Abstract

In 2022, the MS 6.9 Menyuan (Qinghai Province) and MS 6.8 Luding (Sichuan Province) earthquakes occurred successively on China’s North–South seismic belt. Both earthquakes caused serious property losses, and the Luding earthquake caused 100 + casualties. Gravity observations performed in the North–South Seismic Belt before the two earthquakes indicate that gravity changes occurred near the epicentres and exhibited four-quadrant distributions. In this study, We reviewed the successful prediction of these two earthquakes by using gravity data. The distances between the actual and predicted epicenters of the two earthquakes were < 56 km in 2022 and < 10 km in 2021. Before both earthquakes, gravity changes first showed as a gradient zone consistent with the strike of seismogenic fault, and then subsequently exhibited a four-quadrant distribution around the epicentral regions. The earthquakes occurred near the centres of the four-quadrant change and the zero isoline of gravity change. In summary, the gravity data reflected both earthquakes well. The findings indicate that such four-quadrant distributions and gravity change high-gradient zone may be precursor information of earthquake preparation. The results of this study provide a reference for future earthquake monitoring and prediction, with implications for earthquake hazard assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earthquakes can have substantial impacts on human survival and socioeconomic development owing to their unexpected and destructive nature. In 2022, the MS 6.9 Menyuan and MS 6.8 Luding earthquakes occurred successively in China’s North–South Seismic Belt. Before the earthquakes occurred, gravity anomalies were observed near the epicentres, and successful mid-term predictions (Medium-term prediction refers to the prediction of the region and intensity where destructive earthquakes may occur in the next one or two years) were conducted. Table 1 summarises the predicted locations and magnitudes of the two earthquakes, which were obtained from the “Comprehensive Analysis of Dynamic Changes of Gravity Field in Central and Western Chinese mainland” sections of the 2021 and 2022 earthquake trend research reports produced by the Second Monitoring Centre of the China Earthquake Administration (hereafter the Second Measurement Centre).

Table 1 indicates that the Menyuan and Luding earthquake epicentres predicted in 2021 and 2022 were very accurate, with distances from the actual epicentres of less than 56 km. In particular, the epicentres predicted in the 2021 report were less than 10 km from the actual epicentres, which is the most accurate prediction of the potential location for strong earthquake (magnitude 6 or above) at home and abroad. In recent years, significant gravity anomaly changes have been observed in the mobile gravity data before several strong earthquakes in the North–South Seismic Belt. Although the manifestations of the anomalies have not been consistent, some earthquakes occurred in the high-gradient zone and zero-value isoline area where the positive and negative gravity anomalies transitioned, and some earthquakes occurred at the centres of the four-quadrant distributions of the gravity anomalies. However, the potential locations and magnitudes of strong earthquakes can be investigated using the ranges and amplitudes of the gravity anomalies, as well as the gravity anomaly gradient sizes and characteristics1,2. Based on the anomaly changes in the regional gravity field, we have previously made mid-term predictions for the 2008 MS 8.0 Wenchuan, 2013 MS 7.0 Lushan, and 2017 MS 7.0 Jiuzhaigou earthquakes, which were consistent with the actual earthquake locations3,4,5,6 (72 km4,7, 77 km5, and 220 km6 from the epicentres, respectively). Although few gravity measurement sites were located near the Jiuzhaigou earthquake epicentre (distance between sites > 100 km), and the predicted epicentre was more than 200 km from the actual epicentre, it is explicitly mentioned in the location determination to pay attention to the possibility of earthquakes occurring in the area of Jiuzhaigou and Zoige in Sichuan6,8,9. After the 2017 Jiuzhaigou earthquake, the China Earthquake Administration strengthened mobile gravity monitoring on the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, particularly the observational density in key risk areas (two observations per year, 30–60 km between sites), which provided reliable data for the Menyuan and Luding earthquake predictions performed in 2022. In the past, the predicted epicentre of the earthquake was basically more than 70 km away from the actual epicentre of the earthquake. The epicentre of the MS 6.9 earthquake in Menyuan and MS 6.8 earthquake in Luding in 2022 was determined to be within 50 km, which is two accurate predictions. These predictions confirm that high-density gravity data have unique advantages for determining the locations of future earthquakes2,9,10.

In this study, we analysed the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and laws of the regional gravity field before the Menyuan MS 6.9 and Luding MS 6.8 earthquakes in 2022, summarized the process of earthquake prediction and the basis of prediction, and proposed a new seismic monitoring model based on gravity observations, which will point out the direction of the innovation of future seismic monitoring methods and prediction practice11,12.

Data and methods

The mobile gravity seismic monitoring network in mainland China comprises relative gravity survey and absolute gravity control networks9,13, and regularly repeated seismic gravity surveys are performed annually. The North–South Seismic Belt is a key earthquake monitoring area in mainland China, and hosts many absolute and relative gravity measuring sites. The absolute gravity was measured using FG-5 absolute gravimeters, which have an accuracy better than 5 × 10− 8 ms− 2 14,15. Burris, LCR-G, CG5, and CG6 gravimeters were used to measure relative gravity, with measurement accuracies better than 10 × 10− 8 ms− 2 for gravity segment differences12,16. We use the classical adjustment method to adjust the observed data of absolute gravity and relative gravity in the north-south seismic belt as a whole2,16, and use the absolute gravity values as the starting basis to obtain the gravity values at each measurement point. We used these data to determine the dynamic change characteristics of regional gravity field at different time and space scales before the 2022 Menyuan and Luding earthquakes.

Results

Dynamic gravity field changes before the Menyuan earthquake

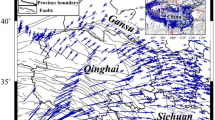

From October 2018 to October 2020 (Fig. 1a), a negative gravity change occurred on the northern side of the Tuolaishan Fault, with a corresponding positive gravity change on the southern side of the fault. A WNW-trending gradient zone between the gravity changes was located near the Tuolaishan Fault, and turned around near the 2022 Menyuan earthquake epicentre. The differential gravity changes on both sides of the Tuolaishan and Lenglongling faults near the epicentre were greater than 60 × 10− 8 ms− 2.

From October 2020 to July 2021 (Fig. 1b), positive gravity changes occurred in the Gulang area east of Menyuan, whereas negative gravity changes occurred to the south of Menyuan. Thus, a four-quadrant distribution of gravity changes formed that was centred at Menyuan. The gravity changes at the Menyuan earthquake epicentre were weak and close to zero. Gravity differences between the southeastern and northwestern sides of Wuwei, Gansu–Menyuan, Qinghai were greater than 90 × 10− 8 ms− 2, and the 2022 Menyuan earthquake occurred near the zero isoline of gravity change at the centre of the four-quadrant distribution.

Dynamic changes in the regional gravity field before the 2022 Ms 6.9 Menyuan earthquake (a) from October 2018 to October 2020 and (b) from October 2020 to July 2021. F1: Tuolaishan fault; F2: Lenglongling fault; F3: Jinqianghe fault; F4: Maomaoshan fault; F5: Laohushan fault; F6: Yinaocao fault; F7: Changma-Ebo fault; F8: Qilianshan northern marginal fault; F9: Tiangouqiao-Huangyangchuan fault; F10: Zhuanglanghe fault; The graph was drawn using Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) software (https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org, Version 6.5.0).

Dynamic gravity field changes before the Luding earthquake

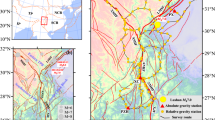

From September 2019 to September 2020 (Fig. 2a), gravity changes throughout the study area ranged from − 40 to + 70 × 10− 8 ms− 2, with a general W–E negative–positive gravity change trend. The trend of the gravity change isolines was consistent with that of the main faults in the area, thereby indicating strong tectonic activity. The study area can be divided into eastern and western regions by a boundary located along Daofu–Kangding–Jiulong. The western region exhibited gentle negative gravity changes on the western Sichuan Plateau, whereas the eastern region exhibited substantial positive gravity changes at Xiaojin, Luding, Shimian, and Mianning areas. The gravity change isoline was curved and intersected near Kangding and Luding on the Xianshuihe fault zone. The 2022 MS 6.8 Luding earthquake occurred near the turning part of the gravity change high-gradient zone.

From September 2019 to September 2021 (Fig. 2b), gravity changes throughout the study area ranged from − 60 to + 70 × 10− 8 ms− 2, and the W–E gravity change trend was negative to positive. Two local positive gravity change anomalies (maximum of 70 × 10− 8 ms− 2) were located at Jiulong and Mianning areas (south of the epicentre), as well as at Xiaojin area (north of the epicentre). Gravity change high-gradient zone were located along the Longmenshan Fault and on the Xianshuihe fault zone in Wenchuan, Ya’an, Luding, and Kangding areas. The gravity changes exhibited a four-quadrant distribution centred at Moxi and Shimian. The 2022 MS 6.8 Luding earthquake epicentre was located near the turning part of the gravity change high-gradient zone and the center of the gravity change four-quadrant distribution.

Dynamic changes in the regional gravity field before the 2022 Ms 6.8 Luding earthquake (a) from September 2019 to September 2020 and (b) from September 2019 to September 2021. F1: Longmenshan fault; F2: Xianshuihe fault; F3: Yulongxi fault; F4: Xiaojinhe fault; F5: Anninghe fault; F6: Daliangshan fault; F7: Zhaojue-Butuo fault; F8: Zemuhe fault; F9: Xiaojiang fault; The graph was drawn using Generic Mapping Tools (GMT) software (https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org, Version 6.5.0).

Menyuan earthquake epicentre prediction

In the 2021 and 2022 earthquake trend study report, the Second Crust Monitoring and Application Centre of the China Earthquake Administration made mid-term predictions of the Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake16. The prediction details are summarised in Table 1. The 2021 prediction indicated that the earthquake would occur in the Gansu Jinchang–Qinghai Qilian area. The 2022 prediction indicated that the earthquake would occur in the central or eastern Qilian Mountains.

On January 8, 2022, the MS 6.9 Menyuan earthquake (37.77° N, 101.26° E) occurred in the predicted area. The distances between the epicentres predicted in 2021 and 2022 and the actual epicentre measured by China Earthquake Networks Centre were 6 and 56 km respectively10.

The regional gravity changes from October 2018 to October 2020 (Fig. 1a) indicate that the southwestern Qilian and Menyuan areas of the Qilian Mountains underwent positive gravity changes, whereas the Shandan and Wuwei areas of the Hexi Corridor underwent negative gravity changes (difference of 60 × 10− 8 ms-2). A gravity change high-gradient zone was located along the Tuolaishan Fault and Lenglongling Fault, which changed direction near Menyuan. Based on these changes and the relationship between gravity changes and seismic activity studied by predecessors8,9, we proposed in 2020 that a strong earthquake of magnitude 6 might occur in 2021 near the Menyuan area where the gravity change high-gradient zone bends southward. The regional gravity changes from October 2020 to July 2021 further indicate that the four-quadrant gravity change distribution was centred at Menyuan, and that the gravity difference between the southeastern and northwest sides of the Menyuan–Wuwei region in Qinghai was 90 × 10− 8 ms-2. In 2021, we moved the centre of the 2022 earthquake danger zone southeastward to the intersection of the zero isoline and the Lenglongling Fault, which is near the centre of the gravity change four-quadrant distribution (Fig. 1b). The predicted magnitude did not change.

Before the 2022 MS 6.9 Menyuan earthquake, gravity change first showed a gradient zone of gravity change that was basically consistent with the strike of Tuolaishan fault and Lenglongling fault (Fig. 1a), and then exhibited a four-quadrant distribution around the earthquake epicentre (Fig. 1b), which provided a basis for the location determination and mid-term prediction of this earthquake2,9. The Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake occurred near the center of the four-quadrant and the zero isoline of gravity change.

Luding earthquake epicentre prediction

The 2021 and 2022 reports by the Second Crust Monitoring and Application Centre of the China Earthquake Administration also made accurate mid-term predictions of the 2022 Luding earthquake. The prediction details are summarised in Table 1. The 2021 prediction indicated that the earthquake would occur in the Sichuan Daofu–Yunnan Zhaotong area, whereas the 2022 prediction indicated that the earthquake would occur along the eastern Sichuan–Yunnan border (i.e., Daofu, Xiaojin, Kangding, Luding, Shimian, Jiulong, Mianning, Xichang areas).

On September 5, 2022, the MS 6.8 Luding earthquake (29.59° N, 102.08° E) occurred in the predicted area. The distances between the epicentres predicted in 2021 and 2022 and the actual epicentre were 8 and 44 km, respectively16.

The gravity changes along the eastern Sichuan–Yunnan border from September 2019 to September 2020 (Fig. 2a) indicate that gravity change high-gradient zone were located along the Xianshuihe and Yulongxi faults, with a bend near Luding. The gravity changes east of the Daofu–Kangding–Jiulong gradient zone were positive, whereas those west of the gradient zone were negative, with a maximum difference of 100 × 10− 8 ms− 2. Based on the gravity anomaly changes, we proposed in 2020 that the bend in the gravity gradient zone near Luding would be the potential earthquake epicentre in 2021, with a strong risk of a magnitude 7 earthquake in the area. However, data from September 2019 to September 2021 indicate that the area near Shimian was the centre of the four-quadrant gravity change distribution, which was bounded by the Xianshuihe and Daliangshan faults (Fig. 2b) and had a maximum gravity difference of more than 100 × 10− 8 ms− 2. Therefore, we updated our prediction in 2021 to state that an earthquake of magnitude 7 could occur in this region in 2022.

Before the 2022 MS 6.8 Luding earthquake, gravity changes first showed in a gradient zone that was consistent with the strike of the Xianshuihe tectonic belt (Fig. 2a) and then exhibited a four-quadrant distribution around the epicentral area (Fig. 2b). The 2022 Luding earthquake occurred near the centre of the four-quadrant distribution and the zero isoline of gravity change. Thus, the mobile gravity data accurately predicted the epicentre location of the 2022 Luding earthquake. The four-quadrant center of gravity change and the turning part of the high-gradient zone which is basically consistent with the strike of Xianshuihe fault are the main basis for determining the location of Luding earthquake.

In summary, both the Menyuan MS 6.9 and Luding MS 6.8 earthquakes occurred in the four-quadrant center of gravity changes. The gravity data accurately determined the epicenters of the Menyuan M6.9 and Luding M6.8 earthquakes in 202213,16.

Discussion

Earthquake is a form of tectonic activity on the earth. The preparation and occurrence of earthquakes will inevitably lead to a certain range of geophysical field changes in the source area and the surrounding area. Time-varying gravity measurements for earthquake monitoring and prediction in mainland China have been performed for more than 50 years, with consistently improved observation ranges, periods, and accuracies. We have gradually realised the capture of gravity fields before a strong earthquake, which will exhibit a gravity change four-quadrant distribution or gravity change high-gradient zones along a structural belt. Many major earthquakes were successfully mid-term predicted, such as Wenchuan MS 8.0 in 2008, Lushan MS 7.0 in 2013 and Jiuzhaigou MS 7.0 in 20173,4,5,6,17. Based on a large number of strong earthquake cases, Pre-earthquake gravity changes indicate that large-scale orderly changes (i.e. field precursors) occur in the regional gravity field, and local gravity anomalies (i.e. a source precursor) related to pre-earthquake processes are generated in the source area, and the gravity change high-gradient zones or four-quadrant distributions also occur along seismogenic zones. Strong earthquakes are prone to occur near the four-quadrant center of gravity change associated with block tectonic activity, and on the high-gradient zone of gravity change, and at the turning part of the contour line of gravity change7,8,9,12,18,19. Earthquake magnitude is also closely related to the range, amplitude, and duration of the associated gravity anomaly changes. Larger magnitude events produce larger gravity variation ranges and amplitudes near the epicentre with longer durations. The gravity change distribution is related to the specific seismogenic region, and a four-quadrant distribution is an important indicator of short-term and imminent strong earthquake occurrence2,8,19. The 2022 Menyuan and Luding earthquake epicentres were located at the centres of their respective gravity change four-quadrant distributions, thereby indicating this distribution type can be used as a reliable precursor anomaly for strong earthquakes.

The change of gravity field related to earthquake preparation is the response of the migration and change of underground material distributed at all depths of the crust20,21. The preparation of strong earthquakes is controlled by the main active fault zones in the region. Differential tectonic motions in the tectonic belt and its vicinity are usually accompanied by significant gravity field changes. The enhanced regional stress field produces density changes in media at different crustal depths (including the focal medium), as well as changes in the surface gravity over a wide range. The migration of deep crustal and mantle materials along the weak parts of a fault structure leads to pre-earthquake creep along the fault, which produces a gravity change four-quadrant distribution or gravity change high-gradient zone8,12. Strong earthquakes are likely to occur in the high-gradient zone of gravity changes and the turning part of the contour line of gravity change, which are associated with the boundary of active tectonic block. The boundary of active tectonic block is a zone with strong material change and tectonic deformation, which is easy to produce severe gravity change and accumulate stress/strain to breed earthquakes2,7,10,22. Therefore, at a specific spatiotemporal scale, the occurrence of strong earthquakes is related to the non-uniform spatiotemporal variations in the regional gravity field.

The influence of fluid factors on gravity measurements is an unavoidable issue in the computational analysis of surface gravity changes. Fluid circulation mainly includes surface water (such as rainfall, snowfall, glaciers, lakes and rivers) and deep crustal high-pressure fluid ( such as magma, deep water ). First of all, the mobile gravity measurement work is basically observed in the same month in different years, so that the observation helps to minimize the impact of seasonal water changes on gravity changes, and existing studies have shown that the effect of annual variation of rainfall is less than 5 × 10− 8 ms− 2 1,23. Zhao et al. used GLDAS surface soil water data to calculate the gravity effect of surface water changes before the Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake. The calculation shows that the gravity effect caused by the annual change of surface soil water content before the Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake is not only less than the observation accuracy of the relative gravimeter (10 × 10− 8 ms− 2 ), but also far less than the significant gravity change observed before the Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake10. This indicates that the gravity change before the Menyuan MS 6.9 earthquake reflects the result of deep material migration, not surface water change. The gravity change caused by the annual change of surface soil water near the epicenter of Luding earthquake is similar to that in the northeastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Therefore, the gravity changes observed near the epicenter before the two earthquakes are not caused by rainfall, but are geophysical phenomena related to earthquakes. Previous studies have shown that20,21, the gravity change before the earthquake may be related to the migration of deep underground fluid. Recent theoretical calculations also show that fluid intrusion at a depth of 6–10 km in the crust can produce observable gravity changes on the surface24. Therefore, we believe that when there is a fluid upwelling channel in the crust, under the action of regional stress, the fluid upwells and flows into the surrounding pre-existing or newly opened cracks, causing changes in the density of the medium in the source area, resulting in significant gravity changes in the area near the epicenter before the earthquake.

Accurate determination of an earthquake epicentre is very difficult. However, if four-quadrant gravity change distributions associated with tectonic activity can be used to delineate the potential epicentre and magnitude of a future strong earthquake, only the timing of the earthquake would be unknown, thereby improving our prediction ability. Thus, performing earthquake tracking in and around the epicentre of a potential future strong earthquake is required, which may be helpful for short-term and imminent predictions. Previous studies have indicated that strong earthquakes tend to occur in high-gradient zones between positive and negative gravity change anomalies associated with active faults, and near the centres of gravity change four-quadrant distributions1,2,7,19,25,26. Thus, related observations should be made in potentially dangerous epicentral areas and their vicinities along tectonic belts8,9,11,27. These include dense network observations (e.g. gravity, seismic, electromagnetic), which could be used to capture pre-earthquake processes in the source area, explore short-term and imminent earthquake precursors, and make short-term and imminent predictions of strong earthquakes.

We suggest that high-density absolute gravity network observations should be strengthened in epicentral areas of potential strong earthquakes in the future, particularly continuous absolute gravity observations using cold atom gravimetry (e.g. AQG, A-Grav, RAI-g, and ZAG types), to determine the potential timing of future strong earthquakes. In addition, absolute gravity observation networks with high spatial and temporal densities or relative gravity observation networks with good absolute gravity control should be established in potential high-risk areas. These networks could be used to determine the distributions of subsurface structures near epicentres in high-risk areas, extract the gravity change signals that accompany the source change during pre-earthquake processes, obtain high-precision absolute gravity changes, and analyse the variations in the gravity field during the sub-instability stage before an earthquake28,29,30. Such information could provide support for monitoring the pre-earthquake environment and processes, as well as determining strong earthquake locations accurately.

Data availability

The datasets used during this study are openly available in the repository ZENODO at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13989737.

References

Zhu, Y. Q., Zhan, F. B., Zhou, J. C., Liang, W. F. & Xu, Y. M. Gravity measurements and their variation before the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 100 (5B), 2815–2824. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120100081 (2010).

Zhu, Y. Q., Liu, F., Zhang, G. Q. & Xu, Y. M. Development and prospect of mobile gravity monitoring and earthquake forecasting in recent ten years in China. Geodesy Geodyn. 10 (6), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geog.2019.05.006 (2019).

Zhu, Y. Q., Liang, W. F. & Xu, Y. M. Medium-term prediction of MS 8.0 earthquake in Wenchuan, Sichuan by mobile gravity. Recent Developments in World Seismology, 38(7), 36–39. (2008). https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:GJZT.0.2008-07-005

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Study on dynamic change of gravity field in China continent. Chin. J. Geophys. 55 (3), 804–813. https://doi.org/10.6038/j.issn.0001-5733.2012.03.010 (2012).

Zhu, Y. Q., Wen, X. Z., Sun, H. P., Guo, S. S. & Zhao, Y. F. Gravity changes before the Lushan, Sichuan, MS =7.0 earthquake of 2013. Chin. J. Geophys. 56 (6), 1887–1894. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20130611 (2013).

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Gravity changes before the Jiuzhaigou, Sichuan, MS 7.0 earthquake of 2017. Chin. J. Geophys. 60 (10), 4124–4131. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20171037 (2017).

Zhu, Y. Q., Liang, W. F. & Zhang, S. Earthquake precursors: spatial-temporal gravity changes before the great earthquakes in the Sichuan-Yunnan area. J. Seismolog. 22 (1), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-017-9700-2 (2018).

Zhu, Y. Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, G. Q., Liu, F. & Zhao, Y. F. Gravity variations preceding the large earthquakes in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 21st century. Chin. Sci. Bull. 65 (7), 622–632. https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2019-0153 (2020).

Zhu, Y. Q., Liu, F., Zhang, G. Q., Zhao, Y. F. & Wei, S. C. Mobile gravity monitoring and earthquake prediction in China. Geomatics Inform. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 47 (6), 820–829. https://doi.org/10.13203/j.whugis20220127 (2022).

Zhao, Y. F. et al. Dynamic gravity changes before the Menyuan, Qinghai Ms 6.9 earthquake on January 8, 2022. Chin. J. Geophysic. 66 (6), 2337–2351. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2022Q0220 (2023a).

Jiang, Z. S., Ren, J. W. & Li, Z. X. Strategic countermeasures for promoting earthquake prediction research. Recent. Developments World Seismology. 35 (5), 168–173. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:GJZT.0.2005-05-030 (2005).

Shen, C. Y. et al. Monitoring of gravity field time variation and prediction of strong earthquakes in Chinese mainland. Earthq. Res. China. 36 (4), 729–743 (2020).

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Progress and prospect of the time-varying gravity in earthquake prediction in the Chinese mainland. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1124573. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1124573 (2023).

Xing, L. L., Li, H., Li, J. G., Zhang, W. M. & He, Z. T. Establishment of absolute gravity datum in CMONOC and its application. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 45 (5), 538–543. https://doi.org/10.11947/J.AGCS.2016.20140653 (2016).

Shen, C. Y. et al. The absolute gravity change in the Eastern Margin of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau before and after Yushu MS 7.1 earthquake in 2010. Progress Geophys. 27 (6), 2348–2357. https://doi.org/10.6038/j.issn.1004-2903.2012.06.010 (2012).

Zhao, Y. F. et al. Prediction of MS 6.9 Menyuan and MS 6.8 Luding earthquakes in 2022 based on gravity data. Chin. Sci. Bull. 68 (16), 2116–2123. https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2022-1055 (2023b).

Zhu, Y. Q., Xu, Y. M., Lü, Y. P. & Li, T. M. Relations between gravity variation of Longmenshan fault zone and Wenchuan MS 8.0 earthquake. Chin. J. Geophys. 2 (10), 2538–2546. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2009.10.012 (2009).

Zhang, J. & Sun, B. C. Discussion on gravity anomaly and anomaly mechanism before Zhangbei MS 6.2 earthquake. Earthquake. 21 (2), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3274.2001.02.012 (2001).

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Gravity changes before the Menyuan, Qinghai MS 6.4 earthquake of 2016. Chin. J. Geophys. 59 (10), 3744–3752. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20161019 (2016).

Chen, S., Liu, M. & Xing, L. L. Gravity increase before the 2015 MW 7.8 Nepal earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 111–117 (2016).

Chen, Y. T., Gu, H. D. & Lu Variations of gravity before and after the Haicheng earthquake,1975, and the Tangshan earthquake, 1976. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 18, 330–338 (1979).

Zhan, F. B. et al. Gravity changes before large earthquakes in China: 1998–2005. Geo-spatial Inform. Sci. 14 (1), 1–9 (2011).

Yue, J. L. et al. Study of groundwater settlement by absolute gravity measurement. Sci. Surveying Mapp. 35 (02), 18–20. https://doi.org/10.16251/j.cnki.1009-2307.2010.02.010 (2010).

Liu, X., Chen, S. & Xing, H. Gravity changes caused by crustal fluids invasion: a perspective from finite element modeling. Tectonophysics. 833, 229335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229335 (2022).

Fu, G. Y. et al. Bouguer gravity anomaly and Isostasy at Western Sichuan Basin revealed by new gravity surveys. J. Geophys. Research:Solid Earth. 119 (4), 3925–3938. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011033 (2014).

Shen, C. Y. et al. Dynamic variations of gravity and the preparation process of the Wenchuan MS 8.0 earthquake. Chin. J. Geophys. 52 (10), 2547–2557. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0001-5733.2009.10.013 (2009).

Jiang, Z. S., Zhang, X., Zhu, Y. Q., Zhang, X. L. & Wang, S. X. Regional tectonic deformation background before the MS 8.1 earthquake in the west of the Kunlun Mountains Pass. Sci. China (Series D). 33 (S1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-7240.2003.z1.018 (2003).

Ma, J. & Guo, Y. S. Accelerated synergism prior to fault instability: evidence from laboratory experiments and an earthquake case. Seismology Geol. 36 (3), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0253-4967.2014.03.001 (2014).

Ma, J. On whether earthquake precursors help for prediction do exist [J]. Chin. Sci. Bull. 61 (Z1), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1360/n972015 (2016).

Guo, S. S. et al. Gravity evidence of meta-instable state before the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Seismology Geol. 43 (6), 1368–1380. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0253-4967.2021.06.002 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the field gravity observers of the China Earthquake Administration for their hard work, which provided reliable data for this paper; This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42374104, No.41874092). The authors express their appreciation to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42374104, No.41874092) for the financial support of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ and XY both contributed to topic selection, writing, and editing of the manuscript. YZ and SW contributed to the discussion section, data processing and review and editing of the manuscript. GZ and FL contributed to drawing, review, and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Yang, X., Zhao, Y. et al. Accurate prediction of the 2022 MS 6.9 Menyuan and MS 6.8 Luding earthquake epicentres. Sci Rep 14, 29137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79091-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79091-x