Abstract

To study the influence of the thickness of a weak interlayer on the deformation and failure characteristics of composite rock mass. Based on the measured data of sand-mudstone interbedded floor rock mass in the Yima mining area, Henan Province, China. Using quartz sand, gypsum, and cement as similar materials make composite rock-like specimens with weak interlayers. The mechanical properties, deformation evolution process, failure characteristics, and acoustic emission laws of rock samples with different interlayer thicknesses under uniaxial compression were studied using the digital image correlation method and acoustic emission monitoring technology. The results show that: (1) With an increase in the thickness of the weak interlayer, there is a corresponding decrease in the compressive strength of the specimen. When the thickness of the weak interlayer exceeds 5 cm, the compressive strength of the composite rock specimen is even less than that of the single weak rock-like. (2) Under uniaxial compression conditions, the strain concentration zone first appears in the weak interlayer part of the composite rock-like specimen. As the pressure continues to increase, the specimen is the first to fail at the position of the maximum strain concentration zone. (3) The thickness of the weak interlayer is an important factor affecting the failure mode of composite rock-like specimens. With the increase of the thickness of the weak interlayer, the composite rock-like specimens change from overall failure to local failure. (4) With the increase of the thickness of the weak interlayer in the middle of the composite rock specimen, the maximum value of the energy released by the single acoustic emission event and the maximum value of the cumulative acoustic emission energy decrease during the compression failure process. The research results can provide a reference for the manufacture of composite rock mass with a weak interlayer and the deformation and failure analysis of composite rock mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lithology of the roadway floor in the Yima mining area of Henan Province is complex, and its structure is mostly layered with overlapping sand-mudstone floors1,2,3,4. The mechanical properties and failure characteristics of a layered floor are significantly different from those of a single lithology floor when a floor rock burst accident occurs. In practical engineering, the monitoring and treatment of layered floors should employ methods and measures distinct from those used for single lithologic floors, so it is of great significance to study layered rock mass.

It is difficult to obtain unlimited rock samples or enough natural rock materials with a special structure when sampling underground and preparing rock samples in the laboratory5. In experimental studies, rock-like materials often replace natural rock materials6,7,8,9. This research method is widely used in the field of geotechnical mechanics’ research. Many experts and scholars have done a lot of experimental and theoretical research on this10,11,12,13. Liu et al.14 fabricated composite specimens with different strength combinations using cement, gypsum, and sand as similar materials, and studied the effect of material strength ratio on the mechanical properties of composite specimens under uniaxial compression. Hu et al.15 made layered rock mass using rock-like materials and studied the creep properties of layered rock mass. Tang et al.16 used 3D printing technology to make rock-like specimens with complex joints and studied the influence of joints on rock-like strength. Chai et al.17 studied rock-like specimens’ damage and deformation characteristics in uniaxial compression experiments using the digital image correlation method (DIC). Luo et al.18 fabricated rock-like specimens consisting of alternating soft and hard interbedded layers and investigated the deformation and failure characteristics of these specimens under uniaxial compression. Niu et al.19 used quartz sand, barite powder, and gypsum as similar materials to prepare fractured rock-like samples, and obtained the deformation characteristics of fractured rock mass and the acoustic emission laws of crack propagation under uniaxial compression. Zhang et al.20 prepared rock-like specimens with weak interlayers in different inclination angles and studied the damage characteristics and fracture behavior of the specimens under uniaxial compression. Li et al.21 carried out uniaxial compression and digital image correlation tests on double-layer composite rock-like specimens. They explored the effects of bedding planes and joints on rock-like strength. Landis et al.22 used ultrasonic technology to quantify the attenuation of ultrasonic waves in concrete materials. Some characteristics of the attenuation curve can be related to the degree of inhomogeneity in the material. Lacidogna et al.23 used acoustic emission and dynamic identification techniques to study the stress-dependent damage process of pre-notched concrete beams in four-point bending tests. Aggelis et al.24 use acoustic emission to classify the active cracking mode, which can characterize the current fracturing condition inside the material and issue a warning before the final failure. Lockner25 reviews the successes and limitations of AE studies as applied to the fracture process in rock, emphasizing the ability to predict rock failure. Tandon et al.26 explored the stability of cracks in gel materials by using bending tests of specimens under three-point and four-point loading conditions. Niccolini et al.27 associated material failure with changes in the electrical properties of materials to study the possible critical behavior in the fracture process of rock and cement materials.

In summary, scholars have done a lot of research on layered rock mass, but there are few reports on the systematic study of the mechanical properties, deformation evolution characteristics, and acoustic emission law of composite rock mass with weak interlayers. In this paper, the composite rock mass with a weak interlayer is taken as the research object, and quartz sand, cement, and gypsum are used as similar materials to make a composite specimen of a hard-soft-hard three-layer structure composed of two different strength materials. Combined with the digital image correlation method and acoustic emission technology, the influence of interlayer thickness on the mechanical properties, deformation evolution, failure characteristics, and acoustic emission energy of composite rock samples under uniaxial compression was studied.

Experiment methods

Experimental proportion scheme

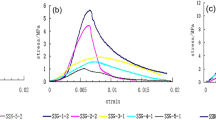

In this paper, the sand-mudstone interbedded floor in the Yima mining area of Henan Province is taken as the research background. The horizontal interbedded rock mass is mainly studied because the interbedded floor is of slow dip angle. The mechanical parameters of floor sandstone and mudstone measured before the experiment are shown in Table 1, and rock-like specimens are made based on this. In the experiment, P.O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement and quartz sand with particle sizes less than 0.5 mm were selected as sandstone-like materials. P.O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement, quartz sand with particle size less than 0.5 mm, and gypsum were selected as mudstone-like materials. After a large number of previous matching experiments, the final matching scheme is determined as shown in Table 2, and the stress-strain curve of the rock-like specimen is shown in Fig. 128. As shown in Fig. 1 the variation characteristics of stress-strain curves of rock-like materials are very similar to those of typical rocks. The compressive strength and elastic modulus of sandstone-like and mudstone-like materials are within the range of the measured mechanical parameters of the original rock. Therefore, sandstone-like and mudstone-like materials can be used to make sand-mudstone overlapping composite rock mass specimens.

Specimen preparation

The mould for preparing the specimen is a cuboid hard plastic mould with dimensions of 5 cm × 5 cm × 10 cm. In the experiment, sandstone-like materials were selected as hard rock materials and mudstone-like materials were selected as soft rock materials. The composite rock-like specimens with hard-soft-hard three-layer structures were made by layered pouring. The thickness of the interlayers is 2, 3, 4, and 5 cm respectively, and there are 4 specimens in each group. The schematic diagram of the composite rock-like specimens is shown in Fig. 2.

The pouring moulds and some specimens are shown in Fig. 3. The specific pouring steps are as follows:

-

1.

Apply lubricating oil on the inner surface of the mold to facilitate later demolding.

-

2.

The sandstone-like experimental materials were weighed according to the material ratio, and the materials were mixed evenly in the container. Add an appropriate amount of water to the container and stir well. The sandstone-like material is poured at the bottom layer, and the material is compacted during the pouring process. The first pouring height is 4 cm, and then the upper surface of the pouring material is smoothed.

-

3.

After 30 min, the mudstone-like experimental material was weighed according to the ratio, and the 2 cm mudstone-like material was continuously poured at the interface of the sandstone-like material according to step 2.

-

4.

After 10 min, the sandstone-like material was prepared according to step 2, poured onto the top of the mould, and the surface of the material was stamped and flattened. At this time, the model was 10 cm high.

-

5.

Repeat steps 1–4 to prepare composite rock-like specimens with weak interlayer thicknesses of 3, 4, and 5 cm, respectively. Four specimens were prepared in each group.

-

6.

The specimens were demoulded after standing at room temperature for 24 h. The specimens were numbered and cured for 28 days.

-

7.

The specimens with a good forming effect and smooth surface were selected, and the ends were polished to ensure that the non-parallelism of the two ends of the specimen was within 0.05 mm.

-

8.

A layer of black paint was evenly sprayed on the surface of any side of the specimen. After the black paint was dried, white scattered spots were randomly sprayed on the side of the black paint. Finally, the specimen was dried.

Experimental system

The experimental system consists of a loading system, a DIC monitoring system, and an acoustic emission monitoring system. The experimental system is shown in Fig. 4. The loading system is the Meters electronic universal test machine. The displacement loading speed range of the test machine is 0.001–1000 mm/min, and the maximum load is 100 kN. The DIC monitoring system includes four parts: A camera, light source, tripod, and computer. The acoustic emission monitoring system selects the Beijing Soft Island DS5-16B full information 16-channel acoustic emission signal instrument.

Before the experiment, an acoustic emission sensor was pasted on the three side surfaces of the unsprayed speckle on the specimen, 30 mm away from the two end surfaces. Each specimen was equipped with six acoustic emission sensors. The position diagram of the acoustic emission sensor is shown in Fig. 5.

In the experiment, the acoustic emission sampling frequency is set to 3 MHz, and the threshold value is set to 100 mV, which can ensure that the external noise is shielded. Adjust the position of the light source and the camera until the camera can capture the scattered spots on the surface of the specimen. The test machine first needs to use the force loading control mode when loading the specimen, and slowly load to 10 N. At this time, the upper-pressure head of the press is in contact with the upper surface of the specimen. Then the specimen was loaded at a displacement loading speed of 0.5 mm/min until the specimen was destroyed. Pressure loading, DIC monitoring, and acoustic emission monitoring are carried out at the same time, and the system automatically records the experimental data.

Results and analysis

Stress-strain curves analysis

Four uniaxial compression tests were carried out on the specimens of each interlayer thickness, and the compressive strength of the specimen was replaced by the specimen closest to the average compressive strength. Figure 6 shows the stress-strain curves of composite rock-like specimens with different interlayer thicknesses. As shown in Fig. 6 the stress-strain curves of the composite rock specimen are similar to the stress-strain curves of the typical rock. During the compression process, the specimens experienced four stages: initial compaction stage, elastic deformation stage, plastic deformation stage, and failure stage.

At the initial stage of loading, the composite rock-like specimen is in the initial compaction stage, and the stress-strain curve is concave downward. At this time, the primary pores and cracks inside the rock gradually close under the action of compressive stress. With the increase of the thickness of the weak interlayer, the plasticity of the layered composite rock becomes stronger, and the duration of the curve compaction stage increases. With the increase of axial pressure, the specimen enters the elastic deformation stage. The stress-strain curve of the rock-like specimen at this stage is approximately an inclined straight line. As shown in Fig. 6 the slope of the straight line decreases with the increase of the thickness of the interlayer. In other words, the elastic modulus of composite rock decreases with the increase of interlayer thickness. As the loading progresses, the specimen enters the plastic deformation stage. At this time, the stress-strain curve of the specimen is upward convex, and the slope of the curve is decreasing. New cracks and fissures are generated inside the rock, and the plastic deformation generated at this stage is irreversible. Finally, the load on the specimen reaches its peak stress, and the specimen enters the failure stage. The specimen begins to fail from the inside, but the outside remains intact. The specimen still has a certain degree of bearing capacity. The specimen is destroyed completely as the loading continues.

Strength characteristics analysis

The compressive strength changes of composite rock-like specimens with different interlayer thicknesses are shown in Fig. 7. When the interlayer thickness is 0 cm, 2 cm, 3 cm, 4 cm, and 5 cm, the average compressive strength of the corresponding composite rock-like specimens is 28 MPa, 26 MPa, 21 MPa, 18 MPa, and 14 MPa, respectively. It shows that when the rock specimen contains a weak interlayer, the composite rock specimen’s compressive strength decreases with the increase of interlayer thickness. The thickness of the weak interlayer of the composite specimen is negatively correlated with its compressive strength. Combining the above analysis to fit the data, the equation is as follows:

where y is compressive strength, MPa; x is the thickness of interlayer, cm.

When the thickness of the interlayer is 2 cm, the average compressive strength of the composite rock specimen is 26 MPa, which is close to the hard rock (sandstone-like) compressive strength. When the thickness of the interlayer is 4 cm, the average compressive strength of the composite rock specimen is 18 MPa, which is close to the compressive strength of the soft rock (mudstone-like). When the thickness of the interlayer is 5 cm, the average compressive strength of the composite rock specimen is 14 MPa, which is less than the soft rock (mudstone-like) compressive strength of 16.9 MPa.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the thickness of the weak interlayer in the composite rock specimen has an important influence on the compressive strength of the composite specimen. When the thickness of the weak interlayer exceeds 5 cm, the compressive strength of the composite specimen is even smaller than the strength of the single weak rock-like. When the thickness of the weak interlayer increases to 5 cm, the fracture of the rock-like first appears on the contact surface of the soft and hard rock strata. Then the fracture rapidly expands to the weak interlayer, which causes the failure of the specimen. At this time, the load on the specimen does not exceed the compressive strength of the soft rock. From the above analysis, the interface effect of the weak interlayer is the main reason why the compressive strength of the composite rock specimen is less than the compressive strength of the soft rock.

Deformation evolution characteristics

The deformation evolution characteristics of composite rock-like specimens under uniaxial compression were analyzed by the digital image correlation method. Figure 8 shows the strain cloud diagram in the vertical direction when the peak strength is 30%, 60%, 90%, and 100%, respectively.

It can be seen from Fig. 8(a) that when the axial load is loaded to 30% of the peak strength, the strain of the interlayer of the composite rock-like specimen with 2 cm interlayer is larger, and the average value is about 1.5 × 10− 3. The strain at both ends of the specimen is small, and the strain value at the upper end is greater than that at the lower end. When the axial load reaches 60% of the peak strength, the compressive strain of the whole specimen increases, and the maximum strain value in the middle of the specimen reaches 2.8 × 10− 3. When the axial load is loaded to 90% of the peak strength, an obvious strain concentration zone appears at the 2 cm interlayer in the middle of the specimen, and the maximum strain reaches 6.3 × 10− 3. When the load increases to the peak strength, a strain concentration zone with an inclination angle of 45 degrees appears in the middle interlayer, where the strain is the largest, and the middle interlayer is the first to fail.

According to the analysis of Fig. 8(b), when the interlayer thickness is 3 cm and the load value reaches 30% of the peak strength, the strain concentration zone first appears in the middle of the specimen slightly below the position. The scope of the strain concentration zone continues to increase as the loading progresses. When the load value reaches 90% of the peak strength, an obvious strain separation zone can be observed near the contact surface between the interlayer and the upper and lower hard rock materials.

As shown in Fig. 8(c) when the thickness of the interlayer increases to 4 cm, the strain concentration zone first appears in the upper part of the specimen. When the load value reaches 60% of the peak strength, the strain concentration zone is evenly concentrated in the middle of the specimen. When the load value reaches 90% of the peak strength, the strain in the middle of the specimen reaches 8.6 × 10− 3. When the load increases to the maximum peak strength, a strain concentration zone with an inclination angle of 45 degrees appears in the middle of the weak interlayer, and the specimen fails along this.

According to the Fig. 8(d) when the thickness of the interlayer increases to 5 cm, the strain concentration zone is mainly concentrated near the upper and lower contact surfaces of the soft and hard rock layers. As the loading progresses, the strain concentration zone shrinks to the right, and the maximum strain value increases. When loaded to the peak strength of the rock, the shape of the strain concentration zone is similar to a triangle, which is located in the middle of the specimen on the right side, and the specimen seriously failed at this position.

In summary, under uniaxial compression, the composite rock-like specimen with a weak interlayer first appears to strain the concentration area in the weak interlayer part. With the increase of the thickness of the weak interlayer, the strain concentration zone appears more obvious, and the strain value of this part is larger than that of other positions. The weak interlayer reaches its maximum load capacity as the pressure continues to increase. At this time, the strain value of the weak interlayer reaches the maximum, and the specimen first failed in the position of the maximum strain concentration zone. The elastic modulus and compressive strength of soft rock are lower than those of hard rock, while the deformation under the same pressure is greater for soft rock. Additionally, soft rock reaches its compressive limit before hard rock, making it more prone to failure. When the thickness of the interlayer is large, the specimen is first broken on the contact surface of the soft and hard interlayer, so that the specimen is destroyed when the compressive strength of the soft rock is not reached.

Failure characteristics

The changing image of the composite rock-like specimen during the compression process is captured in real time using a camera. The failure characteristics of the specimens are shown in Fig. 9.

When the thickness of the weak interlayer in the specimen is 2 cm and 3 cm, similar failure characteristics are observed. Take an example with a weak interlayer thickness of 2 cm. From the analysis of Fig. 9(a). With the increase of axial load, the expansion phenomenon occurs in the weak interlayer position, and then cracks occur in the middle of the specimen. As the axial pressure continues to increase, the crack expands to both ends of the specimen. When the axial pressure continues to increase, macroscopic cracks go through the entire specimen. When the thickness of the interlayer is 4 cm and 5 cm, the failure characteristics of the specimens are similar. So take an example with a weak interlayer thickness of 4 cm. According to the analysis of Fig. 9(c), it is evident that under the action of uniaxial compression, the deformation of the interlayer position in the middle of the specimen increases, showing an obvious expansion phenomenon. As the loading progresses, cracks are first generated near the contact surface of the soft and hard interlayers. When the axial pressure continues to increase, the crack begins to expand rapidly to the weak interlayer and its vicinity, and the specimen is destroyed along the crack direction. The failure of the specimen is concentrated in the weak interlayer position of the specimen, and the hard rock part at both ends is slightly failed. The crack does not penetrate the whole specimen.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that when the thickness of the weak interlayer is relatively small, the weak interlayer and the upper and lower hard rock strata tend to be whole, resulting in penetrating cracks and the overall failure of the specimen. When the thickness of the weak interlayer is relatively large, the mechanical properties of the weak interlayer are more prominent. The specimen is seriously failed in the weak interlayer, and the rest is slightly failed. The compressive strength of the specimen increases when the proportion of weak interlayer is small. A large amount of elastic energy is accumulated in the weak interlayer during uniaxial compression. When the load reaches the compressive limit of the weak interlayer, the energy stored in the weak interlayer is suddenly released. The energy is transmitted to the remaining rock strata in the form of stress waves so that the remaining rock strata fail when they do not reach their compressive limit. When the proportion of weak interlayers is high, the compressive strength of the specimen decreases, resulting in a reduced accumulation of elastic energy within the weak interlayer. The energy release is not enough to make the rest of the rock strata fail when they do not reach their compressive limit. Therefore, when the thickness of the weak interlayer accounts for a large proportion, local failure occurs in the specimen. In summary, the proportion of weak interlayer is a key factor affecting the failure characteristics of composite rock specimens.

Evolution law of acoustic emission energy

During the compression process of rock-like materials, the change in the internal structure of the materials will release elastic waves of different frequencies and different energies, which is called rock-like acoustic emission29. By monitoring the acoustic emission of rock-like specimens during compression, it can gain insights into the internal failure mechanisms of these specimens and provide a comprehensive explanation of the entire process of rock-like failure30,31,32,33. Acoustic emission energy is the energy carried by sound waves generated by phenomena such as deformation or fracture inside the material during the acoustic emission process. The schematic diagram of the acoustic emission energy principle is shown in Fig. 10.

During the compression process of specimens with different interlayer thicknesses, the curves of stress, acoustic emission energy, and cumulative acoustic emission energy with time are shown in Fig. 11.

The analysis of Fig. 11 reveals a consistent acoustic emission energy evolution law among composite rock-like specimens with varying weak interlayer thicknesses under uniaxial compression. According to the distribution characteristics of acoustic emission energy, the evolution process of acoustic emission energy can be divided into the following three stages: I, the quiet period of acoustic emission energy, II, the steady growth period of acoustic emission energy, III, the burst period of acoustic emission energy. The above three stages have a good corresponding relationship with the compaction stage, elastic-plastic deformation stage, and failure stage of the specimen in the compression process. During the initial loading stage, the specimen undergoes an initial compaction process. Under axial pressure, the internal pores and cracks gradually compacted without any occurrence of new cracks. At this stage, there are no or only a few acoustic emission events, and the energy of a single acoustic emission event is small, the cumulative acoustic emission energy is at a low level, and the acoustic emission energy is in a quiet period. With the increase of axial pressure, the specimen enters the elastic-plastic deformation stage. At this stage, new cracks and fissures are generated inside the specimen, and acoustic emission events occur frequently. The energy of a single acoustic emission event increases, the cumulative acoustic emission energy continues to increase, and the cumulative acoustic emission energy increase is greatly improved compared with the quiet period of acoustic emission energy. The acoustic emission energy enters a stable growth period. As the pressure continues to increase, the specimen enters the failure stage. The pores and cracks inside the specimen are connected and penetrated to each other, and macroscopic cracks are generated on the surface of the specimen. When loaded near the ultimate compressive strength of the specimen, acoustic emission events occur frequently and the energy of a single acoustic emission event increases greatly. When loading to the ultimate compressive strength of the composite rock-like specimen, the specimen is destroyed and accompanied by high-energy acoustic emission events. The value of single acoustic emission energy reaches the maximum, and the cumulative acoustic emission energy curve has a surge point at this time. In the failure stage of the specimen, the acoustic emission energy of the specimen enters the burst period.

Figure 11(a)-(d) shows the relationship between acoustic emission energy, cumulative energy, stress, and time when the thickness of the weak interlayer in the middle of the composite rock-like specimen is 2 cm, 3 cm, 4 cm, and 5 cm. The maximum acoustic emission energy of a single acoustic emission event in the compression process of specimens with different interlayer thicknesses is 18,900 mV·ms, 14,466 mV·ms, 12,113 mV·ms, and 9697 mV·ms respectively, and the maximum cumulative energy of acoustic emission is 84,570 mV·ms, 76,717 mV·ms, 70,318 mV·ms and 64,795 mV·ms. The comparative analysis shows that with the increase of the thickness of the weak interlayer in the composite rock-like specimen, the maximum value of the single acoustic emission event release energy and the maximum value of the cumulative acoustic emission release energy during the compression failure process of the specimen is reduced. The thickness ratio of the weak interlayer has an important influence on the energy release of the specimen during uniaxial compression.

Conclusions

Based on the research background of the sand-mudstone overlapping floors in the Yima mining area of Henan Province, we made composite rock-like specimens with weak interlayers. The mechanical experiments of specimens under uniaxial compression were carried out by using the digital image correlation method and acoustic emission monitoring technology. The conclusions were as follows.

-

1.

The compressive strength of composite rock-like specimens is negatively correlated with the thickness of weak interlayer. When the thickness of the weak interlayer exceeds 5 cm, the compressive strength of the composite specimen is even less than the uniaxial compressive strength of the weak rock-like specimen.

-

2.

Under uniaxial compression, the strain concentration zone first appears in the weak interlayer part of the composite rock specimen, and the larger the thickness of the weak interlayer, the more obvious the strain concentration zone appears. As the load reaches the ultimate load of the weak interlayer, the strain value reaches the maximum, and the specimen first fails in the maximum strain concentration zone position.

-

3.

When the thickness of the weak interlayer is relatively small, the weak interlayer and the upper and lower hard rock layers tend to be whole, and the composite rock-like specimen undergoes overall failure under uniaxial compression. When the thickness of the weak interlayer is relatively large, the mechanical properties of the weak interlayer are more prominent, and the specimen produces local failure in the weak interlayer. The proportion of weak interlayers is a key factor affecting the failure characteristics of composite rock-like specimens.

-

4.

According to the distribution characteristics of acoustic emission energy in the uniaxial compression process of composite rock-like specimens, the evolution law of acoustic emission energy can be divided into three stages: the quiet period of acoustic emission energy, the steady growth period of acoustic emission energy, and the burst period of acoustic emission energy. The thickness of the weak interlayer is negatively correlated with the maximum value of the energy released by the single acoustic emission event and the maximum value of the cumulative acoustic emission energy during the compression failure process of the specimen.

In this paper, we only study the influence of single interlayer thickness on the deformation and failure of composite rock mass with weak interlayer. The research on multi-layer interlayer and different interlayer dip angles for composite rock mass is not involved, which will be the direction and focus of our future research work.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Huang, Q. & Cheng, J. Research on stress distribution and failure characteristics of coal mining floor in soft-hard alternant strata. Rock. Soil. Mech. 38 (S1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.S1.004 (2017).

Yang, R., Zhu, Y. & Li, Y. Stress distribution and damage characteristics of roadway floor in layered rock mass. J. Chin. Uni Min. Tech. 49 (04), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.13247/j.cnki.jcumt.001166 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Three-dimensional physical model experiment of mining-induced deformation and failure characteristics of roof and floor in deep underground coal seams. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 150, 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2021.04.029 (2021).

Triantafyllidis, T. & Gerolymatou, E. Estimation of the strength of Stratified Rock Mass. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 47, 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-013-0431-6 (2014).

Tatone, B., Abdelaziz, A. & Grasselli, G. Example framework for evaluation of synthetic rock-like materials as applied to a commercial gypsum cement. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 169, 105445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105445 (2023).

Kong, Y., Ruan, H. & Wang, Z. Selection and mechanical properties testy of similar brittle rock-like model materials of basalt. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 45 (11), 2308–2318. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE20220984 (2023).

Cheng, X., Sun, H., Pu, Y., Guo, J. & Qiao, W. Mechanical and energetic properties of rock-like specimens under water-stress coupling environment. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 14 (5), 1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-024-01766-y (2024).

Zhang, Y., Cao, Z. & Shi, X. Study on the Water-Physical properties of the cement-plaster Bonded Rock-Like materials. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021 (8863064). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8863064 (2021).

Luo, K., Zhao, G. & Zeng, J. Fracture experiments and numerical simulation of cracked body in rock-like materials affected by loading rate. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 37 (08), 1833–1842. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2018.0080 (2018).

Lian, S. et al. Investigation of the mechanical behavior of rock-like material with two flaws subjected to biaxial compression. Sci. Rep. 14, 14136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64709-x (2024).

Li, K., Zhao, Z., Ma, D., Liu, C. & Zhang, J. A. Emission and mechanical characteristics of Rock-Like Material containing single Crack under Uniaxial Compression. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47 (4), 4749–4761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-06251-w (2022).

Cebasek, T. & Fruehwirt, T. Investigation of creep behaviours of gypsum specimens with flaws under different uniaxial loads. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 10 (1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2017.11.002 (2018).

Kumar, S., Tiwari, G., Parameswaran, V. & Das, A. Dynamic mechanical behaviour of rock-like materials with a flaw under different orientation and infill conditions. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (9), 345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03365-3 (2023).

Liu, X., Ye, Y. & Wang, Q. Mechanical properties of similar material specimens of composite rock masses with different strengths under uniaxial compression. Rock. Soil. Mech. 38 (S2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.S2.025 (2017).

Hu, B., Yang, S., Xu, P. & Cheng, J. Cyclic loading–unloading creep behavior of composite layered specimens. Acta Geophys. 67 (2), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-019-00261-x (2019).

Tang, Q., Xie, W., Jing, S., Wang, X. & Su, Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the mechanical behavior of Rock-Like Material with Complex Discrete joints. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57 (7), 4493–4511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-03784-y (2024).

Chai, J., Liu, Y., Yi, B., Zhang, D. & Du, W. Application of Digital Image Correlation Technique for the damage characteristic of Rock-like specimens under Uniaxial Compression. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020 (8857495), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8857495 (2020).

Luo, P., Wang, L., Li, D., Yang, J. & Lv, X. Deformation and failure mechanism of horizontal soft and hard interlayered rock under uniaxial compression based on digital image correlation method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 142, 106823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106823 (2022).

Niu, Y. et al. Influence of the strength of rock-like models on the local deformation field and acoustic emission characteristics. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (8), 334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03355-5 (2023).

Zhang, L., Jing, H., Meng, Y. & Liu, H. Experimental study on the damage characteristics and fracture behaviour of Rock-like materials with weak interlayer zones. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 26 (9), 4157–4167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-022-2367-4 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Mechanical behavior and failure characteristics of double-layer composite rock-like specimens with two coplanar joints under uniaxial loading. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China Trans. 33 (9), 2815–2831. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(23)66300-9 (2023).

Landis, E. & Shah, S. Frequency-dependent stress wave attenuation in cement-based materials. J. Eng. Mech. ASCE. 121 (6), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733- (1995). 9399(1995)121:6(737).

Lacidogna, G., Piana, G. & Carpinteri, A. Acoustic emission and modal frequency variation in concrete specimens under four-point bending. Appl. Sci. 7 (4), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7040339 (2017).

Aggelis, D., Mpalaskas, A., Ntalakas, D. & Matikas, T. Effect of wave distortion on acoustic emission characterization of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.03.013 (2012).

Lockner, D. The role of acoustic emission in the study of rock fracture. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geo Abs. 30 (7), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(93)90041-B (1993).

Tandon, S., Faber, K. & Bažant, Z. Crack stability in the fracture of cementitious materials. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 370, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1557/PROC-370-387 (1994).

Niccolini, G., Potirakis, S., Lacidogna, G. & Borla, O. Criticality Hidden in Acoustic emissions and in changing Electrical Resistance during fracture of Rocks and Cement-based materials. Materials. 13 (24), 5608. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13245608 (2020).

Dai, S., Sun, Q., Hao, R. & Xiao, Y. Study on failure characteristics and Acoustic Emission laws of Rock-like specimens under Uniaxial Compression. Appl. Sci. 14, 8893. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14198893 (2024).

Cheng, A., Dai, S. & Zhang, Y. Study on size effect of damage evolution of cemented backfill. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 38 (S1), 3053–3060. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2018.1413 (2018).

Pan, J., Yuan, S., Jiang, T. & Cui, C. Experimental study on crack characteristics and acoustic emission characteristics in rock-like material with pre-existing cracks. Sci. Rep. 11, 23790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03162-6 (2021).

Zhao, K. et al. Study on energy dissipation and acoustic emission characteristics of fiber tailings cemented backfill with different ash-sand ratios. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 174, 983–996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.04.038 (2023).

Guo, D., Zhang, W., Chen, Q. & Wang, Z. F. Mechanism and Acoustic Emission characteristics of coal–rock samples. J. Min. Sci. 58 (3), 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1134/S106273912203005X (2022).

Wang, X., Wen, Z., Jiang, Y. & Huang, H. Experimental study on Mechanical and Acoustic Emission characteristics of Rock-Like Material under non-uniformly distributed loads. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 51 (3), 729–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-017-1363-3 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U183920051), Innovative Talents of Colleges and Universities in Liaoning Province (No. LR2019031), Basic Project of Education Department of Liaoning Province (No. LJ2019JL006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.S. conceived the experiments, Q. S. and R. H. conducted the experiments, and Q. S., S. D., and Y.X. analyzed the results. All authors contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Q., Dai, S., Hao, R. et al. Study on mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of composite rock mass with different thicknesses of weak interlayer. Sci Rep 14, 27835 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79408-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79408-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical properties and constitutive model of rock-like materials under acid corrosion

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)

-

Influence of Discontinuity Types on the Mechanical Behavior of Rock Fracture: Insights from the Modified Field-Enriched Finite-Element Method Simulation

Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering (2025)