Abstract

In the current investigation, elemental boron was added to form a series of Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx Compositionally Complex Alloys (CCAs). Alloying was done via vacuum arc melting in amounts of 0.0, 5.3, and 10.6 at.%. From the thermodynamic parameters, adding B to the base alloy increased the system’s entropy. The microstructure of the prepared CCAs was characterized using scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The mechanical properties of CCAs as related to microstructure were assessed. According to XRD results, B-based intermetallic phases were obtained in the prepared CCAs, which were binary as Ti3B4 and ZrB2 and ternary as FeNbB and Nb3Co4B7. These intermetallic phases notably provided strengthening effects to the B-added alloys. Ti48Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B5.3 CCA showed the most homogenous microstructure obtained by the arc melting process. Adding B increased Young’s modulus from 141 GPa (without B) to 195 GPa and 260 GPa with 5.3 and 10.6 at.%B, respectively. Hardness also increased from 502 to 606 HV with 5.3 at.% B and to 648 HV with 10.6 at.%B. Accordingly, the wear resistance increased with B addition where 10.6 at.%B sample showed the lowest wear rate among the other conditions. However, 5.3 at.% B was nominated as the optimum addition amount due to its notable microstructure homogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In conventional alloys, the mechanical properties of the alloy are determined based on the properties of a single element. For example, the carbon content of ferritic steels with low levels of carbon is the key component that determines their mechanical properties1,2,3. For solid solution strengthening, carbon is used as an interstitial solute element; nevertheless, the bulk of the strength is contributed by iron. Similarly, in Ti- or Al-based alloys, the proportion of Ti/Al makes up the alloy properties. Titanium alloys lose their strength when tempered at 350–550 °C, negatively affecting their performance in several high-temperature applications. High entropy alloys (HEAs) were developed in 2004 to solve similar problems for several high-temperature alloys4.

HEAs are generally defined as alloys of five or more elements combined in equi- or near-equi-molar proportions5. Being solid solutions alloys, HEAs grasped the attention due to their high strength, good thermal stability, and corrosion resistance6,7,8,9. The thermal stability of HEAs was proved to be controllable by incorporating elements that form stable phases. Pradhan et al.10 replaced Ni in the Cantor alloy (CoCrFeMnNi)) with Mo (σ-phase forming elements) and interestingly obtained four phases that were stable up to the melting point. Refractory HEAs were designed to combine high strength with superior thermal stability11. Kumar et al.12 in their study on MoNbTa0.5Ti0.5W refractory HEAs observed that the elemental segregation of W and Ta (in the dendritic region) and that of Mo, Nb, and Ti in the (inter-dendritic area), led to solid solution hardening that raised the microhardness of these regions to 4.8 and 5.75 GPa respectively.

Because there is no one dominant component, the hardness and strength of HEAs are determined by their structural kinds rather than the HEAs themselves13. Ni with its FCC crystal structure induces a more lattice distortion effect in HEAs, which prevents crystal dislocation and improves strain hardening. On the other hand, Fe is an α-phase with a BCC crystal at room temperature but transforms to FCC-phase at 910 °C, aiding in solid solution evolution and strength14. Based on this concept, BCC-HEAs may be chosen if high-yield strengths are sought; on the other hand, FCC-HEAs are preferred when low-yield strengths (high plasticity) are desired. Combining the two different structures in two-phase high-energy alloys (HEAs) leads to the creation of balanced properties, such as high strength and exceptional ductility, called the cocktail effect of HEAs. The blending of several traits creates the “cocktail” effect. According to Cao et al.15, the ‘cocktail’ effect in HEAs was induced mainly by local dislocation brought on by the metastable crystal structure and lattice distortion brought on by substantial atomic size variations16.

Recent investigations on Ti-based HEAs have focused on varied compositions and processing techniques, revealing intriguing phase stability and mechanical properties. These studies have explored different combinations of Ti with transition metals, aiming to optimize the alloys’ microstructure and enhance their performance. However, most of the work done on HEAs is in the laboratory stage, and not generally employed in the industry due to the difficulty of obtaining only solid solutions in the alloy structure17. Besides, intermetallic phases are frequently needed for strengthening purposes to achieve the service requirements. Some research works18,19 developed multicomponent alloys that contain intermetallic phases and were deviated from HEAs. According to Manzoni and Glatzel18, CCAs are sometimes obtained accidentally if the preparation conditions of HEAs (composition, cooling rate, etc.) are not satisfied. On the other hand, some researchers prepared CCAs intentionally to enhance the mechanical properties via intermetallic formation20. It has been reported that incorporating p-block elements such as nitrogen (N), carbon (C), and boron (B) resulted in the development of new high-entropy materials such as high-entropy nitrides, carbides, and borides21,22. Small B additions to Ti alloys improved their processibility thus leading to dramatic cost reduction23. B is entirely soluble in the Ti- liquid phase but has negligible solubility in the solid phase and hence eliminates the embrittlement problem caused by other interstitial elements such as H, C, or O24,25. Nb, Zr, Fe, Co, and Ni can also be added as alloying elements to the Ti matrix to improve their properties26,27,28,29. Ti-Fe and Ti-Fe-Co alloys with high mechanical properties and good ductility were produced at a low cooling rate following pre-melting in an arc furnace30. Ti-13Nb-13Zr, for example, is a near beta-Ti alloy which is disadvantaged by its low hardness when used for hip endoprostheses head and acetabulum applications31.

The TiNbZr group is classified as a beta-phase alloys based on its elemental composition. Ti, Nb, and Zr exhibit a beta-like crystal structure at room temperature, characterized by a close-packed hexagonal arrangement of atoms32. The ternary system of Ti25Nb25Zr alloy is shown in Fig. 132. Ti-Nb and Ti-Zr-Nb alloys exhibit significantly higher hardness compared to cp-Ti grade 2, while their elastic modulus is either lower or comparable (e.g., Ti-12Nb). As a result, they are expected to offer improved wear resistance and longer service life as biomedical materials33. The Ti-Nb-Zr alloy system is widely regarded as one of the top candidates for developing safe and highly competitive biomedical alloys. However, their broader use is restricted by relatively low strength, hardness, and wear resistance. A significant enhancement in strength can be achieved by creating metal matrix composites reinforced with high-strength ceramic particles. Among the most promising reinforcing materials is TiB fiber, which has excellent compatibility with the titanium matrix, a similar coefficient of thermal expansion, and good thermal stability34. Another study added TiB2 as a reinforcement to TiNbZr alloy to increase the strength of the alloy35.

Ternary diagram of Ti-25Nb-25Zr32.

The design of HEAs is guided by four key principles: the high-entropy effect, lattice distortion, sluggish diffusion, and the “cocktail” effect36. The design approach of Ti-base HEAs, such as Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx, involves a strategic selection of elements based on targeted properties like mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and stability at high temperatures. Titanium forms the base, offering excellent strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance, while Nb improves mechanical strength and toughness, especially at lower temperatures and corrosion resistance37,38. Zirconium enhances both corrosion resistance and strength, stabilizing the β-phase for better ductility37. Nickel also stabilizes the β-phase, improving corrosion and oxidation resistance at higher temperatures. Cobalt contributes to wear resistance and elevated temperature strength, while iron enhances toughness, although it must be carefully balanced to avoid brittle phases. In titanium alloys without B, typical intermetallic phases such as Ti2Ni can form, known for their high strength and hardness but often exhibit limited ductility and toughness. While these intermetallics enhance overall strength at elevated temperatures, they can lead to brittleness under stress or impact. The presence of B often leads to the formation of boride phases that can further enhance mechanical properties while maintaining a high degree of entropy, that is crucial for the overall performance and reliability of the alloy in demanding environments. These elements are chosen to enhance the mechanical properties of Ti-base HEAs39.

Boron solubility is less than 1 at.% in beta-Ti and alpha-Ti40. As a result, B is largely insoluble in titanium, leading to formation of TiB particles30,39. Boron addition typically leads to grain refinement through several mechanisms, such as promoting nucleation during solidification by altering solidification pathways, which results in finer grains. Additionally, the formation of boride compounds can act as grain boundary pinning agents, preventing the growth of larger grains during processing and heat treatments. Boron also modifies the thermodynamic properties of the alloy, stabilizing finer microstructures during solidification and cooling processes. As boron content increases, it influences the solidification behavior of the alloy by promoting the formation of boride compounds, which refine the microstructure. This refined structure typically features smaller, more equiaxed grains due to heightened nucleation rates during solidification. Conversely, lower B levels may lead to diminished nucleation and the formation of larger, columnar grains, particularly under conditions that favor directional solidification. Moreover, the cooling rate during solidification plays a critical role; higher B levels can promote rapid cooling, while lower levels may lead to slower cooling rates, facilitating the development of larger, columnar grains41.

Many Ti-based CCAs still face challenges related to specific mechanical properties under extreme conditions. However, much of the research has focused on conventional CCA designs, which creates a gap in exploring novel compositions that leverage titanium’s inherent advantages while introducing new functionalities. The present investigation seeks to address this gap by developing a novel Ti-based CCAs system that incorporates a unique combination of alloying elements. By systematically analyzing the microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties of this new alloy, this paper aims to provide insights that could lead to enhanced performance in demanding applications36. In the current research, B was added to enhance the mechanical properties of novel Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs via the intended formation of intermetallic phases while maintaining the high entropy effect. The thermodynamic parameters of the CCAs were calculated to evaluate the entropy level. Also, the microstructures were examined using SEM, EDX, and TEM. The mechanical properties of the prepared CCAs were assessed using Young’s modulus evaluation by pulse-echo method, hardness measurements, and wear property testing. The results were then related to the microstructure characteristics, including the B-based intermetallic phases.

Experimental work

Materials

Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs were prepared by the vacuum arc melting method (VAM). Ti, Nb, Zr, Ni, Co, Fe, and B were added as pure metals. Model (1250 LHD-China) vacuum arc-melting furnace prepared the different compositions. This furnace has three units: a control unit, a melting chamber, and a chiller. In VAM, the process starts by positioning the pure metallic pieces into the crucible (water-cooled) and then evacuating the melting chamber to avoid the reactivity of the constituting elements with air, especially Ti, which has a high oxygen affinity. Once the required vacuum degree is reached, an inert gas (argon) is injected into the chamber. A high voltage is applied between the tungsten electrode and the copper crucible. When the gun touches the crucible, it creates a spark that ignites an intense arc, thus melting the charge. By increasing the applied current, the temperature can be boosted to around 3000 C42. The melt is electromagnetically stirred to ensure proper mixing of different constituents, producing homogeneous samples. Finally, a disc sample of 10 mm thickness and 80 mm diameter was obtained. Three alloys, Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx (where x is 0.0, 5.3, and 10.6 at.% B), were obtained. The melting chamber and the prepared sample are presented in Fig. S1.

Investigation of Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs

Microstructure characterization

The Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs samples were cut and ground using SiC emery papers up to grid 1200 then polished by alumina paste of 0.3 µm, and finally etched using 7%HF, 8%HNO3 and the rest is distilled water for microstructure characterization. The microstructure of Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs was studied using an SEM (Quanta FEG 250 with field emission gun, FEI − Netherlands) and the elemental distribution was detected using SEM & EDX system (JEOL Ltd. JSM-7100F-Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K. Ultra-Dry). A transmission electron microscope (TEM) model (JEOL Ltd. JEM-2100Plus) was also used to investigate the alloy crystallinity further.

Phase identification

The phase identification was performed to recognize the formation of the phases in the different CCAs using an X-ray diffractometer model (D8 Discover, Bruker) with Cu Kα radiation λ equal to 1.54 A, 40 kV.

Hardness measurements

The influence of B addition on the hardness of CCAs was evaluated using a 10 kg Vickers hardness tester (model Zwick/Roell (ZHU250)). An average of five readings was considered.

Wear resistance

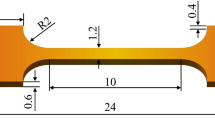

The wear test was performed using a load of 10 kg and a speed of 1 m/s with 0.9 km sliding displacement (T-01 M Pin-on-Disk testing machine). A schematic illustration of the wear test is shown in Fig. 2. The coefficient of friction (COF) was calculated by using Eq. (1), and the wear rate (WR) using Eq. (2)43.

where F is the tangential friction force, and N is the normal applied load44

where Δ w is the weight loss measured in grams, and Ls is the sliding distance in kilometers.

Young’s modulus

Young’s modulus was measured by pulse-echo method at 5 MHz frequency and room temperature using sensitivity balance model Mettler H 72, capacity 160 g, readability 0.1 mg. with ultrasonic flaw detector model USM3. The Young’s modulus was calculated using several equations from Eqs. (3) to (7). Longitudinal modulus (L) was calculated by Eq. (3), where the shear modulus (G) by Eq. (4) and the bulk modulus (K) by Eq. (5). The Young’s modulus (E) by Eq. (6) and Poisson’s ratio (σ) by Eq. (7)43.

Results and discussions

Alloy design and thermodynamic parameters of the prepared CCAs

Similar to HEAs, the classical Hume-Rothery rules45,46 can be used to determine the empirical thermodynamic parameters that rely on the mixing enthalpy (\(\Delta {H}_{mix}\)), the mixing entropy (\(\Delta {S}_{mix}\)), the atomic size mismatch (\(\delta\)) and electro-negativities to comprise the solid-solution creation between elements in the CCAs. The atomic size difference (d) is essential to the physical characteristic of a solid solution state. Zhang et al.45 defined the parameter (\(\delta\)) instead of (d) to reflect the overall impact of the atomic size mismatch (in multi-component alloys) between the primary elements. According to Wang et al.47, the parameter of δ was thought to be related to the strain energy but without any physical verification. The parameter δ can be defined as follows:

where \({c}_{i}\) and \({r}_{i}\) are the atomic fraction of the \(i\) element of the individual alloy component, respectively. The mixing enthalpy of the medium entropy and high entropy alloys with \(n\) elements were determined by Takeuchi et al.48 from the following:

where \({\Omega }_{ij}\) denotes the regular melt-interaction parameter between the ith and the jth elements, and cj denotes the jth molar fraction of the \(j\) component, which \({\Omega }_{ij}\) denotes estimated from the following:

where \({\Delta H}_{AB}^{mix}\) denotes the binary alloys’ mixing enthalpy due to the Miedema model48. The mixing entropy of the disordering solid solution is determined by44:

where R denotes the universal gas constant that has a value of 8.314 J/mol K. To further characterize the structural relaxation behavior, another criterion with a thermodynamics-originated parameter \(\Omega\) that can be written as follows49:

where \({T}_{m}\) represents the average melting temperature for the medium and high entropy systems computed using the following equation as a first-order estimation50:

The ΔHmix, ΔSmix, Ω and δ% values exist in Table 1. The \(\delta \%\) values are higher for all investigated alloys than 6.6%, which is not a stable solid solution according to Zhang’s criteria45. The mixing enthalpy of all alloys is between −16.80 to −18.97 kJ/mole. Also, the mixing entropy is increased from 11.31 for 0 at.%B, to 13.39 for 5.3 at.%B, and to 14.16 for 10.6 at.%B. The \(\Omega\) is related to \(\Delta {H}_{mix}\) and \(\Delta {S}_{mix}\). Formation of solid solution when larger than 1.1, and creation of intermetallic components when less than one. Thus, from Table 1, \(\Omega\) enhances the solid solution phase formation. When t \(he \Delta {S}_{mix }/R\) is greater than or equal to 1.5, the alloy can be considered as high entropy CCA, (HECCA), and when it is within 1 and 1.5 it is named medium entropy CCA (MECCA). The value of \(\Delta {S}_{mix }/R\) is equal to 1.36 for Ti53.3Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7 alloy. Thus, this alloy is MECCA For Ti48Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B5.3 and Ti42.7Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B10.6 alloys, \(\Delta {S}_{mix }/R\) is equal to 1.61 and 1.70, respectively. Thus, these alloys are HECCAs. According to Guo et al.51, it is important to calculate the valence electron concentration (VEC) to estimate the stability of the phases in HEAs. In HEAs, if VEC ≤ 7.30, then the BCC structure is dominant, while the dual phase structure HEAs (BCC + FCC) have (7.30 < VEC < 7.72), and those where (VEC ≤ 7.30), are FCC-HEAs. Table 1 shows that the total VEC of all the investigated samples is lower than 7.3, indicating that the main phase is BCC, whose stability increases by adding the elemental B.

Phase identification

The XRD patterns of the investigated CCAs are provided in Fig. 3 and Table 2. The base alloy is composed of a cubic structure (Ni42Zr58) reported in50 as the main phase with some other phases that are composed of (Ti0.5225Zr0.2827Ni0.1948)52, Co5Zr, and others. Adding B decreased the XRD-qualitative percentage of Ni42Zr58 (from 64 to 41 at 5% B and down to 30 at 10.6 at.%), and encouraged the formation of borides. It has been reported that both Nb and Zr interact with B via the eutectic reaction thus producing ZrB2 and NbB2 in binary reactions53,54. Similarly, Ni and B have been reported to form borides55. Complex borides such as FeNbB and Nb3Co4B7 were also detected. According to54,55, these borides are expected to contribute to alloy strength. Transition metal diborides such as TiB2 and ZrB2 showed high hardness and elastic modulus. Figure 4a provides the TEM image of the cast Ti48Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B5.3 CCAs. This TEM micrograph represents complete crystallinity. It is also clear from TEM images that microstructure coarsening occurred, and the samples became less homogeneous, with increasing the B to 10.6 at.%, Fig. 4b.

Microstructure investigation

Additions of B to Ti- alloys with certain limits have been attempted with beneficial effects such as microstructure refinement in pure Ti56, near alpha alloys such as Ti–6Al–2Sn–4Zr–2Mo57, beta Ti- alloys58, and Ti-6Al-4V alloy59. Figure 5 shows the SEM micrographs of the cast Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs, where their magnified images were provided in Fig. 6. It can be observed here that CCA alloy containing 5.3 at.%B has a more homogeneous microstructure than that with 10.6 at. It is also notable that the presence of B in Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs led to great changes in morphology and grain size as mentioned in the literature before 59. The grains became equiaxed to columnar with a decrease in size by 5.3 at.% additions. However, the increase to 10.6 at.% B led to grains coarsening.

The microstructure of the obtained CCAs shown in Fig. 6 was too complex to identify the phases separately. The following EDX analysis of the prepared CCAs shows that some phases overlap thus, they cannot be distinguished using color contrast. Figure 7 shows the EDX elemental mapping of Ti53.3Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7 CCA. It is observed that the microstructure of this alloy contains some segregation of Ti besides the main Ni42Zr58, Fe0.2Ni4.8Ti5, and Co5Zr phases. However, this segregation is very common in the vacuum arc melting process of HEAs and CCAs4,5. The corresponding EDX micrograph that locates some spots, and their analysis are shown in Fig. 8 and Table 3 respectively.

The dark phase in Spot (1) has high Ti, while the white phase in Spot (2) has a high Nb content. The white–grey phase in Spot (3) has high Ni and Zr (possibly Ni42Zr58), while the dark gray phase in Spot (4) and the lighter gray phase in Spot (5) have high Zr, Ni, Co, and Fe. Spots 4 and 5 may contain (Co5Zr and FeNiTi phases overlapping each other).

The elemental mapping of Ti48Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B5.3 CCA, is presented in Fig. 9. This map emphasizes the good distribution of B. Figure 10 and Table 4 present the EDX spots location and their analysis respectively. The dark phase in Spot (1) has high B, Ni, Co, and Fe, while the white–gray phase in Spot (2) has high Zr and Ni. The white phase in Spot (3) has high B and Nb (might be phase NbB2 as discussed in the XRD section) along with some pure Nb. The grey phase in Spots (4) and (5) contains high B, Zr, and Ni (might be ZrB2 with Ni42Zr58). Generally, a good distribution of the phases could be obtained in 5.3 at.% B CCA, based on Fig. 9, except for some segregation of Nb as observed in spot 2. In this map, a network of borides (Ti, Ni, Nb, Zr, and Fe) can be observed which is good in terms of the expected positive effects of these intermetallic phases on the mechanical properties.

Figure 11 and Table 5 represent an example of the EDX analysis of Ti42.7Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B10.6 CCA. From this example, the black phase (Spot #1) has Co, Ni, Fe, and B content. The white phase (Spot #2) is mainly Nb with some B. The dark grey phase (Spot # 3) has high Co, Zr, Ni, and Fe. The light grey phase of Spots #4 and #5, has Nb and B. Compared to Ti48Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B5.3 CCA, inadequate distribution of the phases along with coarser grains can be observed in Ti42.7Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7B10.6 CCA.

Mechanical properties of Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx

As a consequence of the observed influence of B on the microstructure of the CCAs, the mechanical properties were considered.

Hardness

Most research works focused on improving the hardness of beta-Ti alloys through thermomechanical effects. Using more advanced digital control systems to precisely select processing parameters, such as heat treatment and complex microstructure building, could be a future development path55,60. In the current experiments, significant improvement was noticed in the hardness of CCAs by adding 5.3 at.% B and 10.6 at% in 20% and 30%, respectively. Hardness increased from 502 to 606 HV with 5.3 at.% B and to 648 HV with 10.6 at.%B. This improvement in the hardness with B addition can be principally owed to the formation of new B-based intermetallic phases, shown in XRD results. These boride phases such as BNi2, NbB2, Ti3B4, TiB12, and ZrB have been reported to be stable strengthening phases54,55. Consequently, increasing the B content supports formation of these phases and hence increases the alloys’ hardness.

Wear resistance

The wear mechanisms generally occurring in Ti-alloys include oxidation, adhesive, abrasive, and layered wear61,62. On the other hand, different loading sliding velocities, matrix materials, and ambient temperature conditions alter the wear mechanisms63. The sliding wear resistance is proportional to the alloy’s hardness, according to Archard’s laws. Furthermore, the COF can influence the material’s wear resistance. Generally, a low friction coefficient benefits the material’s wear resistance. Some researchers modified beta-Ti to reduce the COF on the material surface to 0.42 in Ti-13Zr-13Nb-0.5B alloy26.

The coefficients of friction (COF) values were recorded for the current tests, as shown in Fig. 12. The CCAs without B (S1) recorded a COF of about ~ 0.3. Alloying with 5.3 at.% B showed almost no change in the value of COF (~ 0.33) while increasing the B to 10.6 at.% led to a significant increase in the COF to (~ 0.5). Regarding the wear rate (WR) of the tests performed at 0.9 km sliding distance, speed of 1 m/s, and a load of 10 kg, increasing the B content decreased the WR from ~ 0.13 to ~ 0.03 with 5.3 at.% B addition and then to ~ 0.004 at 10.6 at.% B. This results in line with the hardness values, which also increased with B addition, due to the formation of boride phases.

Here, it is worth noting that B addition decreased the WR while increasing the friction coefficient. This seems contradicting to the previous literature53,55, where it was mentioned that improving wear resistance relies on decreasing COF. This can be explained through the recent Kato et al. work61, where it was stated that multiphase alloys such as Fe, Cu, and Al systems have phases that differ in hardness and oxidation behavior. When these multiphase surfaces are rubbed in the air by another solid surface, the generated oxides differ in their types and influence the friction coefficient value. However, the general behavior of the alloy during friction in the classical alloying systems is related to the principal element (Fe, Al, etc.). In the current investigation, the process is more complex since we have HEAs with multi-principal constituents (Ti, Nb, Zr, Ni, Co, and Fe) where the value of COF cannot be related to a single phase. Some of these oxides can decrease COF, while others may exhibit negative effects. This is evident following the behavior of COF curves in Fig. 12, in which an almost stable trend is observed in S1 while adding B resulted in the formation of other compounds and phases, affecting COF stability during the wear test. According to Luo et al.64, the tribological performance of CCAs in different environments still needs more research to widen the practical application of CCAs as a coating material.

Young’s modulus

It has been reported that the dispersion of hard particles, such as carbides or borides can significantly raise Young’s modulus of Ti alloys35. It is worth noting that in CCAs, mixing the main elements in equimolar proportion, results in lattice distortion, leading to an increase in yield strength due to the lattice’s higher resistance to dislocation movement65. Due to strong solid solution strengthening, equiatomic TiNbZr, for example, combines good strength and excellent ductility35,65. TiNbZr alloys have Young’s modulus of about 48–80 GPa, which is significantly lower than that of Ti-6Al-4V (110 GPa), 316L stainless steel (200 GPa), and Co-Cr alloys (210–232 GPa)65. The Young’s modulus in the current work was measured by physical methods (ultrasonic) due to the small size of the prepared samples. The measured values of Young’s modulus were in good agreement with the hardness values obtained for the different alloys. Adding B increased Young’s modulus from 141 GPa (without B) to 195 GPa and 260 GPa with 5.3 and 10.6 at.%B, respectively. These results were expected due to the strengthening boride phases observed in the XRD patterns of the different alloys. These five phases: BNi2, NbB2, Ti3B4, TiB12, and ZrB contributed to strengthening the prepared CCAs.

Assessment of impact toughness

To assess the impact toughness of the three CCAs, microhardness was measured for the different samples. According to the early investigation by Nihara et al.66, the impact toughness can be estimated using Eq. (14) as long as the cracks are observed clearly during the microhardness test. Although this equation is more applicable to hard composites and intermetallic alloys, it has been used to estimate the fracture toughness of brittle samples67. The crack geometry, for which the relation between fracture toughness, crack size, and other relevant parameters given by Eq. (14) is known as “Palmqvist crack”.

where KIC is the fracture toughness, Φ is a constraint factor taken from68, H is the average microhardness, E is Young’s modulus, d is the average diagonal length of indentation, and L is equal to the total length of the Palmqvist crack. Table 6 lists the average microhardness values, indentations, and the corresponding KIC wherever a crack could be detected. It is notable that sample “S3” which has 10.6 at.% B, and exhibited the highest hardness and Young’s modulus showed brittle behavior, indicated by the indentation-induced cracking. On the other hand, sample “S2” with a moderate amount of B (5.3 at.%), where a more homogeneous microstructure was observed, showed no cracks.

Conclusions

The current work investigated the effect of B additions (5.3 and 10.6 at.%) on the metallurgical characteristics of a novel cast Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx CCAs. It was concluded that:

-

1.

Adding B to Ti53.3Nb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7 CCAs decreased the total VEC thus enhancing the stability of the BCC structure, which is the main phase.

-

2.

Formation of BNi2, NbB2, Ti3B4, TiB12, and ZrB intermetallic phases caused second phase strengthening.

-

3.

The hardness increased from 502 to 606 HV with 5.3 at.%B and to 648 HV with 10.6 at.%B. Consequently, enhanced wear properties were obtained.

-

4.

Young’s modulus increased from 141 to 195 GPa and 260 GPa with 5.3 and 10.6 at.% B, respectively.

-

5.

Increasing the amount of B to 10.6 at.% led to brittleness that was indicated by cracking during the microhardness test. Therefore adding 5.3 at.% B is recommended to obtain homogeneous CCAS with enhanced strength.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wang, X. F., Zhang, Y., Qiao, Y. & Chen, G. L. Novel microstructure and properties of multicomponent CoCrCuFeNiTix alloys. Intermetallics 15, 357 (2007).

Shivam, V., Basu, J., Manna, R. & Mukhopadhyay, N. K. Local composition migration induced microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of non-equiatomic Fe40Cr25Ni15 Al15Co5 medium-entropy alloy. Metall. Mater. Transact. A 52A, 1777 (2021).

Shivam, V., Kar, S., Mandal, G. K., Srivastava, V. C., Mukhopadhyay, N. K. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Fe‑containing high and medium entropy alloys: Recent advances and future prospects, Trans. Indian Inst. Met., (2023).

El-Hadad, S. High entropy alloys: The materials of future. IJMTI 2, 67–84 (2022).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. D. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Hedya, S. A. et al. Effect of Si/Ti additions on physico-mechanical and chemical properties of FeNiCrCo high entropy alloys manufactured by powder metallurgy technique. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 32, 2648–2664 (2022).

Mahmoud, E. R. I., Mohamed, L. Z., Gepreel, M. A., Ebied, S. & Abdelfatah, A. Corrosion behavior of cold-rolled and solution-treated Fe36Mn20Ni20Cr16Al5Si3 HEA in different acidic solutions. Materials 15, 7319 (2022).

Ibrahim, M., El-Hadad, S., Khalifa, W. & Shoeib, M. Effect of Ti addition and heat treatment on electrochemical properties of cast Fe35Mn31Ni18Al13Tix HEAs. Inter. Metalcast. 17, 888–899 (2023).

Mohamed, L. Z., Abdelghafar, K. A., Aly, H. A., Gaber, G.A., Comparative studies of Cr/Ti additives for Cu40Mn25Al20Fe5Ni5 HEA on microstructure and corrosion behavior in HNO3 solution, Int. J. Metalcasting, (2023).

Pradhan, P., Shadangi, Y., Shivam, V. & Mukhopadhyay, N. K. Powder metallurgical processing of CrMnFeCoMo high entropy alloy: Phase evolution, microstructure, thermal stability and mechanical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 935, 168002 (2023).

Abolkassem, S. A., El-Hadad, S., Mohamed, L. Z., Synthesis and characterization of WNiFeCo, WNiFeMo, and WNiFeCoMo compositional complex alloys manufactured by powder metallurgy technique. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. (2024).

Kumar, S., Linda, A., Shadangi, Y. & Jindal, V. Influence of micro-segregation on the microstructure, and microhardness of MoNbTaxTi(1–x)W refractory high entropy alloys: Experimental and DFT approach. Intermetallics 164, 108080 (2024).

Ujah, C. O., Popoola, A. P. I., Popoola, O. M., Afolabi, A. E. & Uyor, U. O. Mechanical and oxidation characteristics of Ti20-Al16-V16-Fe16- Ni16-Cr16 high-entropy alloy developed via spark plasma sintering for high-temperature/strength applications. JMEPEG 32, 18–28 (2023).

Tsai, M.-H. & Yeh, J.-W. High-entropy alloys: A critical review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2(3), 107 (2014).

Cao, B. X., Wang, C., Yang, T. & Liu, C. T. Cocktail effects in understanding the stability and properties of face-centered-cubic high-entropy alloys at ambient and cryogenic temperatures. Scripta Mater. 187, 250–255 (2020).

Naseri, M. et al. Enhancing the mechanical properties of high-entropy alloys through severe plastic deformation: A review. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 5, 100054 (2024).

Zhou, J.-L. et al. Research status of tribological properties optimization of high-entropy alloys: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 58, 4257–4291 (2023).

Manzoni, A. M. & Glatzel, U. New multiphase compositionally complex alloys driven by the high entropy alloy approach. Mater. Charact. 147, 512–532 (2019).

Shivam, V. et al. A novel Fe-rich non-equiatomic medium-entropy alloy with superior mechanical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 952, 170029 (2023).

Yu, G. et al. Dzherenova Ti-rich carboborides in the multi-component high-boron alloy: Morphology and elemental distribution. Phys. Chem. Solid State 24, 707–713 (2023).

Oses, C., Toher, C. & Curtarolo, S. High-entropy ceramics. Nat. Rev Mater 5, 295–309 (2020).

Moon, J. et al. A new strategy for designing immiscible medium-entropy alloys with excellent tensile properties. Acta Mater. 193, 71–82 (2020).

Mceldowney, D., Tamirisakandala, S. & Miracle, D. B. Heat-treatment effects on the microstructure and tensile properties of powder metallurgy Ti-6Al-4V alloys modified with boron. Metall. Mater. Transact. A. 41A, 1003–1015 (2010).

Srinivasan, R., Miracle, D. & Tamirisakandala, S. Direct rolling of as-cast Ti-6Al-4V modified with trace additions of boron. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 487, 541–551 (2008).

Yu, Y., Li, H., Mi, X., Gao, Q. Effect of TiB on nucleation and growth up of α phase in Ti-6Al-4V-0.1B alloy, Mater. Sci. Forum, (2017)

Rossi, M. C. et al. Effect of alloying elements on laser surface modification of powder metallurgy to improve surface mechanical properties of beta titanium alloys for biomedical application. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 14, 1222–1234 (2021).

Pitchi, C. S., Priyadarshini, A., Sana, G. & Narala, G. S. K. R. A review on alloy composition and synthesis of β-Titanium alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Proc. 26, 3297–3304 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Compressive properties and microstructure evolution in NiTiNb alloy with mesh eutectic phase. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 801, 140434 (2021).

Sak, A. et al. Influence of polyetheretherketone coatings on the Ti-13Nb-13Zr titanium alloy’s bio-tribological properties and corrosion resistance. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 63, 52–61 (2016).

Louzguina-Luzgina, L. V., Louzguine-Luzgin, D. V. & Inoue, A. Effect of B addition to hypereutectic Ti-based alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 474, 131–133 (2009).

Khorasani, A. M., Goldberg, M., Doeven, E. H. & Littlefair, G. Titanium in biomedical applications—properties and fabrication: A review. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 5, 593–619 (2015).

Fellah, M. et al. Microstructural and photocatalytic properties of nanostructured near-β Ti-Nb-Zr alloy for total hip prosthesis use. Kuwait J. Sci. 51, 100276 (2024).

Arias-González, F. et al. In-situ laser directed energy deposition of biomedical Ti-Nb and Ti-Zr-Nb alloys from elemental powders. Metals 11, 1205 (2021).

Ozerov, M. et al. Effect of cold rolling on microstructure and mechanical properties of a cast TiNbZr-based composite reinforced with borides. Metals 14, 104 (2024).

Ozerov, M. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of medium-entropy TiNbZr alloy-based composites, reinforced with boride particles. J. Alloys Compd. 938, 168512 (2023).

Ma, N. et al. Research progress of titanium-based high entropy alloy: Methods properties, and applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 603522 (2020).

Kaya, M., Yakuphanoğlu, F., Elibol, E., Köm, M. Microstructure characterization and biocompatibility behaviour of TiNbZr alloy fabricated by powder metallurgy, Mater. Res. Express, (2019).

Meng, Q., Liu, Q., Guo, S., Zhu, Y. & Zhao, X. Effect of thermo-mechanical treatment on mechanical and elastic properties of Ti–36Nb–5Zr alloy. Prog. Nat. Sci.: Mater. Int. 25, 229–235 (2015).

Singh, G. & Ramamurty, U. Boron modified titanium alloys. Progress Mater. Sci. 111, 1006 (2020).

Murray, J. L. Liao, P. K., Spear, K. E. The B-Ti (boron-titanium) system, Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr, 7(6) (1986).

Sola, A. & Trinchi, A. Boron-induced microstructural manipulation of titanium and titanium alloys in additive manufacturing. Virt. Phys. Prototyp. 18(1), e2230467 (2023).

Arun, S. & Radhika, N. Bassiouny saleh, advances in vacuum arc melting for high entropy alloys: A review. Vacuum 226, 113314 (2024).

H. Czichos, T. Saito, Leslie Smith (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Materials Measurement Methods. E-ISBN: 3-540-30300-6. Page 107.

Takeuchi, A. Inoue, Classification of bulk metallic glasses by atomic size difference, heat of mixing and period of constituent elements and its application to characterization of the main alloying element. Mater. Trans. 46, 2817–2829 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y. J., Lin, J. P., Chen, G. L. & Liaw, P. K. Solid-solution phase formation rules for multi-component alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 534–538 (2008).

Mizutani, U., The Hume-Rothery rules for structurally complex alloy phases Surface properties and engineering of complex intermetallics. World Sci., 323–99 (2010).

Wang, Z., Qiu, W., Yang, Y. & Liu, C. T. Atomic-size and lattice-distortion effects in newly developed high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements. Intermetallics 64, 63–69 (2015).

Takeuchi, A. & Inoue, A. Calculations of mixing enthalpy and mismatch entropy for ternary amorphous alloys. Mater. Trans. 41, 1372 (2000).

Tian, F., Varga, L. K., Chen, N., Shen, J. & Vitos, L. Empirical design of single phase high-entropy alloys with high hardness. Intermetallics 58, 1–6 (2015).

Pogrebnjak, A. A., Bagdasaryan, I. & Yakushchenko, V. M. Beresnev, The structure and properties of high-entropy alloys and nitride coatings based on them. Russ. Chem. Rev. 83, 1027 (2014).

Guo, S., Ng, C., Lu, J. & Liu, C. T. Effect of valence electron concentration on stability of fcc or bcc phase in high entropy alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 109(10), 103505 (2011).

Lee, S-H., Ashfia, H., Wenge, Y., Jaeyong, K., Physica B Detail: 551, 33 (2018) Authors:

Lei, H. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CrFeNiBx eutectic high entropy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 887, 145741 (2023).

Guo, S. & Sun, H. Superhardness induced by grain boundary vertical sliding in (001)-textured ZrB2 and TiB2 nano films. Acta Materialia 218, 117212 (2021).

Ivashchenko, V. I., Turchi, P. E. A., Shevchenko, V. I. & Mediukh, N. R. Leonid Gorb, Jerzy Leszczynski, Phase diagram, electronic, mechanical and thermodynamic properties of TiB2–ZrB2 solid solutions: A first-principles study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 263, 124340 (2021).

Bermingham, M. J., McDonald, S. D., Nogita, K., St John, D. H. & Dargush, M. S. Effects of boron on microstructure in cast titanium alloys. Scr Mater. 59, 538–541 (2008).

Chandravanshi, V. K., Sarkar, R., Ghosal, P., Kamat, S. V. & Nandy, T. K. Effect of minor additions of boron on microstructure and mechanical properties of as-cast near titanium alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 41, 936–946 (2010).

Shao, L. et al. β-Ti alloys for orthopedic and dental applications: A review of progress on improvement of properties through surface modification. Coatings 11, 1446 (2021).

Pederson, R., Gaddam, R. & Antti, M.-L. Microstructure and mechanical behavior of cast Ti-6Al-4V with addition of boron. Cent. Eur. J. Eng. 2, 347–357 (2012).

Okulov, I. V. et al. Open porous dealloying-based biomaterials as a novel biomaterial platform. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 88, 95–103 (2018).

Kato, K. Wear in relation to friction–a review. Wear 241, 151–157 (2000).

Mohamed, L. Z., Elsayed, A. H., Elkady, O. A. & Abolkassem, S. A. physico-mechanical, microstructure, and chemical properties of Si/Ti/Nb additions to CoCrMoW medium entropy alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24(3), 9897–9914 (2023).

Liang, S. Review of the design of titanium alloys with low elastic modulus as implant materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 22, 2000555 (2020).

Luo, D. et al. Tribological behavior of high entropy alloy coatings: A review. Coatings 12, 1428 (2022).

Senkov, O. N., Rao, S., Chaput, K. J. & Woodward, C. Compositional effect on microstructure and properties of NbTiZr-based complex concentrated alloys. Acta Mater. 151, 201–215 (2018).

Nihara, K., Morena, R. & Hasselman, D. P. H. Evaluation of 1Kic of brittle solids by the indentation method with low crack-to-indent ratios. J. Mater. Sci. Letters. 1, 13 (1982).

Shadangi, Y., Shivam, V., Chattopadhyay, K. & Mukhopadhyay, N. K. Powder metallurgical processing of Sn-reinforced Al-Cu-Fe quasicrystals: Structure, microstructure and toughening behavior. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 6, 60 (2022).

Köster, U., Liebertz, H. & Liu, W. Plastic deformation of quasi-crystalline and crystalline phases in AlCuFe alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 181–182, 777 (1994).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Mohamed Eissa from CMRDI for his kind help during the preparation of the cast samples.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E. Managed preparation of cast samples; M.A. and L.Z.M. samples characterization and wear tests. H.S. Transmission Micrographs; S.E. and L.Z.M. wrote the manuscript and H.M. general supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alshafey, M., Megahed, H., El-Hadad, S. et al. Characteristics of cast Ti53.3-xNb10Zr10Ni10Co10Fe6.7Bx compositionally complex alloys. Sci Rep 14, 29713 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78854-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78854-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Characterization of TiCrMoZr (Nb/Mn) Complex Concentrated Alloys Synthesized by Vacuum Arc Melting

International Journal of Metalcasting (2025)

-

Characterization and Evaluation of Ti-12Mo-3Ag Alloy Fabricated for Biomedical Applications by Powder Metallurgy

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)