Abstract

Leachate from municipal solid waste landfills poses a significant threat to aquatic ecosystems due to poor management practices. This study evaluated thirty leachate samples from Iranian metropolises using the Leachate Pollution Index (LPI). Various parameters, including BOD₅, COD, TDS, pH, EC, heavy metals, turbidity, PAHs, phthalates, and humic acid, were analysed. The BOD₅ levels ranged from 350 to 20,000 mg/L, and the COD levels ranged from 2,000 to 90,000 mg/L. The TDS content varied between 14.7 and 67 g/L, while the turbidity ranged from 15 to 186 NTU. Heavy metals were present but within standard limits. The phthalate concentrations ranged from 6 to 150.8 mg/L, and the humic acid concentrations ranged from 135 to 2,200 mg/L. Naphthalene was the most frequent hydrocarbon detected. The LPIs were less than 30 for all the samples, with the highest in Ahvaz and the lowest in the treated samples from Tehran. This study highlights the presence of persistent organic and hazardous contaminants in Iran’s municipal landfills, emphasizing the need for effective leachate treatment and improved waste management practices. Enhanced final disposal methods, increased waste recovery, and improved solid residue separation are crucial for preventing further leachate production and environmental contamination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In urban areas, there has been a substantial surge in the volume of municipal solid waste (MSW), largely driven by the expanding population and the rapid progression of urban development1. Leachate, a liquid produced from waste, is a serious pollutant that impacts natural resources, including soil and water, thereby affecting human health2,3. Leachate, which percolates through waste material in landfills and accumulates at the base, contains a wide array of chemical compounds, both biodegradable and nonbiodegradable. These contaminants include a wide range of organic compounds. Among them are heavy metals and aromatic hydrocarbons, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and phenolics2. Chlorinated aliphatic compounds and long-chain alkanes are also present. Additionally, fatty acids, nonylphenol ethoxycarboxylate acids, pesticides, and emerging contaminants of concern, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs), can be found4,5. Persistent organic pollutants such as PCBs and dioxins have also been detected. The presence of these compounds contributes to the complex and polluting nature of leachate, posing significant risks to the environment and public health5,6.

The characteristics and amount of leachate are influenced by numerous factors, including the waste composition and moisture content, geographical conditions, landfill age, landfill temperature, and chemical and biochemical processes that drive the breakdown of waste materials5,7. Numerous efforts have been made to characterize the quality of leachate and assess its impact on the environment8. Typically, leachate characterization involves the use of traditional parameters, such as pH, electrical conductivity (EC), total organic carbon (TOC), Zn, Cu, Cd, Pb, Cr, Hg, and PAHs9. The primary environmental concern regarding leachate is its potential to degrade the quality of surface water and groundwater, subsequently endangering aquatic ecosystems and human health7. The majority of the reported compounds are recognized as part of the current list of 126 priority pollutants outlined by the US EPA and are quite refractory to biodegradation5. Therefore, the correct and principled management of leachate is a critical concern in landfill design and operation. Many nations worldwide are strengthening their regulations on landfill leachate management and disposal, driven by the environmental concerns associated with leachate7,8. Nevertheless, instances of mismanagement in waste disposal facilities persist, particularly in developing countries. Factors such as poverty, insufficient funding, and lack of expertise contribute to inadequate leachate management in these regions9. The International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) has documented over 750 deaths worldwide that are directly linked to poor landfill operations and management10. In some countries, inadequate or nonexistent regulations for leachate disposal stem from a lack of sufficient information about leachate characteristics10. Hence, it is essential to accurately comprehend the quantity, quality, and pollution risks associated with landfill leachate to make informed decisions regarding suitable management and treatment methods9.

Previous research in Iran has mostly focused on localized and limited studies regarding the characteristics of leachate in landfill sites. For example, studies conducted in cities like Mashhad, Tehran, and Isfahan revealed that leachate contains high concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and chromium, and in some cases, groundwater quality near these sites has been adversely affected9,11. Other research has examined leachate quality before and after treatment in Tehran’s landfills, indicating a relative reduction in pollution post-treatment. However, comprehensive studies that evaluate leachate characteristics across multiple major cities in a standardized manner remain limited. This research aims to fill that gap by providing updated data on leachate across various Iranian metropolises, including Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Tabriz, and Ahvaz. The motivation for this study lies in the need for a more thorough understanding of leachate composition across these regions. Its originality is reflected in the simultaneous analysis of leachate from multiple landfill sites and the use of the leachate pollution index (LPI) for a comprehensive evaluation, which can inform more effective waste management policies.

The quantification of leachate contamination potential can be employed to assess the performance of landfills, aiding in their optimal operation for efficiency12. Additionally, this quantification serves as a crucial step in landfill management, offering numerous benefits to the environment. To prevent environmental damage and comprehend the risks associated with landfills, a precise understanding of leachate pollution is necessary13. Thus, it is very important to have sufficient information about leachate quality for its management and control.

The leachate pollution index (LPI) serves as a valuable tool for assessing the pollution potential of landfill leachate. By analyzing various physical and chemical parameters, the LPI calculates a single value that indicates the range of contamination risks associated with leachate14. Essentially, it provides a rating that reflects the likelihood and potential severity of leachate polluting groundwater sources. The detection and analytical procedures for hazardous materials, as well as the analysis of the physicochemical properties of leachate, are top priorities in environmental monitoring and post-closure care. It is essential to employ an appropriate measurement system to assess the potential contamination of soils surrounding landfill sites and groundwater aquifers caused by leachate from landfills15.

To date, limited research has been conducted on the characteristics and quality of landfill leachate in Iran11. Thus, the objective of this study was to examine the physicochemical parameters, heavy metals, and leachate pollution indices (LPIs) of leachates from landfills in Iranian metropolises (Mashhad, Sanandaj, Tehran (before and after treatment plant), Hamedan, Isfahan, Ahwaz, Qazvin, Rasht, and Tabriz). This investigation is intended to inform authorities and stakeholders, urging heightened attention to this critical issue.

Materials and methods

Selected landfill areas

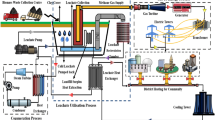

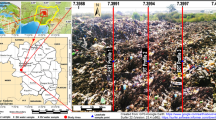

Leachate samples were collected from landfills in various Iranian metropolises in coordination with responsible waste management organizations. The selection of cities for this study involved three key criteria: their geographic distribution across Iran, the presence of an active landfill within the city limits, and the existence of infrastructure for leachate drainage. Additionally, the selected cities were required to have a significant population size and be the capital of their respective provinces. Based on these criteria, ten cities in Iran were selected: Isfahan, Hamedan, Tabriz, Tehran(before and after treatment plant), Qazvin, Rasht, Mashhad, Sanandaj, and Ahvaz (Fig. 1).

The major landfills in Iran’s urban centers vary significantly in terms of capacity, operational history, and environmental control measures. For instance, the Mashhad landfill, established in the 1980s with a capacity of approximately 20 million cubic meters, spans an area of 600 hectares. It has partial leachate collection systems but requires upgrades to fully comply with international standards. Similarly, Tehran’s Kahrizak landfill, one of the oldest and largest, with a capacity of 50 million cubic meters, has undergone several expansions since its inception in the 1970s. Despite improvements such as leachate collection systems and the use of synthetic liners to prevent groundwater contamination, both sites face challenges in fully managing leachate and environmental risks.

In contrast, newer landfills like those in Tabriz and Isfahan have adopted stricter leachate management protocols. The Tabriz site, operational since the early 2000s, processes around 1,200 tons of waste per day and incorporates synthetic liners and leachate collection systems in some areas. However, further sealing is required. Isfahan’s landfill, also established in the 1990s, has a well-developed system for leachate control, employing synthetic liners and regular monitoring to minimize environmental impacts. Other sites, such as Rasht’s Saravan landfill, face significant environmental risks due to inadequate sealing and leachate control, resulting in contamination of local water bodies.

Sampling and physicochemical analysis

Samples were collected during the summer from landfills in the selected Iranian metropolises according to the ISO 5667-10:1992 standard (including any subsequent amendments). To ensure accuracy, reliability, statistical validity, and quality control, three samples were taken from each burial site, resulting in a total of 30 samples prepared for analysis. The samples were transported to the laboratory of the Center for Occupational and Environmental Hazardous Factors at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, where they were kept at 4 °C. Sample kits were distributed to participating landfill sites, and on-site personnel collected grab samples (1 L) in glass bottles, which were preserved with 1 g of sodium azide. These samples were transported to the laboratory overnight in coolers containing ice blocks. Upon arrival, samples were filtered through 0.7 μm glass fibre filters (Whatman, England) and stored at 4 °C until extraction. The physicochemical properties of the leachate samples were analyzed using established methodologies16 and conducted in compliance with ISO standards. pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were measured using a Multimeter AZ-86,505. Biochemical oxygen demand over five days (BOD5) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) were determined using the standard methods recommended by the American Public Health Association (APHA), specifically methods 5210B and 5220 C. Heavy metals, including cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), and arsenic (As), were analyzed after digestion using EPA method 3050B, followed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Agilent 7900). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and phthalate esters were quantified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Agilent 7890 A), adhering to EPA method 8270D. Finally, humic acids were measured using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (PerkinElmer Lambda 35), based on the methodology outlined in ISO 5073.

Selection of the appropriate method to clean samples

The extraction and preparation of real leachate samples were evaluated using solid-phase extraction and clean-up methods, as detailed below. The column used for solid-phase extraction was 3 ml of CHROMABOND® C18 ec, which was acquired from MACHEREY-NAGEL in Germany. At this stage, the percentage of cartridge recovery was also determined (Koplan, 2001). Before extraction, the leachate samples were centrifuged to ensure uniformity and then passed through a Whatman 0.45 μm filter.

The extraction of the samples proceeded as follows: First, the cartridge was washed twice with 2 ml of methanol. Subsequently, the extraction column was washed with distilled water. Next, a specific amount of the sample was passed through the filter. Next, the washing process was carried out using HPLC-grade distilled water. To complete the drying process, the filter was vacuum-packed for 5 min. Finally, ethyl acetate was used to wash the column. For analysis, 50 µl were extracted from the remaining sample under the extraction column and injected into the relevant device.

The analysis of organic compounds and organometallic compounds was performed using HPLC and GC coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) and a flame ionization detector (FID), according to the methods of Ballesteros et al. (2000).

Statistical analysis

After obtaining the data, the relationships between the physical and chemical properties were analysed. Using SPSS software version 16, the basic statistical information (mean, highest, lowest, and standard deviation) of each variable was determined, as well as the Pearson correlation matrix between the main variables (EC, TDS, pH, BOD, COD, heavy metals, PAHs, phthalate esters, acidity, and turbidity) at all landfill sites. Additionally, the Pearson correlation was calculated using Microsoft Excel to further assess the linear relationships between the measured parameters. The (CORREL) function was used to generate the correlation matrix, providing insights into the strength and direction of these relationships, ranging from − 1 to + 1.

Leachate pollution index

The potential environmental impact of the leachate was measured using the leachate pollution index (LPI). This index presents the quantitative potential for leachate pollution, offering a suitable tool for comparison. Using Eq. 1, the LPI can be calculated (Kumar and Alappat, 2005a):

Where LPI = the weighted additive leachate pollution index, wi = the weight for the ith pollutant variable, pi = the subindex value of the ith leachate pollutant variable, n = 18 and Σ wi = 1. However, if data for all pollutants are unavailable, the LPIs can still be calculated using the equation provided, considering only the available pollutant data (Kumar and Alappat, 2005b).

Where

The pollutant parameters for which data are available in this study are m < 18 and Σ wi.

Results and discussion

pH, TDS, and EC

The findings derived from the physicochemical analysis of leachates at the ten sites are succinctly outlined in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. The pH values of the ten examined leachate samples varied between 4.57 and 8.95, with a mean value of 7.143 ± 1.45 observed across all samples. As posited by Kulikowska and Klimiuk (2008), the pH of leachate progressively increases over time, which is attributable to the decreasing concentration of partially ionized free volatile fatty acids. During the methanogenic phase, the proliferation of methane-producing bacteria leads to the overall consumption of intermediate products. In this phase, the transformation of volatile fatty acids into methane and carbon dioxide is closely correlated with the alkalinity of the leachate. The pH of leachate is a fundamental parameter that significantly influences solubility3.

Previous research has demonstrated that low pH levels in leachate may prompt an increase in the presence of calcium, iron, and manganese, whereas high pH conditions during the methanogenic phase tend to lower the concentration of these elements (Ehrig and Stegmann, 2018). The pH values observed in the ten landfills were consistent for leachate discharge, in compliance with environmental standards and regulations17 (Table 1).

Previous research has demonstrated that low pH levels in leachate may prompt an increase in the presence of calcium, iron, and manganese, whereas high pH conditions during the methanogenic phase tend to lower the concentration of these elements18. The pH values observed in the ten landfills were consistent for leachate discharge, in compliance with environmental standards and regulations17. There are no established limits for the leachate discharged into the environment (water or soil) with regard to the electrical conductivity (EC) parameter. The regulations governing effluents from nonhazardous waste landfills have not specified the limit values for this parameter. In this research, the EC values for the 10 leachate samples differed, with sample code 10 having the highest value of 133 ± 30 µS/cm, while the lowest value of 14 ± 1.5 µS/cm was recorded for the sample code 1 leachate sample. The EC values obtained in this study align closely with those reported by Podlasek et al., who reported landfill leachate EC values ranging from 1.5 to 25 mS/cm5. Guérin et al. (2004) reported a broader spectrum of EC, ranging from 9 to 50 mS/cm19. In Germany, the leachate from MSW landfills had a maximum EC level of 425 mS/cm and a median level of 10.9 mS/cm at all sites18. Elevated electrical conductivity levels in leachate could indicate a gradual process of mineralization20. Additionally, it may also signify the presence of sodium and potassium cations21,22.

In the monitoring of leachate, EC is frequently combined with total dissolved solids (TDS). These two parameters are influenced by the amount of dissolved organic and inorganic compounds and serve as indicators of leachate salinity17. The values of these two parameters are directly related to each other3. Elevated levels of dissolved solids can significantly impede water transparency. This limitation in light penetration disrupts photosynthetic processes, ultimately leading to a decrease in primary production and a corresponding increase in water temperature. These alterations in the aquatic environment can have detrimental effects on the growth and development of biological components, particularly those that rely on photosynthesis, such as bacteria and algae. Furthermore, high concentrations of dissolved solids can hinder the growth of many aquatic organisms3.

BOD5, COD, and BOD/COD

The observed mean values for BOD and COD were 9875 mg/l and 44,700 mg/l, respectively, with standard deviations of 7324 mg/l and 27094.47 mg/l, respectively. The highest and lowest recorded BOD and COD values were 21,000 mg/l and 90,000 mg/l and 350 mg/l and 2000 mg/l, respectively. The BOD and COD values obtained correlate with the reported ranges for acetogenic leachate from young landfills, which typically fall between 4000 and 40,000 mg/l for BOD and between 6,000 and 60,000 mg/l for COD3. The BOD, COD, and BOD: COD ratio in leachate serve as measures of microbial processes and the presence of organic pollutants in leachate. The BOD: COD ratio is considered a reliable indicator of landfill conditions, as well as the age of the waste3.

The mean BOD/COD ratio is 0.2077. The highest and lowest recorded BOD/COD ratios were 0.5 and 0.097, respectively. By employing the BOD5/COD ratio, one can delineate the anaerobic phase of waste breakdown. Specifically, a BOD5/COD > 0.4 signifies the acetic phase, while a BOD5/COD ratio below 0.1 is indicative of mature leachate in the methanogenic phase23. Furthermore, a BOD5/COD ratio below 0.1 is regarded as evidence of stable conditions due to the substantial presence of biologically inert substances6. This ratio was less than 0.1 for one of the samples.

When the BOD/COD ratio ranges between 0.1 and 0.4, a transitional phase emerges, and the results obtained by the present research mirror this occurrence18. Figure 3 shows the BOD, COD, and BOD: COD ratios for the 10 measured locations.

Humic acid and phthalates

The highest levels of humic acid (HA) were detected in landfill no. 1, reaching 2200 mg/L, and in landfill no. 2, measuring 1674.4 mg/L. The lowest concentrations of HA were found in landfill no. 5 (135 mg/L). HA represents a significant portion of humic matter, constituting approximately 90% of natural organic material24. Table 2 displays the PAE concentrations at the landfill leachate sites.

Among the PAEs analysed, DEHP was the most common, often at concentrations significantly higher than those of other PAEs. Landfill number 4 registered the highest DEHP concentration at 150 mg/L, followed by landfill number 5 with a concentration of 44.5 mg/L. Similar findings have been documented by other researchers25. These results align with expectations, given that, historically, DEHP has been the most commonly utilized plasticizer, accounting for approximately half of Iran’s total PAE consumption26. DEHP concentrations generally correlate with landfill size. This relationship can be understood by considering that larger landfill sites release greater amounts of waste and plasticizers into leachate, likely due to higher levels of precipitation compared to smaller landfill sites17.

The majority of DEHP concentration results fall within the range of those obtained in studies from Finland (1–89 µg/L) China (n.d.-46 µg/L), Japan (9.6–49 µg/L) and Sweden (< 1–9 µg/L)4,27,28. The concentrations of DEHP measured in this study surpassed those recorded in Germany (up to 240 µg/L), Sweden (97–346 µg/L), and Italy (88–460 µg/L)23.This could be attributed to variations in waste composition, particularly in terms of the quantity and types of plasticizers historically employed in Iran. Another factor could be the timing of the studies; all of them were conducted several years ago, during a period when the use of DEHP was more prevalent than it is today. A separate investigation by Asakura et al. (2004) assessed DEHP levels at two municipal landfill sites in Japan, reporting concentrations of 25 µg/L and 19 µg/L29.

The study revealed that even after remediation in 1996 and ceasing operations in 2011, landfill number 1 continued to contain a substantial concentration of DEHP in its leachate. This phenomenon may be explained by the anticipated sluggish mineralization of DEHP under anaerobic conditions commonly found within landfills30. Due to its lipophilic nature and log Kow of approximately 7.5, DEHP is anticipated to readily adsorb to organic matter, as well as soil or rock substrates, which are typically found in municipal landfills30. DEHP is expected to be persistently released from waste over an extended period31. Our findings confirm these observations: DEHP emissions continue to accumulate many years after landfill closure.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

The levels of PAHs in each sample were comparatively minimal. The highest concentration of total PAHs was detected in landfill no. 2 (26.9 ppb), and the lowest concentration of total PAHs was detected in landfill nos. 8 and 9 (below the limit of quantification, LOQ). Naphthalene was detected in nearly all the samples, likely because of its high volatility and solubility in the leachate32. Among the 16 hydrocarbons analysed, naphthalene had the highest frequency and was present in all the samples. The high amount of naphthalene can be attributed to the presence of industrial waste.

The analysis of the aforementioned results in comparison with data from other countries revealed noteworthy distinctions. Based on the prescribed threshold for PAHs in wastewater intended for discharge into treatment facilities, set below 200 ppb5, our analysis revealed unimpeded compliance across all samples with regard to conveyance into the collection network for treatment. In the investigation conducted by Tan and et al. (2020), the concentration range of PAHs observed in landfill leachate fell within the range of 1.4 to 22 ppb33. In an analogous investigation, the quantified levels of PAHs within landfill leachate exhibited low concentrations ranging from 21 to 0.09 ppb5.

The presence of PAHs in landfill leachate may be attributed to incomplete pyrolysis or combustion processes of organic or solid waste within the landfill environment (Van Caneghem & Vandecasteele, 2014). Elevated levels of PAHs within leachate can induce significant environmental harm due to their extended persistence and inherent toxicity in environmental matrices5.

Heavy metal (HM)

Heavy metals were observed in all the samples. Table 3 details the concentrations of heavy metals found in landfill leachate from the sites studied. The mean Chromium (Cr) level at all locations was relatively low (below 1 mg/L) and fell within the ranges reported in the literature1,8. Similarly, the average concentrations of lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), mercury (Hg), and nickel (Ni) were also low (less than 1 mg/L). This could be due to the alkalinity of the leachate, which likely reduces the solubility of metals, thereby immobilizing them14.

The average Cu concentration in the leachate from these landfills was approximately 420 µg/L, which exceeds the environmental release threshold reported in the literature of 200 µg/L34. This suggests the possible presence of items such as incandescent bulbs, batteries, motor oil, paints, or pharmaceuticals in landfill waste that are not properly segregated34.

The concentrations of heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, Hg, Ni, and Cu in leachate samples were lower than those at landfill sites in India, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia, Germany and China35,36,37,38. Heavy metals are regulated pollutants in wastewater discharged into water or soil8. During the research period, the average concentrations of Hg, Ni, and Cd were below the permissible limits (0.5 mg/L). However, some landfill samples contained leachate with excessive amounts of Cu (over 500 µg/L) and Cr (over 100 µg/L). Consequently, untreated leachate with such high levels of Cu and Cr should not be released into the environment. Additionally, discharging this leachate to municipal wastewater treatment plants can be problematic, as the presence of substances that are particularly harmful to the aquatic environment, such as Cr and Cu, necessitates obtaining a water permit in accordance with regulations39.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed for 16 measured parameters, and the minimum, maximum, mean, median, and standard deviation of each parameter were calculated using SPSS software, as shown in Table 3. The statistical analysis of landfill leachate revealed significant variability across both organic and inorganic parameters. Parameters such as pH, Pb, and Cd displayed low variability, suggesting relatively consistent conditions or sources within the landfill. Conversely, high variability in turbidity, BOD5, COD, and heavy metals (Cr and Cu) indicated heterogeneous waste composition and decomposition processes. This observed variability underscores the inherent complexity of landfill leachate, highlighting the need for comprehensive monitoring and management strategies to mitigate environmental impacts. Regular and detailed leachate analysis, as evidenced by the high standard deviations in several parameters, is crucial for ensuring effective landfill management and environmental protection.

Additionally, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to further explore the relationships between the various measured parameters. Using both SPSS and Microsoft Excel, the correlation matrix between key parameters such as pH, EC, TDS, BOD, COD, heavy metals (Cr, Ni, Pb, Hg, Cu), and organic compounds (PAHs, phthalates, humic acid) was generated. This analysis provided deeper insights into the strength and direction of linear relationships between the variables, helping to identify key interactions and potential areas for targeted interventions in leachate management. The Pearson correlation results are summarized in Table 4.

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between several key parameters. A strong positive correlation was observed between EC and TDS (0.99), as well as between BOD and COD (0.71), indicating that these pairs of parameters are closely related. Moreover, the correlation between certain heavy metals such as Nickel and Mercury (0.91) and Nickel and Copper (0.87) suggests that these metals tend to co-occur in the leachate, potentially originating from similar sources or processes. In contrast, Lead showed weaker correlations with other variables, indicating a more isolated behavior. The correlation between pH and BOD (-0.66) highlights the influence of acidity on organic degradation processes. These findings emphasize the importance of monitoring multiple interacting parameters to better manage leachate treatment and reduce environmental risks. The results of our study are consistent with those of Naveen and et al.3.

Leachate pollution index

The LPI is an effective means of gauging the contamination risk associated with various landfill sites at specific times6. The LPIs were computed using the available data, even though not all parameters incorporated in the LPIs were accessible. It is important to emphasize that every characteristic of the leachate properties notably influences the computations of the LPIs6.

The attributes of MSW leachate analysed in this study, in conjunction with the parameters employed for computing the LPIs, such as the pollutant weight factor (wi) and subindex value (pi), are outlined in Table 2. This research utilized LPIs to evaluate the pollution potential of leachate on a theoretical scale ranging from 5 to 100 40. The samples from Ahvaz had the highest LPI value, approximately 27.5, while the samples from Tehran, post treatment, exhibited the lowest value at 13.2. The elevated LPIs can be attributed to high concentrations of COD, BOD, and specific metal elements such as Cr, As and Fe1. The geographical location of Ahvaz, characterized by its humid climate, undoubtedly exerts a notable influence in this context23.

According to Somani et al. (2019), environmental degradation is less likely to occur if the LPI remains below the threshold of 3541. Based on the data depicted in Fig. 5, the LPIs obtained from all the samples remain below the critical threshold of 35, suggesting that there is currently no imminent environmental threat. Nevertheless, according to Maiti et al. (2016), who stated that an LPI exceeding the standard threshold of 7.38 is highly hazardous and illegal for discharge into surface water, all the samples in this study surpassed this critical value42. This indicates a significant need for more stringent regulatory measures and remediation efforts. Additionally, leachate treatment exerts a substantial effect on mitigating leachate pollution23. Figure 5 displays the calculated Landfill Pollution Index (LPI) for 10 landfills sampled from Iranian metropolises.

Additionally, 60% of the samples exhibited a higher LPI than that observed in Malaysia and Portugal6,23. High LPIs from landfills, numerically greater than 7.5, indicate inappropriate environmental conditions and indicate an urgent need for attention23.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the substantial variability in the physicochemical properties and pollution potential of leachate from major municipal solid waste landfills in Iranian cities. The results indicated that older landfills, such as the one in Ahvaz, exhibited higher contamination levels compared to newer or more controlled sites, such as those in Tehran after treatment. This discrepancy is likely due to differences in operational practices and waste management efficiency. Climatic conditions in different regions, including both semiarid and humid climates, also influenced the degradation rates of waste and, consequently, the leachate composition. Notably, landfills in wetter regions, like Rasht, displayed distinct leachate characteristics, including higher levels of organic matter degradation.

The findings revealed a wide range of contaminants, including significant levels of BOD₅, COD, TDS, heavy metals, phthalates, and humic acids. Despite the relatively low concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and mercury, the presence of hazardous organic compounds, such as phthalates and PAHs, poses a serious environmental threat, particularly to groundwater quality. The primary contribution of this study lies in its comprehensive evaluation of leachate characteristics across multiple cities using the Leachate Pollution Index (LPI), offering critical insights for policymakers and environmental managers to improve waste management strategies and mitigate the environmental impact of landfill leachates. Greater emphasis on adopting effective leachate treatment systems and reinforcing regulatory frameworks is necessary to safeguard public health and natural resources.

Data availability

All of the data analyzed and used during the current study will be available from the corresponding author onreasonable request.

References

Saha, P., Saikia, K. K., Kumar, M. & Handique, S. Assessment of health risk and pollution load for heavy and toxic metal contamination from leachate in soil and groundwater in the vicinity of dumping site in Mid-brahmaputra Valley, India. Total Environ. Res. Themes. 8, 100076 (2023).

Arunbabu, V., Indu, K. & Ramasamy, E. Leachate pollution index as an effective tool in determining the phytotoxicity of municipal solid waste leachate. Waste Manag. 68, 329–336 (2017).

Naveen, B., Mahapatra, D. M., Sitharam, T., Sivapullaiah, P. & Ramachandra, T. Physico-chemical and biological characterization of urban municipal landfill leachate. Environ. Pollut. 220, 1–12 (2017).

Wowkonowicz, P. & Kijeńska, M. Phthalate release in leachate from municipal landfills of central Poland. PLoS One. 12, e0174986 (2017).

Podlasek, A., Vaverková, M. D., Koda, E., Jakimiuk, A. & Barroso, P. M. Characteristics and pollution potential of leachate from municipal solid waste landfills: Practical examples from Poland and the Czech Republic and a comprehensive evaluation in a global context. J. Environ. Manage. 332, 117328 (2023).

Hussein, M., Yoneda, K., Zaki, Z. M. & Amir, A. Leachate characterizations and pollution indices of active and closed unlined landfills in Malaysia. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. 12, 100232 (2019).

Abunama, T., Moodley, T., Abualqumboz, M., Kumari, S. & Bux, F. Variability of leachate quality and polluting potentials in light of leachate pollution index (LPI)–a global perspective. Chemosphere. 282, 131119 (2021).

Abu-Daabes, M., Qdais, H. A. & Alsyouri, H. Assessment of heavy metals and organics in municipal solid waste leachates from landfills with different ages in Jordan. (2013).

Pasalari, H., Farzadkia, M., Gholami, M. & Emamjomeh, M. M. Management of landfill leachate in Iran: Valorization, characteristics, and environmental approaches. Environ. Chem. Lett. 17, 335–348 (2019).

Ansari, F. A. et al. Evaluation of various solvent systems for lipid extraction from wet microalgal biomass and its effects on primary metabolites of lipid-extracted biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 15299–15307 (2017).

Vahabian, M., Hassanzadeh, Y. & Marofi, S. Assessment of landfill leachate in semi-arid climate and its impact on the groundwater quality case study: Hamedan, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 1–19 (2019).

Adhikari, B., Parajuli, A., Manandhar, D. R. & Khanal, S. N. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 012022 (IOP Publishing).

de Domingos, M. F. Effect of the association of coagulation/flocculation, hydrodynamic cavitation, ozonation and activated carbon in landfill leachate treatment system. Sci. Rep. 13, 9502 (2023).

Mor, S., Negi, P. & Khaiwal, R. Assessment of groundwater pollution by landfills in India using leachate pollution index and estimation of error. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. 10, 467–476 (2018).

Lothe, A. G. & Sinha, A. Development of model for prediction of Leachate Pollution Index (LPI) in absence of leachate parameters. Waste Manage. 63, 327–336 (2017).

Olivero-Verbel, J. & Padilla-Bottet, C. De La Rosa, O. Relationships between physicochemical parameters and the toxicity of leachates from a municipal solid waste landfill. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 70, 294–299 (2008).

Wdowczyk, A. & Szymańska-Pulikowska, A. Analysis of the possibility of conducting a comprehensive assessment of landfill leachate contamination using physicochemical indicators and toxicity test. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 221, 112434 (2021).

Cossu, R., Ehrig, H. & Muntoni, A. Physical–Chemical leachate treatment. Solid Waste Landfilling. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam.. https://doi.org/10 1016, 00028 – 00020 (2018).

Guérin, R. et al. Leachate recirculation: moisture content assessment by means of a geophysical technique. Waste Manage. 24, 785–794 (2004).

Brahmi, S. et al. Assessment of groundwater and soil pollution by leachate using electrical resistivity and induced polarization imaging survey, case of Tebessa municipal landfill, NE Algeria. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1–13 (2021).

Yeilagi, S., Rezapour, S. & Asadzadeh, F. Degradation of soil quality by the waste leachate in a Mediterranean semi-arid ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 11, 11390 (2021).

Gupta, A. & Rajamani, P. Toxicity assessment of municipal solid waste landfill leachate collected in different seasons from Okhala landfill site of Delhi. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng. 8, 357–369 (2015).

Wijekoon, P. et al. Progress and prospects in mitigation of landfill leachate pollution: risk, pollution potential, treatment and challenges. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, 126627 (2022).

Bazrafshan, E., Biglari, H. & Mahvi, A. H. Humic acid removal from aqueous environments by electrocoagulation process using iron electrodes. J. Chem. 9, 2453–2461 (2012).

Hou, C., Lu, G., Zhao, L., Yin, P. & Zhu, L. Estrogenicity assessment of membrane concentrates from landfill leachate treated by the UV-Fenton process using a human breast carcinoma cell line. Chemosphere. 180, 192–200 (2017).

Darvishmotevalli, M. et al. Association between prenatal phthalate exposure and anthropometric measures of newborns in a sample of Iranian population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 50696–50706 (2021).

Qi, C. et al. Contaminants of emerging concern in landfill leachate in China: A review. Emerg. Contaminants. 4, 1–10 (2018).

Wijesekara, S. et al. Fate and transport of pollutants through a municipal solid waste landfill leachate in Sri Lanka. Environ. Earth Sci. 72, 1707–1719 (2014).

Asakura, H., Matsuto, T. & Tanaka, N. Behavior of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in leachate from MSW landfill sites in Japan. Waste Manage. 24, 613–622 (2004).

Eslami, A. et al. Synthesis of modified ZnO nanorods and investigation of its application for removal of phthalate from landfill leachate: A case study in Aradkouh landfill site. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 19, 133–142 (2021).

Tran, H. T. et al. Biodegradation of high di-(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) concentration by food waste composting and its toxicity assessment using seed germination test. Environ. Pollut. 316, 120640 (2023).

Kotowska, U., Kapelewska, J. & Sawczuk, R. Occurrence, removal, and environmental risk of phthalates in wastewaters, landfill leachates, and groundwater in Poland. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115643 (2020).

Jian, T. P., Ul Mustafa, B., Isa, M. R. H., Yaqub, M., Ho, Y. C. & A. & Study of the water quality index and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon for a river receiving treated landfill leachate. Water. 12, 2877 (2020).

Zainol, N. A., Aziz, H. A. & Yusoff, M. S. Characterization of Leachate from Kuala Sepetang and Kulim landfills: A comparative study. Energy Environ. Res. 2, 45 (2012).

Rajoo, K. S., Karam, D. S., Ismail, A. & Arifin, A. Evaluating the leachate contamination impact of landfills and open dumpsites from developing countries using the proposed Leachate Pollution Index for developing countries (LPIDC). Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. 14, 100372 (2020).

Gunarathne, V. et al. Environmental pitfalls and associated human health risks and ecological impacts from landfill leachate contaminants: Current evidence, recommended interventions and future directions. Sci. Total Environ., 169026 (2023).

Bove, D. et al. A critical review of biological processes and technologies for landfill leachate treatment. Chem. Eng. Technol. 38, 2115–2126 (2015).

Yan, H., Cousins, I. T., Zhang, C. & Zhou, Q. Perfluoroalkyl acids in municipal landfill leachates from China: Occurrence, fate during leachate treatment and potential impact on groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 524, 23–31 (2015).

Mavakala, B. K. et al. Leachates draining from controlled municipal solid waste landfill: Detailed geochemical characterization and toxicity tests. Waste Manage. 55, 238–248 (2016).

Kumar, D. & Alappat, B. J. Analysis of leachate pollution index and formulation of sub-leachate pollution indices. Waste Manag. Res. 23, 230–239 (2005).

Somani, M., Datta, M., Gupta, S., Sreekrishnan, T. & Ramana, G. Comprehensive assessment of the leachate quality and its pollution potential from six municipal waste dumpsites of India. Bioresource Technol. Rep. 6, 198–206 (2019).

De, S., Maiti, S., Hazra, T., Debsarkar, A. & Dutta, A. Leachate characterization and identification of dominant pollutants using leachate pollution index for an uncontrolled landfill site. Global J. Environ. Sci. Manage. 2, 177–186 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Research Center for Occupational and Environmental Hazard Factors at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, for providing financial assistance and collaborating on this study. This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, with ethical approval code [IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1395.115].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hojjat Nadimi: Responsible author; contributed to writing a part of the text of the article and performed the final revision.Mohammad Hossien Saghi: Author of the main text; involved in data collection and data analysis.Akbar Eslami: Conducted data analysis; prepared and analyzed samples; collected information on the working method.Seyed Nadali Alavi Bakhtiarvand: Conducted data analysis; prepared and analyzed samples; collected information on the working method.Ali Oghazeyan: Performed statistical analysis and calculations; prepared tables and charts.Somayeh Setoudeh: Involved in text writing and data collection; analyzed samples.Mohammad Sadegh Sargolzaei: Responsible for the revision and correction of grammar and spelling.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saghi, M.H., Nadimi, H., Eslami, A. et al. Characteristics and pollution indices of leachates from municipal solid waste landfills in Iranian metropolises and their implications for MSW management. Sci Rep 14, 27285 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78630-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78630-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Numerical modelling of fate and transport of heavy metal contaminant in an open dumping yard, South India

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2026)

-

Integrated Electrocoagulation and Adsorption Strategy for the Treatment of Fresh Landfill Leachate

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)