Abstract

Recent advancements in hyperspectral imaging (HSI) for early disease detection have shown promising results, yet there is a lack of validated high-resolution (spatial and spectral) HSI data representing the responses of plants at different stages of leaf disease progression. To address these gaps, we used bacterial leaf spot (Xanthomonas perforans) of tomato as a model system. Hyperspectral images of tomato leaves, validated against in planta pathogen populations for seven consecutive days, were analyzed to reveal differences between infected and healthy leaves. Machine learning models were trained using leaf-level full spectra data, leaf-level Vegetation index (VI) data, and pixel-level full spectra data at four disease progression stages. The results suggest that HSI can detect disease on tomato leaves at pre-symptomatic stages and differentiate bacterial disease spots from abiotic leaf spots. Using VI data as features for machine learning improved overall classification performance by 26–37% compared to the direct use of raw data. Critical wavelength bands and VIs varied across disease progression stages, suggesting that pre-symptomatic disease detection relied more on changes in leaf water content (1400 nm) and plant defense hormone‐mediated responses (750 nm) rather than changes in leaf pigments or internal structure (800–900 nm), which may become more crucial during symptomatic stages. In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of bacterial spot disease, revealing the potential benefits of leaf structure segmentation and VI group pattern analysis in HSI studies for the early detection of leaf diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant pathogens can spread through shipments of stock plants between production facilities, and from production facilities to growers, retailers, and consumers1,2,3. Failing to prevent the introduction and spread of plant diseases can cause up to 40% yield loss in agricultural production4. A central challenge in preventing accidental pathogen dissemination and disease outbreaks is the difficulty in detecting many plant diseases at their early stages5. As a result, asymptomatic plants can spread undetected pathogens when being shipped from one location to another. Due to these challenges, early disease detection, as a sub-domain in precision agriculture, has become a key focus in plant disease surveillance.

Traditionally, disease detection and diagnosis rely on methods such as microscopic observation, culturing, immunological assays, and molecular tests6,7. However, many of these methods have limited sensitivity or specificity, and hence such conventional methods are not efficient in tackling emerging crop diseases. There is a pressing need for new tools that offer rapid, sensitive, and cost-efficient plant disease detection and diagnosis. With recent advancements in biological engineering and computer sciences, various new disease-detection tools have been proposed and developed. Among them, biological sensing and imaging-based remote sensing techniques appear to be the most promising8,9,10,11,12.

Imaging-based tools can provide high-throughput and non-invasive disease detection, facilitating the automation of crop disease detection in both field and controlled environments13,14,15,16. Major imaging-based disease detection approaches include hyperspectral imaging (HSI), multispectral imaging (MSI), RGB imaging, thermal imaging, and fluorescence imaging. Hyperspectral and multispectral imaging appear to be promising solutions for crop disease detection at various scales, as they are capable of performing spaceborne, aerial, and close-range (proximal) imaging tasks using satellites, airplanes, unmanned aerial vehicles, ground vehicles, and lab devices17.

HSI and MSI have been successfully applied for early disease detection, i.e., detecting plant diseases before any symptoms become visible (to human eyes) on the infected plants18,19,20,21. In these studies, early detection was achieved through recording and analyzing the spatial and spectral patterns of plant pixels at different wavelength bands. For example, in-field detection of Alternaria solani in potato, Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum in carrot, grapevine vein-clearing virus in grapevines, and multiple pathogens in winter wheat have been achieved using HSI or MSI12,22,23,24. The accuracy in those studies ranged from 60 to 93%. Studies conducted in controlled environments also showed promising results. A previous study showed that five different foliar diseases of wheat can be detected by using HSI under greenhouse conditions, with an average accuracy over 90%8. Similarly, HSI was used to achieve the detection of Phytophthora infestans and Alternaria solani on potato, as well as the detection of Sclerotium rolfsii on peanut, with an accuracy higher than 80%18,19,25. Previous studies revealed multiple bands in VIS (around 500 nm, 550 nm, and 690 nm), Far-red (around 750 nm), and SWIR (around 1890 nm, 2300 nm, and 2380 nm) regions that are informative to differentiate between healthy and diseased crops12,18,19,22,23,24,26.

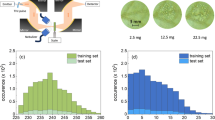

Although the studies mentioned above revealed the potential of applying spectral imaging to crop disease detection, especially at early stages, there are some research gaps we seek to fill with this study. First, in this study, we used bacterial leaf spot (BLS) of tomato caused by Xanthomonas perforans as a model system to characterize changes in leaf reflectance from before inoculation through disease onset to the advanced stage of disease progression (Fig. 1). Tomato has been widely used as a model system in HSI-based early disease detection of fungal, viral, and bacterial leaf diseases27,28,29,30,31. However, there is a lack of HSI data on disease progress specific to tomato BLS or information on differentiating abiotic spots from bacterial spots. Second, several studies utilized sensors that only collect data from a small spatial area8,18,19,25. In our research, we used hyperspectral camera which provides higher spatial resolution than these existing studies. Third, some studies used multi-spectral cameras that collect data from a few wavelength bands20,22. In this work, we used cameras with higher spectral resolution. Fourth, in a few studies that focused on pre-symptomatic detection, the absence of pathogen population in asymptomatic plant samples was not validated24,25, or was not confirmed for every sample used for imaging32. In our study, we performed detailed quantification of pathogen load for inoculated plants such that we can determine correlation between pathogen load and spectral data. Finally, there is a lack of information on environmental/plant or abiotic factors that might influence plant reflectance and confound disease detection. In our study, we tested multiple background materials to understand the effect of how imaging background impacts the spectral analysis. Our hypothesis was that HSI combined with machine learning would be capable of early detection of BLS on tomato seedlings, which could be useful in monitoring tomato transplants grown in greenhouses so that infected seedlings can be removed to prevent outbreaks in tomato production fields.

Results

Disease progression and bacterial growth

All tomato plants inoculated with X. perforans showed initial symptoms on day 4 (4 dai, Fig. 2). The initial disease incidence was approximately 18%, and the disease severity index was 7%. Disease continued to progress from 4 to 7 dai, with leaf spots becoming bigger and darker while leaves wilted and decayed. The culture results showed that X. perforans was absent before inoculation in both inoculated and uninoculated groups. X. perforans reached 105 CFU/cm2 leaf area in inoculated plants, 2 h after inoculation (Fig. 2). Bacterial populations continued to grow from 0 to 3 dai, even though no visible leaf symptoms were observed. The growth curve indicated that bacterial growth was exponential throughout the experiments and the bacterial population peaked 6 to 7 dai at 108 CFU/cm2 leaf area. All uninoculated plants remained healthy-looking and free of X. perforans, with a few uninoculated plants showing white paper texture spots (abiotic spots) on 15% of leaves.

Scan precision and impacts of background, leaf size, leaf structure on tomato leaf reflectance

LDA results suggested that the reflectance data of the same leaves were similar between scans. Healthy leaf data showed clear separation from diseased leaf data (Fig. 3A). Linear Discriminant 1 (LD1) value was 0.85, indicating major differences between healthy and diseased groups, while LD2 value was 0.09, suggesting close similarity between VISNIR and SWIR data from two scans on the same leaves. There was a clear separation between VISNIR data collected on the white background reference panel (Fig. 3B, green and pink) and data collected on the black background (Fig. 3B, purple and beige). In the SWIR data, the healthy (green and purple) and diseased leaf data (pink and beige) were distinctly separated without being affected by the background. The reflectance data was not affected by leaf size (Fig. 3C, LD2 = 0.00). In contrast, pixels were clearly grouped by different leaf structures based on the reflectance data (Fig. 3D).

Comparison of models trained with leaf-level full spectra data

The testing accuracy and weighted-averaged F1 scores were compared at four stages of disease progression. Model performance varied between disease progression stages and between VISNIR and SWIR wavelength ranges (Table S1). Model performance increased from the pre-symptomatic (beginning and early) to the post-symptomatic (mid and late) stages. Among the seven models tested, the LDA models had the best performance for VISNIR and SWIR data across all four stages (Table S1).

When we performed a binary classification using uninoculated versus inoculated plants, the VISNIR testing accuracy (0.61 ± 0.05) and the F1 score (0.47 ± 0.02) were much higher than models trained to classify four stages. The same trend was observed with the SWIR data across all models (testing accuracy: 0.57 ± 0.10, F1 score: 0.45 ± 0.05). At the early stage, LDA models performed the best for both VISNIR (0.55) and SWIR data (0.64). At mid stage, LDA model performance increased to 0.74. This level of accuracy and F1 score showed that some of the classes were not separable. For example, in Fig. 4A, uninoculated and inoculated leaves were considered as two separate groups, however, both samples included health leaves and the LDA plot showed that these data points could not be separated.

To visualize the classification results, we generated LDA plots (Fig. 4). These plots showed that LDA was able to separate inoculated from uninoculated leaves as early as 2 h after inoculation while no difference was found before inoculation, with either VISNIR or SWIR data. At the early, pre-symptomatic stage (1 dai to 3 dai), VISNIR data revealed a difference between inoculated and uninoculated leaves in LDA, but SWIR data failed to do so (Fig. 4B). At the disease onset stage (4 dai), LDA showed clear separation of data points, (Fig. 4C) for VISNIR data. SWIR data did not show a clear differentiation for 4 dai. Both VISNIR and SWIR showed a difference between inoculated and uninoculated leaves across 5 dai, 6 dai, and 7 dai (Fig. 4D). In all these analyses, the first linear discriminant (LD1) accounts for most of the between-class variance (Fig. 4A–D). However, the cross-validation performance (F1 score and accuracy in Table S1) was not high, which means the model was not able to generalize to the leave-out-testing data.

To understand which wavelengths played important roles, we calculated the gini importance (Table S2). At 0 dai of disease progression, multiple wavelength bands in the red edge/far-red (740–750 nm, and 750–780 nm), near-infrared (1000–1025 nm), and short-wave infrared (around 1400 nm, 1700 nm, 1529 nm, 1380 nm, 1007 nm, etc.) regions were important in differentiating infected from uninoculated tomato leaves (Figure S1A). At the early stage (1–3 dai, pre-symptomatic), wavelength bands in far-red (around 743 nm, 712 nm, and 733 nm) and short-wave infrared (around 1700 nm, 1600 nm, 1400 nm, etc.) were still important, and several bands in the purple-blue regions (around 393 nm, 404 nm, 425 nm, and 478 nm) became important (Figure S1B). At mid stage (4–5 dai, symptomatic), wavelength bands in far-red (around 690 nm and 750 nm) and near-infrared (750–780 nm, around 850 nm, 900–930 nm, around 1000 nm, 1050–1100 nm, etc.) stood out (Figure S1C). At the late stage (6–7 dai), the important bands shifted to the red region (600−630 nm) and short-wave infrared bands around 1400 nm showed higher importance than other wavelengths (Figure S1D).

Comparison of models trained with leaf-level VI data

Instead of using all spectral bands, we tested whether using specific VI can improve machine learning prediction. Using the VIs extracted from the spectral data (collected from 0 to 7 dai), all machine learning models showed good performance across all four stages during disease progression (Table S3). The weighted-averaged F1 scores were the same as the accuracy scores. These results indicate that calculating VIs and using them as features for machine learning significantly improved overall performance in classifying diseases compared to using raw data directly.

VIs (Table S4) that were important in classifying infected tomato leaves varied between disease progression stages (Fig. 5). At the beginning (0 dai and 2 h ai), CTR2 was the most important VI (see discussion). At the early stage (1-3 dai), LLSI, NDWI-hyperion, MSI, PSSR, CTR2, and NDVI were relatively more important than the other VIs. After the onset of visible disease symptoms, NDVI, PRI, and PSSR had higher importance scores than other VIs. At the mid stage, BRI2, CTR2 and SIPI were also important, and mNDVI705 and LLSI had higher importance scores than other VIs at the late stage, in addition to NDVI, PRI, and PSSR.

Comparison of models trained with pixel-level full spectra data

To explore the power of spatial resolution from HSI, we performed pixel-level full spectra classification. Pixels sampled from 7 dai leaf images were classified into nine classes (Fig. 6). Overall, RF models showed better performance than others, with both VISNIR (0.63 ± 0.13) and SWIR (0.57 ± 0.16) data (Fig. 6A). Even though the performance of LDA is not the highest, LDA plots provided interpretable visualizations and showed interesting results (Fig. 6B). First, background pixels were distinctly different from leaf pixels in both VISNIR and SWIR ranges. Second, abiotic spots formed two adjacent clusters, which were far from bacterial spots, green healthy leaf areas, and green areas on symptomatic leaves. Third, bacterial spots formed another two adjacent clusters, which were far from other classes in the VISNIR plot, but close to green healthy leaf edge pixels in the SWIR plot. Finally, pixels from GH and GS were inseparable in the SWIR LDA plot. However, GH-e and GS-e formed two adjacent clusters. GH-iv and GS-iv also formed two adjacent clusters, which were clearly separated from other groups in the VISNIR LDA plot.

Classification model performance (A), class dissimilarity (B), and the confusion matrix generated from the best models (C & D) analyzed with 7dai pixel-level full spectra data. Pixels were classified into nine groups: green areas on the edge of uninoculated healthy leaves (GH-e), green areas in the interveinal areas on uninoculated healthy leaves (GH-iv), bacterial spots on the edge of infected leaves (BS-e), bacterial spots in the interveinal areas on infected leaves (BS-iv), abiotic spots on the edge of uninfected leaves (AS-e), abiotic spots in the interveinal areas on uninfected leaves (AS-iv), green areas on the edge of symptomatic tomato leaves (GS-e), green areas in the interveinal areas on symptomatic tomato leaves (GS-iv), and background (bg) pixels.

The confusion matrix of the best classification models showed that most confusion occurred between the edge and interveinal classes within the same type of leaf samples (Fig. 6C–D). With VISNIR data (Fig. 6C), it was possible to differentiate GH completely from BS-e/iv, AS-e/iv, and GS-iv. BS was 100% differentiated from all other groups except for a 22% mis-classification between AS-e and BS-e. GS were 100% differentiated from GH and BS groups, except for less than 20% mis-classification between GS and AS-iv. With SWIR data (Fig. 6D), GH-iv, BS-e, AS-e, and GS-iv were 100% differentiated from all other leaf types. The classification of GH-iv and BS-iv was not as successful, due to multiple cross-group confusion. The gini importance results from RF models suggested that wavelength bands in 550–600 nm, 690 nm, and 1400–1450 nm were important in classifying the above-mentioned leaf pixels (Figure 7). A strong positive correlation (Table S5) was found between VISNIR and SWIR model (trained with leaf-level full spectra data) accuracy (r = 0.93, P = 0.07), between VISNIR accuracy and bacterial population (r = 0.96, P = 0.04), as well as between SWIR accuracy and bacterial population (r = 0.99, P = 0.01).

Prediction from leaf and living plant images

The prediction results suggested that VISNIR-RF was relatively accurate in detecting BLS on detached diseased leaves, although some pixels on uninoculated green healthy leaves were misclassified as “green areas on symptomatic leaves” (Fig. 8). The classification of abiotic spots was generally accurate (Fig. 8). The prediction of SWIR pixels on detached leaves was less successful as the majority of bacterial spot interveinal pixels were misclassified as abiotic spots (Fig. 8). The whole-plant-image prediction was able to capture the presence of abiotic spots on healthy tomato plants with both VISNIR (Figure S5A) and SWIR models (Figure S5B) and also classified some bacterial spots correctly (Figure S5C-D). However, the incidence of false positives was high as a large number of healthy leaf pixels and a small portion of background pixels were misclassified as bacterial spots (Figure S5A-D).

Discussion

In this study, we utilized leaf/plant-level hyperspectral images and established pathogen population data (ground truth labels) collected from 7 consecutive days to analyze the differences between plants with BLS disease and healthy plants. The results suggested that HSI is capable of detecting BLS on tomato leaves at pre-symptomatic stages and differentiating BLS spots from biotic spots. Through machine learning analysis, we found that wavelength bands and VIs that were important in classification varied among disease progression stages. Interestingly, the change in which wavelength bands were important during the 7-day disease progression was consistent with that of VI patterns, which in turn was highly correlated with the growth of bacterial populations in tomato leaves and aligned with the physiological changes occurring in tomato leaves. For example, the CTR2 index used 695 nm and 760 nm as inputs and is an important VI for the beginning stage of infection. ML ranked them as the 11th (689 nm) and 1st (753 nm) most important bands (Table S2). For LLSI, which is important for early-stage infection, 720 nm, 530 nm, and 830 nm were used. ML ranked 740 nm as 1st, 550 nm as 17th, and 840 nm as 14th, out of 281 possible bands (17/281 = top 6%). For NDVI, 670 nm and 800 nm were used. ML ranked 690 nm and 750 nm as 5th and 1st, respectively. The ML method did not select the exact band (695 nm vs. 689 nm, for example), partly due to the noise in the data and neighboring bands are highly correlated. In the case of NDVI, the hyperspectral reflectance above 750 nm is more ‘flat’ than below 750 nm, which explains why ML does not select 800 nm specifically.

Both VISNIR and SWIR data detected clear differences between the control and inoculated tomato leaves 2 hours after inoculation. Wavelength bands around 740–750 nm and 1404 nm weighed more in differentiating these two groups at this stage. Previous researchers reported that 750 nm (far-red) and nearby bands in far-red and near-infrared regions are associated with disease in various crops including tomato26,33,34. Other research suggested that far-red is associated with tomato defense hormone-mediated responses35, which have a big impact on tomato morphology, development, photosynthetic performance, and fruit production36,37. The other important band, 1400 nm, is known to be associated with water and carbon dioxide absorption38,39. It is known that Xanthomonas pathogens often cause water soaking on tomato leaves by drawing water into the apoplast (the intercellular space in plant tissues) from the leaf surface40,41, and that the water-soaking effect allows other bacteria to enter plants within 30 min. Considering that bacterial populations in tomato leaves already reached 105 CFU/cm2 leaf area at 2 h ai, it is likely that the changes at 1400 nm that we observed at 2 h ai were caused by water-soaking induced by X. perforans.

During the pre-symptomatic stage (1–3dai), VISNIR data continued to support the differentiation between healthy and infected plants with the most important bands around 743 nm. SWIR data were less supportive of such a differentiation, possibly because at this stage the pathogen was already established in the leaf tissues and no longer needed to draw a large amount of water from the leaf surface. Although many bacterial, fungal, and oomycete pathogens induce water-soaking effects and water-soaked spots are often observed as the first visual symptom on infected plants, water-soaking is a transient process induced in the early infection (24 hr ai) and disappears before the late symptomatic stage in some pathosystems42. Our study provided evidence showing that HSI allows us to observe such an effect occurring at the early infection stage, before visual symptoms could be observed. However, further studies are needed to investigate the role of the 1400 nm band in plant responses to non-water-soaking pathogens, insects, and abiotic stresses in more complex environment settings. Exploring the impact of biopesticides and resistant tomato varieties on HSI signatures could also be a valuable area for future research.

Both VISNIR and SWIR data showed distinct differences between inoculated and uninoculated from 5 to 7 dai. Compared to the pre-symptomatic stages, important wavelength bands shifted towards the near-infrared region (750–1200 nm) during the symptom development (mid, 4 -5 dai) stage. Since at this stage X. perforans had already started to damage leaf structures and affected photosynthesis, it is not surprising to see a hyperspectral pattern different from those of the pre-symptomatic stages. At the mid stage, multiple bands from 755 to 1200 nm had big impacts on the classification. Previous studies showed that reflectance data at those bands are correlated with tomato defense hormone-mediated responses35, leaf pigment contents16,43 and leaf structures44,45.

VI pattern changes across BLS disease progression stages were consistent with the hyperspectral band pattern changes we observed with full spectra analysis. Previous publications reported that the importance of individual VIs changed as plant disease progressed30 (Pane et al. 202132). In this study, in addition to identifying the most informative individual VIs, we treated the entire selection of VIs as a supergroup and observed its pattern at different stages during disease progression. The VIs we selected can be categorized into four groups focusing on leaf pigment and photosynthesis, stress response, leaf structure, and leaf water content. This way, we were able to compare the physiological changes of inoculated leaves and the change of VI patterns. This study provided evidence supporting our hypothesis that pre-symptomatic BLS detection relies more on tomato leaf water content and disease hormone-mediated plant response monitoring rather than leaf pigment or leaf structure observations. As the disease progresses to more advanced stages, the importance of leaf pigment and structure monitoring increases. Therefore, we suggest that future studies could include various groups of VIs. Based on the dynamic change of VI patterns during disease progression observed in this study, we hypothesize that VI patterns can be engineered with time series data to create new features that might be more informative in disease detection.

We also investigated the influence of potential confounding factors including scan precision, background materials, leaf size, and leaf structure. The results showed background materials and leaf structure have high impacts on the reflectance data. When light interacts with leaves, some of it is transmitted through the leaf tissue. This transmitted light can be affected by the properties of the background material. If the background has high reflectance, it can reflect transmitted light back through the leaf, thereby altering the observed HSI signature. In Blanch-Perez-del-Notario et al.46 study, the authors applied HSI to classify different textiles (wool, 100% cotton, 80% cotton blend, 60% cotton blend, etc.) and found that the impact of the color on the textile spectra is very high in the VNIR range, with black color giving them highly consistent results (~ 100% accuracy). Their results showed that black cotton fabric has a distinct HSI signature that is less variable, which makes it a good background choice. However, black cloth has a high reflectance in the NIR region, which could lead to segmentation challenges. By analyzing the confusion matrices of all the classification models, we found edge pixels tended to cause more cross-group confusion than pixels from other tissues. This is likely due to the fact that edge tissues are thinner than other tissues, and the reflected light from the cotton background can penetrate back through this thin tissue. In this case, black moosgummi could be a cost-effective alternative.

In this study, the prediction results obtained from detached leaf images were relatively accurate, where abiotic spots, bacterial spots, and most healthy leaves were classified correctly. However, this study was conducted using a limited number of samples. Moreover, whole-plant-image classification had relatively poor performance. Applying our models on living-plant images was difficult, as our training data were acquired from detached leaves laying on a flat surface. Different leaves on living plants have different leaf angles and distances to the camera, which can heavily reduce the accuracy of our classification models. To tackle this problem, a large amount of validated disease-related HSI data with depth information are needed, and deep learning approaches could also be considered47,48.

In conclusion, the results from this study demonstrate the possibility of using HSI and machine learning to detect BLS at pre-symptomatic stages. Using leaf-level and pixel-level data, with full spectra and VI analyses, we matched the physiological leaf changes and pathogen growth during disease progression with the HSI patterns we observed. Our findings about the significance of VI group patterns and leaf structure segmentation can help design more effective data collection and analysis methods. Overall, the outcome may benefit future HSI-related crop disease research studies and applications. One example of such applications is to scan tomato seedlings in transplant production facilities to identify those asymptomatic, infected plants which could potentially reduce disease spreading from seedlings to the field.

Methods

Plant and inoculum preparation

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seeds (c.v. Early Girl, Mountain Valley See Co.) were seeded in a 48-cell tray and grown under greenhouse conditions between 25 and 38 °C for three weeks. The tomato seedlings germinated seven to ten days after seeding and they were fertilized (Osmocote Smart-Release, ICL) one time two weeks after seeding. Plants were irrigated for two minutes twice a day at eight o’clock in the morning and five o’clock in the afternoon. Three-week-old tomato plants were used for the inoculation experiments. The plants were sprayed with sterilized water and bagged for 24 hours before inoculation and another 24 h after inoculation.

Inoculum preparation

A Xanthomonas perforans strain isolated previously from a tomato field in Virginia was grown in a shaker incubator overnight in R2 broth (Teknova) at 28 °C and 200 rpm. Two-hundred-micro-liter aliquots of X. perforans. liquid cultures were spread on R2A medium amended with 20 mg/L of the antibiotic rifampicin (Sigma-Aldrich). The survivors grown on 20 mg/L rifampicin-R2A medium were transferred to 50 mg/L rifampicin-R2 agar medium, and this process was repeated on 100, 150, and 200 mg/L rifampicin-R2 agar medium. The survivors grown on 200 mg/L rifampicin-R2A medium were cultured on 200 mg/L rifampicin-R2A agar medium again to confirm their resistance to rifampicin. Six final survivors were selected for pathogenicity tests on three-week-old healthy tomato plants, and the one that showed the highest virulence was used for the inoculation experiments. The inoculum consisted in bacteria resuspended in 10 mM MgSO4 at a concentration of 1–5 × 107 CFU/ml.

Inoculation and experimental design

Tomato plants were inoculated by dipping the plants (including stems and leaves) into a sterilized plastic cup filled with 300 ml X. perforans inoculum mixed with 0.02% Silwet, for a minute. The control plants were dipped in a sterilized plastic cup filled with 300 ml 10 mM MgSO4 mixed with 0.02% Silwet for a minute49. The inoculation experiments were performed twice in this study. In the first experiment, there were eight experimental units (4-cell inserts) and each contained two tomato plants. Units 1, 2, 5 and 6 contained uninoculated control plants, while units 3, 4, 7, and 8 contained plants inoculated with X. perforans. The second experiment employed a similar design, except that there were 10 experimental units, with units 1–5 uninoculated and units 6–10 inoculated.

Data collection

Data were collected nine times in each experiment: before inoculation (bi), 2 hours after inoculation (0 days after inoculation, dai), every 24 hours from 1 to 7 dai. Three types of data were collected, including disease rating, bacterial population size measurements, and hyperspectral image data (Figure 1). Disease-related data were collected based on the visual observation of tomato plants in each experimental unit. Then one to six leaves were removed from each experimental unit. After rating the disease severity of detached leaves, we used a hyperspectral benchtop imaging system (Resonon PIKA-L and PIKA-IR) to capture the hyperspectral images of each detached leaf. Then the leaves were processed to estimate the bacterial population size in the leaf tissue.

Disease rating

Two types of disease-related data were collected in this study to characterize the disease progress of BLS. First, we collected disease incidence data by estimating the percentage of leaves showing bacterial leaf spot in each experimental unit. Then we randomly selected five tomato leaves and rated the disease severity on each leaf50. We used a 0–5 scale to rate the severity data, where 0 indicates healthy, 1 indicates spot coverage between 0 and 10%, 2 indicates spot coverage between 10% and 30 %, 3 indicates spot coverage between 30 and 50%, without apparent dead tissues, 4 indicates spot coverage of more than 50% and some of the diseased tissue is dark and curled or decayed, and 5 indicates completely dry and curled or decayed tissue with numerous bacterial spots. Then a disease severity index was calculated as:

where NRi indicates the number of seedlings showing the corresponding disease level i; i ranges from 0 to 550. After rating the disease incidence and severity in each experimental unit, one to six leaves were removed from each experimental unit, and disease severity was rated for each detached leaf with the same 0–5 scale.

Hyperspectral image acquisition

Hyperspectral images of the detached leaves were collected using a RESONON benchtop system with Pika L (visible & near infrared: 400–1000 nm) and Pika NIR320 (shortwave infrared: 900–1700 nm). All leaf samples were scanned with both Pika L and Pika NIR320 cameras to collect hyperspectral image data ranging from 400 to 1700 nm. Before scanning, a camera (Pika L or Pika NIR320) was mounted on a tower, and the leaf samples were laid on a stage below the camera and four high-intensity halogen spotlights (Fig. S2). The system was set to reflectance mode, where the system measured the absolute reflectance of the leaf samples by applying dark correction and response correction using a reference tile provided by RESONON. The environmental lights were turned off, with only the imaging halogen lights on. A piece of black cotton fabric or a white calibration tile was placed on the stage, and the leaf samples were laid on the top of the background materials. During data acquisition, the stage moved in auto speed mode, and the camera scanned multiple lines simultaneously and translated into three-dimensional image cubes containing two-dimensional spatial and corresponding spectral data. Each scan yielded a bil (Band Interleaved by Line) data cube and a header file, which contained either 561 spatial pixel information (5.86 µm/pixel) at 300 VIS-NIR (385.63–1027.18 nm) wavelength bands or 164 spatial pixel information (30 µm/pixel) at 168 NIR (890.68–1719.81 nm) wavelength bands.

Bacteria growth curve

After the hyperspectral data from the detached leaves were acquired, each leaf was processed to estimate the bacterial pathogen population size (CFU per cm2 of leaf area). To begin with, five (1 cm diameter) round leaf discs were randomly subsampled from a leaf sample. The subsamples were sterilized with 75% ethanol for 45s, followed by a triple rinse with sterilized distilled water (SDW), and then sterilized with 10% bleach (0.5% sodium hypochlorite) solution for 30s, followed by triple rinse with SDW. Five surface-sterilized leaf discs were placed in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube and crushed by a disposable pellet pestle (Fisher brand) with 500 µL SDW. The leaf sap was collected as the fine leaf tissues were evenly suspended in the SDW, and it went through serial dilutions to obtain 10-1–10-8 of the original concentration. Two 20 µL aliquots of each diluted leaf sap were evenly spread on 200 mg/L rifampicin-R2A medium. The cultures were stored at 28 °C for two days and the bacterial colonies grown from each leaf sap concentration were counted and averaged. Finally, the original concentration of each leaf sap sample was calculated and the bacterial pathogen population size per cm2 of leaf area was estimated for each detached leaf sample.

Potentially confounding factors

In order to investigate the influence of potential confounding factors (including background materials and colors, scan precision, leaf size, and leaf structure) on leaf reflectance, additional leaves and corresponding hyperspectral images were collected.

The image data of 18 tomato leaves collected using dark fabric as background were used to test scan precision. The sample leaves included 8 leaves (4 uninoculated and 4 inoculated) from the first inoculation experiment and 10 leaves (5 uninoculated and 5 inoculated) from the second experiment. To test this hypothesis, each leaf was scanned twice at different position on the same stage and background. Leaf-level full spectra reflectance data of each leaf was compared between two scans, along with those of 18 randomly selected background pixels from each scan, using principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) with scikit-learn in Python51.

All leaf samples were collected with two background materials and colors: a piece of black cotton fabric, and a white calibration tile, placed on the stage. Therefore, each leaf yielded two sets of data: VISNIR (400–1000 nm) and SWIR (900–1700 nm) images with black cloth, and VISNIR and SWIR images with white tile. The image data of 16 tomato leaves were used to test this hypothesis, which included eight uninoculated and eight inoculated leaves collected at the end of each experiment. Leaf-level, spatially averaged full spectra reflectance data of each tomato leaf were compared across background materials, along with those of 16 randomly selected background pixels, using PCA and LDA (Figure S3).

The image data of 18 uninoculated tomato leaves collected with dark fabric background were used to test the leaf size hypothesis. Two leaves were collected from each of nine uninoculated plants, with a length of over 2.0 inches (big) or less than 1.5 inches (small). Therefore, the leaves collected from those nine uninoculated plants were labeled as “big” or “small” and plant group ID. Leaf-level full spectra data of each leaf were compared between and among nine groups, along with those of 18 randomly selected background pixels, using PCA and LDA.

The image data of nine uninoculated tomato leaves collected with dark fabric background were used to test the leaf structure hypothesis. Two leaves were collected from each of nine uninoculated plants. Five pixels were randomly selected from five structure areas from each leaf, including apex, margin, midrib, veins, and interveinal leaf tissues. The full spectra data of each pixel were compared between leaf structures, along with those of 45 randomly selected background pixels, using PCA and LDA.

Hyperspectral image analysis

In order to differentiate between infected tomato leaves and uninoculated healthy leaves and observe the physiological changes on tomato leaves during disease progression, HIS data collected at nine time points were analyzed with machine learning methods (Figure 1). HSI data were analyzed at three different levels, including VI (Vegetation Index), pixel, and whole image levels. Seven algorithms (Figure S4) including LDA, Supportive Vector Machines (SVMs), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB or XG Boost) were used with scikit-learn51 and xgboost52 in Python to perform feature selection and classify tomato leaf samples based on HSI data. During image data analysis, leaf samples from two classes (uninoculated healthy and infected) from nine data collection time points were used for ML training and testing, with 10-fold cross-validation. The training, validation, and testing set splitting ratio was 60:20:20. Then accuracy and F1 scores were compared to evaluate the performance of each model.

HSI images were cropped with Spectronon software (Spectronon Pro, Resonon, Bozeman, MT) to retain the leaf and minimum background pixels. The leaves were labeled by treatment, uninoculated or inoculated, and by data collection time points. The time points were further categorized into four stages: beginning (bi & 2hr ai), early (pre-symptomatic: 1–3 dai), mid (4–5 dai), and late (6–7 dai) stages. Thirty-six images containing 228 leaves were used for leaf-level analysis. Each leaf generated a mean spectral data set that averaged the pixel reflectance intensity at every wavelength band. There were 36 VISNIR and 36 SWIR leaf-level data from ‘beginning’, 54 VISNIR and 54 SWIR leaf-level data from ‘early’, 46 VISNIR and 46 SWIR leaf-level data from ‘mid’, and 92 VISNIR and 92 SWIR leaf-level data from ‘late’. There were four classes included in the ‘beginning’ dataset: uninoculated group bi, inoculated group bi, uninoculated 2hr ai, and inoculated group 2 hr ai. There were six classes in the ‘early’ dataset, including uninoculated 1 dai, inoculated 1 dai, uninoculated 2 dai, inoculated 2 dai, uninoculated 3 dai, and inoculated 3 dai. There were four classes in the ‘mid’ dataset, including uninoculated 4 dai, inoculated 4 dai, uninoculated 5 dai, and inoculated 5 dai. There were four classes in the ‘late’ dataset, including uninoculated 6 dai, inoculated 6 dai, uninoculated 7 dai, and inoculated 7 dai.

As for pixel-level analysis, nine classes of 72 pixels (648 VISNIR pixels and 648 SWIR) were randomly selected from 27 cropped image files containing 72 leaves collected at the end (7dai) of each experiment, which included class 0: green areas on the edge of uninoculated healthy leaves (GH-e), class 1: green areas in the interveinal areas on uninoculated healthy leaves (GH-iv), class 2: bacterial spots on the edge of infected leaves (BS-e), class 3: bacterial spots in the interveinal areas on infected leaves (BS-iv), class 4: abiotic spots on the edge of uninfected leaves (AS-e), class 5: abiotic spots in the interveinal areas on uninfected leaves (AS-iv), class 6: green areas on the edge of symptomatic tomato leaves (GS-e), class 7: green areas in the interveinal areas on symptomatic tomato leaves (GS-iv),and class 8: background (bg). The presence of abiotic spots and bacterial spots was verified by visual observation and culture isolation. Pixels were selected manually to ensure the same amount of leaf margin pixels and interveinal pixels were selected from each leaf, with the number ranging from four to six. The spectra data were saved in txt files using Spectronon Pro, and the raw data files were converted to csv files before data analysis.

For leaf-level full spectra analysis, the first and last wavelength bands were removed to exclude potential noises. Therefore, VISNIR spectra data files contained 298 bands (387.65 to 1024.90 nm, with an approximate 2 nm interval) and SWIR spectra data files contained 166 bands (895.52 nm to 1714.71 nm, with an approximate 5 nm interval). Data were normalized to fit a 0–1 scale. After data preprocessing, each pixel in each class contained 298 bands in VISNIR files and 166 bands in its SWIR files. LDA, SVM, KNN, RF, GBM, XGBoost, and MLP were employed to train the classification models. Hyperparameters (Fig. S4) for LDA, SVM, KNN, RF, and MLP were tuned with Grid Search, and those for GBM and XGBoost were tuned with Randomized Search51. The best combinations of hyperparameters were retained to train the classification model, with stratified 3-fold cross-validation repeated three times. The choice of 3-fold cross validation was made because of the small sample size. The accuracy and weighted F1 scores of each model were compared, and the best model was applied to predict leaf health on whole hyperspectral images. Important wavelength bands were extracted based on gini importance (mean decrease impurity) from corresponding RF, GB, or XGB models, whichever showed the best performance.

In leaf-level VI analyses, 14 vegetation indices (VIs, Table S1) that might be related to tomato disease stress were extracted from the pre-processed HSI data20,24,30,32,53. The above-mentioned classifiers were employed to train the classification models, and the performance was evaluated as described above. As for pixel-level full spectra analysis, the process was similar, except that 10-fold cross-validation was used instead of 3-fold, as the pixel data set size was bigger. The accuracy of classification models was compared using ANOVA with statsmodels54 followed by post-hoc analysis with scikit-posthocs55. The testing accuracy scores generated from classification models trained with leaf-level full spectra data were correlated with bacterial population in tomato leaf tissues averaged across two experiments during BLS disease progress. Pearson correlation coefficient and p-value were calculated with scipy.stats56.

The best classification models were applied to healthy and diseased whole leaf and living plant images collected at 7dai. The RF model trained with 7 dai VISNIR data and the SVM model trained with the SWIR model were applied to whole leaf images and living plants. The raw hyperspectral images were processed, and the reflectance data were extracted using spectral python (SPy) in Python57. The predicted results were compared with visual observations and bacterial population sizes (the ground truth data).

Data availability

The raw hyperspectral image data have been uploaded to Ag Data Commons: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/early-detection-bacterial-spot-disease-tomato-hyperspectral-imaging. Full evaluation metrics for all models are available upon request.

References

Gergerich, R. C. et al. Safeguarding fruit crops in the age of agricultural globalization. Plant Dis. 99(2), 176–187 (2015).

Liebhold, A. M., Brockerhoff, E. G., Garrett, L. J., Parke, J. L. & Britton, K. O. Live plant imports: the major pathway for forest insect and pathogen invasions of the US. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10(3), 135–143 (2012).

Waage, J. K. & Mumford, J. D. Agricultural biosecurity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363(1492), 863–876 (2008).

Savary, S., Ficke, A., Aubertot, J.-N. & Hollier, C. Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security (Springer, 2012).

Martinelli, F. et al. Advanced methods of plant disease detection. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35(1), 1–25 (2015).

Buja, I. et al. Advances in plant disease detection and monitoring: From traditional assays to in-field diagnostics. Sensors 21(6), 2129 (2021).

Dyussembayev, K., Sambasivam, P., Bar, I., Brownlie, J. C., Shiddiky, M. J. A. & Ford, R. Biosensor technologies for early detection and quantification of plant pathogens. Front. Chem.: 144 (2021)

Bohnenkamp, D., Behmann, J., Paulus, S., Steiner, U. & Mahlein, A.-K. A hyperspectral library of foliar diseases of wheat. Phytopathology 111(9), 1583–1593 (2021).

Cebula, Z. et al. Detection of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. Lachrymans on antibody-modified gold electrodes by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Sensors 19(24), 5411 (2019).

Kumar, R., Pathak, S., Prakash, N., Priya, U. & Ghatak, A. Application of Spectroscopic Techniques in Early Detection of Fungal Plant Pathogens. In Diagnostics of Plant Diseases (IntechOpen, 2021)

Li, Z. et al. Non-invasive plant disease diagnostics enabled by smartphone-based fingerprinting of leaf volatiles. Nat. Plants 5(8), 856–866 (2019).

De Vijver, V. et al. In-field detection of Alternaria solani in potato crops using hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 168, 105106 (2020).

Bhupathi, P. & Sevugan, P. Application of hyperspectral remote sensing technology for plant disease forecasting: An applied review. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 25(6), 4555–4566 (2021).

Mahlein, A.-K. Plant disease detection by imaging sensors–parallels and specific demands for precision agriculture and plant phenotyping. Plant Dis. 100(2), 241–251 (2016).

Oerke, E.-C. Remote sensing of diseases. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 58, 225–252 (2020).

Teke, M., Deveci, H. S., Haliloğlu, O., Gürbüz, S. Z. & Sakarya, U. A short survey of hyperspectral remote sensing applications in agriculture. In: 2013 6th International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies (RAST) (2013)

Lu, B., Dao, P. D., Liu, J., He, Y. & Shang, J. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sens. 12(16), 2659 (2020).

Gold, K. M. et al. Hyperspectral measurements enable pre-symptomatic detection and differentiation of contrasting physiological effects of late blight and early blight in potato. Remote Sens. 12(2), 286 (2020).

Gold, K. M., Townsend, P. A., Larson, E. R., Herrmann, I. & Gevens, A. J. Contact reflectance spectroscopy for rapid, accurate, and nondestructive Phytophthora infestans clonal lineage discrimination. Phytopathology 110(4), 851–862 (2020).

Veys, C. et al. Multispectral imaging for presymptomatic analysis of light leaf spot in oilseed rape. Plant Methods 15(1), 1–12 (2019).

Zhu, H. et al. Hyperspectral imaging for presymptomatic detection of tobacco disease with successive projections algorithm and machine-learning classifiers. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 4125 (2017).

Bebronne, R. et al. In-field proximal sensing of septoria tritici blotch, stripe rust and brown rust in winter wheat by means of reflectance and textural features from multispectral imagery. Biosyst. Eng. 197, 257–269 (2020).

Cubero, S., Marco-Noales, E., Aleixos, N., Barbé, S. & Blasco, J. Robhortic: A field robot to detect pests and diseases in horticultural crops by proximal sensing. Agriculture 10(7), 276 (2020).

Nguyen, C. et al. Early detection of plant viral disease using hyperspectral imaging and deep learning. Sensors 21(3), 742 (2021).

Wei, X., Johnson, M. A., Langston Jr, D. B., Mehl, H. L. & Li, S. Identifying optimal wavelengths as disease signatures using hyperspectral sensor and machine learning. Remote Sens. 13(14), 2833 (2021).

Yeh, Y.-H. et al. Strawberry foliar anthracnose assessment by hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 122, 1–9 (2016).

Abdulridha, J., Ampatzidis, Y., Kakarla, S. C. & Roberts, P. Detection of target spot and bacterial spot diseases in tomato using UAV-based and benchtop-based hyperspectral imaging techniques. Precis. Agric. 21, 955–978 (2020).

Fahrentrapp, J., Ria, F., Geilhausen, M. & Panassiti, B. Detection of gray mold leaf infections prior to visual symptom appearance using a five-band multispectral sensor. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 628 (2019).

Jones, C. D., Jones, J. B. & Lee, W. S. Diagnosis of bacterial spot of tomato using spectral signatures. Comput. Electron. Agric. 74(2), 329–335 (2010).

Lu, J., Ehsani, R., Shi, Y., de Castro, A. I. & Wang, S. Detection of multi-tomato leaf diseases (late blight, target and bacterial spots) in different stages by using a spectral-based sensor. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 1–11 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Early detection of tomato spotted wilt virus by hyperspectral imaging and outlier removal auxiliary classifier generative adversarial nets (OR-AC-GAN). Sci. Rep. 9(1), 1–14 (2019).

Pane, C., Manganiello, G., Nicastro, N. & Carotenuto, F. Early detection of wild rocket tracheofusariosis using hyperspectral image-based machine learning. Remote Sens. 14(1), 84 (2021).

Hahn, F. Actual pathogen detection: sensors and algorithms-A review. Algorithms 2(1), 301–338 (2009).

Zhang, M. & Qin, Z. Spectral analysis of tomato late blight infections for remote sensing of tomato disease stress in California. In IGARSS 2004. 2004 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (2004)

Courbier, S. et al. Far-red light promotes Botrytis cinerea disease development in tomato leaves via jasmonate-dependent modulation of soluble sugars. Plant Cell Environ. 43, 2769–2781 (2020).

Kalaitzoglou, P. et al. Effects of continuous or end-of-day far-red light on tomato plant growth, morphology, light absorption, and fruit production. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 322 (2019).

Tan, T. et al. Far-red light: A regulator of plant morphology and photosynthetic capacity. Crop J. 10, 300–309 (2022).

Marble, C. B. et al. Z-scan measurements of water from 1150 to 1400 nm. Opt. Lett. 43(17), 4196–4199 (2018).

Prieto-Blanco, A., North, P. R. J., Fox, N. & Barnsley, M. J. Satellite estimation of surface/atmosphere parameters: a sensitivity study. In Global Developments in Environmental Earth Orbservation from Space. Proceedings of the 25th EARSeL Symposium. (Millpress Science Publishers, 2006).

Schornack, S., Minsavage, G. V., Stall, R. E., Jones, J. B. & Lahaye, T. Characterization of AvrHah1, a novel AvrBs3-like effector from Xanthomonas gardneri with virulence and avirulence activity. New Phytol. 179(2), 546–556 (2008).

Schwartz, A. R., Morbitzer, R., Lahaye, T. & Staskawicz, B. J. TALE-induced bHLH transcription factors that activate a pectate lyase contribute to water soaking in bacterial spot of tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114(5), E897–E903 (2017).

Aung, K., Jiang, Y. & He, S. Y. The role of water in plant–microbe interactions. Plant J. 93(4), 771–780 (2018).

Saad, A. G., Pék, Z., Szuvandzsiev, P., Gehad, D. H. & Helyes, L. Determination of carotenoids in tomato products using Vis/NIR spectroscopy. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2021, 27–31 (2021).

Liu, L.-Y., Huang, W.-J., Rui-liang, P. U. & Wang, J.-H. Detection of internal leaf structure deterioration using a new spectral ratio index in the near-infrared shoulder region. J. Integr. Agric. 13, 760–769 (2014).

Roman, A. & Tudor U. "Multispectral satellite imagery and airborne laser scanning techniques for the detection of archaeological vegetation marks. In 2016. Landscape archaeology on the northern frontier of the roman empire at porolissum: an interdisciplinary research project 141–152 (Mega Publishing House, 2016)

Blanch-Perez-del-Notario, C., Saeys, W. & Lambrechts, A.. Hyperspectral imaging for textile sorting in the visible–near infrared range, J. Spectral Imag. 8 (2019).

Kouw, W. M. & Loog, M.. An introduction to domain adaptation and transfer learning. arXiv:1812.11806 (2018).

Yan, K., Guo, X., Ji, Z. & Zhou, X. Deep transfer learning for cross-species plant disease diagnosis adapting mixed subdomains. In IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics (2021)

Hert, A. P. et al. Suppression of the bacterial spot pathogen Xanthomonas euvesicatoria on tomato leaves by an attenuated mutant of Xanthomonas perforans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75(10), 3323–3330. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02399-08 (2009).

Chester, K. S. Plant disease losses: their appraisal and interpretation. Plant Dis Rep. 193(Suppl), 190–362 (1950).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference On Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (2016)

Kureel, N., Sarup, J., Matin, S., Goswami, S. & Kureel, K. Modelling vegetation health and stress using hypersepctral remote sensing data. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8(1), 733–748 (2022).

Seabold, S., & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (2010)

Terpilowski, M. A. scikit-posthocs: Pairwise multiple comparison tests in Python. J. Open Sour. Softw. 4(36), 1169 (2019).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17(3), 261–272 (2020).

Boggs, T. Spectral Python (SPy)—Spectral Python 0.14 Documentation. http://www.spectralpython.net/ (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeff Burr (Virginia Tech) for providing greenhouse tech support for this study. This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture (2021-67021-34037). All institutional guidelines at Virginia Tech for handling tomato plants were followed. The tomato plants used in this research were obtained from a licensed seed company and do not contain transgenic materials. For non-transgenic plants, no additional permission is required for handling these tomato plants according to Virginia Tech biosafety guidelines. This project used seeds from a commercial cultivar of tomato, which fully comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. designed and conducted the experiment. X.Z. analyzed the data. X.Z., B.V, and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Vinatzer, B.A. & Li, S. Hyperspectral imaging analysis for early detection of tomato bacterial leaf spot disease. Sci Rep 14, 27666 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78650-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78650-6

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in plant disease detection: challenges and opportunities

Plant Methods (2025)

-

Assessment of slow blighting and development of alterneria blight in different genotypes of Bael

Discover Plants (2025)

-

Hyperspectral Detection and Differentiation of Various Levels of Fusarium Wilt in Tomato Crop Using Machine Learning and Statistical Approaches

Journal of Crop Health (2025)

-

Early prediction of disease in soybeans by state-of-the-art machine vision technology

Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology (2025)