Abstract

A DC microgrid with renewable energy sources can achieve reduced current ripple, higher efficiency, faster dynamics, high voltage gain, and less operational stress by interfacing with an interleaved boost converter (IBC). The stability of an IBC linked to a DC microgrid supplying a constant power load (CPL) can be imperceptibly guaranteed by a conventional controller. A tightly regulated CPL with nonlinear and negative incremental impedance characteristics will lead to stability issues. Uncertainties such as load and line variations will further affect the stability of the system. A nonlinear passivity-based control algorithm requires more attention than a traditional controller to achieve the stability of power converters. This article explains the Brayton–Moser (BM) passivity-based controller (PBC) for a 2-level interleaved boost converter (IBC) interfaced DC microgrid with CPL. The suggested controller can achieve high signal stability by injecting a series-connected virtual impedance. The stability of the proposed controller has been assessed using the Lyapunov stability approach. A BM passivity-based controller for a 2-level IBC with CPL has been derived and investigated under various operating modes using MATLAB and Simulink. It was also observed that the proposed system achieves at least \(2\%\) improvement in efficiency and \(50\%\) reduction in current ripple. To evaluate the performance of BM Passivity-based controller, a comparative analysis was performed between the suggested controller and the traditional PI controller, which is also included in this paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, attention towards DC microgrids has increased due to their ability to integrate smoothly with energy storage systems (ESS) and renewable energy sources (RESs). Conventional boost converters were utilized in DC microgrids to boost the voltage from the source to the DC bus. The limited voltage gain and constraints on the power density of the boost converter make it undesirable for applications requiring high power. To improve voltage gain, a transformer can be used, but it will further degrade the efficiency of the system due to leakage inductance. So in the DC microgrid, an IBC has been introduced for reduced ripple current and improved power density1. IBC has the ability to reduce current ripple, have faster dynamics, reduce weight and size, and improve efficiency2,3,4.

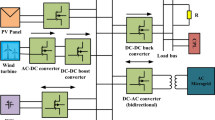

The schematic structure of the DC microgrid is illustrated in Fig. 1. Where a DC–DC converter connects the RES and ESS to the DC microgrid. RESs are mainly wind turbines and PV panels; ESSs consist of batteries, a DC generator, a super capacitor, and a fuel cell. A closely regulated DC/DC or DC/AC converter is employed to meet the majority of the load in the DC microgrid5,6,7. Those types of loads are commonly known as constant power loads. High-power microgrid applications can be achieved through an IBC, even though control and stability issues persist. Non-linearity and negative incremental impedance of tightly regulated converter loads such as CPL lead to instability8. The DC microgrid supplied by an IBC experiences drops in voltage quality and a reduction in stability margin. Also, uncertainty in the parameters of the IBC enhances the stability issues of DC Microgrid9,10,11,12. In order to overcome these challenges, a control technology for an IBC is required. The literature presents a variety of control topologies designed for DC microgrids to mitigate the negative incremental impedance effect of CPL13,14,15,16,17. Basically, controllers can be classified into two types, such as linear control techniques and nonlinear control techniques18. Linear controllers use passive and active damping control techniques. The addition of passive elements such as an LC filter or RC damper to a physical system will improve damping. This is known as the passive damping method. In19, authors have proposed the active damping method. But tuning a linear controller for a large system is difficult. So linear control can achieve small signal stability. And linear controllers cannot guarantee the stability of IBCs integrated into DC microgrids under different operating conditions.

To achieve large signal stability, researchers proposed a nonlinear controller. In20, for a CPL powered by a DC/DC boost converter, the authors have proposed a type-II fuzzy controller. But the input or output information of the system is an intelligent control parameter. So it is required an online tuning for intelligent control parameters21. A model predictive controller with HOSMO is proposed in22. However, a trial-and-error method is proposed for parameter tuning in23,24,25. Power factor enhancement using Finite State Model Predictive Control is addressed in26. The suggested controller demonstrates excellent performance in both conditions such as transient and steady-state, remaining resilient to parameter fluctuations. In27 and28, backstepping controller techniques are implemented in DC microgrids with CPL. It is a high gain control method, so it will deteriorate the robustness of the system against noise measurements29. In30 to achieve stability in the system, the authors have suggested a Sliding Mode Controller for boost or buck converters. However, the requirement of an extra sensor leads to enhanced implementation costs and degraded ripple filtering effects31. An H\(\infty\)-based controller for an uncertain CPL is proposed32 for incorporation into the DC microgrid. The proposed controller features easy implementation and reduced implementation costs. However, the design control algorithm, the Glover-Doyle Optimization Algorithm, has a higher-order denominator, which makes implementation more difficult. A similar control scheme is employed by the synergetic control strategy33 and sliding mode control (SMC).A fixed switching frequency can be produced without experiencing chattering issues. However, susceptibility to parameter uncertainties and load disturbances exists. Recently, passivity-based controllers have drawn more attention to different areas such as EV battery chargers, robot arms, switched power converters, etc. PBC34 is a theoretical tool based on the concept of energy dissipation. To achieve system stability, improve the damping of the system by adding virtual resistance through the PBC technique. So the system becomes passive against any uncertainty. Port Controlled Hamilton (PCH)-based PBC and Euler Lagrange (EL) PBC35 techniques have been introduced for DC microgrids that use CPL. In36, an adaptive PBC for a DC/DC boost power converter has been proposed by the author. In37, PBC for a DC/DC boost converter is suggested for MPPT applications in DC microgrids. All these techniques have advantages such as global stability, simplicity and ease of design, improved control robustness, etc.38.

Mainly conventional DC/DC boost converters have been focused on all nonlinear controllers, as proposed in32,39,40,41,42,43,44. Different configurations of converters were discussed45, including the bridge less SEPIC PFC converter and the full bridge buck converter. However, these converters are specifically used for arc welding power supplies. But regarding high gain and multilevel IBCs, they have been rarely discussed46. By using a 2-level IBC, a CPL can acquire all advantageous characteristics, such as less ripple, a high power rating, and an improved step-up ratio. An onboard integrated charger for electric vehicle batteries that employs Brayton–Moser (BM) PBC technology has been discussed in47 and48. In EL PBC, the damping factor selection method is not proper, but it can be overcome by the BM PBC method. The state variables of the EL method and PCH method are flux and charge to control the current and voltage of the system. However, the system’s voltage and current are directly state variables of BM PBC. So it is easy to measure the control variables in BM PBC49.

To address the stability issues mentioned, a BM PBC is proposed for stabilizing the 2-level IBC integrated DC microgrid feeding CPL. Stability challenge in DC microgrids featuring CPL during line and load variations is addressed in this article. Therefore, a robust controller with more advantages than other nonlinear controllers is proposed in this article. For example, the Brayton–Moser passivity-based controller features direct passivity shaping, greater robustness to disturbances, a simpler design process, and ensures stability directly. Additionally, using an IBC, compared to conventional converters, results in lower current ripple due to the distribution of current across multiple phases. This reduction in losses leads to increased efficiency and higher power density. This paper presents a proposed controller that can achieve robust and efficient performance under uncertainty in parameters. The improved dynamic characteristics can be achieved by the proposed controller through a parallel connection with a PI controller.

The organization of this article is as follows: Sects. 2 and 3 discuss the mathematical modeling of conventional boost converters and 2-level IBCs using the BM-PBC method. The different operating modes of a 2-level IBC are also included. Along with stability analysis, the control topology of BM-PBC for a 2-level IBC is described in Sect. 4. Section 5 narrated the comparative analysis and simulation results of the recommended controller and the conventional controllers. Section 6 summarizes the concluding points.

Modeling of DC microgrid powered by boost converter

Ortega has proposed passivity-based controller in50. This controller algorithm uses the passivity concept to achieve system stabilization. To maintain the voltage regulation in the system, two techniques, such as energy shaping and the injection of damping, are incorporated into the passivity-based controller algorithm. By using the Brayton–Moser equation, A nonlinear DC/DC boost converter with a CPL is being modeled. Here, average modeling of boost converter has been explained using the BM framework. Figure 2 illustrates a schematic diagram of a boost converter powers the DC microgrid.

The BM function was introduced as a mixed potential function \(P(i_L,V_o)\) and a differential equation governed by a nonlinear equation circuit is,

where the supply voltage is E, the voltage across DC bus is \(V_o\), the inductor current is \(i_L\), the mixed potential function is P, and L, C are used to denote the value of inductance and capacitance of the system.

The 2-state variables of the system should be considered as \(x_1=i_L\) and \(x_2=V_o\), as depicted in Fig. 2. Where CPL is linked to the DC source via a DC/DC boost converter. From49 the following representation, BM equation of the boost converter can be provided:

A series damping injection is given to the system, where \(R_i\) is the virtual damping factor introduced in series with the system’s inductance to alter the energy of the system. Then dynamic equation of a closed-loop system is,

where \(\tilde{i_L}=i_L-i_{Ld}\) and \(\tilde{V_o}=V_o-V_{cd}\). Substracting (3) from (1), then,

From (4) dynamic equation of boost converter could be given as,

Control law(\(\mu _i\)) for boost converter from BM equation can be described after solving (5)

Modelling of 2 level IBC feeding DC microgrid

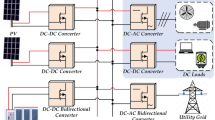

The schematic illustration for a DC microgrid powered by a 2-level IBC is illustrated in Fig. 3. The system’s topology includes DC sources, 2-level interleaved boost converters (IBC), and a constant power load (CPL). The 2-level IBC consists of 2-inductors \(L_1\) and \(L_2\) which are connected in parallel. Switch \(Q_1\) is connected to switch \(Q_2\). Diode \(D_1\) is also connected in parallel with diode \(D_2\). All components used for the circuit are identical to ensure interleaved operation. As all elements connected in parallel, there was a parallel path between input and output. Signals given into two switches should be \(180^{\circ }\) out of phase.

Operating modes of 2 level IBC

For the given constant switching time (\(T_s\)) and supply voltage (E), the assumption has been made that it has ideal passive elements and switching devices. And during different switching times, characteristics of current, voltage, and gate signal are shown in Fig. 4. Here, 2-level IBC has 4-operating modes without considering the parasitic elements.All operating modes have been mentioned in Fig. 5. States of switches (ON/OFF) can be decided by discrete switching functions such as \(\sigma _1\) and \(\sigma _2\). The switch is on for \(\sigma T_s\) and off for \((1-\sigma ) T_s\) for one sampling period, \(T_s\).

Waveform of voltage, current and gate signal of interleaved converter51.

BM review and modelling in 2 level IBC

An alternative technique to the Lagrangian and switched port Hamiltonian formulations is offered by Brayton–Moser52,53. The Brayton–Moser function, referred to as the Mixed-Potential Function (MPF) P (\(i_L\), \(V_C\)), is defined as follows:

where the total supplied power to the voltage sources and current sources is denoted by \(P_E\) and \(P_J\), respectively. The dissipative current potential and the dissipative voltage potential are denoted as \(P_R\) and \(P_G\), while \(P_T\) represents the internal power. In accordance with Brayton–Moser theory, the differential equation that depicts the nonlinear electric circuit dynamic behavior is:

where voltage across DC bus and current through inductor are depicted as \(V_c\) and \(i_L\). The C and L are value of capacitance and value of inductance respectively. The term P is a mixed potential function, can be represented simply as \(dP=dG-dJ\). G represents content and J represents co-content energy, where \(dG=<i_L,dV_c>\) and \(dJ=<V_c,di_L>\). MPF for four operating modes can be derived as follows: when \(\sigma _1=1\) and \(\sigma _2=0\) is the first mode of operation where the status of switches (\(S_1\), \(S_2\)) is (ON,OFF). The MPF for mode 1 is,

2 level IBC under different operating modes54.

when \(\sigma _1=0\) and \(\sigma _2=1\) is the second mode of operation where the status of switches (\(S_1\), \(S_2\)) is (OFF,ON). The MPF for mode 2 is,

when \(\sigma _1=1\) and \(\sigma _2=1\) is the third mode of operation where the status of switches (\(S_1\), \(S_2\)) is (ON,ON). The MPF for mode 3 is,

when \(\sigma _1=0\) and \(\sigma _2=0\) is the fourth mode of operation where the status of switches (\(S_1\), \(S_2\)) is (OFF,OFF). The MPF for mode 4 is,

MPF of four different modes can be rewritten in terms of switching signal (\(\sigma _1,\sigma _2\)) as follows,

State space equation of the model can be derived from (8) and (13)

Design of Brayton–Moser passivity-based controller

The control algorithm for an IBC integrated with a DC microgrid feeding CPL is designed using a passivity-based controller. Here, virtual damping factor is introduced to achieve passive characteristics of the system.

Design of BM PBC for 2 level IBC

Dynamic system in the BM form can be written as,

where \(z=[z_1 z_2 z_3]^T\) are state variables and \(z_1=i_{L_1}\), \(z_2=i_{L_2}\) and \(z_3=V_{c}\). The requisite average state space variable directory has been given as,

For a single switching cycle, \(z_d\) is the required average state space variable directory. \(z=[i_{L1d} i_{L2d} V_{cd}]^T\). The state variable’s error trajectory is given by \(\tilde{z}=z-z_d\) . And Eq. (17) explains the error dynamic of the system.

However, the error dynamics also include virtual damping according to PBC theory, so the (17) as,

The dissipation factor injected into the system is represented by \(P_{Ri}\) and \(P_{Gi}\).

Analysis of stability

By using Lyapunov’s stability theorem, the stability of the PBC approach has been verified for nonlinear systems. Consider a positive definite energy function \(H_f\) for the proposed error dynamic system, given by

where \(H_f\) is defined as a positive definite function (\(H_f>0\)), otherwise \(H_f=0\) when \(\tilde{i}_{L1}=\tilde{i}_{L2}=\tilde{V_c}=0\).

Now the derivative \(H_f\) can be written as,

From error dynamics \(L_1\dot{\tilde{i}}_{L1}\), \(L_2 \dot{\tilde{i}}_{L2}\) and \(C\dot{\tilde{V_c}}\) can be written as:

Substituting (21) into (20) then,

Here, the damping resistances \(R_{i1}\) and \(R_{i2}\) are positive (\({R_{i1}}>0\) and \({R_{i2}}>0\)). So it is clear that \(\dot{H_f}\) is negative always. Thus, the rate of stored energy decreases as time progresses, which is typically regarded as a stable characteristic. So from (19) and (22), the system stability has been proven.

Design of controller with series damping

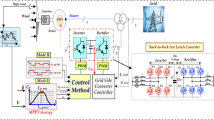

To obtain the control function, the energy of the system is modified by the PBC control algorithm. Virtual damping is used by the system to reshape the energy. Therefore, the system can incorporate virtual damping either in series or in parallel. The series connection is with the input inductor, and the parallel connection is with the output capacitor. Here we are mainly discussing series damping injection. Since the load and capacitor are already linked in parallel, parallel damping injection is inappropriate for this system. Figure 6 depicts an illustration of the BM-PBC in a 2-level IBC.

Consider \(P_{Gi}=0\) for the injection of series damping to modify the system’s energy. Then, the system’s closed-loop dynamics from (18) can be formulated as:

The dynamic equation of closed-loop system can be derived by subtracting (23) from (15),

Where \(R_{i1}\) and \(R_{i2}\) are injected damping resistances, which are connected in series with the input inductors \(L_1\) and \(L_2\). \(P_{Ri1}\) and \(P_{Ri2}\) are given below.

From (24), closed-loop dynamics have been described as follows:

By considering \(i_{L1d}=i_{L2d}=\frac{1}{2}I_d\sin {\omega t}\) and \(V_{cd}=V_d\) to achieve the system’s objectives, Solving (26) yields the following control law.

Here, the inductor currents, \(i_{L1}=i_{L2}\), and series damping injection, \(R_{i1}=R_{i2}\), are the same, so all switches have the same duty ratio. And the values of series damping injection can affect the duty ratio, so the selection of series damping injection should be based on the following conditions:

A schematic representation of the BM PBC is depicted in Fig. 7. Here PI controller is integrated with the BM PBC to enhance the dynamic characteristics of the aforementioned controller. The system stabilizes rapidly, and steady-state errors are easily removed because of the PI controller addition. Therefore, the control law can be modified by the incorporation of the PI controller, which can be represented as:

Where \(\sigma _{new}\) is the new control law, \(k_p\) and \(k_e\) are PI controller gains, and the output voltage error is \(e_i(t)=V_{ref}-V_0\).

Results and discussion

By using MATLAB simulink and simpower system toolboxes, a simulink model of the proposed BM-PBC controller for conventional and 2-level IBC has been developed. The system parameter specifications include input voltage (E) of 100–200 V, boost converter inductance (L): 375 \(\upmu H\), capacitance (C): 238.28 \(\upmu F\) with switching frequency (\(T_s\)): 20 KHz, and 2 level interleaved converter inductance (\(L_1\)) and (\(L_2\)): 757 \(\upmu H\), capacitance (C):1171 \(\upmu F\) with switching frequency (\(T_s\)): 20 KHz. The system is stabilized by using the suggested controller with a 5kw CPL and an output voltage of 400V. Validation of the BM PBC robustness has been conducted for different load and line variation conditions.

Performance analysis of BM-PBC for boost converter

Dynamic characteristics and steady-state performance of a boost converter with the BM-PBC algorithm feeding a DC microgrid with CPL are investigated through different characteristic waveforms. Figure 8 illustrates the steady-state characteristics of boost converter with BM-PBC. In the figure, waveform of current through the inductor \(i_L\), voltage across the load \(V_o\), and load power \(P_{CPL}\) are shown. It has been observed that the system maintains the DC bus voltage as \(V_O=400\) V with CPL. Figure 9 depicts dynamic features of a boost converter under variations in CPL. Here CPL has increased from 5 kw to 10 kw at 0.5 s. It is evident that DC bus voltage was maintained at \(V_o=400\) V during CPL variation. Figure 10 depicts dynamic characteristics of a boost converter with input voltage variation. At 3 s input voltage has changed from 100 to 200 V. But DC bus voltage \(V_o=400\) V during input supply variations.

Performance analysis of BM-PBC for IBC during steady-state condition

MATLAB software is used to perform a simulation study of BM-PBC-based controller for two-level IBC used for DC microgrid feeding CPL. Figure 11 shows the performance of BM-PBC for 2 level IBC for 5KW feeding CPL at 100V dc supply voltage during steady state. It is evident that the system achieved value at steady state for DC bus voltage quickly, and overall steady-state performance of the system is also improved.

Performance under line and load variations for IBC

Figures 12, 13, and 14 illustrate the effectiveness of the BM-PBC controller against uncertainty such as line and load variation for 2-level IBCs feeding DC microgrid. By varying the voltage from its nominal value of 100 V, Fig. 12 illustrates the waveforms of the 2-level IBC for the BM-PBC controller. The supply voltage is changed to 200 V in 0.3 seconds. Based on the Fig. 12, it is evident that DC bus voltage reached its steady-state value following the variation in input voltage, where power remains constant. Therefore, a wide range of source voltage variations can be handled by the suggested controller.

Dynamic characteristics of the 2-level IBC under CPL variation are illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14. Here, the constant power load has decreased from 5 to 2.5 kW at 0.5 s in Fig. 13. Then the load has increased from 5 KW to 10 KW at 0.5 sec in Fig. 14. During all these load variations, the desired DC bus voltage of 400V has been achieved quickly. Hence, the proposed controller can achieve good transient performance under load variation.

Comparison between different controllers

BM PBC and the PI controller have been compared for performance analysis. Figure 15 depicts the analysis between the BM-PBC and PI controllers. The trial-and-error method is utilized to adjust the gains of the PI controller, specifically \(K_p\) and \(K_i\). The superiority of the proposed controller can be easily analyzed from Table 1. A comparative analysis is conducted between the recommended controller and the traditional PI controller, focusing on transient characteristics such as settling time ,rise time,peak overshoot, peak time and inductor ripple current, as mentioned in Table 1. Figure 15 shows the comparison between the PI controller and the proposed controller during load variations. Where stable operating point is achieved by the BM-PBC controller faster than by the PI controller. Figure 16 depicts the comparative analysis between different controllers such as PI controller, EL-PBC and proposed controller. From this comparative study, the proposed controller can maintain system stability faster during uncertainty such as line and load disturbances compared to other controllers. Additionally, unlike a PI controller, overall system stability can be assured.

The suggested controller highlights the benefits of utilizing the BM-PBC along with IBC. From the above figures, we can conclude that BM-PBC can achieve better dynamic performance than EL-PBC. Figure 17 presents the advantage of using an IBC over a conventional boost converter. Here, BM-PBC for IBCs can maintain the stability of the system during any uncertainty with improved steady-state characteristics than BM-PBC with boost converters.

To understand the improved performance of the BM-PBC against the PI controller, Fig. 18 has been mentioned. Here, during different input voltages, the system efficiency in the presence of both controllers has been mentioned. From the figure, greater efficiency is exhibited by the proposed controller than PI controller during large variations in input voltage.

Figure 19 illustrates the comparison between performance analysis of BM-PBC and PI controller. Here, the efficiency of the system during different loads has been explained. So it can be understood that the efficiency can be varied from 91 to 96 % during load power variations.

Conclusion

In this article, the mathematical modeling and development of a BM-PBC controller for 2-level IBC have been proposed. Improved steady-state performance can be achieved with the integration of suggested controller and PI controller. The PBC control method relies on the principle of energy conservation, so stability is achieved through virtual damping injection. Among other PBC techniques, BM-PBC is different that it is used control variable as a physical quantity such as current and voltage. But in the EL and PCH methods, flux and charge are the control variables. So it is used to measure the variable indirectly.By using BM-PBC, large signal stability is achieved by the introduction of series damping into the system. By using Lyapunov stability criteria, system stability also confirmed. The BM-PBC controller for 2-level IBC is simulated in MATLAB Simulink and validated for performance. From the comparative analysis of PI controller and suggested controller, it can be observed that BM-PBC can achieve a good steady state and transient performance under various operating points. The overall efficiency of the system has improved by a minimum \(2\%\) and a minimum \(50\%\) of the current ripple has been reduced by using the suggested controller. In the future, proposed system can be developed for hybrid DC microgrids with CPL and constant voltage loads.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Villarreal-Hernandez, C. A. et al. Minimum current ripple point tracking control for interleaved dual switched-inductor dc-dc converters. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 68, 175–185 (2020).

Liu, J., Liu, Z., Chen, W. & Su, H. Passivity-based control for interleaved double dual boost converters in dc microgrids supplying constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 8, 1642–1655 (2021).

DebBarman, S., Namrata, K., Kumar, N. & Meena, V. Optimising power distribution systems: solar-powered capacitors and cost reduction through meta-heuristic methods. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Inf. 12, 188–212 (2024).

Shipra, K., Maurya, R. & Sharma, S. N. Port-controlled hamiltonian-based controller for an interleaved boost pfc converter. IET Power Electron. 13, 3627–3636 (2020).

Gui, Y. et al. Large-signal stability improvement of dc-dc converters in dc microgrid. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 36, 2534–2544 (2021).

Mathur, A. et al. Data-driven optimization for microgrid control under distributed energy resource variability. Sci. Rep. 14, 10806 (2024).

Varshney, T. et al. Fopdt model and chr method based control of flywheel energy storage integrated microgrid. Sci. Rep. 14, 21550 (2024).

Rai, I. & Anand, R. Design of suboptimal controller for improved dynamic response in dc microgrid linked to multiple constant power loads. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE), 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

PV, N. Comparative analysis of different control strategies in microgrid. Int. J. Green Energy 18, 1249–1262 (2021).

Chaudhary, R., Singh, V. P., Mathur, A., Meena, V. P. & Murari, K. Truncation-based approximation of autonomous microgrid. In 2024 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/KPEC61529.2024.10676110 (2024).

Rai, I., Ravishankar, S. & Anand, R. Review of dc microgrid system with various power quality issues in “real time operation of dc microgrid connected system. Majlesi J. Mechatron. Syst. 8, 35–44 (2019).

Meena, G., Saini, D., Meena, V., Mathur, A. & Singh, V. A modified implicit z-bus method for an unbalanced hybrid ac-dc microgrids. In 2023 IEEE IAS Global Conference on Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Technologies (GlobConHT), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Rai, I., Anand, R., Lashab, A. & Guerrero, J. M. Hardy space nonlinear controller design for dc microgrid with constant power loads. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 133, 107300 (2021).

Gutierrez, M., Saathoff, E. K., Ponce, E. & Leeb, S. B. Sub line-frequency stability analysis of single-phase constant power loads using envelope impedance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37, 13310–13318 (2022).

He, B., Chen, W., Li, X., Shu, L. & Ruan, X. A power adaptive impedance reshaping strategy for cascaded dc system with buck-type constant power load. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37, 8909–8920 (2022).

Meena, V. & Singh, V. Controller design for a tito doha water treatment plant using the class topper optimization algorithm. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 16097–16107 (2023).

Sulligoi, G. et al. Multiconverter medium voltage dc power systems on ships: Constant-power loads instability solution using linearization via state feedback control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 5, 2543–2552 (2014).

Rai, I., Rajendran, A., Lashab, A. & Guerrero, J. M. Nonlinear adaptive controller design to stabilize constant power loads connected-dc microgrid using disturbance accommodation technique. Electr. Eng. 1–16 (2023).

Guan, Y., Xie, Y., Wang, Y., Liang, Y. & Wang, X. An active damping strategy for input impedance of bidirectional dual active bridge dc-dc converter: Modeling, shaping, design, and experiment. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 68, 1263–1274 (2020).

Vafamand, N., Yousefizadeh, S., Khooban, M. H., Bendtsen, J. D. & Dragičević, T. Adaptive ts fuzzy-based mpc for dc microgrids with dynamic cpls: Nonlinear power observer approach. IEEE Syst. J. 13, 3203–3210 (2018).

Yousefizadeh, S. et al. Ekf-based predictive stabilization of shipboard dc microgrids with uncertain time-varying load. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 7, 901–909 (2018).

Kowsari, E. et al. A novel stochastic predictive stabilizer for dc microgrids feeding cpls. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 9, 1222–1232 (2020).

Gheisarnejad, M., Mohammadzadeh, A. & Khooban, M.-H. Model predictive control based type-3 fuzzy estimator for voltage stabilization of dc power converters. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69, 13849–13858 (2021).

V.P. Meena, V. S. & Guerrero, J. M. Investigation of reciprocal rank method for automatic generation control in two-area interconnected power system. Math. Comput. Simul. 225, 760–778 (2024).

Xu, Q., Yan, Y., Zhang, C., Dragicevic, T. & Blaabjerg, F. An offset-free composite model predictive control strategy for dc/dc buck converter feeding constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35, 5331–5342 (2019).

Bouafassa, A., Rahmani, L., Babes, B. & Bayindir, R. Experimental design of a finite state model predictive control for improving power factor of boost rectifier. In 2015 IEEE 15th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (EEEIC), 1556–1561 (IEEE, 2015).

Wu, J. & Lu, Y. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode control for boost converter with constant power load. IEEE Access 7, 50797–50807 (2019).

Li, X. et al. A novel assorted nonlinear stabilizer for dc-dc multilevel boost converter with constant power load in dc microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35, 11181–11192 (2020).

Xu, Q., Zhang, C., Wen, C. & Wang, P. A novel composite nonlinear controller for stabilization of constant power load in dc microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10, 752–761 (2017).

Ghorbal, M. J. B., Moussa, S., Ziani, J. A. & Slama-Belkhodja, I. A comparison study of two dc microgrid controls for a fast and stable dc bus voltage. Math. Comput. Simul. 184, 210–224 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Qiao, W. & Ha, D. A sliding-mode duty-ratio controller for dc/dc buck converters with constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 50, 1448–1458 (2013).

Boukerdja, M. et al. H\(\infty\) based control of a dc/dc buck converter feeding a constant power load in uncertain dc microgrid system. ISA Trans. 105, 278–295 (2020).

Ahmadi, F., Batmani, Y., Bevrani, H., Yang, T. & Cui, C. Finite-time synergetic controller design for dc microgrids with constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 14, 3352–3361 (2023).

Hassan, M. A. et al. Adaptive passivity-based control of dc-dc buck power converter with constant power load in dc microgrid systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Topics Power Electron. 7, 2029–2040 (2018).

Namazi, M. M., Nejad, S. M. S., Tabesh, A., Rashidi, A. & Liserre, M. Passivity-based control of switched reluctance-based wind system supplying constant power load. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 65, 9550–9560 (2018).

Hassan, M. A., Su, C.-L., Chen, F.-Z. & Lo, K.-Y. Adaptive passivity-based control of a dc-dc boost power converter supplying constant power and constant voltage loads. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69, 6204–6214 (2021).

Hassan, M. A. & He, Y. Constant power load stabilization in dc microgrid systems using passivity-based control with nonlinear disturbance observer. IEEE Access 8, 92393–92406 (2020).

Jeung, Y.-C., Lee, D.-C., Dragičević, T. & Blaabjerg, F. Design of passivity-based damping controller for suppressing power oscillations in dc microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 36, 4016–4028 (2020).

Akhbari, A. & Rahimi, M. Control and stability analysis of dfig wind system at the load following mode in a dc microgrid comprising wind and microturbine sources and constant power loads. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 117, 105622 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Stability analysis of dc microgrids with constant power load under distributed control methods. Automatica 90, 62–72 (2018).

Farsizadeh, H., Gheisarnejad, M., Mosayebi, M., Rafiei, M. & Khooban, M. H. An intelligent and fast controller for dc/dc converter feeding cpl in a dc microgrid. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 67, 1104–1108 (2019).

Meena, V., Singh, V. P., Padmanaban, S. & Benedetto, F. Rank exponent-based reduction of higher order electric vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73, 12438–12447. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3387975 (2024).

Baskaran, J. et al. Cost-effective high-gain dc-dc converter for elevator drives using photovoltaic power and switched reluctance motors. Front. Energy Res. 12, 1400651 (2024).

Srinivasan, M. & Kwasinski, A. Control analysis of parallel dc-dc converters in a dc microgrid with constant power loads. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 122, 106207 (2020).

Bouafassa, A., Fernández-Ramírez, L. M. & Babes, B. Power quality improvements of arc welding power supplies by modified bridgeless sepic pfc converter. J. Power Electron. 20, 1445–1455 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Towards large-signal stabilization of interleaved floating multilevel boost converter enabled high-power dc microgrids supplying constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. (2023).

Shipra, K., Maurya, R. & Sharma, S. N. Brayton-moser passivity based controller for electric vehicle battery charger. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 6, 40–51 (2021).

Shipra, K. & Maurya, R. Brayton-moser passivity-based controller for an on-board integrated electric vehicle battery charger. J. Energy Stor. 75, 109652 (2024).

Jeltsema, D. & Scherpen, J. M. Tuning of passivity-preserving controllers for switched-mode power converters. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 49, 1333–1344 (2004).

Ortega, R. & Spong, M. W. Adaptive motion control of rigid robots: A tutorial. Automatica 25, 877–888 (1989).

Zaman, H., Zheng, X., Yang, M., Ali, H. & Wu, X. A sic mosfet based high efficiency interleaved boost converter for more electric aircraft. J. Power Electron. 18, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.6113/JPE.2018.18.1.23 (2018).

Brayton, R. K. & Moser, J. K. A theory of nonlinear networks. i. Q. Appl. Math. 22, 1–33 (1964).

Brayton, R. K. & Moser, J. K. A theory of nonlinear networks. ii. Q. Appl. Math. 22, 81–104 (1964).

Shenoy, K. L. et al. Design and implementation of interleaved boost converter. Int. J. Eng. Technol. (IJET) 9, 496–502 (2017).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study, conception, and design. all authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

The authors transfer to Springer the publication rights and warrant that our contribution is original.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nithara, P.V., Anand, R., Ramprabhakar, J. et al. Brayton–Moser passivity based controller for constant power load with interleaved boost converter. Sci Rep 14, 28325 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79405-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79405-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A passivity based nonlinear controller for hybrid DC microgrid with constant power loads

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Adaptive control of DC-DC power converter: design and experimental investigation with constant power load

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Empowering net zero energy grids: a comprehensive review of virtual power plants, challenges, applications, and blockchain integration

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)

-

A novel hybrid methodology for wind speed and solar irradiance forecasting based on improved whale optimized regularized extreme learning machine

Scientific Reports (2024)