Abstract

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a syndrome characterized by the acute decompensation of chronic liver disease, resulting in organ failure and high short-term mortality. The progression of ACLF is dynamic and reversible in a considerable proportion of patients during hospitalization. Early detection and accurate assessment of ACLF are essential; however, ideal methods for this purpose are still lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a new score for predicting the onset of ACLF in patients with various chronic liver diseases.A total of 6,188 patients with various chronic liver diseases were included in the study. Clinical and laboratory data were collected, and the occurrence of ACLF within 28 days was recorded. The Lasso-Cox regression method was employed to develop prediction models for the onset of ACLF at 7, 14, and 28 days. Among 5,221 patients without ACLF, 477 progressed to ACLF within 28 days. Seven predictors were identified as significantly associated with the occurrence of ACLF at 7, 14, and 28 days. A new scoring system was developed as follows: [NEUT ≥ 7, 109/L; 1 or 0] × 0.49 + [PLT < 100, 109/L; 1 or 0] × 0.44 + [TBIL ≥ 35, µmol/L; 1 or 0] × 0.05 + [HDL-C < 0.5, mmol/L; 1 or 0] × 1.04 – Ln[Hb, g/L] × 0.89 + [BUN > 7, mmol/L; 1 or 0] × 0.51 + Ln[INR] × 0.87 + 3.40. This new score demonstrated superior discrimination, with the C-indexes of 0.958, 0.944, and 0.938 at 7, 14, and 28 days, respectively, outperforming those of four other scores (CLIF-C-ACLF-Ds, MELD, MELD-Na, and CLIF-C-ADs score; all P < 0.001). Additionally, the new score improved in predictive accuracy, time-dependent receiver operating characteristics, probability density function evaluations, and calibration curves, making it highly predictive for the onset of ACLF at all time points. The optimal cut-off value of 9.6 effectively distinguished between high- and low-risk patients for ACLF onset. These findings were further validated in a separate cohort of patients. A new progressive score, based on seven predictors, has been developed to accurately forecast the occurrence of ACLF within 7, 14, and 28 days in patients with various chronic liver diseases. This tool may be utilized to identify high-risk patients, tailor follow-up management, and guide the escalation of care, prognostication, and transplant evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

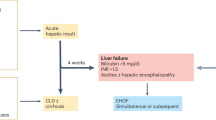

ACLF is a common and severe clinical syndrome characterized by acute decompensation (AD) in patients with chronic liver diseases. The primary manifestations include severe gastrointestinal symptoms, rapid worsening of jaundice, a tendency to bleed, and multiple organ failure, with a high short-term mortality rate ranging from 50–90%1,2.In recent years, various definitions and diagnostic criteria for the syndrome have been proposed by the major international scientific societies3. However, due to differences in etiology, underlying liver diseases, and study populations of ACLF across different countries and regions, the definitions, diagnostic criteria, clinical classifications, and prognostic assessments of ACLF vary and remain controversial. This variability creates confusion for clinicians in the diagnosis and treatment of the condition.

The factors that induce ACLF are complex and varied, and they can be classified into intrahepatic and extrahepatic categories based on their site of occurrence. Currently, the most common intrahepatic factors include chronic HBV reactivation, acute infections with the Hepatitis A virus (HAV) or Hepatitis E virus (HEV), alcoholism, hepatotoxic drugs, and ischemic hepatitis, among others. The most prevalent extrahepatic factors include bacterial infection, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and surgery. However, up to 40-50% of ACLF cases occur without identifiable predisposing factors.

The current management of ACLF focuses on supportive treatment for organ failures, primarily within an intensive care setting4. For selected patients, liver transplantation remains the only effective treatment that offers a favorable long-term prognosis. However, the high cost and the impact of post-transplant on patients’ physiology, psychology, and overall quality of life cannot be underestimated5,6.

ACLF is a highly dynamic syndrome characterized by reversibility. Most patients exhibit a clear prognosis between days 3 and 7 of hospital admission7. Therefore, early identification and accurate assessment of disease conditions are crucial for making clinical decisions regarding ACLF patients. The commonly utilized scoring systems include the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), CLIF-C Organ Failure Score (CLIF-C OFs), and CLIF-C ACLF score. While these scores demonstrate good performance in assessing ACLF prognosis and disease severity, their effectiveness in providing early warnings and accurate assessments of ACLF development for patients with various acute and chronic liver diseases remains unsatisfactory8,9,10,11,12.

In a retrospective study involving 75,922 patients with compensatory cirrhosis, Karen Y. et al13. used multivariate logistic regression to develop predictive models (called voice-Penn) for the occurrence of ACLF at 3, 6, and 12 months. They identified albumin (ALB), international normalized ratio (INR), total bilirubin (TBiL), and creatinine (Cr) as significant predictors at each time point. Additionally, hemoglobin emerged as a significant predictor at the 3- and 6-month time points, while age was a significant predictor in the 12-month model. However, the study population primarily consisted of male veterans with cirrhosis and a low prevalence of hepatitis B infection. In a prospective cohort study conducted in China involving hospitalized patients with hepatitis B infection and acute decompensation (AD), it was found that 33.7% of patients were diagnosed with ACLF14. Reactivation of chronic HBV infection has been reported as a significant and modifiable factor contributing to the development of ACLF4,15,16,17,18. Luo et al19. developed a novel prognostic score based on four predictors (ALT, TB, INR, and ferritin), which could accurately predict the onset of ACLF at 7, 14, and 28 days. However, it is important to note that the study exclusively included patients with HBV-related conditions, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other etiologies, such as alcoholic liver disease. Consequently, the study population lacks representativeness.

This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical characteristics of patients at high risk of ACLF and identified the risk factors contributing to its development. Building on these findings, a new ACLF risk prediction model was established using a large cohort of liver disease patients with diverse etiologies. Moreover, we embedded this model into an electronic medical record system to enable real-time monitoring and early warning of ACLF in patients with various chronic liver diseases, thereby facilitating the formulation of innovative management strategies to prevent disease progression and improve patient prognosis.

Patients and methods

Study Design

To identify patients at high risk for progression to ACLF, 6188 patients with various chronic liver diseases were recruited from the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine between 2018 and 2023. Detailed clinical data and outcomes for all enrolled subjects were collected at admission and throughout the 28-day observation period from the electronic data capture system and case report forms. These clinical data were subsequently analyzed to ascertain the characteristics associated with ACLF progression. Utilizing the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) analysis and Cox regression, a predictive score for the onset of ACLF was developed.

Patients and variable collection

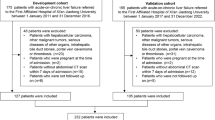

We initially screened and enrolled patients aged 18 to 80 years with chronic liver disease through the International Classification of Disease (ICD)-10 chronic liver disease codes. This included individuals with chronic liver disease in general as well as patients with chronic liver disease combined with acute complications of underlying diseases. Patients who underwent liver transplantation at the time of admission or lacked follow-up data during the 28-day observation period were excluded from the study. Additionally, we ruled out patients with baseline hepatocyte carcinoma or other malignancies, congestive heart failure, severe chronic kidney disease, pregnancy, those receiving immunosuppressive medications for other indications, or those with HIV infection. The patients were categorized into two groups: the ACLF group, which included those diagnosed with ACLF at baseline, and the non-ACLF group, which comprised patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for ACLF at baseline. Among the non-ACLF patients, those who progressed to ACLF within the 28-day observation period were classified as the developed ACLF group, while those who did not progress were labeled as the non-developed ACLF group. Throughout their hospitalization, all patients received integrated treatment. The diagnosis of ACLF was made according to the APASL ACLF criteria. We systematically gathered clinical data for each patient, including demographic information, comorbidities, complications, laboratory tests, and prognostic data. More detailed information about variables was provided in the Supplementary Methods section.

Modeling development and validation

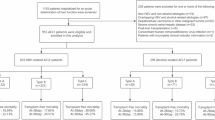

Datasets: All data were randomly divided into 80% derivation and 20% validation sets with no overlapping topics. This methodology guarantees the independence and integrity of the datasets, thereby facilitating accurate and reliable analysis.

Derivation datasets: 4,176 subjects were allocated to the training and testing datasets in a 9:1 ratio, including 3806 cases of non-developed ACLF and 370 cases of developed ACLF, further cross-validated 10 times to train model parameters.

Validation datasets:1,045 subjects including 938 non-developed ACLF cases and 107 developed ACLF cases were utilized to evaluate the performances of models.

Modeling approach and evaluation

The methodologies employed to identify the clinical characteristics of enrolled patients and to ascertain predictors associated with the occurrence of ACLF are described in the Supplementary Methods section. The identified predictors were utilized to formulate a novel scoring system for predicting the incidence of ACLF through multivariate Cox regression analysis19. The performance of this new score was evaluated in comparison to four established scoring systems (Chronic Liver Failure Consortium [CLIF-C] ACLF development score [CLIF-C ACLF-Ds]20, Model for End-stage Liver Disease score [MELDs]21, Model for End-stage Liver Disease-sodium score [MELD-Nas]21, CLIF Consortium Acute Decompensation score [ CLIF-C ADs]22) in predicting the onset of ACLF. This evaluation encompassed model discrimination, calibration, and overall performance23. Discrimination was assessed by the concordance index (C-index), time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC), and probability density function (PDF)24,25. Calibration was evaluated through calibration curves and goodness-of-fit using the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic test23,24. The overall performance was assessed using the R2 and Brier scales26, with superior performance indicated by a higher R2 value and a lower Brier scale score19. Detailed methodologies for discrimination using the C-index, calibration, and PDF analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods section.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were summarized in terms of counts and percentages. The cut-off value for the continuous variable was determined based on reference value ranges, ROC curves, and expert opinions. The analysis of continuous variables was conducted using the Two-Sample T-test and the Mann–Whitney U test, while the Chi-square test and the Fisher’s exact test were utilized for categorical variables. A paired T-test and McNemar test were used to compare repeated measurements of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The normality assumption was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and non-normal distributed data were transformed using natural logarithms. All statistical tests were two-sided with significance set at α less than 0·05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Version 19.0. The Python programming language (Python Sofware Foundation, version 3.6.6, https://www.python.org/downloads/) and R Version 4.3.2 (https://www.r-project.org) were utilized for model development. The libraries we used in Python included NumPy 1.23.5, Lifelines 0.27.8, Conda 23.5.0, Pandas 2.2.1, and Scikit-learn 1.2.1.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Result

Study populations

A total of 7,689 patients with various chronic liver diseases were initially screened in this study, of which 6,118 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included for analysis. According to the APASL-ACLF criteria, 897 patients were diagnosed with ACLF, while 5,221 patients were diagnosed with non-ACLF at enrollment (Fig. 1). The majority of the patients were male (3,999, 65.4%), with a median age of 59 years (interquartile range: 49 to 69). The median days of death was shorter in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group (32 days vs. 44 days). Short-term mortality rates at different time points (28, 90, and 365 days) were significantly higher in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group (18.8%/35.8%/45.9% vs. 2.5%/5.7%/7.4%, p < 0 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). Among the initial cohort of non-ACLF patients (n = 5,221), a total of 477 individuals progressed to ACLF within 28 days after enrollment. Patients who developed ACLF during follow-up were significantly older, with a median age difference of eight years compared to those who did not develop ACLF (66 years vs. 58 years; p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a notable increase in 28-day, 90-day, and 365-day mortality rates in the ACLF group compared to the non-ACLF group (18.4% vs. 0.9%, 36.6% vs. 2.5%, and 41.7% vs. 3.9%, respectively; P < 0 0.001) (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of patients at admission

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the non-ACLF, developed ACLF, and non-developed ACLF groups at admission. Among the non-ACLF patients, 35.4% had a history of cirrhosis. Notably, the prevalence of cirrhosis was significantly higher in the developed ACLF group compared to the non-developed ACLF group (61.2% vs. 32.9%, P < 0.001). In the cohort of patients with chronic liver disease, HBV infection was the most common etiology, followed by alcoholic liver disease. When comparing the developed ACLF group to the non-developed ACLF group, a higher incidence of alcoholic liver disease was observed in the former (13.8% vs. 5.0%, P < 0.001), alongside a lower incidence of HBV infection (23.1% vs. 71.6%, P < 0.001). A similar trend was also observed between the ACLF group and the non-ACLF group (alcoholic liver disease:18.7% vs. 5.8%, P < 0.001; HBV infection:32.0% vs. 67.2%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the incidence of cerebrovascular accidents was significantly higher in the developed ACLF group compared to the non-developed ACLF group (16.8% vs. 8.8%, P < 0.001). The occurrence of complications also varied significantly between the two groups. In the developed ACLF group, the predominant complications included bacterial infection (85.7%) and gastrointestinal hemorrhage (27.3%), followed by ascites (25.2%) and hepatic encephalopathy (20.1%). In the non-developed ACLF group, the primary complications were bacterial infection (35.1%) and ascites (11.7%), with gastrointestinal hemorrhage and hepatic encephalopathy reported in only 8.0% and 5.1% of patients, respectively.

At baseline, the developed ACLF group demonstrated significantly worse laboratory indicators compared with the non-developed ACLF group. Specifically, platelet count (PLT), hemoglobin, total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were all significantly lower than the reference values and those observed in the non-developed ACLF group (P < 0.001). Conversely, neutrophil ratio (NUET%), TBiL, direct bilirubin (DBiL), total bile acid (TBA), C-reactive protein (CRP), prothrombin time (PT), AST/ALT, international normalized ratio (INR), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were significantly elevated compared to non-developed ACLF (P < 0.001). For example, 73.2% and 70.2% of developed ACLF patients exhibited thrombocytopenia (median:61.0; interquartile range:34.00-103.00) and moderate anemia (median:78.0; Interquartile range:67.00–93.00), respectively. Additionally, CRP and NUET% were significantly elevated with medians of 45 mg/L and 82.1%, respectively, in the developed ACLF group, indicating a higher degree of systemic inflammation. When compared to normal reference values, the liver function index of median TBiL increased by 3.9-fold (interquartile range: 32.1-126.4) and DBiL increased by 5.6-fold (interquartile range:16.2–82.7). Furthermore, median plasma bile acids were continuously elevated, reaching up to 13.8-fold (interquartile range: 60.0-375.0). These findings indicated significant impairment of liver function and potential cholestasis (Table 1).

Furthermore, we contrasted the organ failures among various groups. In the ACLF group, the most prevalent failing organ systems were the liver (42.4%) and the respiratory system (35.1%), followed closely by coagulation (22.4%) and the circulatory system (19.4%) (Supplementary Table 1). In the developed ACLF group, the predominant organ failures were respiratory (53.2%) and circulatory (41.1%), with liver (16.1%) and kidney (10.7%) failures occurring less frequently. In contrast, the non-developed ACLF group exhibited a significantly lower incidence of organ failures, with respiratory failure accounting for only 10.6%, and markedly fewer cases of other organ failures compared to the aforementioned groups (Table 1).

Changes in clinical features during ACLF progression

To observe the clinical changes that occur in patients during the progression of ACLF, we compared the clinical characteristics of the developed group at both enrollment and onset. Initially, it was found that the average duration for non-ACLF advancement to progress to ACLF was approximately 7 days (interquartile range: 3–15 days). Furthermore, the deterioration of various intrahepatic and extrahepatic systems including liver damage, coagulation dysfunction, renal failure, and hematological disorders subtly indicated the evolving disease course associated with ACLF development. Laboratory indicators such as AST, TBiL, DBiL, PT, NLR, and BUN all markedly increased and the proportion of patients with a PLT of less than 30 rose from 20.3% to 26.5% as the disease progressed. Finally, there was a statistically significant increase in the incidence of both liver failure and coagulation failure, which escalated from 16.1% and 1.9%, to 29.8% and 9.0%, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Risk factors for ACLF development

In the modeling process, we screened the predictors in three steps. Initially, independent predictors associated with the development of ACLF were screened through univariate Cox proportional hazards regression (p < 0.05, HR > 1.0 or < 0.9; Supplementary Table 3). After eliminating redundant indicators based on the suggestions of clinical experts, a total of 38 variables were selected for lasso regression screening (Supplementary Fig. 1). This analysis identified 11 significant factors (HDL-C (< 0.5, mmol/L), NEUT (≥ 7,109 /L), TBiL (≥ 35, µmol/L), PLT(< 100, 109 /L), BUN (> 7, mmol/L), AST(> 40, U/L), ln (INR), ln(HGB), liver failure, bacterial infection, respiratory failure). Collinearity diagnostics confirmed the absence of multicollinearity among these variables (Supplementary Tables 4 − 1 and Supplementary Tables 4 − 2). Subsequently, these 11 indices were incorporated into a multivariate Cox regression analysis to further refine the selection of predictor. The findings indicated that except for AST (> 40, U/L), the remaining 10 factors were significantly associated with the progression of ACLF (Supplementary Table 5). However, considering both clinical relevance among variables and the early accessibility and quantifiability of clinical data, we excluded three indices (bacterial infection, respiratory failure, and liver failure), ultimately retaining seven variables for inclusion in the model: HDL-C, TBiL, INR, BUN, NUET, PLT, and HGB. The results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis for these seven predictors were as follow: (HDL-C (< 0.5, mmol/L) (hazard ratio [HR] 2.82; 95% CI 2.3–3.45; p < 0.005), TBiL (≥ 35, µmol/L) (HR 2.48; 95% CI 2.08–2.96; p < 0.005), ln(INR) (HR 2.4; 95% CI 1.75–3.3; p < 0.005), NEUT (≥ 7,109 /L) (HR 1.63; 95% CI 1.37–1.94; p < 0.005), PLT (< 100, 109 /L) (HR 1.55; 95% CI 1.32–1.82; p < 0.005), BUN (> 7, mmol/L) (HR 1.68; 95% CI 1.44–1.97; p < 0.005), and ln(HGB) (HR 0.41; 95% CI 0.31–0.54; p < 0.005) (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, collinearity diagnosis analysis confirmed that the effects of these 7 factors on ACLF development were independent of one another (Supplementary Table 6).

Developing a model to predict the onset of ACLF

Using a multivariate Cox regression approach, a model incorporating seven predictors ((HDL-C (< 0.5, mmol/L), TBiL(≥ 35, µmol/L), ln(INR), NEUT(≥ 7,109 /L), PLT(< 100, 109 /L), BUN (> 7, mmol/L) and ln(HGB) ) was established to predict the onset of ACLF at 7 /14/28 days. Their coefficients were utilized as relative weights to compute the corresponding score. The formula for calculating the prediction score is as follows: score=[NEUT ≥ 7,109/L;1 or 0]×0.49 + [PLT < 100,109/L;1 or 0]×0.44 + [TBIL≥ 35,µmol/L;1 or 0]×0.05 +[HDL-C < 0.5,mmol/L;1 or 0]×1.04 - Ln[Hb, g/L]×0.89 + [BUN > 7,mmol/L;1 or 0]×0.51 + Ln[INR]×0.87 + 3.40. The probability of ACLF onset can be estimated by the equation P = 1 - S(t) = 1 - exp(λ0(t) × exp (VE-ACLF-Dev)). λ0 was the cumulative baseline hazard and the score coefficient estimated by the model fitted for time t. λ0(7) = 0.0373, λ0(14) = 0.0817, λ0(28) = 0.4070.

Performance of the new prognostic score

In comparison to the CLIF-C-ACLF-Ds, MELD, MELD-Na, and CLIF-C-ADs scores, the VE-ACLF-Dev achieved high discriminative performance, as evidenced by the C-index, ROC curve, and probability density function analyses. The C-index values for the VE-ACLF-Dev were the highest (0.958/0.944/0.938) for predicting the onset of ACLF at 7/14/28 days (CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, 0.870/0.855/0.850; MELDs, 0.884/0.866/0.859; MELD-Na,0.858/0.835/0.827; CLIF-C-ADs,0.627/0.623/0.622) (Supplementary Table 7). Furthermore, our new score’s prediction error rates were significantly lower than those of the four other scores (CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, 67.7%/ 61.0%/58.5%; MELDs, 63.8%/57.9%/55.7%; MELD-Nas,70.5%/65.9%/63.9%; CLIF-C-ADs, 88.7%/85.1%/83.5%) (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Additionally, the time-dependent ROC analysis indicated that the VE-ACLF-Dev achieved the largest area under the ROC curves (0.968/0.949/0.934) compared to the four other scores at 7/14/28 days (Fig. 2). The sensitivity and specificity of the VE-ACLF-Dev were equal to 0.929/0.857/0.905, and 0.911/0.894/0.831 at different time points, respectively, which were higher than those of the four other scores (Supplementary Table 8).

Time-dependent ROC curves of the new and five other scores in the derivation and validation groups. (A) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting the development of ACLF at 7-day,14-day, and 28-day in derivation cohort; (B) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for predicting the development of ACLF at 7-day, 14-day, and 28-day in validation cohort; (C)time-dependent ROC curves of 28 day since admission in the derivation group; (D)time-dependent ROC curves of 28 day since admission in the validation group; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; AUROC, area under the ROC curve; ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; VE-ACLF-Dev, Various Etiologies ACLF Development Prediction; CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, Chronic Liver Failure Consortium acute-on-chronic liver failure development score; MELDs, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score; MELD-Nas, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium score; CLIF-C-ADs, CLIF Consortium Acute Decompensation score.

The results of PDF analysis revealed that the number of patients with developed ACLF increased as scores rose, and an obvious distinction was observed between the peaks of patients with developed ACLF and those without. The overlapping coefficients of VE-ACLF-Dev (13.7%/ 23.7%/29.7%) significantly decreased compared to the four other scores (CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, 31.7%/37.9%/40.6%; MELDs, 32.8%/42.3%/47.4%; MELD-Nas, 35.6%/47.5%/55.1%; and CLIF-C-ADs, 74.6%/75.3%/74.1%, all P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). The overall performance and calibration of VE-ACLF-Dev were also excellent at each time point. The calibration plot demonstrated a strong agreement between the predicted and actual probability of the onset of ACLF at 7/14/28 days (Hosmer–LemeshowX2 = 402.12/150.38/495.56, all P > 0.05, Brier: 0.04/0.06/0.13) (Fig. 4). Considering that the development of all CLIF-C scores was based on cohorts of cirrhosis, we evaluated the performance of the predictive score in cirrhosis and non-cirrhotic patients by the ROC curves. The results showed that the model could well predict the occurrence of ACLF at different time points in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients, with the AUC of 0.93/0.91/0.87 and 0.98/0.97/0.96 respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The probability density function of VE-ACLF-Dev for predicting 7-/14-/28-day ACLF onset in the derivation group. *P < 0.05 (Student t-test) for comparisons of the overlapping coefficient between the VE-ACLF-Dev and the other scores.#P < 0 0.001 (Mann–Whitney U test) for comparisons of scores between developed ACLF and non-developed ACLF patients. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; VE-ACLF-Dev, Various Etiologies ACLF Development Prediction; CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, Chronic Liver Failure Consortium acute-on-chronic liver failure development score; MELDs, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score; MELD-Nas, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium score; CLIF-C-ADs, CLIF Consortium Acute Decompensation score.

Risk stratification of the new score

By X-tile plot analysis of the VE-ACLF-Dev, the risk of ACLF onset at 7/14/28 days could be categorized into two strata: high risk (≥ 9.6) and low risk (< 9.6). The incidence of ACLF between the two groups on 7/14/28 days was significantly different (high-risk: 60.8%/68.4%/71.8%, low-risk: 1.9%/3.5%/5.9%, P < 0.001). We further calculated the hazard ratio of ACLF development in both groups. Compared with the low-risk group, the hazard ratios in the high-risk group were 36.42/23.34/18.64 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Risk stratification of Various Etiologies ACLF Development Prediction (VE-ACLF-Dev).

(A) Cumulative incidence of progression to ACLF at 7/14/28 days stratified according to the VE-ACLF-Dev classification rule (high/low risk: VE-ACLF-Dev 9.6/<9.6) in the derivation group. P < 0.001 (log-rank test) for comparison of the cumulative incidence. (B) Cumulative incidence of progression in the validation group. HR, hazard ratio.

Validation of the VE-ACLF-Dev prediction model

Out of 1,045 patients without ACLF in the validation group, 107 developed ACLF during hospitalization. The derivation and validation groups exhibited similar rates and outcomes of ACLF, as well as comparable clinical characteristics(Supplementary Table 9).In the validation group, the C-indexes of the model for predicting the onset of ACLF at 7/14/28 days all exceeded 0.90 (0.948/0.922/0.908) and significantly outperformed four other generic scores (CLIF-C ACLF-Ds,0.833/0.818/0.807, P < 0.001; MELDs, 0.863/0.843/ 0.830, P < 0.001; MELD-Nas, 0.820/0.801/0.785, P < 0.001; and CLIF-C-ADs, 0.552/0.563/0.562, P < 0 0.001)(Supplementary Table 7). Additionally, the prediction error rates of the new score for 7/14/28 day ACLF onset were considerably lower than those of the four other scores (CLIF-C ACLF-Ds, 69.2%/57.44%/52.16%; MELDs, 62.39%/50.53%/45.67%; MELD-Nas,71.32%/61.05%/57.01%; CLIF-C- ADs,88.5%/82.23%/78.96%) (Supplementary Fig. 4B). The time-dependent ROC analysis demonstrated that VE-ACLF-Dev exhibited the highest AUC values of 0.961, 0.939, and 0.912 at 7, 14, and 28 days, respectively, when compared to the four other scoring systems (Fig. 2). In Supplementary Table 8, we indicated that the sensitivity and specificity of the VE-ACLF-Dev were equal to 0.960/0.880/0.850, and 0.878/0.843/0.825 at different time points, respectively.

The PDF analysis revealed decreased overlapping coefficients of the new score between patients who developed ACLF and those who did not in the validation group (VE-ACLF-Dev: 15.0%/27.4%/35.4%; CLIF-C ACLF-Ds: 36.4%/41.2%/46.8%; MELDs: 31.9%/39.8%/46.6%; MELD-Nas: 37.5%/44.0%/52.8%; CLIF-C-ADs: 85.2%/81.3%/78.5%; all P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The calibration curve analysis showed a good agreement between the predicted and actual probabilities in the validation group (Hosmer–Lemeshow X² = 119.73/24.25/109.82; all P > 0.05; Brier: 0.04/0.07/0.15) (Fig. 4). The hazard ratios for ACLF onset at 7/14/28 days in the high-risk group (19.6/15.5/10.6, P < 0.001) were comparable to those in the derivation group when compared with the low-risk group and demonstrated similar separation efficiency in the validation group (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these results indicate that the VE-ACLF-Dev prediction model for predicting ACLF occurrence is statistically robust.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively compared the clinical characteristics of patients with developed ACLF and those without ACLF and identified ten independent factors most relevant to ACLF progression, including bacterial infection, liver failure, respiratory failure, and clinical indicators such as HDL-c, TB, INR, NEUT, PLT, BUN, and HGB. Previous studies have indicated that bacterial infection is not only the most prevalent extrahepatic precipitant for the development of ACLF but also a significant cause of short-term high mortality in ACLF patients, with remarkably higher rates compared to other causes of liver damage18,27,28,29,30,31. Our study further confirmed that bacterial infection is the only extrahepatic trigger associated with the progression to ACLF, reinforcing its central role in ACLF precipitating events. In addition to these precipitating factors, our study identified systemic inflammation as a contributing factor to the progression of ACLF, with neutrophil count (NEUT) identified as an independent risk factor. Numerous studies have reported elevated NEUT levels in ACLF patients compared to healthy controls, possibly due to increased levels of circulating granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)32. Moreover, neutrophil dysfunction is clinically significant, as impaired respiratory burst and phagocytic activity are associated with a higher risk of infection, organ failure, and mortality33,34.

Organ failure is a hallmark of ACLF and can manifest as renal failure, now commonly referred to as Acute Kidney Injury (AKI), as well as respiratory and circulatory failure35. A reversible acute increase in BUN is a classical biomarker for AKI and is considered a strong predictor of poor survival outcomes in both the short and long term for patients with ACLF36,37,38. Our research demonstrates that BUN levels in patients with developed ACLF are significantly elevated compared to those with non-developed ACLF, suggesting that BUN could serve as an early warning indicator for ACLF. Additionally, our findings indicate that the prevalence of liver failure and respiratory failure is higher in the developed ACLF group.

Our study showed that platelet levels were lower in patients with developed ACLF, aligning with previous research findings. Up to 75% of patients with advanced liver disease or cirrhosis experience thrombocytopenia, and its severity is typically directly correlated with the degree of liver failure. Studies have shown that platelet levels are an independent prognostic factor in ACLF patients, with depletion or redistribution responsible for thrombocytopenia40,41,42. Furthermore, we observed that patients in the developed ACLF group suffered from moderate anemia. Several studies have reported anemia as a common complication in ACLF patients, with various contributing factors identified, such as autoimmune disorders, decreased hematopoietic capability, and the release of tumor necrosis factor, cytokines, and endotoxins35,43. Another study by Cheng et al. also found that accelerated suicidal cell death or apoptosis could also contribute to anemia in patients with HBV-ACLF44.

Patients with liver failure often experience decreased liver synthesis and metabolic dysfunction, as well as coagulation dysfunction, which can lead to malnutrition and chronic occult bleeding. The presence of severe anemia in these patients results in decreased levels of hemoglobin and platelets. In ACLF patients, bilirubin was reported to trigger anemia by inducing erythrocyte death45,46. Moreover, it has been found that hemoglobin could not only identify individuals at high risk of developing ACLF but also serve as a strong predictor in the survival rates of patients with cirrhosis47, making it a potential target for ACLF prevention. Other predictive variables, such as TB and INR, which are well-established indicators of liver and coagulation dysfunction/failure, have been extensively utilized in various diagnostic criteria and prognostic scores for patients with ACLF. During the development and progression of ACLF, hepatocytes undergo varying degrees of degeneration and necrosis, which results in the disorder of coagulation factor synthesis. This disruption is manifested as prolonged coagulation time and elevated bilirubin levels, both of which are important indicators of liver reserve function. Low levels of HDL-C are commonly observed in patients with chronic liver disease and are inversely correlated with disease severity48. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in addition to predicting poor outcomes in HBV-ACLF patients, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels also played a significant role in the pathophysiology of systemic inflammation that precipitates the onset of ACLF49,50. Consistent with these findings, our study also revealed that HDL-C < 0.5 mmol/L is a strong predictor for ACLF progression.

ACLF is a life-threatening clinical syndrome characterized by high short-term mortality7. Despite liver transplantation being considered the most effective treatment for ACLF, its widespread implementation is hindered by the limited availability of donor organs and the high costs of the procedure51,52. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that ACLF is a dynamic syndrome that can be reversible in a significant proportion of patients4. This characteristic is closely related to the improved prognosis, highlighting the importance of dynamic assessment in the management of ACLF. A recent PREDICT study identified that pre-ACLF patients could develop ACLF within 3-months, exhibiting a mortality rate of 53.7% at three months and 67.4% at one year20. Under such circumstances, both early diagnosis of ACLF and accurate prediction of prognosis are essential for distinguishing patients who require transplantation from those who can survive with intensive medical care alone. In our study, we observed that approximately 9.13% (477/5221) of non-ACLF patients developed ACLF during hospitalization within 28 days. Among these patients, 51.8% (247/477) progressed within 7 days and 72.7% (347/477) progressed within 14 days, as determined by the APASL-ACLF criteria. These findings further emphasize the importance of predicting the onset of ACLF at different periods after admission and may facilitate timely interventions to prevent progression.

Thus, utilizing the framework of trigger factors-systemic inflammation-organ dysfunction/failure, we have developed a concise and accurate score to predict the progression of ACLF. In comparison with the other four established scores (MELD, MELD-Na, CLIF-C-ADs, and CLIF-C-ACLF-Ds), our model demonstrated superior discriminability and overall performance. While MELD, MELD-Na, and CLIF-C-ADs have been extensively used to predict the mortality and prognosis in patients with various severe liver diseases, exhibiting strong predictive value, their sensitivity and accuracy in forecasting ACLF development are comparatively lower8,10. Although the CLIF-C ACLF-Ds was specifically designed to predict ACLF occurrence in the AD population within 3 months, findings from the PREDICT study indicate that it does not exhibit greater accuracy than traditional clinical scores20. Our score could effectively screen high-risk patients prone to developing ACLF, thereby providing valuable clinical guidance for managing and treating patients with chronic liver disease.

Significant differences in the definition of ACLF between Eastern and Western countries have led to variations in the potential etiology, precipitating events, and prognosis of ACLF across different regions53. Consequently, recent years have witnessed a surge in research efforts devoted to developing diagnostic criteria and prognostic models specifically for single-etiology ACLF. For example, the COSSH study conducted in China has provided a valuable exploration of the diagnostic criteria and prognosis of HBV-ACLF24. However, there remains a clinical necessity for a progression model capable of identifying high-risk ACLF populations among patients with different etiologies and stages of chronic liver diseases. In this study, this study incorporates various etiologies and the state of chronic liver disease into the new model, which significantly expands the clinical applicability of the model.

Limitations

Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. Firstly, the retrospective nature of this study introduces the potential for selection bias. Nonetheless, the large sample size, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, and minimal data loss have contributed to reducing the likelihood of bias. Secondly, previous studies have reported that HBV reactivation and superimposed infection on HBV are significant contributors to ACLF18,54. However, due to the absence of dynamic HBV-DNA and HBV coinfection data, the impact of viral response and multiple infections of HBV on ACLF development could not be investigated in this study. Thirdly, since our data mainly came from the Yiwu area, future research should aim to externally validate our models in other cohorts from different regions.

Conclusion

In summary, early detection of patients at high risk of progression to ACLF is crucial for reducing both the prevalence and fatality rates associated with this condition. Our newly developed predictive model is applicable to a diverse range of patients with chronic liver disease and demonstrates superior performance compared to the MELD, MELD-Na, CLIF-C-ADs, and CLIF-C-ACLF-Ds scores. This model can aid in mitigating risk factors, identifying high-risk patients, and customizing follow-up management, which is essential for improving patient outcomes and reducing the burden of ACLF.

In our future work, we plan to conduct multicenter experiments to further validate our model across various datasets and real-world clinical scenarios, thereby fully establishing its effectiveness and utility. Additionally, we intend to incorporate more viral DNA and treatment data to enable real-time predictions of ACLF occurrence and prognosis for patients undergoing different clinical treatments. We believe that these efforts will facilitate the exploration of new clinical therapies, such as bioartificial liver support and stem cell transplantation, ultimately improving the survival rates and quality of life for ACLF patients.

References

Wu, T. et al. Development of diagnostic criteria and a prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gut. 67, 2181–2191. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314641 (2018).

Ngu, N. L. Y., Flanagan, E., Bell, S. & Le, S. T. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: controversies and consensus. World J. Gastroenterol. 29, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i2.232 (2023).

Sarin, S. K. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol. Int. 13, 353–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09946-3 (2019).

Kumar, R., Mehta, G. & Jalan, R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin. Med. (Lond). 20, 501–504. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0631 (2020).

Li, X., Zhang, L., Pu, C. & Tang, S. Liver transplantation in Acute-on-chronic liver failure: timing of transplantation and selection of patient population. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 1030336. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1030336 (2022).

Schulz, M. S., Gu, W., Schnitzbauer, A. A. & Trebicka, J. Liver transplantation as a cornerstone treatment for Acute-On-Chronic Liver failure. Transpl. Int. 35, 10108. https://doi.org/10.3389/ti.2022.10108 (2022).

Hernaez, R., Sola, E., Moreau, R. & Gines, P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut. 66, 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312670 (2017).

Blasco-Algora, S., Masegosa-Ataz, J., Gutierrez-Garcia, M. L., Alonso-Lopez, S. & Fernandez-Rodriguez, C. M. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Pathogenesis, prognostic factors and management. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 12125–12140. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12125 (2015).

Rashed, E., Soldera, J. CLIF-SOFA CLIF-C scores for the prognostication of acute-on-chronic liver failure and acute decompensation of cirrhosis: a systematic review. World J. Hepatol. 14, 2025–2043. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i12.2025 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Nie, Y., Liu, L. & Zhu, X. Assessing the prognostic scores for the prediction of the mortality of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure: a retrospective study. PeerJ. 8, e9857. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9857 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. A new dyslipidemia-based scoring model to predict transplant-free survival in patients with hepatitis E-triggered acute-on-chronic liver failure. Lipids Health Dis. 22, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01826-y (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Noninvasive models for predicting poor prognosis of chronic HBV infection patients precipitating acute HEV infection. Sci. Rep. 10, 2753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59670-4 (2020).

Xiao, K. Y. et al. Models for acute on chronic liver failure development and mortality in a veterans affairs cohort. Hepatol. Int. 14, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10060-y (2020).

Li, H. et al. Characteristics, diagnosis and prognosis of Acute-on-chronic liver failure in Cirrhosis Associated to Hepatitis B. Sci. Rep. 6, 25487. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25487 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation increased the risk of developing hepatic failure and mortality in cirrhosis with Acute Exacerbation. Front. Microbiol. 13, 910549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.910549 (2022).

Lei, J. H., Peng, F., Chen, Z. & Xiao, X. Q. Is HBV viral load at admission associated with the development of acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with acute decompensation of chronic hepatitis B related cirrhosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 363. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3988-1 (2019).

Yao, N., He, Y., Wu, Y., Wang, F. & Tian, Z. Prognostic value of plasma level of superoxide dismutase in HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. BMC Gastroenterol. 22, 312. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02371-1 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Role of precipitants in the transition of acute decompensation to acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with HBV-related cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 4, 100529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100529 (2022).

Luo, J. et al. Predicting the Onset of Hepatitis B Virus-related Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 681–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.016 (2023).

Trebicka, J. et al. The PREDICT study uncovers three clinical courses of acutely decompensated cirrhosis that have distinct pathophysiology. J. Hepatol. 73, 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.013 (2020).

Mahmud, N., Hubbard, R. A., Kaplan, D. E., Taddei, T. H. & Goldberg, D. S. Risk prediction scores for acute on chronic liver failure development and mortality. Liver Int. 40, 1159–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14328 (2020).

Jalan, R. et al. The CLIF Consortium Acute Decompensation score (CLIF-C ADs) for prognosis of hospitalized cirrhotic patients without acute-on-chronic liver failure. J. Hepatol. 62, 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.012 (2015).

Alba, A. C. et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users’ guides to the Medical Literature. JAMA. 318, 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.12126 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Development and validation of a new prognostic score for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J. Hepatol. 75, 1104–1115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.026 (2021).

Kang, L., Chen, W., Petrick, N. A. & Gallas, B. D. Comparing two correlated C indices with right-censored survival outcome: a one-shot nonparametric approach. Stat. Med. 34, 685–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6370 (2015).

Steyerberg, E. W. et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 21, 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 (2010).

Fernandez, J. et al. Bacterial and fungal infections in acute-on-chronic liver failure: prevalence, characteristics, and impact on prognosis. Gut. 67, 1870–1880. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314240 (2018).

Wong, F. et al. Clinical features and evolution of bacterial infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. J. Hepatol. 74, 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.046 (2021).

Van der Merwe, S., Chokshi, S., Bernsmeier, C. & Albillos, A. The multifactorial mechanisms of bacterial infection in decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 75 (Suppl 1), S82–S100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.029 (2021).

Zanetto, A. et al. Severity of systemic inflammation is the main predictor of ACLF and bleeding in individuals with acutely decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 78, 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.09.005 (2023).

Mucke, M. M. et al. Bacterial infection-triggered acute-on-chronic liver failure is associated with increased mortality. Liver Int. 38, 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13568 (2018).

Casulleras, M., Zhang, I. W., Lopez-Vicario, C., Claria, J. Leukocytes, Systemic inflammation and immunopathology in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Cells 9(12), 2632. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9122632 (2020).

Mookerjee, R. P. et al. Neutrophil dysfunction in alcoholic hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis is reversible and predicts the outcome. Hepatology. 46, 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21737 (2007).

Taylor, N. J. et al. The severity of circulating neutrophil dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis is associated with 90-day and 1-year mortality. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12886 (2014).

Piano, S. et al. Incidence, predictors and outcomes of acute-on-chronic liver failure in outpatients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 67, 1177–1184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.008 (2017).

Weil, D. et al. Prognosis of cirrhotic patients admitted to intensive care unit: a meta-analysis. Ann. Intensive Care. 7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-017-0249-6 (2017).

Belcher, J. M. et al. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 57, 753–762. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25735 (2013).

Wong, F. et al. A new consensus definition of acute kidney injury accurately predicts 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and infection. Gastroenterology 145, 1280–1288 e1281, doi: (2013). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.051

Scharf, R. E. Thrombocytopenia and hemostatic changes in Acute and Chronic Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Clinical and Laboratory features, and Management. J. Clin. Med. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071530 (2021).

Peng, H. et al. A prognostic model of acute-on-chronic liver failure based on Sarcopenia. Hepatol. Int. 16, 964–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-022-10363-2 (2022).

Xia, Q. et al. A modified MELD model for Chinese pre-ACLF and ACLF patients and it reveals poor prognosis in pre-ACLF patients. PLoS One. 8, e64379. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064379 (2013).

Ye, Q. X. et al. Short-term prognostic factors for hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. World J. Clin. Cases. 10, 8186–8195. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i23.8186 (2022).

Scheiner, B. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for anemia in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 40, 194–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14229 (2020).

Mei, C. et al. Increased suicidal erythrocyte death in patients with hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 323, G9–G20. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2020 (2022).

Khan, N. M. & Poduval, T. B. Bilirubin augments radiation injury and leads to increased infection and mortality in mice: molecular mechanisms. Free Radic Biol. Med. 53, 1152–1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.007 (2012).

Lang, E. et al. Conjugated bilirubin triggers anemia by inducing erythrocyte death. Hepatology. 61, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27338 (2015).

Zaccherini, G. et al. Prediction of nosocomial acute-on-chronic liver failure in patients with cirrhosis admitted to hospital with acute decompensation. JHEP Rep. 1, 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.07.005 (2019).

Trieb, M. et al. HDL-related biomarkers are robust predictors of survival in patients with chronic liver failure. J. Hepatol. 73, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.01.026 (2020).

Claria, J. et al. Systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis: characterization and role in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 64, 1249–1264. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28740 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Chen, P., Zhang, Y., Nie, Y. & Zhu, X. Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels predicting poor outcomes in patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 1001411. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1001411 (2022).

Rahimi, R. S. & Rockey, D. C. Acute on chronic liver failure: definitions, treatments and outcomes. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 32, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0000000000000265 (2016).

Luo, J. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: far to go-a review. Crit. Care. 27, 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04540-4 (2023).

Verdelho, M. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a Portuguese single-center reference review. GE Port J. Gastroenterol. 25, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000478988 (2018).

Hu, C. et al. Serum ammonia is a strong prognostic factor for patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Sci. Rep. 10, 16970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73603-1 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the medical staff in the Department of Hepatology for their support in providing information about patients. We also thank the patients for their willingness to participate. This research was supported by the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang (2023C03101), the Spring City Plan: The High-level Talent Promotion and Training Project of Kunming (Grant No.2022SCP002), and National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3602000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.J. and W.X. conceived of and designed the study, and searched related Literature. Y.Q.S., S.F.W.,and Y.C. were in charge of data collection and provided technique support. W.X. and S.F.W. performed analysis and generated the figures and tables.W.X. drafted the manuscript. W.X., Y.Q.S., B.J., L-l.T and L.L. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal surrogates before enrollment. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The data used in this study were anonymous prior to its use.

Data sharing statement

We are unable to provide access to our datasets for privacy reasons. The protocol and statistical analysis methods used in the study can be requested directly from the corresponding author after approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Xu, W., Chen, Y. et al. Early prediction of acute-on-chronic liver failure development in patients with diverse chronic liver diseases. Sci Rep 14, 28245 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79486-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79486-w