Abstract

Solving the problem of gas extraction from low-permeability coal seams is an urgent issue in the global coal industry, and exploring green and efficient mining methods has potential applications in this field. In this study, the No. 9 coal seam of the Guizhou Longfeng Coal Mine was selected as the research object. The method of using a hydraulic horizontal slit to create a compensation space and then synergizing it with the coal body’s own stress to decompress and increase the permeability of the coal body was studied through similarity simulation and numerical simulation experiments. This study showed that the slit can cause the overall development, expansion, and penetration of coal seam fissures. Thereby, a large number of fissures are produced in the coal seam and its upper rock layer, which form, as a whole, a “positive trapezoid” shape. The three stages of the slit produced 165, 487, and 1572 fissures, which unpressurized and increased the penetration of the coal and rock body. The slit causes the upper coal body to lose its support, and the original stress balance of the coal and rock is broken, forming a decompression zone. At the same time, the coal body below starts to expand and deform after losing the vertical stress. The decompression zone gradually expands up and down, and the stress on both ends of the compensation space becomes larger, forming a stress concentration area. After the overall displacement of the coal seam caused by the slit, a “positive triangle” area is formed. In the upper part of the area, six displacement dividing lines are created, which form five areas. The displacement shows the distribution characteristics of a large displacement in the middle and a small displacement at both ends. The results of the similarity simulation and numerical simulation experiments were verified. The study provides a new way of thinking for effectively preventing coal and gas protrusion and improving mining efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China possesses limited oil and gas reserves but significant coal resources. The country’s coal reserves and production rank among the largest globally. Therefore, coal is a crucial strategic resource for ensuring China’s energy security and stability as well as meeting its fundamental energy requirements. Coal plays a vital role in China’s economic development and industrial expansion1,2,3,4. However, in recent years, the escalation of mining operations has resulted in the gradual exhaustion of surface-level resources. Consequently, a shift towards deep mining practices is necessary5,6,7. In some countries, deep mining environments are characterized by harsh conditions, limited space, and the production of a series of toxic and harmful gases. Disasters threatening the lives and health of miners are common, and the safety of coal mines is a major issue8,9,10. The primary sources of risk impeding the secure production of coal mines include gas, impact pressure, coal dust, water damage, and fires. Among these, accidents caused by gases represent the most significant hazards, with the potential to result in catastrophic incidents involving severe casualties and extensive losses. Consequently, addressing gas-related issues has become a critical priority in coal mining11,12,13,14,15.

Gas is present in large quantities in coal seams and is profusely released when coal is mined; therefore, most mines in China face the threat of gas hazards during the production process16,17,18. The overwhelming majority of China’s mining regions exhibit coal seams with low permeability, which renders gas extraction a considerably more arduous undertaking19,20. Presently, the most commonly utilized technologies for pressure relief and penetration enhancement include protective layer mining, hydraulic pressure relief and penetration enhancement, blasting pressure relief, and gas injection and displacement21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Hydraulic pressure relief and penetration technologies, such as hydraulic slitting, punching, and fracturing, have the advantage of being highly efficient and green; therefore, they are widely used in mine gas control29,30,31,32. According to Liang et al.33, a fractal fracture basis for determining the crack initiation angle is derived by representing the irregularity of the crack in fractal dimensions. It was shown that the size of the hydraulic fracture initiation angle is related to the subdimension, ground stress difference, and Biot coefficient. Huang et al.34 compared the coal-breaking performance of ice abrasive water jets, pure water jets, and conventional abrasive water jets using a coupled smoothed particle hydrodynamics finite element method. The experimental results show that the performance of the abrasive water jet in breaking coal is better than that of the pure water jet, and the performance of the abrasive ice technique is similar to that of the conventional abrasive method; however, the energy consumption of the abrasive ice method is lower. Fan et al.35 investigated the effect of erosion time and ruby nozzle diameter on erosion performance. The results showed that the rock-breaking performance increased linearly with the extension of erosion time, and a clear cavitation area could be obtained when the ruby nozzle was larger than 0.6 mm. Liu et al.36 established a prediction model for the depth of a hard coal cut using a high-pressure water jet and proposed the concepts of “depth of cut energy index” and “medium nozzle diameter, high traversing speed, multiple cuts.” The results showed that the energy index of the depth of cut corresponded to an injection pressure of approximately 40–60% of the compressive strength of the rock. For Huang et al.37, the laminar surface was the main consideration. The influencing factors in shale crushing using a high-pressure abrasive water jet were investigated through experiments, and the research results showed that the angle between the jet direction and the parabolic surface played a dominant role in the rock-breaking performance. It was established that the bigger the angle, the deeper are the shale shot holes, whereas with a smaller angle, a fissure-like rock-breaking will be formed. Experts and scholars have conducted extensive research on high-pressure water jet cutting technology and have obtained many research results, some of which have been applied and promoted. The current research focuses on cracking, with the hole as the center and spreading to the surrounding area. However, this ignores the self-gravitational stress of the coal body itself and cannot achieve a wide range of cracking effects. Moreover, certain techniques are complicated and difficult to implement in large-scale applications.

Therefore, in this study, using similarity simulation experiments combined with numerical simulation, the hydraulic horizontal slit-stress synergistic technology is proposed to unpressurize and increase the penetration of the coal body. In the traditional method, cracking diffuses around the center of the holes. In the proposed innovative technology, horizontal slits are cut, which change the displacement characteristics of the coal body. The research results show that this method can cause the coal seam to produce a large number of cracks or even collapse, and the effect of unpressurization and penetration of the coal seam is obvious. This provides a reference for research on gas extraction and coal and gas prevention theory and has important theoretical and practical significance for the research of the overall unpressurization and penetration of the coal body. This method can improve the efficiency of gas extraction, reduce the production cost of coal mines, and reduce the occurrence of accidents. The synergistic effect of the space generated by the slits and the coal body’s own stresses causes the upper wide range of the coal body to produce cracks, fissures, and even collapse phenomena. The collapse phenomenon finally achieves the effect of unpressurization and penetration of the coal seam to improve the efficiency of gas extraction from the coal seam. In addition, this study investigated the deformation damage and stress.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation and determination of mechanical parameters

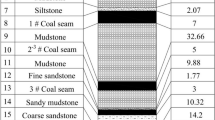

Samples were taken from the No. 9 coal seam of the Longfeng Mine in Guizhou Province, which is a medium-thick coal seam with medium ash, medium sulfur, extra-low volatile matter, high fixed carbon, and extra-high calorific value anthracite, with an average depth of 217 m. The mine, characterized by the presence of both coal and gas, has a history of coal and gas outburst accidents. The stratigraphic column of Coal Seam 9 is shown in Fig. 1.

Large coal samples from the seam were selected to prepare raw coal samples for uniaxial compression and Brazilian splitting experiments. To ensure the accuracy of the experimental data, all processing and physical and mechanical property tests strictly followed the standards of the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM), which recommends experimental methods for engineered rock. According to this standard, the uniaxial compression test specimen used was a cylinder with a diameter of 50 mm and height of 100 mm, whereas the Brazilian split test used a disc-shaped specimen with a diameter of 50 mm and height of 25 mm. To ensure that the samples were dimensionally accurate, they were precisely processed using specialized cutting and grinding equipment. The raw coal and specimens before and after processing are shown in Fig. 2.

Similarity simulation experiments

Similar material proportioning methods

To obtain a similar material in line with this experiment, it was tested under uniaxial compression with Brazilian splitting. The primary mechanical parameters are listed in Table 1.

The mechanical properties, including compressive strength, tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and Poisson’s ratio, of specimens of similar materials were determined38,39. To ensure the accuracy and consistency of these measurements, all the tests were performed using a TAJW-2000 microcomputer-controlled electrohydraulic servo rock three-axis experimental machine. These tests provide a detailed understanding of the damage morphology of specimens of similar materials under different conditions, and these data are essential for verifying the similarity of the models and for further research and analysis. The compressive strength and damage morphology of some similar specimens are shown in Fig. 3.

Based on the design similarity ratio and mechanical experiments of similar materials performed at this time, the ratio of similar materials for each rock layer was selected, as listed in Table 2. The mechanical parameters of similar specimens with different ratios varied significantly, with the variation interval of compressive strength ranging from 1.97 to 9.24 MPa, tensile strength from 1.01 to 3.84 MPa, and modulus of elasticity from 0.17 to 0.60 GPa. Combined with the mechanical parameters of the original coal rock samples and focusing on the compressive strength, the matching ratio in this experiment to meet the needs of similarity modeling for the No. 9 coal seam was sand: lime: gypsum = 7: 0.6: 0.4. After consulting a large amount of literature and related information, and because this experiment mainly focused on the fracturing of the No. 9 coal seam, mudstone and other rock bodies were not considered as the main objects of this study40,41,42,43,44. Based on the similar material mechanical experiments performed in this study, the ratio of similar materials for each rock layer was selected, as listed in Table 3.

Hydraulic horizontal slit-stress synergistic unloading and fracture similarity simulation experiments

For the experiments, a two-dimensional similarity simulation experimental platform was selected, with length × width × height of 1800 mm × 300 mm × 1850 mm. The experimental model size was length × width × height of 1350 mm × 300 mm × 1000 mm. According to the principle of similarity, the determined geometric phase had a similarity ratio of 1:10, the density similarity ratio was 1:1.6, and the dynamic similarity ratio was 1:1645. Based on the calculation results of the dynamic similarity coefficient, the vertical loading stress of the model was determined to be 0.68 MPa. The experimental method is shown in Fig. 4. The experimental setup included a slit-cutting device, hydraulic loading system, and experimental stand, as shown in Fig. 5. Considering the friction caused by the boundary of the model frame on the simulated rock formation, a layer of a smooth, rigid sheet was affixed to the boundary of the model frame to reduce the effect of friction. The experiment consisted of sand, lime, gypsum, and water prepared in a certain ratio and laid directly on the model frame.

A similarity simulation of the mining method was carried out by reserving a 30 cm pillar of coal at the left end of the open-cut eye and the right end of the stoping line in the model to eliminate boundary effects.The cutting position is 8 cm above the bottom of the coal seam, and the cutting runs through a similar model with a thickness of 30 cm and a height of 1 cm. The method is to borrow the principle of protective layer mining to create horizontal space as the compensation space for the movement of the coal body in a wider range to achieve the fracturing of the coal body. According to the principle of protective mining, when the maximum expansion deformation of the protected layer is more than 0.003, it means that the mining protective layer has the effect of unloading pressure protection on the protected layer46. Therefore, according to the similar model, when the height of the coal seam is 27 cm and the height of the designed slit is 1 cm, the maximum deformation and expansion rate is calculated as 0.037. During the laying of the model, eight strain-type earth pressure boxes were buried below and above the cut joints at 30, 45, 60, and 75 cm from the left boundary of the model. During the process of the hydraulic horizontal slit, the force situation, stress change rule, and influence of the slit on the overall decompression cracking of the coal seam below and above the slit were analyzed. The arrangement of the stress measurement points is shown in Fig. 6.

This simulation experiment was primarily conducted in the lower part of the coal seam to simulate a hydraulic horizontal cut seam. A total of 75 cm was excavated, which corresponds to a forward advance of 7.5 m on the prototype working face. The excavation was divided into three stages: 0–25 cm as the first stage, 25–50 cm as the second stage, and 50–75 cm as the third stage, with a total length of 75 cm; the advancing length of each hydrodynamic horizontal slit was marked. Before the excavation, the camera was switched on, and photographs were taken automatically every 10 s to observe the development of fissures and cracks in the model until the excavation was completed. A 10 h model stabilization period was required after completion of the hydraulic horizontal cut in the coal seam. The JM 3813 multifunctional static strain testing system and the DIC method were used for measurement and data acquisition during the experiment. The model was photographed after the completion of each hydraulic horizontal cut to record the cracks in the coal seam, movement of the rock layer, and collapse phenomenon, and the model was constructed as shown in Fig. 7.

Numerical simulation methods

Under the influence of load, the internal microcracks of coal and rock gradually expand at the micro-level. Once the cracks intersect, the strengths of the coal and rock decrease. At the macro-level, damage and failure appear along a certain direction, resulting in the overall failure. The PFC simulation software can apply forces corresponding to the model to simulate the processes of crack generation, propagation, and penetration. Therefore, to study the stress relief and fracturing effect of seam cutting in coal, in combination with the outcomes of previous similarity simulation experiments, numerical experiments were conducted to compensate for the drawbacks of the similarity simulation experiments, which were unable to present the crack evolution directly and in real time. The numerical calculation models used in this study were all two-dimensional models. The main object of study was the No. 9 coal seam, and the rock layer above the coal seam was not included in the study. The model size was 13.5 m in length and 10 m in width, and the model was divided into muddy siltstone, No. 9 coal, muddy siltstone, limestone, and fine sandstone, consecutively. The cutting height obtained through indoor similarity experiments is the product of coal seam thickness and maximum deformation expansion rate, and the result is 0.1 m. The macromechanical parameters of the model layers are listed in Table 4, and the particle fine-scale parameters are listed in Table 5.

To account for the computer performance and numerical simulation calculation efficiency, the strata situated far away from the influence range of coal seam mining fluctuations were simulated with large particles. To simulate the original rock stress environment, vertical stresses were applied to the upper walls of the model, and horizontal stresses were applied to the left and right walls. To maintain the model boundary stresses at a steady state, a servo mechanism was used to control the boundary walls, and the model included 32,899 particles. The construction of the model is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Because of the characteristics of the particles themselves, information such as stress and porosity cannot be obtained directly, and thus the variables related to stress and strain rate need to be measured with the help of a measuring circle. In this numerical experiment, the measuring circle was primarily used to measure the vertical and transverse stresses in an area. The function of the measuring circle is to extract the stress value of the model, and the average stress obtained has a close relationship with the size of the measuring circle. When the size of the measuring circle is too small, the calculation results are easily affected by random fluctuations and inaccurate, and if the measuring circle is too large, the local features may be covered up47,48. Taking the above factors into account, we consider choosing 0.30 m measuring circle. The arrangement of the modeled measuring circles is shown in Fig. 9, which includes a total of 442 measuring circles.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of coal body deformation and damage

The hydraulic horizontal cut destroys the original stress of the overlying coal body and redistributes the stress, thereby causing deformation damage to the coal body. The deformation damage to the coal body after the experiment is shown in Fig. 10.

In Fig. 10a, no obvious change is observed above and below the compensation space produced by the stage 1 slit. No visible cracks appear in the vicinity of the compensation space. It is presumed that the stress limit that the coal seam can withstand at this time has not been reached, and the coal body has not yet been ruptured significantly.

Figure 10b exhibits a large number of relatively obvious cracks near the compensation space when the cut advances to stage 2, and a stress concentration phenomenon occurs at the initial position of the cut, which produces obvious cracks (① in Fig. 10b). Horizontal off-seam fissures (② in Fig. 10b) appear at the boundary between the bottom of the coal seam and the muddy siltstone. After the hydraulic horizontal cut face in the coal seam produces the compensation space, under the dual action of the overlying coal rock’s own gravity as well as stress, the coal body in the upper part of the compensation space undergoes a series of bending deformations along the normal direction of the coal seam. The middle part of the coal body undergoes bending fracture, and the initial breakage produces an obvious vertical crack (③ in Fig. 10b). A distinct vertical crack appears at the upper end of the cut (④ in Fig. 10b).

As shown in Fig. 10c, when the cut advances to stage 3, the range of fracture development further expands, and the cracks generated before the compensation space formed by the hydraulic horizontal cut expand, which is more obvious than with the previous cracks, while other relatively obvious new cracks appear, as shown in Fig. 10c ⑤ ⑥ ⑦. The crack development and expansion generated at the initial position of the cut become more pronounced (① in Fig. 10c). The lateral off-stratum fissure at the bottom of the coal seam at the boundary with the muddy siltstone develops to approximately twice its original length (② in Fig. 10c). The hydraulic horizontal cuts in the coal seam approach the working face and produce a compensation space under the action of the overlying coal rock’s own gravity as well as stress. As a result, vertical crack development appears in the upper coal body, and the upper ④ cracks expand downward.

At the end of the simulated hydraulic horizontal slit advancement process, the overall development of the model fissures is obvious. Fissures can be observed almost all over the coal seam and its upper rock layer, and the fissures as a whole show a “positive trapezoidal shape,” unloading and fracturing the coal and rock body. From the overall analysis of the model, it is presumed that this results from the stress concentration effect, which leads to volume expansion and destruction of the coal rock, as well as further development, expansion, and penetration of the internal cracks. Simultaneously, owing to the plastic damage effect, the coal body in the plastic zone is damaged, the bearing capacity is reduced, numerous cracks are generated inside the coal body, and the stress of the surrounding coal rock is reduced.

Characteristics of changes in coal seam stress

The stress changes at the monitoring points are shown in Fig. 11. Monitoring points 1–4 above the coal seam showed two pressure unloadings during advancement. With the advance toward measuring points 1 and 2, a pressure-relief phenomenon first occurred at measuring point 1, and the pressure stabilized at approximately 70 kPa. Measurement point 2 was then depressurized, and the pressure remained at approximately 80–90 kPa for some time before depressurizing again to approximately 50 kPa. With the advance to measuring point 3, a first unloading occurred at this measuring point with an unloading pressure of approximately 110 kPa, and then a second unloading occurred with an unloading pressure of approximately 20 kPa, at which point the coal body at measuring point 3 fractured and sank. When the cutting face advanced to measuring point 4, due to the sinking of the coal body fractured at measuring point 3, the coal hardness became low. At measuring point 4, after a total of two unloading phenomena, the unloading pressure stabilized at 20 kPa. As can be observed in Fig. 9, the stress law changed at measurement points 5–8. When the hydraulic horizontal cut advanced over measurement points 5, 6, 7, and 8, the stress decompressed sequentially. The lowest decompression reached approximately 10 kPa, and decompression stabilization stress no longer occurred after the change.

From the analysis of the overall stress change rule shown in Fig. 11, when the measurement point was located at the front end of the cutting, the upper coal seam was in the loading state under the influence of concentrated stress. The stress was reduced in the upper seam after the measuring point was passed. When the working face advanced a certain distance, the stress at the measurement point gradually returned to a steady state. The coal seam underwent three processes: loading, unloading, and stabilization after the seam was cut.

Characteristics of coal rock displacement distribution

To analyze the displacement of the similar model during the experiment more intuitively, its surface was superimposed with the displacement cloud obtained from the scattering analysis, as shown in Fig. 12.

From Fig. 12a, it can be observed that when the working face advances, the displacement of both the coal body and overburden is small. When the working face advances to stage 1, the coal and rock bodies below the hydraulic horizontal cut lose the effect of vertical stress, and upward displacement occurs owing to their expansion. Meanwhile, the coal and rock bodies above lose the effect of the supporting force and undergo downward displacement, which is small. From Fig. 12b, it can be observed that the displacement develops above the hydraulic horizontal slit with the advancement of the working face, and the displacement of the coal rock and its area expand. The overall displacement of the coal rock shows the distribution characteristics of large displacements in the middle and small displacements at the two ends, and the peak displacement is located in the middle and upper areas of the hydraulic horizontal slit. As shown in Fig. 12c, as the working face advances and the displacement develops to the uppermost end of the model, the coal and rock body below the hydraulic horizontal cut undergo an upward expansion displacement, and part of the area appears to have a larger expansion displacement, which indicates that the coal body below the hydraulic horizontal cut effectively relieves the pressure. The displacement of the coal rock body above the hydraulic horizontal slit gradually decreases along the middle of the hydraulic horizontal slit to both sides, a displacement demarcation line is formed at the two ends of the hydraulic horizontal slit, and the distribution of displacement is presented as an “inverted trapezoidal” area.

From the displacement pattern, when the working face advanced to stage 1, the coal body and overburden mainly moved and deformed in the horizontal direction, and the displacement was small, which was the initial deformation period. When the working face advanced to stage 2, horizontal and vertical displacements occurred simultaneously, and the amount and area of coal and rock displacements rapidly expanded in a short period of time, which was the period of intense deformation. After the working face advanced to stage 3, the displacement speed on both sides of the cut seam decreased, the deformation amount started to weaken, the upper coal seam was gradually stabilized, and the deformation entered the recession period. Therefore, the displacement of the coal rock after a hydraulic horizontal slit is mainly divided into three displacement and deformation cycles: initial, violent, and stable.

Simulation results and analysis

To accurately simulate the crack initiation and expansion of the underground coal body during the numerical simulation study of hydraulic horizontal cuts, the simulation procedure consisted of the calibration of fine parameters, initial ground stress field equilibrium, application of hydraulic pressure, re-equilibrium of the ground stresses, excavation, and computational solving. In the hydraulic horizontal slit simulation process, to start the slit, the hydraulic horizontal slit direction goes from left to right, and the slit process is divided into three stages, sequentially advancing 2.5 m in each stage. The simulation of the process, from stage 1 to stage 3, is shown in Fig. 13.

Evolution of coal rock fissure extension in hydraulic horizontal cuts

The evolution of the emergence and expansion of fine-scale fissures is a key feature in the study of the development and expansion of fissures formed by unloading and fracturing of coal bodies with hydraulic horizontal cuts. The generation of inter-particle fissures is shown in Fig. 14, where the purple circle represents the particle entity and the red line segment denotes the fissure.

The evolution of coal rock fissure extension at different stages is shown in Fig. 15. Through the comparison, it was found that at the initial stage of the cut (500–14000 steps, Fig. 15a,b), the compensation space began to be generated, the coal body above the compensation space was subjected to its own stress, and the original support force disappeared, resulting in the breaking of the initial stress equilibrium. At the same time, the disappearance of the vertical stress in the coal body below produced a small expansion and deformation, and coal body cracks were developed around the compensation space, along with 165 interconnected secondary cracks. During the second stage of the cut (20,500–38,000 steps, Fig. 15c,d), the transverse fissures in the coal body above, which penetrated downward into the compensation space, continued to expand and extend but with a reduced scope. Simultaneously, the transverse fissures continued to expand and extended significantly towards the end of cutting stage 2, and the amount of coal body movement and bending continued to increase, at which time the number of fissures reached 652. As the width of the cut continued to increase (40,500–115,000 steps, Fig. 15e,f), a large number of fissures appeared in the coal body above the center of the stage 3 cut. The coal body collapsed and slumped and was then re-compacted, with the coal body below being subjected to large stresses, causing the fissures of the coal body to undergo a large-scale extension. The diagonal fissures in the coal body above the slit continued to expand and extend and eventually connected with each other, at which time the number of fissures reached 2,224, and the coal rock fissures as a whole showed a “positive trapezoidal” contour. A comparison of calculation steps 1, 2, and 3 with the cumulative number of fissures is shown in Fig. 16, where it can be observed that the fissure development in stage 3 is the most obvious, followed by that in stage 2, whereas the fissure development in stage 1 is poor. The number of fissures generated after the stability of fissure development in stages 1, 2, and 3 are 165, 487, and 1572, respectively, which reveals that the number of fissures developed in the coal body increases with the increase in the cutting distance.

From the overall model, the distribution pattern of cracks after coal body decompression shows a “positive trapezoid shape,” and compared with the crack development in the area of hydraulic horizontal slit in stage 3, the crack development in the area of hydraulic horizontal slit in stages 1 and 2 is more obvious and intensive. This indicates that the effect of coal fracturing is more prominent in the area where hydraulic horizontal cutting is carried out first. Three reasons presumably explain this pattern. First, the coal cracks formed in the stage 1 slit continued to expand during stage 2 under the influence of the advance of the hydraulic horizontal slit face and the continuing effects of coal stresses, whereas the coal cracks generated in stages 1 and 2 continued to expand and extend under the influence of the hydraulic horizontal cutting face advancement and coal body stress in stage 3. Second, the coal body in stage 2 was in the middle of the hydraulic horizontal slit, where the coal body above the central compensation space was subjected to greater stress. The coal body was subjected to stress exceeding its maximum destructive tolerance range, and it collapsed and slumped. Third, the coal body collapsed directly down the fissures in stages 1 and 2 after the hydraulic horizontal slit in stage 3. The coal body stresses were directly unloaded and did not act directly on the coal body in stage 3.

Stress dynamic evolution laws

The PFC software was used to obtain the rock stress data in the first and third directions, and the stress data were processed using Python to obtain stress cloud maps at different stages, as shown in Fig. 17.

As shown in Fig. 17a, stage 1 indicates that the original stress balance inside the coal rock body is changed, and the stress field inside the coal rock body is redistributed with the emergence of pressure relief zones. Areas of stress concentration appear on both sides of the cut, but the right stress concentration area is larger and more pronounced than the left stress concentration area. The stresses at the bottom of the model show a gradual decrease with the calculation steps. When stage 2 is carried out, as shown in Fig. 17b, the compensation space inside the coal body is extended to 5 m, and the range of the pressure relief area increases. The pressure relief area extends upwards and through, and it extends downward to the bottom of the model. Stress-supporting zones appear at the left and right ends of the hydrodynamic horizontal slits, which are subjected to the stresses of the coal body. In addition, after 60,000 steps, the coal rock stress returns to equilibrium, the stress concentration on the left side is greater than that on the right side, and the stress concentration area at the bottom of the model disappears. Finally, through the study of stage 3, it was found that, as shown in Fig. 17c, the coal rock stress was restored to the stage of stress equilibrium after completing the advancement of the slit, the area of stress concentration on both sides was well developed, and the phenomenon of stress concentration on the left side was smaller than that on the right side. In Fig. 18, the kinetic energy curves for stages 1, 2, and 3 are compared and analyzed. It is found that the kinetic energy of stage 3 is greater than that of stage 2, which is greater than that of stage 1. This indicates that with the increase in the distance of the hydraulic horizontal cut, the kinetic energy gathering inside the coal rock is more obvious and greater. Moreover, a stress rebound phenomenon occurs after the unloading of pressure in stages 1 and 2, which is caused by self-gravitational stress; the overlying coal body moves downward, and the area that has been unloaded is re-compacted. The kinetic energy of the second agglomeration in stage 3 is greater than that of the first, and in conjunction with the fissure extension analysis, it is hypothesized that as the distance between the hydraulic horizontal cuts increases, an overall large-scale collapse of the coal face in the compensatory space occurs, resulting in the kinetic energy of the second agglomeration being greater than that of the first agglomeration.

From the perspective of energy release, the essence of coal unloading fracturing is energy transfer and release. When the kinetic energy in the coal rock body above the hydraulic horizontal cut reaches a certain level, the kinetic energy is instantly released, at which time a large number of fissures sprout in the coal rock body. Macroscopically, bending deformation of the coal rock body above the compensation space and expansion and deformation of the coal body below can be observed. When the bending deformation of the coal body reaches the limit of its ability to withstand, the coal body ruptures or even collapses. The kinetic energy curve then continues to fluctuate, indicating that the model generates fissures at a faster rate during this phase, macroscopically compensating for the continued destruction of the coal rock mass above the space. Finally, the kinetic energy fluctuation appears in the flat zone, and the kinetic energy value is significantly lower, indicating that the development of the coal rock body fractures gradually stabilizes in this stage, with fewer newly generated fractures.

Analysis of coal rock particle displacement evolution

The calculation results were processed using the built-in program in the PFC software platform, where the velocity vector diagram indicates the motion trend of the unit particles and the color indicates the velocity magnitude, to obtain the displacement trend of the particles in the model of the computational solving process, as shown in Fig. 19.

When advancing to stage 1 (Fig. 19a), the coal body above the compensation space is affected by the coal body’s own stress and is unsupported, and its stress field and unloading range change, causing the coal particles above the compensation space to move slightly. The coal particles below the compensation space undergo a slight expansion and deformation owing to the loss of the vertical stress, which causes the coal particles to move slightly. In addition, the amounts of movement and bending of the coal body in the later part of stage 1 exceed its maximum damage tolerance range, and the cracks in the coal body above penetrate, resulting in the collapse and slumping of the coal body particles. The maximum displacement is reached at this time. When advancing to stage 2 (Fig. 19b), the displacement of the coal particles on the left side of the cut is the largest, the displacement of coal particles above the middle of the hydraulic horizontal cutting is the second largest, and the displacement at the right end of the hydraulic horizontal cut is the smallest. At this time, the displacement pattern shows a trend of gradual decrease in the displacement from left to right. Subsequently, the displacement range of coal particles does not change significantly, but the displacement increases. The overall displacement pattern at this stage shows that the displacement of the left side of the hydraulic horizontal slit is the largest, followed by that at the middle, whereas that at the right side is the smallest. When advancing to stage 3 (Fig. 19c), the amount and range of displacement of the coal particles above the middle of the hydraulic horizontal slit first increases, the coal particles above the right side of the hydraulic horizontal slit begin to be displaced, and the inclined interface line on the right side begins to move to the right. Subsequently, six symmetrically distributed displacement-dividing lines begin to appear in the middle of the cut, and the two outermost displacement-dividing lines begin to tilt outwards, forming five regions. The middle two strips form the region with the largest displacement; the next two strips at the left and right form the region with the second-largest displacement; and the left and right three strips form the region with the smallest displacement. Finally, the displacement of coal particles above the middle of the hydraulic horizontal cut continues to increase, but the range does not increase. At this time, the displacement of coal particles above the right part of the middle and the overall displacement of the right side of the area are approximately the same. The area formed by the two displacement dividing lines in the middle of the area becomes larger, but the position of the left and right sides of the second area remains unchanged. At the same time, the formation of the area becomes smaller, and the angle of inclination of the left and right sides of the third area remains approximately unchanged.

Conclusions

In this study, the No. 9 coal seam of the Longfeng Coal Mine in Guizhou Province was used as a similarity simulation experimental object. Through similarity simulation and numerical simulation experiments, the effect of coal unloading and fracturing was studied, revealing the deformation and damage of the overlying coal body, the characteristics of the coal seam stress change, and the coal rock displacement distribution features. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

-

(1)

Through similarity simulation and numerical simulation experiments, the crack development and distribution law characteristics were analyzed. The results show that hydraulic horizontal cuts caused the expansion of the upper coal rock body, along with bearing capacity decline and a destructive effect. The internal cracks in the coal body developed and expanded, and the cracks as a whole showed a “positive trapezoidal shape.” In addition, owing to the plastic destructive effect caused by the reduction in the surrounding coal rock stress, a large number of cracks within the coal body enhanced the role of the unloading pressure in increasing fracturing.

-

(2)

The coal seam underwent loading, unloading, and stabilization during hydraulic horizontal seam cutting. First, under the influence of the concentrated stress in the cut seam, the kinetic energy in the coal rock body, which is in the loading state at this time, gathers to a certain degree and is then released. When the bending deformation of the coal body reaches its limit, it ruptures and collapses, entering in the unpressurized state. Finally, the kinetic energy value decreases, the kinetic energy fluctuation enters the leveling-off zone, and the stress gradually returns to a steady state.

-

(3)

The range of the displacement variations increases as the working face advances. The range of influence of the hydraulic horizontal cuttings on the displacement changes in the overlying coal seam is significantly larger than that in the right and left sides. Simultaneously, the coal seam continues to collapse downward under its own stresses. Then, the stress equilibrium is reached, and no further significant changes occur.

-

(4)

After the hydraulic horizontal slit, the displacement of the coal rock body is mainly divided into three cycles: initial, violent, and stable. The initial coal and rock bodies are mainly displaced horizontally and move in small amounts. The amount and area of coal rock displacement during the intense period can expand rapidly in a short period of time. Then, a stabilization phase of the coal rock body displacement appears, and the deformation decreases until it finally stops.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article. Because some data of this paper will be used in the next research plan of the research group, the data sets generated and/or analyzed in this study are not public, but reasonable requirements can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

References

Hu, L., Feng, Z., Zhou, D. & Wang, X. Mechanisms and field application of in-situ heat injection-enhanced gas drainage. Energy 284, 128729 (2023).

Sang, M. & Shen, L. An international perspective on carbon peaking status between a sample of 154 countries. Appl. Energy 369, 123580 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Study on the mechanism of SiO2-H2O nanofluid enhanced water injection in coal seam. Appl. Surf. Sci. 658, 159843 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Effect of SiO2-H2O nanofluids on wettability of pulverized coal and the modification mechanism. Fuel 359, 130396 (2024).

Tang, C. et al. Study Concerning the Supercritical Adsorption Behavior of Shale gas that Analyzed Different Adsorption Mechanisms (Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 2024).

Cao, Z., Gu, Q., Huang, Z. & Fu, J. Risk assessment of fault water inrush during deep mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32(2), 423–434 (2022).

Du, K., Bi, R., Khandelwal, M., Li, G. & Zhou, J. Occurrence mechanism and prevention technology of rockburst, coal bump and mine earthquake in deep mining. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources 10(1), 1–35 (2024).

Kwinta, A. & Gradka, R. Analysis of the damage influence range generated by underground mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 128, 104263 (2020).

Ben-Awuah, E., Richter, O., Elkington, T. & Pourrahimian, Y. Strategic mining options optimization: open pit mining, underground mining or both. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 26(6), 1065–1071 (2016).

Lai, F. et al. The environmental performance of mining operations: comparison of alternative mining solutions in a life cycle perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 315, 128030 (2021).

Yang, G. et al. New insights into dynamic disaster monitoring through asynchronous deformation induced coal-gas outburst mechanism of tectonic and raw coal seams. Energy 295, 131063 (2024).

Du, X. et al. Coal damage and energy characteristics during shallow mining to deep mining. Energy 291, 130375 (2024).

Liu, T. & Liu, S. The impacts of coal dust on miners health: a review. Environ. Res. 190, 109849 (2020).

Qian, J., Wang, W., Ma, L., Dang, B. & Sun, X. Identification of preferential flow paths by hydraulic tomography compared with tracer test and the groundwater contour map in coal mine water hazard area. J. Hydrol. 631, 130816 (2024).

Yao, Y. et al. Theoretical and numerical study on critical velocity and driving force for preventing smoke backlayering in a connection roadway fire of coal mines. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 127, 104566 (2022).

Fang, H. H. et al. Coupling mechanism of THM fields and SLG phases during the gas extraction process and its application in numerical analysis of gas occurrence regularity and effective extraction radius. Pet. Sci. 19(3), 990–1006 (2022).

Fan, C. et al. Spatial–temporal evolution and countermeasures for coal and gas outbursts represented as a dynamic system. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(9), 6855–6877 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Study on the effect of multiple non-breathable gangue occurrence on gas migration in coal seams. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109190 (2022).

Hou, P. et al. Influence of liquid nitrogen freeze–thaw cycles on mechanical behaviors and permeability properties of coal under different confining pressures. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(4), 2625–2644 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. N2 injection to enhance gas drainage in low-permeability coal seam: a field test and the application of deep learning algorithms. Energy 290, 130010 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Wen, Z.-j. Safe strategy for coal and gas outburst prevention in deep-and-thick coal seams using a soft rock protective layer mining. Saf. Sci. 129, 104800 (2020).

Yang, W. et al. Integration of protective mining and underground backfilling for coal and gas outburst control: a case study. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 157, 273–283 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. Impact analysis of pressure-relief blasting on roadway stability in a deep mining area under high stress. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 110, 103781 (2021).

Zhao, D. et al. Study on parameter optimization of deep hole cumulative blasting in low permeability coal seams. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 5126 (2022).

Cai, J. et al. Risk assessment of dynamic disasters induced by gas injection displacement in coal seams. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 128, 41–49 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Experimental research and application of drilling and blasting with directional damage-reduction shaped charge. Sci. Rep. 14, 9549 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. Research on directional rock blasting based on different slotted pipe materials of the combined charge structure. Sci. Rep. 14, 7394 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Directional rock blasting using shaped charges using combined charge liners with different shapes. Energy Sci. Eng. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1587 (2023).

Ge, Z. et al. Experimental study on the characteristics and mechanism of high-pressure water jet fracturing in high-temperature hard rocks. Energy 270, 126848 (2023).

Xu, D., Tao, Y., Zhou, Z. & Hou, C. Study of the law of hydraulically punched boreholes on effective gas extraction radius under different coal outputs. Shock Vib. 2020(1), 8858091 (2020).

Schultz, R. et al. Hydraulic fracturing-induced seismicity. Rev. Geophys. 58(3), e2019RG000695 (2020).

Xiong, Q. & Hampton, J. C. A laboratory observation on the acoustic emission point cloud caused by hydraulic fracturing, and the post-pressure breakdown hydraulic fracturing re-activation due to nearby fault. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54(12), 5973–5992 (2021).

Liang, X. et al. Role of fractal effect in predicting crack initiation angle and its application in hydraulic fracturing. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55(9), 5491–5512 (2022).

Huang, F., Mi, J., Li, D., Wang, R. & Zhao, Z. Comparative investigation of the damage of coal subjected to pure water jets, ice abrasive water jets and conventional abrasive water jets. Powder Technol. 394, 909–925 (2021).

Fan, C. X., Li, D., Kang, Y. & Zhang, H. T. Effect of low-speed Waterjet Pressure on the rock-breaking Performance of Unsubmerged Cavitating Abrasive Waterjet (Petroleum Science, 2024).

Liu, F., Wang, Y., Huang, X., Song, G. & Wang, Y. A New Prediction Model for Cutting Depth of Hard Rock Using High-Pressure Water Jets1–19. (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024).

Huang, F., Zhao, Z., Li, D., Mi, J. & Wang, R. Investigation of the breaking manifestations of bedded shale impacted by a high-pressure abrasive water jet. Powder Technol. 397, 117021 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Experimental study of similar simulated material proportioning for small scale models. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 41(3), 1689–1702 (2023).

Shi, Y., Ye, Y., Hu, N., Huang, X. & Wang, X. Experiments on material proportions for similar materials with high similarity ratio and low strength in multilayer shale deposits. Appl. Sci. 11(20), 9620 (2021).

Cheng, W., Sun, L., Wang, G., Du, W. & Qu, H. Experimental research on coal seam similar material proportion and its application. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 26(5), 913–918 (2016).

Zeng, C., Zhou, Y. & Xiaoding, X. Research on the ratio of similar materials in water-absorbent mudstone based on fuzzy mathematics. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 4289 (2024).

Sun, P. et al. Experimental study on the ratio model of similar materials in the simulation test of coal and gas outburst. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 13513 (2021).

Liu, G., Wang, D., Zan, Y., Wang, S. & Zhang, Q. Feasibility Study of Material Deformation and Similarity of Spatial Characteristics of Standard Coal Rocks. Processes 12(3), 454 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. Similarity criteria and coal-like material in coal and gas outburst physical simulation. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 5, 167–178 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. A directional framework of similarity laws for geometrically distorted structures subjected to impact loads[J]. Int. J. Impact Eng. 161, 104092 (2022).

Xie, H. et al. Evolution of fissures and pressure discharge of gas caused by mining of the upper protective layer of a coal seam. Sci. Rep. 13, 2561 (2023).

Kang, C. & Chan, D. Numerical simulation of 2D granular flow entrainment using DEM[J]. Granul. Matter 20(1), 13 (2018).

Chen, X., Feng, Z. & Cheng, C. Numerical Study on Anisotropic Influence of Joint Spacing on Mechanical Behavior of Rock Mass models under Uniaxial Compression. Energies 13, 6698 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support provided by the funders.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Guizhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Qian Ke He Platform Talent CXTD [2023] General 030), Guizhou Provincial of Social Funding Projects (LDLFJSFW2024-9), the National Natural Science Foundation (52474127).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. Methodology: L.Z., K.L. Software: L.Z., K.L. Experiment: L.Z., K.L. L.W. Writing—original draft: L.Z. Writing—final draft: L.Z., Y.Z., L.W., J.H, B.Y. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, K. et al. Hydraulic horizontal slit-stress synergistic unloading fracturing in coal seams. Sci Rep 14, 28021 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79809-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79809-x