Abstract

Two-dimensional materials are a class of atomically thin materials with assorted electronic and quantum properties. Accurate identification of layer thickness, especially for a single monolayer, is crucial for their characterization. This characterization process, however, is often time-consuming, requiring highly skilled researchers and expensive equipment like atomic force microscopy. This project aims to streamline the identification process by using machine learning to analyze optical images and quickly determine layer thickness. In this paper, we evaluate the performance of three machine learning models - SegNet, 1D U-Net, and 2D U-Net- in accurately identifying monolayers in microscopic images. Additionally, we explore labeling and image processing techniques to determine the most effective and accessible method for identifying layer thickness in this class of materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) van der Waals (vdW) materials are a class of materials that can be atomically thin, down to a thickness of \(\sim\)0.8 nm. These materials exhibit weak interlayer vdW interactions and strong intralayer covalent bonding. Due to their unique interlayer interaction, they provide access to a broader class of materials with tunable properties such as energy dispersion relations, bandgap control and carrier mobility1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. This tunability allows for greater design control over device properties, making them suitable for applications ranging from insulators in gate dielectrics to groundbreaking new electronics, such as superconductors for quantum computers1,4,9,10,11. These materials were first discovered in 2004 when graphene was fabricated using a piece of scotch tape to exfoliate an atoms-thick layer from graphite12,13. Today, large-scale manufacturing processes, such as vapor-phase epitaxy14,15,16and chemical vapor deposition17,18,19, are employed alongside the exfoliation method to grow these materials. Precisely controlling variables such as layer thickness during fabrication is challenging. As a result, characterization techniques are essential to properly identifying the grown material based on its physical and electrical properties.

Optical spectroscopy20,21, Raman spectroscopy3,7, photoluminescence10,22, hyperspectral imaging microscopy23, and atomic force microscopy8,24are some of the techniques used to determine the thickness of 2D flakes. However, these methods can be time-consuming and inefficient. In addition, the delicate nature of 2D materials25,26,27 requires complex set-up like a closed environment with inert gas, making certain characterization techniques expensive and not easy to operate. Among these methods, optical microscopy stands out as an easy and cost-effective method. It works by measuring the light path’s reflection at different intensities, depending on material absorption, with the light travelling an additional distance of material thickness when incident on the underlying substrate. The resulting interference between all the wavelengths of incident light can be calculated using contrast equation in Equation 1, where \(\hbox {R}_\text {mat}\) and \(\hbox {R}_\text {sub}\)denote the reflection spectra of the 2D flake and the substrate28, respectively.

The RGB values of each pixel are the averaged contrast spectra at the corresponding range of wavelengths. This allows a functional mapping that associates the thickness of a 2D sheet with its apparent color, like in the case of graphene28. However, the contrast spectra vary depending on illumination, substrate thicknesses, substrate type, and materials being studied, leading to a tedious process of determining the correct functional mapping for each sample. To address these issues, machine learning can be employed to find the accurate relationship between pixel color and layer thickness, streamlining the characterization of 2D materials.

Machine learning, a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), predicts the underlying patterns in a learning dataset and extracts features without manually defined functions. There are two main types of machine learning algorithms, supervised and unsupervised. Supervised learning algorithms learn to predict features in a sample using knowledge from labeled examples. They compare predictions to expected classification labels to continually refine the model28. Unsupervised learning algorithms, on the other hand, do not require labeled examples and refine the model by identifying groups with similar properties, such as pixel color. Previous researchers cite poor initial performances with unsupervised learning which requires human assistance29. Therefore, for the complex task of thickness identification of 2D materials, supervised machine learning is often preferred due to its higher accuracy and less manipulation of results30,31,32,33. However, it requires a dataset containing both the original optical images and the correct pre-classification of each pixel according to layer thickness. This is a significant challenge since optical images of 2D flakes do not automatically indicate layer locations- the core problem this paper aims to solve. Once a sufficient set of optical images is labeled, a trained machine learning model can automatically classify the layers.

While some authors have used deep learning to map optical images to other material characterization techniques23, the merits of combining optical microscopy with machine learning is the ability to abstract all the variable extraction to software rather than fancier equipment using preprocessing filters or computational methods. As reviewed by Mao et al.28, previous studies have successfully implemented machine learning algorithms for automatic layer characterization29,34,35and other material properties36,37,38such as mechanical strength39. In these studies, it is continually repeated the importance of a large dataset to train the model and obtain reasonable results. Due to the difficulty in procuring samples, a method called transfer learning is used where a smaller set of (labeled) images inputted to a pretrained neural network can lead to remarkably high accuracy23,28,29. It allows a decreased cost, the possibility of sharing datasets between institutions, and highly adaptable models. In our work, we systematically tested various approaches to find the best generalized solution for 2D material thickness characterization. Performance of three machine learning models-SegNet, 1D U-Net and 2D U-Net is compared in accurately identifying monolayers in microscopic images.

Methods

Given that machine learning is a fast and effective method for layer identification, we undertook a comprehensive approach to leverage its capabilities. We selected three machine learning models, acquired a dataset to train and test the models, and obtained labeled counterparts for the dataset. We then preprocessed the images, observed the results and metrics from the model prediction, and fine-tuned the models to identify the best-performing one.

We tested multiple machine learning models, with a focus on object segmentation models. Various image preprocessing methods and performance metrics were utilized, and visual results were used to validate and refine the methods that best supplemented the machine learning models. The algorithms were trained on laptop computers with eight 1.80 GHz processors or the Linux workstations in the ECE computer lab at University of Florida (UF).

Preprocessing

In segmentation problems, image preprocessing is an integral step to extracting only the important features to be identified such as contrasts, shapes, or dimensionality and filter out imperfections that could confuse the machine learning algorithm28,40,41. To better understand image segmentation, we attempted multiple preprocessing methods to quickly and easily identify layer thickness from optical images.

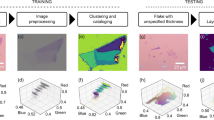

Due to its simplicity, we first analyzed the grayscale values across an image to pick out contrast variations across substrate and material. This was accomplished by placing a line across the image and measuring the pixel-by-pixel grayscale value - a direct measure of lightness. These values were recorded and plotted, providing a visualization that depicted the correlation between contrast variation and changes in layer composition. As illustrated in Fig. 1a–b, discernible shifts in lightness were observed as the line crossed from the substrate into the material. However, as the line crossed over the monolayer in the image, the results were not as consistent. The “grayscale” image preprocessing was only applied to the 1D and 2D Unet models.

Image Preprocessing Techniques. (a) The original image before any preprocessing. The blue line indicates where the contrast measurements were taken from. The scale is missing from the image source but should be \(\approx 100\,\mu m\) in width. (b) The contrast measurements along the blue line in the original image. The edges of the material are clearly demarcated by large jumps in contrast. (c) L*a*b* diagram with lightness information indicated by color and color information indicated by position: +a* for the red direction, -a* for the green direction, +b* for the yellow direction, and -b* for the blue direction. (d) RGB diagram with R and G for red and green color intensity and B for blue color represented by color of the data points. (e) Image preprocessing method total color difference (TCD) converted to various color spaces, from top to bottom: plasma, HSV and spectral color maps.

Lightness is not enough information to identify the layers of the optical images because contrast is also impacted by color - each wavelength of light illuminating the image contributes to the contrast40. The preferred color space in layer identification is L*a*b* space28,40. The L*a*b color space consists of three coordinates: L for lightness, representing color intensity from black to white; A, representing the difference from green to red; and B, representing the difference from blue to yellow42. Compared to RGB, the L*a*b* color space is more representative of what humans see and offers perceptually uniform color distinctions independent of the measuring device as demonstrated in Fig. 1c–d43. The L*a*b* representation of pixel color shows a wider spread, and the color of the data points showing Lightness overlap (as compared to Blue being restricted to specific Red and Green regions) meaning more unique information can be extracted from the L*a*b* space.

Using L*a*b*, we explored the technique of Total Color Difference (TCD). TCD quantifies the difference between two colors, measuring the color difference between material and substrate. In the TCD approach, the substrate is factored in by measuring the mean L*a*b values for the substrate and subtracting from each pixel’s L*a*b* value to derive a \(\Delta E\) value as shown in Eq. 240.

Once normalized based on substrate values, various color maps were applied to the extracted TCD value to encapsulate the contrast data into the easy-to-use (and visualize) image format. Three different color maps: plasma, Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV), and diverging or spectral color maps, were compared as shown in Fig. 1e. We found that for different conditions such as material type, substrate thickness, or flake shape, only some or none of the color maps could visually capture the topography of the optical images. This kind of image preprocessing akin to choosing an RGB channel or another manipulation of optical contrast requires steady experimental conditions28. However, a machine learning model doesn’t require all the variables to be known ahead of time because they are factored into the model more naturally through training. As such, the color maps called “TCD:Plasma”,“TCD:HSV”, and “TCD:Spectral” were applied to training images to compare which performed best as can be seen in the result tables of Section 5.

Lastly, a “normalized” preprocessing method was also applied to the training images. Not too different from the TCD method, it was adapted from44 and is detailed in Section 4 because of its utility in labeling.

As can be seen, the image processing methods we applied are not detailed enough to extract layer thickness for any dataset; this process still requires human supervision and must be adjusted for material type and how the samples were acquired28,40,41.

Labeling and data augmentation

As mentioned in the introduction, a dataset must initially be labeled through the tedious process of defining the boundaries of each class on a select group of training images. The labeling process is summarized in Fig. 2and facilitated by two unsupervised learning algorithms: SLIC and DBSCAN. After acquiring a labeled dataset, the number of labeled images can be multiplied by data augmentation. This reduces overfitting resulting from insufficient diversity in a dataset and improves the generalization of results to better align with real-world scenarios45. Most of the code for labeling and data augmentation was adapted and reworked from the \(Nanomaterial\_DeepLearning\)Github repository by Yafang Yang44, which was published in Ref.29. These methods will be described below.

Data source

We sourced our training data from the \(Nanomaterial\_DeepLearning\) Github which included 1400 optical microscopy images that were already resized and prelabeled for easy input into a learning model. The authors did not clarify the material used in each image, which could be one of 13 mechanically exfoliated 2D materials on either 285 or 90 nm \(SiO_2\)/Si substrates ranging from graphene, hBN, 2H-\(MoS_2\), 2H-\(WS_2\), 2H-\(WSe_2\), 2H-\(MoTe_2\), 2H-\(TaS_2\), 2H-\(NbSe_2\), 1T-\(HfSe_2\), BP, \(CrI_3\), \(RuCl_3\), and \(ZrTe_5\)29. However, the Github-available dataset was only a subset of this - the authors published a total of 3825 training images after data augmentation and data partitioning compared to the supplied 140029,44. Additionally, the authors provided 18 original OM images (compared to 817) to demonstrate the pre-labeling algorithm, which we could convert into a labeled dataset of 408 images as explained in Section 4.3. File \(Train\_example/images/bk\text{- }1w1235.jpg\)44 as shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 3, was used to demonstrate the entire preprocessing method due the obvious regions of different layer thicknesses. This image did not have a scale reference, but similar images were around 100 \(\mu m\) in width. Section 4details the human-assisted computational method used to establish the ground truth label map. The precedent for this is from Ref.29. While it may seem preparing our own samples would allow greater control of variables, this paper serves to illustrate the accessibility and robustness of supervised machine learning models for various materials and material preparations.

Labeling

Similar to Ref.29, this labeling process only uses the pixel color information in a human-assisted unsupervised learning method. No other characterization technique is used to confirm results.

As shown in Fig. 2, the initial step involves normalizing the images to mitigate variations between different experimental set-ups. This is achieved by converting the image into the L*a*b* color space as explained in Section 3, then adjusting it based on the image’s median with the following rules:

Rule 1. Divide lightness of specific pixel by \(\frac{L_\text {median}}{100} * 2\)

Rule 2. Subtract \(a_\text {median}\) and \(b_\text {median}\) from the specific pixel’s a and b values. Rule 3. Size image to one-tenth of it’s original size. The last step is so the pictures are processed faster. This normalized image preprocessing method is compared to the TCD method in Section 5.

Next, two unsupervised learning methods are adapted from Peter Koveski’s Image Segmentation Package. The first is called SLIC and adapts K-means clustering which can create many large “superpixels” (groups of pixels that are similar) according to a distance factor, how small these superpixels can be, and how many total superpixels should be defined. This is shown in Fig. 2c. Then the DBSCAN learning method implements spectral clustering to group the superpixels according to a distance function that factors in both the color difference and the spatial difference between superpixels to determine whether to group them into a cluster. The determining factor is a threshold that when set at two different values differentiates between the fineness of the monolayer and the roughness of the multilayer. The fine and rough DBSCAN results are shown in Fig. 2d. This is when the multilayer is differentiated and the fine clusters, superpixel values, and an initial labeling are saved into matrices of the same size as the image. The labeling used was {1 = substrate, 2 = monolayer, 3 = multilayer}. The logic needed to be severely reworked in this section because the indexing was illegal, and the clusters were labeled in a confusing manner. Then the software performs a few checks to ensure all the pre-labeling is accurate before the full-sized image is displayed with the cluster boundaries and their labels as shown in Fig. 2e. Finally, the user is directed to label which sections should be part of the multilayer (Fig. 2f) that aren’t enclosed in the blue boundaries. This was useful for samples that consisted of more multilayer than substrate and confused the machine learning algorithms. Then the user was directed to state which clusters are a part of the monolayer. This takes some expertise from the user to identify which flakes are monolayers and which aren’t, but as stated before, the lightest contrast regions correspond to the thinnest layers. Finally, clusters that should be part of the background are corrected. The program displays the new hypothetical class boundaries and asks the user if they are happy with the results or want to restart. When the user stops retrying, the program saves the labels into a .csv, the original image, and the boundaries image just for the user to refer back to. If the original clusters and superpixels do not properly encompass all the necessary details in the sample, the hyperparameters for the SLIC and DBSCAN methods can be adjusted and rerun.

This process is very time-consuming and illustrates the necessity for a supervised learning model. As can be seen, the model cannot accurately incorporate all the fine details to identify monolayers as intuitive (yet tedious) as it seems for a human. However, with a subset of images, the supervised learning model should now “learn” what details are important to discern layer thickness.

Data augmentation

When the images are labeled, the labels and original images are fed into the data augmentation process shown in Fig. 3. This crops the images into a 100\(\times\)100 image. The cropping was done systematically by fitting in the rounded-up quotient of the original image size to the new cropped size by overlapping the last image with the second-to-last image. The cropping was also randomized to compare the results. Then the images were color-processed, then sheared in two directions and rotated. This resulted in four images for each crop and there was approximately six crops per image in the dataset we used of eighteen images leading to 408 total training images. In addition, the shearing was accomplished by affine2d and an imresize in MATLAB. However, due to pixel averaging this resulted in a region of zeros where the image is sheared. This was accounted for in the machine learning program by adding a new class with the label 4. Although neither 4 or 0 could arise from the labeling program, the machine learning struggled with labeling when the first class (0) was a placeholder and not present in all images. This was compared to leaving the new classification class out and keeping only three classes.

Models and results

Object segmentation models were surveyed and utilized to predict regions of monolayer, multilayer, and substrate. Object segmentation models utilize supervised learning to classify each pixel of an image into certain classes. In this work, two models were investigated: SegNet46and U-Net47. In addition, both 1D and 2D versions of U-Net were trained to compare performance on physics-based features versus image-based features respectively. The 1D U-Net model was motivated based on linear dependence of light transmittance on the number of layers48. In addition, since each row is extracted for each image, there are more samples for training a smaller model when compared to the 2D version, allowing for potentially better generalization and predictions.

Since this is a multi-class classification problem, cross-entropy loss was utilized as shown in Eq. 3. Cross-entropy measures the degree of randomness between the true labels (\(T_{ni}\)) and predicted labels (\(Y_{ni}\)) for N observations and K classes. Since the classes are unbalanced, \(w_i\) allows weighting49.

Two other loss functions that measure the overlap between the target and predictions - Jaccard index (Eq. 4a) and Dice similarity coefficient (Eq. 4b) were considered while training the model, but the best-performing models were trained with cross-entropy loss. Y and T denote an image and its corresponding ground truth, K is the number of classes, M is the number of elements (pixels) in Y, \(w_k\) is the class weight.

The best model was determined by evaluating various metrics, including overall accuracy and per-class accuracy. While overall accuracy may be higher for certain models, the actual performance could be worse due to differences in distribution of sample’s classes. Accuracy is not always the best measure for object segmentation problems, so errors such as Intersection-over-Union (IoU) which measures the overlap of predictions to labels were also monitored. We also used Precision, Recall, and F1 Score, which aided in understanding the model’s performance. Precision measures how precise each prediction is while Recall measures whether each class was classified correctly. F1 score is a measure of both Precision and Recall. In Table 1, 2D SegNet has the Mean IoU value in the Precision column and Mean BF score in the F1 Score column.

SegNet MATLAB

SegNet is a deep convolution neural network with an encoder-decoder architecture, utilizing max-pooling to up-sample in the decoder stage, reducing the model size as previous models utilized fully connected networks to up-sample29.

For encoding and decoding, the process involves three layers of convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU activation, followed by either a max-pooling or max-unpooling layer, respectively. The depth of the network depends on how many times it is down-sampled (equivalent to the number of times it is up-sampled), culminating in a softmax classification layer for pixel-wise classification. The primary objective is to minimize pixel variation within the same class while maximizing differentiation between different classes, thereby ensuring precise boundary delineation. Two critical parameters influencing this accuracy are the network depth (referring to the number of convolutional layers in both the encoder and decoder networks) and class weights46. SegNet’s structure favors the predominant class (e.g., background substrate) if there’s a disproportionate number of pixels in each class. To rectify this, smaller classes must be appropriately weighted in the loss function using a class weights array at the final pixel classification layer44.

Transfer learning was implemented by using a pretrained network stored in a .mat file instead of generating a new segmentation network. The fully connected layer needed to be removed and a new one connected to allow for retraining with a new dataset.

As previously discussed, the Jaccard index, also known as Intersection over Union (IoU), measures the percentage of overlap between expected and predicted class areas. When evaluating visual results, the average IoU across all three classes proved to be the most effective metric for comparing different implementations using the same original dataset. For assessing implementations with altered parameters, monolayer accuracy emerged as the primary metric. Less effective metrics included Weighted IoU, which averages IoU weighted by the number of pixels in each class, and Mean Boundary F1 Score, which assesses how well predicted boundaries match the correct boundaries. The variability of Mean Boundary F1 Score is illustrated in Tables 2 & 3, while the weighted average undermines the intent to appropriately handle larger class sizes. Visual comparisons were conducted by delineating predicted or labeled monolayer boundaries in green and multilayer boundaries in blue on the original images.

Two main categories of implementations were tested. The baseline model was the already trained model taken from the GitHub repository44. Initially, the baseline model was compared to implementations that used transfer learning and the newly labeled dataset. First the model was trained with the original three classes: monolayer, multilayer, and background substrate. And the rest of the models used the fourth class of shear as it visually performed better as can be seen in Table 2. The metrics could not capture the added class confusion in the shear region which would make the future implementations more confusing to visually compare. It does seem like the model still worked well in the relevant area. There were a large number of false positives in the normalized implementation so randomized cropping further improved the results as shown in Table 2. Additionally, the various TCD color maps were compared but did not perform well according to the metrics nor visually.

The visual results for normalized, random crop can be seen in Fig. 4a–c. However, the results are still not optimal which suggests that the dataset was too small. The models were then pre-trained with the labeled dataset of 1400 images from Ref.44. The performance of using transfer learning and not was compared. Table 3 shows that the use of transfer learning with normalized color preprocessing performed best as can be confirmed in Fig. 4.

2D U-Net

U-Net is a convolution neural network with an encoder-decoder architecture, similar to SegNet, but also utilizes copy-and-crop operations on certain feature maps, creating a U-shape47. 2D U-Net models were trained on the full images and labels. Different preprocessing and hyperparameter tuning were used to improve the model’s performance. Ultimately, the raw images normalized were found to produce the best performance. This may be due to the loss of certain features when moving to different color maps. One area of improvement would be to utilize the different channels between the color mappings rather than normalizing it to one value. This would increase the model’s size, but potentially improve the model’s accuracy. The results are listed in Table 4 and can be visualized in Fig. 5.

1D U-Net

Each row in each image was utilized in training. During inferencing, the 100×100 image was separated into 100 rows, where each row was inferenced, and the resulting output row was appended to the resulting image’s prediction. Hyperparameter tuning and different preprocessing was used to improve the model’s performance. The results are displayed in Table 5 and can be visualized in Fig. 6.

Labels and predictions using 1D U-Net for four microscopic imaging on different thickness (a)–(d). Using the same color scheme as 2D U-net where yellow is multilayer but green is monolayer. None of the predictions depict monolayers. Because they are generated line by line, the representation of the area is inadequate, resulting in regions that appear more streaky, as clearly seen in (b). The axis is labeled for spatial position.

The 1D model did not perform as well as the 2D model, primarily due to the loss of information vertically. Another setback was the time to inference the model was longer than the 2D model, despite the model and input being smaller. One potential reason for this would be the movement of memory in the processor outweighing the efficiency of the model. Despite this, the model was able to get meaningful results.

Conclusion and outlook

The best trained model classified the data classes in 2D, and encompassing all potential labels. However, refining data augmentation methods, particularly shear augmentation, could potentially obviate the need for four distinct classes.

Image normalization to the background proved more effective than any color processing method in most cases, except for one instance with the one-dimensional U-Net, possibly due to clearer differentiation between the background and monolayer/multilayer. For the sake of simplicity, only mapping of the pixel color to other color spaces (even though the total color difference calculation facilitated this) was used to extract contrast data. Other techniques such as using the raw TCD as an ML model input could lead to better labeling and more accurate model performance.

The labeling capability should be confirmed by a more sound method to remove errors introduced by subjectivity of the experimenter confirming boundaries. Across all experiments, transfer learning consistently outperformed other methods, even when the pretrained model had no direct relevance to 2D materials, as seen with the U-Net model. Additionally, the larger dataset yielded superior performance compared to the smaller, more carefully labeled dataset.

This study was limited to a single data source, restricting broader conclusions. However, that data source included great diversity of features, material types, and background samples from different experimental setups29. This allowed relatively high accuracy even for the small subset of 408 images that were manually labeled. The introduction of automated labeling capabilities allows for future exploration of how dataset diversity correlates with model accuracy. With the advantages of transfer learning, future research should analyze how well a model could be adapted to new datasets for specific materials and properties. This could demonstrate the potential for a universal database for two-dimensional material training networks.

Furthermore, expanding beyond monolayer and multilayer identification by iterating through the “define baseline labeling” step could reveal additional layers, typically up to a maximum of ten.

Lastly, model performance can be enhanced by fine-tuning hyperparameters and optimizing transfer learning through weight freezing strategies. This study proves that using object segmentation models makes for an accessible yet robust 2D material layer identification method. It only requires an optical microscope and access to one of many publicly available datasets for transfer learning23,35,44. As a result, two-dimensional materials can be more frequently used as a research material to further explore their advantages in the semiconductor industry or even other spheres of electronics and biomedicine.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/aramesh10/MLOC-Machine-Learning-Enabled-Fast-Optical-Identification-and-Characterization-of-2D-Materials

References

Han, T. et al. Investigation of the two-gap superconductivity in a few-layer NbSe\(_2\)-graphene heterojunction. Physical Review B 97(6), 060505 (2018).

X. Chen, et al. “Probing the electronic states and impurity effects in black phosphorus vertical heterostructures,” 2D Materials, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 015012, 2016.

Wu, Y. et al. Negative compressibility in graphene-terminated black phosphorus heterostructures. Physical Review B 93(3), 035455 (2016).

Wang, K. L., Wu, Y., Eckberg, C., Yin, G. & Pan, Q. Topological quantum materials. MRS Bulletin 45(5), 373–379 (2020).

B. Zhang, P. Lu, R. Tabrizian, P. X.-L. Feng, and Y. Wu, “2D magnetic heterostructures: spintronics and quantum future,” npj Spintronics, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 6, 2024.

H. Zhong, P. Plummer, Douglas Z.and Lu, Y. Li, P. A. Leger, and Y. Wu, “Integrating 2D magnets for quantum devices: from materials and characterization to future technology,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12136, 2024.

Wu, Y. et al. Large exchange splitting in monolayer graphene magnetized by an antiferromagnet. Nature Electronics 3(10), 604–611 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Néel-type skyrmion in WTe\(_2\)/Fe\(_3\)GeTe\(_2\) van der Waals heterostructure. Nature Communications 11(1), 3860 (2020).

Ajayan, P., Kim, P. & Banerjee, K. Two-dimensional van der Waals materials. Physics Today 69(9), 38–44 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Induced Ising spin-orbit interaction in metallic thin films on monolayer WSe\(_2\). Physical Review B 99(12), 121406 (2019).

Y. Hou, F. Nichele, H. Chi, A. Lodesani, Y. Wu, M. F. Ritter, D. Z. Haxell, M. Davydova, S. Ilić, O. Glezakou-Elbert, A. Varambally, F. Bergeret, A. Kamra, L. Fu, P. A. Lee, and M. J. S., “Ubiquitous superconducting diode effect in superconductor thin films,” Physial Reveview Letters, vol. 131, no. 2, p. 027001, 2023.

Gerstner, E. Nobel Prize 2010: Andre Geim & Konstantin Novoselov. Nature Physics 6(11), 836–836 (2010).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The Rise of Graphene. Nature Materials 6(3), 183–191 (2007).

Zhang, Z., Yang, X., Liu, K. & Wang, R. Epitaxy of 2D Materials Toward Single Crystals. Advanced Science 9(8), 2105201 (2022).

Tong, X., Liu, K., Zeng, M. & Fu, L. Vapor-phase Growth of High-quality Wafer-scale Two-dimensional Materials. InfoMat 1(4), 460–478 (2019).

Walsh, L. A. & Hinkle, C. L. van der Waals Epitaxy: 2D Materials and Topological Insulators. Applied Materials Today 9, 504–515 (2017).

Cai, Z., Liu, B., Zou, X. & Cheng, H.-M. Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth and Applications of Two-dimensional Materials and Their Heterostructures. Chemical Reviews 118(13), 6091–6133 (2018).

Yu, J., Li, J., Zhang, W. & Chang, H. Synthesis of High Quality Two-dimensional Materials via Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chemical Science 6(12), 6705–6716 (2015).

S. Bhowmik and A. G. Rajan, “Chemical Vapor Deposition of 2D Materials: A Review of Modeling, Simulation, and Machine Learning Studies,” Iscience, vol. 25, no. 3, 2022.

Alexeev, E. M. et al. Imaging of Interlayer Coupling in van der Waals Heterostructures using a Bright-field Optical Microscope. Nano letters 17(9), 5342–5349 (2017).

Kenaz, R. et al. Thickness Mapping and Layer Number Identification of Exfoliated van der Waals Materials by Fourier Imaging Micro-ellipsometry. ACS Nano 17(10), 9188–9196 (2023).

Jie, W., Yang, Z., Bai, G. & Hao, J. Luminescence in 2D Materials and van der Waals Heterostructures. Advanced Optical Materials 6(10), 1701296 (2018).

Dong, X. et al. 3D Deep Learning Enables Accurate Layer Mapping of 2D Materials. ACS Nano 15(2), 3139–3151 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. High-quality Sandwiched Black Phosphorus Heterostructure and Its Quantum Oscillations. Nature Communications 6(1), 7315 (2015).

D. L. Duong, S. J. Yun, and Y. H. Lee, “van der Waals Layered Materials: Opportunities and Challenges,” ACS Nano, vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 11 803–11 830, 2017.

Kim, D. S. et al. Surface Oxidation in a van der Waals Ferromagnet Fe\(_{3-x}\)GeTe\(_2\). Current Applied Physics 30, 40–45 (2021).

Wu, Y., Wang, W., Pan, L. & Wang, K. L. Manipulating Exchange Bias in a van der Waals Ferromagnet. Advanced Materials 34(12), 2105266 (2022).

Mao, Y., Wang, L., Chen, C., Yang, Z. & Wang, J. Thickness Determination of Ultrathin 2D Materials Empowered by Machine Learning Algorithms. Laser & Photonics Reviews 17(4), 2200357 (2023).

Han, B. et al. Deep-Learning-Enabled Fast Optical Identification and Characterization of 2D Materials. Advanced Materials 32(29), 2000953 (2020).

Wei, J. et al. Machine Learning in Materials Science. InfoMat 1(3), 338–358 (2019).

Morgan, D. & Jacobs, R. Opportunities and Challenges for Machine Learning in Materials Science. Annual Review of Materials Research 50, 71–103 (2020).

Duanyang, L. & Zhongming, W. Application of Supervised Learning Algorithms in Materials Science. Frontiers of Data and Domputing 5(4), 38–47 (2023).

J. Schmidt, M. R. Marques, S. Botti, and M. A. Marques, “Recent Advances and Applications of Machine Learning in Solid-State Materials Science,” npj Computational Materials, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 83, 2019.

N. Dihingia, G. A. Vázquez-Lizardi, R. J. Wu, and D. Reifsnyder Hickey, “Quantifying the Thickness of WTe\(_2\) using Atomic-resolution STEM Simulations and Supervised Machine Learning,” The Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 160, no. 9, 2024.

S. Masubuchi, E. Watanabe, Y. Seo, S. Okazaki, T. Sasagawa, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, and T. Machida, “Deep-learning-based image segmentation integrated with optical microscopy for automatically searching for two-dimensional materials,” npj 2D Materials and Applications, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1–9, 2020.

Y. Zhu, E. R. Antoniuk, D. Wright, F. Kargar, N. Sesing, A. D. Sendek, T. T. Salguero, L. Bartels, A. A. Balandin, E. J. Reed, and F. H. da Jornada, “Machine-Learning-Driven Expansion of the 1D van der Waals Materials Space,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 127, no. 44, pp. 21 675–21 683, 2023.

Solís-Fernández, P. & Ago, H. Machine Learning Determination of the Twist Angle of Bilayer Graphene by Raman Spectroscopy: Implications for van der Waals Heterostructures. ACS Applied Nano Materials 5(1), 1356–1366 (2022).

Li, W. & Yang, C. Thermal Conductivity of van der Waals Heterostructure of 2D GeS and SnS based on Machine Learning Interatomic Potential. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 35(50), 505001 (2023).

B. Sattari Baboukani, Z. Ye, K. G Reyes, and P. C. Nalam, “Prediction of Nanoscale Friction for Two-dimensional Materials using a Machine Learning Approach,” Tribology Letters, vol. 68, pp. 1–14, 2020.

Gao, L., Ren, W., Li, F. & Cheng, H.-M. Total Color Difference for Rapid and Accurate Identification of Graphene. ACS Nano 2(8), 1625–1633 (2008).

H. Li, J. Wu, X. Huang, G. Lu, J. Yang, X. Lu, Q. Xiong, and H. Zhang, “Rapid and reliable thickness identification of two-dimensional nanosheets using optical microscopy,” ACS nano, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 10 344–10 353, 2013.

U. Carion and F. Schultz, “Cielab.io,” https://github.com/ucarion/cielab.io, 2013.

Li, Y. et al. Rapid identification of two-dimensional materials via machine learning assisted optic microscopy. Journal of Materiomics 5(3), 413–421 (2019).

Y. Yang, “Smart classification of 2d nano-materials,” https://github.com/yafangy/Nanomaterial_DeepLearning, 2018.

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. Journal of Big Data 6(1), 1–48 (2019).

Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A. & Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 39(12), 2481–2495 (2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., Brox, T. & “U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation,” in Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention-MICCAI,. 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18. Springer 2015, 234–241 (2015).

Y. Niu, S. Gonzalez-Abad, R. Frisenda, P. Marauhn, M. Drüppel, P. Gant, R. Schmidt, N. S. Taghavi, D. Barcons, A. J. Molina-Mendoza, S. M. De Vasconcellos, Bratschitsch, D. P. De Lara, M. Rohlfing, and A. Castellanos-Gomez, “Thickness-dependent Differential Reflectance Spectra of Monolayer and Few-layer MoS\(_2\), MoSe\(_2\), WS\(_2\) and WSe\(_2\),” Nanomaterials, vol. 8, no. 9, p. 725, 2018.

MathWorks. (2024) Cross-entropy loss for classification tasks - matlab crossentropy.

Acknowledgements

Support from UF Gatorade award and Research Opportunity Seed Fund are kindly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Wu conceived the ideas and supervised the project. P. Leger leads manuscript writing and discussions on results, with help from A. Ramesh and T. Ulloa. P. Leger, A. Ramesh, and T. Ulloa wrote and implemented the code.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leger, P.A., Ramesh, A., Ulloa, T. et al. Machine learning enabled fast optical identification and characterization of 2D materials. Sci Rep 14, 27808 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79386-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79386-z