Abstract

The preservation of the left colic artery (LCA) during rectal cancer resection remains a topic of controversy, and there is a notable absence of robust evidence regarding the outcomes associated with LCA preservation. And the advantages of robotic-assisted laparoscopy (RAL) surgery in rectal resection remain uncertain. The objective of this study was to assess the influence of LCA preservation surgery and RAL surgery on intraoperative and postoperative complications of rectal cancer resection. Patients who underwent laparoscopic (LSC) or RAL with or without LCA preservation resection for rectal cancer between April 2020 and May 2023 were retrospectively assessed. The patients were categorized into two groups: low ligation (LL) which with preservation of LCA and high ligation (HL) which without preservation of LCA. A one-to-one propensity score-matched analysis was performed to decrease confounding. The primary outcome was operative findings, operative morbidity, and postoperative genitourinary function. A total of 612 patients were eligible for this study, and propensity score matching yielded 139 patients in each group. The blood loss of the LL group was significantly less than that of the HL group (54.42 ± 12.99 mL vs. 65.71 ± 7.37 mL, p<0.001). The urinary catheter withdrawal time in the LL group was significantly shorter than that in the HL group (4.87 ± 2.04 d vs. 6.06 ± 2.43d, p<0.001). Anastomotic leakage in the LL group was significantly lower than that in HL group (1.44% vs. 7.91%, p = 0.011). The rate of urinary dysfunction and sexual dysfunction in LL group is both significantly lower than HL group. Blood loss and number of harvested lymph nodes (LNs) of both RAL subgroups in LL and HL groups were significantly more than that in LSC subgroups. The anastomotic leakage in the RAL subgroup of HL group was significantly lower than that in LSC subgroup (0% vs. 14.89%, p = 0.018). LCA preservation surgery for rectal cancer may help reduce the blood loss, urinary catheter withdrawal time, the rate of anastomotic leakage and ileus, and postoperative genitourinary function outcomes. RAL can reduce the probability of blood loss and improve harvest LNs in patients with rectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In rectal cancer surgery, the optimal level for ligating the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) remains a subject of debate. Surgeons must choose between a high ligation (HL) at the IMA’s origin near the aorta and a low ligation (LL) below the left colic artery (LCA) origin1. Notably, HL at the IMA origin may increase the risk of anastomotic leakage2. Consequently, many surgeons opt for LL, which involves preserving the LCA while ligating the IMA after dissecting the surrounding lymph nodes3. The complexity of rectal cancer surgery escalates with the tumor’s proximity to the sphincter muscle and the depth of its aboral position4. There are two main approaches to handling the IMA during rectal cancer resection: either preserving the LCA and ligating the IMA after its bifurcation or directly ligating the IMA root without LCA preservation5.

In recent years, minimally invasive surgery has gained significant traction6. However, studies comparing the effectiveness of robotic-assisted and laparoscopic resections for rectal cancer are still limited. Robotic-assisted systems offer numerous advantages, such as enhanced comfort and maneuverability, tremor and motion filtration via computer systems, high-definition 3D binocular vision with magnification options, fluorescence capabilities, and a stable, surgeon-operated camera platform. These features represent a significant advancement in surgical technology7.

In our study, we analyzed data from patients who underwent rectal cancer resection at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery of Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital. We aimed to explore the perioperative outcomes of low ligation and high ligation resections for rectal cancer, comparing subgroups of robotic-assisted and laparoscopic surgeries.

Methods

All methods of our research were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by Declaration of Helsinki. We identified that the Ethics Committee of Northern Jiangsu Province People’s Hospital approved this research, including any relevant details. Informed consent was obtained from each patient preoperatively.

Patients

Inclusion criteria8: (1) 18 years of age and over; (2) low anterior resection for rectal cancer; (3) postoperative pathological diagnosis of rectal adenocarcinoma; and (4) informed consent signed prior to surgery.

Exclusion criteria8 : (1) recurrent rectal cancer; (2) emergency surgery; (3) preoperative and intraoperative detection of distant organ metastases or extensive implantation metastases in the abdominal cavity; (4) palliative surgery; (5) a postoperative pathology report that showed residual cancer cells at the proximal or distal resection margin; (6) no standard chemotherapy for tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging II or III after surgery; (7) synchronous colorectal carcinoma and other organ tumors; and (8) incomplete case data.

As displayed in Fig. 1, based on these criteria, we retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who underwent rectal cancer surgery at Northern Jiangsu People’s Hospital from April 2020 to May 2023. Out of 1,164 cases, 612 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 462 cases involved low ligation (LL) preserving the LCA (LL group), with 202 undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopy (LL-RAL subgroup) and 260 undergoing laparoscopy (LL-LSC subgroup). The remaining 150 cases involved high ligation (HL) without preserving the LCA (HL group), with 70 undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopy (HL-RAL subgroup) and 80 undergoing laparoscopy (HL-LSC subgroup).

Surgical procedure.

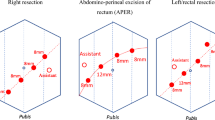

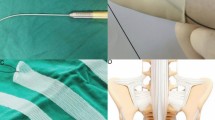

All patients underwent total mesorectal excision or partial mesorectal excision with D3 lymph node dissection while preserving the sphincter. In the HL group, the IMA was ligated and divided 2 cm from its origin (Fig. 2), and the inferior mesenteric vein was divided below the pancreatic margin. In the LL group, the LCA was identified and preserved while performing low ligation of the IMA (superior hemorrhoidal artery) (Fig. 2). Lymphadenectomy proceeded medially along the IMA to 2 cm from the aorta. After tumor resection, the bowel proximal to the pubic symphysis was checked to ensure tension-free condition. Splenic flexure mobilization was performed if necessary. To reconstruct the gastrointestinal tract, an end-to-end colorectal anastomosis was made, and a diverting ileostomy was added based on the surgeon’s evaluation of the anastomosis quality.

Evaluation of genitourinary function

Postoperative urinary and sexual functions were assessed 6 to 12 months after surgery through interviews and questionnaires. Each patient, along with a partner, completed a questionnaire about bladder and sexual sensations. Urinary function was evaluated based on incontinence, retention, pollakiuria, and residual urine volume, and dysfunction was classified into four grades9:: (I) normal function, no urination trouble; (II) mild dysfunction, pollakiuria, residual urine volume ≤ 50 mL; (III) moderate dysfunction, urination possible most times, residual urine volume > 50 mL, rare self-catheterization; and (IV) severe dysfunction, usual self-catheterization for incontinence or retention.

Erectile function was assessed using the International Erectile Dysfunction Index-5 (IIEF-5) questionnaire10: (I) normal erectile function, score > 11; (II) reduced erectile function, score 8–11, lower rigidity than preoperative; (III) loss of erectile function, score < 8, no erection. Ejaculatory function was evaluated with an ejaculation function score10: (I) normal ejaculation; (II) abnormal ejaculation, few or retrograde; (III) loss of ejaculation function, no ejaculation. Categories II and III in erectile and ejaculatory functions were defined as sexual dysfunctions.

Statistical analyses

A one-to-one propensity score-matched (PSM) analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 22.0, with a caliper of 0.02 to reduce confounding. Patients were grouped based on variables such as age, sex, BMI, ASA classification, tumor location, TNM stage, and surgical approach (laparoscopic or robotic). Out of 612 eligible patients, PSM yielded 139 patients in each group.

To control confounding, subgroup analyses were conducted based on the presence or absence of a protective ileostomy. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.

Results

Patient clinical characteristics

A total of 612 rectal cancer patients were included in this study, consisting of 245 men (40.0%) and 367 women (60.0%). Among these patients, 462 (74.5%) were in the LL group, and 150 (24.5%) were in the HL group. Table 1 provides the clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups. Post-propensity score matching (PSM), there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, history of abdominal surgery, cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes, preoperative smoking, preoperative malnutrition, ASA classification, tumor TNM staging, tumor size, surgical approach, distance between tumor and anus, and degree of tumor differentiation. Both the LL and HL groups were further divided into LSC and RAL subgroups. Tables 2 and 3 present the clinicopathological characteristics of the LL and HL subgroups post-second PSM scoring.

Operative findings

Table 4 summarizes the operative findings between the LL and HL groups. The LL group exhibited significantly less blood loss compared to the HL group (54.42 ± 12.99 mL vs. 65.71 ± 7.37 mL, p < 0.001). Urinary catheter withdrawal time was shorter in the LL group (4.87 ± 2.04 days vs. 6.06 ± 2.43 days, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in operation time (128.67 ± 26.03 min vs. 130.86 ± 8.64 min, p = 0.346), number of harvested lymph nodes (18.81 ± 2.89 vs. 19.54 ± 4.85, p = 0.126), or number of positive lymph nodes (5.71 ± 1.10 vs. 5.50 ± 1.64, p = 0.215) between the LL and HL groups. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in time to flatus (2.03 ± 0.79 days vs. 2.17 ± 0.57 days, p = 0.099), time to regular diet (3.76 ± 1.01 days vs. 4.01 ± 1.52 days, p = 0.105), and postoperative hospital stay (7.35 ± 2.24 days vs. 7.96 ± 3.44 days, p = 0.077).

As presented in Table 5, in the LL group, the RAL subgroup had significantly longer operation times than the LSC subgroup (132.69 ± 25.94 min vs. 117.41 ± 24.55 min, p = 0.009), but less blood loss (50.13 ± 12.3 mL vs. 58.1 ± 10.73 mL, p = 0.003), and more harvested lymph nodes (19.67 ± 3.13 vs. 17.69 ± 2.61, p = 0.003). No significant differences were found in the number of positive lymph nodes (5.54 ± 1.07 vs. 5.46 ± 1.29, p = 0.776), time to flatus (1.95 ± 0.79 days vs. 2.21 ± 0.73 days, p = 0.142), time to regular diet (3.59 ± 0.88 days vs. 3.79 ± 0.92 days, p = 0.318), or postoperative hospital stay (6.95 ± 2.01 days vs. 7.74 ± 2.30 days, p = 0.109).

Furthermore, as detailed in Table 6, in the HL group, the RAL subgroup also had longer operation times than the LSC subgroup (132.28 ± 7.61 min vs. 128.00 ± 9.07 min, p = 0.015), less blood loss (63.40 ± 6.85 mL vs. 66.68 ± 6.59 mL, p = 0.020), and more harvested lymph nodes (20.98 ± 4.99 vs. 18.53 ± 4.33, p = 0.013). No significant differences were noted in the number of positive lymph nodes (5.80 ± 1.47 vs. 5.30 ± 1.88, p = 0.187), time to flatus (2.11 ± 0.60 days vs. 2.28 ± 0.62 days, p = 0.177), time to regular diet (4.15 ± 1.60 days vs. 4.13 ± 1.44 days, p = 0.946), or postoperative hospital stay (7.85 ± 3.86 days vs. 8.34 ± 3.55 days, p = 0.524).

Operative morbidity

Table 7 details operative morbidity. The LL group had a significantly lower incidence of anastomotic leakage compared to the HL group (1.44% vs. 7.91%, p = 0.011), as well as a lower rate of ileus (2.16% vs. 7.91%, p = 0.028). No significant differences were observed in superficial surgical site infection (1.44% vs. 2.16%, p = 1.0), deep surgical site infection (1.44% vs. 2.88%, p = 0.68), anastomotic bleeding (5.76% vs. 4.32%, p = 0.583), anastomotic stenosis (1.44% vs. 2.16%, p = 1.0), bowel perforation (0% vs. 0.72%, p = 1.0), or reoperation rates (2.16% vs. 2.88%, p = 1.0).

For the LL group, Table 8 shows that the RAL subgroup had lower anastomotic leakage rates than the LSC subgroup (0% vs. 0.51%, p = 0.474), though this was not statistically significant. There were no significant differences in rates of superficial surgical site infection (2.56% vs. 0%, p = 1.0), deep surgical site infection (0% vs. 5.13%, p = 0.474), anastomotic bleeding (0% vs. 12.82%, p = 0.064), anastomotic stenosis (2.56% vs. 2.56%, p = 1.0), ileus (0% vs. 2.56%, p = 1.0), or reoperation (0% vs. 2.56%, p = 1.0).

In the HL group, as indicated in Table 9, the RAL subgroup had significantly lower anastomotic leakage rates than the LSC subgroup (0% vs. 14.89%, p = 0.018). No significant differences were observed in rates of superficial surgical site infection (2.13% vs. 4.26%, p = 1.0), deep surgical site infection (0% vs. 2.13%, p = 1.0), anastomotic bleeding (2.13% vs. 4.26%, p = 1.0), anastomotic stenosis (2.13% vs. 2.13%, p = 1.0), ileus (2.13% vs. 4.26%, p = 1.0), or reoperation (2.13% vs. 4.26%, p = 1.0).

Postoperative genitourinary function was assessed in 81 male patients (34 in the LL group and 47 in the HL group) with normal preoperative function, 6 to 12 months post-surgery. As shown in Table 10, in the LL group, 94.12% maintained normal urinary function (grade I), and 5.88% experienced grade II dysfunction, with no cases of grade III or IV dysfunction. In the HL group, 51.06% maintained normal function, with 19.15%, 21.28%, and 8.51% experiencing grade II, III, and IV dysfunction, respectively, showing a significant difference in total urinary dysfunction rates between the groups. No significant differences were observed between the LSC and RAL subgroups within both the LL and HL groups, as shown in Tables 11 and 12. No urinary dysfunction was reported in the LL-RAL subgroup.

For sexual function, all patients had normal preoperative sexual activity. Postoperative erectile and ejaculatory functions were significantly better in the LL group compared to the HL group (p < 0.05). In the LL group, 94.12% retained complete erectile and ejaculative capacities. In the HL group, 57.45% retained erectile capacity, and 61.7% retained ejaculative capacity. No significant differences were observed between the LSC and RAL subgroups within both the LL and HL groups. In the LL-LSC subgroup, 77.78% maintained erectile capacity, and 88.89% maintained ejaculatory capacity, while in the LL-RAL subgroup, all patients retained both capacities. In the HL-LSC subgroup, 56.25% maintained both capacities, and in the HL-RAL subgroup, 66.67% maintained both capacities.

Discussion

This study assessed perioperative outcomes of rectal cancer resections with and without preservation of the left colic artery (LCA), comparing low ligation (LL) and high ligation (HL) techniques. Our results indicate that LL provides operational efficiency and safety similar to HL, with advantages such as reduced blood loss, lower rates of anastomotic leakage and ileus, shorter urinary catheterization times, and improved genitourinary function. Additionally, LL procedures showed less blood loss and more lymph nodes harvested, particularly in robotic-assisted laparoscopic (RAL) surgeries compared to laparoscopic (LSC) ones.

The operating time for LL was not significantly longer than for HL. Sekimoto et al5. reported similar findings, noting no increase in operating time or intraoperative bleeding with LL compared to HL. Wei et al11. suggest that, for colorectal cancer surgery, RAL procedures have comparable safety and efficacy to traditional laparoscopic surgery. However, RAL subgroups showed longer operating times than LSC subgroups in both LL and HL groups (P< 0.01), consistent with Ferrara et al12., who found comparable operative times across various colorectal surgeries. This discrepancy is likely due to the additional setup time required for robotic arms and the intraoperative instrument changes13.

Lymph node metastasis is critical in rectal cancer prognosis14. Cirocchi et al15. demonstrated that thorough lymph node dissection at the IMA root, while preserving the LCA, does not compromise oncological outcomes, aligning with our findings. The robotic system, with its precise dissection capabilities and stable visual field, enhances lymph node retrieval16, explaining the higher lymph node counts in RAL subgroups. Furthermore, Sun et al17.. reported that the use of indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging during laparoscopic colorectal surgery enhances lymph node harvest, which could be combined with our findings to achieve more thorough lymphadenectomy. Similarly, as suggested by Mukai et al18., using ICG fluorescence to assess anastomotic blood supply may help reduce postoperative morbidity and alleviate the financial burden on patients. Anastomotic leakage is a significant complication in rectal cancer surgery. Factors such as blood flow and anastomotic tension are crucial in its prevention19. Liu et al20,21. reported that in HL surgeries, blood flow in the marginal arch decreases significantly over distance, leading to low blood supply efficiency. Dworkin et al22. noted that not preserving the LCA reduces intestinal blood flow by approximately 40%, particularly affecting elderly patients with atherosclerosis. Our study found a lower incidence of anastomotic leakage in the LL group, likely due to better blood perfusion. Additionally, RAL subgroup in the HL group exhibited a higher rate of anastomotic leakage compared to the LSC subgroup (P< 0.05). Surgical procedures can damage the abdominal wall and peritoneum, triggering immune responses that may lead to complications such as anastomotic leakage and ileus23. The robotic system’s precision reduces trauma to tissues, aiding faster bowel recovery24, and preserving the LCA enhances blood supply, potentially lowering complications25.

Voiding and sexual dysfunction are common postoperative issues after extensive rectal cancer surgeries, with reported urinary dysfunction rates between 7% and 70% and sexual dysfunction between 40% and 100%26. High ligation of the IMA can injure the hypogastric nerve, leading to urinary and ejaculatory dysfunctionse27,28,29. Our study found superior postoperative genitourinary function in the LL group compared to the HL group.

This study has several limitations. The sample size may have affected the robustness of the results. It was a nonrandomized controlled trial based on propensity score-matched data30, and variations in surgical techniques between surgeons could influence outcomes. Additionally, different propensity matching models for secondary outcomes were not constructed. Future multicenter, large-sample, randomized controlled trials are necessary to address these limitations.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this PSM analyzed single-center retrospective study suggest that the blood loss, urinary catheter withdrawal time, the rate of anastomotic leakage and ileus, and postoperative genitourinary function outcomes associated with LCA preservation in resection of rectal cancer are better than those associated with ligation of the artery at the origin of the IMA. Concurrent with this, the surgical approach with RAL can reduce the probability of blood loss and improve harvest LNs in patients with rectal cancer. Moreover, RAL surgery shows obvious advantages in prevent anastomotic leakage in high ligation. However, further multicenter randomized controlled trials are required to confirm the validity of these results in a broader context.

Data availability

The data of the study are available from the corresponding authors with reasonable request.

References

Hida, J. & Okuno, K. High ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer surgery. Surg. Today. 43 (1), 8–19 (2013).

Komen, N. et al. High tie versus low tie in rectal surgery: comparison of anastomotic perfusion. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 26 (8), 1075–1078 (2011).

Yasuda, K. et al. Level of arterial ligation in sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery. World J. Surg. Oncol. 14, 99 (2016).

Raab, H. R. [R1 resection in rectal cancer]. Chirurg. 88 (9), 771–776 (2017).

Patroni, A. et al. Technical difficulties of left colic artery preservation during left colectomy for colon cancer. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 38 (4), 477–484 (2016).

Gass, J. M. et al. Laparoscopic versus robotic-assisted, left-sided colectomies: intra- and postoperative outcomes of 683 patients. Surg. Endosc. 36 (8), 6235–6242 (2022).

Liao, G. et al. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials. World J. Surg. Oncol. 12, 122 (2014).

Luo, Y. W. et al. Long-term oncological outcomes of low anterior resection for rectal cancer with and without preservation of the left colic artery: a retrospective cohort study. Bmc Cancer ;21(1). (2021).

Saito, N. et al. Clinical evaluation of nerve-sparing surgery combined with preoperative radiotherapy in advanced rectal cancer patients. Am. J. Surg. 175 (4), 277–282 (1998).

Rosen, R. C., Cappelleri, J. C., Smith, M. D., Lipsky, J. & Pena, B. M. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 11 (6), 319–326 (1999).

Wei, P. L., Huang, Y. J., Wang, W. & Huang, Y. M. Comparison of robotic reduced-port and laparoscopic approaches for left-sided colorectal cancer surgery. Asian J. Surg. 46 (2), 698–704 (2023).

Ferrara, F. et al. Laparoscopy Versus robotic surgery for Colorectal Cancer: a single-center initial experience. Surg. Innov. 23 (4), 374–380 (2016).

Wang, X., Cao, G., Mao, W., Lao, W. & He, C. Robot-assisted versus laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 16 (5), 979–989 (2020).

Kanemitsu, Y., Hirai, T., Komori, K. & Kato, T. Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br. J. Surg. 93 (5), 609–615 (2006).

Cirocchi, R. et al. High tie versus low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer: a RCT is needed. Surg. Oncol. 21 (3), e111–e123 (2012).

Tang, B. et al. [Efficacy comparison between robot-assisted and laparoscopic surgery for mid-low rectal cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial]. Zhonghua Wei Chang. Wai Ke Za Zhi. 23 (4), 377–383 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Safety and efficacy of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging-guided laparoscopic para-aortic lymphadenectomy for left-sided colorectal cancer:a preliminary case-matched study. Asian J. Surg. (2024).

Mukai, T., Maki, A., Shimizu, H. & Kim, H. The economic burdens of anastomotic leakage for patients undergoing colorectal surgery in Japan. Asian J. Surg. 46 (10), 4323–4329 (2023).

Trencheva, K. et al. Identifying important predictors for anastomotic leak after colon and rectal resection: prospective study on 616 patients. Ann. Surg. 257 (1), 108–113 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. The New Concept of physiological Riolan’s Arch and the Reconstruction Mechanism of Pathological Riolan’s Arch after High Ligation of the Inferior Mesenteric artery by CT angiography-based small Vessel Imaging. Front. Physiol. 12, 641290 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Verification of blood flow path reconstruction mechanism in distal sigmoid colon and rectal cancer after high IMA ligation through preoperative and postoperative comparison by manual subtraction CTA. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 49 (7), 1269–1274 (2023).

Dworkin, M. J. & Allen-Mersh, T. G. Effect of inferior mesenteric artery ligation on blood flow in the marginal artery-dependent sigmoid colon. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 183 (4), 357–360 (1996).

Suwa, K. et al. Risk factors for early postoperative small bowel obstruction after anterior resection for rectal Cancer. World J. Surg. 42 (1), 233–238 (2018).

Giordano, L. et al. Robotic-assisted and laparoscopic sigmoid resection. JSLS ;24(3). (2020).

Wang, K. X., Cheng, Z. Q., Liu, Z., Wang, X. Y. & Bi, D. S. Vascular anatomy of inferior mesenteric artery in laparoscopic radical resection with the preservation of left colic artery for rectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 24 (32), 3671–3676 (2018).

Hojo, K., Vernava, A. M. 3, Sugihara, K., Katumata, K. & rd, Preservation of urine voiding and sexual function after rectal cancer surgery. Dis. Colon Rectum. 34 (7), 532–539 (1991).

Sugihara, K., Moriya, Y., Akasu, T. & Fujita, S. Pelvic autonomic nerve preservation for patients with rectal carcinoma. Oncologic and functional outcome. Cancer. 78 (9), 1871–1880 (1996).

Nesbakken, A., Nygaard, K., Bull-Njaa, T., Carlsen, E. & Eri, L. M. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 87 (2), 206–210 (2000).

Li, K. et al. Protective effect of laparoscopic functional total mesorectal excision on urinary and sexual functions in male patients with mid-low rectal cancer. Asian J. Surg. 46 (1), 236–243 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Preservation versus nonpreservation of the left colic artery in anterior resection for rectal cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Surg. 22 (1), 164 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Key Research Project of Jiangsu Commission of Health (NO. ZD2022047) and Yangzhou University International Academic Exchange Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: DWang, MJ, QZ; (II) Administrative support: Department of Gastrointestinal surgery of Northern Jiangsu people’s Hospital; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: MJ, QZ, LS, BL, WW; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: MJ, JJ, LS, YJ, J W, MA; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: MJ, QZ, JJ, QS, YW, BL, JR, LW, WW, DT; (VI) Manuscript writing: MJ; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We identified that the Ethics Committee of Northern Jiangsu Province People’s Hospital approved this research (2020KY-137), including any relevant details. Informed consent was obtained from each patient preoperatively. The study was also registered on ClinicalTrials (NCT06376227).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, M., Ji, J., Zhang, Q. et al. Comparison of robotic assisted and laparoscopic radical resection for rectal cancer with or without left colic artery preservation. Sci Rep 14, 28113 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79713-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79713-4