Abstract

Natural products, with their extensive chemical diversity, distinctive biological activities, and vast reservoirs, provide a robust foundation for advancing cancer therapeutics. A comprehensive phytochemical investigation of the skins from Bufo bufo gargarizans afforded two new bufadienolide derivatives identified as bufalactamides A and B (1–2), along with six known compounds: argentinogenin (3), desacetylcinobufagin (4), desacetylcinobufaginol (5), cinobufaginol (6), bufalin (7) and gamabufalin (8). The structural elucidation of these compounds was meticulously carried out by analyses of spectroscopic data (1D and 2D NMR, HR-ESIMS), and comparison with the literature data. Plausible biosynthetic pathways for the new compounds were also discussed. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of the compounds was investigated using various cancer cell lines, including lung cancer (A549), colon cancer (HCT-116), liver cancer (SK-Hep-1), and ovarian cancer (SKOV3). Our research findings indicated that compounds 3, and 6–8 exhibit potent cytotoxic activity (IC50 < 2.5 µM). In contrast, compounds 4 and 5 display moderate cytotoxic activity (IC50 < 50 µM) while compounds 1 and 2 show no cytotoxic activity (IC50 > 100 µM). From this data, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the structure-activity relationships among these compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer poses a significant threat to global human health1. Among various non-surgical treatment methods, systemic chemotherapy is a crucial modality. However, due to changes in the biological characteristics of tumor cells and disturbances in the metabolic functions of various organs, many tumor cells have developed resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, which diminishes the efficacy of chemotherapy2. Consequently, developing novel anticancer drugs has become an urgent and vital task.

Historically, natural products (NPs) have been pivotal in drug discovery, specially in cancer research3. NPs offer unique advantages and developmental potential in various aspects such as inhibiting tumor cell proliferation4, inhibiting migratory and invasive5, inducing tumor cell apoptosis and differentiation6, enhancing immunity7, and regulating autophagy8. Literature reveals that two-thirds of antitumor drugs originate from natural products or their derivatives9, including notable examples like camptothecin, paclitaxel, resveratrol and podophyllotoxin10,11,12,13. Therefore, screening for effective and low-toxicity antitumor drugs from natural products is a valid approach and strategy.

In China, the Bufo bufo gargarizans and Bufo melanostictus are vital sources for traditional medicine. Through appropriate processing, medicinal components like “Chanpi” and “Chansu” are extracted. Modern pharmacological studies demonstrate that toad-based medicinal ingredients possesses notable anti-tumor and antiviral properties, especially effective in the treatment of heart failure14,15,16. As a result, it is extensively used in treating various clinical conditions including hepatitis B, chronic bronchitis, sore throats, and furunculosis17. A prominent example is the Huachansu Injection, primarily derived from toad skin, which has demonstrated promising results in cancer treatment18. The chemical composition of “Chanpi” is complex and diverse, mainly consisting of bufadienolides19, indole alkaloids20, and bufocyclopeptides21. Among these, bufadienolides are considered the primary pharmacological components due to their significant antitumor effects.

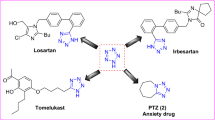

As part of a program to assess the chemical diversity and biological activity of traditional Chinese medicines, our investigation on “Chanpi” led to discovery of various new constituents with different biological activities22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Herein, we report the isolation, structure elucidation, postulated biogenetic pathway, and bioactivity assay of two new bufalactamides A and B (1–2), which possess an unprecedented skeleton, along with six known analogs, identified as argentinogenin (3)33, desacetylcinobufagin (4)34, desacetylcinobufaginol (5)35, and cinobufaginol (6)35, bufalin (7)36 and gamabufalin (8)37 (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

General23,24,25

UV spectra were acquired on a Shimadzu UV-2700 Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). IR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Tensor-27 microscope instrument (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) using KBr pellets. NMR spectra were recorded at 500 MHz for 1H and 125 MHz for 13C, respectively, on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin AG, Fallanden, Switzerland) in MeOH-d4 with solvent peaks used as references. Mass spectra were recorded on a LCMS-IT-TOF (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Column chromatography (CC) was carried out on macroporous adsorbent resin (HPD-110, Cangzhou Bon Absorber Technology Co. Ltd, Cangzhou, China), silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc. Qingdao, China), sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden), CHP 20P (Mitsubishi Chemical Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and reversed phase C-18 silica gel (W. R. Grace & Co., Maryland, USA). HPLC separation was performed on an instrument equipped with a Gilson ChemStation for LC system, and an Agilent semipreparative column (250 × 10 mm i.d.) packed with C18 reversed phase silica gel (5 μm). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on glass precoated silica gel GF254 plates (Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc). Spots were visualized under UV light or by spraying with 10% H2SO4 in 90% EtOH followed by heating. Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were purchased from commercially available sources and used without further purification.

Animal material

The skin samples of Bufo bufo gargarizans were obtained from Anguo, Hebei Province, in July 2020 and authenticated by Dr. Changwei Song. The acquisition of these animal materials was authorized by the respective farmer, adhering to institutional regulations and ethical guidelines. A voucher specimen (ID-TS-001) has been archived at the Guizhou Provincial Key Laboratory for Tumor Prevention and Treatment with Herbal Medicines, affiliated with Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China.” Experimental animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of propofol (concentration 10 g/L, dosage 1 ml/100 g; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and subsequently euthanized followed by dissection.

Ethics statement

This study’s animal experiments strictly adhere to the ARRIVE guidelines, and all experimental protocols have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zunyi Medical University. Specifically, the animal experiments were conducted under standard conditions and in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Animal Care Committee of Zunyi Medical University (ZMU21-2203-166).

Extraction and isolation23

The air-dried skins of Bufo bufo gargarizans (20.0 kg) were pulverized and extracted with 95% EtOH. The crude extract (1.0 kg) was then suspended in H2O and successively partitioned into petroleum ether and ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate fraction (200 g) was separated by silica gel column chromatography (CC) (PET–EtOAc, 100:1–0:100, v/v) to yield fractions Fr.1 ~ Fr.16. Fraction 12 (26 g) was subjected to CC over ODS for further separation, using a MeOH/H2O gradient elution (V: V, 1:1 to 1:0), to yield subfractions Fr.12.1 ~ Fr.12.6. Fr.12.3 (2.8 g) was then purified by preparative HPLC on an XB-C8 column (64% MeOH in H2O, 8 ml/min), resulting in Fr.12.3.1 ~ Fr.12.3.6. Among these, Fr.12.3.2 (66 mg) was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC (23% MeCN in H2O + 0.5% acetic acid, 2.5 mL/min), yielding 1 (3.3 mg, tR=86 min), and Fr.12.3.3 (45 mg) was purified by semi-preparative HPLC (30% MeCN in H2O + 0.5% acetic acid, 2.5 mL/min), yielding 4 (5.4 mg, tR=61 min) and 7 (6.5 mg, tR=48 min). Fr.12.2 (1.3 g) was separated by CC over silica gel (PET–EtOAc, 1:1–0:100, v/v) to yield fractions Fr.12.2.1 ~ Fr.12.2.16. Subfraction Fr.12.2.7 (328 mg) was separated by CC over Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give 8 (12 mg). Subfraction Fr.12.2.7 (0.5 g) was separated by CC over ODS with a gradient of increasing MeOH (45–100%) in H2O to give Fr.12.2.7.1 ~ Fr.12.2.7.9, of which Fr.12.2.7.5 (87 mg) was purified by HPLC (54% MeOH in H2O, 2.5 ml/min) to yield 5 (2.2 mg, tR = 13 min) and 6 (2.2 mg, tR = 34 min). Fr.10 (14.8 g) was separated by CC over Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give Fr.10.1 ~ Fr.10.10, of which Fr.10.4 (2.48 g) was subjected silica gel CC (DCM–MeOH, 20:1, v/v) to yield Fr.10.4.1 ~ Fr.10.4.6. Subfraction Fr.10.4.4 (1.88 g) was separated by CC over ODS with a gradient of increasing MeOH (60–100%) in H2O to give Fr.10.4.4.1 ~ Fr.10.4.4.6, of which Fr.10.4.4.5 (46 mg) was separated by CC over Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give 2 (1.8 mg). Fr.10.4.4.2 (324 mg) was separated by CC over Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give Fr.10.4.4.2.1 ~ Fr.10.4.4.2.9. Then, subfraction Fr.10.4.4.2.5 (83 mg) was purified by HPLC (56% MeOH in H2O, 5 ml/min) to yield 3 (4.7 mg, tR = 67 min).

Bufalactamide A (1)

White amorphous powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 203 (4.05), 288 (5.76) nm; IR νmax 3408, 2938, 1664, 1470, 1384, 1270, 1174, 1100, 1062, 1035, 940 cm− 1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) spectral data, see Table 1; ESIMS: m/z 438 [M + Na]+ and 853 [2 M + Na]+; HR-ESI-MS: m/z 438.2254 [M + Na]+ (calculated for C24H33NO5Na, 438.2251).

Bufalactamide B (2)

White amorphous powder; UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 205 (2.39), 281 (1.04) nm; IR νmax 3437, 2932, 1647, 1452, 1382, 1308, 1181, 1095, 1077, 1127, 944 cm− 1; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3OD, 125 MHz) spectral data, see Table 1; ESIMS: m/z 388 [M + H]+; HR-ESI-MS at m/z 410.2663 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C24H37NO3Na, 410.2666).

Cell cultures31,32

Human lung cancer (A549), colon cancer (HCT-116), liver cancer (SK-Hep-1), and ovarian cancer (SKOV3) cell lines were purchased from Shanghai Jikai Gene Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. These tumor cell lines were removed from liquid nitrogen and rapidly thawed by shaking in a 37 °C water bath. Subsequently, the cells were transferred into Petri dishes containing RPMI-1640 complete medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (including 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin) and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The culture medium was replaced after 8–12 h. Upon reaching approximately 75-85% confluence at the bottom of the culture dish, the culture medium was discarded, and the cells were rinsed twice with PBS. Then, 0.25% trypsin was added for digestion until 75-85% of the cells became rounded and brighter. Fresh culture medium was added to stop the digestion. The cells were gently pipetted and transferred into a 10 mL centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in culture medium. They were then subcultured at a ratio of 1:3 or used for subsequent experiments.

Cell viability testing using SRB38

To assess cytotoxic activity, lung cancer (A549), colon cancer (HCT-116), liver cancer (SK-Hep-1), and ovarian cancer (SKOV3) cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 8 × 103 cells per well and cultured under conditions of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After an incubation period of 24 h, the 96-well plates were removed from the incubator, and 200 µL of culture medium containing the test compounds were added to each well for an additional 24-hour incubation, with each group replicated three times. Following incubation, the cultures were fixed by adding pre-chilled 10% TCA and incubating at 4 °C for 2 h. The TCA fixative was then discarded, and the wells were washed five times with deionized water. Excess liquid was shaken off, and the plates were air-dried at room temperature. After drying, 100 µL of 0.4% SRB dye were added to each well and left to stand at room temperature for 20 min. Unbound SRB dye was then rinsed off with 0.1% acetic acid solution, repeated five times, and the plates were allowed to dry at room temperature. Subsequently, 100 µL of 10 mM Tris buffer solution were added to each well to facilitate dissolution. The plates were then analyzed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader to calculate the IC50 values.

Results and discussion

Phytochemical investigation ofBufo bufo gargarizans

Utilizing various chromatographic techniques such as silica gel column chromatography, gel column chromatography, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), in conjunction with spectroscopic methods including UV, IR, MS, and NMR, two rare new compounds were isolated and identified for the first time from the skin of Bufo gargarizans. These new compounds are characterized by a δ-lactam unit and possess a 14,21-oxybridge structural feature. Furthermore, six known bufadienolide compounds were also successfully obtained.

Compound 1 was isolated as a white amorphous powder with [α]20D -22.6 (c 0.06, MeOH). The ESI-MS analysis revealed quasi-molecular ion peaks at m/z 438 [M + Na]+ and 853 [2 M + Na]+. The HR-ESI-MS analysis showed a peak at m/z 438.2254 [M + Na]+ (calculated for C24H33NO5Na, 438.2251), indicating the molecular composition of C24H33NO5. The IR spectrum exhibited the characteristic absorption of hydroxyl and carbonyl group at 3408 and 1665 cm− 1, respectively. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra indicated the presence of a δ-lactam moiety [δH 1.84 (m, H-20), 4.64 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-21), 1.64 (m, H-22a), 1.58(m, H-22b), 2.44 (m, H-23a), 2.42 (m, H-23b); δC 38.8 (C-20), 82.0 (C-21), 22.2 (C-22), 32.2 (C-23), 174.8 (C-24)]; two angular methyl groups [δH 1.18 (s, Me-18), δC 14.1 and δH 1.29 (s, Me-19), δC 27.5]; an oxygenated methine [δH 3.97 (m, H-3), δC 67.3]; an oxygenated quaternary carbon [δC 86.7 (C-14)]; a ketone quaternary carbon [δC 200.0 (C-12)]; and two unsaturated quaternary carbons [δC 133.2 (C-9) and 142.1 (C-11)]. Based on this spectroscopic data, and considering the previous isolation and identification of similar compounds from B. melanosticus and B. bufo gargarizans, this compound is preliminarily identified as a bufadienolide analogue.

In the HMBC spectrum (Fig. 2), correlations were observed between H-21 and C-17, C-22, and C-24, suggesting the δ-lactam moiety at the C-17 position. The HMBC spectrum also showed correlations between H-21 and C-14 (Fig. S9 and S25 in supplementary material), H-18 and C-12, C-14, and C-17, indicating an oxygen bridge between C-14 and C-21. Furthermore, compared to the chemical shift value of 83.4 ppm for C-14 in compound 3, the C-14 chemical shift in compound 1 is 86.7 ppm, representing a downfield shift of 3.3 ppm, which further suggests that C-14 may have undergone etherification (Fig. S26 in supplementary material). Additionally, correlations between H-8 and C-11, as well as H-19 and C-9, suggest the formation of an unsaturated double bond between C-11 and C-12. Moreover, connections between H-2 and H-5 with C-3 indicate a hydroxyl substitution at the C-3 position. To satisfy the molecular weight and two quaternary carbon double bonds, an additional hydroxyl group must be substituted at the C-11 position. Consequently, the planar structure of compound 1 is shown in Fig. 2. In the NOESY spectrum (Fig. 3), correlations were observed between H-4a with H-3 and H-6a, H-6a with H-17, suggesting an α configuration for these protons. Simultaneously, correlations were observed between H-19 with H-5 and H-18, as well as H-18 with H-21, indicating a β configuration for these protons. Therefore, the structure of compound 1 was determined and named bufalactamide A.

Compound 2 was isolated as a white amorphous powder with [α]20D -27.5 (c 0.2, MeOH), and exhibited the molecular formula of C24H37NO3 by the HR-ESI-MS at m/z 410.2663 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C24H37NO3Na, 410.2666). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra indicated the presence of a δ-lactam moiety, two angular methyl groups, an oxygenated methine, and an oxygenated quaternary carbon, suggesting it to be an analogue of bufalactamide A. The planar structure of compound 2 was confirmed by the HMBC spectrum (Fig. 2). Although no long-range correlation between H-21 and C-14 was observed in the HMBC spectrum, an in-depth analysis of the NMR data for compound 2 was conducted, with comparisons made to compounds 7 and 1, incorporating both proton and carbon spectra. The chemical shift value for C-14 in compound 2 was determined to be 89.2 ppm, indicating a downfield shift of 2.9 ppm relative to the 86.3 ppm observed for C-14 in compound 7 (Fig. S27 in supplementary material). This discrepancy suggests the potential etherification at the C-14 position in compound 2. Additionally, a high degree of similarity was noted in the chemical shifts at C-21 and H-21, along with their respective coupling constants, when compound 2 was compared with compound 1 (Figs. S28 and S29 in supplementary material). These findings indicated that compounds 2 and 1 likely share a similar chemical environment in the δ-lactam region, thereby ruling out the presence of a free hydroxyl group at the C-21 position. In the NOESY spectrum (Fig. 3), correlations were observed between H-2a with H-3 and H-9, H-17 with H-9 and H-21, suggesting α configuration for these protons. Simultaneously, correlations were observed between H-8 with H-18 and H-19 indicating β configuration for these protons. Therefore, the structure of compound 1 was determined and named bufalactamide B.

By comparing the spectroscopic data with the reported data in the corresponding literature, the known compounds were identified as argentinogenin (3)33, desacetylcinobufagin (4)34, desacetylcinobufaginol (5)35, and cinobufaginol (6)35, bufalin (7)36 and gamabufalin (8)37.

The plausible biosynthetic pathway of 1 and 2

Bufalactamide A (1) and Bufalactamide B (2) possess a unique 14,21-oxygen bridge structure not yet been identified in natural products. We propose a plausible biosynthetic pathway. The biosynthetic precursor of 1 is proposed to be argentinogenin (compound 3). Under enzymatic catalysis, NH3 acts as a nucleophile to attack the lactone ring of 3, forming intermediate c. This intermediate then undergoes a lactone ring-opening reaction (d) followed by a condensation reaction leading to e. Subsequently, e undergoes a dehydration reaction to yield f. The unsaturated six-membered amide ring in f is then reduced via hydrogenation reaction, converting it into intermediate g. g interacts with h through enamine and imine tautomerization. Based on this, a selective nucleophilic addition reaction occurs between the hydroxyl group at the C-14 position and the unsaturated double bond at the C-21 position of h, ultimately resulting in the formation of 1 (Scheme 1A). For compound 2, the biosynthetic precursor is proposed to be bufalin (compound 7), with its putative biosynthetic pathway mirroring that of 1, as detailed in (Scheme 1B).

Cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxic effects of compounds 1–8 were examined using the SRB method. The estimated IC50 values were given in Table 2 and the percent vitality graph according to the SRB results were given in Fig. 4. According to the results, except for the new compounds 1 and 2, the other six compounds displayed varying degrees of cytotoxic activity against lung (A549), colon (HCT-116), liver (SK-Hep-1), and ovarian (SKOV3) cancer cells. Specifically, compounds 3, and 6–8 showed significant IC50 on A549, HCT-116, SK-Hep-1, and SKOV3 cells as 0.2 ± 0.04, 0.06 ± 0.04, 0.1 ± 0.05, and 0.64 ± 0.56 µM for compound 3, 2.17 ± 1.89, 0.53 ± 0.14, 1.33 ± 1.05, and 1.76 ± 0.72 µM for compound 6, 0.03 ± 0.001, 1.09 ± 1.15, 0.07 ± 0.09, and 1.76 ± 1.08 µM for compound 7, and 0.17 ± 0.15, 0.06 ± 0.05, 0.1 ± 0.09, and 0.45 ± 0.26 µM for compound 8. Compounds 4 and 5 showed moderate cytotoxic activity on the mentioned cells, with IC50 on A549, HCT-116, SK-Hep-1, and SKOV3 of 22.29 ± 4.09, 10.67 ± 2.54, 11.26 ± 6.62, and 19.39 ± 0.63 µM for 4, and 22.96 ± 0.49, 18.92 ± 4.29, 33.73 ± 14.63, and 41.05 ± 3.73 µM for 5. These findings align with literature reports on the antitumor activity of bufadienolide compounds39. However, it is regrettable that the new compounds 1 and 2 did not exhibit cytotoxic activity.

The anticancer activities of the eight pure compounds (1–8) using SRB assay on lung cancer, colon cancer, liver cancer, and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer cells lines A549 (A), HCT-116 (B), SK-Hep-1 (C) and SKOV3 (D). The graphs show the percentage of survival of A549, HCT-116, SK-Hep-1 and SKOV3 treated cells relative to matching solvent-treated cells. All experiments were performed at least three times. *p < 0.05.

Structure-activity relationship (SAR)

In our hypothesized biosynthetic pathway, compounds 1 and 2 are likely derived from compounds 3 and 7, respectively. However, the significant disparity in activity suggests that the amide ring at the C-17 position or the presence of 14,21-oxybridge is not favorable for the activity. Compound 6, with a 16-acetyl group showed stronger activity than compound 5, which has a 16-hydroxyl group, demonstrating that 16-acetyl is a favorite factor to increase the cytotoxicity. By comparing the structural differences between compounds 4 and 5, it is evident that the presence of a 19-hydroxyl group may lead to a reduction in activity. Compared to compound 8, compound 7 lacks an 11-hydroxyl, while compound 3 possesses an additional Δ9,11-double bond and a 12-carbonyl. Despite these variations, the three compounds exhibit comparable cytotoxic activities, suggesting that the 11-hydroxyl, 12-carbonyl, and Δ9,11-double bond moieties may not be crucial pharmacophores for the antitumor activity of bufadienolide compounds.

In conclusion, the structural requirements of bufadienolide derivatives to enhance their cytotoxic activity against tested cell lines are as follows (Fig. 5): (a) The δ-lactone moiety at position C-17 is essential for activity and as a basic pharmacophore. Notably, our investigations have demonstrated that the incorporation of the δ-lactam moiety directly diminishes the cytotoxic efficacy of these compounds. (b) The 14β-hydroxy and 14,15-epoxy functional groups are necessary. Generally, derivatives with a 14β-hydroxy substitution exhibit enhanced activity compared to their 14,15-epoxy counterparts. (c) While neither the 16β-acetoxyl nor the 16β-hydroxyl groups are essential for activity, the 16β-acetoxyl substitution results in increased activity compared to the 16β-hydroxyl counterpart.

Conclusion

This study afforded structurally diverse bufadienolides from the skins of bufo bufo gargarizans, including two new compounds (1–2), which are uniquely characterized by the presence of a lactam and a complex 14,21-oxygen bridge. Additionally, six known compounds (3–8) were also isolated. All the isolates were evaluated for their cytotoxic activities against A549, HCT-116, SK-Hep-1, and SKOV3 cells. Our results demonstrated that, with the exception of compounds 1 and 2, all other compounds displayed varying magnitudes of antiproliferative activity against tumor cells. Preliminary structure-activity relationship studies indicated that the δ-lactone moiety at position C-17 of bufadienolides is crucial for activity and serves as a fundamental pharmacophore. Additionally, we found that the 14β-hydroxy substitution demonstrated enhanced activity compared to its 14,15-epoxy analogs. Consistently, the 16β-acetoxyl substitution led to increased activity relative to the 16β-hydroxyl counterpart. Although compounds 1 and 2 were inactive in the preliminary assay, their distinctive drug-like skeletons present novel structural features. Consequently, we proposed a plausible biosynthetic pathway for these two compounds. The plausible biosynthetic pathway provides a clue for further studies of biomimetic and total synthesis, as well as the biosynthesis of the diverse bufadienolides from Bufo bufo gargarizans. Future research should thoroughly investigate the anticancer mechanisms of action for these isolated compounds at the cellular level. Concurrently, it is paramount to assess their potential toxicity and side effects in vivo. This process is crucial for determining the clinical application prospects of these compounds.

Data availability

Data generated or analyzed during the study are included in the Supplementary Information. The data used in this current study are available from the corresponding authors at a reasonable request.

References

Wang, Y. et al. Overcoming cancer chemotherapy resistance by the induction of ferroptosis. Drug Resist. Updat 66, 100916 (2023).

Wei, G., Wang, Y., Yang, G., Wang, Y. & Ju, R. Recent progress in nanomedicine for enhanced cancer chemotherapy. Theranostics 11, 6370–6392 (2021).

Atanasov, A. G., Zotchev, S. B. & Dirsch, V. M. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 200–216 (2021).

Liu, F. J. et al. Revealing active components and action mechanism of fritillariae bulbus against non-small cell lung cancer through spectrum-effect relationship and proteomics. Phytomedicine 110, 154635 (2023).

Wang, X., Sun, Y. Y., Qu, F. Z., Su, G. Y. & Zhao, Y. Q. 4-XL-PPD, a novel ginsenoside derivative, as potential therapeutic agents for gastric cancer shows anti-cancer activity via inducing cell apoptosis medicated generation of reactive oxygen species and inhibiting migratory and invasive. Biomed. Pharmacother. 118, 108589 (2019).

Park, K. R., Lee, H., Kim, S. H. & Yun, H. M. Paeoniflorigenone regulates apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis to induce anti-cancer bioactivities in human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J. Ethnopharmacol. 288, 115000 (2022).

Song, L. et al. Icariin-induced inhibition of SIRT6/NF-κB triggers redox mediated apoptosis and enhances anti-tumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 111, 4242–4256 (2020).

Yin, Q. et al. Ginsenoside CK induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer hela cells by regulating autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Food Funct. 12, 5301–5316 (2021).

Elmaidomy, A. H. et al. New cytotoxic dammarane type saponins from Ziziphus spina-christi. Sci. Rep. 13, 20612 (2023).

Wang, X., Zhuang, Y., Wang, Y., Jiang, M. & Yao, L. The recent developments of camptothecin and its derivatives as potential anti-tumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 260, 115710 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Paclitaxel promotes mTOR signaling-mediated apoptosis in esophageal cancer cells by targeting MUC20. Thorac. Cancer 14, 3089–3096 (2023).

Gao, X. et al. Resveratrol restrains colorectal cancer metastasis by regulating miR-125b-5p/TRAF6 signaling axis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 14, 2390–2407 (2024).

Xiang, C. et al. Podophyllotoxin-loaded PEGylated E-selectin peptide conjugate targeted cancer site to enhance tumor inhibition and reduce side effect. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 260, 115780 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. Hellebrigenin anti-pancreatic cancer effects based on apoptosis and autophage. Peer J. 8, e9011 (2020).

Zhao, J. Z. et al. Traditional Chinese medicine bufalin inhibits infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e0501622 (2024).

Ruan, L., Song, Z. & Jiang, R. 3α-Hydroxybufadienolides in Bufo gallbladders: Structural insights and biotransformation. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 14, 19 (2024).

Editorial Committee of the Administration Bureau of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Chinese Ateria Medica (Zhonghua Bencao)Vol. 6, pp. 360–362 (Shanghai Science and Technology, 1999).

Wang, Y., Zhang, A., Li, Q. & Liu, C. Modulating pancreatic cancer microenvironment: the efficacy of huachansu in mouse models via TGF-β/Smad pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 326, 117872 (2024).

Li, H., Zhang, L., Wang, S., Deng, Y. & Jin, X. Two new bufotoxins from the skin of Bufo bufo gargarizans. Chin. Chem. Lett. 24, 731–733 (2013).

Dai, Y. H. et al. A new indole alkaloid from the toad venom of Bufo bufo gargarizans. Molecules 21, 349 (2016).

Cao, X., Wang, D., Wang, N., Dai, Y. & Cui, Z. Water-soluble constitutions from the skin of Bufo bufo gargarizans Cantor. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 7, 181–183 (2009).

Wang, M. et al. Arenobufagin inhibits lung metastasis of colorectal cancer by targeting c-MYC/Nrf2 axis. Phytomedicine 127, 155391 (2024).

Meng, L. et al. Bufogarlides A-C, three new bufadienolides with ∆14,15 double bond from the skins of Bufo bufo gargarizans. Nat. Prod. Res. 38, 470–476 (2024).

Meng, L. et al. Bufadienolides from the skins of Bufo melanosticus and their cytotoxic activity. Phytochem. Lett. 31, 73–77 (2019).

Meng, L. et al. Two new 19-hydroxy bufadienolides with cytotoxic activity from the skins of Bufo melanosticus. Nat. Prod. Res. 35, 4894–4900 (2021).

Meng, L., Li, C., Song, C., Li, S. & Liu, Y. Chemical constituents from Bufo melanosticus skins. Chin. Tradit Pat. Med. 45, 1172–1176 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. Chemical constituents from the skins of Bufo bufo gargarizans and their cytotoxic activities. Chin. Tradit Pat. Med. 45, 3622–3626 (2023).

Yu, C. et al. Research progress on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Bofonis Corium. Chin. Tradit Herb. Drugs 52, 1206–1220 (2021).

Jiang, N. et al. Gamabufotalin inhibits colitis-associated colorectal cancer by suppressing transcription factor STAT3. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 966, 176372 (2024).

Pan, F. et al. Six bufadienolides derivatives are the main active substance against human colorectal cancer HCT116 cells of Huachansu injection. Pharmacol. Res. - Mod. Chin. Med. 10, (2024).

Li, S. et al. 3-epi-bufotalin suppresses the proliferation in colorectal cancer cells through the inhibition of the JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Biocell 46, 2425–2432 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Hellebrigenin induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through induction of excessive reactive oxygen species. Biocell 45, 943–951 (2021).

Li, B. et al. Bufadienolides with cytotoxic activity from the skins of. Bufo bufo gargarizans Fitoterapia 105, 7–15 (2015).

Ye, M., Ning, L., Zhan, J., Guo, H. & Guo, D. Biotransformation of cinobufagin by cell suspension cultures of Catharanthus roseus and Platycodon grandiflorum. J. Mol. Catal. B-Ezym 22, 89–95 (2003).

Kamano, Y., Nogawa, T., Yamashita, A. & Pettit, G. R. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shift assignments for thirteen bufadienolides isolated from the traditional Chinese drug Ch’an Su. ChemPlusChem 66, 1841–1848 (2001).

Kamalakkannan, V., Salim, A. A. & Capon, R. J. Microbiome-mediated biotransformation of cane toad bufagenins. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 2012–2017 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Biotransformation of bufadienolides by cell suspension cultures of Saussurea involucrata. Phytochemistry 72, 1779–1785 (2011).

Vichai, V. & Kirtikara, K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1112–1116 (2006).

Liu, J. et al. Anti-tumor effects and 3D-quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis of bufadienolides from toad venom. Fitoterapia 134, 362–371 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Foundation of Guizhou Province (QKHJC-ZK[2024]YB273), Science & Technology Plan of Zunyi (ZSKHHZ[2023]168), and the Xin Miao Funding of Zunyi Medical University (QKPTRC[2021]1350-004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M. conceptualized and designed the study. L.M. and Q.C. aided in acquiring and analyzing data, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. Q.C., X.D., H.L., C.L., X.Z., N.J. and Y.X. participated in experiments and the data analysis. L.M., Q.C. and X.D. write the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, L., Cao, Q., Du, X. et al. Structurally diverse bufadienolides from the skins of Bufo bufo gargarizans and their cytotoxicity. Sci Rep 14, 27344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79194-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79194-5