Abstract

The present study was designed to identify the preoperative clinical and imaging findings influencing adverse clinical outcomes in patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis after pericardiectomy. Patients with constrictive pericarditis who underwent pericardiectomy between January 2009 and September 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Preoperative evaluations included assessments of clinical symptoms, comorbidities, laboratory tests, cardiac computed tomography (CT), and transthoracic echocardiography. The volume of pericardial calcifications was quantified on calcium scoring CT. Adverse clinical events were defined as cardiovascular death or hospitalization due to cardiac causes, and all-cause mortality was assessed. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard model analysis were performed to find factors associated with adverse clinical events. Among the 91 patients with available preoperative CT scans, 26 (28.6%) experienced adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy, with 19 (20.9%) experiencing cardiovascular deaths. On multivariable Cox analysis, larger pericardial calcium volume hazard ratio [HR], 1.004 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.001–1.006) per 1cm3 increase; p = 0.005), higher E/E’ ratio (HR, 1.059, 95% CI, 1.015–1.105, p = 0.008), and lower albumin level (HR, 0.476, 95% CI, 0.229–0.986, p = 0.046) were significant factors associated with the adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy. The amount of pericardial calcification could be associated with the efficacy of pericardiectomy and potentially have implications for postoperative outcomes. Additionally, a high E/E ratio on echocardiography is indicative of unfavorable postoperative prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis (CP) manifests as pericardial thickening and calcification, leading to constrictive physiology and heart failure symptoms. CP can be diagnosed by various imaging methods1,2,3,4, with Mayo Clinic echocardiographic criteria used to diagnose constrictive physiology. These echocardiographic criteria include respiration-related ventricular septal shift (septal bouncing), preserved or increased medial mitral e’ velocity ≥ 9 cm/s, and prominent hepatic vein expiratory diastolic flow reversal. As a complementary tool, pericardial thickness and the extent of pericardial calcifications can be evaluated by computed tomography (CT)3,4.

Pericardiectomy is effective in the treatment of chronic CP. Patients with idiopathic CP have a better prognosis than patients with CP caused by other factors1,2,5, with extended or radical pericardiectomy resulting in better outcomes than subtotal pericardiectomy6,7,8. Despite shifts in surgical approaches, however, few recent studies to date have evaluated the preoperative factors that affect postoperative outcomes9,10,11,12.

Pericardial calcification on chest radiography was reported to be a risk factor for poor outcome after pericardiectomy2,6. Surgery could be challenging in patients with thick or extensive pericardial calcification, suggesting that calcification can affect the relative efficacy of surgery in these patients. A recent study reported, however, that CP patients with a lower degree of calcification and a dominance of fibrosis had poorer outcomes after pericardiectomy12. That study had an important limitation, as it did not exclude patients with tumorous conditions involving the pericardium, which could have influenced outcomes, especially cancer-related deaths. Furthermore, in patients with tumor invasion, it may be challenging to accurately assess the extent of pericardial calcification, and the attenuation of the tumor may be evaluated as having a fibrotic component. Therefore, we excluded those patients with tumor invasion, and the aims of this study were to determine whether preoperative clinical, echocardiography, and cardiac CT findings including quantitative amount of pericardial calcification in patients with chronic CP are associated with clinical outcomes after pericardiectomy.

Results

Patients

Of the 91 patients analyzed, 26 (28.6%) had 5-year adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy. Postoperative echocardiography showed that 11 patients still exhibited all four classic features of constriction—septal bowing, IVC plethora, increased medial mitral e’ velocity ≥ 9 cm/s, and prominent hepatic vein expiratory diastolic flow reversal—without improvement. In this group, adverse events were significantly more common (7 [63.6%] vs. 19 [23.8%], p = 0.011), and there was a significantly higher incidence of cardiovascular death (6 [54.5%] vs. 13 [16.2%], p = 0.009). Among these 11 patients, 6 experienced cardiac-related death, and 1 was hospitalized for heart failure, leading to 7 patients being included in the adverse events group. The remaining 4 patients managed their symptoms with medical management and are being followed up in outpatient care. In contrast, among the 80 patients who showed improvement in at least one echocardiographic feature, 13 died due to postoperative complications such as stroke, heart failure, or infective endocarditis, and 6 were hospitalized for heart failure or arrhythmia. In total, 26 patients—19 cardiovascular deaths and 7 rehospitalizations—were classified into the adverse events group.

The median follow-up duration was 4.23 years (IQR, 2.04–7.78). The mean ± standard deviation age of patients at pericardiectomy was 58.2 ± 9.7 years, with 66 (72.5%) patients being men. The main etiology was idiopathic (n = 49, 53.8%), followed by tuberculosis (26.4%). The 5- and 10-year overall survival rates in the patient cohort were 81.0 ± 4.6% and 72.4 ± 6.2%, respectively, whereas the 5- and 10-year event-free survival rates were 67.8 ± 5.4% and 64.9 ± 5.9%, respectively.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire patient population, as well as their comparison in groups of patients with and without adverse clinical events. The demographic characteristics and comorbidity rates did not differ significantly in these two groups. Patients with adverse events presented lower hemoglobin (mean, 11.2 vs. 12.1 g/dL, p = 0.003) and albumin (median, 3.2 vs. 3.5 g/dL, p = 0.017) level compared to those without adverse events. Five-year mortality (50.0 vs. 6.2%, p < 0.001) and overall mortality (56.0 vs. 7.6%, p < 0.001) significantly differ between two groups.

Preoperative imaging

CT findings in the two patient groups did not differ significantly, as determined by the presence of pericardial calcification, pericardial calcium volume or score (Table 2). However, maximal pericardial calcification thickness at LV was thicker in patients with adverse clinical events compared to those without adverse clinical events (median, 2.6 vs. 0.0 mm, p = 0.029). The percentages of patients who underwent pericardiectomy alone or concomitant surgery involving valves or coronary procedures also did not differ in these two groups.

Preoperative echocardiography showed that E/E’ ratio (10.0 vs. 7.0, p = 0.016) were significantly larger in patients with adverse clinical events than in patients without adverse clinical events (Supplemental Table 1). After pericardiectomy, echocardiographic parameters were not significantly differed between the two groups.

Predictors of adverse clinical events

Univariable Cox regression analyses revealed that the presence of significant coronary artery disease (moderate to severe stenosis), lower hemoglobin and albumin concentrations, higher blood urea nitrogen concentrations, larger pericardial calcium volume and score, thick maximal pericardial calcification thickness at LV side, lower LVEF, and higher E/E’ ratio on preoperative echocardiography were factors associated with adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy (all, p < 0.05) (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 2). The optimal cut-off value of pericardial calcification volume and score associated with adverse clinical events were determined to be 44,939 mm3 and 54,537, respectively. The pericardial calcium volume, considering multicollinearity, was analyzed in the multivariable model, excluding the pericardial calcium score or thickness. Preoperative E/E’ ratio of ≥ 11 was selected as a clinical cut-off value for further analysis. The cut-off value for BNP was 323 pg/mL, and BNP of ≥ 323 pg/mL (HR, 2.506; 95% CI 1.158–5.424; p = 0.020) was a significant factor on univariable Cox regression analysis.

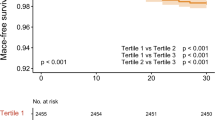

A multivariable Cox proportional hazard model with backward elimination method showed that lower albumin level (HR, 0.476; 95% CI, 0.229–0.986; p = 0.046), larger pericardial calcium volume (HR, 1.004, 95% CI 1.001–1.006; p = 0.005) and higher E/E’ ratio (HR,1.059; 95% CI, 1.015–1.105; p = 0.008) were independent predictors of adverse clinical events. With the use of binary parameters using the cut-off values, lower albumin level (HR, 0.406; 95% CI, 0.196–0.844; p = 0.016), larger pericardial calcium volume of ≥ 44939 mm3 (HR, 2.654, 95% CI, 1.018–6.917; p = 0.046) and E/E’ ratio of ≥ 11 (HR, 2.474; 95% CI, 1.064–5.751; p = 0.035) were selected as independent predictors. Upon dividing the patients into two groups based on the pericardial calcium amount using the threshold of 44939 mm3, the larger pericardial calcium group exhibited poorer outcomes in terms of event-free survival (p = 0.031) and overall survival (p = 0.036) (Fig. 1). The group with an E/E’ ratio of ≥ 11 demonstrated a significant difference in event-free survival compared to the group with an E/E’ ratio < 11 (p = 0.005).

Discussion

In this study, preoperative clinical and imaging findings in patients with CP were compared to identify factors predicting postoperative adverse clinical events. Factors predicting the occurrence of adverse clinical events included lower albumin level, larger pericardial calcification volume, and a higher E/E’ ratio.

In our study, lower albumin levels were found to be significantly associated with worse clinical outcomes following pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis. Hypoalbuminemia, indicative of poor nutritional status and systemic inflammation, may reflect an underlying chronic illness that compromises recovery and increases the risk of postoperative complications12,13. These insights underscore the importance of addressing nutritional status in the perioperative management of these patients.

Previously, pericardial calcification on chest radiography was found to be a risk factor for poor outcome after pericardiectomy2,6, although the extent of calcification on other imaging modalities, such as CT, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, was found to be unrelated to clinical outcomes1,10,14,15,16. However, only one study performed quantification of pericardial calcifications, with a design similar to that of the present study, and attempted to determine the relationship between pericardial calcification and mid-term outcomes, including 5-year hospitalization events12. However, that study, which found that mid-term outcomes were poorer in patients with low pericardial calcium, was limited due to its inclusion of seven patients with malignant causes of CP. Pericardial thickening due to malignant causes is not related to typical patterns of pericardial calcification but rather to tumor invasion, indicating that these results were affected by tumor-associated progression and mortality. Most malignant cases in that study were in the lower calcium score group, potentially biasing the results. Indeed, clinical events occurred in five of the seven patients with malignant causes of CP, with the frequency of clinical events being significantly greater in patients with malignant than non-malignant CP (71.4% [5/7] vs. 22.0% [20/91], p = 0.004). Moreover, in the previous study, pericardial calcium was reported as mean ± standard deviation, however reflecting a non-normal distribution that should have been presented as a median. For comparison, we calculated calcium volume in our study as mean ± standard deviation and found higher mean values (5066 ± 10,677 vs. 16,810 ± 25,335 in the previous study, and 69,659 ± 159,818 vs. 19,827 ± 64,196 in our study, in the groups with adverse events and no adverse events, respectively). This suggests that the previous study population may have had less severe calcification.

The present study eliminated the impact of malignancy on patient outcomes by excluding patients with CP combined tumor invasion. The amount of pericardial calcification was independently associated with the adverse clinical outcomes after pericardiectomy. Especially, the group of patients who experienced adverse events after pericardiectomy had significantly thicker pericardial calcification on the LV side compared to those without adverse events. Surgery may be challenging in patients with abundant pericardial calcification on the LV side due to the posterior location, compared to the RV side. Incomplete pericardiectomy, where calcified tissue is not fully decorticated, may result in the persistence of constrictive physiology {Chowdhury, 2006 #39}. This incomplete resolution can prevent the restoration of LV function, which plays the most critical role in cardiac output, potentially leading to adverse events post-pericardiectomy.

Previously, patients with idiopathic causes of CP have been reported to be shown the best prognosis after pericardiectomy1,15. However, in the present study, idiopathic causes of CP did not significantly affect event-free survival. The 5-year overall survival rate after pericardiectomy (80.95%) in this study was within previously reported ranges of 64–85.8%15,17,18,19,20,21. Factors such as prior radiation history, older age, impaired renal and hepatic function, advanced NYHA functional class, elevated pulmonary artery pressure, high medial e’ velocity and significant tricuspid regurgitation are recognized as indicators associated with unfavorable outcomes after pericardiectomy5,9,11,22,23. The different discovery of these various factors in each study may be influenced by variations in patient cohorts. Furthermore, a shift in surgical practices, from considering subtotal pericardiectomy sufficient in the past to a more proactive and extensive removal of the pericardium, especially after the recognition that total pericardiectomy is more effective, could contribute to these differences6,7,8. Further research on factors influencing the outcomes of pericardiectomy, including attempts to quantify pericardial calcification, is necessary in large cohorts.

This study had several limitations, including its retrospective, single-center design. By focusing on patients who underwent pericardiectomy, this study did not include patients ineligible for surgery, potentially introducing a selection bias. Additionally, if pericardiectomy alone was deemed insufficient in resolving CP, patients underwent other, concurrent, operations such as valvular surgery. Although this may have affected the results of this study, univariable Cox regression analysis found that concurrent surgery did not significantly affect adverse clinical events. Moreover, pericardiectomy could be influenced by surgeon-associated factors, and the extent of pericardiectomy might be insufficient case by case even though surgeons designated to perform extended pericardiectomy. Also, the lack of impact of preoperative symptom severity, comorbidities, and etiology of pericarditis on event rates in our study may be explained by the stronger influence of structural factors, such as calcification, on surgical outcomes. While the small sample size in the high calcium volume group (n = 11) and the variability of the cut-off value across cohorts limit the generalizability of our findings, this example highlights that extensive calcification can be associated with poor prognosis, potentially leading to adverse outcomes even after pericardiectomy. Especially, multivariable Cox analysis revealed a significant association between the continuous value of pericardial calcium volume and adverse events, with a 1.004-fold increase in risk per 1 cm³, implying a 1.5-fold increase in risk for approximately 100 cm³ of calcification. Finally, cardiovascular events can be confused with other causes rather than heart failure. Because heart failure is difficult to diagnose clinically, events were determined by evaluating laboratory and imaging results, along with patient symptoms.

The present study found that larger amount of pericardial calcification in chronic CP may affect the adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy. Preoperative factors, such as albumin levels and the E/E’ ratio on echocardiography, were identified as related to postoperative outcomes. These results suggest the need for further confirmation in larger patient cohorts.

Methods

Patient cohort

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center in South Korea. The Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center in South Korea waived the need for informed consent. All procedures and study contents adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The electronic medical records of our center were reviewed retrospectively to identify patients with CP who underwent pericardiectomy between January 2009 and September 2023. Patients diagnosed with mediastinal tumor with pericardial invasion, acute pericarditis, and underlying congenital heart disease, as well as patients who underwent a second operation after initial pericardiectomy, were excluded (Fig. 2). Extended (total) pericardiectomy is performed as a principle, and a median sternotomy is carried out. One patient undergoing a thoracotomy approach was excluded due to the difference in surgical procedure. Finally, 91 patients with preoperative cardiac CT scans were included. Preoperative characteristics of these patients were evaluated, including New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and the results of routine laboratory testing, electrocardiography, cardiac CT, and transthoracic echocardiography.

Clinical events

Adverse clinical events were defined as cardiovascular causes of hospitalization and/or death after pericardiectomy. Cardiovascular-related hospitalization was defined as hospitalization due to CP or heart failure symptoms, with chief complaints of dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain, tachycardia, and edema. Cardiovascular mortality and overall mortality were assessed from the National Health Insurance Database.

Surgery

Pericardiectomy was performed by four expert cardiac surgeons. All patients were planned to undergo extended pericardiectomy through a median sternotomy approach; however, the ultimate extent of pericardiectomy depended on each patient’s condition and the discretion of the surgeons. For instance, if intraoperative assessment revealed difficulty in dissection due to severe pericardial adhesions, or if there was a devastating injury during extensive pericardiectomy or a risk of potential injury associated with the dissection, the surgeon made the decision to proceed with partial pericardiectomy. Extended pericardiectomy included the removal of the entire pericardium from both the anterior and posterior aspects of the heart, including the diaphragmatic pericardium (cardiac base) and the pulmonary vein level. To avoid phrenic nerve palsy, pericardiectomy was performed with being preserved the longitudinal segment through which both phrenic nerves pass. The decision to use cardiopulmonary bypass was made intraoperatively.

Imaging protocol

All patients underwent enhanced cardiac CT scans (Somatom Force or Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), with retrospective electrocardiogram gating and electrocardiogram (ECG)-based tube current modulations. Coronary calcium scoring CT was performed at 120 kVp, with a tube current of 80 mA, and was obtained by prospective ECG-gated acquisition at 70% or 35% of the R-R interval, depending on the heart rate. A bolus of 50–120 cc of non-ionic CT contrast agents was injected at a rate of 4–7 cc/sec using a power injector. CT scans were performed using a bolus tracking method, with a gantry rotation time ≤ 350 ms.

Echocardiography was performed using commercially available ultrasound machines with 3–5 MHz real-time transducers (iE33, EPIC; Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA; Vivid 7, E9, General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA). Conventional two-dimensional and Doppler images were obtained by expert cardiologists according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations17. Parameters recorded included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular (LV) dimensions, left atrial diameter, mitral flow velocity, and the early diastolic velocities of the medial and lateral mitral annuli.

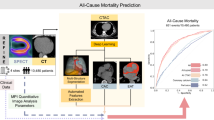

Image analysis

Calcium scoring CT images before pericardiectomy were analyzed using a commercial software to determine pericardial calcium volume and score, based on the Agatston score system (Syngo.via) (Fig. 3). Characteristics of pericardial thickening, including the presence of pericardial calcification, quantified volume and score of pericardial calcium, maximum pericardial thickness, maximum pericardial calcium thickness, and the presence of pericardial calcification adjacent to the major coronary arteries were evaluated on a PACS station. The presence of pericardial or pleural effusion was also recorded.

Quantification of pericardial calcium amount using the Agatston score method. (A) Cardiac gated calcium scoring image of the heart. (B) Pericardial calcium (orange color) selected by the software. (C) Three-dimensional volume rendering image of the heart indicating the extent of pericardial calcifications. (D) Results of quantified volume and score of pericardial calcium.

Statistics

Continuous variables are expressed as means ± standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, with the normality of their distribution evaluated using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Normally distributed continuous variables in groups of patients with and without adverse clinical events after pericardiectomy were compared using Student’s t-tests, with non-normally distributed variables compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were compared using the chi square test or Fisher’s exact test.

The maximal selected log-rank statistics, calculated using the maxstat R package, were used to determine the optimal cut-off for continuous variables such as BNP, preoperative pericardial calcification volume and score, and E/E’ ratio. Using this method, continuous values were converted into categorical variables based on the threshold value, with the latter used to predict adverse clinical events. Factors predicting adverse clinical events were analyzed by Cox proportional hazard models. Variables with a p-value < 0.20 on univariable Cox regression analysis were selected as candidates for multivariate Cox regression analysis. Variables with P > 0.05 were removed using a backward elimination method. For parameters deemed significant through multivariable Cox regression analysis, Kaplan-Meier analysis was conducted to assess event-free survival and overall survival. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 and R version 4.3.2.

Data availability

Data are available from the Asan Medical Center Institutional Data Access/Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Requests for data access can be sent to the corresponding author at radkoo@amc.seoul.kr.

Abbreviations

- CP:

-

constrictive pericarditis

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- ECG:

-

electrocardiogram

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- LV:

-

left ventricular

- LVEF:

-

left ventricular ejection fraction

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

References

Bertog, S. C. et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 1445–1452 (2004).

Ling, L. H. et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 100, 1380–1386 (1999).

Miranda, W. R. & Oh, J. K. Constrictive pericarditis: a practical Clinical Approach. Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 59, 369–379 (2017).

Welch, T. D. Constrictive pericarditis: diagnosis, management and clinical outcomes. Heart. 104, 725–731 (2018).

Murashita, T. et al. Experience with pericardiectomy for constrictive Pericarditis over eight decades. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 104, 742–750 (2017).

Chowdhury, U. K. et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic evaluation of two surgical techniques. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 81, 522–529 (2006).

Choi, M. S. et al. Long-term results of radical pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis in Korean population. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 14, 32 (2019).

Nozohoor, S., Johansson, M., Koul, B. & Cunha-Goncalves, D. Radical pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis. J. Card Surg. 33, 301–307 (2018).

Nishimura, S. et al. Long-term clinical outcomes and prognostic factors after Pericardiectomy for Constrictive Pericarditis in a Japanese Population. Circ. J. 81, 206–212 (2017).

Senapati, A. et al. Disparity in spatial distribution of pericardial calcifications in constrictive pericarditis. Open. Heart. 5, e000835 (2018).

Yang, J. H. et al. Prognostic importance of mitral e’ velocity in constrictive pericarditis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 22, 357–364 (2021).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Pattern of pericardial calcification determines mid-term postoperative outcomes after pericardiectomy in chronic constrictive pericarditis. Int. J. Cardiol. 387, 131133 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. Surg. Today. 53, 861–872 (2023).

George, T. J. et al. Contemporary etiologies, risk factors, and outcomes after pericardiectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 94, 445–451 (2012).

Kang, S. H. et al. Prognostic predictors in pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 147, 598–605 (2014).

Yangni-Angate, K. H. et al. Surgical experience on chronic constrictive pericarditis in African setting: review of 35 years’ experience in Cote d’Ivoire. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 6, S13–s19 (2016).

Tirilomis, T., Unverdorben, S. & von der Emde, J. Pericardectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis: risks and outcome. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 8, 487–492 (1994).

Arsan, S. et al. Long-term experience with pericardiectomy: analysis of 105 consecutive patients. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 42, 340–344 (1994).

DeValeria, P. A. et al. Current indications, risks, and outcome after pericardiectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 52, 219–224 (1991).

Seifert, F. C. et al. Surgical treatment of constrictive pericarditis: analysis of outcome and diagnostic error. Circulation. 72, Ii264–Ii273 (1985).

Bozbuga, N. et al. Pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive tuberculous pericarditis: risks and predictors of survival. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 30, 180–185 (2003).

Adler, Y. et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of Pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 36, 2921–2964 (2015).

Komoda, T., Frumkin, A., Knosalla, C. & Hetzer, R. Child-pugh score predicts survival after radical pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 96, 1679–1685 (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00218630 and No. 2022R1A5A1022977).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K, H.S.L., and H.J.K wrote the main manuscript. H.S.L., H.J.K and Y.A. contributed to data analysis and concept of design. D.K. D.H.Y. and J.K. approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to data collection and analysis and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center. Patients’ informed consent was waived due to retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B., Lee, H.S., Ahn, Y. et al. Impact of preoperative clinical and imaging factors on post-pericardiectomy outcomes in chronic constrictive pericarditis patients. Sci Rep 14, 28145 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78923-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78923-0