Abstract

Heart failure (HF) constitutes a substantial burden on healthcare systems worldwide, contributing to elevated rates of mortality and morbidity. Iron deficiency (ID), both with and without concurrent anemia, has been identified in up to half of all patients with CHF and is associated with an increased risk of HF exacerbations, higher rates of hospitalization, and diminished quality of life. However, data from resource-limited settings remain limited. In this study, we reviewed 108 adult Yemeni patients with HF who also had concomitant ID, defined as serum ferritin concentrations of < 100 ng/mL or 100–299 ng/mL with transferrin saturation < 20%. The prevalence of ID among HF patients was determined, and independent predictors of ID were assessed using univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Anemia was present in 64 (59.3%), ID was observed in 65 (60.2%), and both anemia and ID were concurrently present in 44 (40.7%) patients. The mean ejection fraction among the study cohort was 34.2 ± 6.3%. Multivariate regression analysis identified New York Heart Association class III (OR: 4.46; 95% CI: 1.65–12.90, p = 0.004), presence of anemia (OR: 3.95; 95% CI: 1.51–11.23, p = 0.007), and an EF < 30% (OR: 9.42; 95% CI: 1.97–54.64, p = 0.007) as independent predictors of ID. These findings highlight the potential under-recognition of ID in patients with congestive HF, suggesting the need for routine assessment of iron status in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF), which affects 1–2% of the general population, is a leading cause of death, morbidity, and poor quality of life1. The overall prevalence of HF is estimated to grow drastically on a global level, placing a tremendous burden on patients, their families, and healthcare systems2. In addition to increased mortality, HF patients are prone to recurrent hospitalizations, worse functional performance, and poor quality of life3. Iron deficiency (ID), with or without concomitant anemia, has been reported extensively in HF patients, affecting up to 50% of stable patients, with a higher prevalence reaching 80% for decompensated patients4,5. Notably, ID has been associated with poor functional capacity, increased length of hospitalization, and increased mortality in HF patients6,7,8.

The pathogenesis of ID in HF appears to be multifactorial, involving a persistent inflammatory state that leads to iron sequestration and impaired mobilization, along with reduced bowel absorption in advanced stages of HF9,10. The critical cellular role of iron in aerobic respiration, particularly in energy-demanding cardiac myocytes, highlights the clinical significance of ID in HF patients11. Furthermore, ID has been associated with adverse cardiac remodeling, which is particularly detrimental in cases of iron deficiency anemia (IDA), leading to impaired cardiac function and a worsening of clinical status12,13,14.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommend baseline anemia evaluations for HF patients in outpatient settings, as well as pre-discharge assessments of iron stores for patients hospitalized due to HF exacerbations15,16. The prevalence of ID anemia has been reported to exceed 80% among children and pregnant women in Yemen17. However, there is limited knowledge regarding the incidence of ID among HF patients in Yemen. The present study aims to evaluate the prevalence and independent predictors of ID in Yemeni patients with HF in a resource-limited setting.

Result

Basic characteristics

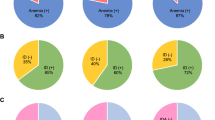

The patient demographic characteristics are mentioned in Table 1. The mean age was 60.4 ± 14.9 years (range 25–100 years), and 34 (31.5%) were older than 70. Most patients were male (n = 77, 71.3%). Anemia was represented in 64 (59.3%) cases, and ID was represented in 65 (60.2%) cases, while both anemia and ID were seen in 44 (40.7%) cases. The mean EF was 34.2 ± 6.3%, and EF was between 30% and 40% in 62 (57.4%) cases. Current smoking and Khat chewing were seen in 51 (47.2%) and 88 (81.5%) cases, respectively. The comorbidities were hypertension in 63 (58.3%), diabetes in 30 (27.8%), coronary artery disease in 55 (50.9%), chronic renal failure in 15 (13.9%), and liver disease in 4 (370%) of cases. History of cardiac intervention includes PCI in 29 (26.9%) and CABG in 4 (3.7%) cases. New York Heart Association (NYHA) class 3 was represented in 76 (70.4%), while NYHA-2 was represented in 32 (29.6%). Previous blood transfusion was reported in 11 (10.2%) cases.

Laboratory findings

The mean hemoglobulin level was 11.9 ± 2.6 g/dL (Range 6.7–18.0 g/dL). The mean iron level was 78.2 ± 44.1 µg/L (Range 2.7–297 µg/L). The mean ferritin level was 128.5 ± 133.3 µg/L (8.8–925 µg/L). The main laboratory findings are mentioned in Table 2.

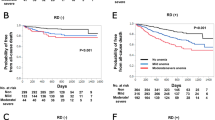

Independent predictors of iron deficiency

In univariate analysis, factors including previous blood transfusion (p = 0.043), low Ejection fraction (%) (p = 0.001), anemia (p = 0.046), and NYHA class (p = 0.001) were associated with ID and were statistically significant (Table 1). However, in regression analysis, only NYHA class 3 (OR: 4.46; 95% CI: 1.65–12.90, p = 0.004), anemia (OR: 3.95; 95 CI%: 1.51–11.23, p = 0.007), and EF < 30% (OR: 9.42; 95% CI: 1.97–54.64, p = 0.007) were independent predictors of ID and statistically significant (Table 3).

Discussion

The pathogenesis of iron deficiency in HF is complex, involving several cellular alterations that lead to structural changes and functional dysfunction18. The poor nutritional status of HF patients, which tends to worsen as HF progresses, along with reduced iron absorption due to gut congestion, contributes to this deficiency19. Additionally, HF represents an inflammatory state characterized by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, which can result in iron trapping within the reticuloendothelial system. This has been linked to decreased myocardial iron stores and impaired mitochondrial function in HF patients. Iron deficiency is also associated with reduced exercise endurance, poor quality of life, and increased morbidity and mortality, even without anemia20,21.

The mean age of our patients was 60.4 ± 14.9 years. While males were disproportionately presented (71.3%), females had a relatively higher prevalence of ID (64.5%) compared to males (58.4%). The difference was not statistically significant; however, it is consistent with prior reports that identified female gender as an independent predictor of ID among HF patients1,22,23. This is consistent with national and international reports that highlighted the higher incidence of ID among females in the settings of menstruation, pregnancy, and breastfeeding5,24. More evidence suggests different hepcidin expressions, which might influence iron storage and transport25. This study found anemia in 64 patients (59.3%), while anemia and ID were present in 44 (40.7%). Similar to our result, Sharma et al. found that 76% of HF patients had ID, with anemia present in 51.3%, and a large percentage of patients (24.7%) had ID without anemia1. These findings highlight the possibility of ID even with normal hemoglobin levels and the need for comprehensive iron level assessment8. In support of the prior findings, Yeo et al. emphasized assessing functional ID, which correlates with HF symptoms independent of EF26.

A sub-analysis of our patient cohort demonstrated a higher prevalence of ID among those without concurrent anemia (60.2%). Previous studies have reported varying prevalence rates, ranging from 37 to 75.3%, with lower rates, ranging from 30 to 50%, observed in developed countries22,27. Conversely, higher rates have been documented in India. Singh et al. reported that, among 204 HF patients, the prevalence of absolute ID was 83.3%, functional ID 5.3%, and total ID 88.7%.22 This variation may be attributable to differences in dietary patterns, healthcare access, and treatment practices. Nonetheless, the retrospective design of these studies limits their generalizability and suggests that differences in baseline patient characteristics and comorbid conditions may contribute to these findings.

In this study, worse functional status, as indicated by NYHA ≥ class 3, and an EF < 30% were observed in 76 (70.4%) and 23 (21.3%) HF patients with ID, respectively. Furthermore, these factors emerged as independent predictors of ID in HF patients, with statistically significant associations observed in the regression analysis. Our findings align with previous studies, such as those by Yeo et al., who also reported a correlation between worse functional status, low EF, and ID in HF patients26. Despite these observations, ID remains prevalent even among patients with HF with preserved EF (21.3%). Unlike individuals with HF and reduced EF, those with preserved EF have not been shown to exhibit downregulation of the myocardial transferrin receptor. In cases of functional ID, activation of the cardiac transferrin receptor in patients with preserved EF suggests the persistence of compensatory mechanisms28.

Although comorbidities did not differ substantially across the groups we studied, individuals with ID had a higher prevalence of hypertension (35% vs. 28%) and diabetes (20% vs. 10%) compared to those without ID. Both hypertension and diabetes were shown to be independently associated with cardiovascular disease, contributing to microvascular and macrovascular complications through mechanisms involving oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction29. These conditions are also linked to impaired renal function, which can exacerbate anemia and lead to iron sequestration30. These factors may also worsen cardiac elasticity and stiffness28,31. However, in the absence of anemia, we could not establish a significant role for ID in contributing to left ventricular stiffness. This could be attributed, in part, to the relatively younger patient population and the small sample size in our study.

Few studies have identified ID as an independent predictor of outcomes in HF, and the current evidence remains inconsistent. Observational studies have demonstrated unfavorable outcomes associated with ID, independent of anemia5,32,33. However, a recent observational study by Parikh et al. found no association between ID and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality. However, this study did not exclude heart failure with preserved ejection fraction34. Data from prospective clinical trials have also failed to demonstrate mortality benefits. For example, the administration of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose showed no cardiovascular mortality benefit35.

Similarly, the IRONMAN trial reported inconclusive findings regarding the role of iron in improving the quality of life for HF patients, and no benefit was observed in terms of hospitalization reduction36. While these studies were conducted among hospitalized patients, who are generally sicker, data from the HEART-FID trial, conducted among ambulatory HF patients, also failed to show a mortality benefit or reduced hospitalization rates37. In contrast, a meta-analysis by Ponikowski et al. found that ferric carboxymaltose was associated with reduced hospitalization rates38. European guidelines currently recommend frequent assessment of iron status and replenishment therapy to improve the quality of life in HF patients39,40.

The causes of anemia in HF patients present a clinical challenge. In addition to ID, other potential causes of anemia include chronic inflammation, elevated erythropoietin levels, increased renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activity, sodium and water retention due to RAAS activation, and the use of medications such as beta-blockers and digoxin. Therefore, heart failure patients with low hemoglobin but without ID should be investigated with the same urgency as those with confirmed ID anemia41. In this study, anemia without ID was presented in 20 patients (18.5%). However, due to the study’s retrospective nature, data on the primary causes of anemia without ID were not collected, which is attributed to limited documentation or incomplete work-up for such patients. Future prospective studies are needed to explore the underlying causes of anemia without ID.

Clinical implication of iron deficiency

Low iron levels in HF patients lead to diminished exercise tolerance, reduced peak oxygen consumption, and increased ventilatory response. Aerobic capacity and ventilatory response are correlated with TSAT and ferritin. ID, despite its role in reducing exercise capacity and quality of life, has been linked to increased hospitalization and mortality rates, regardless of anemia. Thus, all HF patients should be screened for ID and receive promoted treatment20,21,41,42. Other effective measures include mass iron food fortification, targeted iron supplementation programs/interventions, hookworm and malaria management, and public education regarding iron-rich plant and animal-based meals20.

Study limitation

This single-center study is limited by its reliance on secondary data, which introduces potential variability in data quality due to inconsistencies in documentation, data integrity, and record-keeping practices. Additionally, the retrospective design may introduce inherent biases, and excluding records with incomplete data could lead to selection bias. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size limits the scope for robust statistical analysis. Moreover, the mortality rate, the effects of iron supplementation, and the impact of ID on mortality were not evaluated due to a lack of available data. There were also technical limitations related to the methods used for defining ID and ejection fraction (EF). Left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction was assessed using the Teichholtz formula, which has inherent limitations in sensitivity, as the calculation of LV volumes and EF is based on LV dimensions in end-diastole and end-systole, relying on assumptions that may not be reliable in cases of distorted LV geometry. Despite these limitations, this study represents the first report on the prevalence and impact of ID in heart failure patients in Yemen. Our findings highlight the need for further research to understand better the unique challenges and opportunities for treatment in resource-constrained settings.

Conclusion

Our results found that ID is standard in HF patients, with ejection fraction < 30%, anemia, and NYHA class 3 being independent predictors of ID. Routine assessment of iron status in chronic HF patients and those hospitalized with worsening HF is crucial—even in patients with normal hemoglobin levels. Further studies are warranted to evaluate this population’s potential long-term benefits of iron supplementation.

Materials and methods

Study design

A retrospective cross-sectional study consisted of 108 Adult Yemeni patients with heart failure (HF) who had been admitted from Jun 2021 to Sept 2022 to Al-Thorah General Hospital (Ibb University-affiliated Hospital).

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients who were ≥ 18 years of age, clinically diagnosed with HF, and recently admitted for HF progressive symptoms in our hospital were included. Diagnosis of HF was established based on validated clinical criteria from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the ESC guidelines for the diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF), and the Framingham criteria43,44,45.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with comorbid noncardiac conditions causing ID or anemia, including upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding, malignancy, end-stage renal failure [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 15 ml/ min)], patients with congenital heart disease, or who would be expected to have a different natural history than a ‘typical’ HF patient were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using G Power version 3 software and selected by setting a 95% confidence interval, 80% power, and 5% alpha error based on a previously reported prevalence and spectrum of ID in HF patients in South Rajasthan by Sharma et al1.. The sample size was determined to be 90 patients in the first stage. Taking into account 15% attrition, in the end, at least 100 samples were required in this study.

Data collection

Patient demographic characteristics include age (categorized as ≤ 70 years and > 70 years), gender, history of Khat chewing, and current smoking status. Comorbidities include a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, chronic liver disease, duration of illness (categorized as < six months and > six months), previous blood transfusion, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and history of cardiac intervention such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The laboratory findings include Red Blood Cell count (RBC), Hemoglobin (HB), Hematocrit (Hct), Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC), Ferritin level, Iron level, triglyceride, and cholesterol levels and transthoracic echocardiography findings (Fig. 1).

Echocardiographic aspects of dilated cardiomyopathy. (A): Parasternal long-axis view: dilated left atrium and left ventricle in diastole. (B): Apical 4 chamber view: dilated left ventricle, dilated left atrium, significant secondary mitral regurgitation flow with Coanda effect. (C): Apical 4 chamber view: dilated cardiomyopathy with tricuspid regurgitation flow. (D): Apical 4 chamber view: global hypokinesia suggesting ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.

Ejection Fraction (EF) was obtained via echocardiography, and patients were categorized as > 40%, between 40 and 30%, and < 30%.22Iron deficiency was defined as ferritin levels of < 100 µg/L or 100–299 µg/L with transferrin saturation (TSAT) of < 20%. Anemia was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as hemoglobin of < 13 g/dL in males and < 12 g/dL in females33. Renal dysfunction was diagnosed with a GFR of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Diabetes mellitus was defined as glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) > 6.4% if the patient is actively taking anti-hypoglycemic agent(s) or is on insulin therapy. In addition, the patients’ charts were reviewed for any previous diagnosis or treatment for hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or liver diseases. Functional status was classified according to the NYHA functional classification system (Class I-IV). Data were collected through independent chart reviews. The collected data were thoroughly assessed for accuracy, completeness, and consistency. In cases where contradictory or missing information was identified, the charts were reviewed and reevaluated to ensure data quality.

Study outcome

The primary outcome was to report the prevalence of iron deficiency, and the secondary outcome was to find the independent predictors of ID among admitted patients with heart failure.

Statistical analysis

Before statistical analysis, the normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. We utilized mean ± SD representations for numerical data, and for categorical ones, we opted for frequency (percentage) portrayals. We determined statistical variances for numeric data via an independent t-test, and to discern significant associations between qualitative variables, we implemented the chi-square test. In instances where the expected frequency was restricted, Fisher’s exact test was deemed appropriate. Logistic regression was performed with variables for any association to obtain odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The logistic regression models included variables with P ≤ 0.05 in univariable models. Statistical significance was considered with a P-value under 0.05. The data was processed using the software SPSS (IBM SPSS, version 22, Armonk, New York: IBM Corp).

Ethics statement

The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration’s principles, and Ibb University’s ethics board approved this research (Code number: IBBUNI.AC.YEM.2023.117). Participating patients consented to and signed an informed consent form for the gathering of data from their medical records, as well as the publishing of their medical information, at the time of registration.

Data availability

Underlying dataMendeley Data: Abdullah, Mohammed; abdo, Basheer; ahmed, Faisal (2024), “Prevalence and Independent Predictors of Iron Deficiency in Yemeni Patients with Heart Failure: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/czgnys3dbn.1, https://data.mendeley.com/drafts/czgnys3dbn. Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

References

Sharma, S. K. et al. Prevalence and spectrum of iron deficiency in heart failure patients in south Rajasthan. Indian Heart J. 68, 493–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2015.10.387 (2016).

Sharma, Y. P. et al. Anemia in heart failure: still an unsolved enigma. Egypt. Heart J. 73 https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-021-00200-6 (2021).

Grote Beverborg, N., van Veldhuisen, D. J. & van der Meer, P. Anemia in Heart failure: still relevant? JACC Heart Fail. 6, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.08.023 (2018).

Manceau, H. et al. Neglected comorbidity of Chronic Heart failure: Iron Deficiency. Nutrients. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153214 (2022).

Rangel, I. et al. Iron deficiency status irrespective of anemia: a predictor of unfavorable outcome in chronic heart failure patients. Cardiology. 128, 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358377 (2014).

AlAayedi, K. An audit of Iron Deficiency in Hospitalised Heart failure patients: a commonly neglected Comorbidity. Cureus. 15, e41515. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.41515 (2023).

Del Pinto, R. & Ferri, C. Iron deficiency in heart failure: diagnosis and clinical implications. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 24, I96–i99. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suac080 (2022).

Yang, T. Y. et al. Anemia warrants treatment to improve survival in patients with heart failure receiving sacubitril-valsartan. Sci. Rep. 12, 8186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11886-2 (2022).

Naito, Y. et al. Impaired expression of duodenal iron transporters in Dahl salt-sensitive heart failure rats. J. Hypertens. 29, 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283434784 (2011).

Markousis-Mavrogenis, G. et al. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21, 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1482 (2019).

Beavers, C. J. et al. Iron Deficiency in Heart failure: a Scientific Statement from the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 29, 1059–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.03.025 (2023).

Melenovsky, V. et al. Myocardial iron content and mitochondrial function in human heart failure: a direct tissue analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 19, 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.640 (2017).

Augusto, S. N. & Martens, P. Heart failure-related Iron Deficiency Anemia Pathophysiology and Laboratory diagnosis. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 20, 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-023-00623-z (2023).

Simon, S. et al. Audit of the prevalence and investigation of iron deficiency anaemia in patients with heart failure in hospital practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 96, 206–211. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-136867 (2020).

McDonagh, T. A. et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 42, 3599–3726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368 (2021).

Heidenreich, P. A. et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the management of Heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice guidelines. Circulation. 145, e876–e894. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000001062 (2022).

Al-Alimi, A. A., Bashanfer, S. & Morish, M. A. Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia among University students in Hodeida Province, Yemen. Anemia. 2018 (4157876). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4157876 (2018).

Alnuwaysir, R. I. S., Hoes, M. F., van Veldhuisen, D. J. & van der Meer, P. Grote Beverborg, N. Iron Deficiency in Heart failure: mechanisms and pathophysiology. J. Clin. Med. 11, 125 (2022).

Richards, T. et al. Questions and answers on iron deficiency treatment selection and the use of intravenous iron in routine clinical practice. Ann. Med. 53, 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2020.1867323 (2021).

Rizzo, C., Carbonara, R., Ruggieri, R., Passantino, A. & Scrutinio, D. Iron Deficiency: a new target for patients with heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 709872. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.709872 (2021).

von Haehling, S. et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of iron deficiency and anaemia among outpatients with chronic heart failure: the PrEP Registry. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 106, 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-016-1073-y (2017).

Singh, B. et al. Iron deficiency in patients of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 78, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2022.04.013 (2022).

Arora, H., Sawhney, J. P. S., Mehta, A. & Mohanty, A. Anemia profile in patients with congestive heart failure a hospital based observational study. Indian Heart J. 70 (Suppl 3), S101–s104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2018.06.017 (2018).

Al-Zendani, A. et al. Acute heart failure in Yemen. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown). 20, 156–158. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0000000000000748 (2019).

Harrison-Findik, D. D. Gender-related variations in iron metabolism and liver diseases. World J. Hepatol. 2, 302–310. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v2.i8.302 (2010).

Yeo, T. J. et al. PT081 functional iron deficiency in heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Global Heart. 9, e181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1873 (2014).

Sun, H. et al. Iron deficiency: prevalence, mortality risk, and dietary relationships in general and heart failure populations. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1342686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1342686 (2024).

Kasner, M. et al. Functional iron deficiency and diastolic function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 4652–4657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.185 (2013).

Petrie, J. R., Guzik, T. J., Touyz, R. M. & Diabetes Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 34, 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005 (2018).

Van Buren, P. N. & Toto, R. Hypertension in diabetic nephropathy: epidemiology, mechanisms, and management. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 18, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2010.10.003 (2011).

Kim, Y. R., Pyun, W. B. & Shin, G. J. Relation of anemia to echocardiographically estimated left ventricular filling pressure in hypertensive patients over 50 year-old. J. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 18, 86–90. https://doi.org/10.4250/jcu.2010.18.3.86 (2010).

Okonko, D. O., Mandal, A. K., Missouris, C. G. & Poole-Wilson, P. A. Disordered iron homeostasis in chronic heart failure: prevalence, predictors, and relation to anemia, exercise capacity, and survival. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 1241–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.040 (2011).

Jankowska, E. A. et al. Iron deficiency: an ominous sign in patients with systolic chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 31, 1872–1880. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq158 (2010).

Parikh, A., Natarajan, S., Lipsitz, S. R. & Katz, S. D. Iron deficiency in community-dwelling US adults with self-reported heart failure in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III: prevalence and associations with anemia and inflammation. Circ. Heart Fail. 4, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.111.960906 (2011).

Ponikowski, P. et al. Ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency at discharge after acute heart failure: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 396, 1895–1904. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32339-4 (2020).

Kalra, P. R. et al. Intravenous ferric derisomaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency in the UK (IRONMAN): an investigator-initiated, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet. 400, 2199–2209. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02083-9 (2022).

Mentz, R. J. et al. Ferric Carboxymaltose in Heart failure with Iron Deficiency. N Engl. J. Med. 389, 975–986. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2304968 (2023).

Ponikowski, P. et al. Efficacy of ferric carboxymaltose in heart failure with iron deficiency: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 44, 5077–5091. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad586 (2023).

Okonko, D. O. et al. Effect of intravenous iron sucrose on exercise tolerance in anemic and nonanemic patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure and iron deficiency FERRIC-HF: a randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.036 (2008).

Toblli, J. E., Lombraña, A., Duarte, P. & Di Gennaro, F. Intravenous iron reduces NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide in anemic patients with chronic heart failure and renal insufficiency. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.029 (2007).

Siddiqui, S. W. et al. Anemia and heart failure: a narrative review. Cureus. 14, e27167. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27167 (2022).

Paterek, A. et al. Beneficial effects of intravenous iron therapy in a rat model of heart failure with preserved systemic iron status but depleted intracellular cardiac stores. Sci. Rep. 8, 15758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33277-2 (2018).

McMurray, J. J. et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 33, 1787–1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104 (2012).

Paulus, W. J. et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the heart failure and Echocardiography associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 28, 2539–2550. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037 (2007).

McKee, P. A., Castelli, W. P., McNamara, P. M. & Kannel, W. B. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl. J. Med. 285, 1441–1446. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197112232852601 (1971).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and B.A. conceived and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; F.A., K.A., N.A., and M.B. conducted the data analysis; F.A., M.A., B.A., and K.A. provided insights into the study’s conceptualization and extensively reviewed all manuscript drafts. All the authors read and provided significant inputs into all manuscript drafts, agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and approved the final version of this manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by Ibb University’s Ethics Committee (Code number: IBBUNI.AC.YEM.2023.117).

Consent to participate/Consent to publish

All patients provided written informed consent to be involved in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdullah, M., Abdo, B., Ahmed, F. et al. Prevalence and independent predictors of Iron deficiency in Yemeni patients with congestive heart failure: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 28901 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78556-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78556-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Iron Deficiency as a Modifiable Risk Factor in Heart Failure: Evidence and Recommendations

American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs (2025)