Abstract

Tenebrio molitor, which is rich in various nutrients, and its polysaccharides, as significant bioactive substances, exhibit strong antioxidant effects. This study utilized defatted T. molitor as raw material and employed an ultrasound-assisted extraction method. The factors considered include extraction temperature, time, ultrasound power, and liquid-to-feed ratio, with the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides as the response value. Based on single-factor experiments and response surface methodology, the optimal extraction parameters for T. molitor polysaccharides were determined. Following purification, protein removal, and dialysis to eliminate impurities, the structure of the extracted polysaccharides was preliminarily investigated using infrared spectroscopy. Their antioxidant activities were explored by measuring their DPPH·, OH·, and ABTS+· radical scavenging abilities and Fe3+ reducing power. The results indicated that the optimal conditions for ultrasound-assisted extraction were an extraction temperature of 75 °C, an extraction time of 150 min, an ultrasound power of 270 W, and a liquid-to-feed ratio of 15:1 mL/g, yielding a polysaccharide extraction rate of 9.513%. Infrared spectroscopy analysis revealed the presence of pyranose sugars with main functional groups including C-O, C=O, and O-H. Antioxidant activity tests showed that within a certain concentration range, the higher the polysaccharide concentration, the stronger its radical scavenging abilities. Compared with Vitamin C(Vc), the polysaccharides had stronger scavenging abilities for DPPH· and OH·, some scavenging ability for ABTS+·, and Fe3+ reduction ability, and corresponding to IC50 values of 0.9625, 9.1909, and 235.69 mg/mL respectively. The Fe3+ reducing power reached a maximum absorbance of 0.38899 at a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL. T. molitor polysaccharides demonstrate promising antioxidant activity and potential as functional ingredients in food, health products, and pharmaceuticals, providing new technical references for the development and utilization of T. molitor resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a result of extreme climate change, which has led to a number of health disparities and problems, natural products containing bioactive compounds have gained attention for due to their health benefits1,2. The recent positive evaluation of edible crickets, Tenebrio molitor, and grasshoppers as novel food products by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) provides new opportunities for the development of functional foods3. T. molitor is a widely distributed edible insect globally, known for its short life cycle averaging around three month4, high reproduction rate, and favorable breeding conditions, which facilitate its relatively easy industrialization .

Polysaccharides are bioorganic macromolecules consisting of multiple monosaccharide molecules linked by α- or β-glycosidic bonds5,6. Polysaccharides can be categorized into plant polysaccharides, animal polysaccharides, microbial polysaccharides and artificial polysaccharides according to their sources3,7,8,9. Due to their diverse bioactivities, high safety, and low or no side effects, polysaccharides hold a crucial position in food, medicine, and biodegradable packaging materials. Consequently, developing bioactive polysaccharides has become a focus for many researchers8. Rui Guo et al.10 reviewed that yeast polysaccharides, Trametes versicolor polysaccharides, fucoidan, and sepia ink polysaccharides can serve as bioactive macromolecules for tumor prevention and treatment. Mingzhi Li et al.11 demonstrated that glucomannans derived from konjac, aloe vera gel polysaccharide, and Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide can modulate human immune responses and improve immune regulation. In recent years, research on T. molitor has shifted from studying the entire insect to focusing on its bioactive components such as peptides, flavonoids, and polysaccharides, due to the wide array of bioactive substances and resources available7.

Previous studies have demonstrated that T. molitor polysaccharides possess significant antioxidant properties, rendering them suitable for use in nutritional health foods. However, current extraction methods for T. molitor polysaccharides predominantly rely on traditional hydrothermal extraction, known for its inefficiency and lengthy extraction times. Therefore, developing a new, efficient extraction technique and elucidating its structural characteristics are crucial for the further development and utilization of T. molitor resources. Ultrasound-assisted extraction is widely recognized for its low-temperature, low-loss characteristics, effectively minimizing component loss in the extract and enhancing extraction efficiency12, and is frequently employed in the extraction of polysaccharides from animals and plants12,13,14,15. The vibration and cavitation effects of ultrasound enhance the capillary effect and accelerate the mass transfer process, thereby reducing energy consumption, carbon dioxide emissions, and solvent usage. This makes it an environmentally friendly and efficient physical treatment method14. Optimizing the extraction process of T. molitor polysaccharides through ultrasound-assisted extraction technology and further studying their antioxidant capacity and structural characteristics are expected to provide scientific evidence for their application as health products in the food and pharmaceutical fields.

Materials and methods

Materials

T. molitor was purchased from Aijia Pet Aquarium Supplies Co., Ltd.(Shanghai, China). 2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) was purchased from Shanghai McLean Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl was purchased from Shandong Xiya Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China). Ascorbic acid was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory. (Tianjin, China). All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Methods

Single-factor experiment for the extraction of T. Molitor polysaccharides

The treatment of Tenebrio molitor was based on the method proposed by Gkinali et al.16. In brief, Tenebrio molitor were crushed and treated with petroleum ether for degreasing (material-liquid ratio 1:8, 45 °C, 4 h) in a water bath. After static stratification, the supernatant was separated to recover the petroleum ether. The resulting dried powder of Tenebrio molitor was sieved (80 mesh) and saved.

1.0 g of defatted T. molitor powder was weighed put it into a conical flask with a certain amount of deionized water, and placed it in an ultrasonic processor (WKS900/3S, Jiangsu Jiangda Wukesong Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) with an ultrasonic frequency of 40 kHz. When examining a single factor, other conditions were fixed as follows: an ultrasonic power of 200 W, an ultrasonic time of 90 min, an ultrasonic temperature of 70 °C, and a liquid‒to-feed ratio of 20: 1 mL/g. The single-factor experimental conditions were 160, 200, 260, 300 and 360 W for ultrasonic power; 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 min for ultrasonic time; 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 25:1 and 30:1 mL/g for the liquid‒to-feed ratio; and extraction temperatures of 60 °C, 65 °C, 70 °C, 75 °C, and 80 °C. After ultrasonic treatment, the supernatant was removed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the polysaccharide content was determined.

Response surface experimental design for the extraction of T. Molitor polysaccharides

Based on the results of the single-factor experiments, three factors were selected: extraction temperature (A), extraction time (B), and ultrasonic power (C), with the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides as the response variable. A Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was employed for a three-factor, three-level experimental design. The response surface methodology was employed to optimize the extraction parameters for T. molitor polysaccharides. The selected factors and their levels were list in Table 1.

Determination of polysaccharides by the phenol sulfuric acid method

The determination of polysaccharides followed the method described by Tatsuya Masuko et al.17. Briefly, the sample reacts with phenol and concentrated sulfuric acid, resulting in a color change. The absorbance is measured at 490 nm to calculate the polysaccharide concentration. The polysaccharide yield is then calculated using the following formula:

X: concentration of T. molitor polysaccharides (mg/mL); V1: diluted solution after fixation (mL); V2: content of polysaccharide removed at the time of determination (mL); m: the mass of T. molitor powder (g).

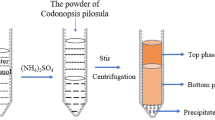

Polysaccharide purification

Three times the volume of 95% ethanol was added to the polysaccharide supernatant, and the mixture was left at 4 °C overnight. After centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was poured off, and a certain amount of water was added to the centrifuge tube to dissolve the precipitate. The dissolved solution was The dissolved solution was transferred to a graduated cylinder to measure its volume, and this volume was then poured into a clean conical flask. Then, twice the volume of the chloroform–n-pentanol reagent mixture (5:1)18 was measured and added to the conical flask containing the solution, The mixture was shaken well for 10 min, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, and then the intermediate protein layer and the bottom organic phase layer were removed. This process was repeated more than four times. The obtained supernatant was placed in a dialysis bag and dialyzed for 24 h. Finally, the dialyzed supernatant was freeze-dried to obtain the purified polysaccharide sample.

Infrared spectral analysis

A 3.0 mg polysaccharide sample mixed with 100 mg of KBr was weighed and placed in an onyx mortar to pulverize it into a fine powder, which was scanned in the wavelength range of 4000–500 cm− 1, and the spectral peaks were observed.

Determination of the antioxidant activity of T. Molitor Polysaccharides

Determination of DPPH radical scavenging activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined following the method described by Ilhami Gulcin and Saleh H. Alwasel19. For the determination of DPPH radical scavenging activity, DPPH was first dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 0.1 mM. Then, 2 mL of Polysaccharide extracts of different concentrations (0.2-1.8 mg/mL) was added to 3 mL of the DPPH solution. The reaction was carried out in the dark for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 517 nm using a UV-1900PC UV Dual-Beam Visible Spectrophotometer (UV-1900PC, Meixi Instruments Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China)). The DPPH scavenging activity was calculated using the following formula:

Where Asample, Ablank, and Acontrol represent the absorbance of the sample, blank, and control (DPPH without sample), respectively, measured at a wavelength of 517 nm.

Determination of hydroxyl (OH·) radical scavenging activity

The method of Homayouni-Tabrizi et al.20 was employed to assess hydroxyl radical scavenging activity with slight modifications. A mixture of phenanthroline (0.75 mM) and FeSO4 (0.75 mM) was prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After adding 0.01% H2O2 and different fractions, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Absorbance was finally measured at 536 nm wavelength. The scavenging activity of Hydroxy radicals in samples was evaluated using the following formula:

Where Asample represents the absorbance of the sample; A1 denotes the absorbance of the control group containing 1,10-phenanthroline, FeSO4, and H2O2; and A0 signifies the absorbance of the blank control group containing 1,10-phenanthroline and FeSO4.

Determination of reducing power

The determination of reducing power was referenced from the method of Fang Chen et al.21 with minor modifications. Briefly, various concentrations of polysaccharide solutions were taken into different test tubes, followed by sequential addition of 2.0 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide solution and 0.2 mol/L phosphate buffer solution. The reactions were carried out in a 50 °C water bath for 20 min, followed by cooling to room temperature. Subsequently, 2.0 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid solution was added, and the mixtures were left in the dark for 10 min. After centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min, 2.0 mL of the supernatant, 2.0 mL of distilled water, and 0.2 mL of 1% ferric chloride solution were gently mixed and the absorbance was measured at 710 nm wavelength.

Positive control: Vitamin C solution was used instead of the sample solution for measurement.

Blank control: Distilled water was used instead of the sample solution for measurement.

Determination of ABTS+ radical scavenging activity

The determination method was based on the method of Irina Georgiana Munteanu, Constantin Apetrei22 with slight modifications.

Briefly, equal volumes of ABTS solution (7.0 mmol/L) and potassium persulfate solution (2.5 mmol/L) were mixed thoroughly and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 16 h. The resulting solution was diluted with anhydrous ethanol to achieve an absorbance range of 0.7 ± 0.1 at a wavelength of 734 nm. Subsequently, 0.5 mL and 4.5 mL of various concentrations of polysaccharide solutions were separately mixed with ABTS solution and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 6 min. Absorbance values were measured at 734 nm and recorded as A1. Anhydrous ethanol was used in place of ABTS solution to measure the absorbance values, recorded as A2. Distilled water was used in place of the sample solution to measure the absorbance values, recorded as A0. The calculation formula is as follows:

Statistical analyses

All experiments were conducted with three replicates, and the results were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA was performed with a 95% confidence level. Polynomial model fitting and determination of optimal conditions were carried out using Design-Expert 8.0.

Results

Single-factor experiment for the extraction of T. Molitor polysaccharides

Effect of temperature on the polysaccharide yield of T. Molitor

As shown in Fig. 1(a), the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides exhibits a trend of initial increase followed by decrease with increasing temperature. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings of Chemat F et al.23 and Kumar K et al.23,24, indicating that temperature directly influences the properties of solutes and solvents (such as viscosity, vapor pressure, and surface tension), thereby affecting cavitation and its effects. With increasing temperature, the diffusivity of the solvent and pigment solubility23,25,26, resulting in higher polysaccharide yield. At 75 °C, the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides peaked at 10.15%, followed by a decrease. This decline may be attributed to reduced intermolecular forces among solvent molecules and increased vapor pressure at high temperatures, leading to more solvent vapor entering cavitation bubbles. The vapor inside the bubbles acts as a “cushioning effect” during cavitation, reducing the intensity of bubble collapse23,27,28 and thereby weakening the ultrasonic cavitation effect, A similar study was done by Zilong Dang et al.29. Therefore, 75 °C was chosen to continue the subsequent optimization experiments for ultrasound-assisted extraction of T. molitor polysaccharides.

Effect of time on the yield of T. Molitor polysaccharide

As shown in Fig. 1(b), according to the single-factor experimental design, the extraction temperature was set at 70 °C. With the extension of time, the polysaccharide yield of T. molitor tended to first increase and then decrease. At extraction times of 60, 90, 120, and 150 min, the polysaccharide yield of T. molitor gradually increased to 5.377%, 5.573%, 5.823%, and 8.350%, respectively, possibly due to the continuous dissolution of polysaccharide molecules from T. molitor powder. At 150 min, the polysaccharide yield was the highest, reaching 8.350%. Due to the mechanical damage caused by ultrasound to large molecules, the molecular structures of polysaccharides will be destroyed with the extension of ultrasound time, resulting in a decrease in polysaccharide yield with the extension of time30. A one-way ANOVA with P < 0.05 indicated that the effect of this factor was significant.Therefore, 150 min was chosen to continue the subsequent optimization experiments for ultrasound-assisted extraction of T. molitor polysaccharides.

Effect of the liquid-to-feed ratio on the yield of T. Molitor polysaccharides

As shown in Fig. 1(c), as the liquid-to-feed ratio increased, the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides tended to first increase and then decrease. The yield of T. molitor polysaccharides gradually increased when the liquid-to-feed ratio was 10:1 or 15:1, but when the liquid-to-feed ratio reached 15:1, the maximum yield reached 15.14%; this may be because the solute and solvent reached saturation, after which the yield gradually decreased, possibly because the solution had reached saturation; distilled water was then added, which only allowed other impurities to dissolve, hindering the dissolution of polysaccharides. Therefore, the yield gradually decreased31. A one-way ANOVA with P > 0.05 indicated that the effect of this factor was not significant. Therefore, it was determined that 15:1 is a suitable condition for ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides.

Effect of ultrasound power on the yield of T. Molitor polysaccharides

As shown in Fig. 1(d), the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides exhibits a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing with increasing ultrasound power. At an ultrasound power of 280 W, the extraction yield reaches a maximum of 10.45%. Subsequently, the polysaccharide yield decreases gradually with further increases in ultrasound power, consistent with findings reported by Gao et al.32, Zhang et al.33, and da Rocha and Noreña et al.34. This phenomenon is attributed to cavitation during ultrasound processing, which generates hydroxyl radicals (OH) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) free radicals, leading to compound degradation35. Similar reports were made by Fan Gu et al.36 and Xintian Hu et al.37. Consequently, the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides decreases accordingly. One-way ANOVA indicated that the factor had a significant effect with P < 0.05.

Analysis of the response surface experiment results

Establishment and analysis of a regression model for the yield of T. Molitor polysaccharides

In the response surface experiment, a quadratic model was employed. Based on the results of single-factor experiments, we examined extraction temperature, extraction time, and ultrasonic power as variables of interest, with the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides as the response value. Similar response surface experiments were also conducted by Liao Ningbo et al.38 and Adane Tilahun Getachew et al.39. Utilizing response surface analysis software, we derived the following regression equation:

Table 2 lists the 17 experimental setups generated by Design-Expert software and their corresponding outcomes, while Table 3 presents the results of the variance analysis. As shown in Table 3, the regression analysis of experimental data yielded a p-value of less than 0.001, indicating a significant regression model for T. molitor polysaccharides preparation. Factors C, A2, B2, C2, A, and AC in Table 3 all have p-values less than 0.05, with C, A2, B2, and C2 showing highly significant effects and A and AC showing significant effects, demonstrating the model’s applicability for optimizing polysaccharide extraction processes. Moreover, Table 3 reveals that power > temperature > time in terms of their impact on T. molitor polysaccharide yield.

Response surface analyses of the yield of T. Molitor polysaccharides

The impact of the interaction effect between two factors on the response surface results of T. molitor polysaccharides is illustrated in Fig. 2. As shown, all three response surface plots exhibit concave-downward surfaces, indicating the presence of peaks. The steeper the response surface curve, the more pronounced the effect of this factor on the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides. These findings suggest a significant interaction effect between the two factors on polysaccharide yield.

The curvature of the response surface reveals that, while the extraction temperature was held constant, variations in extraction time led to an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease in the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides, indicating a discernible trend. Conversely, when the extraction time was kept constant, the impact of the extraction temperature on the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides was a more pronounced trend, suggesting that the extraction temperature had a greater influence on the polysaccharides yield than the extraction time. Similarly, as depicted in Fig. 2(c), ultrasound power had a more substantial effect on the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides than did extraction time. Furthermore, Fig. 2(b) shows that the influence of ultrasound power on the polysaccharides yield surpassed that of the extraction temperature. These findings underscore the significant impact of extraction parameters, particularly extraction temperature and ultrasound power, on the yield of T. molitor polysaccharides.

Confirmation and Verification of the predictive model

Based on the results of the regression model analysis, the optimal extraction conditions for ultrasound-assisted extraction of T. molitor polysaccharide were determined as follows: an extraction temperature of 72.81 °C, an extraction time of 149.87 min, and an ultrasonication power of 266.97 W, resulting in a T. molitor polysaccharide yield of 9.411%. To validate the model, experiments were conducted under the following conditions: an extraction temperature of 73 °C, an extraction time of 150 min, an ultrasound power of 270 W, Under these adjusted conditions, three parallel experiments were conducted, yielding a T. molitor polysaccharides yield of 9.513%. The yield obtained under the refined experimental conditions closely aligned with the predicted yield from the model, validating the model’s utility for predicting conditions. Consequently, the forecasted conditions provided by this model are deemed reliable and applicable.

Infrared spectral analysis

The infrared spectrum analysis of purified polysaccharides from T. molitor is depicted in Fig. 3. The infrared spectra obtained using an infrared spectrometer revealed absorption peaks specific to polysaccharides, including peaks near 3416.08 cm− 1 attributed to O-H stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of O-H bonds in the samples40,41,42. The peak at 2928.08 cm− 1 indicates saturated C-H stretching vibrations, consistent with findings by Hu, W. et al.43 in their study on polysaccharides from Camptotheca acuminata fruits. Additionally, the peak at 1780.03 cm− 1 signifies C=O asymmetric stretching vibrations44. while the peak near 1442 cm− 1 corresponds to C-O stretching vibrations44,45. Furthermore, the three absorption peaks at 1097.41, 1048.35, and 1020.24 cm− 1 indicate the presence of pyranose structures27,46,47.

Analysis of the antioxidant activity of T. Molitor Polysaccharides

DPPH radical scavenging activity of T. molitor polysaccharides

As shown in Fig. 4(a), the scavenging capacity of T. molitor polysaccharides for DPPH radicals increased from 3.774 to 78.46% as the polysaccharide concentration increased from 0.2 mg/mL to 1.6 mg/mL. At a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL, Vc achieved a scavenging capacity of 83.04% for DPPH radicals, with an IC50 of 0.9625 mg/mL. These results indicate that T. molitor polysaccharides possess significant radical-scavenging activity.

Reducing Power of T. molitor Polysaccharides Toward Fe3+

As depicted in Fig. 4(b), the absorbance values increased with higher concentrations of both T. molitor polysaccharides and Vc, indicating a positive correlation between the reducing power towards ferric ions and the sample concentration. At the maximum concentration of 1.60 mg/mL, the mean absorbance value for the reducing power of T. molitor polysaccharides towards Fe3+ ions was 0.3517, compared to 2.638 for Vc. Although the reducing power of the polysaccharide solution was lower than that of Vc, it still demonstrated a significant capacity to reduce ferric ions.

OH· Radical Scavenging Activity of T. molitor Polysaccharides.

As illustrated in Fig. 4(c), as the concentration of T. molitor polysaccharides increased from 0.2 mg/mL to 1.6 mg/mL, the scavenging capacity for hydroxyl radicals increased from 11.58 to 36.56%. These results suggest that the ability of polysaccharides to scavenge hydroxyl radicals is directly proportional to their concentration. At a concentration of 1.60 mg/mL, Vc achieved a scavenging rate of 47.39% with an IC50 value of 9.1909 mg/mL. Although the hydroxyl radical-scavenging capacity of the T. molitor polysaccharides was lower than that of Vc, the polysaccharides still demonstrated significant scavenging activity.

ABTS+ Radical Scavenging Activity of T. molitor polysaccharides.

As shown in Fig. 4(d), as the concentration of T. molitor polysaccharides increased from 0.2 mg/mL to 1.6 mg/mL, their capacity to scavenge ABTS⁺ radicals rose from 5.198 to 16.05%. At a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL, Vc achieved a scavenging ability of 98.96% for ABTS+ radicals, with an IC50 of 235.69 mg/mL. Under these experimental conditions, T. molitor polysaccharides demonstrated a notable ability to scavenge ABTS⁺ radicals.

Discussion

This study utilized defatted T. molitor as the experimental material to investigate the optimal ultrasonic-assisted extraction conditions of polysaccharides, their antioxidant activities, and to preliminarily characterize their structure. Based on single-factor experiment results and response surface analysis, the optimal parameters for ultrasonic-assisted extraction of T. molitor polysaccharides were determined and validated: an extraction temperature of 73 °C, an extraction time of 150 min, an ultrasonic power of 270 W, and a liquid-to-feed ratio of 15:1 mL/g. Under these conditions, the polysaccharide yield was 9.513%. Wang et al.48 extracted selenopolysaccharide from Cordyceps sinensis SU-02 cells by ultrasound-assisted extraction with a yield of 11.52%. In a review of Cordyceps polysaccharides by QianghuaYuan et al.15 comparing hot water extraction, alkaline water extraction, and ultrasonic extraction, it was found that ultrasonic waves increased the cell rupture rate, enhanced solvent penetration, and had the highest extraction rate.

Infrared spectroscopy analysis indicated the presence of pyranose monosaccharides and functional groups characteristic of polysaccharides, such as C = O and C-H. The antioxidant activity was assessed through four indicators: DPPH·, OH·, ABTS+· radical scavenging abilities, and Fe3+ reducing power. The results showed strong scavenging abilities for DPPH· and OH· radicals, moderate ABTS+· radical scavenging, and Fe3+ reducing power, with IC50 values of 0.9625, 9.1909, and 235.69 mg/mL, respectively, suggesting that the extracted polysaccharides exhibited significant antioxidant properties, and a similar study was done by Yiwen Shao et al.37 The Fe3+ reducing power was highest at a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL. Within a certain concentration range, higher polysaccharide concentrations correlated with stronger radical scavenging abilities. Thus, polysaccharides obtained through ultrasound-assisted extraction represent a sustainable source with potential applications in various food and health products. However, the antioxidant activity assessment in this study relied primarily on in vitro experiments, and actual performance in vivo may vary. Furthermore, this study only employed deproteinization and dialysis to remove impurities from the extracted polysaccharides. Future research could focus on further purification of these polysaccharides and conduct in-depth structural analysis, as well as explore the relationship between structure and functional activity.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Smith, G. S., Anjum, E., Francis, C., Deanes, L. & Acey, C. Climate Change, Environmental disasters, and Health inequities: The underlying role of structural inequalities. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 9, 80–89 (2022).

Chaturvedi, S., Sachchan, T. K., Sharma, S. & Agarwal, A. Sustainable functional food system: Key to achieve sustainable development goal 3. In Bioactive Components: A Sustainable System for Good Health and Well-Being (ed. Thakur, M. & Belwal, T.) 571–583 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2023).

Khayrova, A., Lopatin, S. & Varlamov, V. Obtaining chitin, chitosan and their melanin complexes from insects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 167, 1319–1328 (2021).

Lee, J. H. et al. Changes in food composition of tenebrio molitor by life stage. Korean J. Food Cook. Sci. 32, 656–663 (2016).

Berends, S. E., Strik, A. S., Löwenberg, M., D’Haens, G. R. & Mathôt, R. A. A. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 58, 15–37 (2019).

Chassaing, B., Aitken, J. D., Malleshappa, M. & Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)‐induced colitis in mice. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 104 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Effect of ultrasonic degradation on the structural feature, physicochemical property and bioactivity of plant and microbial polysaccharides: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 236, 123924 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Regulation strategy, bioactivity, and physical property of plant and microbial polysaccharides based on molecular weight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 244, 125360 (2023).

Cooper, H. S., Murthy, S. N., Shah, R. S. & Sedergran, D. J. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab. Invest. 69, 238–249 (1993).

Guo, R. et al. Polysaccharides as potential anti-tumor Biomacromolecules -A Review. Front. Nutr. 9, 838179 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Innate immune receptors co-recognition of polysaccharides initiates multi-pathway synergistic immune response. Carbohydr. Polym. 305, 120533 (2023).

Garcia, J., Rodrigues, F., Saavedra, M. J., Nunes, F. M. & Marques, G. Bioactive polysaccharides from medicinal mushrooms: A review on their isolation, structural characteristics and antitumor activity. Food Biosci. 49 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Interactions between polysaccharides and gut microbiota: A metabolomic and microbial review. Food Res. Int. 160, 111653 (2022).

Khan, R., Shah, M. D., Shah, L., Lee, P. C. & Khan, I. Bacterial polysaccharides-A big source for prebiotics and therapeutics. Front. Nutr. 9, 1031935 (2022).

Yuan, Q. et al. Extraction, structure and pharmacological effects of the polysaccharides from Cordyceps sinensis: A review. J. Funct. Foods 89 (2022).

Gkinali, A. A., Matsakidou, A., Moschakis, T. & Paraskevopoulou, A. Egg-free mayonnaise-type emulsions stabilized with proteins derived from the larvae of Tenebrio molitor. Food Hydrocoll. 156, 110249 (2024).

Masuko, T. et al. Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol-sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 339, 69–72 (2005).

Li, H. et al. Purification, Structural characterization, and Antitumor Activity of a polysaccharide from Perilla Seeds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2023).

Gulcin, İ. & Alwasel, S. H. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes 11 (2023).

Homayouni-Tabrizi, M., Asoodeh, A. & Soltani, M. Cytotoxic and antioxidant capacity of camel milk peptides: effects of isolated peptide on superoxide dismutase and catalase gene expression. J. Food Drug Anal. 25, 567–575 (2017).

Chen, F., Huang, G., Yang, Z. & Hou, Y. Antioxidant activity of Momordica charantia polysaccharide and its derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 138, 673–680 (2019).

Munteanu, I. G. & Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021).

Chemat, F. et al. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 34, 540–560 (2017).

Kumar, K., Srivastav, S. & Sharanagat, V. S. Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) of bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable processing by-products: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 70, 105325 (2021).

Romero-Díez, R. et al. Microwave and ultrasound pre-treatments to enhance anthocyanins extraction from different wine lees. Food Chem. 272, 258–266 (2019).

Bruno Siewe, F., Kudre, T. G. & Narayan, B. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction conditions of umami compounds from fish by-products using the combination of fractional factorial design and central composite design. Food Chem. 334, 127498 (2021).

Lin, B., Wang, S., Zhou, A., Hu, Q. & Huang, G. Ultrasound-assisted enzyme extraction and properties of Shatian Pomelo peel polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 98, 106507 (2023).

Nadar, S. S., Rao, P. & Rathod, V. K. Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: A review. Food Res. Int. 108, 309–330 (2018).

Dang, Z. et al. Structure and antioxidant activity study of sulfated acetamido-polysaccharide from Radix Hedysari. Fitoterapia. 89, 20–32 (2013).

Nie, M. et al. Physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibility of highland barley starch with different extraction methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 303, 120458 (2023).

Umavathi, S. et al. Optimization of aqueous-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch) and their biological activities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 6692–6700 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Recovery of astaxanthin from shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) waste by ultrasonic-assisted extraction using ionic liquid-in-water microemulsions. Food Chem. 325, 126850 (2020).

Zhang, L., Fan, G., Khan, M. A., Yan, Z. & Beta, T. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction and identification of anthocyanin components from mulberry wine residues. Food Chem. 323, 126714 (2020).

Gerardi, C. et al. Strategies for reuse of skins separated from grape pomace as ingredient of functional beverages. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8 (2020).

Zafra-Rojas, Q. Y. et al. Effect of ultrasound on in vitro bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) residues cv. Tupy. Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 75, 608–613 (2020).

Gu, F. et al. Ultrasonic-Cellulase synergistic extraction of crude polysaccharides from Moringa oleifera leaves and alleviation of insulin resistance in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from coix seeds: Optimization, purification, and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 374, 131636 (2022).

Getachew, A. T., Lee, H. J., Cho, Y. J., Chae, S. J. & Chun, B. S. Optimization of polysaccharides extraction from Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) using subcritical water: Structural characterization and biological activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 121, 852–861 (2019).

Liao, N. et al. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction of polysaccharide from Corbicula fluminea: Characterization and antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 60, 1113–1121 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction and characterization of polysaccharides from dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) leaves. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 846–856 (2019).

Nie, C., Zhu, P., Ma, S., Wang, M. & Hu, Y. Purification, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from stem lettuce. Carbohydr. Polym. 188, 236–242 (2018).

Ge, Y., Duan, Y., Fang, G., Zhang, Y. & Wang, S. Polysaccharides from fruit calyx of Physalis alkekengi var. Francheti: Isolation, purification, structural features and antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 77, 188–193 (2009).

Hu, W. et al. Microwave-assisted extraction, physicochemical characterization and bioactivity of polysaccharides from Camptotheca acuminata fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 133, 127–136 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Preliminary characterization, antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of polysaccharides from Mallotus Furetianus. Carbohydr. Polym. 215, 307–315 (2019).

Pan, X. et al. Ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvents extraction of polysaccharides from Morchella Importuna: Optimization, physicochemical properties, and bioactivities. Front. Nutr. 9, 912014 (2022).

Fan, J. et al. Antioxidant activities of the polysaccharides of Chuanminshen Violaceum. Carbohydr. Polym. 157, 629–636 (2017).

Feng, H. & Tian, L. Study on extraction process of root of henry wood betony polysaccharides and their antitumor activity against S180. Molecules 26 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Extraction optimization and antioxidant activity of intracellular selenium polysaccharide by Cordyceps sinensis SU-02. Carbohydr. Polym. 86, 1745–1750 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Henan Provincial Health Commission. Project Number: LHGJ20210561. Project Title: Mechanistic study of 5-azacytidine in the treatment of psoriasis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributionsZH participated in the entire experimental manipulation, analyzing and interpreting the data.LX was involved in the direction of the experiments and made significant contributions to the writing of the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Li, X. & Zhang, H. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Tenebrio molitor. Sci Rep 14, 28526 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79482-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79482-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative evaluation of ultrasound-assisted extraction and micelle-mediated extraction of bioactive compound from Acmella oleracea

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Extraction process and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of total flavonoids from Broussonetia papyrifera leaves

Scientific Reports (2025)