Abstract

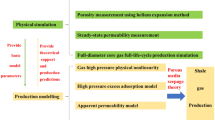

This paper first conducted a shale injection CO2 seepage experiment based on an improved single-vessel pressure pulse attenuation method. The experimental results reveal that the evolution pattern of shale permeability with respect to pore pressure can be divided into before and after phase change. The overall trend is that it first decreases and then increases, which is not a simple exponential form. The exponential fit of the permeability before and after the phase change alone is one-sided. A CO2 adsorption deformation test was subsequently conducted on shale under the same temperature and gas pressure conditions. The results revealed that with increasing CO2 pressure, the expansion and deformation of shale first increased but then decreased. The entire deformation process involves three deformation stages: a short compression stage, a slow expansion stage, and a stable deformation stage. The slip effect was corrected by combining adsorption expansion, effective stress, the real gas effect and the dynamic slip factor. The modified permeability model is more consistent with the relationship between permeability and pore pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing the proportion of unconventional natural gas represented by shale gas in primary energy consumption is crucial to achieving the dual-carbon goal1,2,3. China’s shale gas reserves below 3500 m account for more than 65% of total resources, and its recoverable volume ranks first in the world4,5,6,7. Owing to the low porosity and low permeability of reservoirs, shale gas production is very difficult8,9,10. The most common shale gas mining process is hydraulic fracturing. Allan Katende et al. studied the fracture proppant of hydraulic fracturing and explored the influence of fracture proppant on shale seepage characteristics considering multiple influencing parameters11,12,13. However, owing to the large regional environmental differences in the distribution of shale gas, not all shale gas reservoirs, such as some shale gas reservoirs in water-deficient areas, are suitable for hydraulic fracturing technology. Hydraulic fracturing has problems such as high water consumption and reservoir damage14,15. To solve the problems that occur when hydraulic fracturing is used to mine shale gas, efficient mining with supercritical CO2, which uses supercritical CO2to increase the permeability of shale reservoirs for shale gas production16,17, has been proposed. At present, CO2−enhanced shale gas extraction, the law of CO2 seepage and the evolution of shale permeability are not fully understood. For example, in the process of mining, the effective stress and slippage effect have competitive effects on the seepage of carbon dioxide in shale. Therefore, revealing the evolution of the permeability of shale considering the coupling of effective stress, the slippage effect and adsorption expansion is a key problem in engineering.

At present, the influence of effective stress on reservoir rock permeability has been widely verified18. Experimental results show that pore sensitivity is very important for the development of oil and gas resources and that microfractures in reservoirs are more sensitive to stress19. Zhou et al. reported that the effective stress is affected by the gas adsorption effect and subsequently affects the permeability of shale20. The natural microfracture permeability of shale reservoirs is more obviously affected by the effective stress, which can reach 80%21. Experiments have shown that the effective stress affects the permeability of shale by affecting its porosity22. When most researchers conduct effective stress analysis, they believe that under the same external stress conditions, the change in permeability with gas pressure is monotonic. However, owing to the special characteristics of CO2 in the pressure range with phase change, the change in permeability is not monotonic. It is necessary to further explore CO2 seepage in shale and the change in shale permeability during the phase change process.

Through microscopic experiments, Zhang et al. and others reported that adsorption expansion causes changes in the pores of coal samples and reduces permeability23. Many researchers have studied adsorption deformation in different gases, such as CO2, CH4, and N2. The results show that the adsorption expansion of shale has obvious anisotropy, which is closely related to the bedding of shale24,25,26,27,28. On the basis of adsorption experiments and adsorption deformation tests, scholars have introduced the adsorption effect into the permeability model to modify its effect on permeability29,30,31,32,33. Although many previous studies have been conducted on the influence of the adsorption effect on permeability, the combination of adsorption expansion and slippage effects needs to be further explored.

For CO2 storage projects, as the CO2 storage time increases, CO2 diffuses to the surroundings, the CO2pressure continues to decrease, the gas slippage effect cannot be ignored, and the permeability of low-permeability reservoir rocks rebounds34, which is related to the phase transition. The slip effect is a key factor in permeability changes. It is necessary to explore the slip effect under the influence of pore pressure coupled with a phase change pressure range to determine the CO2seepage law in shale. For the slip effect, the Klinkenberg equation is widely used in research. However, some experimental permeability results deviate from the results of the Klinkenberg linear Eqs35,36,37. For CO2 seepage in shale, it is necessary to further verify whether this equation is also applicable to the phase change process. The change in permeability during the phase change process needs further study.

Since the permeability of shale reservoirs is extremely low, for indoor permeability measurement experiments, the most commonly used steady-state method takes a long time, has low accuracy, and has stringent requirements for the measurement of the gas outlet, so the transient method is usually used to measure the permeability of extremely dense rock. Compared with the steady-state method, the transient method takes less time and has higher accuracy. Among the transient methods, the pulse attenuation method is the most commonly used38,39,40,41. The traditional pressure pulse attenuation method involves passing through two chambers upstream and downstream, and the pressure difference between the upstream and downstream chambers causes the upstream gas to automatically flow through the shale to the downstream chamber. This work uses an improved single-vessel pressure pulse attenuation method to conduct permeability measurement experiments. By reducing the number of chambers, the experimental error and experimental time are reduced40,41.

In summary, scholars have conducted many experimental studies on shale gas seepage under different working conditions, and further research is needed on the seepage characteristics of CO2 in shale. Most studies on CO2 percolation do not consider phase changes; most of them are separate studies before and after phase change, which limits the study of the pattern of change in permeability, and this cannot represent the entire process from low pressure to high pressure. This work uses an improved single-vessel pressure pulse attenuation method to measure the shale injection CO2 permeability experimentally and conduct CO2 deformation tests on shale adsorption under the same temperature and gas pressure conditions. By introducing adsorption expansion, effective stress, the real gas effect and the dynamic slip factor, the impact of multiple factors on the evolution of the permeability of CO2 injected into shale was explored.

Materials and experimental methods

Materials

The shale samples used in the experiments in this study were taken from an outcrop of tight shale in the Longmaxi Formation, Yanzi Village, Changning County, Yibin, Sichuan Province, China. The specific shale samples and sampling locations are shown in Fig. 1. Particle samples were cut from the same whole shale sample and crushed to less than 200 mesh (< 75 μm), and the crushed samples were thoroughly mixed to reduce inhomogeneity. The specific detailed parameters of the shale samples are shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Equipment, plan and steps for the seepage experiment

A diagram showing the device used in the seepage experiment is shown in Fig. 3. The purity of the gas used in the experiment is 99.99%. The maximum temperature that the water bath device can reach is 100 °C, and the accuracy is ± 0.01 °C. The upper limit of the pressure sensor is 100 MPa, the accuracy is ± 0.01 MPa, and the upper limit of the pressure that the core gripper can withstand is 60 MPa.

CO2 permeation experiment

CO2 permeation experiments in shale were carried out at a constant temperature (35 °C, 40 °C) and a gas pressure of 2.5 ~ 16 MPa. The specific scheme is shown in Table 4.

Figure 5(b) shows the specific experimental process. The pressure difference (DP) between Pci and Psi should be less than 10% of Psi42. After the initial point pressure is balanced, the pressure can be directly increased to the next test point. The subsequent pressure balance time can be shortened appropriately to reduce the experimental time and save experimental gas.

Equipment, plan and steps for the adsorption swelling experiment

A diagram of the device used in the adsorption swelling experiment is shown in Fig. 4. The upper limit of the pressure that the adsorption chamber and the reference chamber can withstand is 60 MPa. The data collection system includes a data collector and a static strain gauge (the accuracy of the strain measurement at 0 ~ 50 °C is 0.5% of the indicated value). The other devices are consistent with the seepage experimental device.

Adsorption swelling experiment

CO2 adsorption deformation experiments were carried out on shale at a constant temperature (35 °C, 40 °C) and a gas pressure of 2.5 ~ 16 MPa. The specific scheme is shown in Table 5.

Figure 5(c) shows the specific experimental process.

Permeability theory

Basic assumptions for the permeability calculations

To facilitate the calculation, the following appropriate assumption is made:

-

1)

After applying the pulse pressure, the physical properties of the gas before and after equilibrium remain unchanged.

-

2)

The porosity of the shale sample before and after equilibrium remains unchanged.

-

3)

Before and after equilibrium, the adsorption caused by the pressure difference is ignored.

-

4)

The laboratory temperature error was ignored, and the experimental temperature was held constant.

The phase diagram of CO2 is shown in Fig. 6(a). Owing to the particularity of CO2, the physical properties of CO2 differ under the experimental conditions of this study. Figure 6(b) shows the change curve of CO2density with gas pressure under constant temperature conditions. For Hypothesis 1, when the added pressure is less than 10% of the original pressure43,44, the physical properties of CO2 change little. In the real gas correction section of this article, the effects of temperature and pressure on the CO2 density, compressibility, compression factor, and dynamic viscosity are introduced. The results show that under the experimental conditions in this work, the change in CO2physical properties before and after equilibrium is less than 1%, so this assumption is acceptable. For Hypothesis 2, since the pressure difference before and after equilibrium is less than 0.5 MPa, the change in porosity caused is less than 1%45, so this part of the change can be ignored. Regarding Hypothesis 3, in the subsequent adsorption experiments, according to Fig. 21, the difference in adsorption capacity caused by the pressure difference before and after equilibrium is less than 0.85% on average; therefore, this part of the adsorption effect can be ignored. For Hypothesis 4, owing to the long experiment duration and the influence of the laboratory environment, the temperature difference in laboratory equipment caused by the temperature difference between the morning and evening is less than 1 °C and can be ignored.

Using the above assumption to make appropriate simplifications, the axial density distribution governing equation is38,44

The equilibrium equation for the gas amount is as follows:

The molar mass of the upstream chamber is nc = ρcVc/M where ρc is the chamber gas density (kg/m3) and Vc is the upstream chamber volume (volume correction is required, m3). M is the molecular weight of the gas (kg/mol). The CO2 concentration in the sample is c=ρ/M, and Eq. (2) can be rewritten as

where λ is the ratio of the volume of the upstream chamber to the pore volume of the shale and L is the length of the shale (m).

The boundary conditions are as follows:

The initial conditions are \(\rho_{c}\mid_{t=0}=\rho_{ci}\) and\(\rho\mid_{t=0}=\rho_{si}\) .

The internal gas density model of a shale core sample is obtained via the Laplace transform of the above equation45:

where ρ∞ is the CO2 density after the pressure is balanced. λ satisfies the equation \(\tan(a_n)=-\lambda a_n\) .

Substituting Eq. (8) into Eq. (7) yields

Substituting the above equation into\(\lambda L\frac{{d{\rho _c}}}{{dt}}= K \frac{\partial\rho}{\partial x}\mid_{x=0}\) yields:

In Eq. (10), when t = 0, the gas density in the upstream chamber can be expressed as

Substituting the equality relation \(\rho_\infty=\frac{\rho_{ci}V_c+\rho_{si}V_\phi}{V_{\phi}+V_c}=\frac{\rho_{ci} \lambda+\rho_{si}}{1+\lambda}\) into Equation (11) yields

The mass fraction can be calculated via the following equation:

The ratio of the remaining gas to the sample entering the shale core can be expressed as

FR can be expressed as

Then,

The density is expressed as pressure for convenience. On the basis of the first assumption, when a real gas is considered, it can still be replaced, which is more conducive to subsequent calculations.

To facilitate the calculation and processing of the experimental data, the expressions for the early solution and the later solution are given.

Early solution:

where\(\tau=\frac{Kt}{L^{2}}\) is dimensionless. Figure 7(a) shows the early solution and general solution at different volume ratios λ. When τ ≤ 0.15 , the previous solution is approximated to the general solution. With increasing λ, when τ ≥ 0.15, the early solution is the same as the general solution, which is most obvious at λ = 100.

Later solution:

When τ ≥ 0.15, Equation (16) converges rapidly; then, when n > 1, the value after the second term can be ignored, and the solution is approximately

where a1 is the first nonzero and nonextreme positive solution to \(\tan(a_n)=-\lambda a_n\). Figure 7(b) compares the later solution and the general solution at different volume ratios (λ); when λ tends to infinity, Eq. (18) can be approximated as, where, , and42\(ln(F_R)=f+mt\), where \(f=ln\left(\frac{2 \lambda(1+\lambda)}{1+\lambda+\lambda^{2}a^{2}_{1}} \right)\),\(m=\frac{a^{2}_{1}K}{L^{2}}\), and\(K=\frac{k}{\phi \mu c_g}\) .

The final permeability equation is as follows:

where k is the permeability, (m2); cg is the compression coefficient of CO2, 1/Pa; µ is the dynamic viscosity of CO2; and Φ is the porosity of the shale sample.

Owing to the compressibility of the pores, the initial porosity is not accurate, so the porosity needs to be corrected before the carbon dioxide seepage experiment. Through He seepage experiments in shale, according to the initial and final equilibrium pressures of the experimental system, the porosity can be calculated via Boyle’s law, and because the amount of helium adsorbed is very small, it can be ignored; thus, the porosity can be calculated via the following formula:

The compression factor of helium comes from NIST. Owing to the strong adsorption of CO2, the porosity change caused by adsorption cannot be ignored. For carbon dioxide, the improved SRD model is more suitable; with the SRD adsorption model, the porosity caused by adsorption can be expressed as follows:

where D, nmax, and \(\frac{d\rho_a}{dp}\) can be obtained via adsorption experiments and real gas effects, as explained in the following chapters.

The apparent porosity of shale can be expressed as

Adsorption calculation

The initial and final pressure values of each equilibrium point reference chamber and adsorption chamber were recorded under isothermal conditions. The schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 8, and the cumulative adsorption amount can be obtained via Eq. (23).

The adsorption capacity can be expressed as

The cumulative adsorption amount\(N_{exp}^{i}=\sum_{i=1}^{n} \Delta N_{exp}^{i}\) . The total adsorption capacity is converted into the adsorption capacity of shale samples per unit mass, the gas volume under standard conditions (STP) is taken as the unit, and the adsorption capacity is\(n_{exp}=\frac{22400N_{exp}}{m}\) .

Because the volume of the adsorption chamber and the reference room is much larger than the volume of the pipeline and the valve, this part of the volume can be ignored.

Results and discussion

Permeability results

Volume correction

The relationship between α and λ is shown in Fig. 9. Since the volume of the upstream chamber is very small, the volume of the pipeline and valve connected to it cannot be ignored, and the actual volume needs to be corrected, as shown in Fig. 10. The correction equation is as follows:

The correction process is shown in Fig. 5 (a).

Real gas effects

Owing to the special nature of CO2, the physical properties of supercritical CO2 are very different from those of gaseous CO2. Therefore, the difference in the physical properties of CO2 at each measuring point (interval of 1.5 MPa) during the experiment in this paper cannot be ignored. Figure 11 (a) shows the compression factor of CO2. Under the experimental temperature conditions in this work, the compression factor first decreases but then increases with increasing pressure. Figure 11 (b) shows the dynamic viscosity of CO2. Unlike the compression factor, the dynamic viscosity gradually increases with increasing pressure. Figure 11 (c) is the compression coefficient of CO2, which decreases first and then increases with increasing pressure. Figure 11 (d) shows the density of CO2, and its change trend is consistent with that of the dynamic viscosity of CO2. The physical properties of CO2 change abruptly when it approaches the critical condition. To facilitate the calculation, the compression factor, compression coefficient and dynamic viscosity need to be determined. The equation for the compression factor Z is shown in Table 6.

Figure 12 (a) compares the compression factor Z fitting results and the Z (NIST) results of the three models. A comparison of the results of the three fitting equations reveals that the H−S−M method has the best fitting effect. Figure 12 (b) compares the H−S−M fitting results and the Z (NIST) data. The fitting error is shown in Fig. 14 (a). The overall error of the H−S−M method is less than 10%.

The dynamic viscosity of gas can be expressed as49

where ρ = MP/ZRT , ρ is the gas density considering the real gas effect, kg/m3; M is the molar mass of the gas, kg/mol; and R is the general gas constant J/(mol·K).

The compression coefficient of gas can be expressed by Eq. (27)40. The specific results are shown in Fig. 10 (c).

Figure 13 (a) shows the L101 and L102 fitting results compared with µ (NIST). Figure 13 (b) shows that the relationship between the fitting results of L101 and L102 and the µ (NIST) data can be fit with the standard linear function under the experimental conditions. Figure 14 (b) shows that the overall average error is less than 15%, which is acceptable.

Data processing

Since the pressure‒time curves of the upstream chamber under different pressures are similar, we discuss the results for sample L101 at a pressure of 2.5 MPa. Figure 15 shows the pressure decay curve with time and the FR−time curve under L101 2.5 MPa. Figure 15(b) shows that after the early decline, the later solution for the later time corresponds well with the experimental value. Through the slope of the later solution, the permeability of the core can be calculated. Figure 16 shows the curve of the m values of the two shale cores as a function of pressure. The figure shows that the change in slope can be divided into two stages: the gas phase before the phase change and the supercritical phase after the phase change. The absolute value of the slope in the supercritical phase increases with increasing pressure and tends to be linear. This situation may be due to the special physical properties of CO2, as shown in Fig. 11. When the pressure is close to the critical pressure, the physical properties change suddenly.

Figure 17 shows the permeability curves of two shale core samples with increasing CO2 pressure. The permeability clearly has an extreme value when the CO2pressure is close to the critical pressure, and the curves of the shale permeability and pore pressure are approximately ‘v’ shaped. The overall permeability change can be divided into two stages. 1: In the gas phase, when the pore pressure is low, the permeability decreases gradually. Ranathunga et al. suggested that the decrease in permeability was the result of matrix expansion. In the present work, we infer that the reduction is the common result of the Klinkenberg effect, expansion and effective stress50. As the pore pressure continues to increase, the permeability decreases. 2: In the supercritical state, the permeability of shale corresponds to the physical properties of CO2 (Fig. 11). There is a minimum inflection point near the critical pressure, and the permeability increases with increasing pressure. If the real properties of gas are ignored, the results will be greatly affected.

Mechanism of stress and adsorption strain in shale

Adsorption capacity and adsorption strain

Figure 18 shows the absolute adsorption capacity of CO2 in shale and the gas pressure curve. The diagram reveals that the amount of CO2 adsorbed in shale first increases and then decreases with increasing CO2 pressure, and the maximum value occurs near the critical pressure. A comparison of the adsorption capacity of the two shales revealed that under the same gas pressure conditions, the adsorption capacity in the early stage at 35 °C was greater than that at 40 °C. After exceeding the critical pressure, the adsorption amounts at the two temperatures tend to be equal.

At present, the adsorption models of coal and shale are mostly assumed to satisfy the Langmuir model. However, owing to the particularity of CO2, the Langmuir model cannot describe the adsorption of CO2 above 6 MPa. This is because the Langmuir model cannot describe the phase transition of CO2, whereas the supercritical DR model (SDR)[[51,52]] can describe the supercritical adsorption of CO2 by introducing density. The supercritical DR model is established with the conventional DR model. The conventional DR model is shown in Eq. (28).

where n is the excess adsorption capacity of the sample; nmax is the maximum adsorption capacity; p0 is the saturated vapour pressure of CO2; p is the adsorption pressure; and D is the characteristic coefficient of CO2 adsorption on the sample. Since the adsorption temperature exceeds the critical temperature of CO2, CO2 does not liquefy, and there is no saturated vapour pressure p0; thus, the conventional DR model cannot describe the adsorption conditions in the supercritical state. Replacing the pressure with density and introducing the density of the adsorbed phase yields Eq. 29.

where ρa is the density of CO2 and ρg is the density of the adsorbed phase.

The results of Reference52 show that the adsorption amount is linearly related to the deformation amount, and the correlation factor Q is introduced. Therefore, the model of adsorption deformation is as follows.

Let, \(\epsilon_{max}=n_{max}Q\) and K=K1Q ; then, it can be rewritten in the form of the SDR model.

As shown in Fig. 19, the axial (vertical bedding direction) strain and radial (parallel bedding direction) strain of the shale samples are consistent in terms of the overall change trend but exhibit significant directionality in deformation. The strain of vertical bedding is greater than that of parallel bedding, which shows that the adsorption deformation of shale is anisotropic. The pores and fractures in shale mainly develop along the bedding, and the adsorption expansion of shale mainly involves changes in the width of fractures and pores; thus, expansion deformation occurs mainly in the vertical direction of pores and fractures. The adsorption strain of shale can be calculated from the axial strain and radial strain.\(\epsilon=\epsilon_1=2\epsilon_2\) , where ε is the adsorption strain, ε1 is the axial strain, and ε2 is the radial strain.

As shown in Fig. 20, (a) shows a curve of the change in the adsorption strain with pressure, and (b) can be obtained by substituting the experimental data into Eq. (28). (b) shows that the SDR model can describe the expansion deformation of shale that adsorbs CO2.

The variation in the adsorption strain is \(\Delta\epsilon=\epsilon-\epsilon_0\) :

The volumetric strain and fracture strain caused by adsorption deformation can be expressed as.

Volumetric strain:

Fracture strain:

where f is the internal expansion coefficient, which is used to measure the influence of shale adsorption deformation on the change in pore and fracture width, and its fluctuation range is usually 0−1. A schematic diagram of shale adsorption deformation is shown in Fig. 21. Vm is the matrix volume, Vf is the pore fracture volume, and the shale volume is Vb.

Stress sensitivity

With the continuous change in pore pressure, stress directly affects the closure and opening of pores and fractures in shale reservoirs, which is very important for the permeability evolution of reservoirs. The volumetric strain and fracture strain caused by effective stress can be expressed as54,55

where Kb is the bulk modulus of shale, MPa; \(K_b=\frac{E}{[3(1-2\nu)]}\) ; E is the elastic modulus, MPa; v is Poisson’s ratio, dimensionless, \(\alpha=\frac{1-K_b}{K_m}\) ; and \(\beta=\frac{1-K_f}{K_m}\) . The total volumetric strain and rupture strain are as follows:

Some scholars believe that the relationships among the porosity, volumetric strain and fracture strain can be expressed via Eq. (39)3,43.

Generally, the bulk modulus of shale itself is much greater than that of shale pores. The bulk modulus of fractures is much lower than that of the shale matrix: Kb > > Kf, and Kb < < Km. When the rock porosity is far less than 1 and φ < < 1, the above equation can be integrated into

where\(C_f=\frac{1}{K_f}\).

Since Kb < < Km, α is almost equal to 1. According to the Betty‒Maxwell reciprocity law, \(K_f=\frac{\phi K_b}{\alpha}\) , and \(K_f {\approx \phi K_b}\) .

Combined with the above equations, we can obtain

The following relation is stipulated:

Slippage effects

Compared with conventional reservoirs, shale reservoirs have smaller pores and microcracks. Under low pore pressure, the gas flow rate at the edge of the wall is not 0, which makes the gas improve the flow capacity during the seepage process, thereby increasing the permeability. The yellow part in Fig. 22 is the ideal flow state, and the flow velocity in the pore is evenly distributed at a distance from the wall surface. Obviously, this flow velocity distribution is not correct, and the green part is a linear distribution. Owing to the intermolecular force, the probability of the molecules colliding and the friction between the fluid and the wall surface, the flow velocity is not linear in the distribution of the distance from the wall surface, which needs further discussion. Therefore, the permeability of this part needs to be corrected.

In an experiment, Klinkenberg reported an obvious inverse linear relationship between the permeability and pore pressure and presented an empirical first-order permeability correction equation such as Eq. (44). However, with increasing Knudsen number (Kn > 0.001), the gas flow in shale does not fully follow the Klinkenberg correction equation. On the basis of the Klinkenberg correction equation, Moghadam and Chalaturnyk proposed a higher-order equation to describe the slip effect56. The second-order permeability correction equation after correction is shown in Eq. (45).

where\(b=\frac{4m}{r_{pore}}\) ,\(a=\frac{4m^{2}}{r^{2}_{pore}}\),\(m=c\mu_g \sqrt{\frac{\pi RTZ}{2M}}\)57, and c is a dimensionless parameter.

Then, a and b can be expressed as

According to Reference58, we can obtain \(\phi=\frac{6r}{d}\) and, \(k=\frac{8r^{6}}{12d}\) .

Then, \(r=3\left(\frac{k}{\phi}\right)^{0.5}\) can be obtained according to the following relationship: \(\frac{k}{k_0}=\left(\frac{\phi}{\phi_0}\right)^{3}\) . Combined with Eq. (42), the following equation can be obtained:

Substituting Eq. (47) into Eq. (46) yields

The apparent permeability of shale modified by dynamic second-order slip can be obtained by substituting Eq. (48) into Eq. (45):

Liu et al36. and Heller et al59. reported that the change in effective stress has a greater effect on permeability than slippage has on permeability. Therefore, we believe that the effective stress plays a dominant role in the evolution of permeability in environments with increasing pore pressure. The traditional exponential form is not suitable for global fitting. We use the following equation to construct the permeability fitting function36,60,61.

Figure 23 compares the experimental data and the results of the three different fitting equations. Because the traditional exponential form cannot fit a nonmonotonic dataset with extreme values, the data before and after the extreme values are fitted piecewise. The construction function fits the global data well, and the fitting effect is good, which reflects the inflection point of the experiment well. However, for these two fitting methods, although the exponential form can reflect the monotonicity and trend of the data well, it cannot be defined globally when the pressures cross (covering low pressure, high pressure and the phase transition). Although the constructor can fit the global data well, its highest phase cannot be determined. Moreover, it cannot explain the problem, and the upper and lower limits of the order of magnitude of the fitting parameter are high. Figures 24 and 25 show the errors of the three fitting models. The numerical values indicate that the fitting degree of the three fitting models exceeds 95%, and the relationship between the fitting value and the experimental value is close to a linear function.

Conclusion

In this study, we explored the seepage law of CO2 in shale via an improved single-container pulse permeability measurement method and carried out shale adsorption CO2 expansion tests under the same temperature and gas pressure conditions. Combined with the real gas effect, adsorption strain and the slippage effect, the permeability was corrected, and the results of three fitting equations were compared. The specific conclusions are as follows.

-

1.

The evolution of permeability with respect to pore pressure after CO2 injection into shale can be divided into two stages: before and after phase change. In the gaseous CO2 stage, when the pore pressure is low, the permeability decreases gradually under the combined action of the slippage effect, adsorption expansion and effective stress. With the gradual increase in pore pressure, CO2 nears the phase transition, the slippage effect is weakened, the effective stress effect gradually increases, the permeability change gradually decreases, and the minimum value is reached. During the supercritical CO2 stage, the physical properties of CO2 change abruptly, and the trend of the change in permeability with increasing pore pressure changes from a decrease in the gas phase to an increase. In the early stage of the supercritical state, the increasing trend is small. With increasing pore pressure, the permeability clearly tends to increase, and the overall trend tends to decrease first and then increase.

-

2.

The expansion deformation of shale under CO2 pressure can be described in the form of a supercritical DR (SDR) model with CO2 density. The adsorption deformation of shale shows significant directionality. The strain of vertical bedding is greater than that of parallel bedding; that is, the adsorption deformation of shale is anisotropic. The trend of expansion deformation is similar to that of the adsorption capacity. Under the action of CO2 pressure, the deformation of shale undergoes three deformation stages: the transient compression stage, the slow expansion stage, and the stable deformation stage.

-

3.

In this work, the permeability model is corrected by considering the combined effects of adsorption expansion, effective stress and the slippage effect. Comparing two common fitting methods with the model in this paper shows that the model in this paper can not only better explain the evolution law of permeability after injection of CO2 in shale but also correspond to the physical changes in CO2, which can better explain the trend of the change in permeability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xinyuan Gao, S. et al. Effects of CO2 variable thermophysical properties and phase behavior on CO2 geological storage: a numerical case study. J. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 221, 125073 (2024).

Jun, W. A. N. G. et al. Effect of effective stress and slippage on deep shale gas seepage. J. J. CHINA COAL Soc. 48 (12), 4461–4472 (2023). (in Chinese).

Zeng, X. et al. New Model for Gas Transport in microfractures in Shale reservoirs: integration of effective stress, gas adsorption, and second-order slippage. J. Energy Fuels. 37, 13880–13897 (2024).

Yulong, Z. H. A. O. et al. Research progress on supercritical CO2 fracturing, enhanced gas recovery and storage in shale gas reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Ind. 43 (11), 109–119 (2023). (in Chinese).

Di Wu, W. et al. The permeability of shale exposed to supercritical CO2. J. Sci. Rep. 13, 6734 (2023).

Hongyan, W. A. N. G. et al. Enrichment characteristics, exploration and exploitation progress, and prospects of deep shale gas in the southern Sichuan Basin, China. J. OIL & GAS GEOLOGY. 06-1430-12. (in Chinese) (2023).

De Silva, P. N. K., Ranjith, P. G. & Choi, S. K. A study of methodologies for CO2 storage capacity estimation of coal. Fuel. 91 (1), 1–15 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Multiscale characterization of the Caney Shale - An Emerging Play in Oklahoma. J. Midcontinent Geoscience. 2, 33–53 (2021).

Fathi, E. & Akkutlu, I. Y. Multi-component gas transport and adsorption efects during CO2 injection and enhanced shale gas recovery. Int. J. Coal Geol. 123, 52–61 (2014).

Ghanizadeh, A. et al. Experimental study of fuid transport processes in the matrix system of the European organic-rich shales: I. Scandinavian Alum Shale. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 51, 79–99 (2014).

Allan Katende, J. et al. Convergence of micro-geochemistry and micro-geomechanics towards understanding proppant shale rock interaction: a Caney Shale case study in southern Oklahoma, USA. J. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 96, 104296 (2021).

Allan Katende, J. et al. Experimental flow-through a single fracture with monolayer proppant at reservoir conditions: a case study on Caney Shale, Southwest Oklahoma. USA J. Energy. 273, 127181 (2023).

Allan Katende, C. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation of proppant embedment and conductivity reduction within a fracture in the Caney Shale, Southern Oklahoma. USA J. Fuel, 127571. (2023).

Estrada, J. M. & Bhamidimarri, R. A review of the issues and treatment options for wastewater from shale gas extraction by hydraulic fracturing. Fuel. 182, 292–303 (2016).

Zhang, D. & Yang, T. Environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing in shale gas development in the USA. Pet. Explor. Dev. 42 (6), 876–883 (2015).

Qu, H. Y. et al. Impact of thermal processes on CO2 injectivity into a coal seam. IOP Conference Series: J. Materials Science and Engineering, 10, 012090. (2010).

Yin, H. et al. Experimental study of the effects of sub-and super-critical CO2 saturation on the mechanical characteristics of organic-rich shales. J. Energy. 132, 84–95 (2017).

Baoping, X. I. et al. Experimental study on permeability characteristics and its evolution of granite after high temperature. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40 (S1), 2716–2723 (2021). (in Chinese).

Cho, Y., Apaydin, O. G. & Ozkan, E. Pressure-dependent naturalfracture permeability in shale and its effect on shale-gas well production. SPE Reserv. Eval Eng. 16, 216–228 (2013).

Zhou, H. W., Zhang, L., Wang, X. Y., Rong, T. L. & Wang, L. J. Effects of matrix-fracture interaction and creep deformation on permeability evolution of deep coal. J. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 127, 104236 (2020).

Davudov, D. & Moghanloo, R. G. Impact of pore compressibility and connectivity loss on shale permeability. J. Int. J. Coal Geol. 187, 98–113 (2018).

Tan, Y. et al. Experimental study of impact of anisotropy and heterogeneity on gas flow in coal. Part. II: Permeability J. Fuel. 230, 397–409 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Swelling effect on coal micro structure and associated permeability reduction. J. Fuel. 182, 568–576 (2016).

Heller, R. & Zoback, M. Adsorption of methane and CO2on gas shale and pure mineral samples.J. J. Unconv. Oil Gas Resour. 8, 14–24 (2014).

Chen, T., Feng, X. T. & Pan, Z. Experimental study on kinetic swelling of organic-rich shale in CO2,CH4 and N2.J. J. ofNatural Gas Sci. Eng. 55, 406–417 (2018).

Sang, G., Elsworth, D., Liu, S. & Harpalani, S. Characterization of swelling modulus and effective stress coefficient accommodating sorption-induced swelling in coal. J. Energy Fuels. 31, 8843–8851 (2017).

Day, S., Fry, R. & Sakurovs, R. Swelling of coals in CO2, methane and their mixtures. J. Int. J. Coal Geol. 93 (1), 40–48 (2012).

Niu, Q., Cao, L., Sang, S., Zhou, X. & Wang, Z. Anisotropic adsorption swelling and permeability characteristics with injecting CO2 in coal. J. Energy Fuels. 32 (2), 1979–1991 (2018).

Cui, X. & Bustin, R. M. Volumetric strain associated with methane desorption and its impact on coalbed gas production from deep coal seams. J. AAPG Bull. 89, 1181–1202 (2005).

Cui, X., Bustin, R. M. & Chikatamarla, L. Adsorption induced coal swelling and stress: implications for methane production and acid gas sequestration into coal seams. J. J. Geophys. Research: Solid Earth. 112, B10202 (2007).

Zang, J. & Wang, K. Gas sorption induced coal swelling kinetics and its effects on coal permeability evolution: model development and analysis. J. Fuel. 189, 164–177 (2017).

Liu, H. H. & Rutqvist, J. A new coal-permeability model: internal swelling stress and fracture-matrix interaction. Transp. Porous Media. 82 (1), 157–171 (2010).

Connell, L. D., Lu, M. & Pan, Z. An analytical coal permeability model for triaxial strain and stress conditions.J. Int. J. Coal Geol. 84 (2), 103–114 (2010).

NIU, Y. et al. Coal permeability gas slippage linked to permeability rebound. J. Fuel. 215, 844–852 (2018).

FATHI, E., TINNI, A. & AKKUTLU I. J Correction to Klinkenberg slip the ory for gas flow in nano capillaries. J. Int. J. Coal Geol. 103, 51–59 (2012).

LIU, C. et al. Effective stress effect and slippage effect of gas migration in deep coal reservoirs.J. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 155, 105142 (2022).

Moghadam A, Chalaturnyk R. Expansion of the Klinkenberg’s slippage equation to low permeability porous mediaJ. Int. J. Coal Geol., 123: 2–9. (2014).

CUI, X., BUSTIN AND, A. M. M. & R. M. BUSTIN Measurements of gas permeability and diffusivity of tight reservoir rocks: different approaches and their applications. J. Geofluids. 9, 208–223 (2009).

Li, Z. et al. Using pressure pulse decay experiments and a novel multi-physics shale transport model to study the role of Klinkenberg effect and effective stress on the apparent permeability of shales. J. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 189, 107010 (2020).

Zehao Yang, Q. et al. A modified pressure-pulse decay method for determining permeabilities of tight reservoir cores. J. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 27, 236–246 (2015).

Zhao, Y. et al. Experimental study of adsorption effects on shale permeability. J. Nat. Resour. Res. 28 (4), 1575–1586 (2019).

Brace, W. F., Walsh, J. B. & Frangos, W. T. Permeability of granite under high pressure. J. Geophys. Res. 73, 2225–2236 (1968).

Lin, W. Compressible Fluid Flow Through Rocks of Variable Permeability. Mallon, A.J., Swarbrick, R.E., 2008. How Should Permeability be Measured in Fine-grained Lithologies? Evidence from the Chalk. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. (1977).

Zehao Yang, Q. & Sang etc. A modified pressure-pulse decay method for determining permeabilities of tight reservoir cores. J. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering.27, 236–246 (2015).

Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusionpp. 56–59 (Clarendon, 1975).

Loebenstein, W. V. Calculations and comparisons of nonideal gas corrections for use in gas adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 3, 397–400 (1971).

Mahmoud, M. Development of a new correlation of gas compressibility factor (Z-factor) for high pressure gas reservoirs. J. Energy Res. Technol. 136, 12903 (2013).

Heidaryan, E., Salarabadi, A. & Moghadasi, J. A novel correlation approach for prediction of natural gas compressibility factor. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 19, 189–192 (2010).

Lee, A. L., Gonzalez, M. H. & Eakin, B. E. The viscosity of natural gases. J. Pet. Technol. 18, 997–1000 (1966).

Ranathunga, A. S. et al. Super-critical CO2fow behaviour in low rank coal: a meso-scale experimental study. J. Utiliz. 20, 1–13 (2017).

Gautam Rajeeb, Wong Ron, C. K. Transversely isotropic stiffness parameters and their measurement in Colorado shale. J.Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 2006, 43(12):1290–1305. (2006).

Sakurovs, R. et al. Application of a Modified Dubinin-Radushkevich equation to adsorption of gases by coals under supercritical conditions. J. Energy Fuels. 21, 992–997 (2007).

Ao Xiang, L. et al. Deformation properties of shale by sorbing CO2. J. J. China Coal Soc. 40 (12), 2893–2899 (2015).

Liu, T., Lin, B. & Yang, W. Impact of matrix – fracture interactions on coal permeability: model development and analysis. J. Fuel. 207, 522–532 (2017).

Gao, Q. et al. Effect of shale matrix heterogeneity on gas transport during production: a microscopic investigation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 201, 108526 (2021).

MOGHADAM, A. & CHALATURNYK R Expansion of the Klinkenberg ‘s slippage equation to low permeability porous media.J. Internatio- Nal. J. Coal Geol. 123, 2–9 (2014).

Moghadam, A. A. & Chalaturnyk, R. Analytical and experimental investigations of gas-flow regimes in shales considering the influence of mean effective stress. J. SPE J. 21, 557–572 (2016).

Lu, S., Cheng, Y. & Li, W. Model development and analysis of the evolution of coal permeability under different boundary conditions. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 31, 129–138 (2016).

HELLER, R., VERMYLEN, J. & ZOBACK M Experimental investigation of matrix permeability of gas shales. J. AAPG Bull. 98 (5), 975–995 (2014).

Jun, W. A. N. G. et al. Effect of effective stress and slippage on deep shale gas seepage, 12-4461-12 (Chinese) (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Second-order correction of Klinkenberg equation and its experimental verification on gas shale with respect to anisotropic stress. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 89, 103880 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51974147, 51974186, 52204218) and Department of Education of Liaoning Province (No. LJ232410147051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wen Bo Zhai is responsible for the writing and experiment of the article.Di Wu、Xiaochun Xiao and Xin Ding provided fund support.Xueying Liuwas responsible for the revision of the text.Feng Miao and Xin Tong Chen are responsible for data processing and experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

I certify that this manuscript is original and has not been published and will not be submitted elsewhere for publication. And the study is not split up into several parts to increase the quantity of submissions and submitted to various journals or to one journal over time. No data have been fabricated or manipulated (including images) to support your conclusions. No data, text, or theories by others are presented as if they were our own. Te submission has been received explicitly from all co-authors. And authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhai, W., Wu, D., Liu, X. et al. The seepage model for CO2 in Shale considering dynamic slippage, effective stress and gas adsorption. Sci Rep 14, 30697 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78533-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78533-w