Abstract

In this work, the application of central composite design (CCD) was used to optimise the synthesis of volcanic ash/ rice husk ash-based phosphate geopolymers. The effects of three factors namely, volcanic ash fraction, rice husk ash fraction and phosphoric acid concentration on porosity structure were investigated based on methylene blue index and iodine index as response variables. At optimized conditions of 3.72 g volcanic ash, 1.97 g rice husk ash and 5 M phosphoric acid concentration, desirable porosity structure was attained. The optimized geopolymer and their precursors were characterized by XRF, FTIR and XRD and applied to sequester crystal violet dye (CV) from water. The equilibrium data were described by the Langmuir isotherm with a maximum adsorption density of 14.6 mg/g. Adsorption rate followed pseudo-second-order kinetics. Notably, maximized porosity structure was attained at low acid concentration (5 M), a significant outcome in terms of cost and safety for pilot scale application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geopolymers are amorphous inorganic polymers produced by alkalination of aluminosilicate materials or reaction with phosphoric acid under ambient conditions1. A plethora of aluminosilicate-rich materials have been evaluated for geopolymer development. Naturally occurring minerals of geological origin, such as volcanic ash2,3, pozzolan4, red mud5 and laterite6 are excellent candidates for geopolymer production. Industrial wastes such as solid waste incinerator fly ash7, blast furnace slag8, and fly ash9 are also potential precursors for geopolymer synthesis. Geopolymers are an emerging class of inexpensive low-carbon adsorbents for water treatment10. An excellent adsorbent ought to be recyclable, environmentally friendly, affordable, chemically stable and possess a high surface area (REACH). Geopolymers are particularly excellent adsorbers for dye removal from water.

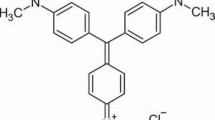

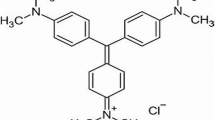

For instance, bentonite-derived geopolymer was synthesized for effective sequestration of crystal violet (CV) dye with a maximum adsorption capacity of 4.34 mg/g11. Elsewhere, Sidjou et al.12 prepared volcanic scoria-based geopolymers for the removal of CV from water and reported a maximum adsorption capacity of 11.06 mg/g. However, acidic functional groups have been reported to diminish CV uptake on an adsorbing material13. Since geopolymer structures possess acidic sites, strategies to optimize the surface chemistry of the geopolymers are required to maximize the adsorption of CV. Geopolymer properties depend on the synthesis conditions such as curing temperature14, type of activator, sodium silicate to sodium hydroxide ratio7 and type and fraction of adjuvant used such as tyre ash15, metal ions16, charcoal powder4, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)17, metakaolin2, chitosan18 and hydrogen peroxide19, among others. Modification of geopolymer porosity structures, textural properties and surface chemistry through the addition of additives provides possibilities for the amelioration of the capability to remove CV by the provision of energetically favourable adsorption sites, screening of unfavourable adsorption sites and improved porosity that reduces tortuosity favouring CV adsorption. For instance, the use of charcoal powder as an adjuvant was reported to increase the adsorption capacity of pozzolan-based geopolymers for CV adsorption both in single and binary solute systems4. In a separate study, the incorporation of 1.0% CS into a metakaolin-based geopolymer resulted in an increased porosity structure of the composite with a concomitant increase in CV adsorption efficiency of about 95%18. The cost and performance of the geopolymer composite depend on the type of adjuvant and the synthesis conditions. While ashes and biochars may stupendously improve the adsorptive characteristics of a geopolymer composite, their preparation may be energy-intensive increasing the cost of production. In addition, their chemical compositions vary considerably, which can unpredictably alter the surface chemistry of the geopolymer composite. Some additives have been shown to improve the textural properties of a geopolymer without altering its characteristics19. However, the interaction of these additives with other synthesis variables, such as alkaline activator concentration, curing time and precursor/activator ratios, has not been documented and is poorly understood.

Evaluation of such interactions may be cumbersome. Response surface methodology (RSM) provides a simple but statistically powerful tool for the optimization of both the adsorbent properties from a set of process conditions12 and the maximum adsorption efficiency from the environmental conditions20. The objective of this work was to optimize the porosity structures and adsorption efficiency of geopolymers using synthesis conditions and environmental factors for the effective removal of CV dye from water.

Materials and methods

Materials

The volcanic ash (VA) was obtained in the Littoral-Cameroon region, Moungo department, commune of Melong, more precisely in the Mbouroukou locality with geographic coordinates 5° 03′ 25″ north, 9°53′ 32″ east. The rice husk ash (RHA) was obtained by burning the rice husk at 600 °C for 60 min. Rice husk was collected from a local rice mill, in the North West region of Cameroon. The CV dye, molecular formula C25H30N3Cl (molecular weight = 407.99, λmax = 590 nm), was purchased from Kermel Chemicals (Cameroon).

Preparation of the geopolymer

The acid-activated volcanic ash/rice husk ash-based geopolymer (GPa) was synthesized according to Tome et al.3: Various masses of volcanic ash (VA) and rice husk ash (RHA) were mixed with phosphoric acid (solid/liquid ratio = 0.45) at various concentration determined by the design of experiment (Table 1). The slurry obtained was then cured at 80 °C for 24 h. After curing for 4 days, the geopolymer obtained was immersed in acetone for 24 h to stop the polycondensation reaction, dried at 80 °C, ground and then sieved to 100 μm. Finally, the samples were washed in distilled water to remove the excess acid.

CCD of experiments

Central composite design for response surface methodology was used to determine the effect of 3 factors (mass of VA, mass of RHA and concentration of phosphoric acid) on the iodine and methylene blue index during the synthesis of geopolymer. The range and levels of the experimental parameters are depicted in Table 1.

Iodine uptake (response 1) and methylene blue uptake (response 2) for the geopolymer synthesised were determined using Eqs. (1) and (2) respectively.

Where Ii and MBi are iodine and methylene blue uptake (mg/g) respectively, B and S are the volumes of thiosulphate solution required for blank and sample titrations, respectively. m (g) is the mass of the adsorbent, M is the concentration (mol/L) of the iodine solute, Ci and Cr (mg/L) are the initial concentration at the equilibrium of the methylene blue, respectively and V (L) is the volume of the solution.

A second-order polynomial response surface model for the fitting of experiment data can be described using Eq. (3)21 :

Where, Y = expected responses, b0, bi, bij and bii were the regression coefficients for intercept, linear, interaction and quadratic terms respectively, whereas xi and xj were the independent factors.

Characterization of the adsorbents

The number of functional groups on the geopolymer surface was studied using a Fourier Transformed Infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (Spectrum Gx, Germany) in the range of 4000 to 400 cm− 1. The mineralogical phase characterization was carried out by quantitative X-ray diffraction. The point zero charge of adsorbents was measured by the pH-drift method detailed by Gomes et al.22.

Sorption procedure for equilibrium and kinetics studies in batch mode

The sorption capacity was determined by contacting 30 mL crystal violet solution of various concentrations (10–100 mg/L) with 0.2 g of GPa on 150 mL Erlenmeyer flasks at pH = 6 and temperature = 25 °C for 60 min. The flasks, tightly stoppered, were shaken on orbital shaker at 100 rpm to ensure equilibrium is reached. The residual concentration of crystal violet was determined using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 590 nm. To determine the effect of the adsorbent dose on the removal of crystal violet, different masses of GPa (0.1–0.6 g) were put in contact with 30 mL of crystal violet solution (Concentration = 60 mg/L, pH = 6 and temperature = 25 °C, 100 rpm) at equilibrium time. The effect of initial pH was determined by varying crystal violet solution pH in the range of 2–12 by adding 0.1 M HCl/NaOH. The amount of crystal violet sorbed onto GPa, Qe (mg/g) and the percentage removal of crystal violet was calculated using Eqs. (4) and (5) respectively:

Where C0 and Ce (mg/L) are, respectively, the initial and equilibrium liquid-phase concentrations of crystal violet; V is the volume of crystal violet solution (L); and m is the weight of GPa (g).

Results and discussion

Design of experiment using CCD

CCD was applied to develop a polynomial regression equation to analyze the relationship between the amounts of iodine and methylene blue adsorbed during GPa synthesis, with the results presented in Table 2. The amount of iodine adsorbed ranged from 254.51 to 704.23 mg/g, and the amount of methylene blue from 14.01 to 22.28 mg/g.

Based on the experimental data, the centred composite design develops regression models to evaluate each response as a function of the process variables12. Model selection was based on the maximum values of R2, Adj-R2 and Pred-R2, and the quadratic model was found to describe both responses. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the correlation coefficients (R2) values denoting the degree of convergence between experimental and predicted data were 0.9064 (Ii) and 0.9382 (MBi); these values were close to unity. Both R2 coefficients were relatively high and in reasonable agreement with the adjusted R2 values of 0.8721 and 0.8826 for iodine and methylene blue removal respectively, indicating that the predicted values were in agreement with the experimental values. The resulting model equations for Ii and MBi are given in Eqs. 6 and 7, respectively.

Analysis of variance

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to further substantiate the suitability of the models. The ANOVA of the iodine index quadratic model listed in Table 3 shows that the model is significant with an F-value of 10.76 and Prob > F of 0.0005. There is therefore a 0.05% chance that variation may occur due to noise. Adequate precision (AP) measures the signal/noise ratio, with a ratio greater than 4 being desirable23. In this case, the ratio of 10.80 for the iodine index indicates a very suitable signal, implying this model can be used to navigate the design space. Prob > F values below 0.05 indicate the significance of the model terms24. In this case, as shown in Table 3, only x3, x12 and x22 are significant terms.

Still, in Table 3, the analysis results for the methylene blue index response during GPa synthesis show that the signal/noise ratio (adequate precision) of 12.21 indicates an adequate signal. The low predicted R2 value implies that several non-significant effects have been included in the model. Thus, the main effect of volcanic ash mass (x1) and its quadratic effect (x12) are significant for the model response. The interactions, x1 × 2 and x1 × 3 are also significant. An adequate precision of 12.21 also indicated an adequate signal, an indication that this model could be used to navigate in the design space.

3D response surface plots

Table 3 shows that phosphoric acid concentration had the strongest effect on the iodine index due to the highest F-value of 11.71, while volcanic ash and rice husk ash masses had weak effects on this response with F-values of 0.33 and 0.18, respectively. The effects of the interactions were inconsistent. Here, the effect of the interaction between volcanic ash mass and phosphoric acid concentration was higher than the other two, with an F-value of 0.45.

The 3D response surface plot of the interaction between volcanic ash mass and phosphoric acid concentration (Fig. 3) shows that the iodine index is highest when the volcanic ash mass is at the ash end of the range and the phosphoric acid concentration is decreased.

For the methylene blue index response, the effect of volcanic ash mass was more significant with an F value of 49.62, while the other two effects, namely rice husk ash mass and phosphoric acid concentration, were similar and inconsistent (Table 3). The effect of the volcanic ash mass/phosphoric acid concentration interaction was greater than that of the volcanic ash/rice husk ash mass interaction, with F values of 10.56 and 7.08, respectively. On the other hand, the effect of the interaction of rice husk ash mass/phosphoric acid concentration was weak and inconsistent with an F-value of 0.04.

The 3D plot representing the variation of the methylene blue index response with the interaction of volcanic ash mass/rice husk ash mass (Fig. 4) shows that this response is maximal in the centre of the domain. However, an increase in the mass of volcanic ash and the mass of rice husk also has a positive effect on the methylene blue index response. For the volcanic ash mass/phosphoric acid concentration interaction at a fixed rice husk ash mass (x2 = 1.5 g) shown in Fig. 5, the observed increase in methylene blue index was due to a simultaneous increase in volcanic ash mass and phosphoric acid concentration.

Responses optimization

When optimizing GPa synthesis, the aim was to maximize iodine and methylene blue indices. By exploiting the response surfaces, optimal conditions during GPa synthesis were obtained for volcanic ash mass = 3.72 g, rice husk ash mass = 1.97 g and phosphoric acid concentration = 5 M with predicted responses of 704.23 mg/g and 21.33 mg/g for iodine and methylene blue indices, respectively, with a desirability of 0.84. As predicted, the experimental values obtained under the same conditions for the iodine index and methylene blue index were 703.88 and 21.82 mg/g, respectively (Table 4).

Feedstocks and geopolymer characterization

The chemical composition of volcanic ash and rice husk ash determined by XRF analysis is given in Table 5. For volcanic ash, SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 and CaO were the main oxides with 41.52, 15.90, 14.74 and 9.67 wt%, respectively. SiO2/Al2O3 ratio (2.61) and SiO2 + Al2O3 sum (57.42) in VA are comparable to those used for geopolymer synthesis with their basic ingredient values within the ranges reported in the literature25,26,27,28. After heat treatment, the RHAs mainly contained SiO2 (80.20 wt%) with a significant amount of K2O (4.95 wt%).

The FTIR spectra of rice husk ash, volcanic ash and geopolymer are shown in Fig. 6. The spectrum of RHA shows bands around 873, 793 and 466 cm− 1 which are attributed to the symmetrical stretching vibration of Si-OH and/or Al-OH, Si-O or Al-O and the bending vibration of Si-O-Si, respectively. The band at 1091 cm− 1 is attributed to asymmetric stretching of the SiO4 unit. For VA and GPa, the absorption bands at 1007 and 1091 cm− 1 are attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of SiO4 units of various connections (Si-O-Si, Si-O-Al and Si-O-Fe)29,30. The characteristic bonds of the O-H group and water molecules are located at 3428 cm− 1, 1646 and 1612 cm− 131,32. The peaks appearing at 572 cm− 1 correspond to the vibration of the Si-O bond32,33 and the peak at 466 cm− 1 represents the vibration of the Si-O-Fe bond3,34.

The XRD spectra of rice husk ash, volcanic ash and geopolymer are shown in Fig. 7. The mineralogical composition of RHA includes calcite, CaCO3 (PDF# 86-2343), cristobalite, SiO2 (PDF#87-2096), diopside sodian, (Ca0.52Na0.29Fe0.10Mg0.09) (Mg0.057 Fe0.14Al0.27Mn0.01Ti0.01) (Si2O6), (PDF#85–1692), albite Na(AlSi3O8), (PDF#71-1156) and anorthoclase, Na0.75K0.25(AlSi3O8) (PDF#89–1459). In VA’s DRX spectrum, albite disordered Na(AlSi3O8), (PDF#20–0572), forsterite ferrous Mg1.641Fe0,359SiO4, (PDF# 88-1993) dolomite CaMg(CO3)2, (PDF#75-1759), anorthoclase, Na0.75K0.25(AlSi3O8) (PDF#89–1459), cristobalite SiO2, (PDF#76–0939), anorthite sodian disordered, (Ca, Na) (Si, Al)4O8, (PDF# 10–0360), diopside manganian, Ca0.87Mn0.19Mg0.94Si2O6), (PDF#83-1834) and labradorite Ca0.65Na0.32(Al1.62Si2.38O8), (PDF# 83-1367) were found. Comparing the diffractograms of volcanic ash to that of optimized geopolymer (GPa), a decrease in the intensity of certain peaks was observed, evidence of the dissolution of minerals during the geopolymerization process35. The presence of a dome between 20° and 40° suggests that the rice husk ash contributed amorphous silica during geopolymerization.

Study of operating parameters for CV dye adsorption by GPa

Effect of initial pH solution

This experiment was carried out at a pH between 2 and 12, a contact time of 60 min, an initial CV concentration of 60 mg/L, an adsorbent dose of 0.2 g and a temperature of 25 °C. The results shown in Fig. 8 indicate that the adsorption rate of CV increased with increasing solution pH. When the solution pH was below the pHpzc (5.4) of the geopolymer material (GPa), protonation of the active binding sites was enhanced by the sharp increase in proton (H+), so the number of active sites became diminished for sorption of CV molecules. On the other hand, at pH above pHpzc, the surface acquired an increasingly negative charge, increasing the adsorption of cationic CV dye molecules due to electrostatic interaction36,37,38,39.

Effect of adsorbent dose

To assess the influence of adsorbent dosage on the percent adsorption of CV by GPa geopolymer, different dosages of GPa (0.1–0.6 g/30 mL) were dispersed in fixed initial CV concentration of 60 mg/L. The effect of the adsorbent dose on crystal violet removal is shown in Fig. 9. From Fig. 9, an increase in the adsorbent mass led to an increase in the percent removal. This was attributed to the increase in the number of active sites available for CV attachment12,36. On the other hand, the decrease in percent removal observed at 0.5 g may be due to agglomeration and overlapping of adsorption sites, resulting in a reduction in the total number of sites accessible to the pollutant40,41,42.

Effect of contact time and initial concentration

Contact time is an essential parameter in adsorption studies as it gives insight of the residence time required for effective removal of contaminants. Figure 10. shows the effect of contact time and initial concentration on the adsorption of crystal violet by GPa. From this figure, it is deduced that the crystal violet has a good affinity for GPa. The shape of the curves is typical of saturation curves, with a slight qualitative and quantitative difference. CV adsorption took place very rapidly from the onset of the experiment, and equilibrium achieved after 60 min. Beyond that, there was almost no appreciable increase in amount adsorbed. These results confirm that CV adsorption on the GPa surface is a spontaneous speed phenomenon in the initial moments, slowing down after 60 min in a state of adsorption saturation. This phenomenon can therefore be divided into two stages: a rapid initial phase due to the availability of the more frequently active sites that were vacant and spontaneously accessible to the CV particles, followed by a slower phase in which the remaining unoccupied surface sites diminish due to the repulsive forces between the solute and the solid phases43,44.

Concerning the influence of initial concentration, the adsorption capacity of crystal violet increased with initial concentration. This was due to the increase in mass gradient, which acts as the driving force to overcome the mass transfer resistance of pollutants. However, the increase in initial concentration can lead to the appearance of a plateau indicating saturation of the support, corresponding to the exhaustion of all the active sites available on the surface of the support45,46.

Adsorption kinetics

The design of adsorption treatment systems requires knowledge of kinetic processes due to the diversity of chemical systems, the nature of the different adsorbents and the different designs of contact systems. For this reason, two liquid-phase adsorption kinetic models, the pseudo-first-order model47 and the pseudo-second-order model48, were used in this study to analyze experimental adsorption kinetic data.

Lagergren’s first-order equation is one of the most widely used for the sorption of a solute from a liquid solution49 and is represented by Eq. 8:

Where qe is the quantity of dye adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), qt is the quantity of dye adsorbed at time t (mg/g), K1 is the first-order reaction rate constant (min− 1).

The expression of the pseudo-second-order model is in the form quoted by Ho and Mckay48 :

Where k2 (g/mg/min) is the rate constant of the pseudo-second-order model.

The curves for the two models are shown in Fig. 11. and the constants obtained from the different models are summarized in Table 6.

The R2 values shown in Table 6 indicate that the pseudo-second-order model best describes the CV adsorption process on GPa. Additionally, the predicted adsorbed quantities at equilibrium calculated by this model were closest to those determined experimentally. Conformity to this model suggests that adsorption of CV onto GPa entails a chemisorption mediated rate-determining step50,51,52.

Adsorption isotherms

The adsorption isotherm is a simple tool, but it plays a very important role in understanding adsorption mechanisms and finding the best adsorbent for large-scale applications. These isotherms provide information on adsorbent/adsorbate affinity and an idea of the binding energy between adsorbate and adsorbent. The equilibrium data were modelled using the two empirical isotherm models, namely the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms.

The Freundlich model uses the exponential distribution of adsorption sites and energies in an adsorption process, assuming that the sites on the adsorbent surface are heterogeneously distributed, and is represented by the following equation53:

Where kF (L/g) and n are Freundlich constants for adsorption capacity and adsorption intensity respectively.

Langmuir’s isothermal model (Eq. (11)) assumes a homogeneous adsorbent surface and monolayer adsorption.

Where: qm is monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g), KL is the Langmuir isotherm constant related to the affinity of the binding sites and energy of adsorption (L/g).

The graph representing the adsorption isotherms is shown in Fig. 12, and the estimated model parameters with the coefficient of determination (R2) for the different models are presented in Table 7. The equilibrium data were best predicted by the Langmuir isotherm. The Langmuir isotherm has been found to be appropriate in describing adsorption phenomenon of CV onto geopolymer composites54. The essential characteristics of the Langmuir isotherm can be expressed in terms of the dimensionless separation parameter RL, which indicates the shape of the isotherm that predicts whether an adsorption system is favourable or unfavourable55. RL is defined by Eq. 1256 :

The RL value for the current experimental data lies between zero and one, indicating favourable adsorption of crystal violet on GPa.

GPa adsorption capacities were compared with those of adsorbents reported in the literature for the removal of crystal violet from water (Table 8).

Conclusion

The preparation conditions for a phosphate geopolymer based on volcanic ash and rice husk ash (i.e. volcanic ash mass, rice husk ash mass and phosphoric acid concentration) were optimized using a three-factor central composite design (CCD). The responses studied were iodine index and methylene blue index, indicators of porosity structure. Under optimized preparation conditions (3.72 g volcanic ash, 1.97 g rice husk ash and 5 M phosphoric acid), the experimental values for iodine number and methylene blue number were 703.88 and 21.82 mg/g, respectively. The adsorbent was characterized and used for crystal violet adsorption from water. Experimental data on the kinetics of the adsorption process conformed to the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, suggesting a chemisorption-mediated rate-determining step. The adsorption equilibrium was further investigated using Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption models. The equilibrium data was best predicted by the Langmuir isotherm with a maximum monolayer density of 14.66 mg/g. The present study concludes that GPa could be used as a low-cost adsorbent and for CV removal in an aqueous solution with favorable synthesis conditions.

Data availability

The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author of this article.

References

Onyango, C. et al. Synthesis of pumice and medical waste incinerator fly ash-based phosphate geopolymers for methylene blue dye adsorption: co-valorization, parameters and mechanism. Mater. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ma00779d (2024).

Shikuku, V. O., Tome, S., Hermann, D. T., Tompsett, G. A. & Timko, M. T. Rapid Adsorption of Cationic Methylene Blue Dye onto Volcanic Ash-metakaolin based geopolymers. Silicon. 14 (15), 9349–9359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-021-01637-9 (2022).

Tome, S., Hermann, D. T., Shikuku, V. O. & Otieno, S. Synthesis, characterization and application of acid and alkaline activated volcanic ash-based geopolymers for adsorptive remotion of cationic and anionic dyes from water. Ceram. Int. 47 (15), 20965–20973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.097 (2021).

Mboka, J. M. et al. Synergistic co-adsorptive removal of crystal violet and chromium(vi) from water by pozzolan-charcoal based geopolymer composites. Mater. Adv. 5, 6234–6247. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ma00408f (2024).

Afolabi, L. O. et al. Red-mud geopolymer composite encapsulated phase change material for thermal comfort in built-sector. Sol. Energy. 181 (February), 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.02.029 (2019).

Tome, S. et al. Efficient sequestration of malachite green in aqueous solution by laterite-rice husk ash-based alkali-activated materials: parameters and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (25), 67278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27138-3 (2023).

Luttah, I., Onunga, D. O., Shikuku, V. O., Otieno, B. & Kowenje, C. O. Removal of endosulfan from water by municipal waste incineration fly ash-based geopolymers: adsorption kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics. Front. Environ. Chem. 4 (March), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvc.2023.1164372 (2023).

Khan, M. I. et al. Effective removal of methylene blue from water using phosphoric acid based geopolymers: synthesis, characterizations and adsorption studies. RSC Adv. 5 (75), 61410–61420. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ra08255b (2015).

Cong, P. & Cheng, Y. Advances in geopolymer materials: a comprehensive review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English Edition). 8 (3), 283–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2021.03.004 (2021).

Elgarahy, A. M. et al. Geopolymers as sustainable eco-friendly materials: classification, synthesis routes, and applications in wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 324 (June), 124631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124631 (2023).

López, J. A., Montao, A. M., González, C. P. & Medina, L. Evaluation of the methyl violet sorption capacity in waters with a bentonite based geopolymer material. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1587(1). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1587/1/012006

Sidjou, A. S. et al. Synthesis of alkali-activated volcanic scoria and rice husk ash based composite materials for adsorptive removal of crystal violet: optimization, kinetics, isotherms and mechanism. Hybrid. Adv. 4 (October), 100113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2023.100113 (2023).

Jacques, M. B. et al. Removal of crystal violet by TiO2 loaded alkali-activated carbon hybrid material from Raphia farinifera fruit kernels: surface chemistry, parameters and mechanisms. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 0123456789, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04988-y (2023).

Owino, E. K., Shikuku, V. O., Nyairo, W. N., Kowenje, C. O. & Otieno, B. Valorization of solid waste incinerator fly ash by geopolymer production for removal of anionic bromocresol green dye from water: kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamics studies. Sustainable Chem. Environ. 3 (July), 100026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scenv.2023.100026 (2023).

Tamaguelon, H. et al. Unary adsorption of sulfonamide antibiotics onto pozzolan-tyre ash based geopolymers: Isotherms, kinetics and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 206, 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2024.05.009 (2024).

Sarkar, C., Basu, J. K. & Samanta, A. N. Experimental and kinetic study of fluoride adsorption by Ni and Zn modified LD slag based geopolymer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 142, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cherd.2018.12.006 (2019).

Yu, Z., Song, W., Li, J. & Li, Q. Improved simultaneous adsorption of Cu(II) and cr(VI) of organic modified metakaolin-based geopolymer. Arab. J. Chem. 13 (3), 4811–4823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.01.001 (2020).

Zhang, J., Ge, Y., Li, Z. & Wang, Y. Facile fabrication of a low-cost and environmentally friendly inorganic-organic composite membrane for aquatic dye removal. J. Environ. Manage. 256 (October 2019), 109969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109969 (2020).

Hermann, D. T. et al. Enhanced performance of Hydrogen Peroxide Modified Pozzolan-based Geopolymer for Abatement of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Medium. Silicon. 14 (10), 5191–5206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-021-01264-4 (2022).

Emily, N. et al. Response Surface Methodology Directed modeling of the Biosorption of progesterone onto acid-activated Moringa Oleifera seed biomass: parameters and mechanisms. Chemosphere. 360, 142457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142457 (2024).

Srivastava, V., Sharma, Y. C. & Sillanpää, M. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of Co(II) removal from synthetic wastewater by adsorption on NiO nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 211, 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2015.07.056 (2015).

Gomes, H. T., Miranda, S. M., Sampaio, M. J., Silva, A. M. T. & Faria, J. L. Activated carbons treated with sulphuric acid: catalysts for catalytic wet peroxide oxidation. Catal. Today. 151 (1–2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.01.017 (2010).

Javadian, H., Ruiz, M. & Sastre, A. M. Response surface methodology based on central composite design for simultaneous adsorption of rare earth elements using nanoporous calcium alginate/carboxymethyl chitosan microbiocomposite powder containing Ni0.2Zn0.2Fe2.6O4 magnetic nanoparticles: batch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 154, 937–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.131 (2020).

Fathinia, M., Khataee, A. R., Zarei, M. & Aber, S. Comparative photocatalytic degradation of two dyes on immobilized TiO 2 nanoparticles: effect of dye molecular structure and response surface approach. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 333 (1–2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2010.09.018 (2010).

Akbal, F. Adsorption of basic dyes from aqueous solution onto pumice powder. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 286, 455–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2005.01.036 (2005).

Fernández-Jiménez, A. & Palomo, A. Characterisation of fly ashes. Potential reactivity as alkaline cements. Fuel. 82 (18), 2259–2265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(03)00194-7 (2003).

Luhar, I. & Luhar, S. A comprehensive review on fly Ash-based Geopolymer. J. Compos. Sci. 6 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs6080219 (2022).

Xu, H. & Van Deventer, J. S. J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. In Int. J. Min. Process. 59, (2000). www.elsevier.nlrlocaterijminpro

Djobo, J. N. Y., Elimbi, A., Tchakouté, H. K. & Kumar, S. Reactivity of volcanic ash in alkaline medium, microstructural and strength characteristics of resulting geopolymers under different synthesis conditions. J. Mater. Sci. 51 (22), 10301–10317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-016-0257-1 (2016).

Djobo, J. N. Y. et al. Synthesis of geopolymer composites from a mixture of volcanic scoria and metakaolin. J. Asian. Ceam. Soc. 2 (4), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jascer.2014.08.003 (2014).

Tchakoute, H. K., Elimbi, A., Mbey, J. A., Sabouang, N., Njopwouo, D. & C. J., & The effect of adding alumina-oxide to metakaolin and volcanic ash on geopolymer products: a comparative study. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 960–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.023 (2012).

Tchakoute, H. K., Elimbi, A., Yanne, E. & Djangang, C. N. Utilization of volcanic ashes for the production of geopolymers cured at ambient temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 38, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.03.010 (2013).

Saikia, B. J. & Parthasarathy, G. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Characterization of Kaolinite from Assam and Meghalaya, Northeastern India. J. Mod. Phys. 01 (04), 206–210. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2010.14031 (2010).

Tchakouté, H. K., Kong, S., Djobo, J. N. Y., Tchadjié, L. N. & Njopwouo, D. A comparative study of two methods to produce geopolymer composites from volcanic scoria and the role of structural water contained in the volcanic scoria on its reactivity. Ceram. Int. 41 (10), 12568–12577. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CERAMINT.2015.06.073 (2015).

Tchakouté, H. K., Rüscher, C. H., Kong, S., Kamseu, E. & Leonelli, C. Thermal behavior of metakaolin-based Geopolymer cements using Sodium Waterglass from Rice Husk Ash and Waste Glass as Alternative activators. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 8 (3), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-016-9653-7 (2017).

Cheruiyot, G. K., Wanyonyi, W. C., Kiplimo, J. J. & Maina, E. N. Adsorption of toxic crystal violet dye using coffee husks: equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics study. Sci. Afr. 5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00116 (2019).

Loulidi, I. et al. Adsorption of Crystal Violet onto an Agricultural Waste Residue: Kinetics, Isotherm, Thermodynamics, and mechanism of Adsorption. Sci. World J. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5873521 (2020).

Mittal, A., Mittal, J., Malviya, A., Kaur, D. & Gupta, V. K. Adsorption of hazardous dye crystal violet from wastewater by waste materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 343 (2), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2009.11.060 (2010).

Wang, X. S. et al. Comparison of basic dye crystal violet removal from aqueous solution by low-cost biosorbents. Sep. Sci. Technol. 43 (14), 3712–3731. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496390802222640 (2008).

Gupta, V. K., Agarwal, S., Ahmad, R., Mirza, A. & Mittal, J. Sequestration of toxic Congo red dye from aqueous solution using ecofriendly guar gum/ activated carbon nanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 158, 1310–1318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.025 (2020).

A Smitha, S., Thirumalisamy, T. & Manonmani, S. Equilibrium and Kinetics Study of Adsorption of Crystal Violet onto the Peel of Cucumis Sativa Fruit from Aqueous Solution. J. Chem. 2012(3), 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/457632 (2011).

Sabna, V., Thampi, S. G. & Chandrakaran, S. Adsorption of crystal violet onto functionalised multi-walled carbon nanotubes: equilibrium and kinetic studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 134, 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.09.018 (2016).

Obayomi, K. S. & Auta, M. Development of microporous activated Aloji clay for adsorption of lead (II) ions from aqueous solution. Heliyon. 5 (11). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02799 (2019).

Saeed, A., Sharif, M. & Iqbal, M. Application potential of grapefruit peel as dye sorbent: kinetics, equilibrium and mechanism of crystal violet adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 179 (1–3), 564–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.041 (2010).

Suhaimi, A. et al. Production of large surface area activated carbon from a mixture of carrot juice pulp and pomegranate peel using microwave radiation-assisted ZnCl2 activation: An optimized removal process and tailored adsorption mechanism of crystal violet dye. Diamond and Related Materials, Volume 130(December 2022), 109456. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2022.109456

Li, S., Li, D., Su, F., Ren, Y. & Qin, G. Uniform surface modification of diatomaceous earth with amorphous manganese oxide and its adsorption characteristics for lead ions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 317, 724–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.08.184 (2014).

Rudzinski, W. & Plazinski, W. Kinetics of solute adsorption at solid/solution interfaces: a theoretical development of the empirical pseudo-first and pseudo-second order kinetic rate equations, based on applying the statistical rate theory of interfacial transport. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110 (33), 16514–16525. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp061779n (2006).

Ho, Y. S. & Mckay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 34 (5), 451–465 (1999).

Tchakounte, A. N., Poumve, H. Z., Kede, C. M. & Dika, J. M. Calcareous-support nanoscale zero-valent iron: New findings on adsorption of cr(VI) in aqueous solution. J. Appl. Surf. Interfaces. 6 (3), 9–17 (2019). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Al-Absi, R. S. Mechanistic understanding of the adsorption and thermodynamic aspects of cationic methylene blue dye onto cellulosic olive stones biomass from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 15928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72996-3 (2020).

Dabagh, A. et al. Adsorption of Crystal Violet from aqueous solution onto eco-friendly native Carpobrotus edulis plant. Mater. Today: Proc. 37, 3980–3986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.349 (2020).

Hamza, W., Dammak, N., Hadjltaief, H. B., Eloussaief, M. & Benzina, M. Sono-assisted adsorption of Cristal Violet dye onto Tunisian Smectite Clay: characterization, kinetics and adsorption isotherms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 163 (June), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.07.021 (2018).

Freundlich, H. About adsorption in solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 57 (1), 385–470 (1907).

Mboka, J. M. et al. Novel superadsorbent from Pozzolan-Charcoal based Geopolymer Composite for the efficient removal of Aqueous Crystal Violet. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 235, 430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-024-07257-4 (2024).

Dada, A., Olalekan, A., ., Olatunya, A. & DADA, O. Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubinin–Radushkevich Isotherms studies of Equilibrium Sorption of Zn 2 + unto Phosphoric Acid Modified Rice Husk. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 3 (1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.9790/5736-0313845 (2012).

Khan, M. A., Wabaidur, S. M., Siddiqui, M. R., Alqadami, A. A. & Khan, A. H. Silico-manganese fumes waste encapsulated cryogenic alginate beads for aqueous environment de-colorization. J. Clean. Prod. 244, 118867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118867 (2020).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tchakounte, A., Lenou, I., Shikuku, V. et al. RSM-CCD design of volcanic ash/ rice husk ash based phosphate geopolymer for crystal violet adsorption: kinetics and isotherms. Sci Rep 14, 29422 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79017-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79017-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sustainable slag-based geopolymers incorporating styrofoam and Moringa leaves ash for mechanical enhancement and crystal violet adsorption

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Mechanical properties of alkali activated geopolymer cement mortar for non vibratory compacted trench backfilling

Scientific Reports (2025)