Abstract

As the global pursuit of renewable energy intensifies and the demand for offshore wind turbines rises, a comprehensive understanding of the coupling response characteristics of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions has become increasingly crucial. This paper reports on a wave flume experiment and seeks to contribute valuable insights by examining the coupling response of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves exerting a relentless influence. The experimental results indicate that the impact of waves on monopiles is significant: there is greater pressure on the wave facing surface of the offshore piles than the other faces, and the pressure increases with increased wave height as well as the height of the monopile. The wave impact also gives rise to pile motion, squeezing the soil near the monopile and causing gradual pore water pressure around the monopile, and when the wave impact is strong enough, the monopile loses stability. Finally, the experimental results indicate significant differences in the coupling response characteristics of an offshore monopile, the seabed, and waves in various sea conditions. When the wave height was small, the pore water pressure attenuated quickly in the direction of the depth of the seabed; however, as the height and period of waves increased, when the test wave height was more than 18.6 cm and the period was more than 1.63 s, the dynamic pore water pressure around the monopile first decreased and then increased along the depth direction, which, generated by the wave impact, led to vibration and squeezing of the soil near the monopile leg. This indicates that the closer the pile bottom, the more intense the squeezing. By investigating this development across different sea conditions, this study provides a nuanced understanding that can inform the design of offshore monopiles in the face of various marine environmental challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The conflict between the increasing demand for energy resources and increasingly stringent carbon dioxide emissions from the climate and environment due to the rapid development of the economy results in a large quantity of offshore wind turbines being applied in ocean engineering, which has tremendous potential to contribute to the decarbonization of the power sector. In terms of maintenance and management convenience, economic cost, etc., monopile is a commonly used foundation type for supporting offshore wind turbines in nearshore waters1. However, the seabed foundation near the sea is often a new, rapidly deposited soil layer, which is soft and less dense, has low bearing capacity, and is prone to instability. Under continuous and complex wave impacts (such as waves with periodic wavelengths), a monopile structure is more unstable than an offshore jacket platform structure for wind power support, and it is also more prone to instability under complex sea conditions2. Unlike the stress state of a monopile on land, Offshore structures withstand dynamic wave loads during their service life, which can be described as a process of monopile–seabed–wave interaction. If the influence of this interaction is not correctly understood during the design and construction of monopile structures, it can lead to instability and/or failure of monopiles in later use. Therefore, an analysis of the coupling response characteristics of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves has become a core technical issue that marine engineers focus on in the process of designing monopile structures. This article focuses on the coupling response characteristics of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions throughout the entire life cycle of the structure.

Many scholars studying offshore structures have conducted research using analytical solutions, numerical simulations, and physical model experiments to study the coupled dynamic response of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves. Some scholars have regarded waves and porous seabed as a coupled system and used the analytical solution method to study wave-seabed coupling3,4,5,6,7. However, analytical methods are limited to situations with relatively simple boundary conditions and are not applicable to situations involving structures. So, the current research results on the coupling response characteristics of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves mainly rely on numerical simulation and physical model experiments.

At present, numerical simulation methods are becoming more mature with the development of computer technology8. They have the advantages of simple equipment requirements, low costs, and the ability to achieve full-scale simulation. They have become an important method for studying coupling response characteristics of offshore monopiles, sea, and waves. Jeng, et al.9,10,11 developed numerical simulation software (FSSI-CAS-2D/3D) for studying fluid seabed structure interactions by coupling Navier–Stokes equations and Biot dynamic equations. The reliability and applicability of the model were verified using existing analytical solutions and wave tank experiments, and it was successfully applied to the study of wave structure–seabed interaction problems under different conditions. Chang and Jeng8 used COMSOL software to study the wave stability of wind turbine pile foundations and seabed foundations in the East China Sea. Zhang, et al.12 discussed the influence of seabed heterogeneity on the wave impact dynamic response of a seabed foundation near monopile foundation based on the VARANS equation and the fully dynamic response “u-w” equation. Sui, et al.13 used computational fluid software FUNWAVE 2.0 to simulate wave motion, and then used the fully dynamic response “u-w” equation as the control equation to study the coupling response of waves and seabed beside a monopile. They analyzed the effects of permeability coefficient, saturation, and wavelength on the wave response of the seabed. Sui, et al.14 further studied the consolidation process and wave dynamic response of the seabed around a monopile foundation, and considered the influence of the consolidation state on the transient liquefaction depth of the seabed.

Tong, et al.15 proposed a numerical model to analyze the wave–monopile–seabed coupling effect considering nonlinear contact at the pile–soil interface. Zhao, et al.16 studied the cumulative liquefaction of a seabed foundation around piles caused by waves using COMOSL software. Zhang, et al.17 studied the wave dynamic response of a group of four piles and a seabed foundation. Iqbal, et al.18 conducted experiment and numerical method study to investigate monopile–soil behavior under waves respectively. Zeng, et al.19 introduced a constitutive model to reflect the cementation damage behavior of cement soil to investigate its effects on the soil and the horizontal bearing capacity of a monopile. Zhang, et al.20 established a numerical method by coupling the computational fluid dynamic (CFD) and the discrete element method (DEM) in order to study the local scour around a monopile. Shi, et al.21 studied the effects of higher harmonic wave loads and wave runup on an offshore wind turbine under extreme wave conditions by numerical simulation.

Although above simulation methods are relatively mature and can describe the motion process of the breaking, reflection, and superposition of waves after colliding with monopile, determine the wave impact force on the surface of the monopile, provide feedback on the changes in seabed pore water pressure caused by waves, and consider the wave energy change because of the interaction between pore water and pore media, there are shortcomings: the seabed does not deform under wave forces, so the influence of seabed deformation on wave propagation cannot be considered, and the deformation of the seabed also does not feedback to waves. When offshore monopiles are constructed, would form a complex flow–structure–seabed coupling response22. Some researchers realized that the multi-scale nested or coupled simulation method would be better for discussing that complex coupled response problems23,24,25.

Physical model experiments are also an important method for studying this problem. Sleath26 through a water tank test, first discovered the phenomenon of the pore water pressure changed caused by waves in the seabed soil. Tsai, et al.27 conducted large-scale fluid structure coupling water tank experiments, and found that the pore water pressure gradient caused by waves makes sandy seabed more susceptible to erosion at the trough position. Bachynski, et al.28 and Buljac, et al.29 conducted experimental method to investigate the responses of an offshore monopile wind turbine subjected to irregular wave loads. Lyu, et al.30 and Zhang, et al.31 studied the local scour and the effect to monopile using experiment method, and find the effects of offshore wind turbines subjected to wind, waves, and currents. Zhu, et al.32 and Yu, et al.33 investigated the effects of waves to monopile in a wave flume, and studied the pore water pressure response law around monopile. Cheng, et al.34 used colored tracer sand to study the rule of sediment movement around a monopile.

Previous studies on the coupled response characteristics of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves have raised the level of designing offshore monopile structures. The research on the coupling response characteristics of off-shore monopiles, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions has not been reported, which is important to the safety of the entire life cycle of monopiles. Based on the above background and issues, this article aims to investigate the coupling response of offshore monopile and seabed under waves in various sea conditions. To achieve this goal, the structure of this paper is arranged as follows:

-

Chapter 1: Literature Review. This chapter will comprehensively review existing literature related to this study. Many scholars studying offshore structures have conducted research using analytical solutions, numerical simulations, and physical model experiments to study the coupled dynamic response of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves. Previous studies on the coupled response characteristics of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves have raised the level of designing offshore monopile structures. The research on the coupling response characteristics of off-shore monopiles, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions has not been reported.

-

Chapter 2: Experimental Design. This chapter will provide a detailed introduction to the experimental design of the offshore monopile in the wave flume, data collection and analysis techniques, experimental process, and experimental conditions used in this study. This experiment had comprehensively reflect the dynamic characteristics.

-

Chapter 3: Experiment Results. This chapter presented the results of the experiment and elaborate on the dynamic response of the monopile under different wave actions, including wave pressure, pore pressure, motion response, analysis of monocular stationary, etc., through charts and time history curves.

-

Chapter 4: Discussion. This chapter provided an in-depth discussion of the experimental results, including monopile stability control analysis, pile–soil interaction model under long-term wave action, coupling effect between monopile, seabed foundation, and waves.

-

Chapter 5: Conclusions. This chapter summarized the main findings and contributions of the entire text, provided insights for the design of offshore monopiles in the face of various marine environmental challenges.

Experimental design

Experimental model

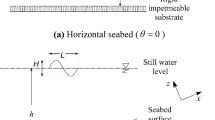

Figure 1 shows the overall layout of the offshore monopile in the wave flume, which simulated the dynamic response of an offshore monopile under the impact of waves. The flume used in the model experiment is the same as previous experiments35. The basic physical parameters of the soil for experiment are listed in Table 1.

Based on the results of previous investigations of flume experiments35, the geometric scale of the model in this test was determined as l = 1:24. The corresponding parameters between the prototype and the experimental model according to the gravity similarity principle are presented in Table 2.

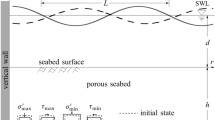

The monopile model made for this experiment (shown in Fig. 2a) was used to investigate the coupling response between the monopile and seabed foundation under the impact of waves in various sea conditions. Figure 2b shows the arrangement of pore pressure sensors in the seabed. The diameter of the pile was 0.2 m, the depth of pile embedded in the seabed foundation was 0.3 m, and the part above the mud surface was 0.7 m. The offshore monopile was made of plexiglas as previous investigations of flume experiments35.

The performance of the testing instruments and the manufacturer are consistent with previous flume experiments35, and the accuracy of the measurement of the devices used in the experiment is as follows: wave measurement devices (measurement range 0.60 m, accuracy ± 1 mm, sampling frequency 500 Hz); wave pressure sensors (measurement range 10 kPa, accuracy ± 0.01 kPa, sampling frequency 500 kHz); motion tracking devices (measurement distance 0.30 m, accuracy ± 0.1 mm, sampling frequency 500 Hz); accelerometer (three-axis acceleration, measurement range 1 g, lateral sensitivity ≤ ± 5%, sampling frequency 400 Hz); pore pressure sensors (measurement range 100 kPa, accuracy ± 0.01 kPa, sampling frequency 100 Hz). The locations of all of the instruments are presented in Fig. 2(Figure 2a was the schematic diagram of sensor layout; Fig. 2b was arrangement of pore pressure sensors). Six pressure sensors were installed on the wave-facing side of the pile (E1–E6), and the other six were installed on side face of the pile (E7–E12). An acceleration sensor was installed on the upper pile (A1). A 6-DOF motion displacement testing instrument was installed on the top of the pile (L1); Three wave-height sensors were installed to measure the wave surface change process inside the flume(WH1–WH3); Four pore pressure sensors were installed at 0.05 m on the front of monopile (P5–P8), the other four were installed at back side of the monopile (P9–P12), and the last four were installed at 1.05 m in front of the monopile model (P1–P4).

Experimental procedure

The experimental procedure was carried out as follows35:

-

(1)

Rinse the wave flume with clean water.

-

(2)

Build seabed models layer by layer, with each layer thickness not exceeding 10 cm. Place the monopile model and all measuring instruments. (Fig. 2).

-

(3)

Connect all measuring instruments and perform calibration (Fig. 3).

-

(4)

Add water to the flume, saturation more than 24 h to ensure that the soil of foundation is complete saturated.

-

(5)

Calibrate waves parameters, place three wave height meters at the set positions and compare the test spectrum of the waves with the theoretical spectrum.

-

(6)

Start the flume experiment as Table 3.

Experimental conditions

The experimental conditions are summarized in Table 3. The wavelength (\(\:{L}_{w}\)) and wave celerity (\(\:C\)) were calculated as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively35:

Experiment results

Simulation of test waves

Based on the widely adopted JONSWAP spectrum36 as the target input spectrum, physical simulation of irregular waves was carried out in the flume experiment that meet the requirements, and the target parameter requirements were achieved at the designated experimental position. The simulation test of waves was carried out before the formal experiment according to the experimental conditions in Table 3. Three wave height meters have been placed in the spectrum, as shown in Fig. 2, and the wave front process was measured. During wave spectrum simulation, the total energy deviation is controlled at 10%, and the deviation between the wave height (Hs) and the wave period (T) were controlled at 5%. Irregular waves were simulated using effective wave height and spectral peak period as control conditions, with the time of a single wave condition was controlled at around 900 ~ 1400 s. Figure 4a showed the simulation result of a typical irregular wave process, and Fig. 4b showed the comparison between the typical irregular wave’s spectrum and the theoretical spectrum. It can be seen that the measured spectrum and the target spectrum match well.

Wave pressure

The experiment results of wave pressure dynamic response of the monopile under the force of waves are shown in Fig. 5, which shows the results of analyzing and comparing the monopile under waves in various sea conditions.

The wave pressure on the wave face of the monopile increased as the height of position of the waves on the monopile leg increased, as shown in Fig. 5a. As the wave height increased, the wave pressure increased. Different water depths have different response to wave pressure on wave surface of monopile. When the water depth was 41.7 cm, the largest wave pressure measured at point E4 (\(\:{H}_{s}\) ≤ 12.5 cm) and point E5 (\(\:{H}_{s}\) = 18.6 cm) and its height was 40 cm and 50 cm respectively. When the water depth was 50 cm, the largest wave pressure measured at point E5, and its height was 50 cm. However, when the water depth was 62.5 cm, the height of the largest wave pressure measured (point E6) was 60 cm, the same height as the surface of wave.

By comparing the analysis results in Fig. 5a and b, we can see that the wave pressure was overall less on the side of the monopile relative to the wave face than on the wave face. As shown in Fig. 5b, the depth of the water had a different response on the wave pressure on the side face of the monopile relative to the wave face: when the water depth was 41.7 cm, the height of the largest wave pressure measured at point E9 was 40 cm, and when the water depth was greater than or equal to 50 cm, the monopile top was submerged, and the wave pressure changed basically along the height of the monopile leg.

Figure 6a and b shows the wave pressure history of the monopile under the impact of waves (\(\:{h}_{w}\) = 50.0 cm; \(\:{H}_{s}\) = 23.3 cm; T = 2.04 s). The largest wave pressure at point E4 of the monopile was 1.39 kPa, which is 0.36 kPa greater than that of point E10, the height relative to the wave surface is the same as the side of monopile.

Pore pressure

The pore pressure under the impact of waves decreased as the depth increased, but increased as the wave height increased, which was discovered in previous literature20,25,35. However, the test results in this paper yielded some meaningful findings regarding the situation under waves in various sea conditions, which need to be further investigated.

When the height of the wave is low, the wave has little influence on the pore water pressure of the foundation bed, and the pore water pressure at each point is basically equal to the corresponding depth pressure under static water conditions, showing no obvious cumulative rise. As shown in Fig. 7, this phenomenon was observed at four monitoring points (P1–P4) at a distance of 1.05 m in front of the pile and eight monitoring points (P5–P12) at a distance of 0.5 m around the pile.

Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the time history curves of pore water pressure at seabed monitoring points under the action of two kinds of waves when the height of the wave was large (\(\:{h}_{w}\) = 50 cm; Hs = 23.3 cm; T = 2.04 s; \(\:{h}_{w}\) = 62.5 cm; Hs = 30.0 cm; T = 2.45 s). They show the following: First, as shown in Figs. 8a and 9a, the pore water pressure time history curves of the four monitoring points (P1–P4) at a distance of 1.05 m in front of the pile indicate that there was a significant increase in pore water pressure at monitoring point P1 with a burial depth of 0.05 m, and as the depth of the monitoring points increased, the increase in pore water pressure weakened, and the increase in pore water pressure at monitoring point P4 was the least significant. On an unstructured seabed, the pore water pressure decreases with increasing depth due to the influence of waves, and the influence rapidly decreases with increasing depth. Second, regarding the pore pressure of measuring points around the monopile model (P5–P12), the dynamic pore water pressure first decreased and then increased along the depth direction. As shown in Figs. 8b and 9b, the pore water pressure time history curves of the four monitoring points (P5–P8) located 0.05 m in front of the pile indicate that the monitoring points with severely increased pore water pressure were P7 and P8, with depths of 0.25 and 0.35 m, respectively. On the contrary, P5 and P6, which were shallower and more affected by waves, had a smaller increase in pore water pressure than P7 and P8. As shown in Figs. 8c and 9c, the pore water pressure time history curves of the four monitoring points located 0.05 m behind the pile (P9–P12) indicate the same phenomenon of rising pore water pressure as in front of the pile.

The above phenomenon reveals the coupling effect of waves on a monopile seabed, and there are significant differences in the coupling effect under various sea conditions. When waves are large enough, the dynamic pore water pressure around the monopile first decreases and then increases along the depth direction. There may be two reasons for this: first, the bottom of the seabed is an impermeable boundary, which hinders the infiltration of water in the seabeds, and second, the wave impact on the monopile vibrates and squeezes the soil near the pile leg, and the closer the pile bottom, the more intense the squeeze. Therefore, there was an increasing trend of dynamic pore pressure amplitude.

The attenuation of dynamic pore pressure amplitude is due to the drag force generated by friction waves and soil particles in the porous seabed during the flow process, which hinders the flow of fluid and leads to decreased dynamic pore pressure amplitude.

Motion response

The motion of the model monopile under waves included surg, pitching, and heaving, as shown in Fig. 10, where the rolling is perpendicular to pitching. As shown in Fig. 11, the most intense motion type of the model monopile under waves was surging, followed by rolling, and the least obvious motion phenomenon was heaving, which was almost non-existent. When the height of the wave increased to 23.3 cm, the platform’s almost motion was surging (along the wave propagation direction), due to the wave impact, and the second motion type was rolling. Thus, we can see that the movement of a monopile is mainly affected by the height of the waves.

Analysis of monopile stationary

Based on the above experimental results, including wave pressure, pore pressure, motion response, the steady-state of the monopile was discussed. When the wave height was small, the model monopile did not show significant movement. However, as the wave height increased, when the water depth was not less than 41.7 cm and the wave height was not less than 18.6 cm, the impact of wave impact was significant, and there was obvious shaking, and the model monopile was no longer stationary.

Discussion

Monopile stability control analysis

The analysis of the stability of the monopile reveals the following: (a) In wave conditions of \(\:{h}_{w}\) = 41.7 cm, Hs = 12.5 cm, and T = 1.63 s, the pile leg basically does not move, the overall stability is maintained, the maximum longitudinal movement (monopile’s top displacement along the wave propagation direction) under the corresponding working condition is 0.11 cm, the pile length is 1 m, and the ratio of longitudinal movement to the pile leg length is \(\:1.1\times\:{10}^{-3}\). (b) In wave conditions of \(\:{h}_{w}\) = 41.7 cm, Hs = 18.6 cm, and T = 1.63 s, the pile leg is stable. The maximum longitudinal movement under the corresponding working condition is 1.83 cm, and the ratio between longitudinal movement and pile leg length is \(\:1.83\times\:{10}^{-2}\). (c) In wave conditions of \(\:{h}_{w}\) = 50 cm, Hs = 23.3 cm, and T = 2.04 s, the pile leg is unstable and causes obvious shaking, and at this time, the maximum longitudinal movement under the corresponding working condition is 2.67 cm, and the ratio between longitudinal movement and pile leg length is \(\:2.67\times\:{10}^{-2}\).

According to the analysis of the experiment results, we suggest that the ratio of maximum longitudinal displacement to pile length can be considered as the stability control standard for offshore monopiles in feasibility study and demonstration of offshore wind power engineering:

where \(\:U\:\)is the maximum longitudinal movement of the monopile, H is the length of the monopile, and\(\:\:\left[\theta\:\right]\:\:\)is the standard ration for monopile stability control, which is recommended to be \(\:2.00\times\:{10}^{-2}\).

The flume test in this paper also revealed that the internal reason for the instability of the monopile under the impact action of waves was the oscillating pore pressure around the monopile under the action of wave cyclic load, which causes seabed liquefaction, that is, transient liquefaction. The mechanism is wave propagation in the porous seabed producing drag force, which will block wave propagation and attenuate wave emission, while waves do not attenuate in the fluid domain. This creates a phase difference, causing the seabed to liquefy. The pore water pressure oscillates violently under the action of waves, which is manifested by a rapid change of soil displacement around the monopile. The soil displacement around the monopile under the action of waves can also be used as a stability control index of monopiles in shallow seas.

Pile–soil interaction model under long-term wave action

The pile–soil interaction model under long-term wave action is considered in pile design; especially in soft soil, the API standard P-Y model is generally recommended37. In the API standard, the soil reaction subjected to the pile is divided into axial and lateral; the axial soil reaction includes the axial transfer load reaction and the load reaction at the end of the pile. The stiffness of the horizontal spring is determined by P-Y. The vertical spring stiffness is determined by a t-Z curve, and the end spring is determined by a Q-Z curve. According to the above method, the horizontal load of the pile can be given by combining the recommended P-Y curve37. However, when the method is applied to get the horizontal load of a monopile under long-term wave action, the liquefaction of soil around the monopile under potentially extreme wave action cannot be ignored.

In the flume test in this study, the model monopile moved and shook under waves with height more than 18.6 cm, and with increased wave height and period, the pile movement was more obvious, squeezing the nearby soil and causing a gradual rise in pore water pressure around the monopile; when the wave impact was strong enough, it resulted in insufficient horizontal bearing capacity of the seabed around the monopile, and the monopile lost stability38. In this case, it is very dangerous to use the API-specified P-Y model to determine the horizontal load of the pile. This is also the reason why pile accidents at sea cannot be ignored. It is suggested that the scientific method should be used to analyze the possible liquefaction of soil around monopiles under long-term wave action in various sea conditions. It is suggested to accomplish that work before using the API-specified P-Y model to analyze the interaction problem of offshore monopile, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions. This is where the scientific question of this paper comes in.

Coupling effect between monopile, seabed foundation, and waves

At present, when studying the coupling effect between a monopile, the seabed foundation, and waves, most research only considers the shock response of the seabed under wave action, the influence of the pile on waves, and the influence of sea bed liquefaction around the pile. The influence of the seabed on waves is generally ignored in experiments and numerical simulations, also the influence of the upper structure (such as wind turbines) or wind was not considered, and we will consider adding the influence of the upper structure or wind in future research. However, it can be confirmed that the effect of the upper structure or wind will increase the Coupling Effect between Monociles, Seabed Foundation, and Waves.

It should be pointed out that the dynamic response of the monopile in a shallow sea area is not affected by the dynamic conditions under the action of waves. In addition to the influence of factors such as the shape and scale of the structure, it is also affected by the soil conditions of the seabed around the monopile, such as the dry density of soil, clay content, and other parameters; according to the dry density and clay content, it is mainly divided into sandy soil, silt soil, silty sand, and silt soil. Due to the limitations of the test conditions, the soil sample used in this paper was taken from the bottom of Bohai Bay, and according to the screening test, it was determined to be silty clay. The dry density of the seabed foundation of the test model was 1.502\(\:\:g/{cm}^{3}\), and the seabed of the model was in a relatively dense state as a whole. Therefore, the test results obtained in this study are mainly applicable to silt clay seabed. For other types of seabed, such as sandy soil, silty soil, and silty soil, the results of this study still have certain reference values, and relevant experiments will be added in the future to discuss the effect of different types of soil in the seabed to the coupling effect between the monopile, seabed foundation, and waves.

Conclusions

In this paper, we carried out an experimental analysis of a monopile under waves in various sea conditions and investigated the coupling response of the monopile seabed, and waves, along with the coupling between the monopile and the seabed foundation, providing insights for the design of offshore monopiles in the face of various marine environmental challenges. The main conclusions are as follows:

The wave pressure on the monopile increased with increasing wave height, and increased with the position height of the monopile, and the water pressure was greater on the front face of the monopile than on the side face. The wave pressure on the monopile at the same height as the sea level is the largest at a lower water level; when the top of the monopile is submerged at a high-water level, the wave pressure changes little along the height of the pile.

Under the action of waves, the monopile leg was affected by the wave impact, and the monopile began to move; with increasing wave height and period, the pile movement was more obvious, squeezing the soil near the monopile and causing the surrounding pore water pressure to rise gradually; when the wave impact was strong enough, the monopile lost stability.

A wave fume test was carried out to study the distribution of pore water pressure around the monopile under wave action, which revealed a significant difference in the coupling response characteristics of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions. When the height of the waves was small, the coupling response characteristics of the offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves were not obvious, and the pore water pressure attenuated quickly in the direction of the depth of the seabed. With increased height and period of waves, when the test wave height was more than 18.6 cm the period was more than 1.63 s, and the monitoring points were at a certain distance from the monopile, the pore water pressure attenuated in the direction of the depth of the coastal bed; however, the dynamic pore water pressure around the monopile first decreased and then increased along the depth direction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Haiderali, A. E., Madabhushi, G. S. P. & Nakashima, M. Numerical investigation of monopiles in structured clay under cyclic loading. Ocean. Eng. 289 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116181 (2023).

Damiani, R., Ning, A., Maples, B., Smith, A. & Dykes, K. Scenario analysis for techno-economic model development of U.S. offshore wind support structures. Wind Energy. 20, 731–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/we.2021 (2017).

Lee, T. C., Tsai, C. P. & Jeng, D. S. Ocean waves propagating over a porous seabed of finite thickness. Ocean. Eng. 29, 1577–1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-8018(01)00078-6 (2002).

Lee, T. L., Tsai, C. P. & Jeng, D. S. Ocean waves propagating over a Coulomb-damped poroelastic seabed of finite thickness: An analytical solution. Comput. Geotech. 29, 119–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-352X(01)00024-6 (2002).

Lin, M. & Jeng, D. S. A 3-D model for ocean waves over a Columb-damping poroelastic seabed. Ocean. Eng. 31, 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2003.10.001 (2004).

Chen, C. Y. & Hsu, J. R. C. Interaction between internal waves and a permeable seabed. Ocean. Eng. 32, 587–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2004.08.010 (2005).

Hsieh, P. C. A viscoelastic model for the dynamic response of soils to periodical surface water disturbance. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 30, 1201–1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.519 (2006).

Chang, K. T. & Jeng, D. S. Numerical study for wave-induced seabed response around offshore wind turbine foundation in Donghai offshore wind farm, Shanghai, China. Ocean. Eng. 85, 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2014.04.020 (2014).

Jeng, D., Ye, J., Zhang, J. & Liu, P. L. F. An integrated model for the wave-induced seabed response around marine structures: Model verifications and applications. Coastal. Eng. 72, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COASTALENG.2012.08.006 (2013).

Ye, J., Jeng, D., Wang, R. H. & Changqi, Z. A 3-D semi-coupled numerical model for fluid–structures–seabed-interaction (FSSI-CAS 3D): Model and verification. J. Fluids Struct. 40, 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFLUIDSTRUCTS.2013.03.017 (2013).

Ye, J., Jeng, D., Wang, R. H. & Zhu, C. Validation of a 2-D semi-coupled numerical model for fluid–structure–seabed interaction. J. Fluids Struct. 42, 333–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFLUIDSTRUCTS.2013.04.008 (2013).

Zhang, C., Sui, T., Zheng, J., Xie, M. & Nguyen, V. T. Modelling wave-induced 3D non-homogeneous seabed response. Appl. Ocean. Res. 61, 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2016.10.008 (2016).

Sui, T. et al. Three-dimensional numerical model for wave-induced seabed response around mono-pile. Ships Offshore Struct. 11, 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445302.2015.1051312 (2015).

Sui, T. et al. Consolidation of unsaturated seabed around an inserted pile foundation and its effects on the wave-induced momentary liquefaction. Ocean. Eng. 131, 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.10.019 (2017).

Tong, D., Liao, C. & Chen, J. Wave-monopile-seabed interaction considering nonlinear pile-soil contact. Comput. Geotech. 113 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.04.021 (2019).

Zhao, H. Y., Jeng, D. S., Liao, C. C. & Zhu, J. F. Three-dimensional modeling of wave-induced residual seabed response around a mono-pile foundation. Coastal. Eng. 128, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2017.07.002 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Zhou, X. L., Wang, J. H. & Guo, J. J. Wave-induced seabed response around an offshore pile foundation platform. Ocean. Eng. 130, 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.12.016 (2017).

Iqbal, K. et al. Numerical assessment of offshore monopile-soil interface subjected to different pile configurations and soil features of arabian sea in a frequency domain. Appl. Ocean. Res. 118 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2021.102969 (2022).

Zeng, B. et al. Numerical simulation of horizontal bearing characteristics of cement-soil reinforced rock-socketed steel pipe monopile considering cementation damage. Comput. Geotech. 162 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105626 (2023).

Zhang, S., Li, B. & Ma, H. Numerical investigation of scour around the monopile using CFD-DEM coupling method. Coastal. Eng. 183 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2023.104334 (2023).

Shi, W., Zeng, X., Feng, X., Shao, Y. & Li, X. Numerical study of higher-harmonic wave loads and runup on monopiles with and without ice-breaking cones based on a phase-inversion method. Ocean. Eng. 267 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.113221 (2023).

Lin, Z. et al. Investigation of nonlinear wave-induced seabed response around mono-pile foundation. Coastal. Eng. 121, 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2017.01.002 (2017).

Schinnerl, M., Schöberl, J. & Kaltenbacher, M. Nested multigrid methods for the fast numerical computation of 3D magnetic fields. IEEE Trans. Magn. 36, 1553–1556. https://doi.org/10.1109/20.877736 (2000).

Yu, F. & Zhang, Z. Implementation and application of a nested numerical storm surge forecast model in the East China Sea. Acta Oceanolog Sin. 21, 19–31 (2002).

Zhang, J., Wang, F., Guo, Y., Chen, H. & Zhang, Q. Nested numerical simulation of multi-scale flow characteristics around monopile foundation of offshore wind farm at Weihai coastal water, China. Ocean. Eng. 288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116171 (2023).

Sleath, J. F. A. Wave-Induced pressures in beds of sand. J. Hydraulics Div. 96, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1061/JYCEAJ.0002325 (1970).

Tsai, C. P., Lee, T. L. & Hsu, J. R. C. Effect of wave non-linearity on the standing-wave-induced seabed response. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 24, 869–892 (2000).

Bachynski, E., Thys, M. & Delhaye, V. Dynamic response of a monopile wind turbine in waves: Experimental uncertainty analysis for validation of numerical tools. Appl. Ocean. Res. 89, 96–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2019.05.002 (2019).

Buljac, A., Kozmar, H., Yang, W. & Kareem, A. Concurrent wind, wave and current loads on a monopile-supported offshore wind turbine. Eng. Struct. 255 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.113950 (2022).

Lyu, X., Cheng, Y., Wang, W., An, H. & Li, Y. Experimental study on local scour around submerged monopile under combined waves and current. Ocean. Eng. 240 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109929 (2021).

Zhang, B. et al. Experimental study on dynamic characteristics of a monopile foundation based on local scour in combined waves and current. Ocean. Eng. 266 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.113003 (2022).

Zhu, J., Gao, Y., Wang, L. & Li, W. Experimental investigation of breaking regular and irregular waves slamming on an offshore monopile wind turbine. Mar. Struct. 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2022.103270 (2022).

Yu, Z., Cheng, Y. & Cheng, H. Experimental investigation on seabed response characteristics considering vibration effect of offshore monopile foundation. Ocean. Eng. 288 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116000 (2023).

Cheng, Y., Xie, H., Zheng, Y. & Shi, L. Experimental study on the sediment movement around monopile under vibration action. Ocean. Eng. 288 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116206 (2023).

Ye, H., Zu, F., Jiang, C., Bai, W. & Fan, Y. Experimental investigation of the coupling effect of jackup offshore platforms, towers, and seabed foundations under waves of large wave height. Water. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/w15010024 (2022).

Goda, Y. A comparative review on the functional forms of directional wave spectrum. Coastal. Eng. J. 41, 1–20 https://doi.org/10.1142/S0578563499000024 (1999).

Institute, A. P. Recommended Practice for Planning, Designing, and Constructing Fixed Offshore Platforms-Working Stress Design: Upstream Segment. API Recommended Practice 2A-WSD (RP 2A-WSD): Errata and Supplement 1, December 2002 (American Petroleum Institute, 2000).

Tsai, C. C., Li, Y. P. & Lin, S. H. p-y based approach to predicting the response of monopile embedded in soft clay under long-term cyclic loading. Ocean. Eng. 275 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.114144 (2023).

Funding

Not founding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y.; methodology, H.Y.; software, H.Y.; validation, W.B., and H.Y.; resources, Y.F.; data curation, W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. and Y.F.; visualization, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, H., Fan, Y., Bai, W. et al. Experimental study of coupling response characteristics of offshore monopiles, seabed, and waves in various sea conditions. Sci Rep 14, 28560 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79858-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79858-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on oscillation effect of wind power pile foundation on local scour

Scientific Reports (2025)