Abstract

Nuclear explosion in a densely populated area is the worst that can happen to any country in the world due to enormous loss of life, property and severe economic damage. Nuclear explosions immediately cause radiological damage and destruction of infrastructure. This hydro-magnetic shock propagation due to blast gives rise to simultaneous signals around the world. The effect of shockwave from nuclear explosion is an area that can be used to handle post and pre-disaster from nuclear explosion. This study focuses on the effects of shockwave on solid objects oriented in different formation. Experiments conducted in a horizontally placed shock tube and a solid object holder on the floor of the test section. These solid objects placed inside the test section of a shock tube collided with a planner shock wave which was generated by rupturing a diaphragm of different thickness. Four high speed pressure transducers strategically placed at different locations of this shock tube were used to characterize the blasts as well as interaction with the samples. A high-speed Kronos and Phantom camera were used to record the exact moment of interaction to characterize the solid objects under the impact of different shock waves. Representative results of these experiments are reported here along with review of previous work done in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclear explosion in a densely populated area is the worst that can happen to any country in the world due to enormous loss of life, property and severe economic damage. Nuclear explosions immediately cause radiological damage and destruction of infrastructure that can be used for response to such a threat and disaster. Even though cold war is over the threat of a nuclear explosion is not over as more and more nations are gaining access to nuclear weapons and it is very important how local states and communities are prepared to respond a nuclear detonation to maximize the preservation of life in the event of an urban nuclear detonation (National security staff of interagency policy coordination sub-committee1.

Since the last and only use of nuclear weapons the world has focused a lot on the radiation effects. After a nuclear explosion most of the damage happens within 60 min of the explosion. About 90% of the energy released in the form of blast, thermal and radiation energy. As shown in Fig. 1 blast or shock wave is responsible for half of total damage from nuclear explosion. A study was also done on the impact area from the detonation center. As the distance from the epicenter of the explosion increases effects of blast and thermal energy reduces so as initial radiation effects. Residual radiation effects may spread in a vast area and will last for multiple generations. Based on the damage there can be several zones even though there are no clear boundaries among them. Light damage (LD) zone is defined by broken windows and easily managed injuries; the moderate damage (MD) zone by significant building damage, rubble, downed utility lines and some downed poles, overturned automobiles, fires, and serious injuries; and the severe damage (SD) zone by destroyed infrastructure and high radiation levels resulting in unlikely survival of victims2.

Source: Effects of nuclear explosion2.

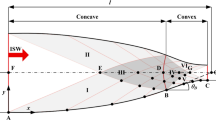

The first effect of nuclear explosion is the fireball or mushroom cloud, and destruction is triggered from this explosion. The second event is radioactive cloud which is formed by condensation of vaporized particles as the fireball progresses and it contains debris, radiation fallout is a common term used for this. The third stage is air blast or shockwave which generates immediately after explosion and moves outward from the fireball. After 1 min of a 1 Mt explosion shock front is 3 miles from the center and earth surface also reflects this wave which merges with original eave to create Mach wave2.

The guidance for emergency planner aims to save maximum amount of life and infrastructure like shelter, hospitals and communication to improve the management of disaster. Studying and understanding of how shockwave interacts with solid structure will be very crucial to identify and develop suitable structure and materials in case of a nuclear disaster. A shock tube can generate shockwaves of different Mach numbers and can be used to study how solid bodies interact with a shock wave. Unlike earlier studies described in the next section, the goal of the present work is to develop diagnostics for laboratory experiments that can produce quantitative results to provide insights into similar phenomena manifesting themselves at much larger scales, leading both to better understanding of the relevant physics and to higher-quality benchmarks for numerical models.

Literature review

A shock tube is a long tube, in a simple form enclosed at two ends separated into two sections by a diaphragm creating two zones at the initial stage—driver section and driven section. The driver side contains gas at higher pressure (called driver gas, normally inert gas or compressed air) and driven side also containing gas at a much lower pressure (called driven gas). As the diaphragm bursts, a shock, slip surface, and expansion waves propagate through the driven portion of the tube. Of particular interest to us in the context of this study is the interaction of the initial shock formed by the rupture of the diaphragm with objects downstream of the shock front—similar to a blast wave from an explosion in an urban environment.

As this shock wave propagates, it causes a nearly instantaneous increase in both temperature and pressure behind the shock wave front, and this occurs as the incident shock travels down the driven section. When the incident shock strikes the end wall of the shock tube, it is reflected toward the driver side. At this point, the gas through which the reflected shock is traveling has already been heated and compressed. Due to the passage of the reflected shock, the driven gas is once again heated and compressed, this time to a greater extreme3. At higher Mach numbers associated with the shock front speed, temperature differences can be from 500 to 5000 K, and pressure differences can vary from sub atmospheric to 500 atmospheric pressures4. This versatility of temperature and pressure ranges allows a broad range of applications to be studied with shock tubes, including physics (e.g., equations of state), fluid dynamics, and chemistry.

A French scientist Paul Vielle performed the first experiment with a shock tube in 1899. He tested different types of diaphragm materials and several driver gasses5. Fomin reviewed 110 years of experimental techniques used in shock tubes throughout the world including high-speed optical diagnostics of shock wave processes5. A British scientist Walter Payman made important contributions to modeling and describing the detonation process in a shock tube and the shockwave propagation6. He performed experiments to verify the governing equation for the motion of shock waves by driving shocks with compressed air rupturing a copper diaphragm7.

Post-Second World War shock tube development gained lot of momentum due to interest from several disciplines. For chemists, the motivation was a better understanding of reactions in high-temperature gases3. Gaydon and Hurle also showed a practicing research worker how to go about producing and studying shock waves in their laboratory3. Walker Bleakney constructed the first shock tube at Princeton in 19498. Bleakney’s work is particularly relevant in the context of the current study because his team compared laboratory measurements with blast damage to several buildings tested at Edgewood arsenal. Tests were conducted with full scale bombs and small-charge blasts9.

During the Cold War era a large amount of research was conducted on various aspects of supersonic aerodynamics using shock tubes10. The co-discovery of Richtmyer-Meshkov instability (RMI)11,12 led to studies of shock-driven mixing and transition to turbulence, both because of the practical importance of the phenomenon and because it presents a well-defined yet challenging validation problem for numerical codes. These studies are still ongoing, in part, because RMI is important for inertial confinement fusion (ICF), where mixing degrades the performance of the fusion target13, and because of the role RMI and related Rayleigh–Taylor instability play in astrophysics14.

In recent years there were several noteworthy advancements in shock tube experiments and in related simulations. One of the limitations of the shock tube is the transient nature of the flow, with sustained post-shock conditions usually not extending beyond several milliseconds. However, for problems where this presents a disadvantage, this time which can be extended by increasing the driver section length and varying the driver gas. This makes it possible to extend the test times to as long as 35 ms4. Similar techniques were used to study shock propagation through mixtures of gases with disparate properties (SF6 and helium), leading to a surprising result that neither Dalton’s nor Amagat’s classical mixing laws describe the state of such mixtures accurately15, requiring kinetic molecular theory (KMT) analysis considerations to explain the observations. Detailed experimental observations, such as a study of shock interaction with an inclined cylindrical density interface16, are used to validate advanced numerical codes that reproduce both the flow morphology and turbulent statistics observed in experiment17. The inclined cylinder study16 used the same facility as the present work for generation of shocks.

Among other notable advancements are diagnostic methods, specifically high-speed flow visualization using line-of-sight18 and laser-sheet16 techniques. The most recent development in this area is holographic imaging19. Some earlier experiments used small particles or droplets as tracers, with analysis of their flow-tracking fidelity showing that they are suitable for low Mach number experiments20. However, the presence of particles and droplets can change the physics of the flow, especially at higher Mach numbers, leading to formation of shock-driven multiphase instability (SDMI)21.

One drawback of the conventional shock tube experiment is the single shot nature of the facility. This drawback can be mitigated by using diaphragm-less shock tubes22.

One more area where shock tubes have been used is shock interaction with objects, such as spheres lying on the surface of the driven section of the shock tube23. The goal of this study was to assess the drag coefficient of a sphere in highly non-stationary shocked flow. The role of surface roughness in shock-driven particle advection off a surface was also studied in the facility used in the present investigation24. However, many such studies (with at least one exception cited above) do not attempt to bridge the gap between small-scale laboratory experiments and real-world blasts (weapons of war, industrial accidents, meteorite strikes). Our motivation is to develop an experimental setup and diagnostic techniques that would make it possible to create a well-characterized test governed by the same physics as a real event. For example, during the Operation Upshot-Knothole nuclear test25, a nuclear explosion produced a blast wave that hit a planted grove of ponderosa trees, with pressure measurements and high-speed cinematographic recordings acquired. An additional incentive for the current work would be the ability to apply the same diagnostic techniques (pressure traces, visualization) to laboratory experiments and archival footage, with the ultimate practical goal to develop reduced-order physics-based models that describe both the small-scale and the large-scale phenomena.

Experimental setup

Shock tube and pressure sensors

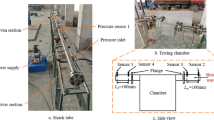

Figure 2 shows the schematic of the experimental setup where the interaction of the shockwave with solid objects was studied. The modular shock tube at UNM Fluid Mechanics lab is comprised of a driver section, a driven section, an optically transparent test section, and a run-off section. The shock tube is mounted on a long table in a manner that allows for variation in both the height of the shock tube from the floor and its angle with respect to horizontal.

For this study it stayed horizonal throughout all the tests we ran. The whole setup has a vibration isolation mechanism to reduce noises from external vibration by placing rubber dampers between the support structure and facility floors. To calculate the key parameters of each experiment, several values must be known: the initial driver and driven gas pressures and temperatures, the properties of the driven and driver gases, and the velocity of the incident shock wave. The initial gas pressure is measured by the simple use of pressure transducers prior to the bursting of the diaphragm. The properties of the driven and driver gases can be readily calculated by assuming ideal-gas mixtures. Measuring the velocity of the incident shock wave presents a larger challenge. In modern experiments, this is typically done by placing high-speed (10–100 MHz bandwidth) pressure transducers along the length of the driven section and monitoring the pressure spike at each transducer as a surrogate for the time when the incident shock wave passes. If the difference in time of passage for each transducer is known and the distance between each transducer is known, then the average velocity of the wave between two transducers can be calculated. Since the shock wave attenuates over the length of the tube, the velocity measurements are usually made at several different locations to estimate the attenuation, which is typically quite linear. The velocity of the incident shock can then be extrapolated out to the correct distance from the last measurement so that the true velocity at the end wall can be entered into the computer code. For this study four transducers were used–two upstream and two downstream of the test samples.

Development of a sample holder

A sample holder shown in Fig. 3 was designed carefully to facilitate shock wave interaction with the sample objects placed in the test section. It can hold at a maximum of three rows of solid objects, five per row (one could think of this arrangement as an idealized small-scale version of the ponderosa pine grove in the Operation Upshot-Knothole tests). The distance between the rows is 0.2 inch and within each row the distance between the centers of two adjacent objects are 1/2 inch. For this study shock waves with Mach numbers of 1.2, 1.5 and 1.7 were tested on 1, 2 and 3 rows of aspen wood match sticks placed on this sample holder which was installed inside the test section of the shock tube.

Dual imaging and test section upgrade

A flat mirror was set up on top of the test section at angle of 45 degrees. This makes it possible to capture two views of solid samples interaction with shock waves—in the horizonal plane (from above) and in the vertical plane (head-on) using the same camera at the same time as shown in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4, an earlier configuration of top panel of the test section is shown, with an opening for injection of a falling particle curtain. This opening was removed (Fig. 5).

The transparent parts of the test section were built using thick (1/2 inch) UV resistant acrylic sheet. Polycarbonate was also considered, but preference was given to acrylic to improve visibility.

Experimental conditions

For the initial experiments, matchsticks (aspen wood, 2 mm by 2 mm by 43 mm) were picked as the solid object to be mounted on the sample holder. Table 1 lists the experimental conditions that will be presented in this study. Nitrogen gas was used to pressurize the driver section. The driven section was kept at atmospheric pressure (monitored at average 13.2 psi—Albuquerque, where the experiments were conducted, is at considerable elevation above sea level). Moisture resistant polyester films of three different thicknesses were used to generate three different Mach numbers as shown in the same table. This Polyester film has a smooth texture which is helpful to make a good seal when placed between the driver and driven sections of the shock tube. It has a high tensile strength, for example, the 0.010-inch-thick diaphragm has 28,000 psi tensile strength. As the N2 gas filled the driver section, pressure increases, and the diaphragm deforms and strain-hardens. Selection of the correct thickness is important as lower thickness diaphragm can cause premature burst of shock wave with lower Mach number. As the value of the pressure required to produce the desired Mach number is reached, the diaphragm is ruptured by a pneumatically driven hunting arrowhead (broadhead) with four cutting edges, resulting in a clean x-shaped cut opening the diaphragm and releasing the shock.

A set of initial tests was run to collect baseline pressure traces, i.e. pressure traces with the shock passing through the test section without interaction with any solid objects. Baseline tests used the same Mach numbers (1.3, 1.5, 1.7) as the experiments with samples, but with the empty sample holder. Tests for each Mach number were run five times to take an average of the base condition without any sample/obstruction in the test section.

Experimental results and discussion

Comparison of pressure traces

Pressure traces shown in Figs. 6 and 7 correspond to three different configurations acquired with and without the opening at the end of the test section, as described in the previous section. In the case of the open-ended configuration, the shock exits into a baffle box (Fig. 2) designed to suppress the reflected shock, with the difference between the configurations apparent in the traces. The pressure traces appeared more sensitive to the configuration of the sample when the tests ran with the closed test section. The reason for this higher sensitivity is that the expansion wave remains confined within the shock tube. These fluctuations (absent in the test runs without the solid objects) are weaker at Mach number 1.3. It can be concluded that the closed test section has improved the pressure readings to be more consistent and responsive.

For pressure traces at Mach 1.7 with the closed test section the scale of the sensors needed to be adjusted from 1 to 5 V because of the increased transducer signal magnitude as shown in Fig. 8.

Mach number verification

The pressure in the driver section required to generate a specific Mach number can be calculated using shock-tube theory8. An online tool developed by Professor Riccardo Bonazza26 simplifies the calculations. However, the actual Mach number produced by a given driver-section pressure may vary due to imperfect diaphragm rupture, as well as flow obstruction by the puncture. Accordingly, we compared pressure traces from Channel 1 and Channel 3 transducers located upstream of the test section. From the arrival times of the shock wave at each of these transducers, velocity of the shock wave was calculated by dividing the distance between those two transducers by the time difference in the arrival of the shock wave. Then Mach number was calculated by comparing the shock wave velocity with the velocity of sound in the lab. Figure 9 shows pressure traces used for Mach number verification for Mach number 1.5. It was verified similarly for Mach number 1.3 and 1.7. Table 2 shows the difference between the theoretical value and the measured Mach number for the tests in this study, where error is less than 5%. Moreover, the results are highly repeatable. This close comparison between theoretical and experimental Mach numbers ensures not only structural integrity of the shock tubes but also validity of the measurement systems which is critical for the experiments ran using them. Mach 1.7 shows 0 standard deviation because the measuring range was increased to 10 V in compare to 5 V for the other Mach number tests to capture the complete pressure traces. This drove the fluctuations in the Mach number below the recording system sensitivity threshold.

Analysis of pressure traces post interaction

Two sensors were located at the top and bottom plane of the test section at the same distance from the test objects. Out of 600 data points measured, 300 were extracted to focus on the interest zone. In a broader sense there is no notable difference among the reading from top and bottom pressure sensors ran under same Mach number even with different orientations of the matchsticks, as shown in Fig. 10. Higher Mach number shock waves reached the transducers faster, and their peak pressure spikes were also higher than at lower Mach numbers.

Figures 11 and 12 show the comparison of signals recorded by the downstream bottom pressure sensor with the baseline pressure traces. As anticipated, pressure traces showed higher fluctuations post interaction with the solid objects vs. the baseline pressure. Small fluctuations in the latter are likely due to small imperfections in the shock tube such as seams between the sections, as well as transducer mounting holes. In the Mach 1.7 tests, the fluctuations for 3 rows of matchsticks were higher compared to the other two configurations, as there were more physical objects to exchange momentum with. Moreover, the incident shock reflected off the matchsticks, causing higher pressure readings. Note that the blockage ratio of the matchsticks was quite modest (6% of the test section cross-section). The result, however, is not surprising, given that even a diffuse solid particle cloud was observed to reflect incident shocks27.

x-t diagram of the baseline tests

As mentioned previously, tests were run without any samples and x-t plots shown in Fig. 13 are a graphical representation of the wave velocity at different sections of the shock tube for that case. Red lines indicate the position of the diaphragm and interaction with the test sample. Blue lines indicate reflected waves whereas dashed lines indicate location of the imaging windows. Shock tube dimensions along with the information about the driver, driven, and test gas information were given in an input file which was then used in a MATLAB code to generate these plots. Time increment between the output files delta t was calculated using the formula:

Here, Ldriver is the length of the shock tube including test section and run off section (5.9457 m) and Ldiaph is the location of the diaphragm (1.245 m) separating driver and driven section of the shock tube. Location of the interaction from the end of driver section is 4.6494 m. The plots show very close agreement with the experimental pressure vs time plots in Figs. 6, 7a. The shock wave velocities were also calculated at the intersection, about 430 m/s, 514 m/s and 587 m/s respectively for nominal 1.3, 1.5 and 1.7 Mach numbers. Note that the shock velocities in experiment are consistently lower by a modest amount, as are the Mach numbers.

Velocity of the solid objects

A Chronos 2.1 high-speed camera28 was used to capture images of the shock-sample interaction at 4,325 frames per second and 800 × 600 pixel resolution. Phantom 6410 high speed camera of frame rate 65,000 and resolution 1280 × 800 was used for the tests ran under 1.7 Mach number. Two views (in the following figures, top: from above, bottom—from the side) were captured simultaneously. While this arrangement is less sophisticated than the holographic imaging system19, it still provides enough information to track the shock-produced debris in our setup.

Videos capturing the moment of interaction between shock waves and the matchsticks were used to extract 300 frames from the moment of shockwave striking the objects by using ffmpeg software29. Five frames from the moment of impact of the wave to the match sticks were selected. For 1.7 Mach number tests 500 frames were captured form the moment of interaction and 75 frames from the moment of interaction were selected. These extracted frames were then stacked together using ImageJ software30. Using the superimposed frames in ImageJ, object (matchstick) displacement together with the known resolution per pixel was used to calculate the matchstick velocities. The velocity was calculated using the following formula:

With dual-plane imaging, as shown in Fig. 14, it was possible to measure the velocity of the maximally deflected extremity of each object in two planes (vertical x–z and horizontal x–y, with x-axis in the downstream direction) and calculate its full velocity using V = \(\sqrt{{v}_{x}^{2}+{v}_{y}^{2}}\). Velocities were measured at least 3 times for each condition and Fig. 15 shows the velocity trends of matchsticks for each configuration listed in Table 1. No attempt was made to achieve subpixel resolution, which puts the limit on the accuracy of our individual velocity reconstruction. The center matchstick of the center row was used each time for the velocity calculation. It appears that the velocities of the matchsticks were attenuated about 30% with the addition of a second row in front of the center row. This front row of match sticks took the first impact from the shock wave arriving and thereby reduced the impact to the row of match sticks behind. But it didn’t show a significant reduction with an addition of another row of matchsticks behind the center row. A declassified video of a comparable nuclear test (Operation Upshot-Knothole) is available on Youtube, and it shows a remarkably similar behavior of trees hit by a nuclear blast wave31.

Overall, the velocities of the objects are much smaller than the gas velocities behind the shock front (hundreds of meters per second). In this case pressure increases slightly after the interaction due to addition of reflected waves. Of course, this velocity mismatch is mostly due to the much higher density of the objects and the fact that they initially occupy only about 6% of the cross-section of the shock tube. In our earlier work21, we described a multiphase analog of Atwood number characterizing Richtmyer–Meshkov instability, A = (ρ1–ρ2)/(ρ1 + ρ2). For classical single-phase instabilities, ρ1 and ρ2 are the densities of the heavy and light gas respectively. For multiphase flows, ρ1 is the average density of the volume enclosing particles (or, in our case, matchsticks—simulated debris), while ρ2 is the density of the debris-free gas. Since ρ1 > > ρ2, the multiphase Atwood number is close to its limit value of unity. Moreover, the other parameter describing the flow, the representative time it takes for the non-gaseous phase to catch up with the shock-accelerated gas, here approaches infinity.

Conclusion

Shock tube studies have a long history and many motivations that drove research over time. Practical interest in blast waves and their effects on structures remains such a motivation since at least the time of World War II, however, the state of the art could benefit from developing a better understanding of the relationship between small-scale laboratory experiments and large-scale events. The present work can be considered as a necessary step in a program of studies to develop such an understanding. Presently we can report the following initial results.

-

1.

An experimental setup for testing the interaction of solid objects with shock waves at precisely controlled Mach numbers has been developed.

-

2.

Preliminary testing using matchsticks with three representative configurations at three different Mach numbers was performed. Each test was repeated three times for repeatability, showing consistent results.

-

3.

Pressure traces of the shock waves after passing through the rows of matchsticks were highly repeatable and more sensitive to the presence of the matchsticks in a closed shock tube configuration (runoff section terminated with a wall rather than open into a baffle box).

-

4.

Pressure traces detected at the top and bottom sensors downstream of the interaction were compared to reveal only a modest variation of pressure between the top and the bottom transducer, despite the matchsticks initially protruding into the test section (76 mm height) for about 40 mm from below.

-

5.

Pressure traces in the presence of matchsticks were compared with baseline pressure traces, revealing higher pressure fluctuations, increasing both with Mach number and with more objects in the path of the shock wave.

-

6.

The velocity of the objects due to the interaction with shock wave was calculated and it showed considerable sensitivity to the initial placement of the objects.

-

7.

The object velocity at all Mach numbers tested was very small compared to the bulk gas velocities

Future studies will include testing of the material properties of matchsticks (force it takes to remove a matchstick from its holder, force it takes to break a matchstick), quantification of how many matchsticks were dislodged or broken at different configurations and Mach numbers, and eventually a transition to tests with different objects, such as 3D-printed cylinders with different cross-sections and heights. The goal of these tests is to provide validation data for numerical modeling of shock-solid object interaction, as well as to develop insights that could lead to formulation of reduced-order models to describe the propagation of a shock-driven debris cloud. The image-based diagnostics developed to analyze the experiments described here will also be applied to archival footage of nuclear tests and to recent recordings of blasts producing damage, such as the Chelyabinsk asteroid explosion32.

Details of the interaction between the shock and a deformable/breakable structure must be elucidated by a numerical study revealing the pressure and velocity fields in the gas (on the hydrodynamic side) and the stress and deformation field on the solid-mechanics side. Practical modeling of a large-scale blast in an urban environment with this level of detail may still be prohibitively expensive computationally. Even for a simpler validation problem (blast accelerating a cylindrical gas column), there are multiple instabilities manifesting on several scales to produce a complicated flow field with transition to statistically non-Kolmogorov turbulence17. Accordingly one of the goals for our future work is to develop reduced-order models characterizing the blast-object interaction in terms of basic conservation considerations and remaining faithful to the experiment. In the present study, the diagnostic we describe will be useful to determine what fraction of the momentum and energy of the blast is transferred to the debris cloud the interaction produces.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Planning guidance for response to a nuclear detonation, second edition, June 2010, National security staff of interagency policy coordination sub-committee.

Glasstone, S. and Dolan, P. J. The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Online edition U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C., (2022).

Gaydon, A. G. & Hurle, I. R. The Shock Tube in High-Temperature Chemical Physics (Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963).

Davidson, D. Recent advances in shock tube/laser diagnostic methods for improved chemical kinetics measurements. Shock Waves 19(4), 271–283 (2009).

Fomin, N. A. 110 years of experiments on shock tubes. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 83(6), 1118–1135 (2010).

Payman, W. Explosion waves and shock waves Part II The shock wave and explosion products sent out by blasting detonators. Proc. of the Royal Soc. London Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 148(865), 604-622.11 (1935).

Payman, W. Explosion waves and shock waves. Part VI. The disturbance produced by bursting diaphragms with compressed air. Proc. Royal Soc. London Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 186(1006), 293–321 (1946).

Bleakney, W. The shock tube: A facility for investigations in fluid dynamics. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 20(11), 807–815 (1949).

Bleakney, W. National Academy of Sciences 1998 Biographical memoirs: V73 Washington DC The national Academic press https://doi.org/10.17226/9650.

Glass, I. I. and G. Hall, Handbook of Supersonic Aerodynamics, Section 18, Shock tubes. Vol. 6. 1958, Silver Spring, MD.

Richtmyer, R. D., Taylor Instability in Shock Acceleration of Compressible Fluids (No. LA-1914). Los Alamos Scientific Lab, (1954).

Meshkov, E. E. Instability of the interface of two gases accelerated by a shock wave. Fluid Dyn. 4(5), 101–104 (1969).

Youngs, D. L. Numerical simulation of mixing by Rayleigh-Taylor and Richtmyer–Meshkov instabilities. Laser Part. Beams 12(4), 725–750 (1994).

Kane, J., Drake, R. P. & Remington, B. A. An evaluation of the Richtmyer–Meshkov instability in supernova remnant formation. Astrophys J. 511(1), 335 (1999).

Wayne, P. et al. Dalton’s and Amagat’s laws fail in gas mixtures with shock propagation. Sci. Adv. 5(12), p.eaax4749 (2019).

Olmstead, D. et al. Experimental study of shock-accelerated inclined heavy gas cylinder. Exp. Fluids 58, 1–20 (2017).

Romero, B. E., Reisner, J. M., Vorobieff, P. & Poroseva, S. V. Statistical characterization of a shock interacting with an inclined gas column. J. Fluid Mech. 971, A26 (2023).

Brouillette, M. and Bonazza, R., Experiments on the Richtmyer–Meshkov instability: Wall effects and wave phenomena (1999).

Mansoor, M. M. & George, J. Investigation of the Richtmyer–Meshkov instability using digital holography in the context of catastrophic aerobreakup. Exp. Fluids 64(2), 40 (2023).

Rightley, P. M., Vorobieff, P. & Benjamin, R. F. Evolution of a shock-accelerated thin fluid layer. Phys. Fluids 9(6), 1770–1782 (1997).

Vorobieff, P. et al. Vortex formation in a shock-accelerated gas induced by particle seeding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106(18), 184503 (2011).

Tranter, R. S., Giri, B.R. A diaphragm less shock tube for high temperature kinetic studies, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79 (2008).

Igra, O. & Takayama, K. Shock tube study of the drag coefficient of a sphere in a non-stationary flow. Pro. Royal Soc. London. Series A Math. Phys. Sci. 442(1915), 231–247 (1993).

Wayne, P. J. et al. Shock-driven particle transport off smooth and rough surfaces. J. Fluids Eng. 135(6), 061302 (2013).

Greer Jr, W. R., Dukes, E. F. and Defense atomic support agency Washington DC, 1954. Operation UPSHOT-KNOTHOLE, Nevada Proving Grounds, March-June 1953. Project 9.1, Technical Photography, (1954).

Bonazza, R., WiSTL Gas Dynamics Calculator, https://silver.neep.wisc.edu/~shock/tools/gdcalc.html, accessed Sep. 25, 2024, (2024).

Izard, R. G., Reddy Lingampally, S., Wayne, P., Jacobs, G. & Vorobieff, P. Instabilities in a shock interaction with a perturbed curtain of particles. Multiphase Flow: Theory Appl. 6(1), 59–70 (2018).

Kron Technologies, Chronos 2.1-HD High Speed Camera, https://www.krontech.ca/product/chronos-2-1-hd-high-speed-camera/, accessed Sep. 25, 2024, (2024).

FFmpeg, FFmpeg—a complete, cross-platform solution to record, convert and stream audio and video, ffmpeg.org, accessed Sep. 25, 2024, (2024).

ImageJ, ImageJ - image processing and analysis in Java, https://imagej.net/ij/, accessed Sep. 25, 2024 (2024).

Youtube, Nuclear Weapon Effects on Trees, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0kxCjiIyBA , accessed Sep. 25, 2024 (2024).

Kring, D. A. & Boslough, M. Chelyabinsk: Portrait of an asteroid airburst. Phys. Today 67(9), 32–37 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the US Department of Energy grant DE-NA0004108, "The Rio Grande Consortium for Advanced Research on Exascale Simulation (Rio Grande CARES)."

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.—Designed the experimental setup and parameters to run all the tests, analyzed all the data. Also wrote the whole manuscript. A.M.—Helped to run the experiments specially with Kronos camera A.S.—Helped to run experiments when we got Phantom camera J.C.—helped to develop dual plane imaging which was used for his experiments too. P.V.—Professor of Mechanical Engineering department, My supervisor and PI to this project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, M.S., Mohamed, A., Sweis, A. et al. Development of a novel method to characterize shock waves interaction with solid objects. Sci Rep 14, 28956 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79220-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79220-6