Abstract

Renewable energies are interesting as an alternative and sustainable resource for air conditioning applications. But initial investment cost of equipment, whose employed for converting the renewable energy into usable shape and also for air conditioning duty, are significant. Therefore, determining the optimum sizing has high priority. In current study, water cooled vapor compression refrigeration cycle powered by wind energy and storage tank is proposed, simulated and optimized. To contribute the total effective aspects in system optimum size, the thermo-economic-environmental criteria is defined. By the help of databank of parametric analysis, the optimum design variables are determined by employing the GA optimization algorithm. In the following, an intelligence neural network is developed to learn the reliable correlation between the inputs and outputs data. Finally, the optimum size of each subsystem is determined by using triple-objective MPSO. Based on detailed economic analysis, the system payback period is estimated about 450 days which is 41% less than the conventional system. The daily COP and exergy efficiency of the whole system has improved up to 98% and 40%, after substituting the optimum design variable parameters. Triple-objective MPSO results show that, the ice storage tank should be selected 22% smaller than the initial amount.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the Statistical Review of World Energy (BP 2019), increasing of \({\text{CO}}_{{2}}\) emission rate is equal to 2% which be a high value for seven years and can show the growth of fossil fuels consumption in recent years1. To reduce that, two approaches could be taken as: the efficient energy conversion (by optimizing the system’s operation2) and the use of renewable energies3. In this way, the net-zero energy systems are widely noticed4. In the global low-carbon economy context, the most commercialized prospect of renewable energies is wind power due to its mature technology, wide global distribution, flexible installation, the threat of zero carbon footprints etc.5,6.

Compression Chillers are widely used in residential and industry applications with consuming a lot of electricity. In windy regions, Wind Turbine (WT) can suitably substitute for grid electricity. Due to instability of wind energy, a storage device should be employed to sustainable access of wind products7. Therefore, a Wind-Powered Water-cooled Vapor Compression Refrigeration (VCR) cycle with a Storage tank system (WPWVCRS) is proposed in the present study. The combined system includes three subsystems namely the cold production (VCR with VSC integrated with WCT), the storage and distribution (IST and AHU) and the power generation subsystem (WT). Detailed performance of added equipment (e.g., WCT, VSC and AHU) are accurately assessed compared to previous study8. Based on the two above mentioned approaches to reduce the penalty cost of pollutants production, this study’s main focus is on the thermo-economic-environmental analysis of WPWVCRS and its component’s optimizing and sizing. In this regard, the literature review includes optimizing procedure of the main components constituting the three subsystems introduced in the combined system.

In optimization concept, metaheuristic tools were extensively applied in the previous literature9. Moreover, the data collected approaches had attached more attention separately based on machine learning especially neural network methods10,11 or combined with other optimization algorithms which played a key role in the computational time11,12. VCRs are widely used to supply refrigeration demand in various applications with consuming about 15% of electricity in building sector and produce about ∼10% of greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, VCR performance optimization seems necessary13. One of the oldest efforts to estimate simple VCR performance and cost was carried out by Otaibi et al.14. The reduction of \({\text{CO}}_{{2}}\) emission, its cost and energy-saving amount have been determined based on optimum mass flow rate by using a parametric thermo-economic and environmental optimization15. Various optimization methods have been employed to evaluate and optimize the VCR performance such as Taguchi and ANOVA16, Beyer’s method combined with Artificial Neural Network (ANN)17. Kong et al.18 applied a self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm to minimize the VCR energy consumption. Developing a nonlinear mathematical formulation combined with a modified Genetic Algorithm (GA) was carried out by focusing on all system components and interactions between them19. Zhao et al.20 established a decentralized optimization method to obtain the Pareto optimum solution for VCR. In another study, a multi-objective optimization procedure was performed from thermodynamic, economic and environmental viewpoints for cascade VCR cycles by using GA with the TOPSIS decision-making method21,22. Sayyadi and Nejatolahi23 optimized VCR assisted with WCT based on three optimization approaches (single and multi-objective optimizations) by employing GA. In multi-objective optimization problems, the weight function method can reduce the various objective functions number to one number. The weight function amounts dependent on each variable’s effectiveness on objective function’s value24. In this regard, a multi-objective GA optimization procedure was performed by EES software capabilities for a combined VCR25. Zhar et al.26 conducted a parametric study for combined VCR based on the energy-levelized cost as objective functions. Salim and Kim27 analyzed and optimized the same system with a multi-objective non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGAII). Another statistical technique such as TOPSIS based on entropy weight criteria was applied to optimize the combined VCR28. Nonlinear programming (NLP) based on the conjugated direction method29 was another optimization tool to evaluate the combined VCR cycle performance.

The IST is an effective device which can be filled the gap between supply and demand of refrigeration30. Investigating and optimizing the cooling systems integrated with IST and WCT by two approaches has been take into account in the literature13,31. In the first one, a packaged unit (chiller) was considered at which the optimal performance for the chiller was targeted based on IST size relation and using the control strategy method32 by energy savings as high as 9.4% and electricity cost savings up to 30%13. In Chen et al.’s study33 an integrated air conditioning system including a screw chiller, IST and auxiliary equipment were optimized for the chiller and IST capacities based on the total system costs. Song et al.34 presented electric tariff and ice storage rate effects on the chiller capacity and system total cost under three control strategies for four building kinds. Also, managing the charge and discharge process concluded 11.3% and 9.3% of electricity cost-saving amounts per day and month by employing optimal strategy35. But in the second category, the governing equations on the different equipment behavior (e.g., compressor, evaporator and condenser, expansion valve and the additional equipment WCT and IST), were separately considered36. Badar et al.37 optimized the sensible heat storage device based on the thermodynamic second-law criteria. Meanwhile, as a result of Ezan et al.38, the energy and exergy efficiencies simultaneously had important effects on IST performance. Sanaye and Shirazi39 investigated the effects of the on-peak and off-peak different costs of grid electricity on the performance of the VCR cycle integrated with an IST and WCT by using GA algorithm. Also, by switching the electricity consumption from on-peak to off-peak times reached to 13.45% and 32.65% reductions of electricity consumption for partial and full loads methods40. Habeebullah41 compared the full storage with the partial technique in the ice storage cooling system and optimized its performance based on the cost criteria. As his result, the full storage strategy had less electricity consumption. A multi-objective GA was used to improve the annual benefit and exergy efficiency of the proposed combined system by Sanaye and Khakpey42. They reported saving money equal to (1.35×105 [$/year] (61.5%) from electricity grid consumption. In another study, Shirazi et al.43 reported 3.59% and 11.63% growth in the exergetic efficiency and output power, respectively.

The wind instability is one of the optimization constraints for the energy produced by WT44. The mixed-integer linear programming was established to minimize the solar and wind curtailments45. The optimization procedures could be focused on the energy storage benefits and the system cost-effectiveness in thermodynamic systems integrated with wind energy storage devices3. The reduction by about 10% and 20.4% for two objective functions namely the levelized cost of energy and electricity supply reliability were reported by Yang et al.46. Enhancements in the benefits and lifetime energy storage system up to 327.69% and 62.89% were reached by using PSO optimization algorithm5. Moreover, PSO algorithm was employed by Lorestani and Ardehali47 to optimize the wind-photovoltaic-thermal storage system’s total cost and also by Soheily et al.48 to determine the optimum size of each equipment of their proposed system. Two study have been found in which thermo-economic and thermo-environmental assessment was done for evaluating and optimizing wind-powered thermodynamic systems. This is important from the point of view that was chosen in present study. The first one carried out by Ji et al.’s49. They performed the energy, exergy and parametric analysis to achieve their system’s optimum performance. At second study, Assareh et al.50 optimized their three green-based (solar-wind-ocean energy) system performance based on energy, exergy and economic criteria as objective functions by using NSGAII algorithm.

Pluralization of literature review and research motivation

Improving system performance from the first and second thermodynamic laws viewpoints, as well as selecting design parameters and minimizing the system cost, are the main aspects of the optimization procedure in thermodynamic systems. Therefore, performing the thermo-economic and thermo-environmental optimization which could be covered all the above purposes, seems to be necessary25,51,52. In this study a green system (WPWVCRS) with detailed operation for all equipment (e.g., VSC, WCT, WT, IST etc.) is considered. Beside the techno-economic evaluation of WPWVCRS, comprehensive thermo-economic-environmental optimization was carried out for it.

System description

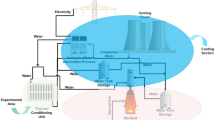

The proposed schematic diagram, presented in Fig. 1, involves three subsystems including, cold production (VCR combined with WCT), storage and distribution (AHU and IST with its two feed-circuit from evaporator and to AHU) and finally power generation subsystem (WT and its related equipment). Due to variable produced power and following it changeable mass flow rates of the system (e.g., VCR, WCT and feed circuits), a variable speed fan is intended by WCT to coordinate with the system’s other parts.

The weather condition and WT modelling are considered based on input data of Ref.8.

The main objective of this study could be represented as following bullets:

-

Carrying out the comprehensive 5E analyses (Energy, Exergy, detailed Economic, Exergo-economic and Environmental)

-

Defining the performance criteria for WPWVCRS based on thermo-economic-environmental aspects.

-

Conducting the parametric analysis to assess the design parameter’s effects on thermo-economic-environmental criteria.

-

Estimating the optimum values of design parameters by GA algorithm by the help of the data bank of parametric analysis

-

Employing an ANN for re-modelling the database results of techno-economic modelling to learn the reliable correlation between the inputs and outputs data for feeding to the main optimization algorithm.

-

Using a triple-objective MPSO optimization algorithm to estimate the most preferred size of each sub-system.

The graphical abstract of solution procedure is presented in Fig. 2.

Mathematical modelling of WPWVCRS

WPWVCRS are modelled based on 5E formulation (e.g., Energy, Exergy, extended Economic, Environmental and Exergo-economic)53. Although the energy, exergy and economic analyses simultaneously are helpful for system assessment, using of them are not enough for its accurate evaluation54. Therefore, thermo-economic-environmental aspects are introduced in system evaluation via the performance criteria. Following, two-stage optimization procedures are employed. The first stage includes using GA to find the best design variables, and the second one is to use ANN for data training and a multi-objective MPSO algorithm to determine the most preferred design parameters and best solutions.

The mass, energy and exergy mathematical formulations (2E analysis)

The flowchart of WPWVCRS thermodynamic modelling is presented in Fig. 3. As this figure, the modelling of WT and IST is existed in Ref.11. The brief balances of energy and exergy equations for WPWVCRS various components are shown in Table 1. Moreover, the formulations for detailed modelling of some effective equipment (e.i., WCT, VSC and HEX) are presented in below sub-sections and avoiding those of stated in Ref.8 such as VCR, WT and IST.

Working principle and formulation of VSC

Due to instability of wind, the feed power to VCR is variable (produced by WT). Therefore, a VSC is required to cover that and its operation and efficiency can affect the system’s performance11,55. VSC main advantage is the better capacity regulation offer than the conventional on/off control for air conditioning and refrigeration system56. Although the reciprocating and scroll compressors are widely used in low-size refrigeration systems, twin-screw compressors have been significantly employed in middle-size cooling systems because of their high efficiency and reliability57,58. So, a variable speed twin screw compressor is considered in the present study.

Although the compressor can be evaluated under the different operational models, the energy and exergy-based models are more comprehensive compared to others11,55. Three kinds of efficiency can be defined for a VSC: volumetric, isentropic and motor/transmission. The suction volume flow rate can be obtained from the volumetric efficiency, defined as the ratio of the refrigerant, and actual volume entering the compressor per its geometric displacement, as below equation11.

Which \({\dot{\text{m}}}_{{{\text{suc}}}}\),\({\text{v}}_{{{\text{suc}}}}\),\({\text{N}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\) and \({\text{V}}_{{{\text{displacement}}}}\) represent the suction mass flow rate, specific volume, compressor shaft speed and volumetric displacement. The pressure ratio and isentropic efficiency are expressed as follows55:

The volumetric efficiency for the pressure ratio ranging between 2 and 9 for the twin-screw compressor is suggested by the below equation59:

Overall compressor’s efficiency is obtained by multiplying the above three efficiencies as follows56:

From the produced useful power by WT, the amounts required to feed some devices (i.e., the pumps of feed circuits to/from IST and WCT, the fans of AHU and WCT) are picked up and the remained power can be fed to VSC. So, it can be expressed as:

The received actual power by VSC is equal to:

The suction mass flow rate into VSC is obtained from:

Heat exchanger formulation

The heat exchanger’s purchase cost is determined based on its thermal surface. If the thermal load is specified, the thermal surface can be obtained from the fundamental equation by estimating the Logarithmic Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD) for counter orientation of two streams crossing over condenser60.

The overall heat transfer coefficient could be calculated as61:

Where \({\text{d}}_{{\text{o}}}\) and \({\text{d}}_{{\text{i}}}\) represent the tube’s outer and inner diameter, \({\text{k}}_{{{\text{tube}}}}\) is the tube wall thermal conductivity coefficient, \({\text{h}}_{{\text{i}}}\) and \({\text{h}}_{{\text{o}}}\) are the tube-side and shell-side convection heat transfer coefficient. Finally,\({\text{F}}_{{\text{o}}}\) and \({\text{F}}_{{\text{i}}}\) indicate the thermal resistances of the fouling on the shell and tube sides and is assumed to be equal to \({\text{F}}_{{\text{o}}} = {\text{F}}_{{\text{i}}} = {\text{9}} \times {\text{10}}^{{ - 6}} [{\text{m}}^{2}\) °C C/kW]61. The formulation set of the \({\text{h}}_{{\text{i}}}\) and \({\text{h}}_{{\text{o}}}\) calculations can be found in Ref.62. The heat exchangers are assumed to be from the shell and tube kind. Also, the tube wall material is supposed to be copper63. The schematic of the pipe alignment was supposed to be triangular with a tube layout angle 45 ° and two passes.

Working principle and formulation of WCT

Higher cooling capacity than the dry ones is WCT’s significant advantage. The temperature and partial pressure differences between air and water, and also unsaturated ambient air are the agent for heat and mass transfer in WCTs64. But the large amounts of water and electricity consumption are the major drawbacks of them65. Several factors (e.g., air and water flow rates, water inlet temperature, air condition, direct or counter flow in interaction between air and water) have effects on WCT operation66. Also, WCT’s inlet and outlet water temperatures are limited by the ambient wet bulb and desired approach temperatures67. Although the minimum of possible temperature in condenser is equal to the air wet-bulb temperature, this value could not achieve at any significant load66. The difference between WCT outlet temperature and air wet-bulb temperature is called the desired approach68. The initial value of that was considered \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{WCT}}}} = 6\) [°C].

In mechanical draft counter-flow WCT, the vaporization is the main manner of heat transfer which includes both sensible and especially latent modes69. Several zero, one-dimensional and classical methods were introduced to calculate the two fluid conditions (air and water). In most models, various simplified assumptions were considered to determine the outlet conditions. For example, treating as saturated state for outlet air even though it does not achieve the complete state of saturation66 such as the Merkel model70 which was the first practical approach for WCT thermal assessments. Also, the evaporative water loss was ignored in this model. Thereafter, more accurate models than that of Merkel were presented in which the deviation in physics of heat and mass transfer in the Markel model compensates71 such as effectiveness-NTU72, the Popp model73 and the Braun model64.

The formulation processes of WCT evaluation can be found in Fig. 3. As this figure, the iterative process with the initial guess for outlet air temperature from WCT69 is designed. The amounts of enthalpy of exit air from WCT are evaluated from two manner. By comparing these values and by satisfying the stop condition equal to \(10^{ - 5}\), the solution procedure is completed and the characteristics of air at the exit od WCT are determined.

3E analysis of techno-environmental aspects

In this section, a comprehensive economic and environmental analysis is presented to introduce a cost-effective system74,75. Both types of economic assessing (e.g., simple approach and combined with exergy concept) are performed. Also, the simple type is applied to calculate the system payback period.

Detailed simple economic approach

The simple economic approach involves all important financial variables such as capital investment (listed in Table 2), installation and related piping, total annual cost, operation and maintenance cost, capital recovery factor, salvage value, annual book depreciation and finally payback period76,77. The capital costs should be updated for the recent years by the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI). The CEPCI for the 2019 year is equal to 607.5 which is used here.

Capital Recovery Factor (\({\text{CRF}}_{{{\text{Capital}}}}\)) is expressed by the following general formula80:

where \({\text{n = 20}}\) represents the lifetime of system equipment and \({\text{i = 0}}{ 1}\) is the annual interest rate81. In an advanced way, a relation is used to calculate the system operation and maintenance cost in terms of the annual interest factor, inflation rate (\({\text{r = 0}}{ 04}\)82) and the system lifetime by the below relation83:

The levelized total capital cost of all equipment can be formulated as:

where \({\text{NN = 5544 [hr]}}\) and \({\text{Z}}_{{{\text{tot}}{ 2019}}}\) are the annual number of working hours and total capital cost of all components except WT, respectively. Also, the piping and jointing structures are considered around 10% of the equipment’s purchase costs63.

The levelized operation and maintenance cost is expressed as follows:

where \({\text{f}}\) is the maintenance factor for \({\text{CRF}}_{{{\text{O}}{\mathrm{ M}}}}\) and equal to 0.01 of capital expenditure84.

For all system equipment except WT, the total levelized cost including capital, operation and maintenance costs can be expressed as the following equation:

The detailed simple economic analysis for WT has been performed separately because of its manufacturing company’s different pricing85. Calculating of WT’s economic procedure is shown in Table 3.

Therefore, the total cost rate of the whole proposed system can be calculated by:

Environmental analysis

The various kinds of pollutant emission particles including \({\text{CO}}_{{2}}\), \({\text{NO}}_{{\text{x}}}\) and \({\text{CO}}\) can affect the global warming issues21. In conventional operation, the required electricity is supplied from the grid, but in the present system, it produces by WT87. Therefore, the emission reduction is estimated based on the pollutant emission factor (\({\upxi }\)) from electricity and the environmental tax factor (\({\text{C}}\)), recorded in Table 4.

The total annual penalty cost of pollutant particles from the electricity is equivalent to produced useful power by WT and is described by the below equation53:

The unit of \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{envr}}}}\) is [$] and levelized into \([\$ /{\text{hr}}]\) by the below equation:

Due to using renewable energy, the environmental penalty cost has to be subtracted from the total cost of the system. So, the system’s total cost can be expressed as follows:

Payback period

The payback period is an assessing technique in which the initial investment of the proposed system will recover after its expiration76. The PP computation process can be found in Table 5.

Exergo-economic analysis

The general equation of exergo-economic cost rate based on the exergy parameters for all system components are expressed as follows53:

where \(\dot{C}[\$ {\text{/h}}]\) named the cost of exergy for outlet and inlet flows, heat transfer and work of the system components. \({\dot{\text{Z}}}\) represented the sum of the capital, operation and maintenance costs of each component. The brief exergo-economic balance equations and required auxiliary relations for each system components have been listed in Table 6.

Overall and partial performance assessment

The proposed system can be divided into two sub-systems: the cold production (including WT and VRC combined with WCT), and the storage and distribution sub-system (including IST and AHU). For assessing the system performance in partial and overall modes, the below criteria were introduced based on the thermodynamic first and second laws. For the cold production sub-system, performance criteria can be expressed as:

Also, these assessment criteria were presented for second sub-system:

Finally, the total energy and exergy efficiencies for overall system were introduced by:

The system’s main goal is to provide NCD. Besides, NCD and stored cooling amounts are not equal at any hour interval. Therefore, the refrigeration amount stored in IST is second goal for the predictability of total system performance. Since the system cost as well as energy and exergy efficiencies are the main effective factors in the system assessment criteria, Product Sum Unit Cost (PSUC) can be defined as follows:

PSUC was defined based on the cost of products per their exergy amounts52. For the introduced system, NCD and stored cold are considered as the products, which imposed the main cost onto the system. Also, WCT outlet air contains the wasted heat from WCT fluid. This removed heat can be prepared to use for any operation, so it can be considered among the products. Also, due to employing green energy to drive the system, the saving penalty cost of pollutant emissions can be considered as a product.

Optimization evaluation

An optimization procedure based on thermo-economic-environmental aspect could be got out all purposes such as determining the best design variables amount and following that achieving the high performance and low cost of thermodynamic system25,51. Optimization technique can be performed via two categories: single and multi-objectives optimizations53. In second category, several techniques were employed such as MPSO-II88 or NSGA-III89. One of the famous machine learning methods is ANN which can be used to find a new pattern for learning and training between inputs and outputs databases of problems90. PSO is a social-based (fish schooling or bird flocks) optimization with quick convergence characteristics by maintaining the balance between exploration and exploitation48. In fact, PSO is efficient in memory requirements and speed91. PSO algorithm has some similarities with evolutionary algorithms such as GA which are based on natural genetics. In comparison between PSO and GA, no evolution operators such as crossover and mutation don’t exist in PSO technique. To optimize WPWVCRS below procedures were followed in order:

-

Performing a parametric analysis to assess the design variable effects on the performance criteria

-

Finding the design parameter best values by using GA algorithm

-

Preparing a data bank from main sizing parameters and performance criteria of the system based on the best design variables resulting from GA optimization

-

Employing ANN intelligence method to prepare the relationship between inputs and outputs variables

-

Proposing the triple-objective MPSO algorithm to evaluate the best size of system

Validation

The problem validation can be divided into two categories: modelling and optimizing procedures. The modelling validation is performed for WT, VCR and WCT. Since the main duty to contact between thermodynamic result and optimization technique belongs to ANN, the validation of the training procedure can guarantee the optimization results.

Validation of modeling

Validation of WT modeling

WT was evaluated based on SABA NIROO S47 660 kW model8. The power generation and waste heat amounts are two indicator of WT performance. The validation results can be seen in Fig. 4 which the results show the high accuracy of WT modelling.

Compared results of WT performance between present study and Ref. 77.

Validation of VCR modeling

VCR which was modelled based on Jain et al.92. They used R717 as VCR’s working fluid by setting \({\text{T}}_{{{\text{evap}}}} = - 30\) °C, \({\text{T}}_{{{\text{cond}}}} = {\text{11}}\) °C for refrigeration production equal to \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{evap}}}} = {\text{100 kW}}\). The results of VCR validation are presented in Table 7.

Validation of WCT modeling

For WCT modelling, the outlet air temperature should be guessed and can be specified with the iterative procedure66. In the same direction, the water evaporation loss amount can be selected to compute again by the below relation65:

Which \({\text{W}}_{{{\text{e}}{ 0}}}\) and \({\Delta W}_{{\text{e}}}\) represent the water consumption (the vaporized water amount required to transfer heat from water to air) and water consumption for air self-cooling, respectively. These two parameters are calculated as follows:

Which \({\text{h}}_{{{\text{f}}{\mathrm{ g}}{\mathrm{ CWT}}{\mathrm{ w}}}}\) represented the latent heat of vaporization. The comparison between two equation’s results for water evaporation loss amount represents in Fig. 5 by about 11% maximum error.

Validation results for WCT between present work and Ref.65.

Validation of trained data for optimization by ANN

ANN technique was employed to train and fit a reliable correlation between thermodynamic modelling data and MPSO algorithm. Three objective functions were presented by Eqs. (25), (26) and (28). For each of them, ANN was trained separately. It performance can be evaluated by a standard statistical criterion namely Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) as the following:

The comparison between the outputs data of the system modelling and target data from ANN training are shown in Fig. 6. As a result, ANN’s predicted data have good accuracy compared with the actual data. The value of the RMSE is demonstrated above each plot of this figure.

Results and discussions

R141b was obtained as the best working fluid for wind-powered VCR system in Zabol-Iran operation condition according to Ref.8 results. In present study, three general aspects are evaluated including the thermodynamic and thermo-economic results and also optimization outcomes.

Whether conditions

As Fig. 7, wind speed and ambient temperature amounts change during the day with the opposite trend. Two highest wind speeds are achievable at 4 a.m. and 24 p.m. so at these two hours, more electricity is produced by WT. Since reducing of the pollutants is the main effect of using green systems, saving environmental penalty costs are increased by enhancing electricity production by WT. The highest and least values of environmental penalty cost occur at 4 a.m. and 4 p.m., respectively which exactly corresponds to the wind speed.

Parametric analysis

Parametric analysis can be useful in assessing the design parameter’s effects on the performance criteria 93. This is an effective step to evaluate the size improvement of the system. These design variables include compressor transmission efficiency, compressor pressure ratio, evaporator temperature, approach value of WCT. To assess the impact of each parameter, all objective functions (Eqs. (25,26,28)) are evaluated by changing in the ambient temperature, wind speed and NCD simultaneously during every hour of design day. Finally, the daily average of each of them were computed and reported.

The effect of compressor transmission efficiency

The compressor is one of the critical equipment in proposed WPWVCRS because the variable power production by WT should be received by compressor and feed to system. Therefore, its performance optimization can play a significant role in improving the system efficiency. Compressor performance is dependent on the various parameters such as three kinds of compressor efficiencies, pressure ratio etc.94,95. Two of compressor efficiencies (volumetric and isentropic efficiencies) have a relationship with the pressure ratio of the compressor. The compressor transmission efficiency has significant effect because of its role in received work from WT which can affect WPWVCRS efficiency. In this study, the initial guess of motor/transmission efficiency was considered to be \({\upeta }_{{{\text{cc}}{\mathrm{ com}}}} { = 0}{\text{ 8}}\)94.

As the results of Fig. 8, the variation of transmission efficiency between 0.6 and 0.85 don’t have much affected in COP and exergy efficiency of VCR sub-system. According to Eq. (7), increasing of \({\upeta }_{{{\text{cc}}}}\) leads to the growth in the received work by the compressor, in following the cooling production is enhanced too. These two variables are used in the numerator and denominator of \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{VCR}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ VCR}}}}\) criteria. Therefore, their amounts fluctuate and vary in ranges of 2.12– 2.11%. For the storage and distribution subsystem,\({\text{COP}}_{{\text{ISB - AHU}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ ISB - AHU}}}}\) have a decreasing trend in this range. because, the NCD amounts are kept constant whereas \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{8 - 9}}\) are augmented with increasing refrigeration amount. Thus, the reduction of energy and exergy efficiencies of the storage and distribution sub-system is logical. For WPWVCRS, a sudden descent is occurred at the beginning of its trend, in the following, an almost decreasing procedure can be seen. With \({\upeta }_{{{\text{cc}}}}\) increasing, the amount of \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{6 - 7}}\) is ascended about 30% but \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{store}}}}\) has decreasing trend with maximum variation about 3%. Changes in the numerator and denominator of total COP and exergy efficiency have happened at the same time. Therefore,\({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ WPWVCRS}}}}\) don’t show much vicissitude and experience little fluctuations about 3.5% and 7%, respectively. For interval changes between 0.85 and 0.95 of \({\upeta }_{{{\text{cc}}}}\), the opposite trend for the sub-system’s criteria can cover each other. Thus, the total criteria had a smooth trend. Also, \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}}}\) is continuously decreased with enhancing of \({\upeta }_{{{\text{cc}}}}\).

The effect of compressor pressure ratio

Figure 9 illustrates \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\) influence on the system performance. COP of VCR sub-system is reduced with increasing of \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\). If the pressure ratio is enhanced, the outlet temperature of the compressor will be augmented and subsequently, the enthalpy is increased. Therefore, the compressor work can be ascended which causes a decrement in \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{VCR}}}}\) but temperature change due to \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\)’s one and its effect on exergy efficiency, an increasing trend in that can be seen. By remaining constant of fluid’s condition in outlet from the condenser (6 °C more than the inlet fluid’s temperature of WCT), the evaporator load is decreased and \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{8 - 9}}\) has similar trend with \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{evap}}}}\). Therefore,\({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{ISB}}{\mathrm{ AHU}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ ISB}}{\mathrm{ AHU}}}}\) are grown with ascending of \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\). Regarding COP and exergy efficiency of WPWVCRS, \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{Store}}}}\) has an increase by about 10% more than \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{6 - 7}}\). Therefore, \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ WPWVCRS}}}}\) have almost gone through an increasing trend. It is worth mentioning that an initial descent of \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ WPWVCRS}}}}\) was occurred due to moving away belonging to condenser’s leaving fluid from saturation condition. Also, economic-environmental criteria move in an almost upward path with \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\)’s increments. With enhancing compression ratio, the compressor capital cost is ascended, thus it shows its effect on \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}}}\).

The subcooling degree for each pressure ratio is demonstrated in Table 8. Although an expansion valve can have better performance at a high subcooling degree, energy, exergy and economic-environmental consideration play key roles in selecting the best operating condition for condenser outlet fluid, which is also affected by the compression ratio.

The effect of evaporator temperature

Figure 10 represents the evaporator temperature effects on the examination criteria. Based on the thermodynamic concepts, if the lower temperature difference exists between the evaporator and the environment, the higher efficiency of the cooling cycle can be obtained. Hence, the upward trend of COP and exergy efficiency for VCR sub-system are logical. When the evaporator and ambient temperatures reaches to same value, the produced refrigeration is decreased. After that \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{8 - 9}\) will decreased too. Therefore, supplying NCD may be more difficult and reduce the ratio of \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{NCD}}}}\) to \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{8 - 9}\). So, \({\text{COP}}_{{\text{ISB - AHU}}}\) decline. Whereas \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ ISB - AHU}}}}\) is also affected by feed temperatures and can increase. The exergy efficiency and COP of the total system have fluctuations with maximum values of nearly 2% and 5% in this interval. But \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}}}\) is continuously descends with ascending the evaporator temperature and VCR energy efficiency.

The effect of WCT’s approach value

The WCT’s best performance can be achieved with the least temperature differences (i.e., zero) between the outlet fluid of WCT and ambient wet bulb temperatures. But in practice, this is not possible. The initial value of the approach is considered equal to \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{WCT}}}} = {\text{6}}\) °C in this study. Figure 11 demonstrates \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{WCT}}}}\)‘s influence on the defined assessing standard. At the lowest \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{CT}}}}\) value, VCR sub-system has its maximum COP and exergy efficiency while IST-AHU sub-system has a reverse trend. With approach temperature changing,\({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ WPWVCRS}}}}\) have a slightly decreasing trend up to \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{WCT}}}} = {\text{5}}\) °C and after that a rise can be seen by about 2% and% for COP and exergy efficiency, respectively. \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}}}\) has the same trend as that of \({\text{App}}_{{{\text{WCT}}}}\).

Thermo-economic results based optimum design parameters by using GA

Following parametric analysis for evaluating the impact of design parameters on assessing criteria, at first one-objective GA algorithm is employed to determine the best amounts of design parameters. These specified values, are substituted into the model then thermo-economic properties of the system at various stream positions are reported. Moreover, the energy results (heat or work), exergy destruction and cost of exergy destruction for each component of the proposed system are estimated. Secondly, hourly variation of temperature, wind velocity and their effects on the generated power by WT and environmental penalty profit are evaluated in the next subsection at design day. At last, the payback period and its dependent variables are reported. At the end, the optimum size of each constituent subsystem WPWVCRS are estimated with the help of the three-objective MPSO technique.

The optimum design parameters using GA

In section "Whether conditions", each design parameter’s impacts on the objective functions were evaluated. This appraisement was done case by case for each of them while one parameter was changing and other of them kept constant in each step. So, determining the best design values with the simultaneous examination of all variables is the existing gap of that. This can be covered by using an optimization technique by the help of the weight function method. Therefore, a one-objective GA is employed with the below relation including thermo-economic-environmental criteria:

where all criteria have the same portion of \({\text{Inv}}_{{{\text{EOF}}}}\) with weight coefficients \({\text{w}}_{{1}} = {\text{w}}_{{2}} = {\text{w}}_{{3}} { = 1/3}\). The results of GA optimization can be found in Table 9. Two times with NCD’s minimum and maximum amounts select for optimization calculations. Although \({\text{Inv}}_{{{\text{EOF}}}}\) has a lower value in minimum NCD at 6 a.m., optimum design parameters of maximum NCD state are selected as the best design variables of WPWVCRS. Because the difference of \({\text{Inv}}_{{{\text{EOF}}}}\) is equal to 18% between these two assessed states. Also, it is so important that WPWVCRS can have good response in maximum NCD on the year’s hottest day. In this regard, the old optimum design variables were replaced by new ones. The comparison between the initial and optimum design variable’s effects on the thermo-economic-environmental criteria were shown in Table 10. As the results, all criteria are improved after optimization except exergy efficiency of VCR sub-system. But it is not important because the focus of this optimization is on the WPWVCRS performance and its cost, which show good improvement by using GA optimization.

Thermodynamic and thermo-economic characteristics

By the help of parametric analysis and using of GA optimization, the appropriate values of various design variables are determined and substituted in the main model. By changing the climate conditions in every hour of design day, some properties may be changed. Accordingly, the average daily thermodynamic and economic properties of different stream situations based on various situation of numbered stream shown in Fig. 1 are calculated and presented in Table 11.

Table 12 illustrates the results of energy balance, exergy destruction and the cost of exergy destruction for various components of WPWVCRS. About 67% of produced power is received by the compressor. AHU’s transferred cooling was considered to be equal the daily average of NCD amount for discharge time (6 a.m.-23 p.m.), which were about 3% more than the daily average stored refrigeration in IST. This excess value could not exchange IST water ‘s temperature significantly. Therefore, the water temperature of IST was supposed to be remained at 0 °C. As the result, WT and Pu1 had the largest and smallest exergy destruction amounts equal about \({\text{561 kW}}\) and \({0}{\text{ 04 kW}}\), respectively. Although WT had the maximum exergy destruction of all equipment, the maximum cost of exergy destruction belongs to AHU. Because the main cost of system is paid for providing of NCD. Therefore, the unit cost per exergy of this point possibly has the biggest value. IST had the second rank in exergy destruction. Processes occurring in IST include heat transfer (\({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{\text{l}}}\), \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{8 - 9}}\) and \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{11 - 13}}\)), freezing and melting of IST fluid. On the other hand, the large heat amounts can be transferred in IST, as shown in energy balance results. But its exergy destruction cost is small because the unit cost of exergy destruction of IST fluid is very low (i.e., equal to \(0.{\text{00593}}\$ /{\text{Wh}}\)).

Payback period

A comprehensive process was applied to evaluate PP of the whole system with considering all effective parameters based on Table 5 formulations. Table 13 contains the economic data namely PP which was estimated about 450 days. The high wind potential of the Sistan-Iran region (almost 250 days in the year with a speed up to 50 km/h 96) and the useful generated power by WT84 can confirm the truth of this matter.

For 12000 m2 floor areas with a comfortable temperature equal to \({\text{25}}^\circ {\text{C}}\),the case study under consideration, a \({\text{500 ton}}\) compression chiller is required for Zabol-Iran weather conditions to supply NCD. The York YT 1758 W/5.76 COP/ VSD chiller model is selected as a conventional system fed by grid electricity. Considering the electricity price equal to \({\text{c}}_{{{\text{elec}}}} = 0.{\text{115}}\$ /{\text{kWh}}\), PP of this conventional system is estimated about 765 days which is 41% more than received PP of WPWVCRS.

The optimum sizing of each subsystem of WPWVCRS

Each of three sub-systems (i.e., WT, VCR and IST) of WPWVCRS should have its optimum size in such a way that can have the best influence on the system’s performance. Three objective functions were defined in this study by Eqs. (25–28). Three parameters that represent each sub-system size are:\({\text{W}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\), \({\dot{\text{m}}}_{{{\text{VCR}}}}\) and \({\text{V}}_{{{\text{ISB}}}}\). Generated useful power by WT was fed to VSC. According to Eqs. (6–7),\({\text{W}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\) is related to \({\text{Po}}_{{{\text{us}}{\mathrm{ WT}}}}\). VCR sizing can be evaluated by \({\dot{\text{m}}}_{{{\text{VCR}}}}\) and the optimum size of IST-AHU sub-system is determined by IST’s size. After substituting the best design variable amounts, triple objective MPSO algorithm is employed to estimate the optimum values of thermo-economic-environmental performance criteria and size of the various parts of WPWVCRS system. The Pareto frontier of the three-objective MPSO optimization algorithm is shown in Fig. 12.

The best value of the objective function and decision variable (size of sub-systems) is demonstrated in Table 14. The optimum value of \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) are about 0.85 and 16.60% with exergo-economic-environmental cost index of around 470. IST optimum volume determined equal to \({\text{283 m}}^{{3}}\) which has a 22% decrease in comparison by the initial value (\({\text{361 m}}^{{3}}\)). The optimum value of VSC’s fed work was appraised equally to the maximum value of the interval. This means that the selected WT by 660kW maximum power generation was the appropriate choice for this proposed system. The Optimum mass flow rate of VCR was computed 2.57 kg/s at which the optimum evaporator required surface can be obtained equal to 265.8 m2.

Conclusion

In this study a Wind-Powered Water-cooled Vapor Compression Refrigeration cycle with a Storage tank system (WPWVCRS) was considered. VSC and WCT’s fan was employed to overcome of instability of wind power beside IST to store generated refrigeration. The comprehensive 5E analysis (i.e., Energy, Exergy, detailed Economic, Exergo-economic and Environmental) was carried out for evaluating the system performance. By using GA optimization algorithm based on databank of parametric analysis, the best design variable amounts were estimated which showed good improvement in system performance criteria. The optimum size of system effective equipment was determined by using ANN combined with a triple-objective MPSO optimization.

Considering the result, the following items can be mentioned:

-

The maximum exergy destruction belonged to WT, and the next rank was related to IST. But AHU had the maximum cost of exergy destruction. Also, this point had the highest unit cost per exergy value because the costs were paid for the whole system that had been made to provide it as a desired product.

-

One of the advantages of the proposed system was its PP in Zabol-region with high wind potential. The proposed zero emission system’s PP was determined about 450 days whereas that of the conventional system was about 765 days. IST effectiveness along with the use of wind power had caused a reduction in PP by about 41%.

-

At design day, the maximum wind speed and WT power generation occurred at 4 a.m. as well as the saving environment penalty cost. The minimum of these variables occurred at 4 Pm at which the ambient temperature and NCD had high values. At this hour, power production was low. Therefore, IST had an effective role in providing NCD. Also, COP and exergy efficiency of AHU-IST sub-system and WPWVCRS were defined based on that had an essential role in supplying NCD. Therefore, COP and exergy efficiency had their highest value at that time, showing a similar trend to WPWVCRS assessment criteria too.

-

After determining the best design variable amounts with the help of parametric analysis and GA optimization at maximum NCD time, these values were replaced in WPWVCRIS modelling. The daily average values of \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}{\mathrm{ daily}}}}\) and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{ex}}{\mathrm{ WPWVCRS}}{\mathrm{ daily}}}}\) had been augmented up to 98% and 40% respectively whereas \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}{\mathrm{ ave}}{\mathrm{ daily}}}}\) had shown enhancement of about 10%.

-

The final optimum thermo-economic-environmental criteria of WPWVCRS was determined by using a three-objective MPSO algorithm. The optimum values of \({\text{COP}}_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\), \({\upeta }_{{{\text{WPWVCRS}}}}\) and \({\text{PSUC}}_{{{\text{non}}{\mathrm{ Dim}}}}\) are appraised equal to 0.85, 16.6% and 470, respectively. Also, the optimum size of WPWVCRS’s various parts was demonstrated selected wind turbine was suitable. But IST’s volume had a 22% reduction. VCR’s optimum mass flow rate was estimated equal to \({2}{\text{ 57 kg/s}}\).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({\text{A}}\) :

-

Area \(\left( {{\text{m}}^{{2}} } \right)\)

- \({\text{C}}\) :

-

Capacity Factor–Cost ($/h)

- \({\text{c}}\) :

-

Average cost per unit of exergy ($/wh)

- \({\text{CR}}_{{{\text{com}}}}\) :

-

Compression ratio of com

- \({\text{d}}\) :

-

Diameter \(\left( {\text{m}} \right)\)

- \({\text{E}}\) :

-

System rate of energy (J/s)-evaporation amount \({\text{(kg/s)}}\)

- \({\dot{\text{E}}\text{x}}\) :

-

Rate of exergy \(\left( {\text{J/s}} \right)\)

- \({\text{F}}\) :

-

Thermal resistances of the fouling (m2 °C/KW)

- \({\text{g}}\) :

-

Gravitation (m/s2)

- \({\text{h}}\) :

-

Enthalpy (J/kg)-convection heat transfer coefficient (W/m2 °C)

- \({\text{hr}}\) :

-

Hour

- \({\text{i}}\) :

-

Interest ratio

- \({\text{k}}\) :

-

Weibull shape factor

- \({\dot{\text{m}}}\) :

-

Mass flow ratio \(\left( {\text{kg/s}} \right)\)

- \({\text{n}}\) :

-

System lifetime \({\text{(year)}}\)

- \({\text{NN}}\) :

-

System lifetime in a year \({\text{(hr)}}\)

- \({\text{P}}\) :

-

Pressure \(\left( {{\text{Pa}}} \right)\)

- \({\text{Po}}\) :

-

Power \(\left( {{\text{Whr}}} \right)\)

- \({\dot{\text{Q}}}\) :

-

Rate of heat (J/s)

- \({\text{r}}\) :

-

Inflation rate (%)

- \({\text{R}}\) :

-

IST thermal resistance((m2)K/W)-Gas constant (J/K)

- \({\text{s}}\) :

-

Entropy (J/kg K)

- \({\text{t}}\) :

-

Time \(\left( {\text{s}} \right)\)

- \({\text{T}}\) :

-

Temperature (°C)

- \({\text{U}}\) :

-

Overall heat transfer coefficient \({\text{(W/m}}^{2} \;{\text{K)}}\)

- \({\text{v}}\) :

-

Velocity \(\left( {\text{m/s}} \right)\)

- \({\text{V}}\) :

-

The volume of storage tank \(\left( {{\text{m}}^{{3}} } \right)\)

- \({\dot{\text{W}}}\) :

-

Rate of work \(\left( {\text{J/s}} \right)\)-evaporation loss amount \({\text{(kg/s)}}\)

- \({\text{z}}\) :

-

Elevation \(\left( {\text{m}} \right)\)-Capital cost ($)

- AHU:

-

Air handling unit

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- COP:

-

Coefficient of performance

- CRF:

-

Capital recovery factor

- Ed:

-

Exergy destruction

- Eff:

-

Effectiveness

- EOF:

-

Equivalent objective function

- Ex:

-

Exergy

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- HVAC:

-

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

- Inv:

-

Inverse

- IST:

-

Ice storage tank

- LMTD:

-

Logarithmic mean temperature difference

- MPSO:

-

Modified particle swarm optimization

- NCD:

-

Needful cooling demand

- NSGAII:

-

Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm

- PCM:

-

Phase change material

- PO:

-

Power

- PSO:

-

Particle swarm optimization

- PSUC:

-

Product sum unit cost

- PP:

-

Payback period

- VCR:

-

Vapor compression refrigeration

- VFD:

-

Variable frequency drive

- VSC:

-

Variable speed compressor

- \({\text{w}}_{{\text{i}}}\) :

-

Inlet water to WCT

- \({\text{w}}_{{\text{o}}}\) :

-

Outlet water from WCT

- WCT:

-

Wet cooling tower

- WPWVCRS:

-

Wind powered water cooled vapor VCR cycle with Storage tank

- WT:

-

Wind turbine

- WVCR:

-

Water cooled vapor compression refrigeration

- \({\upeta }\) :

-

Efficiency

- \({\upmu }\) :

-

Dynamic fluid viscosity \({\text{(N}}{\mathrm{ m}}^{{2}} {\text{/s)}}\)

- \({\upxi }\) :

-

Pollutant emission \({\text{(kg/kWh)}}\)

- \({\uppi }\) :

-

The ratio of a soluble particle

- \({\uprho }\) :

-

Density \(\left( {{\text{kg/m}}^{{3}} } \right)\)

- \({\upomega }\) :

-

Specific humidity (Kgv/Kga)

- ambn:

-

Ambient

- ave:

-

Average

- cc:

-

Motor/transmission coefficient

- com:

-

Compressor

- con:

-

Condenser

- env:

-

Environment

- eva:

-

Evaporator

- Ex.V:

-

Expansion valve

- gen:

-

Generator/generation

- h:

-

Hour

- i:

-

Input

- is:

-

Isentropic

- l:

-

Leakage

- o:

-

Output

- O.M:

-

Operation and maintenance

- Po:

-

Power

- \({\text{Pr}}\) :

-

Prandtl number

- Pu:

-

Pump

- \({\text{Re}}\) :

-

Reynolds number

- s.a:

-

Swept area

- suc:

-

Suction

- us:

-

Useful

- v:

-

Volumetric

- wb:

-

Wet bulb

- Wi:

-

Wind

References

Li, S., Pan, Y., Wang, Q. & Huang, Z. A non-cooperative game-based distributed optimization method for chiller plant control. Build. Simul. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12273-021-0869-5 (2020).

Jia, L., Wei, S. & Liu, J. A review of optimization approaches for controlling water-cooled central cooling systems. Build Environ. 203, 108100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108100 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Modeling and configuration optimization of the natural gas-wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen integrated energy system : A novel deviation satisfaction strategy. Energy Convers Manag. 243, 114340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114340 (2021).

Liu, J., Zhou, Y., Yang, H. & Wu, H. Net-zero energy management and optimization of commercial building sectors with hybrid renewable energy systems integrated with energy storage of pumped hydro and hydrogen taxis. Appl. Energy 321, 119312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119312 (2022).

Yi, T. et al. Energy storage capacity optimization of wind-energy storage hybrid power plant based on dynamic control strategy. J. Energy Storage 55, 105372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.105372 (2022).

Tiwari, R. & Babu, N. R. Recent developments of control strategies for wind energy conversion system. Renew. Sustain Energy Rev. 66, 268–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.08.005 (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Energy and exergy analysis of a novel direct-expansion ice thermal storage system based on three-fluid heat exchanger module. Appl. Energy 330, 120371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120371 (2023).

Miri, S. M., Farzaneh-gord, M. & Kianifar, A. Evaluating the dynamic behaviour of wind-powered compression refrigeration cycle integrated with an ice storage tank for air conditioning application. Energy Convers Manag. 269, 116093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116093 (2022).

Mahdavia, S., Shiria, M. E. & Rahnamayanb, S. Metaheuristics in large-scale global continues optimization: A survey. Inform. Sci. 295, 407–428 (2015).

Farzaneh-gord, M., Reza, H., Mohseni-gharesafa, B., Toikka, A. & Zvereva, I. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering Accurate determination of natural gas compressibility factor by measuring temperature, pressure and Joule-Thomson coefficient : Artificial neural network approach Equations of State. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 202, 108427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108427 (2021).

Yang, L., Zhao, L., Zhang, C. & Gu, B. Loss-efficiency model of single and variable-speed compressors using neural networks ` le de la diminution d ’ efficacite ´ des compresseurs Mode ` vitesse variable a ` l ’ aide de re ´ seaux neuronaux simples et a. Int. J. Refrig. 32, 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2009.03.006 (2009).

Kalogirou, S. A. Optimization of solar systems using artificial neural-networks and genetic algorithms. Appl. Energy 77, 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-2619(03)00153-3 (2004).

She, X. et al. Energy-efficient and -economic technologies for air conditioning with vapor compression refrigeration: A comprehensive review. Appl. Energy 232, 157–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.09.067 (2018).

Al-Otaibi, D., Dincer, I. & Kalyon, M. Thermoeconomic optimization of vapor- compression refrigeration systems. Int. Commun. Heat mass Transfer 31, 95–107 (2004).

Deymi-dashtebayaz, M., Maddah, S. & Fallahi, E. Thermo-economic-environmental optimization of injection mass flow rate in the two-stage compression refrigeration cycle ( Case study : Mobarakeh steel company in Isfahan, Iran ) Optimisation thermo-économico-environnmentale du débit massique d ’ injection dans un cycle frigorifique à compression bi-étagée ( étude de cas : Mobarakeh steel company à Ispahan, Iran ). Int. J. Refrig. 106, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2019.06.020 (2019).

Ustaoglu, A., Kursuncu, B., Alptekin, M. & Gok, M. S. Performance optimization and parametric evaluation of the cascade vapor compression refrigeration cycle using Taguchi and ANOVA methods. Appl. Therm. Eng. 180, 115816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115816 (2020).

Selbas, R., Kızılkan, Ã. & Arzu, S. Thermoeconomic optimization of subcooled and superheated vapor compression refrigeration cycle. Energy 31, 2108–2128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2005.10.015 (2006).

Kong, D., Yin, X., Ding, X., Fang, N. & Duan, P. Global optimization of a vapor compression refrigeration system with a self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm. Appl. Therm. Eng. 197, 117427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.117427 (2021).

Zhao, L., Cai, W., Ding, X. & Chang, W. Model-based optimization for vapor compression refrigeration cycle. Energy 55, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2013.02.071 (2013).

Zhao, L., Cai, W. J., Ding, X. D. & Chang, W. C. Decentralized optimization for vapor compression refrigeration cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 51, 753–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.10.001 (2013).

Aminyavari, M., Naja, B., Shirazi, A. & Rinaldi, F. Exergetic, economic and environmental (3E ) analyses, and multi- objective optimization of a CO 2 / NH 3 cascade refrigeration system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 65, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.12.075 (2014).

Roy, R. Thermo-economic Assessment and Multi-Objective Optimization of Vapour Compression Refrigeration System using Low GWP Refrigerants. In 2019 8th Int Conf Model Simul Appl Optim, 2019:1–5.

Sayyaadi, H. & Nejatolahi, M. Multi-objective optimization of a cooling tower assisted vapor compression refrigeration system ` me frigorifique a ` compression de Optimisation d ’ un syste ´ d ’ une tour de refroidissement mene ´ e avec vapeur dote plusieurs objectifs. Int. J. Refrig 34, 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2010.07.026 (2010).

Khanmohammadi, S., Kizilkan, O. & Waly, F. Tri-objective optimization of a hybrid solar-assisted power- refrigeration system working with supercritical carbon dioxide. Renew. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.11.155 (2019).

Ghaebi, H. & Rostamzadeh, H. Design and optimization of a novel dual-loop bi-evaporator ejection/compression refrigeration cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.01.114 (2019).

Zhar, R., Allouhi, A., Ghodbane, M., Jamil, A. & Lahrech, K. Parametric analysis and multi-objective optimization of a combined organic rankine cycle and vapor compression cycle. Sustain Energy Technol. Ass. 47, 101401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101401 (2021).

Salim, M. S. & Kim, M. Multi-objective thermo-economic optimization of a combined organic Rankine cycle and vapour compression refrigeration cycle. Energy Convers Manag. 199, 112054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112054 (2019).

Ashwni, Faizan, A. & Tiwari, D. Exergy, economic and environmental analysis of organic Rankine cycle based vapor compression refrigeration system Analyse exergétique, économique et environnementale d ’ un système frigorifique à compression de vapeur basé sur le cycle organique de Rankine. Int. J. Refrig. 126, 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.02.005 (2021).

Patel, B., Desai, N. B. & Kachhwaha, S. S. Optimization of waste heat based organic Rankine cycle powered cascaded vapor compression-absorption refrigeration system. Energy Convers Manag. 154, 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.11.045 (2017).

Ora, E., de Gracia, A., Castell, A., Farid, M. M. & Cabeza, L. F. Review on phase change materials (PCMs) for cold thermal energy storage applications. Appl. Energy 99, 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.03.058 (2012).

Tam, A., Ziviani, D., Braun, J. E. & Jain, N. Energy & buildings development and evaluation of a generalized rule-based control strategy for residential ice storage systems. Energy Build. 197, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.05.040 (2019).

Henze, G. P. Parametric study of a simplified ice storage model operating under conventional and optimal control strategies. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Trans. ASME 125, 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1530629 (2003).

Chen, H., Wang, D. W. P. & Chen, S. Optimization of an ice-storage air conditioning system using dynamic programming method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 25, 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2003.12.006 (2005).

Song, X., Zhu, T., Liu, L. & Cao, Z. Study on optimal ice storage capacity of ice thermal storage system and its in fl uence factors. Energy Convers Manag. 164, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.03.007 (2018).

Luo, N., Hong, T., Li, H., Jia, R. & Weng, W. Data analytics and optimization of an ice-based energy storage system for commercial buildings. Appl. Energy 204, 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.07.048 (2017).

Sanaye, S., Fardad, A. & Mostakhdemi, M. Thermoeconomic optimization of an ice thermal storage system for gas turbine inlet cooling. Energy 36, 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2010.12.002 (2011).

Badar, M. A., Zubair, S. M., Abdulghani, A. & Al-Farayedhi, A. Second-law-based thermoeconomic optimization of a sensible heat thermal energy storage system. Energy 18(6), 641–649 (1993).

Akif, M., Erek, A. & Dincer, I. Energy and exergy analyses of an ice-on-coil thermal energy storage system. Energy 36, 6375–6386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2011.09.036 (2011).

Sanaye, S. & Shirazi, A. Thermo-economic optimization of an ice thermal energy storage system for air-conditioning applications. Energy Build. 60, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.12.040 (2013).

Sanaye, S. & Hekmatian, M. Ice Thermal Energy Storage ( ITES ) for air-conditioning application in full and partial load operating modes. Int. J. Refrig. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2015.10.014 (2015).

Habeebullah, B. A. Economic feasibility of thermal energy storage systems. Energy Build. 39, 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2006.07.006 (2007).

Sanaye, S. & Khakpaay, N. Thermo-economic multi-objective optimization of an innovative cascaded organic Rankine cycle heat recovery and power generation system integrated with gas engine and ice thermal energy storage. J. Energy Storage 32, 101697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101697 (2020).

Shirazi, A., Najafi, B., Aminyavari, M., Rinaldi, F. & Taylor, R. A. Thermal e economic e environmental analysis and multi-objective optimization of an ice thermal energy storage system for gas turbine cycle inlet air cooling. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.02.071 (2014).

Zejli, D., Ouammi, A., Sacile, R., Dagdougui, H. & Elmidaoui, A. An optimization model for a mechanical vapor compression desalination plant driven by a wind/PV hybrid system. Appl. Energy 88, 4042–4054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.04.031 (2011).

Yang, Y., Guo, S., Liu, D., Li, R. & Chu, Y. Operation optimization strategy for wind-concentrated solar power hybrid power generation system. Energy Convers Manag. 160, 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.01.040 (2018).

Yang, J., Yang, Z. & Duan, Y. Capacity optimization and feasibility assessment of solar-wind hybrid renewable energy systems in China. J. Clean. Prod. 368, 133139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133139 (2022).

Lorestani, A. & Ardehali, M. M. Optimal integration of renewable energy sources for autonomous tri-generation combined cooling, heating and power system based on evolutionary particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.12.155 (2018).

Soheyli, S., Shafiei Mayam, M. H. & Mehrjoo, M. Modeling a novel CCHP system including solar and wind renewable energy resources and sizing by a CC-MOPSO algorithm. Appl. Energy 184, 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.09.110 (2016).

Ji, W. et al. Thermodynamic analysis of a novel hybrid wind-solar-compressed air energy storage system. Energy Convers Manag. 142, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.02.053 (2017).

Assareh, E., Assareh, M., Mojtaba, S. & Jalilinasrabady, S. An extensive thermo-economic evaluation and optimization of an integrated system empowered by solar-wind-ocean energy converter for electricity generation – Case study : Bandar Abas, Iran. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 25, 100965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2021.100965 (2021).

Ahmadi, P., Dincer, I. & Rosen, M. A. Exergy, exergoeconomic and environmental analyses and evolutionary algorithm based multi-objective optimization of combined cycle power plants. Energy 36, 5886–5898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2011.08.034 (2011).

Ebadollahi, M., Rostamzadeh, H., Ghaebi, H. & Amidpour, M. Exergoeconomic analysis and optimization of innovative cascade bi-evaporator electricity / cooling cycles with two adjustable cooling temperatures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 152, 890–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.02.110 (2019).

Ebrahimi-moghadam, A., Jabari, A. & Farzaneh-gord, M. Comprehensive techno-economic and environmental sensitivity analysis and multi-objective optimization of a novel heat and power system for natural gas city gate stations. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121261 (2020).

Ebrahimi, M. & Ahookhosh, K. Integrated energy-exergy optimization of a novel micro-CCHP cycle based on MGT-ORC and steam ejector refrigerator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 102, 1206–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.04.015 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. Thermodynamic analysis of NH 3 / CO 2 cascade refrigeration system with thermosyphon refrigerant cooling screw compressor motor. Int. J. Refrig. 130, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.06.032 (2021).

Li, W. Simpli fied steady-state modeling for variable speed compressor. Appl. Therm. Eng. 50, 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.08.041 (2013).

Shen, J., Chen, W., Yan, S., Zhou, M. & Liu, H. Study on the noise reduction methods for a semi-hermetic variable frequency twin-screw refrigeration compressor Étude sur les méthodes d ’ insonorisation pour un compresseur frigorifique semi-hermétique à fréquence variable et à double vis. Int. J. Refrig. 125, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2020.12.029 (2021).

Yu, F. W. Ã. & Chan, K. T. Modelling of the coefficient of performance of an air-cooled screw chiller with variable speed condenser fans. Build. Environ. 41, 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.02.002 (2006).

Li, X., Li, Y., Seem, J. E. & Li, P. Dynamic modeling and self-optimizing operation of chilled water systems using extremum seeking control. Energy Build. 58, 172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.12.010 (2013).

Sanaye, S. & Hajabdollahi, H. Multi-objective optimization of shell and tube heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 30, 1937–1945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2010.04.018 (2010).

Jain, V., Sachdeva, G. & Kachhwaha, S. S. NLP model based thermoeconomic optimization of vapor compression – absorption cascaded refrigeration system. Energy Convers Manag. 93, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.12.095 (2015).

Kalac, S. & Liu, H. Heat exchengers and thermal design 2nd edn. (CRC Press LLC, 2002).

Jain, V., Sachdeva, G. & Kachhwaha, S. S. Energy, exergy, economic and environmental (4E) analyses based comparative performance study and optimization of vapor compression-absorption integrated refrigeration system. Energy 91, 816–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.08.041 (2015).

Naik, B. K. & Muthukumar, P. A novel approach for performance assessment of mechanical draft wet cooling towers. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.04.042 (2017).

Alasseri, R. Measurable energy savings of installing variable frequency drives for cooling towers ’ fans, compared to dual speed motors. Energy Build. 67, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.07.081 (2013).

Liao, J., Xie, X., Nemer, H., Claridge, D. E. & Culp, C. H. A simpli fied methodology to optimize the cooling tower approach temperature control schedule in a cooling system. Energy Convers Manag. 199, 111950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111950 (2019).

Ruiz, J., Navarro, P., Hernández, M., Lucas, M. & Kaiser, A. S. Thermal performance and emissions analysis of a new cooling tower prototype. Appl. Therm. Eng. 206, 118065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.118065 (2022).

Dehaghani, S. T. & Ahmadikia, H. Retrofit of a wet cooling tower in order to reduce water and fan power consumption using a wet / dry approach. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.069 (2017).

Zargar, A. et al. Numerical analysis of a counter-flow wet cooling tower and its plume. Int. J. Thermofluids 14, 100139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijft.2022.100139 (2022).

Merkel V-F, V.D.I.F. Verdunstungskühlung, no. 275, Verdunstungskuhlung. Berlin, Germany: VDI Forschungsarbeiten (1925).

Guo, Y., Wang, F., Jia, M. & Zhang, S. Parallel hybrid model for mechanical draft counter flow. Appl. Therm. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.07.138 (2017).

Kloppers, J. C. Cooling tower performance evaluation : Merkel Poppe, and e -NTU methods of analysis. J. Eng. Gas Turbine Power 127, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1787504 (2014).

Halasz, B. A general mathematical model of evaporative cooling devices. Revue Générale de Thermique 37(4), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-3159(98)80092-5 (1998).

Xu, Y. et al. Exergetic and economic analyses of a novel modified solar-heat-powered ejection-compression refrigeration cycle comparing with conventional cycle. Energy Convers Manag. 168, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.04.098 (2018).

Moghimi, M., Emadi, M., Ahmadi, P. & Moghadasi, H. 4E analysis and multi-objective optimization of a CCHP cycle based on gas turbine and ejector refrigeration. Appl. Therm. Eng. 141, 516–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.05.075 (2018).

Bejan, A., Tsatsaronis, G. & Moran, M. Thermal design and optimization (John Wiley & Songg, INC, 1996).

Khalilzadeh, S. & Hossein, N. A. Utilization of waste heat of a high-capacity wind turbine in multi effect distillation desalination: Energy, exergy and thermoeconomic analysis. Desalination 439, 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2018.04.010 (2018).

Ahmadzadeh, A., Salimpour, M. R. & Sedaghat, A. Analyse thermique et exergoéconomique d’un nouveau système solaire combinant production d’électricité et de froid par éjecteur. Int. J. Refrig. 83, 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2017.07.015 (2017).

Wang, S. Air conditioning and refrigeration. In CRC handbook of mechanical engineering (ed. Kreith, F.) (CRC Press, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1201/NOE0849397516-10.

Liu, X. et al. Energy, exergy, economic and environmental (4E) analysis of an integrated process combining CO2 capture and storage, an organic Rankine cycle and an absorption refrigeration cycle. Energy Convers Manag. 210, 112738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112738 (2020).

Ghafurian, M. M. & Niazmand, H. New approach for estimating the cooling capacity of the absorption and compression chillers in a trigeneration system. Int. J. Refrig. 140–7007(17), 30480–30482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2017.11.026 (2017).

Xu, Y., Li, Z., Chen, H. & Lv, S. Assessment and optimization of solar absorption-subcooled compression hybrid cooling system for cold storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 180, 115886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115886 (2020).

Rostami, S., Rostamzadeh, H. & Fatehi, R. A new wind turbine driven trigeneration system applicable for humid and windy areas, working with various nano fl uids. J. Clean. Prod. 296, 126579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126579 (2021).

Mohamadi, H., Saeedi, A., Firoozi, Z., Sepasi, S. & Veisi, S. Heliyon Assessment of wind energy potential and economic evaluation of four wind turbine models for the east of Iran. Heliyon 7, e07234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07234 (2021).

Ehyaei, M. A., Ahmadi, A. & Rosen, M. A. Energy, exergy, economic and advanced and extended exergy analyses of a wind turbine. Energy Convers Manag. 183, 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.01.008 (2019).

Diaf, S., Belhamel, M., Haddadi, M. & Louche, A. Technical and economic assessment of hybrid photovoltaic / wind system with battery storage in Corsica island. Energy Policy 36, 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.10.028 (2008).

Ayodele, T. R., Ogunjuyigbe, A. S. O. & Amusan, T. O. Wind power utilization assessment and economic analysis of wind turbines across fifteen locations in the six geographical Zones of Nigeria. J. Clean. Prod. 959–6526(16), 30328–30336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.060 (2016).

Makkeh, S. A., Ahmadi, A., Esmaeilion, F. & Ehyaei, M. A. Energy, exergy and exergoeconomic optimization of a cogeneration system integrated with parabolic trough collector-wind turbine with desalination. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123122 (2020).

Yu, H., Engelkemier, S. & Gençer, E. Process improvements and multi-objective optimization of compressed air energy storage ( CAES ) system. J. Clean. Prod. 335, 130081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130081 (2022).

Bechtler, H., Browne, M. W., Bansal, P. K. & Kecman, V. New approach to dynamic modelling of vapour-compression liquid chillers: Artificial neural networks. Appl. Therm. Eng. 21(9), 941–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-4311(00)00093-4 (2001).

Beghi, A., Cecchinato, L., Cosi, G. & Rampazzo, M. A PSO-based algorithm for optimal multiple chiller systems operation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 32, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.08.008 (2012).

Jain, V., Sachdeva, G., Kachhwaha, S. S. & Patel, B. Thermo-economic and environmental analyses based multi-objective optimization of vapor compression-absorption cascaded refrigeration system using NSGA-II technique. Energy Convers Manag. 113, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.01.056 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Thermodynamic analysis and optimization of pumped thermal–liquid air energy storage (PTLAES). Appl. Energy 332, 120499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120499 (2023).

Alberto Dopazo, J., Fernández-Seara, J., Sieres, J. & Uhía, F. J. Theoretical analysis of a CO2-NH3 cascade refrigeration system for cooling applications at low temperatures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 29, 1577–1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2008.07.006 (2009).

Wu, H. et al. Thermodynamic analysis and operation optimization on a novel heating and cooling integrated system with twin screw compressor and intercooler. Int. J. Refrig. 131, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.07.043 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from University of Zabol with grant No. IR UOZ GR 5425.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Seyedeh Mohadeseh Miri, Mahmood Farzaneh-Gord: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Alireza Hosseinpour: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. Mohit Bajaj, Ievgen Zaitsev: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions