Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common monogenic disorder in Saudi Arabia, which associates with an increased risk of organs damage, including the kidney. The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence and predictors of sickle cell nephropathy (SCN) in the Saudi population. A retrospective study was conducted from April to October 2023, and included 343 adult patients with SCD who were recruited from the hereditary blood diseases center (HBDC), Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Spot protein-to-creatinine ratio was measured and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated from serum creatinine using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. As per KIDGO guidelines, CKD was diagnosed in 93 (27.1%) patients. Based on the CKD-EPI equation, 2% of patients had low GFR (eGFR < 60mL/min), 28.3% had high GFR (eGFR > 140 mL/min), and 69.7% had normal GFR. Among SCD patients, proteinuria was observed in 26.5% of the patients. SCD patients with CKD were significantly older than non-CKD patients (p < 0.001) and had higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HTN) (p = 0.045 and 0.001 respectively). The multivariate analysis showed that age (P = 0.001; OR 1.035; 95% CI 1.014–1.056) and low hemoglobin level (p = 0.034; OR -0.851; 95% CI 0.721–0.980) were independent risk factors for the development of SCN. Nephropathy is a common complication among patients with SCD as early as the third decade of life, although they remain asymptomatic. Advances in age and low hemoglobin levels are the main predictors of nephropathy. In addition, SCD patients with coexistent comorbidities, particularly DM and HTN, were at increased risk of developing kidney disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common monogenic disorder in Saudi Arabia that results from a mutation in the β-globin gene, causes red blood cell sickling, vaso-occlusion, and hemolysis1. SCD affects millions of people worldwide and is particularly common among people whose ancestors came from sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, approximately 72,000 Americans are affected by SCD, and 2 million are carriers of the condition. In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of sickle-cell trait ranges from 2 to 27%, and approximately 2.6% of the population is affected2. However, the prevalence of SCD varies greatly across Saudi Arabia, with the eastern province having the greatest frequency followed by the southern provinces. Furthermore, the variability extended to genotypes and clinical presentations2,3.

The hallmark of SCD is pain, but it is also associated with numerous acute and long-term complications. Repeated episodes of vaso-occulsive crisis, infarction, and chronic hemolytic anemia may lead to end organ damage, including the kidney4. Effective renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rates (GFR) are higher in younger patients with SCD. These values fall to normal ranges in young adulthood and subnormal levels as age advances. Compared with people with sickle cell trait or healthy individuals, those with SCD are exposed to rapid loss of kidney function5.

The complete pathophysiology of sickle cell nephropathy (SCN) is not fully understood. However, the unique physiologic conditions of the kidney make it more susceptible to kidney damage in SCD. In patients with SCD, the acidic and hypoxic conditions of the renal medulla make it more likely that red blood cells (RBCs) will sickle, which can cause vaso-occlusion, microinfarction, and ischemia. This ischemia alteration releases prostaglandins and nitric oxide, which increases renal blood flow and hyperfiltration6,7,8. Therefore, nephropathy is a serious consequence of SCD, which can progress to overt kidney failure that first manifests in childhood. Furthermore, chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with SCD is associated with an increased risk of mortality during the early stages of their clinical condition9.

To the best of our knowledge, only a limited number of studies have addressed the prevalence of kidney involvement among Saudi patients with SCD. Therefore, this study aimed to define the prevalence and predictors of SCN among adult patients with sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

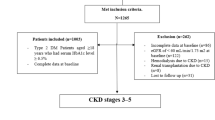

A retrospective analysis was conducted from April to October 2023, and included 343 adult patients with SCD, who were recruited from the hereditary blood diseases center (HBDC), Alahsa, Saudi Arabia. The HBDC is a main center for patient with sickle cell disease in Eastern province, which has the greatest prevalence of SCD in Saudi Arabia. Patients with preexisting kidney disease, Patients with sickle cell traits and those who had an acute illness were excluded from the study.

The following information was obtained from the patient’s medical record system: sociodemographic data (age, gender, body mass index, and smoking), basic clinical (comorbidities, and previous surgeries), laboratory data (complete blood count, hemoglobin electrophoresis, liver function tests, and kidney function tests), and medication history. Serum creatinine and spot protein to creatinine ratio were measured to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and diagnose patients with CKD. eGFR was determined using 2021 chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation10.

CKD was diagnosed and classified according to 2012 KDIGO criteria. CKD patients were diagnosed if they had evidence of kidney damage (e.g. urinary protein excretion ≥ 150 mg/day or equivalent) or eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for ≥ 3 months, irrespective of the cause11.

Statistical analysis

A statistical package for social science (SPSS) application for Windows version 22 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyze the data. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation were used, whereas percentages and numbers were employed to represent categorical data. Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test (X2) were utilized to compare the two sets of categorical data. When suitable, the independent t-test and Mann –Whitney U test were employed to compare the two sets of quantitative data. To estimate the risk factors for chronic kidney disease in patients with SCD, logistic regression assessment was employed. A significance level of P < 0.05, two-sided hypothesis tests were used as the foundation for all statistical studies.

Ethical considerations

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Fahad Hospital (IRB KFHH No. (H-05-HS-065)). To preserve data integrity and patient privacy, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were gathered, coded, and analyzed.

Results

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics

A total of 343 patients with SCD were recruited in this study, of which 171 were females (49.9%) and 172 were males (50.1%). The mean age of the patients was 33.15 years, and their ages ranged from 17 to 85 years. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension represent 6.4% and 5.2% of SCD patients, respectively. Among SCD patients, 9% were underweight, 49.3% had average body weight, 26.8% were overweight, and 14.9% were obese. (Table 1).

Regarding previous surgeries, 122 (35.6%) patients underwent cholecystectomy, 59 (17.2%) underwent splenectomy, and 19 (5.5%) had hip replacement. Regarding medications, hydroxyurea was taken by 50.1% of patients, whereas the following analgesics were used: paracetamol 71.4%, ibuprofen 43.1%, tramadol 14.3%, and morphine 6.7%. (Table 1).

The laboratory results showed that the mean values of hemoglobin, Leukocytes, and platelets were 9.98 g/dL, 8.36 × 103/mm3, and 329.58 × 103/mm3, respectively. The hemoglobin electrophoresis results showed that the means of hemoglobin S, hemoglobin F, hemoglobin A2, and hemoglobin A were 79.69%, 15.27%, 3.42% and 1.18%, respectively. Based on eGFR, using the CKD-EPI equation, 2% of patients had low GFR (eGFR < 60mL/min), 28.3% had high GFR (eGFR > 140 mL/min), and 69.7% had normal GFR. Proteinuria was observed in 26.5%. According to the KIDGO guidelines, CKD was diagnosed in 93 (27.1%) patients with SCD (Table 1).

BMI Body Mass Index, HBA Hemoglobin A, HBA2 hemoglobin A2, HBS Hemoglobin S, HBF Hemoglobin F, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase, ALT Alanine Transaminase, ALP Alkaline Phosphatase, LDH Lactate Dehydrogenase, eGFR Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, N Number, SD standard Deviation.

Characteristics of SCD patients with chronic kidney disease

Baseline characteristics stratified by CKD status are shown in Table 2. Patients with CKD were significantly older than those without CKD (p < 0.001) with a mean age of 37.78 years. DM and HTN were more prevalent in CKD patients than in non-CKD ones (p = 0.045 & 0.001 respectively). In addition, CKD patients had significantly higher levels of Leukocytes, hemoglobin A, ALT, AST, and ALP (p = 0.031, 0.032, 0.005, 0.001 & 0.031 respectively), but significantly lower levels of hemoglobin (p = 0.001). SCD patients with CKD had undergone cholecystectomy more often than non-CKD patients (p = 0.006) (Table 2).

CKD chronic Kidney Disease, N number, BMI Body Mass Index, HBA Hemoglobin A, HBA2 hemoglobin A2, HBS Hemoglobin S; HBF, Hemoglobin F, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALT Alanine Transaminase, ALP Alkaline Phosphatase, LDH Lactate Dehydrogenase, eGFR Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate.

*significant at p-value ≤ 0.05.

Risk factors for chronic kidney disease in SCD patients

Table 3 shows the factors associated with the risk of developing CKD among patients with SCD.

BMI Body Mass Index, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase, LDH Lactate Dehydrogenase.

Discussion

The kidney is a vital organ that plays a central role in metabolic waste elimination, erythropoiesis, blood pressure regulation, electrolyte balance, blood pH, and mineral homeostasis. It is an energy-demanding organ and is constantly exposed to endogenous and exogenous insults, leading to the development of acute kidney injury (AKI) and subsequently CKD12,13. AKI and CKD are common public health problems that are increasingly recognized as leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally14,15. Several systemic diseases affect the kidney, although diabetes mellitus is considered the driving cause and accounts for 50% of cases worldwide16,17.

Hemolysis and vaso-occlusion are the main pathogenic phenomena of SCD, leading to endothelial dysfunction and vasculopathy, ischemia/reperfusion damage, oxidative stress, hypercoagulability, nitric oxide deficiency (free Hb resulting from intravascular hemolysis binds to nitric oxide and sequesters it), platelet activation, and increased neutrophil adhesiveness. All of this causes acute and chronic manifestations that can affect any organ and could explain the development of SCN18.

SCN is a serious complication of sickle cell anemia with asymptomatic onset and is closely linked to mortality, particularly in those who survive 60 years of age or more19,20,21. SCN is also found in up 12% of adult patients with a mean age of onset 37 years22,23. Interestingly, the prevalence of nephropathy in our study was two-fold (26.5%) higher than that previously reported and with comparable mean age at the time of diagnosis22,23.

Glomerular hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria/proteinuria are early manifestations of sickle cell nephropathy24. Similarly, the majority of nephropathy in the present study was in the form of proteinuria in the presence of a normal glomerular filtrate rate, which was similar to previous studies22,25. This was previously attributed to increased GFR, decreased muscle mass, and increased tubular creatinine secretion among patients with SCD, which render microalbuminuria a sensitive diagnostic indicator of early glomerular injury26.

The median survival for patients with SCD has not changed substantially over the past 25 years. However, several factors have been found to be closely linked to reduced survival and increased mortality, including those associated with CKD. The onset of CKD is insidious and multifactorial. Therefore, early identification of patients who are at the highest risk of developing significant renal complications may prevent and slow the progression of CKD26,27. We found that individuals with coexistent mortality, particularly those with diabetes mellitus and hypertension, were at increased risk of developing kidney disease. In addition, lower hemoglobin levels and advanced age were found to be strong predictors of CKD. Our findings are similar to previous studies which showed that CKD is associated with lower hemoglobin levels, increased age28, , preexisting hematuria, proteinuria29, lower baseline hemoglobin, higher reticulocyte count, and higher LDH30.

Although participants with leukocytosis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and those with previous cholecystectomy were more likely to have CKD, none was significant enough to be used as a predictor. On the other hand, both hemoglobin F and hydroxyurea are well-known SCD severity modifiers that exert protective effects against nephropathy, although the results from our study population were inconclusive25,31.

This study highlights that nephropathy is a common complication among patients with SCD as early as the third decade of life, despite the asymptomatic nature. Furthermore, proteinuria in the presence of normal estimated GFR was the most common finding, rendering estimated GFR a poor indicator of SCN and a possible reason for late diagnosis. Our study was conducted in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, where the Arab and Indian haplotypes are predominant and the course of disease is expected to be less severe, although the prevalence was twofold higher. Similarly, despite the harmful effects of NSAIDs and the efficient protective role of hydroxyurea32,33, both were poorly linked to nephropathy in our study. These findings justify the multimodal approach among patients with SCD and open the door for future studies to explore other possible mechanisms of SCD nephropathy.

This study has several limitations, including the retrospective nature and the exclusion of the pediatric population. It is a single center experience, which may limit its generalizability to other regions of Saudi Arabia. In addition, the hydroxyurea dosage and whether patients were on the maximum tolerated dose of hydroxyurea could not be assessed in the present study. Although we identified kidney disease on the basis of laboratory findings (GFR, proteinuria) and clinical assessments, no kidney biopsies were performed to confirm the histological diagnosis of SCD nephropathy. Kidney biopsy might be helpful in future studies to sole cause of nephropathy. In addition, genetic factors may play a significant role in the development of kidney disease and should be considered in future research to better understand the pathophysiology of SCD nephropathy. Finally our findings were limited to the Saudi population and may not be generalizable to other countries with different population and ethnicity backgrounds.

Conclusion

SCN is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with SCD, although its diagnosis is probably overlooked because of a misleading normal eGFR and late screening. In addition, advances in age and low hemoglobin levels are the main predictors of nephropathy. The findings of this study warrant an early screening program for SCN and raising awareness of the modality and criteria of diagnosis. Furthermore, hydroxyurea is a fundamental treatment for patients with SCD; however, late initiation and suboptimal dosing are plausible reasons for nephropathy despite treatment. Finally, hemoglobin optimization, exploration of other nephropathy pathogenesis, and use of a multimodal approach are crucial to overcome SCD complexity and achieve better outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SCD:

-

Sickle cell disease

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney Disease

- SCN:

-

sickle cell nephropathy

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- CKD-EPI:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- HTN:

-

hypertension

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- SPSS:

-

statistical package for social science

- X2:

-

chi-square test

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

References

Yee, M. M. et al. Chronic kidney disease and albuminuria in children with sickle cell disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrology: CJASN. 6 (11), 2628 (2011).

Jastaniah, W. Epidemiology of sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 31 (3), 289–293 (2011).

Creary, M., Williamson, D. & Kulkarni, R. Sickle cell disease: current activities, public health implications, and future directions. J. Women’s Health. 16 (5), 575–582 (2007).

Wilson, M., Forsyth, P. & Whiteside, J. Haemoglobinopathy and sickle cell disease. Continuing Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain. 10 (1), 24–28 (2010).

Ataga, K. I., Saraf, S. L. & Derebail, V. K. The nephropathy of sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18(6), 361–377 (2022).

Kimaro, F. D., Jumanne, S., Sindato, E. M., Kayange, N. & Chami, N. Prevalence and factors associated with renal dysfunction among children with sickle cell disease attending the sickle cell disease clinic at a tertiary hospital in Northwestern Tanzania. PLoS One. 14(6), 1–13 (2019).

Naik, R. P. & Derebail, V. K. The spectrum of sickle hemoglobin- related nephropathy: from sickle cell disease to sickle trait. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2017:87–94 .

Halawani, H. M. et al. Prevalence of cerebral stroke among patients diagnosed with sickle cell disease at King Abdulaziz University Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Med. Sci. 24 (102), 464–471 (2020).

Powars, D. R., Chan, L. S., Hiti, A., Ramicone, E. & Johnson, C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine. 84 (6), 363–376 (2005).

Delgado, C. et al. A Unifying Approach for GFR Estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32 (12), 2994–3015 (2021).

Stevens, P. E., Levin, A. & Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 158 (11), 825–830 (2013).

Wei, K., Yin, Z. & Xie, Y. Roles of the Kidney in the Formation, Remodeling and Repair of boneVol. 29p. 349–357 (Springer New York LLC, 2016). Journal of Nephrology.

Kamt, S. F., Liu, J. & Yan, L. J. Renal-Protective Roles of Lipoic Acid in Kidney DiseaseVol. 15 (Nutrients. MDPI, 2023).

Hsu, R. K. & Hsu, C. yuan. The Role of Acute Kidney Injury in Chronic Kidney Disease. Vol. 36, Seminars in Nephrology. W.B. Saunders; pp. 283–92. (2016).

Peek, J. L. & Wilson, M. H. Cell and gene Therapy for Kidney DiseaseVol. 19p. 451–462 (Nature Reviews Nephrology. Nature Research, 2023).

Samsu, N. Diabetic Nephropathy: Challenges in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Vol. BioMed Research International. Hindawi Limited; 2021. (2021).

Hoogeveen, E. K. The Epidemiology of Diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Dialysis. 2 (3), 433–442 (2022).

Kato, G. J., Steinberg, M. H. & Gladwin, M. T. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of SCD. J. Clin. Invest. 127 (3), 750–760 (2017).

Elmariah, H. et al. Factors associated with survival in a contemporary adult sickle cell disease cohort. Am. J. Hematol. 89 (5), 530–535 (2014).

Thein, S. L. & Howard, J. How I treat the older adult with sickle cell disease. Blood. 132 (17), 1750–1760 (2018).

Derebail, V. K., Zhou, Q., Ciccone, E. J., Cai, J. & Ataga, K. I. Rapid decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate is common in adults with sickle cell disease and associated with increased mortality. Br. J. Haematol. 186 (6), 900–907 (2019).

Nnaji, U. M., Ogoke, C. C., Okafor, H. U. & Achigbu, K. I. Sickle Cell Nephropathy and Associated Factors among Asymptomatic Children with Sickle Cell Anaemia. International Journal of Pediatrics (United Kingdom). (2020).

Payán-Pernía, S. et al. Sickle cell nephropathy. Clinical manifestations and new mechanisms involved in kidney injury. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 41(4):373–382. (2021).

Hariri, E. et al. Sickle cell nephropathy: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 50 (6), 1075–1083 (2018).

Ataga, K. I., Saraf, S. L. & Derebail, V. K. The Nephropathy of Sickle cell Trait and Sickle cell DiseaseVol. 18p. 361–377 (Nature Reviews Nephrology. Nature Research, 2022).

Fitzhugh, C. D. Knowledge to date on secondary malignancy following hematopoietic cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2022 (1), 266–271 (2022).

Sharpe, C. C. & Thein, S. L. Sickle cell nephropathy - a practical approach. Br. J. Haematol. 155, 287–297 (2011).

Maurício, L., Ribeiro, S., Santos, L. & Miranda, D. B. Predictors associated with sickle cell nephropathy: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2021;67(2):313–317. (1992).

Stallworth, J. R., Tripathi, A. & Jerrell, J. M. Prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of renal conditions in pediatric sickle cell disease. South. Med. J. 104 (11), 752–756 (2011).

Xu, J. Z. et al. Factors related to the progression of Sickle Cell Disease Nephropathy. Blood. 128, 9–9 (2016).

Ataga, K. I. et al. Rapid Decline in Estimated Glomerular Filtration rate in Sickle cell anemia: Results of a Multicenter Pooled AnalysisVol. 106p. 1749–1753 (Ferrata Storti Foundation, 2021).

Nelson, D. A., Marks, E. S., Deuster, P. A., O’Connor, F. G. & Kurina, L. M. Association of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions with kidney disease among active young and middle-aged adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 2 (2), e187896. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7896 (2019).

Alsalman, M. et al. Hydroxyurea usage awareness among patients with sickle-cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Health Sci. Rep. 4 (4), e437. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.437 (2021).

Funding

This study was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project number KFU242366)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“KE and MoA”. Put conceptualization, wrote paper; “MuA and AA.” Participated in data analysis and reviewing; “NAA and NGA.” Participated in research design and in the writing; “EMA, EA and NEM”. Prepared final version of paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elzorkany, K., Alsalman, M., AlSahlawi, M. et al. Prevalence and predictors of Sickle Cell Nephropathy A single-center experience. Sci Rep 14, 28215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79345-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79345-8