Abstract

Kinematic alignment (KA) in the short to medium term clinical outcomes is superior to the mechanical alignment (MA), but whether it will improve patients’ postoperative gait is still controversial. Understanding whether and how KA influences postoperative gait mechanics could provide insights into optimizing alignment philosophy to improve functional outcomes. To investigate the impact of KA versus MA in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) on the operated and contralateral native lower limbs by analyzing plantar pressure distribution during walking gait. This study was designed as a secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Thirty-seven patients were included, nineteen underwent KA-TKA and eighteen underwent MA-TKA, each with a native knee in the contralateral limb. Pressure-sensitive insoles were used to collect plantar pressure distribution of both limbs simultaneously during walking defined as medial-lateral load ratio (MLR). Perioperative characteristics including radiographic metrics (Hip-Knee-Ankle angle (HKA), mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA), and mechanical medial proximal tibial angle (mMPTA) and clinical outcomes (Oxford Knee Scores (OKS)) were compared between the two groups pre-operatively and 2-year postoperatively. Significant differences were found in postoperative radiographic metrics, with KA showing better OKS 1 year postoperatively (p = 0.021), lower mean HKA (p = 0.009) and mMPTA (p < 0.001). Other perioperative characteristics were similar between groups. In the pedobarographic analysis, the MA group demonstrated greater medial pressure distribution in forefoot compared to both the KA group (p < 0.001) and the contralateral native knee (p = 0.002). Besides, the MA group revealed a more lateral pressure distribution in rearfoot compared to the KA group (p = 0.007) and the contralateral native knee (p = 0.001). While there was no significant difference between KA and native group (p = 0.064 and p = 0.802, respectively). KA offered advantages over MA in restoring a more physiologic plantar pressure distribution at two years postoperatively. These results underscore the potential clinical benefits of adopting KA techniques in TKA procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gait function is associated with the health status and biomechanical performance of the knee5. Accordingly, the progressive deterioration associated with knee osteoarthritis (KOA) significantly influences gait mechanics, leading to considerable functional impairment. Throughout the course of KOA, individuals commonly experience alterations in lower limb alignment and plantar pressure distributions, profoundly influencing gait dynamics and overall mobility. Typically, in cases of varus knee deformity, it is common to observe hindfoot pronation and increase toe-out angle, serving as a compensatory response, although it is inadequate3,12.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) stands as a pivotal intervention for alleviating pain in end-stage knee osteoarthritis (KOA), while simultaneously improving gait function25. However, the optimal alignment strategy remains a subject of debate. Mechanical alignment (MA) techniques aim to align the prosthesis at a perpendicular angle to the mechanical axes, promoting even load distribution across the prostheses but disregards the inherent variability in individual anatomy and joint kinematics19. Conversely, kinematic alignment (KA) philosophy acknowledges the substantial phenotypic diversity, emphasizing the strategic placement of prostheses tailored to individual anatomical variations, thereby promoting better clinical and functional outcomes for patients undergoing TKA.

Although there have been many gait analysis studies comparing KA and MA, their results remain contradictory4,11,18,29. Pedobarographic analysis has been proven to be a useful clinical diagnostic tool in TKA, only a few pedobarographic exams have been applied in the field of TKA24. Despite good clinical and radiographic outcomes, plantar loading distribution changed statistically significantly after TKA9. Current evidence indicated that hindfoot alignment, toe-out angle and plantar pressure distribution are restored after TKA23. An observational study suggested that KA-TKA results in a more balanced plantar pressure distribution, similar to healthy controls, compared to MA-TKA. Additionally, KA-TKA achieves a more neutral alignment through the true mechanical axis than MA-TKA10. However, this study only controlled for the knee that underwent TKA on the included side, without controlling for the condition of the contralateral knee, which may introduce bias in the results due to the condition of the contralateral knee. Therefore, there remains a lack of research focusing on pedobarographic gait analysis between these two alignment philosophies.

This secondary analysis aims to fill this gap by focusing specifically on their respective impacts on plantar pressure distribution. Plantar pressure distribution is a crucial indicator of joint loading pattern and function post-TKA, with deviations from natural patterns potentially contributing to dissatisfaction, implant wear, and long-term functional limitations. The hypothesis was that KA will achieve better clinical outcomes compared to MA. And the plantar pressure distribution of the operated lower limb with varus knees after KA would be closer to that of the contralateral native lower limb compared to MA.

Materials and methods

Sample size estimation

The sample size for this study was estimated based on the primary outcome measure, the rearfoot medial/lateral peak pressure ratio, according to Kamenaga’s study using PASS 15 software (Kaysville, Utah, USA). The estimation employed One-Way Analysis of Variance F-Tests with the following parameters: Power = 0.8, Alpha = 0.1, number of groups = 3, K = 1. The calculation indicated that an average group sample size of 16 would be sufficient to detect significant differences. This study adheres to the CONSORT statement guidelines6.

Ethical approval

This study was designed as a secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee. All participants provided informed consent for inclusion before their participation in the study. The trial is registered at the Clinical Trial Registry (registration number: ChiCTR2100054927).

Patient selection

Patients undergoing primary unilateral TKA at a single tertiary institution between January 2022 to May 2022 were eligible to participate in the initial prospective, randomized controlled trial. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) III-IV KOA knees. The exclusion criteria included: (1) varus knee led by external deformity; (2) lower limb’s bone tumor; (3) previous surgery or previous fracture of the lower limb; (4) PCL dysfunction; (5) those with joint active infection or severe heart, lung, liver, kidney, blood and other medical diseases that cannot tolerate surgery. All TKAs were performed using cruciate-retaining prosthesis (ATTUNE, DePuy Synthes, Johnson & Johnson). Patients were randomized using hand-written numbers placed in opaque, sealed envelopes. The odd-numbered envelopes correspond to the KA group, while the even-numbered envelopes correspond to the MA group.

The inclusion criteria for the secondary analysis added the following conditions: (1) pre-operative varus knees (defined as hip-knee-ankle angle (HKA) < 180°); (2) the contralateral knee is the native knee with K-L 0-II; (3) without fixed deformities of ankle and foot.

Surgical technique

All patients received identical perioperative management protocol. TKA was performed under general anesthesia with the patient positioned supine. After knee flexion, an inflatable tourniquet was applied, and the knee joint was exposed via the subvastus approach. Additional procedures included the incision of the joint capsule, excision of the arthritic synovium and the anterior cruciate ligament, while ensuring preservation of the posterior cruciate ligament integrity. Furthermore, osteophytes located on the medial condyle of the distal femur and the medial aspect of the tibial plateau were removed.

For KA group, the modified kinematically aligned TKA were applied (restricted tibial cut)16,17. On the femoral side, measured resection was performed after estimating cartilage wear. On the tibial side, tibial osteotomy with a 3° varus deviation from the mechanical axis was performed for patients with an estimated postoperative mechanical medial proximal tibial angle (mMPTA) ≤ 87° by combining preoperative imaging planning with the intraoperative application of a customized 87° cutting block using the ‘double-check’ method. For patients with estimated mMPTA > 87°, measured resection was applied. And the posterior slope was set at 7 degrees.

For MA group, the procedure began with femoral intramedullary positioning, followed by a routine 6° valgus femoral condyle osteotomy. On the tibial side, extramedullary positioning is employed to ensure that the mechanical axis of the tibia is perpendicular, with the platform osteotomy performed at a posterior tilt of 5–7°. A gap block of appropriate thickness is then placed to test the alignment of the lower limbs. The posterior femoral condyle is externally rotated by 3° for the osteotomy, and soft tissue is released as needed to achieve proper alignment and balance.

For both groups, denervated treatment of the patella was performed, involving osteophyte removal and trimming of the patellar joint surface without resurfacing. The “thumbless test” was used intraoperatively to assess patellar tracking, while passive flexion and extension of the knee joint were performed to observe patellar positioning within the trochlear sulcus and for signs of lateral dislocation. If the test indicated a positive result, appropriate release of the lateral patellar retinaculum was undertaken.

Outcomes

All patients were followed up at 1 and 2 years postoperatively. Clinical outcomes were assessed using the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) at 1 and 2 years postoperatively. Radiographic assessments were conducted to evaluate the alignment and positioning of the prosthesis. The following radiographic metrics including HKA, mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA), and mMPTA were measured preoperatively and at 24 months postoperatively. The contralateral native knees were utilized as a control group.

Pedobarographic analysis was performed to determine the plantar pressure distribution during the 2-year follow-up. Participants were instructed to select appropriately sized footwear, each fitted with pressure-sensitive insoles containing 48 sensors (RX-ES40-48P, Shenzhen Taida Century Technology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, they were asked to walk a distance of 20 m at a self-selected pace. After at least two trials to reduce the risk of familiarization effect, data from three consecutive steps of both the left and right foot were recorded for each of the 48 sensors. For each patient, the medial and lateral boundaries of the forefoot and rearfoot were defined using the center of the insole. The anterior and posterior boundaries were independently determined by two researchers who were not involved in patient management and were then cross-validated by the researchers. An equal number of medial and lateral pressure sensors were included. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consultation with the corresponding author. Subsequently, the pressure values from the medial and lateral sides of both the forefoot and rearfoot were summed separately. The medial/lateral pressure ratio (MLR) was defined as the ratio of the summed medial pressure to the summed lateral pressure multiplied by 100 (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Firstly, the normality of the dataset was analyzed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using independent t-tests. The comparison of plantar pressure distribution data was conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The MA group had 1 missing value of postoperative radiographic data that was imputed at the median.

Results

Patient demographics

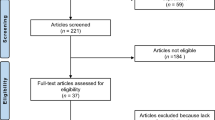

The study included a total of 37 patients, with 19 KA knees and 18 MA knees undergoing TKA. All patients were followed up at 24 months postoperatively (Fig. 2). The demographics and preoperative characteristics of the two groups were comparable. The mean age was 69.2 years for the KA group and 69.5 years for the MA group (P = 0.88). The proportion of females was slightly higher in the KA group (73.7%) compared to the MA group (66.7%), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.65). Other preoperative characteristics, including height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and side of TKA, showed no significant differences between the groups (Table 1).

Perioperative outcomes

Preoperative OKS and HKA were similar between the groups. Postoperatively, both groups showed significant improvements in OKS. The KA group achieved higher OKS scores compared to the MA group 1 year postoperatively (41.37 vs. 37.02, P = 0.02). However, the differences between KA and MA were not statistically significant during the 2-year follow-up (42.37 vs. 41.34, P = 0.42). However, significant differences were observed in postoperative radiographic metrics. The KA group had a mean postoperative HKA angle of 176.78°, compared to 178.51° in the MA group (P = 0.01). Additionally, mMPTA was significantly different between the groups (86.78° for KA vs. 90.14° for MA, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

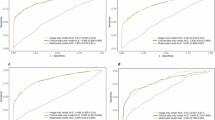

Pedobarographic analysis

Pedobarographic analysis revealed significant differences in the MLR between the KA and MA groups. For the forefoot MLR (fMLR), the KA group and the contralateral native knee showed a significantly lower value compared to the MA group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively) (Fig. 3). When comparing KA to the native group, the difference in fMLR was not statistically significant (P = 0.064). For the rearfoot MLR (rMLR), the KA and the native group demonstrated a significantly higher value compared to the MA group (P = 0.007 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 4). The comparison between KA and the native knee showed no significant difference (P = 0.802) (Table 2).

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that KA offers superior restoration of natural plantar pressure distribution in forefoot and rearfoot to contralateral normal knee when compared with MA. This also aligns with our initial hypothesis.

Studies have demonstrated that following the correction of varus knee with TKA, foot loading patterns can be restored in the majority of patients23. While Kamenaga indicated that KA produced a more balanced distribution of medial and lateral rearfoot pressure during walking through a comparative observational study of KA, MA, and healthy controls10. These findings are also consistent with our conclusions. Based on previous studies, the innovations of this study are as follows: (1) The evidence level of existing research has been elevated through the implementation of prospective cross-sectional study design; (2) By selecting unilateral KOA patients, this study incorporated self-control to reduce the impact of the potentially abnormal contralateral knees on plantar pressure distribution; (3) The initial application of pressure-sensitive insoles enables researchers to dynamically analyse data across consecutive gait cycles.

The benefits of KA can be attributed to its philosophy, which aims to replicate the patient’s native knee more closely than MA21. By preserving the natural joint line and ligament tension, KA may lead to more physiologic gait mechanics and better functional outcomes20. The clinical outcomes measured by the OKS also indicate patient-perceived benefits of KA over MA. Although the differences in OKS were not statistically significant in the 2-year follow-up, the trend towards better scores in the KA group suggests that patients may experience better functional outcomes and higher satisfaction with KA1,28,30. Considering the different alignment philosophies, both the KA and MA groups were able to ensure that the lower limb alignment was within ± 3° of their respective predetermined alignment targets, and the results for both groups are acceptable14.

There is no doubt that the gait of the lower limbs in patients with KOA worsens as the disease progresses. For patients with varus KOA, TKA can correct the varus deformity, thereby reducing the load on the medial compartment, improving knee adduction moments, and minimizing lateral trunk movement during walking26. Currently, existing evidence suggests that during short- to mid-term follow-up, KA functional scores and postoperative satisfaction are superior to MA13,27. Dossett found that the KA group had a greater distance walked prior to discharge in the early postoperative period compared to the MA group8. However, McNair reported that there were no advantages in walking speed and step frequency for the KA group at a 2-year follow-up18. The conflicting evidence prevents a conclusive explanation for the higher satisfaction especially focusing on function reported by KA postoperative patients compared to MA1.

In our study, both the KA group and the contralateral native group showed more even distributed pressure compared to the MA group during walking gait in the rearfoot. Besides, the KA group presented more laterally distributed pressure in the forefoot compared to the MA group, restoring it more similar to the contralateral native knee. These results support previous studies, indicating that KA can improve plantar pressure distribution patterns and allows patients to walk with a more native pressure distribution10,23. The forefoot plays an essential role during walking, especially in the push-off during the terminal stance phase of the gait cycle, where it helps push the body forward7. This role becomes even more crucial as walking speed increases. Generally, the toe-out angle increases after TKA to compensate the increased knee adduction moment26. While the KA technique reduced the knee adduction moment and toe-out angle by maintaining a constitutional varus alignment22. Naturally, with a smaller and more similar toe-out angle to the contralateral native knee, there will be a corresponding change in the foot pressure distribution. Therefore, KA may be able to generate a force distribution more closely resembling the natural state postoperatively. By restoring native plantar pressure distribution, KA may reduce the incidence of abnormal gait and decrease risk of falling, thereby enhancing patient satisfaction postoperatively2,15.

This study has certain limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and the follow-up period was limited to two years. Since some clinical and imaging indicators were not analyzed in the study, it is insufficient in certain aspects to evaluate the alignment of the entire lower extremity. Secondly, the selection criteria might be the reason for the relatively dispersed data in the ‘native’ group, as we only included patients with varus deformity in the knee undergoing TKA and limited the contralateral knee to K-L grades 0-II, without controlling for the alignment phenotype of the contralateral lower limb. Both KL I-II knees and different alignment phenotypes can potentially cause gait abnormalities. Also, due to the lack of postoperative OKS evaluation for the contralateral knees, the data for the native group is relatively dispersed. Additionally, the pressure-sensitive insoles used in this study have 48 sensors, but the number of the sensors may be limited. Therefore, more precise instruments may be needed to validate our results. Currently, evidence suggesting that while KA have better clinical efficacy than MA in the medium to long term follow-up, but the results are not definitive. While using a cruciate-retaining prosthesis in the MA group might cause posterior cruciate ligament laxity or constraint, particularly in patients with significant knee deformity, which could negatively impact by affecting joint stability, biomechanics, and functional recovery. This may potentially affect long-term outcomes. Therefore, further research with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up durations is warranted to validate these findings.

Conclusion

KA offers significant advantages over MA in restoring more natural plantar pressure distribution, which may contribute to better functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. These findings support the application of KA philosophy in TKA to achieve more physiologic postoperative gait mechanics. Further studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these benefits and to evaluate the long-term durability of KA in TKA.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abhari, S. et al. Patient satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty using restricted kinematic alignment. Bone Joint J. 103-b, 59–66 (2021).

Bączkowicz, D., Skiba, G., Czerner, M. & Majorczyk, E. Gait and functional status analysis before and after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 25, 888–896 (2018).

Bechard, D. J. et al. Toe-out, lateral trunk lean, and pelvic obliquity during prolonged walking in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis and healthy controls. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 64, 525–532 (2012).

Blakeney, W. et al. Kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty better reproduces normal gait than mechanical alignment. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 27, 1410–1417 (2019).

Bonnefoy-Mazure, A. et al. Walking speed and maximal knee Flexion during Gait after total knee arthroplasty: minimal clinically important improvement is not determinable; patient acceptable symptom state is potentially useful. J. Arthroplasty. 35, 2865–2871e2862 (2020).

Butcher, N. J. et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in Trial Reports: the CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 extension. Jama. 328, 2252–2264 (2022).

Doerks, F. et al. Contribution of various forefoot areas to push-off peak at different speeds and slopes during walking. Gait Posture. 108, 264–269 (2024).

Dossett, H. G., Estrada, N. A., Swartz, G. J., LeFevre, G. W. & Kwasman, B. G. A randomised controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee replacements: two-year clinical results. Bone Joint J. 96-b, 907–913 (2014).

Güven, M., Kocadal, O., Akman, B., Şayli, U. & Altıntaş, F. Pedobarographic Analysis in total knee arthroplasty. J. Knee Surg. 30, 951–959 (2017).

Kamenaga, T. et al. Comparison of plantar pressure distribution during walking and lower limb alignment between modified kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. J. Biomech. 120, 110379 (2021).

Kang, K. T., Koh, Y. G., Nam, J. H., Kwon, S. K. & Park, K. K. Kinematic Alignment in Cruciate retaining implants improves the biomechanical function in total knee arthroplasty during gait and Deep Knee Bend. J. Knee Surg. 33, 284–293 (2020).

Khan, S. S., Khan, S. J. & Usman, J. Effects of toe-out and toe-in gait with varying walking speeds on knee joint mechanics and lower limb energetics. Gait Posture. 53, 185–192 (2017).

Liu, B., Feng, C. & Tu, C. Kinematic alignment versus mechanical alignment in primary total knee arthroplasty: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17, 201 (2022).

MacDessi, S. J. et al. The language of knee alignment: updated definitions and considerations for reporting outcomes in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 105-b, 102–108 (2023).

Marino, G. et al. Long-term gait analysis in patients after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 113, 75–98 (2024).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Radiological and clinical comparison of kinematically versus mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 99-b, 640–646 (2017).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Intraoperative Soft Tissue Balance/Kinematics and Clinical Evaluation of Modified Kinematically versus mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. J. Knee Surg. 33, 777–784 (2020).

McNair, P. J. et al. A comparison of walking Gait following mechanical and Kinematic Alignment in total knee joint replacement. J. Arthroplasty. 33, 560–564 (2018).

Mercuri, J. J., Pepper, A. M., Werner, J. A. & Vigdorchik, J. M. Gap balancing, measured resection, and Kinematic Alignment: how, when, and why? JBJS Rev. 7, e2 (2019).

Nedopil, A. J., Howell, S. M. & Hull, M. L. Deviations in femoral joint lines using calipered kinematically aligned TKA from virtually planned joint lines are small and do not affect clinical outcomes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 3118–3127 (2020).

Nedopil, A. J., Howell, S. M. & Hull, M. L. Kinematically Aligned Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Calipered Measurements, Manual Instruments, and Verification Checks. In: Rivière C, Vendittoli PA, eds. Personalized Hip and Knee Joint Replacement;10.1007/978-3-030-24243-5_24. Cham (CH): Springer.

Copyright Implant survival and function ten years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty The Author(s). 2020:279–300. (2020).

Niki, Y., Nagura, T., Nagai, K., Kobayashi, S. & Harato, K. Kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty reduces knee adduction moment more than mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 26, 1629–1635 (2018).

Palanisami, D. R. et al. Foot loading pattern and Hind foot alignment are corrected in varus knees following total knee arthroplasty: a pedobarographic analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 28, 1861–1867 (2020).

Sehgal, A., Burnett, R., Howie, C. R., Simpson, A. & Hamilton, D. F. The use of pedobarographic analysis to evaluate movement patterns in unstable total knee arthroplasty: a proof of concept study. Knee. 29, 110–115 (2021).

Sharma, L. Osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 51–59 (2021).

Tazawa, M., Sohmiya, M., Wada, N., Defi, I. R. & Shirakura, K. Toe-out angle changes after total knee arthroplasty in patients with varus knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 22, 3168–3173 (2014).

Wang, G., Chen, L., Luo, F., Luo, J. & Xu, J. Superiority of kinematic alignment over mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty during medium- to long-term follow-up: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. (2024).

Winnock de Grave, P. et al. Higher satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty using restricted inverse kinematic alignment compared to adjusted mechanical alignment. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 30, 488–499 (2022).

Wang G, Chen L, Luo F, Luo J & Xu J. Kinematic and mechanical alignments in total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis with ≥ 1-year follow-up. J. Orthop. Sci. 29(5) 1226–1234 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2023.08.001

Funding

This work was supported by (1) Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation Projects (2022J011016), (2) the Major Scientific Research Project of Fujian Province (2021ZD01003), (3) Orthopaedics (National Clinical Key Specialty) (2023152).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W., L.C., G.Y.: acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript. G.W.,Y.Z. analysis of data. Y.Z., F.L., J.X.: critical revision and made final approval. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Chen, L. et al. Modified kinematic alignment better restores plantar pressure distribution than mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14, 27775 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79566-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79566-x