil refers to the airfoil object used for that section. QBlade helps construct wind turbine blades and analyse the power coefficient and power curves. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the set-by-step procedures used.

Foil selection

NACA foils such as NACA 0012, NACA 0018, NACA 4412, S1016, S1210, S1223 and SC20402 are randomly selected and analysed in terms of the glide ratio \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\)35. Haseeb Shah et al. demonstrated how to apply a direct method to design a small-scale wind turbine at a lower Reynolds number. The foil with the highest \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) values has the highest performance. The graph clearly shows that the NACA S1210 has the highest \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) value of 59.1 at an \(8.5^{\circ }\)angle of attack. There are only a few airfoils that operate under low Reynolds number conditions, which include S121036. The S1210 airfoil has been proven to perform better than symmetric or nonsymmetric NACA airfoils37. However, a 2D analysis of S1210 under low Reynolds number conditions was performed for a small turbine with a low Reynolds number and a high lift airfoil38.

Hence, NACA S1210 is taken into consideration for the analysis in this research. A graphical representation of the glide ratio obtained from the QBlade software package is shown in Figure 1.

The highest values of the glide ratio (\({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\)) obtained via QBlade analysis for all the analysed blades are presented in Table 1.

Design analysis

To construct the blade of the wind turbine, an initial 2D analysis is performed. Michael S. Selig and Bryan D. McGranaha39 studied the aerodynamic effects on small-scale wind turbines for different foils at a Reynolds number of 100,000. The 2D analysis is performed via the Q-Blade software package; hence, a Reynolds number of 100,000 is chosen. Once the blade is designed, a circular foil is created to fix the end of the blade.

Figure 2 shows the 2D representation of S1210 with a circular foil. After this, extrapolation of the lift and the drag coefficients of the foil is performed at a polar angle of 360 degrees.

The extrapolation is performed via the Montgomerie method. The extrapolated graphs are shown in Figure 3for both the lift coefficient and the drag coefficient at a polar angle of 360 degrees. A study was performed by40 in which the Montgomerie and Vieterna methods for extrapolation were compared, and both methods were in good agreement with each other; hence, the Montgomerie method is chosen in this study. The coefficients of the lift and drag graphs are obtained in QBlade for angles of attack ranging from -\(180^{\circ } +180^{\circ }\). During the work progress of the wind turbine blade, the foil operates under or above the initial expected range; hence, extrapolation is performed. At this time, the velocity and pressure distributions are analysed, which are explained in the comparison of the results in the computational analysis section.

Chord and twist design analysis

The chord and the twist are considered when constructing wind turbine blades. Ali Alkhabbaz et al41. described various theoretical methods for determining the linear chord length and twist angles, and finite element analysis and computational fluid dynamics investigations were conducted to examine the aerodynamic performance. The calculated twist and chord length values are shown in Figure 4.

Mehmet Numan Kaya et al42. studied forwards and backwards sweep blades for HAWTs with a blade span of 0.9 m and determined the aerodynamic effects via CFD. To obtain the optimum aerodynamic design of the blade, blade element momentum theory was applied11,26,43,44,45.

The calculated values are utilized in the QBlade software package by dividing the blade into 12 segments of 0.950 metres, and after optimization without any limit, the above designed blades are created. QBlade offers both manual and automated blade design options to streamline the process. It can automatically position the thread axis at the airfoil’s maximum thickness and optimize the blade shape for the best twist angle on the basis of a given tip speed ratio. The chord distribution can also be optimized according to Betz’s theories. Additionally, the blade design can be scaled to a different size via various scaling methods, including position scaling and twist and chord scaling. This provides a better power coefficient for the blade. Figure 5 shows a representation of blades with irregular shapes that were designed in QBlade. These blade shapes are quite different from those of standard blades; hence, Betz optimization is used. In this work, a blade with a length of 0.950 m is considered, and the chord and the twist of the blade are designed via the Betz method. The Betz optimization method is applied with a tip speed ratio of 7, and the angle of attack for the maximum \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) is taken into consideration and optimized, i.e., at 8.5 degrees, a maximum \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\)of 59.1 is obtained. The optimal tip speed ratio is 746. Thus, for high-performing wind turbines, a tip speed ratio of 7 should be considered47. A tip speed ratio (TSR) of 7 is often used for 3-blade wind turbines. The TSR is the ratio of the tangential speed of the tip of a wind turbine blade to the wind speed. It is an important factor in the design of wind turbines, as it directly affects the power generated. The chord and twist are obtained after the optimization of the blade via the Betz method. The distributions of the chord and twist angles from QBlade are presented in Figure 6.

The completely constructed blade is presented in Figure 7.

Power coefficient analysis

The generated blade is subjected to bending element analysis. Bending element analysis is performed to evaluate the power coefficient and the power produced by a small-scale wind turbine. Small-scale wind turbines are good power generators that are more compact and are installed in various places, from rural areas to developed cities, where large wind turbines are unable to be installed due to the requirement of vast land areas. Small wind turbines with power coefficient (\(C_p\)) values of 0.25 perform better than large wind turbines do48. The parameters considered are a wind speed of 1.55 m/s, an air density of \(1.176\,\hbox {kg/m}^{3}\), and a maximum number of iterations of 500. These values are obtained from the ideal gas and dynamic viscosity equations for air. Figure 8 shows a graphical representation of the \(C_p\) values obtained for all the above designed blades. Design 1 is the Ingram model, Design 2 is the Jamieson model, Design 3 is the Hanson model, Design 4 is the Manwell et al. model, and Design 5 is the Betz optimized model, whose corresponding \(C_p\) values are presented in Figure 8. The Betz optimized blade shows a superior value of the power coefficient \(C_p\), which is rated at 0.271 and is closer to the required \(C_p\) value. Hence, further analysis is carried out.

Power curve analysis

In general, small-scale wind turbines usually have rated powers of 0.2510 kW. In this research, rated powers from 0.25 kW to 10 kW are considered, and a better power range is identified from the graphs. This approach provides insight into how the rated power is generated, and the power curves are obtained via the pitch and stall methods. The values show that the rated power is optimized, and the values are compared to the stall conditions and the Betz limits of \(C_p=0.593\) and \(C_p=1\). This helps us understand the aerodynamic losses occurring in the designed blade and indicates that more efficient blades are needed.

Figure 9 shows that at a wind power of 10 kW, more maintenance is needed since the power curve does not stabilize at 10 kW. In the lower power curve regions, the power level stabilizes at very low wind speeds. For small wind turbines, for the power curve in the region from \({V_{rated}}\) to \({V_{cutoff}}\), the wind speed should be no less than 5 m/s50. For the power curve in the 5 kW region, the wind speed is higher than 5 m/s. For further analysis, the aerodynamic loss is studied with stall control and standard limits of the Betz function of \({C_{p}}=0.5\) and \({C_{p}}=1\). Figure 10 shows the detailed analysis.

The aerodynamic loss is the distance from the pitch control and stall control conjugate region to the \({C_{p}}=0.5\) curve. In Figure 10(a), the aerodynamic loss is greater in the 0.25 kW region, whereas in Figures 10(b) and 10(c), i.e., for 5 kW and 10 kW, the aerodynamic losses are much lower than those for 0.25 kW. For 10 kW, the stabilization is not optimal, and greater maintenance is needed to stabilize it; hence, 5 kW is the optimal blade power generation for this wind turbine analysis.

The influence of the air density is vital for understanding power generation; hence, the calculated power and the power curve from the QBlade are analysed. Two density parameter values of 0.882 and 1.176 are taken into consideration in the power law calculation. The graphs in Figure 11 clearly show that higher densities correspond to higher power efficiency; hence, the wind turbine should be installed in a region of higher air density. Such regions can be identified via Weibull distribution analysis.

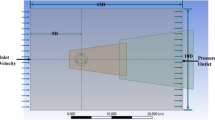

Design and mesh analysis for CFD

A 2D blade is designed in the Ansys designer by importing the blade coordinates from the air plotter in the same way as the data file was imported for the blade analysis. The design modeller is used to create the foil from the air plotter file and sketch the C-mesh domain. The fluid domain is created, and the boundary conditions, namely, the velocity inlet and the outlet conditions at the pressure outlet, are established.

A 2D design is created and subjected to meshing. Meshing is performed via the Ansys meshing tool. The mesh is created by bias conditioning, and a mesh convergence study is performed for three different types of meshes with varying numbers of nodes and elements. Meshing is performed with Y plus values of less than 1. A grid study is performed for the three meshes, and the convergence is examined. Table 2 shows the numbers of nodes and elements created for meshes A, B and C.

Table 3 shows the values of the drag coefficient \({C_{D}}\) and lift coefficient \({C_{L}}\) obtained from the different meshes for different angles of attack (AOA). The grid convergence data of the meshes for the physical parameters from the Ansys Fluent are shown in Figure 12, which presents the results of the mesh convergence analysis. The meshes A, B and C converge to one another for a better evaluation of the obtained values of the lift and drag coefficients. The results of the mesh convergence study are shown in Figure 12, including Mach number graphs and pressure coefficient graphs. All three meshes are in good correlation and converge to one another. Mesh B is selected to obtain better convergence results. Mesh B is used for further computations, and the results are obtained in Ansys Fluent software.

First, the structure of the mesh is described. After careful study, a final grid with 302000 elements and 303308 nodes is considered. The length of the domain is 15 m, and a c-shaped arc length of 7.5 m is taken into consideration for the 1 m length of the airfoil chord. The boundary layer mesh is clearly shown in Figure 13. Fig. 13 (a) shows the complete computational domain for mesh C. However, the mesh is highly dense at the airfoil region, front leading edge and back trailing edge. The normal spacing at the wall is stretched at a Y+ value of less than unity. The distance of the first grid node from the wall is 6.2793e-003 mm. To create a good quality mesh, factors such as orthogonal quality and skewness are taken into consideration. An average orthogonal quality of 0.97183 is obtained, which is great; usually, the best orthogonal quality is 0.951. An average skewness of approximately 8.8638e-002 is obtained, and the best quality range for the skewness factor is 00.25. The naming conditions are then determined, and a computational analysis is carried out.

Computational analysis

The computations are performed via Ansys Fluent 2021 version R2. The mesh is updated in the Fluent solver, and numerical solution is carried out using the standard K - \({\omega }\) shear stress transport (SST) to account for the turbulence effect.

Two air densities of 0.882 and 1.176 are taken into consideration, and the iterations are carried out at a low velocity of 1.55 m/s. The iterations are well run, and the report file data for the lift coefficient, drag coefficient, lift force and drag force values are determined for different angles of attack from \(-10^{\circ }\) to \(10^{\circ }\). This helps us to clearly understand the effects of deviation in the graph, in comparison with the BEM analysis. The boundary layer is clearly shown in Figure 14, which provides insight into the flow domain.

Figure 15 clearly shows the pressure distributions obtained via the QBlade and Fluent analyses with an angle of attack of -8 for both the BEM and CFD analyses. From the BEM analysis, the pressure distribution is represented by the red arrows, which indicate the greater influence of pressure on the foil, whereas the blue arrows indicate the lesser influence of pressure. At a negative angle of attack, the pressure distribution is observed in the lower region, and when the angle of attack reaches positive values, the pressure distribution is observed in the upper region of the NACA foil.

Figure 16 shows the velocity distributions of the 2D airfoils from the blade for both the BEM and CFD analyses at a positive angle of attack of 8. Both results show the distributions of the pressure and velocity. For the pressure distribution, -8 AOA is considered, and for the velocity distribution, +8 AOA is considered to determine the effects on the blade more clearly. A random AOA is chosen. Now, the values of the lift \(coefficient {C_{l}}\) and drag coefficient \({C_{d}}\) are obtained, and data are plotted.

The \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\)values are now compared with those of the BEM and CFD analyses. The experimental data are obtained from the prediction pole at RE=100,000 from the air plotter database50. The values are shown graphically in Figure 17. These findings indicate that all three sets of analytical data are relatively close to each other. The BEM values are more promising than those of the CFD analysis since the BEM analysis is less complex and much less time-consuming due to the fast iterations, whereas in the CFD analysis, the mesh convergence study and computations are quite complex and highly time-consuming. However, the accuracy is better than that of any other analysis. This makes the BEM analysis highly suitable for aerodynamic analysis of structured blades.

Figure 18 compares the results of the CFD analysis with different air densities, which are the same as those of the previous case. At a higher air density of 1.176, the lift coefficient value is higher, and will greater power is provided. This CFD analysis shows how the BEM analysis has a clear effect on the CFD data. CFD simulations are performed to demonstrate that high-density air corresponds to a relatively high glide ratio. The BEM and CFD analyses are performed for the 2D versions but not for the 3D versions because the 3D simulations in the CFD analysis would require more computational resources, and moreover, experiments are necessary to compare the results, which will be conducted in the future. This will help us compare the 3D blade obtained from QBlade, and the CFD simulations in Fluent will help us obtain a deeper understanding. Therefore, ensuring that the results obtained from the BEM analysis are clear and show the higher-density air regions will facilitate the installation of wind turbines. This provides insight into the Weibull distribution. The differences with the rotating blade will be identified and their significance will be investigated in future research since these issues are important.

Weibull distribution

Daniel Micallef and Gerard Van Bussel51 studied the Weibull probability distribution functions (PDFs) commonly used to characterize the wind speed magnitude frequency for different terrain types.

Table 4provides insight into the Weibull distribution and the K factors for different locations. Battisti et al52. explained that the statistical methods are usually adjusted by real density values of air at the installation location and that corrections are made due to changes in pressure or temperature. The maintenance or availability of the power grid is modified according to the performance of the system. The main disadvantage of this approach is that it is based on statistical models of wind measurements and the manufacturer’s P-V curve (i.e., generated power as a function of wind speed). These values are experimentally estimated in a wind tunnel with controlled parameters. Hence, in this study, to find the region with the highest air density, a small Weibull density distribution is used to clarify the distribution along with the wind speed.

The probability density function and cumulative distribution are studied for different k factors taken from the table and with wind speeds of 1.5 m/s, 3 m/s and 4.5 m/s, as presented in Figures 19 and 20. This shows that regions with higher air density in the Weibull distribution function should be taken into consideration, and wind turbines should be installed. This can result in highly efficient power generation from the wind turbines. The Weibull distribution provides a theoretical outline, but in practice, large amounts of data should be taken into consideration, such as data from wind stations or images from satellites for terrain location. Hence, the yearly energy generation of wind turbines can be calculated. Other factors, such as climatic conditions, which play vital roles, should also be considered.

The offshore and onshore energy produced can be evaluated via the Weibull distribution. The top five largest wind energy producers in the world are the USA, China, Germany, India and Spain. This approach aims to reach a relatively high energy yield from offshore wind turbines. The targets set to be achieved by 2030 are 90 MW for China; 30 MW for the USA, Germany and India; and 3 MW for Spain53.

A geographical representation is shown in Figure 21, which shows all five nations with the expected wind energy targets to be achieved by 2030. This will facilitate understanding of the most suitable geographical conditions of offshore regions on the basis of the Weibull k factor and aid in the identification of ideal locations for wind turbine installation. The energy produced from 2019 to 2021 is shown in Table 5.

Figure 22 shows geographical representations of two nations with widespread coastal areas. These areas can be explored with latitude and longitudinal values, which can help ensure the installation of onshore wind turbines and facilitate the achievement of the fixed targets for wind energy production by 2030.

Conclusions

In this research paper, a detailed study on the optimal design of a horizontal-axis wind turbine is presented. In addition, a 2D comparison of the BEM and CFD analyses is presented, along with a power analysis from the QBlade software package. In QBlade, a design can be constructed with less effort than via CAD, the blade can be exported to the CFD software, and aerodynamic analysis can be performed. The power curves clearly show that the aerodynamic effects of blades of small-scale wind turbines can be examined and that more efficient power systems can be generated. The SST k - \({\omega }\) turbulent flow model yields satisfactory results, and the lift coefficient (\({C_{l}}\)) and drag coefficient (\({C_{d}}\)) were analysed for the S1210 airfoil. The \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) values from the 2D BEM and CFD analyses are related, and a significant impact on the contours was observed in the CFD analysis. CFD analysis is time-consuming and requires higher computational costs to obtain better simulation results. However, 3D comparisons will be performed in future studies. The power curves from the blade analysis from QBlade provide sufficient values for understanding the effects of the wind speed on the designed wind turbine blade. The Weibull distribution shows how the impacts of the K and C factors vary from region to region and how potential universal areas with standard K and C values can be created with the designated regions. This will help us evaluate regions with higher pressure densities and cooler air regions in terms of climatic conditions. With the data obtained from this paper, further studies on the load evaluation of blades are needed to understand the use of finite element analysis and fluidstructure interactions. Turbine simulation, turbine wind speed generation and wave generation can be studied, along with the annual energy production (AEP) of the wind turbine. After this, 3D printing is suggested for evaluating real-time wind turbine blade production, and wind tunnel testing can be conducted for comparison. This will provide data on the yearly wind energy produced at the location, which can be compared with other Weibull distribution data from various literature sources. This Weibull distribution will give us a mean speed or a wind speed throughout the year, and a comparison of the data will guide the establishment of universal standards for the Weibull distribution. Hence, different locations from the two countries will be selected, and a geospatial analysis will be conducted to find an ideal location for wind turbine installation.

Data availability

All the data generated/analysed in the study are included in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BEM:

-

Blade Element Moment

- CFD:

-

Computational Fluid Dynamics

- HAWT:

-

Horizontal Axis Wind Turbine

- VAWT:

-

Vertical Axis Wind Turbine

- FEA:

-

Finite Element Analysis

- \({C_{l}}\)/\({C_{d}}\) :

-

Glide ratio / lift to drag ratio

- SST k \({\omega }\) :

-

Shear-stress transport K omega.

- \({C_{l}}\) :

-

Lift coefficient.

- \({C_{d}}\) :

-

Drag coefficient .

- \({F_{l}}\) :

-

Lift Force.

- \({F_{d}}\) :

-

Drag Force.

- AOA:

-

Angle Of Attack.

- \({\rho }\) :

-

Density of air

- v:

-

Velocity of Air

- B:

-

Number of blades

- \(C_{L}\) :

-

chord length

- \({\lambda _r}\) :

-

local speed ratio

- r:

-

Radius of the inner blade

- R:

-

Radius of the outer blade

- \({\phi }\) :

-

Relative wind speed angle

- \(\mu\) :

-

Viscosity

- T:

-

Static Temperature

- \(\mu _{ref}\) :

-

Reference value

- n:

-

Moles of the gas

- \({C_{p}}\) :

-

Power coefficient

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of air

- A:

-

Area of the cross section

- \({G_{k}}\) :

-

Turbulence kinetic energy

- \({G_{\omega }}\) :

-

Turbulence for \(\omega\)

- \({\gamma _{k}}\) :

-

Diffusivity of K

- \({\gamma _{\omega }}\) :

-

Diffusivity of \(\omega\)

- \({Y_{k}}\) :

-

Dissipation of K

- \({Y_{\omega }}\) :

-

Dissipation of \(\omega\)

- \({S_{k}}\) :

-

User-defined source of k

- \({S_{\omega }}\) :

-

User-defined source of \(\omega\)

- PDF:

-

Probability Density Function

- CDF:

-

Cumulative Distribution Function

- Kw:

-

Kilowatt

- AEP:

-

Annual energy production

- P:

-

Pressure

- MW:

-

Megawatt

References

David Infield. Chapter 15 - wind energy. In Trevor M. Letcher, editor, Future Energy (Second Edition), pages 313–333. Elsevier, Boston, second edition edition, 2014.

Noyes, Carlos, Qin, Chao & Loth, Eric. Pre-aligned downwind rotor for a 13.2 mw wind turbine. Renewable Energy 116, 749–754 (2018).

Didane, D. H. et al. An aerodynamic performance analysis of a perforated wind turbine blade. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 160(1), 012039 (2016).

Battisti, L., Brighenti, A., Benini, E. & Raciti Castelli, M. Analysis of different blade architectures on small vawt performance. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 753(6), 062009 (2016).

Laitone, E. V. Wind tunnel tests of wings at reynolds numbers below 70 000. Experiments in Fluids 23(5), 405–409 (1997).

Mueller, T. J., Pohlen, L. J., Conigliaro, P. E. & Jansen, B. J. The influence of free-stream disturbances on low reynolds number airfoil experiments. Experiments in Fluids 1(1), 3–14 (1983).

Hansen, M. O. L., Sørensen, J. N., Voutsinas, S., Sørensen, N. & Madsen, H. . Aa. . State of the art in wind turbine aerodynamics and aeroelasticity. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 42(4), 285–330 (2006).

Vaz, Jerson Rogério Pinheiro., Pinho, João Tavares. & Mesquita, André Luiz Amarante. An extension of bem method applied to horizontal-axis wind turbine design. Renewable Energy 36(6), 1734–1740 (2011).

Miller, Aaron, Chang, Byungik, Issa, Roy & Chen, Gerald. Review of computer-aided numerical simulation in wind energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 25, 122–134 (2013).

Zhuang, Yong & Yuan, Guangming. Study on coupled mode flutter parameters of large wind turbine blades. Scientific Reports 14(1), 12804 (2024).

Bai, Chi-Jeng. & Wang, Wei-Cheng. Review of computational and experimental approaches to analysis of aerodynamic performance in horizontal-axis wind turbines (hawts). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 63, 506–519 (2016).

Salah, Dina Ahmed Hosni., Nosier, Mahmoud Abed El-Rasheed. & Hamed, Ashraf Mostafa. Investigation of the performance of a horizontal-axis dual rotor wind turbine. Scientific Reports 14(1), 6208 (2024).

Sukanta Roga, Nikhil K. Wanmali, Vivek Kisku, Soumyabrata Das, and Subir Datta. Development of pitch angle control algorithm for pmsg based wind energy conversion system. In 2022 1st International Conference on Sustainable Technology for Power and Energy Systems (STPES), pages 1–5, 2022.

Shu, Z. R., Li, Q. S. & Chan, P. W. Statistical analysis of wind characteristics and wind energy potential in hong kong. Energy Conversion and Management 101, 644–657 (2015).

H. Saleh, A. Abou El-Azm Aly, and S. Abdel-Hady. Assessment of different methods used to estimate weibull distribution parameters for wind speed in zafarana wind farm, suez gulf, egypt. Energy, 44(1):710–719, 2012. Integration and Energy System Engineering, European Symposium on Computer-Aided Process Engineering 2011.

Dongbum Kang, Kyungnam Ko, and Jongchul Huh. Comparative study of different methods for estimating weibull parameters: A case study on jeju island, south korea. Energies, 11(2), 2018.

Carrillo, Camilo, Cidrás, José, Díaz-Dorado, Eloy & Obando-Montaño, Andrés Felipe. An approach to determine the weibull parameters for wind energy analysis: The case of galicia (spain). Energies 7(4), 2676–2700 (2014).

Díaz-Cuevas, Pilar, Biberacher, Markus, Domínguez-Bravo, Javier & Schardinger, Ingrid. Developing a wind energy potential map on a regional scale using gis and multi-criteria decision methods: the case of cadiz (south of spain). Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 20(6), 1167–1183 (2018).

Nataša Tandir Raquel Fernández-González, Félix Puime-Guillén and Francisco Rodríguez de Prado (2023) Sustainability, investment strategy, and governance: evaluation of wind energy sector in north-west spain. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(3):2183420

Roga, Sukanta, Kisku, Vivek & Datta, Subir. Performance of a vertical wind turbine with permanent magnet synchronous generator. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Energy 175(4), 205–215 (2022).

Roga, Sukanta, Dahiwale, Hiren, Bardhan, Shawli & Sinha, Sunanda. Wind energy potential assessment: a case study in central india. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Energy 177(3), 130–148 (2024).

Mekalathur B Hemanth Kumar, Saravanan Balasubramaniyan, Sanjeevikumar Padmanaban, and Jens Bo Holm-Nielsen. Wind energy potential assessment by weibull parameter estimation using multiverse optimization method: A case study of tirumala region in india. Energies, 12(11), 2019.

Grant L. Ingram. Wind turbine blade analysis using the blade element momentum method. 2011.

Peter Jamieson. Rotor Aerodynamic Design, chapter 2, pages 65–78. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 2018.

Hansen, Martin O. L. & Johansen, Jeppe. Tip studies using cfd and comparison with tip loss models. Wind Energy 7(4), 343–356 (2004).

Manwell, James F., McGowan, Jon G. & Rogers, Anthony L. Wind energy explained: theory, design and application (John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

Robert Gasch and Jochen Twele. Blade geometry according to Betz and Schmitz, pages 168–207. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012.

Orin Flanigan. Chapter 4 - gas laws. In Orin Flanigan, editor, Underground Gas Storage Facilities, pages 32–39. Gulf Professional Publishing, Houston, 1995.

Frank M White and Joseph Majdalani. Viscous fluid flow, volume 3. McGraw-Hill New York, 2006.

Philip Kosky, Robert Balmer, William Keat, and George Wise. Chapter 16 - green energy engineering. In Philip Kosky, Robert Balmer, William Keat, and George Wise, editors, Exploring Engineering (Third Edition), pages 339–356. Academic Press, Boston, third edition edition, 2013.

Snorri Gudmundsson. Chapter 8 - the anatomy of the airfoil. In Snorri Gudmundsson, editor, General Aviation Aircraft Design, pages 235–297. Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston, 2014.

Menter, F. R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA Journal 32(8), 1598–1605 (1994).

F. Menter. Zonal Two Equation k-w Turbulence Models For Aerodynamic Flows, chapter 1, page 21. AIAA, 1993.

Singiresu S. Rao. Chapter 17 - basic equations of fluid mechanics. In Singiresu S. Rao, editor, The Finite Element Method in Engineering (Sixth Edition), pages 589–610. Butterworth-Heinemann, sixth edition edition, 2018.

Haseeb Shah and Bhattarai. Low reynolds number airfoil for small horizontal axis wind turbine blades. page 8, 11 2012.

Michael Selig, J Guglielmo, A Broeren, and P Giguere. Summary of Low Speed Airfoil Data, Volume 1. 01 1996.

Giguère, Philippe & Selig, Michael S. Low reynolds number airfoils for small horizontal axis wind thrbines. Wind Engineering 21, 367–380 (1997).

Chougule, Prasad & Nielsen, Søren. R. K. Simulation of flow over double-element airfoil and wind tunnel test for use in vertical axis wind turbine. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 524(1), 012009 (2014).

Selig, Michael S. & McGranahan, Bryan D. Wind Tunnel Aerodynamic Tests of Six Airfoils for Use on Small Wind Turbines. Journal of Solar Energy Engineering 126(4), 986–1001 (2004).

Mahmuddin, Faisal, Klara, Syerly, Sitepu, Husni & Hariyanto, Surya. Airfoil lift and drag extrapolation with viterna and montgomerie methods. Energy Procedia 105, 811–816 (2017).

Alkhabbaz, Ali, Ho-Seong Yang, A. H., Weerakoon, Samitha & Lee, Young-Ho. A novel linearization approach of chord and twist angle distribution for 10 kw horizontal axis wind turbine. Renewable Energy 178, 1398–1420 (2021).

Kaya, Mehmet Numan, Kose, Faruk, Ingham, Derek, Ma, Lin & Pourkashanian, Mohamed. Aerodynamic performance of a horizontal axis wind turbine with forward and backward swept blades. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 176, 166–173 (2018).

David Wood. Blade Element Theory for Wind Turbines, pages 41–55. Springer London, London, 2011.

A. L. Rogers F. Manwell, J. G. McGowan. Aerodynamics of Wind Turbines, chapter 3, pages 91–155. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 2009.

Emmanuel Branlard. Blade Element Theory (BET), pages 143–149. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017.

Çetin, N. S., Yurdusev, M. A., Ata, R. & Özdamar, A. Assessment of optimum tip speed ratio of wind turbines. Mathematical and Computational Applications 10(1), 147–154 (2005).

Yurdusev, M. A., Ata, R. & Çetin, N. S. Assessment of optimum tip speed ratio in wind turbines using artificial neural networks. Energy 31(12), 2153–2161 (2006).

Andreas Gross and Hermann Fasel. Numerical Investigation of Different Wind Turbine Airfoils, chapter 1, page 15. AIAA, 2011.

Ravi Anant Kishore, Anthony Marin, and Shashank Priya. Efficient direct-drive small-scale low-speed wind turbine. Energy Harvesting and Systems, 1(1-2):27–43, 2014.

Airfoil tools. http://airfoiltools.com/airfoil/details?airfoil=s1210-il, 2024.

Micallef, Daniel & Van Bussel, Gerard. A review of urban wind energy research: aerodynamics and other challenges. Energies 11(9), 2204 (2018).

Battisti, L., Benini, E., Brighenti, A., Dell’Anna, S. & Raciti Castelli, M. Small wind turbine effectiveness in the urban environment. Renewable energy 129, 102–113 (2018).

Walter Musial, Paul Spitsen, Patrick Duffy, Philipp Beiter, Matt Shields, Daniel Mulas Hernando, Rob Hammond, Melinda Marquis, Jennifer King, and Sriharan Sathish. Offshore wind market report: 2023 edition. U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information, 1(2023), 8 2023.

Radosław Wolniak and Bożena Skotnicka-Zasadzień. Development of wind energy in eu countries as an alternative resource to fossil fuels in the years 2016–2022. Resources, 12(8), 2023.

Kumar, Abhishek, Pal, Divyanshi, Kar, Sanjay Kumar, Mishra, Saroj Kumar & Bansal, Rohit. An overview of wind energy development and policy initiatives in india. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 24(5), 1337–1358 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support provided by SGIker of UPV/EHU.

Funding

The authors appreciate the support to the CIEMAT through the research program “Energía eólica offshore para el ensayo y el desarrollo energético de energías renovables e hidrógeno verde”. Additionally, thanks to the Research Group IT1514-22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkateswaran, V.K., Fernandez-Gamiz, U., Portal-Porras, K. et al. Numerical study on aerodynamics of small scale horizontal axis wind turbine with Weibull analysis. Sci Rep 14, 26790 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78503-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78503-2

This article is cited by

-

Numerical analysis and optimization of airfoil modeling related to vertical axis wind turbine

Discover Mechanical Engineering (2025)