Abstract

Children in Mongolia are exposed to harmful levels of household air pollution (HAP) due to a high reliance on coal for indoor cooking and heating. This study aims to assess the association between HAP and child health outcomes, in a birth cohort from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. A composite HAP measure was created using information on cooking and heating fuels and behaviours collected as part of a randomised control trial assessing the impact of swaddling on child health. Child health outcomes (Bayley Scales of Infant Development scores [BSID-II], pneumonia, height and weight) were collected at 7, 13, and 36 months. Linear and Cox proportional hazard model were used to assess the association between HAP and child health outcomes at each time point, adjusting for child, maternal and environmental confounding factors. An increased risk of pneumonia was observed with an increasing HAP score (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.02 [1.01, 1.04]) at 7 months). An increase in HAP exposure was associated with a decrease in the BSID mental score at 13 months (β: − 0.09 [− 0.17, − 0.01]), BSID psychomotor score at 36 months (β: − 0.12 [− 0.23, − 0.02]). A decrease in height-for-age z-score (HAZ) and weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) were associated with increased HAP exposure at 7 (HAZ β: − 0.019 [− 0.030, − 0.010] and 13 months (HAZ β: − 0.020 [− 0.030, − 0.011], and WAZ β: − 0.012 [− 0.019, − 0.005]), however only HAZ was associated with HAP at 36 months (β: − 0.011 [− 0.020, − 0.002]). An increasing HAP score was associated with an increase in the health outcome composite score at 7 months only (β: 0.019; 95% CI 0.003–0.035). HAP exposure was shown to negatively impact child health sustainably over 3 years. There are implications for development of appropriate public health policies to mitigate HAP exposure throughout Mongolia and similar Central Asia settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Household air pollution (HAP) from cooking, heating and lighting using solid biomass fuel (wood, dung, charcoal, and crop residue) and coal, causes significant morbidity and mortality and is a global public health concern in low- and middle-income countries (LIMCs)1. Evidence on the impact of air pollution on health is still expanding. Based on the current evidence, globally there are 3.8 million premature deaths2 and 110 million disability-adjusted life years attributable to HAP each year3, with health events associated with HAP occurring through the life course4. Women and children are particularly vulnerable to HAP due to often spending a greater amount of time within the home than other household members5. In addition, the immature physiology of children increases their vulnerability to HAP6. Health events associated with HAP occur with pregnancy (e.g., low-birthweight, pre-term birth, preeclampsia)7 and continue into childhood (e.g., acute respiratory infection (ARI), asthma, burns, neurodevelopmental disorders, stunting)8,9 and adulthood, (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], cardiovascular disease, cognition)2,10,11,12. However, studies that investigate the health implications of HAP exposure are often cross-sectional or experimental in nature13 and lack longitudinally8. Few studies use birth cohorts to investigate child health impacts from HAP in LIMCs, but those that have done so only investigated health events in the first14, second15 and fourth year of life16. In addition, there is a paucity of evidence in the literature around the use of composite health outcome measures, for multiple health outcomes. There are also environmental (e.g., landslide, erosion etc.)17,18 and socioeconomic (e.g., opportunity costs, gender inequality, healthcare cost)5,19,20,21,22 implications associated with the reliance and exposure to HAP producing fuels.

Mongolia is a land-locked lower-middle-income country in north-central Asia, positioned on a plateau surrounded by high mountain ranges. The capital city of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, holds over half the population (1,900,000 people 2023) and often reaches temperatures of − 20 °C, resulting in heavy reliance on household heating to stay warm23. Mongolia has four seasons, winter (November-February), spring (March-May), summer (June-August) and autumn (September-October). Sixty-percent of the capital’s population live in the so-called ger districts surrounding the city, which comprise of both traditional Mongolian felt tents called gers and rudimentary wooden/brick houses. The vast majority of such households have a reliance on coal fired stoves for cooking and heating, burning approximately 3–6 tons of coal each winter, resulting in hazardous levels of indoor and outdoor air pollution24,25. The remaining 40% of the population live mainly in apartments, which have central heating23. In other parts of the country, as with many other surrounding Central Asian regions26, similar ger structures or wooden housing structures also have similar stoves and burn coal or wood with high indoor HAP exposure for the young in winters. Despite HAP being a health threat, the majority of research into air pollution in Ullaanbaatar focuses on ambient air pollution, as it is deemed to be the greater problem.

Characterising and documenting an accurate level of exposure is a challenge for epidemiological studies. Self-reported exposures or measurement of particulate matter (PM) and carbon monoxide (CO) are commonly collected to estimate HAP exposure. Direct methods of collection are time consuming and expensive, often limiting the sample size27,28. Fuel type, stove type, and cooking location have previously been used to assess relative differences in HAP exposure, providing large-scale results, but are limited by the availability of information and not all factors that affect HAP concentrations can be taken into account. The use of evidence-based composite measures of HAP exposures allows for multiple factors that influence HAP concentrations (e.g., ventilation, fuel type, stove type) to be taken into consideration, giving a potential more accurate estimation of HAP exposure. However, there is a paucity of evidence for the use of composite HAP measures to understand the associated health impacts.

Therefore, this study aims to address the gap in the literature through multiple objectives: (a) demonstrate the feasibility of the use of a composite survey based air pollution score to assess exposure (b) assess over the first three years of life, the score and association between HAP and (i) child development using the Bayley Test, (ii) hospital-confirmed pneumonia, (iii) stunting (height-for-age z-score [HAZ]) and being underweight (weight-for-age z-score [WAZ]), as well as a (iv) health outcome composite score, in a birth cohort from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A HAP score could be calculated for 1266 (99%) children, with no observed difference in baseline characteristics with those children without a score (n = 13; 1%). Of the included children 421 (33.3%) resided in the lowest polluted households, 293 (23.1%) in low polluted households, 217 (17.1%) in medium polluted household, and 335 (26.5%) in highly polluted households. There was an even split between males (50.4%) and females (49.1%) (Table 1). Mean mental and psychomotor BSID scores were 105.5 (10.6) and 100.0 (16.0) for children at 13-months and 92.4 (11.0) and 100.9 (11.3) for children at 36-months. Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) pneumonia was identified in 24.8% of infants in the 7-months following birth (Table 1). HAZ scores at 7-, 13-, and 36-months had median values of 0.27 (IQR: − 0.44–1.19), − 0.61 (IQR: − 1.29–0.16) and − 0.85 (IQR: − 1.52 – − 0.16) respectively. Whereas WAZ scores at 7-, 36-, and 36-months had median values of 0.62 (IQR: − 0.06–1.28), 0.22 (IQR: − 0.37–0.83), and 0.08 (IQR: − 0.46–0.56), respectively. The composite health outcome score was found to have a median score of 7 (IQR: 5–8) at 7-months, 10 (IQR: 8–12) at 13-months, and 10 (IQR: 9–12) at 36-months (Supplementary Appendix 1).

BSID-II

Both mental and psychomotor BSID scores were associated with HAP exposure at 13- and 36-months in the unadjusted analysis (Table 2). After adjusting for child, maternal, and environmental confounding factors, being exposed to higher levels of HAP was associated with lower mental BSID score at 13-months (β: − 0.09; 95% CI − 0.17, − 0.01) and lower psychomotor scores at 36-months (β: − 0.12; 95% CI − 0.23, − 0.02). The same decrease with BSID score for psychomotor at 13-months and mental at 36-months was observed but was not statically significant.

Pneumonia

When assessing the HAP score as a continuous variable, the hazard ratio for pneumonia increased by 2% (95% CI: 1, 4) for every increase in the HAP score (Table 3). This increase in the hazards ratio with higher HAP scores was also observed when assessing the HAP scores as a categorical variable. Low HAP score had a 52% (4-124) increase, medium HAP scores a 71% (15–154) increase and high HAP score of an 80% (25–159) increase in the hazards ratio of pneumonia compared to the lowest HAP score; with the hazard ratio increasing in size from low to high HAP scores.

Height for age (HAZ) and weight for age (WAZ)

In the adjusted analysis HAZ and WAZ were associated with the HAP score at all three timepoints (Table 4). After adjusting for confounders only HAZ at 7-months was observed to be associated with every increase in the HAP score lowering the HAZ score by − 0.019 (95% CI: − 0.030, − 0.010). The same effect was also observed at 13-months, after adjusting for confounding. At 36-months, only HAZ was associated with the HAP score, with a − 0.011 (95% CI: − 0.020, − 0.002) decreased in the HAZ score with every increase in the HAP score.

Composite health measure

At 7-months there was an observed association in the adjusted analysis with every increase in HAP score, increasing the combined health score (pneumonia, stunting, underweight) by 0.020 (95% CI 0.004–0.036) (Table 5). However, no association was observed between the HAP score and combined health score (BSID-II, stunting, underweight) at 13 (β: 0.021; 95% CI − 0.001, 0.042) or 36-months (β: − 0.001; 95% CI − 0.024, 0.023). A further analysis adjusting for a change of residence within the 36-month follow-up period had little impact on the association between HAP score and combined health score at 36-months (Supplementary Appendix 2).

Discussion

This novel study investigating the effect of HAP exposure on child health, using a Mongolian birth cohort, with a large follow-up period (36-months), utilises a unique approach to estimating the level of HAP exposure through a composite score of air pollution sources and behavioural factors. The results indicate that exposure to HAP negatively impact child health within this setting sustainably over a 3-year period. Therefore, there is evident need for interventions to reduce the level of HAP in Mongolia and similar settings across Central Asia, to improve child health, which will have implications for the sustainable development goal 3 (Good health and well-being). This evidence endorses the findings of other studies that multiple health outcomes are affected by air pollution, which we demonstrate in one birth cohort for the impact on development, pneumonia (the leading cause of death in LMIC young children), and growth (indicator for other health outcomes).

The impacts of HAP on child health are well documented within the literature29, including pneumonia8,30,31, stunting32, underweight33, and, child growth14; which correspond with the results of this study. However, the existing research on the negative effects of HAP exposure on child neurodevelopment is more limited34,35 to which our study contributes significantly by demonstrating a sustained effect using a highly sensitive BSII scores across time from 13-months to 36-months. This negative effect is also seen in children exposed to high levels of ambient air pollution who have lower child development scores36. In Ulaanbaatar specifically, a recent RCT identified a positive association between reduction in HAP exposure during pregnancy and child cognitive development37. The results of the present study are robustly adjusted for and have statistical significance, but it is not clear what the clinical significance would be, with the BSID score, HAZ, and WAZ, as the relatively low associated average reduction in the score at individual level may not change the overall health status of the individual child (e.g., cross over a threshold). On a population level however, even small improvements in the outcome could result in a shift in the curve, which may well be clinically significant for the population at large. There is a known biological mechanism for the effect on child health, with CO and PM, from both exposure during pregnancy and after birth7,29, along with critical exposure time point being identified for different health outcomes38,39,40,41. However, this study does not explore the difference or change of risk with health outcomes from 12 to 36 months and further research is required to understand the critical points of exposure on determining the occurrence of developmental changes or growth of children. There is evidence of pre-natal and early life exposure resulting in respiratory health consequences, within the first seven months, suggesting a high-risk period. Developmental effects persist across 13 and 36 months, however, at 36 months motor development can be seen to be more prominent, which could be explained by motor skills being likely to be more limited at 13 months. Furthermore, WAZ and HAZ also have sustained long term effects. Although further research is required to identify critical times windows for exposure and expression of health events, this study does indicate that HAP effects on child health is prominent from a young age, suggesting that this is a particularly vulnerable period for exposure to HAP.

It is significant to note that our study was conducted at a time when the ambient (outside) air pollution in Ulaanbaatar was not as high as it is now and there was less awareness of the health threats in Mongolia42. Over the past decade, increased rural to urban migration and rapid modern urbanisation have increased the capital’s resident’s exposure to air pollution, through emissions from low-income housing, motor vehicles and power plants25. Subsequently, children in Mongolia today are exposed to both indoor household and ambient air pollution indicating that the risk to children in Ulaanbaatar in recent years is many folds higher and likely has a much higher rate of effect than the rates and scores in this study37. Whilst as a result of a steady increase of the population’s air pollution exposure, there have been multiple local air pollution mitigation strategies implemented over the past decade, including the recent 2019 ban on raw coal, Ulaanbaatar’s residents continue to be exposed to both hazardous indoor and outdoor pollution levels43,44. Our findings are deemed to be invaluable for assessing temporal changes in air pollution exposure and its related impact on health in Ulaanbaatar, which in turn could improve our understanding on the effectiveness of such mitigation strategies. The focus in Mongolia, however, has not been on reducing HAP in household living outside of the city of Ulaanbaatar, while our study demonstrates that these millions of children in Mongolia living outside of Ulaanbaatar and in neighbouring Central Asia26 where housing resembles the situation in Mongolia remain at high risk of adverse health outcomes. Our results are relevant to all children and pregnant women exposed to air pollution due to the collection of biological data and use of robust methods for health outcomes measures (e.g., BSID-II). However, extended longitudinal (beyond 3 years) and life-course approaches need to be undertaken within these settings to understand the long-term heath effect and changing health risks.

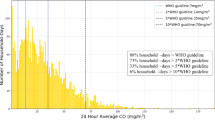

Another novel aspect of our study is in the methodological assessment of a new low-cost method of measuring HAP. The use of a composite measure of estimated HAP exposure, is an innovative technique and has enabled the quantification of multiple components that affect the HAP concentrations within a household. It is important to demonstrate evidence of validity of such a new method of HAP exposure estimation. We have achieved this through using published evidence45,46,47 on the importance of each component of the score and its effect on HAP, taking into consideration both sources of HAP (e.g., heating source, types of fuels, fuel condition48,49) and behaviours (e.g., stove use, fuel handling practices, opening of windows13,48,50,51) which influence HAP concentrations. We demonstrated a gradient between high and low exposure that can be seen within these analyses supporting the validity of the composite measure and the existing evidence that the continued reduction in HAP can lead to the potential for benefit with behavioural change (e.g., use of dry fuel, opening doors and windows etc.) in the short-term52. Although the use of a composite HAP score requires further validation, including comparisons to measured levels of air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, CO), it is a technique that can easily be deployed by adding further questions to suit any HAP exposure setting within a questionnaire beyond that of cooking/heating fuel types and location.

The health outcome composite score indicates that exposed children at 7-months may have multiple comorbidities as a result of HAP. No associations were observed at 13 or 36 months with the combined health score, however, due to the differing composition of the score these results cannot be directly compared to those at the 7-month time points. There is little evidence from the literature about multiple comorbidities in children due to exposure to HAP to compare the composite health score to and therefore any composite health score should be interpreted with caution53 and validated with further research. Having multiple health conditions associated with exposure to HAP, provides strong evidence for the need to reduce early childhood exposure and policymakers should investigate and consider the wider cost-benefits of HAP reduction in the context of multi-comorbidities.

Undertaking this largescale study on healthy children (i.e., not pre-term, no congenital abnormalities, not low birthweight etc.) may be seen as a limitation to its generalisability in that it excludes vulnerable predispositions such as very pre-mature or very-low birthweight or those with congenital malformations, but has reduced the uncertainties around predispose to events and that healthy children are being affect by HAP exposure. It is anticipated that there is potentially an increased risk of health events with HAP if children are already pre-disposed from birth and therefore our findings are an underestimate of effect that HAP would have at population level; showing the imperative need to develop action against HAP in Mongolia or similar settings to Ulaanbaatar in early 2000s. Further strengths of the study are demonstrated through the use of the WHO ICMI criteria and a large follow-up time. This long follow-up time, however, comes with the risk that household cooking and heating practices could have changed since their assessment at 7-months after birth, and may not be accurate at 36-months.

Furthermore, the composite health measure only indicates that multiple problems can occur as a results of HAP exposure, which provide useful evidence for policy makers. Finally, a strength is that due to all the births occurring within a four-month window (very end of autumn and whole of winter), the impact of season on the health events within this sample are likely to be minimal, apart from pneumonia, as events occurred within the 7-months post-birth. Further exploration would be required to investigate any potential differences if children were born within a different season, as in Ulaanbaatar the summers are warm and for three months there is little need for heating and the gers are more ventilated; even though cooking still takes place indoors with the same stoves.

Conclusion

Exposure to HAP within this birth cohort in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia was associated with negative health impacts for child health occurring from birth up to 36-months. Given the proportion of children and women exposed to HAP in Mongolia and the economic and social costs associated with growth retardation and respiratory diseases in children, these results could have significant public health implications and highlights the importance of measure to mitigate HAP exposure in all Mongolian populations and similar Central Asian countries with parallel housing setting. Further work should explore possible mechanisms for the longitudinal association of HAP and child development. In addition, if the HAP composite score is to validated, this could be an accessible method to assess these associations in other LMICs and globally, where indoor combustion of biomass for household energy is still common.

Methods

Study area, population and sampling strategy

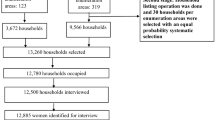

Data was collected as part of a three-stage RCT in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia in 2002, which was a large population-based study designed to investigate the effect of swaddling on child development in infants in Mongolia. Detailed documentation of the recruitment and follow-up are described elsewhere54,55,56, but in summary healthy infants delivered in four maternity hospitals in Ulaanbaatar, that manage over 95% of all births in the city, were recruited within 48 h of birth. Infants were excluded if born with a gestation < 36 weeks, a birthweight < 2500 g, severe congenital abnormalities needing special neonatal care, needing intensive care or resided in apartments that were kept too warm for the infant to be swaddled during the daytime. Ethical approval for the study was provided by Ministry of Health of Mongolia and the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and fully informed consent was obtained from the mothers. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Out of 4360 eligible births, 1279 infants were enrolled (Fig. 1), with a total of 1194 infants with pneumonia results at 7-months and BSID data being collected from 1100 infants at 13 months and 693 at 36 months. Except at 36 months, participants were lost to follow up due to refusal to participate, could not be found or had died. At 36 months, due to limited resources, the follow-up was all the families with post-natal depression, plus approximately three times a random sample of the remainder of the families.

Households air pollution exposure

In a ger household many factors influence the level of HAP present, therefore a weighted composition pollution score (Table 6) was created based on published literature on the effects of pollutant sources45,46,47 (e.g., heating source, cooking fuel, heating fuel, lighting fuel, fuel condition48,49) and behaviour57,58,59 (e.g., hours of stove use in 24 h, overnight use of stove, fuel handing practice, length time in 24 h that windows are open13,48,50,51) on HAP levels; where the higher the score the greater the level of HAP. Data on household cooking and heating practices were obtained at the 7-month follow-up, via a questionnaire. A corresponding score (Table 6) was given to each characteristic and multiple by the weight, to generate the weighted sum scores60. The weights were applied to each HAP factor, with pollutant determinants receiving a larger weighting (i.e., 2) than the behaviour determinants (i.e., 1) as these were perceived to be greater predictors of exposure. Missing values were estimated by taking the average of the total score of each respective variable in accordance with the mean substitution approach61,62. As apartments fully rely on heating provided by a central source rather than biomass stoves and cooking was not undertaken on biomass stoves, all apartments were assigned a HAP score of 0. The continuous composite HAP score was further categorised into four levels: lowest (score = 0), low (score < 18), medium (score 18–20), and high (score > 20).

Child health outcomes

Bayley scales of infant development scores (BSID-II)

The Bayley scales of infant development scores (BSID-II), a widely used and validated tool, was translated into Mongolian (including back-translation, piloting, and expert validation) and extensive training was provided to four child development health specialist professionals who conducted the tests. The BSID-II mental score included: children’s discriminations and response, sensory/perceptual acuity, vocalisation, and verbal communication initiation, memory learning and problem solving, foundations of abstract thinking, object constancy acquisition, complex language, mental mapping, mathematical concepts, and habit formation. Muscle coordination, degree of body control, dynamic movement, postural mimicry, fine manipulation abilities of the hands and fingers, and stereognosis (the ability to recognise objects by touch) are all assessed on the BSID-II psychomotor scale. Both scores are based on the infants reported age with a normed mean of 100 (SD: 15 points). For test-retest reliability, both scales show good correlation coefficients (0.83 and 0.77) for mental and psychomotor assessments63.

Pneumonia

Childhood pneumonia in children aged 0–7 months was detected through passive and active surveillance. Passive surveillance occurred through primary healthcare centres and hospitals, facilitated using child study ID cards and allocation of a family doctor linked to the study to attend when the child was unwell or the main children’s hospital in an emergency. Transport costs and antibiotics were provided by study as these are not part of the free service provision. Active surveillance occurred during follow-up home-visits through mother’s questionnaires obtaining information on any illnesses since the last visit, their nature and visits to doctor/hospital.

The Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) pneumonia definition was used, as it is compared to other studies64,65,66 and is more sensitive (less specific) that other definitions. All trial physicians were re-trained in the IMCI definitions for the purpose of the study. Pulse oximetry and a chest x-ray (undertaken by WHO-trained study radiographers) were undertaken on infants with signs of ‘very severe’ and severe’ pneumonia as differing by the IMCI criteria64,65,66.

Height and weight z-scores

Height (cm) and weight (kg) were obtained by trained fieldworkers at 7-, 13-, and 36-months to calculate height-for-age (HAZ) and weight-for-age (WAZ) z-scores based on the WHO classification67.

Composite health outcome measure

An exploratory composite health score based on the available health outcomes at each of the three time points (7-, 13-, and 36-months) was created to give an indication of the occurrence of multiple health problems associated with HAP exposure. An additional composite score (Table 7) was created based on the occurrence of disease for categorical outcomes and quartiles for continues outcomes. The greater the score the more health events the child experienced, with a maximum score of 10 for 7-months and a maximum score of 16 for both 13- and 36-month timepoints.

Covariates

Child, maternal and environmental confounding factors were considered for analysis, which were all modelled as categorical variables; apart form date of birth which was modelled as a continuous variable. Details of the confounders can be found in Table 1.

Statistical methods

All data cleaning was undertaken in Microsoft Excel68 and analysis in STATA version 1769. Descriptive statistic included number of observation (n) and percentage (%) for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed continuous variables. To assess the association between HAP and child health outcomes (BSID, pneumonia, HAZ, WAZ, composite health measure) multivariate generalised linear models were used. Covariates were a priori identified, with a hierarchical approach taken to build up the model, starting with child factors, followed by maternal factors and then environmental factors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Smith, K. R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: recommendations for research. Indoor Air 12, 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01137.x (2002).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines (2021).

Smith, K. R. et al. Millions dead: how do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the comparative risk assessment of household air pollution. Annu. Rev. Public Health 35, 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182356 (2014).

Perera, F. Pollution from fossil-fuel combustion is the leading environmental threat to global pediatric health and equity: solutions exist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010016 (2017).

Okello, G., Devereux, G. & Semple, S. Women and girls in resource poor countries experience much greater exposure to household air pollutants than men: results from Uganda and Ethiopia. Environ. Int. 119, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.002 (2018).

Bateson, T. F. & Schwartz, J. Children’s response to air pollutants. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 71, 238–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390701598234 (2008).

Amegah, A. K., Quansah, R. & Jaakkola, J. J. Household air pollution from solid fuel use and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. PLoS ONE 9, e113920. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113920 (2014).

Woolley, K. E. et al. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce household air pollution from solid biomass fuels and improve maternal and child health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indoor Air 32, e12958. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12958 (2022).

World Health Organisation (WHO). Ambient (outdoor) Air Quality and Health (2018).

Fatmi, Z. & Coggon, D. Coronary heart disease and household air pollution from use of solid fuel: a systematic review. Br. Med. Bull. 118, 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldw015 (2016).

Mocumbi, A. O., Stewart, S., Patel, S. & Al-Delaimy, W. K. Cardiovascular effects of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: relevance to Sub-saharan Africa. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 6, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-00234-8 (2019).

Pathak, U. et al. Impact of biomass fuel exposure from traditional stoves on lung functions in adult women of a rural Indian village. Lung India 36, 376–383. https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_477_18 (2019).

Quansah, R. et al. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce household air pollution and/or improve health in homes using solid fuel in low-and-middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 103, 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.03.010 (2017).

Boamah-Kaali, E. et al. Prenatal and postnatal household air pollution exposure and infant growth trajectories: evidence from a rural Ghanaian pregnancy cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 129, 117009. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp8109 (2021).

Gurley, E. S. et al. Indoor exposure to particulate matter and the incidence of acute lower respiratory infections among children: a birth cohort study in urban Bangladesh. Indoor Air 23, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12038 (2013).

Ulziikhuu, B. et al. Portable HEPA filter air cleaner use during pregnancy and children’s cognitive performance at four years of age: the UGAAR randomized controlled trial. Environ. Health Perspect. 130, 67006. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp10302 (2022).

Hutton, G., Rehfuess, E. A. & Tediosi, F. Evaluation of the costs and benefits of interventions to reduce indoor air pollution. Energy Sustain. Dev. 11, 34–43 (2007).

Sovacool, B. K. & Drupady, I. M. Summoning earth and fire: the energy development implications of Grameen Shakti (GS) in Bangladesh. Energy 36, 4445–4459 (2011).

Martin, W. J. 2 et al. Household air pollution in low- and middle-income countries: health risks and research priorities. PLoS Med. 10, e1001455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001455 (2013).

Muller, C. & Yan, H. Household fuel use in developing countries: review of theory and evidence. Energy Econ. J. 70, 429–439 (2016).

Ochieng, C. A., Tonne, C. & Vardoulakis, S. A comparison of fuel use between a low cost, improved wood stove and traditional three-stone stove in rural Kenya. Biomass Bioenergy 58, 258–266 (2013).

von Schirnding, Y. Health and sustainable development: can we rise to the challenge? Lancet 360, 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09777-5 (2002).

World Health Organization (WHO). Air pollution in Mongolia. Bull. World Health Organ. 97, 1 (2019).

Badarch, J. et al. Winter air pollution from domestic coal fired heating in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, is strongly associated with a major seasonal cyclic decrease in successful fecundity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052750 (2021).

Ganbat, G., Soyol-Erdene, T. O. & Jadamba, B. Recent improvement in particulate matter (PM) pollution in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 2280–2288. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2020.04.0170 (2020).

Melekhova, K. A., Lichman, Y. Y., Erkin, Z., Raimbergenov, A. I. & Itemgenova, B. U. Yurt and its role in the culture of the people of Central Asia. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 14, 193–202 (2018).

Balakrishnan, K. et al. Daily average exposures to respirable particulate matter from combustion of biomass fuels in rural households of southern India. Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 1069–1075. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.021101069 (2002).

Bartington, S. E. et al. Patterns of domestic exposure to carbon monoxide and particulate matter in households using biomass fuel in Janakpur, Nepal. Environ. Pollut. 220, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.074 (2017).

World Health Organization (WHO). Air Pollution and Child Health: Prescribing Clean Air (2018).

Al-Janabi, Z., Woolley, K. E., Thomas, G. N. & Bartington, S. E. A cross-sectional analysis of the association between domestic cooking energy source type and respiratory infections among children aged under five years: evidence from demographic and household surveys in 37 low-middle income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168516 (2021).

Dherani, M. et al. Indoor air pollution from unprocessed solid fuel use and pneumonia risk in children aged under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 86, 390–398. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.044529 (2008).

Caleyachetty, R. et al. Exposure to household air pollution from solid cookfuels and childhood stunting: a population-based, cross-sectional study of half a million children in low- and middle-income countries. Int. Health 14, 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihab090 (2022).

Ranathunga, N. et al. Effects of indoor air pollution due to solid fuel combustion on physical growth of children under 5 in Sri Lanka: a descriptive cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 16, e0252230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252230 (2021).

Munroe, R. L. & Gauvain, M. Exposure to open-fire cooking and cognitive performance in children. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 22, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2011.628642 (2012).

Dix-Cooper, L., Eskenazi, B., Romero, C., Balmes, J. & Smith, K. R. Neurodevelopmental performance among school age children in rural Guatemala is associated with prenatal and postnatal exposure to carbon monoxide, a marker for exposure to woodsmoke. Neurotoxicology 33, 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2011.09.004 (2012).

Lin, C. C. et al. Multilevel analysis of air pollution and early childhood neurobehavioral development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 6827–6841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110706827 (2014).

Dashnyam, U. et al. Personal exposure to fine-particle black carbon air pollution among schoolchildren living in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. CAJMS 2, 107 (2016).

Lu, C. et al. Preconceptional, prenatal, and postnatal exposure to home environmental factors and childhood otitis media. Build. Environ. 228, 109886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109886 (2023).

Lu, C. et al. Association between early life exposure to indoor environmental factors and childhood asthma. Build. Environ. 226, 109740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109740 (2022).

Lu, C. et al. Effects of early life exposure to home environmental factors on childhood allergic rhinitis: modifications by outdoor air pollution and temperature. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 244, 114076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114076 (2022).

Lu, C., Wang, L., Jiang, Y., Lan, M. & Wang, F. Preconceptional, pregnant, and postnatal exposure to outdoor air pollution and indoor environmental factors: effects on childhood parasitic infections. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169234 (2024).

Davy, P. K. et al. Air particulate matter pollution in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: determination of composition, source contributions and source locations. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.5094/APR.2011.017 (2011).

Dickinson-Craig, E. et al. Impact assessment of a raw coal ban on maternal and child health outcomes in Ulaanbaatar: a protocol for an interrupted time series study. BMJ Open 13, e061723. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061723 (2023).

Dickinson-Craig, E. et al. Carbon monoxide levels in households using coal-briquette fuelled stoves exceed WHO air quality guidelines in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2022.2123906 (2022).

Balmes, J. R. Household air pollution from domestic combustion of solid fuels and health. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 1979–1987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.04.016 (2019).

Banerjee, B., Protale, E., Adari-Rohani, H. & Bonjour, S. Tracking Access to Nonsolid Fuel for Cooking (2014).

McCracken, J. et al. Intervention to lower household wood smoke exposure in Guatemala reduces ST-segment depression on electrocardiograms. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 1562–1568. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002834 (2011).

Rosbach, J. et al. Classroom ventilation and indoor air quality-results from the FRESH intervention study. Indoor Air 26, 538–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12231 (2016).

Dong, T. T. T., Stock, W. D., Callan, A. C., Strandberg, B. & Hinwood, A. L. Emission factors and composition of PM2.5 from laboratory combustion of five western Australian vegetation types. Sci. Total Environ. 703, 134796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134796 (2020).

Amegah, A. K. & Jaakkola, J. J. Household air pollution and the sustainable development goals. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.15.155812 (2016).

Smith, K. R. et al. Energy and human health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 159–188. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114404 (2013).

Barnes, B. R. Behavioural change, indoor air pollution and child respiratory health in developing countries: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 4607–4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110504607 (2014).

Cordoba, G., Schwartz, L., Woloshin, S., Bae, H. & Gøtzsche, P. C. Definition, reporting, and interpretation of composite outcomes in clinical trials: systematic review. BMJ 341, c3920. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3920 (2010).

Manaseki-Holland, S. Investigation of the Effect of Swaddling on Lower Respiratory Tract Infection in Infants from Mongolia (2005).

Manaseki-Holland, S. et al. Effects of traditional swaddling on development: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 126, e1485–e1492. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1531 (2010).

Narangerel, G., Pollock, J., Manaseki-Holland, S. & Henderson, J. The effects of swaddling on oxygen saturation and respiratory rate of healthy infants in Mongolia. Acta Paediatr. 96, 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00123.x (2007).

Adesina, J. A. et al. Contrasting indoor and ambient particulate matter concentrations and thermal comfort in coal and non-coal burning households at South Africa Highveld. Sci. Total Environ. 699, 134403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134403 (2020).

Warburton, D. et al. Impact of seasonal winter air pollution on health across the lifespan in Mongolia and some putative solutions. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 15, S86–S90. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-758MG (2018).

Yu, K. et al. Association of solid fuel use with risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in rural China. Jama 319, 1351–1361. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2151 (2018).

Distefano, C., Zhu, M. & Mindrila, D. Understanding and using factor scores: considerations for the applied researcher. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 14, 20 (2009).

Schafer, J. L. & Graham, J. W. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 7, 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 (2002).

Roth, P. L. Missing data: a conceptual review for applied psychologists. Pers. Psychol. 47, 537–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01736.x (1994).

Bayley, N. (Psychological Corporation, 1993).

Lanata, C. F. et al. Methodological and quality issues in epidemiological studies of acute lower respiratory infections in children in developing countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 33, 1362–1372. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh229 (2004).

Rudan, I., Tomaskovic, L., Boschi-Pinto, C. & Campbell, H. Global estimate of the incidence of clinical pneumonia among children under five years of age. Bull. World Health Organ. 82, 895–903 (2004).

World Health Organization (WHO). Technical Bases for the WHO Recommendations on the Management of Pneumonia in Children at First-Level Health Facilities (1995).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-Forage: Methods and Development (World Health Organization, 2006).

Microsoft Excel (2018).

Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the families in this study, especially those prepared to give of their time and effort in difficult personal circumstances. We would like to especially thank all of the 270 Mongolian fieldworkers, family and hospital doctors, and data entry staff for successfully collecting and recording the data. We are grateful to the Mongolian collaborators at the Ministry of Health in 2002-6 (in particular Dr. G. Soyolgerel), and staff of Public Health Institute, who supported this project; Mr. Arnold Rillera (from Ministry of Health of Philippines and WHO radiography trainer) for training the radiologists and WHO Geneva Radiology department for facilitating the reading of the CXRs. Finally, without the constant and effective assistance of Prof. G. Choijamts (who at the time was the Director of the Maternal and Child Health Medical Research Centre Hospital), this research would not have been possible. We further thank the Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship staff and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Bloomsbury Centre staff for their support.

Funding

Funding was received from the Wellcome Trust (063468) for the data collection of this study. KEW held a University of Birmingham Global Challenges Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SMH initiated the birth cohort swaddling study, which was conducted in close cooperation with TB, BT and NG. SMH, NT and EDC conceived the idea of conducting the present study on HAP composite scores. ZD conducted the initial analysis and formulated the early drafts under supervision of SMH, NT and EDC. KEW assisted in subsequent data analysis and writing in cooperation with EDC. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Z., Woolley, K.E., Dickinson-Craig, E. et al. Assessing the association between household air pollution exposure and child heath in Mongolia: a birth-cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 3878 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79927-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79927-6