Abstract

The analysis of seismic response in marine engineering structures is pivotal for guaranteeing their seismic safety. Such analyses are intricate due to the complexity of fluid–structure and soil-structure interactions. This paper introduces a unified computational framework for wave motion within a water-saturated seabed-bedrock system, employing the Davidenkov model and a modified Massing rule to characterize the nonlinear properties of the saturated seabed. A comparative analysis is conducted between the nonlinear responses of marine sites subjected to linear and nonlinear free-field inputs, with a specific focus on the seismic response of bridges under seawater-seabed-structure interaction. The study demonstrates that the modulus of a nonlinear saturated seabed diminishes, leading to a decrease in the wave impedance ratio between the saturated seabed and bedrock. Consequently, the reflection and transmission coefficients from the bedrock to the saturated seabed increase, amplifying the seismic response. For deepwater bridges, under harder site conditions, the abutment’s bottom response is largely insensitive to increasing water depth, whereas the shear at the abutment’s base diminishes with increasing water depth. The proposed method is validated through two case studies, with an examination of the impact of saturated sites on the analysis results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the introduction and implementation of the "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" and “Ocean Power” strategies, China has increased the development and use of marine areas, and many marine engineering structures and infrastructure projects are under rapid construction and development. To ensure the safety of these offshore structures under earthquake action, it is necessary to accurately predict the ground motion in the sea area. At present, there are three main types of ground motion prediction, namely, prediction based on ground motion attenuation relationship, theoretical analysis prediction and numerical simulation prediction. For the prediction based on the ground motion attenuation relationship, the records of strong earthquakes at sea are less than those on land. In addition, there is a lack of material parameters and spatial distribution of marine soil layer, so it is difficult to determine the attenuation relationship of marine ground motion. Therefore, in the seismic design of offshore structures, land strong earthquake records are usually selected. However, due to the presence of deep soft sedimentary layers, the seismic attenuation relationships for offshore sites are very different from those for land-based sites1,2. Typically, for theoretical analysis and prediction, relevant researchers have simplified the marine topography to a generic model and used theoretical methods to solve the marine seismic response3,4,5,6,7. However, related results show that this approach is only applicable where suitable topography is available (e.g. horizontal stratigraphic positions) and cannot be directly used to simulate seismic motions in coastal areas with complex topography.

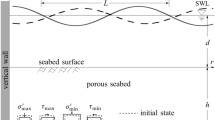

To ensure the seismic safety of offshore engineering structures, accurate analysis, and prediction of their response under potential seismic action is firstly required8,9,10,11,12,13. At present, due to the limitation of underwater shaker equipment, the seismic response analysis of offshore structures by experimental methods is rare. The numerical analysis is a semi-infinite domain seismic wave scattering problem (as shown in Fig. 1), which involves the analysis of the free field of the marine site (providing input to the scattering problem), the analysis of the seawater-saturated seabed-structure interaction, and the artificial boundary conditions of the semi-infinite marine site, which are very complicated.

With the development of computer technology and the maturity of numerical calculation methods, in the past few decades, some researchers began to use numerical simulation methods to solve the problem of ground motion response in complex sea areas. Morency and Tromp14described the propagation of waves in different media based on domain decomposition, and described the interface continuity conditions to solve the discontinuity between different media. Link et al15. simulated the ground motion in Suruga Bay and the results showed that the irregular topography of the sea layer and sea area had a great impact on the amplitude and duration of S-wave tail. Liu et al16. simulated the wave radiation effect in the infinite fluid solid domain of the reef seawater system under appropriate artificial boundary conditions. From above numerical methods, liquid, solid and multi elastic media are analysed by independent solvers, and then connected through data exchange, which is very troublesome. Chen et al17,18. proposed a decoupling simulation technology to simulate the seismic acoustic scattering in the marine area when the seismic wave is incident. The Biot’s theory of saturated porous media and the continuity conditions between different media are extended, and different media (liquid, saturated porous media, solid) are successfully unified in the framework of generalized saturated porous media. In a unified framework, different media can be simulated simultaneously in one solver by assigning corresponding parameters (porosity, wave velocity, density, etc.) to generalized saturated porous media.

Although researchers have used many methods to simulate seismic acoustic scattering in ocean sites, the simulation of ground motion in large-scale three-dimensional sea areas is still limited by computational methods and computer hardware. In addition, three-dimensional ocean models have been proven to simulate seabed surface motion more accurately than one-dimensional/two-dimensional models, especially in complex terrain areas19,20,21. However, in practical simulations, if three-dimensional models are used to simulate seismic acoustic scattering in high spatial resolution sea areas, the demand for computing resources rapidly increases, and traditional computing methods can no longer meet the computational requirements. If we want to improve computational efficiency and fully utilize PC performance, relevant scholars22,23,24 have adopted GPU parallelism, CPU master–slave communication parallelism, and CPU cache communication parallelism to accelerate ground motion simulation of three-dimensional sites. In numerical simulations addressing the fluid–solid coupling problem involving seawater, a saturated seabed, and structural elements, conventional approaches require separate solvers for the fluid acoustic wave equation, the saturated porous medium equation, and the solid fluctuation equation. This method necessitates interface coupling at each time step, which is cumbersome. Currently, there are no established methods or software that efficiently resolve this issue. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an efficient method for coupled seawater-saturated seabed-structure analysis in marine seismic engineering that considers the non-linearity of the seabed and reveals the mechanism of seabed liquefaction instability and the disaster mode of marine structures under strong seismic effects.

When the intensity of motion is high, there may be uplift or sliding between the soil and foundation and nonlinear effects from the gaps between the soil and the structure, and the soil near the building foundation (i.e. near-field soil) may behave in an inelastic range. For the analysis of non-linear seismic response of marine sites, either equivalent linearization analysis methods25,26or time-domain non-linear analysis methods17,18,27,28,29,30can be used. It is generally considered that the equivalent linearization method is suitable for weak nonlinearities, and for strong nonlinearities, the time-domain nonlinear analysis method is appropriate. When time-domain non-linear methods are used to analyse the seismic response of a site, a free-field analysis of the horizontally stratified site needs to be carried out first as an input to the boundary. Currently, the transfer matrix method7,31,32is generally used for free field analysis, which is suitable for linear or equivalently linearized situations, and can consider oblique incidence of seismic waves; a numerical finite element analysis method33,34,35 can also be used to convert the two-dimensional free field analysis to one-dimensional analysis according to Snell’s law, using numerical methods to achieve a one-dimensional analysis, and then extrapolating the one-dimensional wave field to two- and three-dimensional according to the apparent velocity This extrapolation is only suitable for the linear case where the wave velocity is constant. Therefore, if the non-linear free field is solved numerically, only a one-dimensional free field, i.e. the vertical incidence case, can be obtained. When considering the non-linearity of the saturated seabed, it is theoretically necessary to use the same instanton model for the free field calculations as for the inner domain calculations, and it is worth discussing the impact on the results if the instanton structure does not agree with that of the inner domain analysis.

In this paper, based on the free field analysis of marine sites and a unified computational framework for coupled fluid–structure problems in earthquake engineering17,18,36,37,38, the nonlinearity of the saturated seabed is first considered, the nonlinear response characteristics of sea sites are analysed, and the effects of using linear and nonlinear free fields on the results are discussed. The dynamic response of the marine site and the seawater-seabed-structure system under seismic action is further analysed, and the differences in the response between the linear and non-linear seabed cases are compared to provide a theoretical basis and analytical means for the seismic design of marine engineering structures. The effect of water-site-structure coupling on the seismic response of the bridge is investigated by varying the water depth and soil condition.

In the following, I briefly introduce the strategy of the generalized saturated porous media framework in Basic theory. In Validations of the proposed methodology, the numerical techniques adopted in the present code are described, and a 3D field with the SV-wave input is used for the example analysis of the code. After that, I based on the unified calculation framework for wave motion in a water-saturated seabed-bedrock system, using the Davidenkov model and modified Masing rule to describe the nonlinear characteristics of the saturated seabed and the nonlinear response of marine sites under the input of linear free field and nonlinear free field is analysed comparatively. The conclusions are presented in Results analysis.

Basic theory

In this section, I briefly introduce the FEM based on unified computational framework for simulating wave motion in water saturated seabed-bedrock system and the algorithms adopted in the proposed code. The details of theories can be found in Chen et al17,18,36. and Lv and Chen37,38.

Theoretically, solid and fluid media are special cases of saturated porous media with porosity of 0 and 1, respectively, and the coupling between different media can all be described in the generalized saturated porous media system.

Basic differential equation

According to Biot porous medium theory39,40, for saturated porous media, the solid phase equilibrium Equation

Liquid-phase equilibrium Equation for saturated porous media

Compatibility Equation (considering initial pore pressure and initial body strain as zero)

where Ls and Lw are differential operator matrices, \({\mathbf{\sigma^{\prime}}}\) is the solid effective stress vector, τ is the average pore pressure, which is positive under tension. P is the pore water pressure, which is positive under compression. U and u respectively represent the displacement vectors of the liquid and solid phase, \(\dot{U}\) and \(\dot{u}\) are the velocity vectors, and \(\ddot{U}\) and \(\ddot{u}\) are acceleration vectors. ρs and ρw are the density of the solid and liquid phase, respectively. β is the porosity, \(b = {{\beta^{2} \mu_{0} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\beta^{2} \mu_{0} } k}} \right. \kern-0pt} k}_{0}\), k0 is fluid permeability coefficient, μ0 is the kinematic viscosity coefficient, Ew is the bulk modulus of the fluid, es and ew respectively represent the volume strain of the solid and liquid phase.

The above Equation can be degraded to the ideal fluid Equation when the pore ratio β = 1, and to the elastic fluctuation Equation when the pore ratio β = 0. Therefore, fluids, elastic solids and saturated porous media can be described by the generalized saturated porous Equation in a unified way, which extend the porosity 0 < β < 1 for the saturated porous media to 0 ≤ β ≤ 1. Here, only the material parameters are different. Therefore, the seismic wave propagation problem in marine sites can be described by the generalized saturated porous Equation.

Discretization and solution of motion equations

The Eqs. (1) and (2) are discretized by the Galerkin method, and considering the compatibility Eq. (3) and the boundary conditions, the decoupling motion equilibrium Equation of any node i can be obtained as:

where \({M}_{{{\text{s}}i}}\) and \({M}_{wi}\) represent the mass matrix of the solid phase and the mass matrix of the liquid phase respectively.\({F}_{i}^{{\text{s}}}\) and \({F}_{i}^{{\text{w}}}\) represent the vectors of solid and liquid constitutive forces respectively, and the Davidenkov model is used in this paper to consider the non-linearity of the solid phase, as described in Nonlinear constitutive model for saturated soil based on a Davidenkov skeleton curve. \({T}_{i}^{{\text{s}}}\) and \({T}_{i}^{w}\) respectively represent the vectors of solid and liquid viscosity resistances concentrated at the node,\({S}_{i}^{{\text{s}}}\) and \({S}_{i}^{w}\) represent the vectors of solid and liquid interfacial forces, respectively. Since the seismic response is input through the free field displacement of the boundary node, \({f}_{i}^{{\text{s}}}\) and \({f}_{i}^{{\text{w}}}\) represent the vectors of solid and liquid external forces other than the seismic load.

Internal node

For the internal nodes, \({S}_{i}^{{\text{s}}}\) and \({S}_{i}^{w}\) are both zero. If the constitutive relationship is given, the Eqs. (4) and (5) can be solved by time-step integration, which can be written as follows:

where \({u}_{i}^{{\left( {p - 1} \right)}}\), \({u}_{i}^{p}\) and \({u}_{i}^{{\left( {p + 1} \right)}}\) denote the solid phase displacement vectors of node i at (p-1), p ,and (p + 1) moments respectively; \({U}_{i}^{(p - 1)}\), \({U}_{i}^{p}\) and \({U}_{i}^{(p + 1)}\) are the liquid phase displacement vectors of node i at the corresponding moments; Δt represents the time step; \(m_{i}^{s}\) and \(m_{i}^{{\text{w}}}\) represent the solid and liquid phase masses concentrated at node i, respectively.

Interfacial node

Using the concept of isolator, and performing time-step integration on Eqs. (4) and (5) at time p + 1, and obtained the following Equation:

where, node i = j, k, here j and k are the interfacial point between two different media. \(\Delta {u}_{{{\text{N}}i}}^{(p + 1)}\) is the solid phase displacement vector caused by the normal interfacial force \({S}_{{{\text{N}}i}}^{{{\text{s}}p}}\), and \(\Delta {u}_{Ti}^{(p + 1)}\) is the solid phase displacement vector caused by the tangential interfacial force \({S}_{Ti}^{{{\text{s}}p}}\). \(\Delta {U}_{{{\text{N}}i}}^{(p + 1)}\) is the liquid phase displacement vector caused by the normal interfacial force \({S}_{{{\text{N}}i}}^{{{\text{w}}p}}\), and \(\Delta {U}_{{{\text{T}}i}}^{(p + 1)}\) is the liquid phase displacement vector caused by the tangential interfacial force \({S}_{{{\text{T}}i}}^{{{\text{w}}p}}\).

With the interfacial force, the displacement response of the interfacial node can be solved by Eqs. (8) and (9).

Motions of the boundary nodes (artificial boundary conditions)

Assume the soil in the boundary region is linear, with the origin of the x-axis located at the artificial boundary point, and the x-axis perpendicular to the artificial boundary and points to the infinite domain of the external foundation, as shown in Fig. 2. Therefore, the control Equation for the boundary node can be written as Multi-Transmitting Formula (MTF)41,42.

To effectively simulate the motion of the outgoing wave across the artificial boundary, I used the Multi-Transmitting Formula (MTF):

where \({U}_{bs}^{(p + 1)}\) and \({u}_{bs}^{(p + 1)}\) represent the liquid and solid displacement of the scattered wave at the boundary node o at t = (P + 1)Δt respectively, N is the transmitting order, \({C}_{j}^{N}\) here can be expressed as:

Here, \(N\) \((N = 1,2)\) denotes the approximation order of MTF, \(c_{a}\) is artificial speed. The coordinates \(x = - jc_{a} \Delta t\) indicate the sampling points on the x-axis, which is perpendicular to the artificial boundary at a boundary point under consideration. The arguments j and p are integers. Since the point \(x = - jc_{a} \Delta t\) do not generally coincide with the discrete nodes \(x = - n\Delta x\), in order to implement Eq. (10), an interpolation scheme is required to express \(u_{s} (t, - jc_{a} \Delta t)\) in terms of \(u_{s} (t, - n\Delta x)\).

This local artificial boundary condition is universal and has nothing to do with specific wave Equations, which can be directly used for wave problems in saturated porous media. The total displacements UT can be separated as:

In which \({U}_{s}\) represent scattering displacements, and \({U}_{f}\) represent the free field displacements. At first, scattering field at time P is obtained by Eq. (13), where the total displacements at time Pcan be solved by the method mentioned in Discretization and solution of motion Equations, and the free-field displacement can be obtained by the transfer matrix method43 (under seismic wave input). Then, applying Eq. (10) to the solid and liquid phase displacements of a saturated porous medium respectively, the scattered wave field displacement at the boundary point at moment p + 1 can be obtained, and then superimposed on the free field displacement at the boundary point to obtain the total solid and liquid phase displacements at the boundary point.

Nonlinear constitutive model for saturated soil based on a Davidenkov skeleton curve

Under strong ground excitation, the soil near the building foundation (i.e. near-field soil) may behave in an inelastic range. Many nonlinear soil models, from simplified perfect Elastoplastic models to complex models44,45, have been developed to represent near-field soil more accurately. To balance the calculation accuracy and efficiency of large-scale nonlinear seismic site effect analysis, in this paper, the three-dimensional explicit subroutine of Davidenkov model46with simplified loading reloading rules. The Davidenkov model based on three parameters is used because the saturated soil dynamic behavior can be correctly simulated and the parameters can be easily obtained by dynamic triaxial tests47,48.

Martin et al49. first applied Davidenkov’s constitutive model to nonlinear analysis. The Davidenkov model is written as:

where \(\tau (\gamma )\) represents the shear stress, \(\gamma\) is the shear strain and \(G_{\max }\) is the initial shear modulus. A is a curve-fitting parameter called the shape parameter, B is another curve-fitting parameter called the curvature parameter. \(\gamma_{0}\) is the reference shear strain. This reference shear strain is defined as the ratio of the shear strength \(\tau_{f}\) of the soil in the static triaxial tests versus the maximum shear modulus \(G_{\max }\) at a given stress state, i.e. \(\gamma_{0} = {{\tau_{f} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\tau_{f} } {G_{\max } }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {G_{\max } }}\)50. The shear strength \(\tau_{f}\) is defined by the maximum shear stress.

For initial loading, the stress–strain curve follows the skeleton curve, such as the "0 → 1" curve segment in Fig. 3. Equation (26) describes the stress–strain relationship and the hysteretic stress–strain curve is determined by the initial skeleton curve, which is enlarged by \(n\) times. The shear modulus at the turning point is equal to the initial shear modulus.

Taking the derivative of \(\gamma\) in Eq. (15), the time-variant tangential shear modulus of the initial skeleton curve is obtained by:

Taking the derivative of \((\gamma - \gamma_{{\text{c}}} )\) in Eq. (17), the time-variant tangential shear modulus of the hysteresis curves is obtained by:

where the parameter \((2n\gamma_{0} )^{2B}\) is determined based on the current inflection point and the maximum (small) point in history.

The initial tangent slopes were used at time t to approximate the secant modulus at time-steps from t to t + Δt; that is, the stiffness matrix and damping matrix in Eq. (4) can be obtained from the shear modulus \(G_{t}\) and it is calculated by Eq. (18) or (19). The response calculation of the time-steps from t to t + Δt is completed using Eq. (6), and the cycle is repeated step-by-step to obtain the entire time-history response.

Validations of the proposed methodology

Effect of free fields on the non-linear response of a marine site

Model and parameters

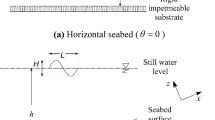

A three-dimensional seawater-saturated soil–bedrock marine site model is considered as shown in Fig. 4. For input seismic waves, the input is a unit pulse is depicted in Fig. 5. The input seismic motion is specified at bedrock and propagated vertically used to calculate the free-field motion. The total duration is 1.6 s with a time step of 0.0002 s and the cut-off frequency is about 25 Hz.

The size of the 3D soil model was set to 60 m × 60 m × 60 m, and the media parameters for each layer are shown in Table 1. The soil is discretized into 1.0 m × 1.0 m × 1.0 m hexahedral solid element in the x-, y- and z-directions51.

The relationship between the dynamic shear modulus ratio G/Gmax-γand the damping ratio λ-γ for the soil were obtained via dynamic triaxial tests. The fitting parameters A = 1.10, B = 0.20 and γ0 = 0.04% were obtained from the fitting method for the saturated soil layer in Nonlinear constitutive model for saturated soil based on a Davidenkov skeleton curve. And the seawater layer and bedrock layer are considered as linear. The calculation is performed on a small workstation, with Intel Core i7 @ 3.40G Hz, the main memory size is 16 G, and the operating system is Ubuntu 16.04 LTS.

Analysis and results

To verify the correctness of the adopted procedure, the following two schemes are available for the calculation of the free field:

(1) The scheme I uses the transfer matrix method to obtain a linear free field;

(2) The scheme II adopts a one-dimensional finite element method with a Davidenkov non-linear intrinsic model for the saturated soil layer with the same parameters as the three-dimensional model and a transmission boundary at the bottom boundary to obtain a non-linear free field. The free field was used as input and the transmissive boundary was applied on the five boundary surfaces (left, back, right, front and bottom) to carry out the 3D non-linear sea area site analysis.

In this paper, it is assumed that the model is a horizontal layered site, the SV wave is incident vertically from the bottom, and the seawater viscosity is neglected, so the SV wave cannot propagate in the seawater layer, and the displacement of the seawater layer should be 0 in the x-direction.

From Fig. 6(a) and (b), we can see that the displacement of point A on the surface of seawater layer in scheme II is 0 in the x-direction. Because, I assumed the model is a horizontal layered site, the SV wave is incident vertically from the bottom, and the seawater viscosity is neglected, therefore, the SV wave cannot propagate in the seawater layer, and the displacement of the seawater layer should be 0 in the x-direction.

Figure 7 shows the response of each monitoring point of the saturated soil and bedrock layers in the 1D and 3D models for scheme II. As can be seen from the figure, the responses of the 1D and 3D models are in good agreement with each other, verifying the reliability of the non-linear free-field inputs.

Characterization of the non-linear response of the marine site

From Effect of free fields on the non-linear response of a marine site, we know that by considering the linear and nonlinear cases of saturated soil separately, the same model and pulse input were used to analyse the impact of saturated soil nonlinearity on the response of marine sites.

For the linear case, the propagation process of SV waves in the site is plotted in Fig. 8, and each wave peak is estimated based on the bedrock layer shear wave velocity c3 and soil layer shear wave velocity c2, \(\Delta t_{3} = H_{3}^{{}} /c_{3} = 0.0750s\), \(\Delta t_{2} = H_{2}^{{}} /c_{2} = 0.0844s\)。

According to the literature52, it is known that when the SV wave is incident vertically, after omitting the higher order term, the reflection coefficient of the traveling wave at the bedrock layer-saturated soil layer partition interface:

where the wave impedance ratio \(\psi = {{\rho_{2} c_{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\rho_{2} c_{2} } {\rho_{3} c_{3} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\rho_{3} c_{3} }}\), \(\rho_{2}\) and \(\rho_{3}\) are the densities of the bedrock and saturated soil layers, respectively. The reflection coefficient at the bedrock-saturated soil layer interface is R1 = 0.547. The upward wave transmission coefficient can be written as:

The transmittance coefficient at the bedrock interface is T1 = 1.547. Similarly, the upward wave reflection coefficient at the saturated soil-seawater layer interface is 1, and the downward wave reflection coefficient at the bedrock-saturated soil layer interface is −0.547, with a transmission coefficient of 0.453. Tables 2 and 3 compare the actual values of wave arrival time and amplitude with the theoretical values, and the errors are small, proving that the linear case simulation is accurate.

Comparing the linear and non-linear results we can find that when the SV wave incidence is transmitted to the saturated soil layer, the soil skeleton enters a nonlinear state, and the shear modulus G2 decreases, then the shear wave velocity c2 decreases, so the wave impedance ratio \(\psi\) decreases, and 0 < \(\psi\) < 1. According to Eqs. (20) and (21), the reflection coefficient R1 increases, and the transmission coefficient T1 also increases, so the peak of wave peaks 2’, 3‘and 4’is larger than that of the linear case, as shown in Fig. 9. In Fig. 9(a), the peak of wave 5’should have increased, but due to the non-linear damping effect of the saturated soil layer, the peak decreases instead. At the same time, in Fig. 9, the arrival times of wave peaks 5’, 6', 7' and 8’ are delayed compared to the linear case because the shear wave speed c2 decreases. On the other hand, according to Eq. (21), when the shear wave speed c2 decreases, \(\psi\) increases and \(\psi\) > 1, the transmission coefficient T1 at the bedrock-saturated soil intersection decreases, and together with the damping effect of the non-linearity of the saturated soil layer, the peaks of wave peaks 6’, 7' and 8’ decrease significantly.

In addition, for the liquid phase of the saturated soil layer, viscous forces dominate compared to inertial forces. Therefore, the liquid phase displacement time history in Fig. 9(b) and 9(d) shows a clear diffusion process.

Results analysis

Water-site-structure interaction

In this paper, the interaction between the wind turbine structure pile body and the site (seawater, saturated soil layer, and bedrock layer) is mainly considered. A three-dimensional finite element model of a wind turbine with a soil-structure interaction system is depicted in Fig. 10. The numerical model includes four components, viz. wind turbine structure, foundation, layered soil site, and sea water. The total length of the circular pile is 60 m, the section above sea water is 10 m long, the pile section diameter is 4 m and the section below water is 44 m. The additional counterweight section above is 6 m in diameter and 6 m high. The saturated soil layers are calculated for both linear and non-linear scenarios respectively, and the site, pile and bearing parameters are shown in Table 1 and Table 4. For input seismic waves as shown in Fig. 5. In the numerical simulations, the coupling between the wind turbine blades and the atmospheric fluid is not considered, so the mass of the turbine is converted into an additional mass at the pile end to consider the static load on the head of the turbine.

Due to the presence of the pile and the structure, the movement of the pile will cause the movement of the seawater, as can be seen in Fig. 11(a) and (b), there is a certain displacement of the seawater layer. As can be seen from Figs. 11(c)–(k), the top of the bearing and upper part of the pile displacement amplitudes are smaller for the non-linear case than for the linear case, due to the non-linearity of the saturated soil layer considered. The displacement of the bedrock layer in the non-linear case is mainly the initial incident wave and its reflection at the bedrock layer-saturated soil layer interface, the amplitude of the transmitted wave from the saturated soil layer is small for the same reasons as analysed in Characterization of the non-linear response of the marine site. From Fig. 11(l), we can find that the displacement at the bottom of the pile will decrease after 0.25 s for the non-linear case because of bedrock layer.

Based on the displacement of the pile nodes, the shear force and bending moment on the horizontal section of the pile at different heights can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 12. We can find that the maximum shear force and maximum bending moment along the pile body is overall smaller for the non-linear saturated seabed compared to the linear saturated seabed case. The bending moment at the pile head (depth = −10 m) is larger in both the linear and non-linear cases and is extremely large near the soil interface (at 10 m and 30 m) and near the pile end.

Seismic response analysis of bridge in consideration of water-site-structure interaction

In this section, the effect of water-site-structure coupling, non-uniform excitation, and soil-structure interaction on the seismic response of a bridge at a site is investigated by varying the water depth and the seismic wave incidence angle. Since it is in an earthquake-prone area, it is necessary to study its seismic response of the structure in water under seismic action and the degree of influence of the water body on the seismic response of the structure.

Model and parameters

A multi-span continuous girder bridge at a certain place is adopted as the example in this study. The site conditions, heights of pile foundation, and bridge piers have some differences along the longitudinal direction of the bridge. Here the differences are ignored, and the soil is simplified as layered soil. For the influence of adjacent bridge spans, only the weight of girder is considered. The dimensions of the bridge and its main sections are shown in Fig. 13. The bridge has ten spans of 50 m, 50 m, 122 m, 124 m, and 220 m, respectively, so the total length is 816 m. The main bridge is a continuous rigid structure with a maximum span of 220 m. The approach bridge is a simply supported girder with a span of 50 m. The main bridge is a variable section continuous rigid structure with a single box and single chamber main girder section, and the concrete specification used is C60.

In Fig. 13, the pier height of the main bridge abutment is 154 m for Pier No. 5 and 162 m for Pier No. 6, respectively, which are reinforced concrete rectangular hollow piers, and the concrete specification used is C50, and the bearing platform under the main bridge abutment has a height of 6 m, with a plan dimension of 18.0 m × 14.0 m, and the foundation is a 4 × 3 arrangement of square piles of 2.0 m × 2.0 m, and the concrete specification used for the bearing platform and the pile foundation are both C30. Junction pier using reinforced concrete rectangular hollow pier, the concrete specifications used for the C50, which is Fig. 13, Pier 4, height of 106 m, and Pier 7, height of 104 m, the height of the bridge pier is 4.0 m, the plane size of 10.0 m × 14.0 m, the foundation for the 2 × 3 arrangement of 2.0 m × 2.0 m square piles, the bearing and pile foundation concrete specifications are used for the C30.The approach piers are reinforced concrete rectangular solid piers, the concrete specification used is C50, the height of the bridge pier is 2 m, the plan dimension is 10.0 m × 10.0 m, the foundation is 2 × 2 arrangement of 2.0 m × 2.0 m square piles, and the concrete specification used for the abutment and the pile foundation is C30. Table 5 shows the material parameters of the bridge.

The three-dimensional finite element model of the bridge is implemented in the commercial finite element software ANSYS, as shown in Fig. 14(a). The main girders of the main bridge and approach bridge are simulated with BEAM188 girder elements and the piers, cover girders and abutments are simulated with hexahedron eight node solid elements (SOLID185).

The BEAM188 element is based on the Timoshenko beam structure theory, which considers the effect of shear deformation and is suitable for analysing the main girders of the bridge with variable section and T-section girders. The variable section segments are modelled using the SECTYPE command in APDL language. And the coupling constraints between piers and girders are applied at the supports of the bridge through CE and CERIG commands in ANSYS APDL language. As shown in Fig. 14(b) and (c), the simply supported girders are coupled in the corresponding directions through CE commands, and at the continuous stiffeners the rigid regions are generated through CERIG command.

Modal analysis of the finite element model of the bridge was carried out, firstly to verify the correctness of the model and secondly to obtain the correlation coefficients of Rayleigh damping for the subsequent selection of the corresponding frequencies. The results of the modal analysis of the bridge structure used in this paper as shown in Fig. 15. From Table 6, we can find that the first, second and fourth order vibration modes are the local vibration modes of the longitudinal bridge wise bending of the side piers on both sides, which is due to the weak constraints on the top of the side piers by the main beams. The third-order mode is the longitudinal bending mode of the center pier, the fifth and sixth-order modes are the symmetric and anti-symmetric transverse bending modes of the main girder, and the seventh, eighth and ninth-order modes are the longitudinal bending modes of the secondary main girder.

Input seismic wave

This paper mainly studies the effect of site-reservoir-bridge interaction on the seismic response of the structure, while the effect of moving water on the structure under vertical excitation is limited, so I choose to design the acceleration response spectrum in the horizontal direction. As the effect of the hydrodynamic force on the seismic response of the bridge under vertical earthquake could be ignored, only the horizontal waves were put in the model.

According to the " Specifications for Seismic Design of Highway Bridges" (JTG/T 2231–01-2020) and "Seismic ground motion parameters zonation map of China" (GB 18,306–2015), it is known that the characteristic period of its class II site Tg = 0.45 s, and the horizontal peak basic ground vibration acceleration A = 0.15 g. Also, according to the geology of the site, it is known that the site is classified as I0, and according to the Code, the characteristic period Tg is adjusted. In this paper, I carry out the first stage of seismic analysis of the bridge, i.e. E1 seismic action, the seismic response of the bridge. In summary, the design acceleration response spectrum correlation coefficients are shown in Table 7. After screening, the seismic waves were amplitude-modulated and selected to satisfy the conditions, and their response spectra and design acceleration response spectra are shown in Fig. 16.

According to the modal analysis of the bridge, the cycles of the first few modes of the structure are mainly in the descending section of the response spectrum, and the specification requires that the seismic wave acceleration response spectra in the structural cycle values corresponding to the response spectrum amplitude relative to the design of the acceleration response spectra amplitude should have an absolute error of less than 0.01 g. The three seismic wave acceleration response spectra in the corresponding cycle errors are shown in Table 8.

The seismic wave used in this example is from the San Onofre Nuclear Power Station in Southern California, USA, which recorded the earthquake that occurred on 9 April 1968 at Borrego Mountain, and is hereafter referred to as Borrego-San Onofre-19680409, with the nomenclature of place of seismic, station of record, and date of seismic. To make the seismic wave conform to the specification design acceleration response spectrum, the acceleration amplitude of the seismic wave was processed, and its peak acceleration was adjusted to 0.09 g. The duration of the Borrego-San Onofre-19680409 seismic wave was 45.2 s. Its acceleration time-range spectrum and displacement time-range spectrum are shown in Fig. 17.

Analysis of calculation results

In this paper, to study the influence of related factors on the seismic response of large-span deep-water bridges, the site area is selected to be 1000 m × 50 m × 400 m (as shown in Fig. 18), the terrain is a V-shaped canyon. The effect of infinite soil domain is considered by the Multi-transmitting boundary. The site-related parameters are shown in Table 9.

(1) Effects of reservoir depth.

To investigate the effect of water depth variation on the seismic response of a large span deep-water bridge, three working conditions are designed, see Fig. 19. Where the site material is bedrock (Site 2), the seismic wave is incident vertically from the bedrock surface, and the water depths are 0 m (no water), 100 m (semi-full reservoir), and 200 m (full reservoir), respectively.

Under the action of seismic waves, the highest pier of the bridge, pier 6, is selected, and the time history and spectrum of the displacement along the x-direction at the reference point at the bottom of the pier are shown in Fig. 20.

From Table 10, by comparing the responses of CASE1, CASE2, and CASE3, the influence of water-structure interaction which neglects pile-soil interaction is obtained. It can be found that the hydrodynamic force slightly changes the dynamic response of the structure. Table 10 describes the peak displacement response and peak arrival time of the reference point at the bottom of each bridge pier along the x-direction under the seismic wave. The data presented in the table indicate that the Pier 6 (depth = 162 m), being the highest, reaches its peak displacement first. In contrast, piers 1(depth = 36 m) and 9(depth = 36 m), which are shorter, experience peak displacement later. Notably, pier 9 reaches its peak after pier 1, which aligns with the expected effects of seismic waves, confirming that the simulation results are consistent with the actual situation.

Compared CASE1, CASE2, and CASE3, it can be found that with the increase of water depth, the peak displacement of the reference point at the bottom of each pier does not change much, and the main trend is to decrease. When the reservoir is full of water, the peak displacement of the reference point at the bottom of Pier 6 along the x-direction is greatly reduced compared with the no-water condition, reaching 1.08%, which shows that the response at the bottom of the pier is not much affected by the water depth.

To describe the peak displacement of the x-direction more intuitively at the bottom of the bridge abutment under the action of seismic waves. From the Fig. 21, the peak displacement of the reference point at the bottom of the bridge abutment decreases with the increase of water depth. The reason for this may be related to the spectral characteristics of seismic waves, seismic wave main frequency is less than 0.2 Hz. The site’s irregular topography affects peak displacement at the base of the abutments, which varies with elevation. Notably, the lower elevations of abutments No. 5 (depth = 154 m) and No. 6 (depth = 162 m) exhibit smaller peak displacements compared to the other abutments. This observation supports the conclusion that excitation at the bottom of the canyon is less than that on the slope surfaces.

Figure 22 shows the time history of the displacement of the main girder of the bridge approach at the support (x-direction). From the figure, the displacement response at the support tends to increase as the water depth increases. However, it can be seen from Fig. 22(d) that the displacement response of the approach bridge at the most side span is basically unaffected by the change of water depth.

The time history of shear force at the reference point at the bottom of some of the piers of the bridge is shown in Fig. 23. From the figure the pier bottom shear of the approach bridge abutments increases with increasing water depth. The pier bottom shear of the junction abutment and the main bridge abutment piers decreases with the increase of water depth, while the pier bottom shear of Abutment 5 exhibits a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase of water depth. When the water depth of CASE2 is 100 m, the water surface only covers Piers 5 and 6, so its effect on the bottom shear force is greater compared to other piers. When the water depth of CASE3 is 200 m, the water surface covers the bottom of all piers, which has different effects due to the different forms of connection between the top of piers and the main girder.

The variation of peak shear force at the reference point at the bottom of each abutment under seismic wave is shown in Fig. 24. As can be seen from the figure, the peak shear force at the bottom reference point of the abutment generally decreases with the increase of the water depth, but the trend of the change of Abutment 5 shows an increase and then a decrease. At full reservoir (CASE3), the peak shear force at the bottom of Abutment 6 decreased by 60.6% compared to the no-water condition (CASE1), while the peak shear force at the bottom of Abutment 5 increased by 67.0% in CASE2. The reason is mainly because the pier heights are different, the dynamic characteristics of each pier are also different, and the change of water depth causes the dynamic characteristics of the piers to change, so they show different changes under the same seismic wave. When the water depth covers all the piers, the peak shear force difference at the bottom of each pier decreases.

(2) Impact of site conditions.

To investigate the effect of changing site conditions on the seismic response of large-span deepwater bridges, the site is divided into three working conditions, Site 1 (saturated soil, CASE 4), Site 2 (bedrock, CASE 5), and two types of site layering (CASE 6), as shown in Fig. 25. Site related parameters are shown in Table 9.

The displacement time history and spectrum (x-direction) at the bottom of bridge Abutment 6 are shown in Fig. 26. And the peak displacement at the bottom of each abutment under seismic wave is shown in Table 11. We found that the effect of site change on the excitation of the bottom of the abutment is small. The impact of site changes on the excitation at the bottom of the abutment is minimal. As shown in Table 11, different geological models (CASE4, CASE5, and CASE6) yield a maximum peak displacement of 0.0645 m (Abutment No. 9) and a minimum of 0.0612 m (Abutment Nos. 5 and 6), resulting in a maximum variation of 5.4%. Therefore, the peak displacement response across various abutments remains relatively consistent. From the Table 11, due to the softening of the site, the modulus of elasticity of the site becomes smaller, and the shear wave velocity in the site decreases, so the peak displacement in the main direction arrives after a time delay, in line with the regular change. Secondly, the displacement of Pier 3 in CASE5 increased by 1.7%, and the displacement of Pier 6 in CASE6 decreased by 3.6%.

Figure 27 depicts the peak displacement response at the base of each abutment under seismic wave action. From the figure, with the change of the site material, the intrinsic frequency of the site changes, resulting in the displacement response at the bottom of the piers under the same seismic wave excitation. The overall trend is to increase and then decrease, which may be since CASE6 is an inhomogeneous geology, and its scattering will be more intense, causing the ground motion to be more obvious.

Figure 28 shows the peak displacements at the main girder supports of the approach bridge under seismic waves. Comparing CASE 4, CASE 5, and CASE 6, the locations of the peak displacements change significantly, which may be due to the change of seismic wave excitation transmitted to the bridge with the change of the site. In addition, the change in the site leads to a change in the interaction between the site and the reservoir water, thus causing a change in the location of the peak displacement at the main girder support of the approach bridge along with the dynamic characteristics of the abutment.

Figure 29 illustrates the shear force time history curves (x-direction) at the bottom reference point of Abutment 5 and Abutment 9. It can be found that the peak shear force at the bottom reference point of the abutment becomes larger as the site becomes softer. The variation curves of the peak shear force at the bottom reference point of each abutment under the action of seismic wave are shown in Fig. 30. From the figure, it can be seen that overall the peak shear at the bottom of the abutment increases with the decrease of the average shear wave velocity of the site. The peak shear in CASE 6 between Abutment 5 and Abutment 6 increases significantly, and the peak shear at Abutment 6 increases by 69.2% compared to CASE 4.

In summary, we can find that under the harder site conditions (Site 2), the bottom response of the piers is unaffected as the water depth increases, while the shear force at the bottom of the piers decreases with the increase of water depth. Among them, the bottom shear force of Pier 5 shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing, which is related to the dynamic characteristics of the pier. The main girder due to the different connection with the abutment, with the increase of water depth shows different trends, the main girder displacement of the simply supported approach bridge generally increases with the increase of water depth, while the displacement of the rigid main bridge decreases with the increase of water depth. As the site becomes softer, the intrinsic frequency of the site decreases, making the response of the abutment section change, while the shear force at the bottom of the abutment increases with the increase of the ratio of site modulus to structural modulus. The results associated with the algorithms are consistent with the basic laws of seismic response of deepwater bridges. This also verifies the correctness of the proposed method from the side.

Conclusions

This paper develops a method for analysing the seismic response of a marine site and a seawater-seabed-structure system. A unified computational framework for coupled seawater, saturated seabed, and bedrock fluid–solid analysis is used for the inner domain nodes, and the effect of the infinite domain is modeled using a transmission boundary. The effect of the free field on the results of the non-linear response analysis of the sea site is discussed, and the difference in response between the linear and non-linear saturated sea bed cases is analysed. The effect of water-site-structure coupling and soil condition on the seismic response of the bridge is investigated by varying the water depth. The following conclusions are obtained:

-

(1)

For the example in this paper, the linear free field will cause a large error when calculating the nonlinear seismic response of the marine site, and the nonlinear free field should be used, and the principal structure of the free field analysis should be consistent with that of the marine site analysis;

-

(2)

As the saturated soil layer enters non-linearity, compared with the linear case, the nonlinearity will decrease the site modules and increase the damping. The reflection and transmission coefficients incident from the bedrock to the saturated soil layer both increase and the response of the bedrock is larger than in the linear case. As the transmission coefficient increases, the response of the saturated soil layer should increase, but due to the increased damping in the non-linear case, the response of the saturated soil layer is smaller than that in the linear case (the peak displacement decreased by about 58.6%, as illustrated by wave peaks 5 and 5'in Fig. 9(a)), and then during time is shorter;

-

(3)

For the example in this paper, the maximum bending moment and shear force along the pile body in the non-linear saturated seabed case are smaller than those in the linear saturated seabed case (as shown in Fig.12, the maximum shear force differs by approximately 57.4% at depth =50 m, while the maximum bending moment varies by about 73.3% at depth=0 m.), and the structural damage caused by the non-linear saturated seabed may mainly be reflected in the foundation failure caused by the liquefaction of the seabed;

-

(4)

From the example, I found that under the harder site conditions, the bottom response of the piers is unaffected as the water depth increases, while the shear force at the bottom of the piers decreases with the increase of water depth (the peak shear at Abutment 6 increases by 69.2% compared to CASE1 (saturated soil, Site 1)). As the site becomes softer, the intrinsic frequency of the site decreases, making the response of the abutment section change, while the shear force at the bottom of the abutment increases with the increase of the ratio of site modulus to structural modulus.

In this paper, the model is discretized into cubit elements with a unified size. However, when the medium wave velocity in the model varies greatly, or the surface terrain of the model changes drastically, the element size needs to be reduced to meet the numerical stability requirements, which increases the computational load. In the subsequent study, the hybrid grid would be used to discretize the model in my code, which can ensure computational accuracy and radically reduce the computational load53.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Nakamura, T., Nakano, M., Hayashimoto, N., Takahashi, N., Takenaka, H., Okamoto,T., et al. 2014. “Anomalously large seismic amplifications in the seafloor area off the Kii peninsula.” Mar. Geophys. Res. 35 (3): 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-014-9211-2.

Hu, J. J., Tan, J. Y., and Zhao, J. X. 2020. “New GMPEs for the Sagami bay region in Japan for moderate magnitude events with emphasis on differences on site amplifications at the seafloor and land seismic stations of K-NET.” Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 110 (5):2577–2597. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120190305

Brekhovskikh, L. M. 1980. “Waves in layered media. 2nd edtion.” NY, USA: Academic Press.

Thakoor, K., Andrews, J., Hauksson, E. & Heaton, T. From Earthquake Source Parameters to Ground Motion Warnings near You: The Shake Alert Earthquake Information to Ground Motion (eqlnfo2Gm). Method Seismological Research Letters. 90(3), 1243–1257 (2019).

Qian, Zhenghua., Hiroaki Yamanaka.2012. “An efficient approach for simulating seismoacoustic scattering due to an irregular fluid–solid interface in multilayered media.” Geophysical Journal International. 189:524–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-246X.2011.05352.X

Li, C., Hao, H., Li, H. N., Bi, K. M., and Chen, B. K. 2017. “Modeling and simulation of spatially correlated ground motions at multiple onshore and offshore sites.” J. Earthq. Eng. 21 (3):359–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2016.1172375.

Ke, X. F., Chen, S. L. & Zhang, H. X. Free-field analysis of seawater-seabed system for incident plane P-SV waves. J. Vib. Eng. 32(6), 966–976 (2019) ((in Chinese)).

Zhao, K., Zhu, S., Bai, X.F., Wang, Q., Chen, S., Zhuang, H., & Chen, G. 2021. “Seismic response of immersed tunnel in liquefiable seabed considering ocean environmental loads.” Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology. 115, 104066. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TUST.2021.104066

Tang, Xinhu., Chen, Peng. 2024.“Combined Earthquake-Wave Effects on the Dynamic Response of Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridges.” Advances in Civil Engineering. 6109335,17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6109335

Arablouei, A. et al. Effects of seawater-structure-soil interaction on seismic performance of caisson-type quay wall. Comput. Struct. 89(23), 2439–2459 (2011).

Ye, J. H. & Wang, G. Seismic dynamics of offshore breakwater on liquefiable seabed foundation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 76, 86–93 (2015).

Weiyun, C. et al. Seismic response and damage analysis of immersed tunnel considering the seabed-seawater coupling effect. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2024.108853 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Wind, wave and earthquake responses of offshore wind turbine on monopile foundation in clay. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 113, 47–57 (2018).

Morency, C., and Tromp, J. 2008. “Spectral-element simulations of wave propagation in porous media.” Geophys. J. Int. 175 (1): 301–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246x.2008.03907.x

Link, G., Kaltenbacher, M., Breuer,M., and Döllinger, M. 2009. “A 2D finite-element scheme for fluid-solid-acoustic interactions and its application to human phonation.” Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 198 (41–44):3321–3334. 1016/j.cma.2009.06.009.

Liu, J. B., Bao, X., Wang, D. Y., and Wang, P. G. 2019. “Seismic response analysis of the reef-seawater system under incident SV wave.” Ocean. Eng. 180:199–210. 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.03.068.

Chen, S. L., Ke, X. F. & Zhang, H. X. A unified computational framework for fluid-solid coupling in marine earthquake engineering. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 51(2), 594–606 (2019) ((in Chinese)).

Chen, S. L., Cheng, S. L. & Ke, X. F. A unified computational framework for fluid-solid coupling in marine earthquake engineering: Irregular interface case. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 51(5), 1517–1529 (2019) ((in Chinese)).

Takemura, S. et al. Centroid moment tensor inversions of offshore earthquakes using a three-dimensional velocity structure model: Slip distributions on the plate boundary along the nankai trough. Geophys. J. Int. 222(2), 1109–1125 (2020).

Wang X, Zhan ZW. 2020. “Moving from 1-D to 3-D velocity model: Automated waveform-based earthquake moment tensor inversion in the losangeles region.” Geophys. J. Int. 220(1):218–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggz435

Bao X, Liu J, Chen S, Wang P. 2022. “Seismic analysis of the reef-seawater system: Comparison between 3D and 2D models.” J. Earthq. Eng. 26(6):3109–3122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632469.2020.1785976

Okamoto T, Takenaka H, Nakamura T, Aoki T. 2010. “Accelerating large-scale simulation of seismic wave propagation by multi-GPUs and three-dimensional domain decomposition.” Earth, Planets Space. 62 (12):939–942. https://doi.org/10.5047/eps.2010.11.009

Liu SL, Yang DH, Dong XP, et al. 2017. “Element-byelement parallel spectral-element methods for 3-D teleseismic wave modeling.” Solid earth. 8(5):969–986.

Maeda T, Takemura S, Furumura T. 2017. “Open SWPC: An open-source integrated parallel simulation code for modeling seismic wave propagation in 3D heterogeneous viscoelastic media.” Earth, Planets Space. 69(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0687-2

Idriss, I. M. & Seed, H. B. Seismic response of horizontal soil layers. Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundation Division. ASCE 94(SM4), 1003–1031 (1968).

Johari, A., Vali, B. & Golkarfard, H. System reliability analysis of ground response based on peak ground acceleration considering soil layers cross-correlation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 141, 106475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106475 (2021).

Li, J., Yin, Z.-Y., Cui, Y.-J., Liu, K. & Yin, J.-H. An elasto-plastic model of unsaturated soil with an explicit degree of saturation-dependent CSL. Engineering Geology. 260, 105240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105240 (2019).

Dingfeng Zhao, Bin Ruan, Guoxing Chen. 2016. “Validation of the Modified Irregular Unloading-Reloading Rules Based on Davidenkov Skeleton Curve and the Implementation in ABAQUS Software.” International Collaboration in Lifeline Earthquake Engineering 2016 (IRP1). https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784480342.061

Hashash YMA, Groholski DR, Phillips CA, et al. 2011. DEEPSOIL 5.0 user manual and tutorial.

Győri, E., Tóth, L., Gráczer, Z. et al.2011. “Liquefaction and post-liquefaction settlement assessment — A probabilistic approach.” Acta Geod. Geoph. Hung. 46:347–369. https://doi.org/10.1556/AGeod.46.2011.3.6

Zhao, Y. X. & Chen, S. L. Discussion on the matrix propagator method to analyse the response of saturated layered media. Chinese Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. 48(5), 1145–1158 (2016) ((in Chinese)).

Chen, S. L. & Zong, J. Wave Input Method for Three-dimensional Wave Scattering Simulation of an Incident Wave in an Arbitrary Direction. Chinese Journal of Solid Mechanics. 39(1), 80–89 (2018) ((in Chinese)).

Li, S. Y. & Liao, Z. P. Wave-type conversion caused by a step topography subjected to inclined seismic body wave. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 22(4), 9–15 (2002) ((in Chinese)).

Liu, J. B. & Wang, Y. A 1-D time-domain methed for 2-D wave motion in elastic layers half-space by antiplane wave oblique incidence. Chinese Journal of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. 38(2), 219–225 (2006) ((in Chinese)).

Lou, J., Fang, X., Fan, H. & Du, J. K. A nonlinear seismic metamaterial lying on layered soils. Engineering Structures. 272, 115032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.1150 (2022).

Chen SL, Lv H, Zhou GL. 2022. “Partitioned analysis of soil structure interaction for nuclear island building.” Earthq. Eng. Struct. D. 51:2220–2247. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3661.

Lv, H. & Chen, S. L. Analysis of nonlinear soil structure interaction using Partitioned method. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 162, 107470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn2022.107470 (2022).

Lv, H. & Chen, S. L. Seismic response characteristics of nuclear island structure at generic soil and rock sites. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 22, 667–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-023-2186-8 (2023).

Biot, M. A. Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid-saturated porous solid. Acoust Soc Am. 28, 168–191 (1956).

Biot, M. A. Mechanics of deformation and acoustic propagation in porous media. Journal of Applied Physics. 33(4), 1482–1498 (1962).

Liao, Z. P. & Wong, H. L. A transmitting boundary for the numerical simulation of elastic wave propagation. International Journal of Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 3, 174–183 (1984).

Chen, S. L. & Liao, Z. P. Multi-transmitting formula for attenuating waves. Acta Seismologica Sinica. 16(3), 283–291 (2003).

Thomson, W. T. Transmission of Elastic Waves through a Stratified Solid Medium. Journal of Applied Physics. 21(2), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1699629 (1950).

Anastasopoulos, I. et al. Simplified constitutive model for simulation of cyclic response of shallow foundations: validation against laboratory tests. J Geotech Geoenv- ironmental Eng. 137(12), 1154–1168. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000534 (2011).

Karatzetzou A, Fotopoulou S, Riga E, et al. 2014. “A Comparative Study on Nonlinear Soil Response Analysis.” Second European Conference on Earthquake Engineering and Seismology.25–29 August 2014, Istanbul, Turkey.

Zhao DF, Ruan B, Chen GX. 2016. “Validation of the modified irregular unloading-reloading rules based on Davidenkov skeleton curve and the implementation in ABAQUS software.” International Collaboration in Lifeline Earthquake Engineering, ASCE. Shanghai.

Chen, G. X. et al. “Nonlinear analysis on seismic site response of Fuzhou Basin, China. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 105(2A), 928–949 (2015).

Hassan L, Robert A, Arnau C, et al. 2022. “A 2.5D coupled FEM–SBM methodology for soil-structure dynamic interaction problems.” Eng. Struct. (250),113371. 10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113371271–278.

Martin, P. P. & Seed, H. B. One-dimensional dynamic ground response analyses. Journal of Geotechnical Engineering. ASCE 108(7), 935–952 (1982).

Hardin, B. O. & Drnevich, V. P. Shear Modulus and Damping in Soils: Design Equations and Curves. Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division. 98(7), 667–692 (1972).

Roger LK, John L. 1973. “Finite element method accuracy for wave propagation problems. Journal of Soil Mechanics & Foundations Division. ASCE. 99(5):421–427. https://doi.org/10.1061/JSFEAQ.0001885.

Nirakara Pradhan, Sapan Kumar Samal。2022. “Surface waves propagation in a homogeneous liquid layer overlying a monoclinic half-space.” Applied Mathematics and Computation. 414, 126655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2021.126655.

Ichimura T, Hori M, Kuwamoto H. 2007. “Earthquake motion simulation with multiscale finite-element analysis on hybrid grid. Bull.” Seismol. Soc. Am. 97(4):1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120060175

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my PhD supervisor, Prof. Shaolin Chen, for sharing their methodology and experience with me and making this work possible. I sincerely thank my postdoctoral co-supervisor, Prof. Qingbiao Wang, for providing all support. The authors acknowledge and appreciate the support provided by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant Number: GZC20231496, and the Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. SDCX-ZG-202400217).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hao Lv: Data curation, Methodology, Writing original draft, and review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, H. Application research on nonlinear partitioned analysis of soil-structure interaction method of seismic response for seawater-seabed-structure. Sci Rep 14, 27817 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79056-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79056-0