Abstract

Patellofemoral instability is influenced by morphological factors and associated with compensational alterations in gait pattern. Recent simulation studies investigated the impact of knee morphology on the stability and loading of the patellofemoral joint but neglected the patient-specific gait pattern. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of patient-specific gait pattern on muscle forces and joint loading in individuals with patellofemoral instability. Musculoskeletal simulations with a model including a twelve degrees of freedom knee joint were performed based on three-dimensional motion capture data of 21 individuals with chronic patellofemoral instability and 17 healthy control participants. The patellofemoral instability group walked with a less flexed knee joint and reduced knee flexion and abduction moments compared to the control group, which required less quadriceps muscle forces. Lower quadriceps muscle forces resulted in a reduction of tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint contact forces despite similar walking velocities between both groups. Furthermore, we observed decreased lateralizing patella forces in subjects with patella instability, which could potentially reduce the risk of patella dislocation. Our findings highlight the importance of accounting for the patient-specific gait pattern when analysing knee loads in individuals with patellofemoral instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patellofemoral instability (PFI) is a common knee condition in children and adolescents, which describes inadequate guidance of the patella in the trochlea groove1. It has been shown that ligament properties, bony structure, axial alignment between femur and tibia, as well as neuromuscular factors influence the stability of the patellofemoral joint1,2,3. A lack of stability can further lead to patella dislocations4. Patella dislocations are associated with functional decline and pain3. Untreated PFI and dislocations can result in limitations in physically strenuous activity and cartilage degradation5. Moreover, PFI has been identified as a potential risk factor for patellofemoral arthritis6. Patella dislocations often occur during physical activity, early knee flexion (up to 30 degrees), external rotation of the tibia and contraction of the quadriceps7,8. As these factors arise in gait during the early single stance phase, individuals with PFI alter their gait pattern compared to healthy people9. However, subject-specific gait pattern and its impact on the knee joint loading in patients with PFI have not been investigated yet. A better insight in how the walking pattern of individuals with PFI affect knee joint loads, could help to improve and tailor treatments.

Clinical three-dimensional gait analysis is a well-established method to quantitatively and objectively describe and analyze the gait pattern from a kinematic (joint angles) and kinetic (joint moments) perspective10. Recent studies used this approach to investigate compensational gait strategies in individuals with PFI9,11,12. These studies showed, that individuals with PFI walk with less hip and knee flexion during the entire gait cycle11,13. Further, their internal knee flexion moments during stance were decreased11. In the frontal plane, increased hip adduction angles and abduction moments as well as an increased genu valgum posture was observed in individuals with PFI13,14.

In addition to standard clinical three-dimensional gait analysis, musculoskeletal simulations can be used to increase our insights in the biomechanical pathomechanism of PFI15. Musculoskeletal modelling enables the estimation of internal joint forces and cartilage loading, which cannot be measured in a non-invasive way16,17. Recent research used this approach to investigate the impact of different bone geometries on the patellofemoral stability and loading18. A simulation study showed that during squatting cartilage stress at the patellofemoral joint is sensitive to external rotations of the femur19. Several recent studies used statistical shape models combined with musculoskeletal simulations based on the walking pattern of healthy participants to investigate the influence of patellofemoral geometry on patellofemoral biomechanics18,20,21,22. They found that the geometry can alter patella kinematics (orientation and translation) and patellofemoral loading18. Furthermore, they showed that in knees with a shallow trochlea groove a medial or lateral displacement of the tibial tubercle can lead to a decreased patella stability21 and greater differences in patella position and cartilage contact pressure20. One recent study further found a lower ratio of quadriceps tendon forces to patella ligament forces in Wiberg type III patellas compared to more symmetrical patellas22. Although all the above-mentioned studies increased our insights in patellofemoral biomechanics, a major limitation of these studies is that they mainly used data of healthy individuals to drive their musculoskeletal simulations thereby neglecting patient-specific gait patterns18,19,21,22.

Although it is known that individuals with PFI walk with gait deviations9,11,12, little is known about the impact of the patient-specific walking strategies on tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint loading. A better understanding of altered joint loads in these individuals could support the development of more targeted PFI treatment strategies. To close this gap, we investigated the impact of patient-specific gait patterns in individuals with PFI on the knee joint loading. We hypothesized that individuals with PFI alter their gait pattern to reduce the forces acting on the patella and thus try to reduce the risk of patella luxation.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed three-dimensional motion capture data from a clinical database. Musculoskeletal simulations were performed to investigate how the gait pattern, knee joint loading and patellofemoral contact pressure differ between individuals with PFI and a control group of healthy participants. The ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz (IRB00002556, 34-181 ex 21/22) approved this study. Due to the retrospective nature of this study the requirement of informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz. All methods were performed following relevant regulations and guidelines.

Participants

For the PFI group, inclusion criteria were an age between 10 and 18 years and unilateral recurrent PFI, which was defined as at least three patella dislocations. Subjects with other lower leg injuries or neurological diseases were excluded. Between 2010 and 2020, 256 individuals with PFI were treated at our paediatric orthopaedic centre. Forty-five out of 256 patients experienced three or more patella dislocations and were referred to gait analysis. Twenty-four of these 45 patients were excluded due to bilateral involvement (n = 16), other knee injuries (n = 3), neurological disease (n = 1) or poor data quality (n = 4). Hence, three-dimensional gait analysis data, i.e. marker trajectories and ground reaction forces, of 21 individuals with unilateral recurrent PFI, were included in this study.

As control group, 17 typically developing adolescents, were included. Inclusion criteria for the control group were an age between 10 and 18 years and no injuries at the lower extremities. We ensured that sex and age distribution in the control group matched the participants of the PFI group.

Three-dimensional motion capturing

All gait analysis data were captured in the same laboratory. All participants walked barefoot at self-selected walking speed. Gait analysis data were collected using a ten-camera infrared-based motion capture system (Vicon Motion Systems, Oxford, UK) operated at a sampling rate of 120 Hz. The gait data for the PFI group were collected using the plug-in gait marker set23,24 and for the control group using the modified Cleveland marker set25. Hip joint centres were calculated for all participants based on a modified version of the Harrington equation26, using the pelvis width as input27. Four force plates operated at a sampling rate of 1080 Hz (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA) captured ground reaction forces synchronously to the kinematic trajectories. Force plate threshold was set to 15 N vertical force and gait events were detected automatically for each trial. Trials with no full foot contact solely on one force plate were excluded.

Musculoskeletal simulation

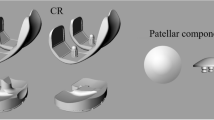

We scaled a generic OpenSim model developed by Lenhart et al.28 to the anthropometry of each participant using the three dimensional motion capturing data29. The same anatomical markers were used to scale the model to the anthropometry of each individuum. The model included 44 muscle–tendon actuators encompassing hip, knee and ankle joint muscles, 14 ligament bundles designed as nonlinear springs, a six degrees of freedom tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint as well as cartilage surfaces for the tibiofemoral and the patellofemoral joint28. The additional degrees of freedom at the knee joint facilitate the computation of secondary knee kinematics, including tibiofemoral abduction and rotation, as well as patellofemoral translation and rotation along the three anatomical axes. Due to a limited number of markers on the foot, the metatarsophalangeal joint and the subtalar joint were locked in each model. Ankle joint plantar-/dorsiflexion remained unlocked in all models. The maximum isometric muscle forces were scaled according to the squared body height30.

We calculated joint angles, external joint moments, muscle forces, joint contact forces and patellofemoral contact pressures. Musculoskeletal simulations were performed based on each participant’s scaled model and the corresponding gait data (Fig. 1). Primary kinematics, such as pelvis motion, hip flexion, hip abduction, hip internal/external rotation, knee flexion, and ankle flexion, were calculated by minimizing the weighted sum of squared differences between the experimental and model marker positions. Additionally, external joint moments were computed using inverse dynamics. The concurrent optimisation of muscle activations and kinematics (COMAK) routine31 was used to concurrently solve the model for muscle activation and secondary knee kinematics. This routine concurrently resolves secondary knee kinematics by minimizing the weighted sum of squared muscle activations and contact energy. Utilizing these outcomes, joint reaction loads were subsequently calculated32. Cartilage contact pressures were calculated using a non-linear elastic foundation model, predicated on the penetration depth between overlapping cartilage surface meshes33,34,35. A uniform cartilage thickness of 3 mm on each surface (6 mm total thickness at the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint) was assumed28,36. Elastic modulus and Poisson-ratio for the cartilage were set to 5 MPa and 0.45, respectively37,38. Maximum marker errors for the inverse kinematic calculations were below OpenSim’s best practice recommendations for all participants39.

Schematic representation of the simulation workflow. Gait analysis data and a generic model served as input data. The generic model was scaled in height, weight and maximum isometric muscle force for each subject. Concurrent optimisation of muscle activations and kinematics routine was used to estimate joint kinematics, joint kinetics and muscle forces. Further joint contact forces and patella cartilage pressure were calculated.

Data analysis

We time normalized each gait cycle to 101 time points (0–100% gait cycle). Ground reaction forces, external moments, contact forces and contact pressure were normalized to the body weight (BW = body mass × g) of each participant. At least five gait cycles were processed and averaged for each participant. Discrete parameters were calculated in prior to averaging curves and separately averaged. Statistical analysis for discrete parameters was performed using SPSS v27 (IBM, New York, USA) and Matlab (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). To statistically compare the waveforms between the PFI and control group we used Statistical parametric mapping40, i.e. SPM1D package for Matlab (http://www.spm1d.org).

Gait kinematic and knee joint loading waveforms in the sagittal, frontal and transversal planes as well as estimated rectus femoris, vastus medialis and vastus lateralis muscle force waveforms were compared between the PFI and control group. As patella dislocations happen in a comparable pattern as at the beginning of single supported stance phase (knee flexion up to 30 degrees and contraction of the quadriceps), we additionally investigated the maximum tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint forces as well as the patellofemoral cartilage pressure at that time point.

To compare discrete parameters such as demographic data, spatiotemporal gait parameters, and the maximum knee joint contact forces and patellofemoral contact pressure at the beginning of the single supported stance phase we used the following procedure. Initially a Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check for normal distribution per goup41. If data was normally distributed we used independent t-tests for comparison, otherwise Mann–Whitney U tests42,43. We calculated Cohen’s d to estimate the effect size44.

To compare the ground reaction force, joint kinematics, external moments, knee joint contact forces and contact pressure waveforms between individuals with PFI and the control group we checked for normal distribution of the waveforms using the normality test provided within the SPM1D package. For normally distributed data we used the parametric version of the two-tailed t-test, for non-parametric data the nonparametric version. Alpha level was set to 0.05. To address for multiple testing we used Bonferroni corrections on different parameter levels as follows45. For the comparison of patellofemoral cartilage pressure waveforms between both groups resulting p-values were correct for three family-wise comparisons (peak pressure, mean pressure, pressure area). Further we corrected the comparisons for the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint contact force waveforms separately for three family-wise comparisons (vertical, anterior–posterior and medio-lateral forces). For the maximum value of joint contact forces and maximum values of patellofemoral cartilage pressure in the first 30 percent of stance phase resulting p-values were correct in accordance with the corresponding waveforms for three family-wise comparisons (vertical, anterior–posterior, medio-lateral tibiofemoral force, vertical, anterior–posterior, medio-lateral patellofemoral force, peak pressure, mean pressure, and pressure area).

Results

The PFI group and control group showed no significant differences in age, sex, height, body weight and body-mass-index (Table 1). Radiographic measurements were available for 20 subjects of the PFI group. The PFI group presented an average Caton-Deschamps index of 1.20 ± 0.14, distance between the tibial tuberosity and the trochlea groove of 15.6 ± 3.1 mm, femoral anteversion of 24.5 ± 9.7 degrees, and tibial torsion of 34.6 ± 8.0 degrees. In regards to trochlear dysplasia, the participants were classified according to the Dejour classification as follows: A (n = 7), B (n = 5), C (n = 6), and D (n = 2). Cadence, stride length, step width and gait speed normalized to the leg length did not significantly differ between both groups. Compared to the control group, the PFI group walked with longer stance phase and shorter swing phase. Double supported stance phases, the loading response and the pre-swing phase were significantly longer and the single stance phase shorter in the PFI group compared to the control group.

Ground reaction forces

Mediolateral ground reaction forces were significantly lower in individuals with PFI compared to healthy controls, whereas vertical and anterior–posterior ground reaction forces did not differ between both groups (Supplementary information 1).

Kinematics

The PFI group walked with lower knee flexion angles during loading response and swing phase. Further, the PFI group walked with lower pelvis and hip abduction at the end of the stance phase, an increased hip internal rotation and knee external rotation (Fig. 2).

Kinematics. The blue and black line represent the mean and one SD for the PFI and the control group, respectively. Horizontal grey bars at the top represent significant differences identified via statistical parametric mapping (SPM) between both groups. A superscript 1 beside the title symbols non-parametric waveform distribution and therefore use of non-parametric version of SPM.

Kinetics

The PFI group walked with a significant lower knee flexion moment at loading response compared to the control group. In the frontal plane, the PFI group displayed lower hip abduction and internal rotation moment and lower knee abduction moment compared to the control group. Frontal plane moments showed a larger standard deviation during the stance phase in the individuals with PFI (Fig. 3). The PFI group showed decreased joint power in loading response and midstance, as well as in late swing phase.

Kinetics. The blue and black line represent the mean and one SD for the PFI and the control group, respectively. Horizontal grey bars at the top represent significant differences identified via statistical parametric mapping (SPM) between both groups. A superscript 1 beside the title symbols non-parametric waveform distribution and therefore use of non-parametric version of SPM. BW, body weight.

Muscle forces

The PFI group walked with significant lower rectus femoris, vastus medialis and vastus lateralis muscle force in loading response (Fig. 4). Further, they walked with more vastus medialis muscle force in early swing phase.

Muscle forces. The blue and black line represent the mean and one SD for the PFI and the control group, respectively. Horizontal grey bars at the top represent significant differences identified via statistical parametric mapping (SPM) between both groups. A superscript 1 beside the title symbols non-parametric waveform distribution and therefore use of non-parametric version of SPM. BW, body weight.

Joint contact forces and patella cartilage pressure

The PFI group showed lower tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint contact forces in the loading response phase (Fig. 5 and Supplementary information 2). Additionally, the PFI group walked with higher patellofemoral joint contact forces at the beginning of swing phase. Maximum and mean patellofemoral cartilage pressures as well as contact area during the loading response phase tends to be lower in the PFI compared to the control group (no significant difference) (Fig. 5).

Patellofemoral joint contact forces as well as patellofemoral cartilage pressure and contact area. The blue and black line represent the mean and one standard deviation for the PFI and the control group, respectively. Horizontal grey bars at the top represent significant differences identified via statistical parametric mapping (SPM) between both groups. A superscript 1 beside the title symbols non-parametric waveform distribution and therefore use of non-parametric version of SPM. BW, body weight; PF, patellofemoral.

Maximum contact forces and maximum patellofemoral contact pressure

The PFI group showed lower maximum forces and maximum pressures, as well as a lower maximum contact area, compared to the control group during the first 30 percent of the stance phase (loading response phase and mid stance phase) (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of altered walking patterns in adolescents with PFI on knee joint loading. Individuals with PFI displayed differences in their gait pattern compared to a typically developing control group. More specifically, individuals with PFI presented altered gait kinematics and kinetics that resulted in a reduction of the quadriceps muscle force in loading response. Unloading of the quadriceps muscle led to a reduction of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint contact forces. In agreement with our hypothesis the patient-specific gait pattern reduced medial–lateral PF contact forces during the first 30 percent of the gait cycle. Interestingly, even though our simulations estimated lower maximum patellofemoral cartilage pressure during the first 30 percent of gait cycle in the PFI group, we found no significant differences between groups for this parameter in the waveforms.

The PFI group walked with a longer stance phase, longer double supported stance phase and shorter single stance phase compared to the control group. An increase in double support can provide more stability, as it allows to adjust gait and correct deviations46. This supports the hypothesis that individuals with PFI alter their gait due to a feeling of instability and use the double supported phases to support the affected leg as long as possible. Another reason, especially for prolongation of loading response phase, might be the longer time for load shifting between legs. In loading response excentric knee flexion is used for shock absorbing47. Longer loading response duration could allow to reduce the use of the knee joint flexion for damping and therefore lower knee joint angles. This consideration is supported by the observed significantly lower knee power in loading response phase in our individuals with PFI compared to the control group (Fig. 3).

The PFI group walked with less knee flexion during loading response compared to the control group. A previous study showed a relationship between reduced knee flexion and decreased dorsiflexion (i.e. plantarflexion/knee extension couple) in individuals with PFI11. This relationship is often called the plantarflexion/knee-extension coupling and is thought to increase the stability of the knee joint, despite lower quadriceps muscle activity, by pulling back the tibia via soleus muscle activity48. In contrast to previous findings, we found no significant difference in ankle kinematics in the PFI group compared to the control group11.

The PFI group walked with internal hip rotation and external rotation of the tibia compared to the control group. This is a pattern frequently seen in individuals with PFI9. Further, it is in coherence with the increased femoral anteversion (24.5° ± 9.7°) and tibial torsion (34.6° ± 8.0°) in our PFI group. External tibia rotation is a predisposing factor for patella dislocation8. Furthermore, internal rotation of the femur affects the Q-angle and thus lateralize the direction of rectus femoris muscle force49. Therefore, deviation in hip and knee rotation might be part of the primary pathology and not a secondary compensation of gait50. Future research, focussing on gait retraining, should investigate the impact of treating gait pattern in the transversal plane on the stability of the patellofemoral joint51,52.

The PFI group walked with reduced external knee flexion moments during the loading response phase compared to the control group. The knee flexion angle alters the lever arm between the knee joint and ground reaction force53. Hence, the less flexed knee might be partially responsible for the reduced knee flexion moment. Lower knee moments reduce the necessity of high knee extensor muscle forces and therefore lead to an unloading of the knee joint.

In the frontal plane, the PFI group walked with reduced hip and knee joint moments. This might be caused by compensatory trunk kinematics which alters the direction of ground reaction force and thus reduce the frontal plane moments54. Though not included in the scope of this project, future research could focus on the impact of trunk movement in gait pattern of individuals with patellofemoral instability. The observed combination of differences in joint kinematics and medio-lateral ground reaction force might explain the reduced knee and hip abduction moments.

Musculoskeletal simulations showed that gluteus maximus compensates a lack of gluteus medius strength to generate hip abduction moment55. Additionally to the hip abduction moment, the gluteus maximus produces a hip extension moment, which is compensated by the rectus femoris and leads to an increased co-contraction and therefore joint loads at the hip and knee joint56. Individuals with PFI and a weak gluteus medius57 could avoid this mechanism with an altered gait pattern which reduces the hip abduction moment. Thus, the observed reduction in hip abduction moments could be a compensatory mechanism of individuals with PFI, to unload the knee joint. Contrary to our findings, one study found higher abduction knee moments in individuals with PFI12.

We observed a reduction of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint contact forces in loading response in our participants with PFI compared to the control group. The PFI group walked with altered gait kinematics and kinetics (i.e. reduced knee flexion angle and moment, reduced hip abduction moment), which led to reduced quadriceps muscle forces. Walking with a less flexed knee joint to reduce quadriceps muscle force is called quadriceps avoidance pattern11 and is also known from other pathologies, e.g. people with patellofemoral pain syndrom58. This quadriceps avoidance pattern reduces the pull of the quadriceps muscle on the patella and consequently decreases the compressional force acting on the knee joint59.

Differences in joint kinematics and kinetics in our subjects with PFI lowered lateral patellofemoral contact force. A lateralizing force, especially in combination with a disadvantageous geometry (e.g. a shallow trochlea) increases the probability of a patella dislocation60. Besides that, increased femoral anteversion and hip internal rotation, can lead to an increased lateralizing force due to altered muscle lines of action of the rectus femoris and the vastus lateralis muscles49. A mechanism relevant to individuals with PFI, as higher femoral anteversion is common in those subjects61 and was also observed in our cohort.

Another reason for the quadriceps avoidance gait pattern could be pain. At six months after the last dislocation, a study showed load-dependent pain in individuals with PFI (39% of patients suffered from pain while running, minimal pain was reported while sedentary activities)62. Since the impact and load during walking is somewhere between running and sedentary activity, we expect little pain in our PFI group. A prospective study showing similar gait pattern in individuals with PFI compared to our PFI group reported no pain in their cohort and thus no relation between pain and walking strategy11. Future research should focus on a comprehensive pain screening to evaluate the relationship between gait pattern and pain for PFI in detail.

Patellofemoral cartilage pressure waveforms showed no significant differences in pressures in the PFI compared to the control group. The PFI group walked with a reduced knee flexion in loading response and thus reduced contact area between patella and trochlea groove63. The calculation of contact pressure depends on the applied force and the area. Thus, a reduction of the contact area might explain why we did not find significant differences in cartilage pressure in the waveforms despite the lower joint contact force. In contrast, the maximum pressure values during the first 30 percent of gait cycle showed significant lower pressures in the PFI group, and thus showed a reduced patella cartilage loading in individuals with PFI.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, we have no comprehensive information about perceived pain, exact number of dislocations and subjective assessment of knee stability. Therefore, we are limited in our interpretation and we do not know if gait pattern and knee contact forces were influenced by these factors. It is possible that some of the subjects suffered from pain and therefore altered their gait pattern to unload the knee joint3. A prospective study, however did not find a relationship between pain and gait pattern in individuals with PFI11. Second, metatarsal and subtalar joints were locked in all models, which could have slightly altered joint kinematics and joint loading in our simulations. This is a common procedure in musculoskeletal simulations, when only two markers are available at the foot segment64,65,66. Another limitation of the present study is, that the gait analysis data of the PFI group and the control group were collected with two different marker sets. This limitation is inherent to the retrospective nature of this study. However, a previous study demonstrated that the marker model has negligible impact on the simulation results67, and we therefore do not expect a relevant impact on our findings. Further, PFI is highly influenced by the bony geometry, e.g. shape of the trochlea groove1,2,3. Deviations in joint geometry can lead to changes in the contact area20. As our musculoskeletal models were all based on the same bony geometry our estimated pressures might not represent the real pressures. Our study, however enabled us to quantify differences in knee loads and patellofemoral cartilage pressure solely caused by the patient-specific gait pattern. Future research based on medical-imaging informed models could focus on the combined impact of patient-specific gait pattern and bone geometry on knee joint loads in people with PFI.

Conclusion

This study showed how individuals with PFI alter their gait pattern to reduce knee joint loads. Compared to healthy controls, our individuals with PFI walked with less knee flexion during the stance phase and therefore required less quadriceps muscle forces. Lower quadriceps muscle forces resulted in a reduction of tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint forces. Especially the decreased lateralizing force on the patella could potentially decrease the risk of patella dislocation and might explain why people with PFI walk with an altered gait pattern. Our findings highlight the importance of accounting for the patient-specific gait pattern when analysing knee loads in people with PFI.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Vetrano, M. et al. I.S.Mu.L.T. first-time patellar dislocation guidelines. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 7, 1 (2019).

Fox, A., Wanivenhaus, F. & Rodeo, S. The basic science of the patella: Structure, composition, and function. J. Knee Surg. 25, 127–142 (2012).

Frosch, S. et al. Die therapie der patellaluxation: eine systematische literaturanalyse. Zeitschr. Orthopädie Unfallchirurgie 149, 630–645 (2011).

Hasler, C. C. & Studer, D. Patella instability in children and adolescents. EFORT Open Rev. 1, 160–166 (2016).

Kader, D. F., Matar, H. E. & Caplan, N. Patellofemoral joint instability: A review of current concepts. jot 6, 145 (2016).

Sanders, T. L. et al. Incidence of first-time lateral patellar dislocation: A 21-year population-based study. Sports Health: A Multidiscipl. Approach 10, 146–151 (2018).

Höhne, S. et al. Patella dislocation in children and adolescents. Zeitschr. Orthopädie Unfallchirurgie 155, 169–176 (2017).

Dewan, V. et al. When does the patella dislocate? A systematic review of biomechanical & kinematic studies. J. Orthopaed. 20, 70–77 (2020).

Habersack, A. et al. Gait pathology in subjects with patellofemoral instability: A systematic review. IJERPH 19, 10491 (2022).

Baker, R. Gait analysis methods in rehabilitation. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 3, 4 (2006).

Camathias, C. et al. Recurrent patellar dislocations in adolescents result in decreased knee flexion during the entire gait cycle. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 2053–2066 (2020).

Ammann, E. et al. Elevated hip adduction angles and abduction moments in the gait of adolescents with recurrent patellar dislocation. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-022-04703-y (2022).

Ammann, E. et al. Trochleoplasty improves knee flexion angles and quadriceps function during gait only if performed bilaterally. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 2067–2076 (2020).

Lucas, K. C. H., Jacobs, C., Lattermann, C. & Noehren, B. Gait deviations and muscle strength deficits in subjects with patellar instability. The Knee 27, 1285–1290 (2020).

Wheatley, M. G. A., Rainbow, M. J. & Clouthier, A. L. Patellofemoral mechanics: A review of pathomechanics and research approaches. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 13, 326–337 (2020).

Seth, A. et al. OpenSim: Simulating musculoskeletal dynamics and neuromuscular control to study human and animal movement. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006223 (2018).

Smith, C. R., Won Choi, K., Negrut, D. & Thelen, D. G. Efficient computation of cartilage contact pressures within dynamic simulations of movement. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Visual. 6, 491–498 (2018).

Clouthier, A. L. et al. The effect of articular geometry features identified using statistical shape modelling on knee biomechanics. Med. Eng. Phys. 66, 47–55 (2019).

Besier, T. F., Gold, G. E., Delp, S. L., Fredericson, M. & Beaupré, G. S. The influence of femoral internal and external rotation on cartilage stresses within the patellofemoral joint. J. Orthopaed. Res. 26, 1627–1635 (2008).

Clouthier, A. L. et al. Influence of articular geometry and tibial tubercle location on patellofemoral kinematics and contact mechanics. J. Appl. Biomech. 38, 58–66 (2022).

Clouthier, A. L., Borschneck, D., Thelen, D. G., Deluzio, K. J. & Rainbow, M. J. Relationship between lateral patellar stability and tibial tubercle location for varying patellofemoral geometries. J. Biomech. Eng. 141, 12 (2019).

Wheatley, M. G. A., Clouthier, A. L., Thelen, D. G. & Rainbow, M. J. Patella Apex Influences Patellar Ligament Forces and Ratio. J. Biomech. Engi. 143, 8 (2021).

Davis, R. B., Õunpuu, S., Tyburski, D. & Gage, J. R. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum. Movement Sci. 10, 575–587 (1991).

Kadaba, M. P., Ramakrishnan, H. K. & Wootten, M. E. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J. Orthopaed. Res. 8, 383–392 (1990).

Svoboda, B. & Kranzl, A. A study of the reproducibility of the marker application of the Cleveland Clinic Marker Set including the Plug-In Gait Upper Body Model in clinical gait analysis. Gait Posture 36, S62–S63 (2012).

Harrington, M. E., Zavatsky, A. B., Lawson, S. E. M., Yuan, Z. & Theologis, T. N. Prediction of the hip joint centre in adults, children, and patients with cerebral palsy based on magnetic resonance imaging. J. Biomech. 40, 595–602 (2007).

Kainz, H., Carty, C. P., Modenese, L., Boyd, R. N. & Lloyd, D. G. Estimation of the hip joint centre in human motion analysis: A systematic review. Clin. Biomech. 30, 319–329 (2015).

Lenhart, R. L., Kaiser, J., Smith, C. R. & Thelen, D. G. Prediction and validation of load-dependent behavior of the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints during movement. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 43, 2675–2685 (2015).

Kainz, H. et al. Accuracy and reliability of marker-based approaches to scale the pelvis, thigh, and shank segments in musculoskeletal models. J. Appl. Biomech. 33, 354–360 (2017).

Steele, K. M., Van Der Krogt, M. M., Schwartz, M. H. & Delp, S. L. How much muscle strength is required to walk in a crouch gait?. J. Biomech. 45, 2564–2569 (2012).

Smith, C., Lenhart, R., Kaiser, J., Vignos, M. & Thelen, D. Influence of ligament properties on tibiofemoral mechanics in walking. J. Knee Surg. 29, 099–106 (2015).

Steele, K. M., DeMers, M. S., Schwartz, M. H. & Delp, S. L. Compressive tibiofemoral force during crouch gait. Gait Posture 35, 556–560 (2012).

Bei, Y. & Fregly, B. J. Multibody dynamic simulation of knee contact mechanics. Med. Eng. Phys. 26, 777–789 (2004).

Guess, T. M., Liu, H., Bhashyam, S. & Thiagarajan, G. A multibody knee model with discrete cartilage prediction of tibio-femoral contact mechanics. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 16, 256–270 (2013).

Thelen, D. G., Won Choi, K. & Schmitz, A. M. Co-Simulation of neuromuscular dynamics and knee mechanics during human walking. J. Biomech. Eng. 136, 2 (2014).

Segal, N. A. et al. Baseline articular contact stress levels predict incident symptomatic knee osteoarthritis development in the MOST cohort. J. Orthopaed. Res. 27, 1562–1568 (2009).

Blankevoort, L. & Huiskes, R. Ligament-bone interaction in a three-dimensional model of the knee. J. Biomech. Eng. 113, 263–269 (1991).

Caruntu, D. I. & Hefzy, M. S. 3-D anatomically based dynamic modeling of the human knee to include tibio-femoral and patello-femoral joints. J. Biomech. Eng. 126, 44–53 (2004).

Hicks, J. L., Uchida, T. K., Seth, A., Rajagopal, A. & Delp, S. L. Is my model good enough? Best practices for verification and validation of musculoskeletal models and simulations of movement. J. Biomech. Eng. 137, 020905 (2015).

Pataky, T. C. One-dimensional statistical parametric mapping in Python. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 15, 295–301 (2012).

Shapiro, S. S. & Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52, 591–611 (1965).

Kim, T. K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 68, 540 (2015).

Mann, H. B. & Whitney, D. R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. (1947).

Cohen, J. Statistic Power Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences (Academic Press, 1969).

Armstrong, R. A. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalm. Physiol. Opt. 34, 502–508 (2014).

Williams, D. S. & Martin, A. E. Gait modification when decreasing double support percentage. J. Biomech. 92, 76–83 (2019).

Shah, K., Solan, M. & Dawe, E. The gait cycle and its variations with disease and injury. Orthopaed. Trauma 34, 153–160 (2020).

Brunner, R., Dreher, T., Romkes, J. & Frigo, C. Effects of plantarflexion on pelvis and lower limb kinematics. Gait Posture 28, 150–156 (2008).

Imhoff, F. B. et al. Dynamic Q-angle is increased in patients with chronic patellofemoral instability and correlates positively with femoral torsion. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 29, 1224–1231 (2021).

Schranz, C. et al. Different gait pattern in adolescence with patellofemoral instability. Clin. Biomech. 108, 106067 (2023).

Kainz, H. et al. A framework based on subject-specific musculoskeletal models and Monte Carlo simulations to personalize muscle coordination retraining. Sci. Rep. 14, 3567 (2024).

Diamond, L. E. et al. Feasibility of personalised hip load modification using real-time biofeedback in hip osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 4, 100230 (2022).

Nagano, H., Tatsumi, I., Sarashina, E., Sparrow, W. A. & Begg, R. K. Modelling knee flexion effects on joint power absorption and adduction moment. The Knee 22, 490–493 (2015).

Watelain, E., Dujardin, F., Babier, F., Dubois, D. & Allard, P. Pelvic and lower limb compensatory actions of subjects in an early stage of hip osteoarthritis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 82, 1705–1711 (2001).

Valente, G., Taddei, F. & Jonkers, I. Influence of weak hip abductor muscles on joint contact forces during normal walking: Probabilistic modeling analysis. J. Biomech. 46, 2186–2193 (2013).

Kainz, H., Mindler, G. T. & Kranzl, A. Influence of femoral anteversion angle and neck-shaft angle on muscle forces and joint loading during walking. PLoS One. 18, 1–23 (2023).

Arrebola, L. S. et al. Hip and knee weakness and ankle dorsiflexion restriction in individuals following lateral patellar dislocation: A case-control study. Clin. J. Sport Med. 31, e385–e391 (2021).

Barton, C. J., Levinger, P., Menz, H. B. & Webster, K. E. Kinematic gait characteristics associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A systematic review. Gait Posture 30, 405–416 (2009).

Shelburne, K. B., Torry, M. R. & Pandy, M. G. Muscle, ligament, and joint-contact forces at the knee during walking. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37, 1948–1956 (2005).

Fithian, D. C., Nomura, E. & Arendt, E. Anatomy of patellar dislocation. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 9, 102–111 (2001).

Iacobescu, G., Cirstoiu, C., Cursaru, A., Anghelescu, D. & Stanculescu, D. Correlation between patellar tilt angle, femoral anteversion and tibial tubercle trochlear groove distance measured by computer tomography in patients with non-traumatic recurrent patellar dislocation. Maedica (Bucur) 15, 174–180 (2020).

Atkin, D. M. et al. Characteristics of patients with primary acute lateral patellar dislocation and their recovery within the first 6 months of injury. Am. J. Sports Med. 28, 472–479 (2000).

Besier, T. F., Draper, C. E., Gold, G. E., Beaupré, G. S. & Delp, S. L. Patellofemoral joint contact area increases with knee flexion and weight-bearing. J. Orthop. Res. 23, 345–350 (2005).

Wesseling, M. et al. Botulinum toxin injections minimally affect modelled muscle forces during gait in children with cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 82, 54–60 (2020).

Van Rossom, S. et al. Single-event multilevel surgery, but not botulinum toxin injections normalize joint loading in cerebral palsy patients. Clin. Biomech 76, 105025 (2020).

Kainz, H. & Schwartz, M. H. The importance of a consistent workflow to estimate muscle-tendon lengths based on joint angles from the conventional gait model. Gait Posture 88, 1–9 (2021).

Kainz, H. et al. Joint kinematic calculation based on clinical direct kinematic versus inverse kinematic gait models. J. Biomech. 49, 1658–1669 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support of the Austrian Academy of Sciences for AH, who is a recipient of a DOC Fellowship (25940) at the Department of Orthopaedics and Trauma, Medical University of Graz, and the Institute of Human Movement Science, Sport and Health, University of Graz. Brian Horsak received funding from the Research Promotion Agency of Lower Austria (Gesellschaft für Forschungsförderung NÖ) within the Endowed Professorship for Applied Biomechanics and Rehabilitation Research (SP19-004). Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Initial idea BG, HK, MS; Conceptualisation BG, BH, HK, MS; Data acquisition AH, BG, AK, MS; Analysis BG, BH, AH, CS, HK; Methodology BG, BH, HK, CS; Interpretation BG, BH, AH, AK, CS, HK, MS; Writing original draft BG, BH, HK, MS; Critical revision of final draft all authors; All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guggenberger, B., Horsak, B., Habersack, A. et al. Patient-specific gait pattern in individuals with patellofemoral instability reduces knee joint loads. Sci Rep 14, 28520 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79021-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79021-x