Abstract

Heterocyclic compounds play a crucial role in the drug discovery process and development due to their significant presence and importance. Here, we report a comprehensive analysis of new pyrazolone derivatives, prepared according to a clear-cut, uncomplicated procedure. The pyrazolone derivatives were thoroughly characterized using various methods, such as elemental analysis, NMR, and FT-IR. The molecular docking interactions between the new pyrazolone derivatives and YAP/TEAD target protein observed that compound 4 had the top-ranked binding energy towards YAP/TEAD with a value equal to − 9.670 kcal/mol and this theoretically proves its inhibitory efficacy against YAP/TEAD Hippo signaling pathway. Besides, compound 4 showed the best IC50 against HCT-116, HepG-2, and MCF-7 (in-vitro) with IC50 7.67 ± 0.5, 5.85 ± 0.4, and 6.97 ± 0.5 μM, respectively which confirmed our results towards suppressing YAP/TEAD protein (in-silico) compared with the IC50 of Sorafenib (SOR) reference chemotherapeutic drug 5.47 ± 0.3, 9.18 ± 0.6 and 7.26 ± 0.3 μM, respectively. Also, compound 4 showed no cytotoxic effects against human lung fibroblast normal cell line (WI-38) and its pharmacokinetics were elucidated theoretically using ADMET compared with SOR which observed highly toxic effects on normal cells with IC50 equal to 20.27 ± 0.45 μM. Additionally, compound 4 clarified a powerful antioxidant scavenging activity against DPPH free radicals (in-vitro). Conclusively, newly synthesized pyrazolone derivative 4 could be used as anticancer candidate via inhibiting the YAP/TEAD mediated Hippo signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is the most common disease-related death worldwide. Now, targeted therapy, surgery, and chemotherapy are the main axis for cancer treatment. The effectiveness of cancer therapy has been greatly enhanced by targeted therapy, which has become a common treatment for cancer patients1. The preceding perspective states that the regulation of cell proliferation and death by the Hippo signaling target pathway is essential for controlling organ growth and suppressing tumors2. The Hippo pathway is an attractive therapeutic target because its modulation has a major impact on patient prognosis and chemotherapeutic drug resistance3.

In both Drosophila and mammals, the kinase cascade known as the main Hippo pathway is well-established4. Through binding to 14-3-3 proteins, the Hippo pathway promotes the cytoplasmic retention and degradation of the yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralog TAZ, (the transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif,) via phosphorylating and activating its core kinase cascade, which includes MST1/2 and LATS l/25. When the Hippo pathway is suppressed either physiologically or pathologically, YAP/TAZ is dephosphorylated and then translocated into the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors belonging to the TEA domain family of growth-promoting proteins (TEAD1-4). Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), two downstream genes involved in cell migration and angiogenesis, are transcriptionally and translationally induced by the YAP–TEAD transcriptional complex when they bind to DNA via the TEAD DNA-binding domain6. It was possible to effectively repurpose verteporfin, an FDA-approved medication that is used as a photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy of macular degeneration, as a YAP-TEAD inhibitor7 as it’s unclear how specific it is to YAP-TEAD. Thus, there is a pressing need to identify and create novel YAP-TEAD-mediated Hippo signaling pathway-targeting compounds with high efficacy and minimal side effects.

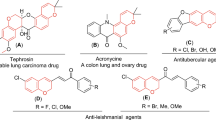

Chalcones are α, β-unsaturated ketones consisting of two aromatic rings, they have a wide range of pharmacological and biological actions, making them intriguing synthons and bioactive scaffolds with significant therapeutic potential. Their substantial biological actions, including antibacterial, antioxidant, antitubercular, anticancer, and antileishmanial properties, are widely acknowledged8,9,10,11. Chalcones are useful in the synthesis of several heterocyclic compounds with potent biological activity, as it makes it easier to synthesize pyrimidinone derivatives by reacting with urea or thiourea12, pyrazoline derivatives by reacting with hydrazine and its derivatives13, pyridine derivatives through the reaction with ethylcyanoacetate14 and pyran derivatives through the reaction with malononitrile and piperidine15,16.

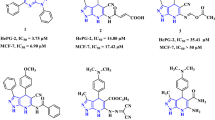

Skeletal pyrazolone derivatives are rich in physiologically significant compounds with a wide range of biological and pharmacological properties, such as antimicrobial, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant.17,18,19,20 The pyrazolone derivatives have a wide range of biological activities due to the strong aromaticity of the ring and the presence of heteroatoms, which directly block the YAP/TEAD Hippo signaling pathway. As illustrated in Fig 1, MSC-410621, and K-97522 are approved drugs that directly inhibited the YAP-TEAD Hippo signaling pathway due to aromaticity and presence of pyrazole moiety, additionally, many anticancer drugs containing pyrazolone, pyrazole, and pyrimidinone core have been reported, such as Metamizole23, Propyphenazone24, Afloqualone25, Betazoleas26, Lonazolac27.

Considering these, we attempted to create a novel class of new pyrazolone derivatives and investigated their antioxidant, and anticancer impact by elucidating their inhibitory role on YAP/TEAD Hippo signaling pathway (in-silico and in-vitro). Additionally, their bioavailability and drug-likeness were examined using ADMET.

Experimental

Materials and instrumentation

The chemicals and instrumental data are all contained in the supplementary file (Section S1).

Synthesis of 3-amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one (1)

Compound 1 was prepared as previously described by Weissberger28.

Synthesis of 4-((4-acetylphenyl)diazenyl)-3-amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-one (2)

To a solution of p-amino acetophenone (13.7 mmol) in concentrated HCl, a solution of sodium nitrite (12.7 mmol) was added slowly. The freshly prepared p-acetyl phenyl diazonium chloride was added to a cooled solution of compound 1 (8.5 mmol) dissolved in pyridine. The reaction mixture was agitated for 2 h, then the product was filtered, and dried.

Orange powder; Yield 74%; mp 91 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.14 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.08–8.11 (m, 9H, Ar–H), 2.59 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone), 2.20 (s, 3H, CH3); IR (KBr) ν: 1600 (CO), 1540 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C17H15N5O2 (321.33): C, 63.54%; H, 4.71%; N, 21.79%. Found: C, 63.34%; H, 4.57%; N, 21.67%.

Synthesis of 5-amino-4-((Z)-(4-((E)-3-(4-(dimethylamino) phenyl) acryloyl) phenyl) diazenyl)-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazole-3-one (3)

A mixture of ethanolic solution of compound 2 (10.0 mmol), 4-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde (10.0 mmol), and sodium hydroxide (20.0 mmol) was agitated for 10 h at room temperature, then put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Dark brown powder; Yield 81%; mp 114 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.09–8.35 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 7.55 (d, J=11.55 Hz, 1H,=CH-Ar), 6.74 (d, J=12.00 Hz, 1H, COCH=), 3.04 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.84 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm):154.73 (C=O chalcone), 152.51 (C=O pyrazolone), 145.51 (C = N pyrazolone), 111.52–137.28 (Ar–C), 122.98, 138.22 (C-Olefinic), 79.78 (CH pyrazolone), 55.34 (N(CH3)2); IR (KBr) ν: 3400 (NH2), 1660 (C=O), 1520 (C=N),1500 (N=N); MS m/z (%): 452.35 [M+];Anal. Calcd for C26H24N6O2 (452.20): C,69.01%; H,5.35%; N,18.57%. Found: C,68.91%; H,5.55%; N,18.39%.

Synthesis of 3-amino-4-((4-(5-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-3-yl)phenyl) diazenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-one (4)

A mixture of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and phenylhydrazine (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in acetic acid for 9 h. the mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Green powder; Yield 73%; mp 96 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.57 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.68–9.72 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 3.74 (t, J = 10.52 Hz, 1H, CH-CH2), 2.91 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.67 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone), 2.03(d, J = 12.23 Hz, 2H, CH2) ; IR (KBr) ν: 1670 (C=O), 1650 (C=N), 1510 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C32H30N8O (542.25):C,70.83%; H,5.57%; N,20.65%. Found: C,70.75%; H,5.49%; N,20.59%.

4-((4-(1-acetyl-5-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-3-yl)phenyl) diazenyl)-3-amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-one (5)

A mixture of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and hydrazine hydrate (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in ethanol for 7 h. the mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Dark brown powder; Yield 87%; mp 133 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 8.49 (s,1H, NH ), 6.69–8.03 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 4.72 (t, J = 11.18 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.99 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone), 2.86 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.02 (d, J = 11.95 Hz, 2H,CH2); IR (KBr) ν: 3150 (NH), 1610 (C = O), 1580 (C = N), 1540 (N = N); MS m/z (%): 466.20 [M+]; Anal. Calcd for C26H26N8O (466.22):C,66.94%; H,5.62%; N,24.02%. Found: C,66.86%; H,5.56%; N,23.94%.

4-((4-(1-acetyl-5-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-3-yl)phenyl) diazenyl)-3-amino-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-one (6)

A mixture of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and hydrazine hydrate (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in acetic acid for 8 h. The mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Brown powder; Yield 75%; mp 74 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.65–8.39 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 4.67 (t, J = 12.04 Hz, 1H, CH), 2.99 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone), 2.84 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.27 (d, J = 11.75 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.91 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm):171.68 (C=O pyrazolone), 166.97 (C=O pyrazole), 159.68 (C=O acetyl), 151.74 (C=N pyrazole), 149.79 (C=N pyrazolone), 111.05–130.42 (Ar–C), 75.22 (CH pyrazolone), 35.81 (N(CH3)2), 21.24 (CH3) ; IR (KBr) ν: 1650 (C=O), 1540 (C=N), 1500 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C28H28N8O2 (508.23):C,66.13%; H,5.55%; N,22.03%. Found: C,66.11%; H,5.47%; N,21.97%.

Synthesis of 3-amino-4-((4-(6-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-4-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-one (7)

An ethanolic solution of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and urea (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in HCl for 7 h. the mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Dark brown powder; Yield 74%; mp 145 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 9.15 (s,1H, NH pyrimidinone), 6.97–8.19 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 5.72 (s, 1H, CH-pyrimidinone), 3.01 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.84 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm):162.37 (C=O pyrazolone), 160.73 (C=N pyrimidinone), 158.53 (C-NH), 155.37 (C=O pyrimidinone), 151.59 (C=N pyrazolone), 111.54–130.00 (Ar–C), 79.80 (CH pyrazolone), 45.54 (N(CH3)2); IR (KBr) ν: 3400 (NH), 1615 (C=O), 1530 (C=N), 1500 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C27H24N8O2(492.20): C,65.84%; H,4.91%; N,22.75%. Found: C,65.68%; H,4.77%; N,22.67%.

Synthesis of 3-amino-4-((4-(6-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-2-thioxo-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-4-yl) phenyl) diazenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one (8)

An ethanolic solution of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and thiourea (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in NaOH for 8 h. The mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Redish brown powder; Yield 73%; mp 103 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 9.19 (s,1H, NH pyrimidinthione), 6.75–8.19 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 5.90 (s, 1H, CH-pyrimidinone), 3.13 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.61 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); IR (KBr) ν: 3420 (NH), 1618 (C=O), 1540 (C=N), 1513 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C27H24N8OS (508.18):C,63.76%; H,4.76%; N,22.03%; S,6.30%. Found: C,63.68%; H,4.66%; N,22.01%; S,6.22%.

Synthesis of (E)-2-amino-6-(4-((3-amino-5-oxo-1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-4-yl) diazenyl)phenyl)-4-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-4H-pyran-3-carbonitrile (9)

An ethanolic solution of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), and malononitrile (10.0 mmol) was refluxed in HCl for 8 h. The mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Orange powder; Yield 79%; mp 139 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.65 (s, 2H, NH2), 9.37 (s, 2H, NH2-pyran), 6.59–8.28 (m, 13H, Ar–H), 5.81 (d, J = 9.65 Hz, 1H,=CH Pyran), 5.33(d, J = 11.75 Hz, 1H, CH Pyran), 2.98 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.68 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm):161.10 (C=O pyrazolone), 158.53 (C-NH2 pyran), 151.59 (C=N pyrazolone), 123.34 (CN), 111.90–130.27 (Ar–C), 75.08 (CH pyrazolone), 44.61 (C–CN), 23.29 (N(CH3)2), 22.64 (CH-pyran); IR (KBr) ν: 3430 (NH2), 1610 (C=O), 1550 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C29H26N8O2 (518.22):C,67.17%; H,5.05%; N,21.61%. Found: C,67.05%; H,4.95%; N,21.55%.

Synthesis of (E)-2-amino-6-(4-((3-amino-5-oxo-1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazole-4-yl)diazenyl)phenyl)-4-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)nicotinonitrile (10)

An ethanolic solution of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), malononitrile (10.0 mmol), and ammonium acetate (20.0 mmol) was refluxed for 10 h. The mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Brown powder; Yield 82%; mp 116 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.45 (s, 2H, NH2), 9.15 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.71–8.04 (m, 14H, Ar–H), 3.10 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.99 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); IR (KBr) ν: 3415 (NH2), 1660 (C=O), 1520 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C29H25N9O (515.22):C,67.56%; H,4.89%; N,24.45%. Found: C,67.48%; H,4.81%; N,24.39%.

(E)-6-(4-((3-amino-5-oxo-1-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)diazenyl) phenyl)-4-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3-carbonitrile (11)

An ethanolic solution of compound 3 (10.0 mmol), ethyl cyanoacetate (10.0 mmol), and ammonium acetate (20.0 mmol) was refluxed for 9 h. the mixture was put into freezing water, filtered, and dried.

Reddish brown powder; Yield 69%; mp 92 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.78 (s, 2H, NH2), 9.27 (s,1H, NH), 6.73–8.18 (m, 14H, Ar–H), 3.00 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 2.71 (s, 1H, CH-pyrazolone); IR (KBr) ν: 3390 (NH), 1620 (C=O), 1530 (N=N); Anal. Calcd for C29H24N8O2 (516.20):C,67.43%; H,4.68%; N,21.69%. Found: C,67.35%; H,4.62%; N,21.61%.

Biological investigations

Antioxidant activity using DPPH

The synthesized pyrazolone derivatives’ capacity to scavenge free radicals DPPH was assessed using a modified Zheleva-Dimitrova technique29. Also, the DPPH radical was investigated to L-ascorbic acid with concentrations (10–100 μM) that serving as the standard positive control and the scavenging percent was calculated by Eq. 1.

Docking and ADMET in-silico studies

The pyrazolone derivatives’ binding mechanisms to the target protein YAP/TEAD were assessed using molecular docking study. The RCSB protein data (PDB: #3KYS) (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3KYS) gave the crystal structures of the target30. The efficiency of the target protein was increased by removing heteroatoms and water molecules. Additionally, the 2D structures of the generated analogs were created in the cdx format and subsequently transformed into motif files (3D structures) through the utilization of ChemDraw Ultra 8.0 (https://en.freedownloadmanager.org/users-choice/Chemdraw_Ultra_8.0.html). Molegro Virtual Docker (2008) (http://molexus.io/molegro-virtual-docker/) was used to study the enzyme-ligand interaction31. The intermolecular interactions between the YAP/TEAD protein and synthetic pyrazolone derivatives were observed using the Discovery Studio 3.5 software (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download). The online tool SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) was utilized to estimate ADMET features.

Anticancer assessments (in-vitro)

Cell lines

Mammary gland (MCF-7;# ATCC HTB-22), colorectal adenocarcinoma (HCT-116; # ATCC CCL-247)), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG-2; #ATCC HB-8065), and human lung fibroblast (WI-38; # ATCC CCL-75). The ATCC cell line was obtained via the Holding Company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA), Cairo, Egypt.

MTT assay

The MTT test was utilized to ascertain the pyrazolone derivatives’ inhibitory effects on cell growth using the aforementioned cell lines. This colorimetric assay is based on the transformation of yellow tetrazolium bromide (MTT) by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in living cells into a purple formazan derivative. The RPMI-1640 medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum to cultivate cell lines. At 37° C in an incubator with 5% CO2, 100 units/mL of penicillin and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin were introduced as antibiotics. The cell lines were seeded by 1.0 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate and kept at 37 °C for 24 h with 5% CO2. Following incubation, the cells were subjected to several concentrations of newly synthesized pyrazolone derivatives and left for 48 h incubation.20 µL of a 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added and incubated for 4 h after the drug treatment. To dissolve the purple formazan produced in each well, 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied. The colorimetric test is performed at 630 nm absorbance and recorded using a plate reader (EXL 800, USA)32.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 (San Diego, CA) (GraphPad Prism 6, https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/) was used to calculate the IC50 values and the data was expressed as mean ± SE.

Results and discussion

Chemistry of the novel compounds

Initially, compound 1 was prepared through the reaction of ethyl cyanoacetate and phenyl hydrazine as described previously by Weissberger28 as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The coupling of p-acetyl phenyl diazonium chloride with compound 1 led to the formation of azo pyrazolone 2 with 74% yield (Fig. 3). The structure of compound 2 was confirmed with elemental analyses and different spectral data. The IR analysis showed absorption bands at 1600 cm−1 for the C=O group and 1540 cm−1 for the N=N group. The 1H NMR spectrum revealed a new singlet signal resonated at δ 2.20 ppm attributed to CH3 of the acetyl group.

Further modification of compound 2 with 4-(dimethylamino) benzaldehyde in a basic medium led to the formation of pyrazolone chalcone 3 with 81% yield (Fig. 3). The IR analysis showed absorption bands at 1660 cm−1 for C=O group, 1520 cm−1 for C=N group, and 1500 cm−1 for N=N group. The 1H NMR spectrum revealed three new signals resonated at δ 7.55, 6.74, and 3.04 ppm attributed to two olefinic protons, and N(CH3)2 respectively.

The reaction of compound 3 with phenylhydrazine in an acidic medium led to the formation of compound 4 with 73% yield (Fig. 4). The IR showed different bands at 1670, 1650, and 1510 cm−1 which belonged to C=O, C=N, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum revealed the presence of a new triplet signal at δ 3.74 ppm due to CH-pyrazole, and a doublet signal at δ 2.03 ppm assigned to CH2-pyrazole.

Additionally, the reaction of the ethanolic solution of compound 3 with hydrazine hydrate led to the formation of compound 5 with 87% yield. The reaction of compound 3 with hydrazine hydrate in acetic acid glacial led to the formation of compound 6 with 74% yield. (Fig. 4). The IR of compound 5 showed absorption bands at 3150, 1610, 1580, and 1540 cm−1 which belonged to NH, C=O, C=N, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed a new singlet signal at δ 8.49 ppm due to NH-pyrazole, a triplet signal at δ 4.72 ppm due to CH-pyrazole, and a doublet signal at δ 2.02 ppm assigned to CH2-pyrazole. The IR of compound 6 showed different bands at 1650, 1540, and 1500 cm−1 which belonged to C=O, C=N, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed a new triplet signal at δ 4.76 ppm due to CH-pyrazole, a doublet signal at δ 2.27 ppm assigned to CH2-pyrazole, and a singlet signal at δ 1.91 ppm due to CH3 of acetyl group. The suggested mechanism for the synthesis of compounds 4–6 was illustrated in Figs. 5, 6.

As shown in Fig. 7, the reaction of compound 3 with urea in an acidic medium and thiourea in a basic medium led to the formation of compounds 7, and 8. The IR spectrum of these compounds showed absorption bands at 3400–3420, 1610–1615, 1530–1540, and 1500–1513 cm−1 which belonged to NH, C=O, C=N, and N=N respectively. The 1H NMR spectrum revealed the presence of a new singlet signal at δ 9.15–9.19 characteristic of NH proton, and a singlet signal at δ 5.72–5.90 ppm due to CH-pyrimidinone. The suggested mechanism for the synthesis of compounds 7, and 8 is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Analogously, the reaction of compound 3 with malononitrile in pyridine led to the formation of compound 9 with a 79% yield. While the reaction with malononitrile in ammonium acetate led to the formation of compound 10 with 82% yield. (Fig. 9). The IR of compound 9 showed different bands at 3430, 1610, and 1550 cm−1 which belonged to NH2, C=O, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed a new singlet signal at δ 9.37 ppm due to NH2 protons, a doublet signal at δ 5.81 ppm due to=CH-pyran, and a doublet signal at δ 5.33 ppm due to CH-pyran. The IR of compound 10 showed absorption bands at 3415, 1600, and 1520 cm−1 which belonged to NH2, C=O, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed a new singlet signal at δ 8.49 ppm due to NH2 protons.

Finally, the reaction of compound 3 with ethyl cyanoacetate afforded compound 11 with 69% yield. The IR spectra showed different bands at 3390, 1620, and 1530 cm−1 which belonged to NH, C=O, and N=N respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum showed a new singlet signal at δ 9.27 ppm due to the NH proton. The suggested mechanism for the synthesis of compounds 9–11 was illustrated in Figs. 10, 11, and 12

Antioxidant capacity

Using the stable DPPH radical, the antioxidant capacity of these newly synthesized pyrazolones was assessed by monitoring the change in absorbance generated, as illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14. It was elucidated that the antioxidant activity rose along with the concentration of pyrazolone derivatives. Compound 4 showed a higher DPPH scavenging activity with IC50 value (19.88 ± 0.15 μM) compared to the standard L-ascorbic acid (IC50 = 16.81 ± 0.10 µM). Furthermore, our results observed that compounds 5, 6, and 9 showed a moderate scavenging impact, with activities equal to 29.28 ± 0.16, 32.40 ± 0.20 and 47.07 ± 0.24 µM respectively. Whereas compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11 demonstrated a weak capacity to quench free radicals with IC50 93.7 ± 0.47, 65.54 ± 0.32, 74.30 ± 0.38 and 53.67 ± 0.29 µM respectively compared to the standard L-ascorbic acid.

Docking studies

Molecular docking is a powerful tool for quickly and accurately estimating protein–ligand complex binding energies and biomolecular conformations, it has been widely used to identify novel drugs. The new pyrazolone derivative ligands (4–11) in this instance were docked into YAP/TEAD as a well-known and enticing therapeutic target protein-protein complex in the Hippo signaling pathway for the creation of anticancer medications. The Hippo pathway has been the subject of numerous studies in the domains of oncology and regenerative medicine, which have also indicated its possible significance as inhibitory targets for drug development or as regulatory factors in human biology. The Hippo pathway is generally composed of two constitutive modules: the downstream transcriptional modules, which primarily involve the YAP/TEAD complex, and the upstream serine/threonine kinase cascade, which includes MST1/2 and LATS1/233.

Oncogenes as Yes-associated protein (YAP) was closely homolog with the PDZ-binding motif (TAZ). YAP and TAZ function as transcription co-activators, forming a binding complex with DNA to trigger target gene transcription and consequent transformation activity. The transcriptional enhancer factor (TEA)-domain (TEAD) family is primarily responsible for mediating key transforming activities of YAP and TAZ, such as those related to cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. In YAP-dependent cancer models, the YAP/TEAD genetic and pharmacological interactions dramatically reduced tumorigenesis34. Thus, the YAP/TEAD complex has emerged as an attractive target for the development of anti-cancer drugs35. All novel pyrazolone’s interactions with target YAP/TEAD protein were described in Table 1; Fig. 15. Our results elucidated that compound 4 exhibited the most binding energy against target YAP/TEAD protein with a value equal to − 9.670 kcal/mol. Furthermore, compounds 5, 6, and 9 elucidated moderate inhibitory effect with binding energies equal to -8.081 and − 7.814 and − 7.113 kcal/mol respectively. On the other hand, compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11 observed slightly weak binding energy equal to − 6.530, − 4.605, − 5.203, and − 7.005 kcal/mol respectively. Therefore, compound 4 was strongly recommended to be used as an anticancer agent via its prospective inhibitory effect on the YAP/TEAD-mediated Hippo signaling pathway.

ADMET features

Figure 16 ascertains the bioavailability and drug likeness properties of the examined pyrazolone derivatives (4–11). The total polar surface area (TPSA) of the pyrazolone derivatives (4–11) ranged from 102.25 to 149.35 Å2, which means that they had adequate oral bioavailability and satisfied all the criteria for outstanding permeability. They also showed how to demonstrate flexibility by showing rotatable bonds between 0 and 10. Their enhanced solubility in cellular membranes was facilitated by their hydrogen bound accepted (HBA) and hydrogen bound donated (HBD) values being in the fulfilled range. Table 2 illustrates that octanol/water partition coefficient (log p) values less than 5 were indicative of good lipophilicity features. Furthermore, the pyrazolone derivatives had higher human intestinal absorption (% HIA) ratings in accordance with the ADMET criteria, indicating that the human intestinal could absorb them more effectively. The tested pyrazolone derivatives have a great safety profile for the central nervous system (CNS) because they do not cross the blood–brain barrier. Last but not least, every AMES toxicity and carcinogenicity test result was negative, demonstrating their biosafety.

Anticancer in-vitro study

In research on new anticancer agents, the most common experimental screening method after the theoretical study was testing against a group of different cancer cell lines. In this study, an MTT assay was done to determine the antitumor effect of pyrazolone derivatives (4–11) compounds on HCT-116, HepG2, and MCF-7 proliferation, and the cytotoxicity limit on WI-38 normal cell line after 48 h, Figs. 17 and 18. Compound 4 showed significant antitumor effects on HCT-116, HepG2, and MCF-7 cancer cell lines with an IC50 equal to 7.67 ± 0.5, 5.85 ± 0.4, and 6.97 ± 0.5 μM, respectively. Also, compounds 5 and 6 showed remarkable antitumor effects on HCT-116, HepG2, and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values (8.14 ± 0.6, 13.98 ± 1.1, 10.34 ± 0.9 μM) (16.53 ± 1.3, 25.62 ± 1.7, 19.81 ± 1.5 μM) respectively. On the other hand, compounds 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 showed moderate to weak impact on all panels of cancer cell lines compared with the IC50 of Sorafenib (SOR) reference chemotherapeutic drug 5.47 ± 0.3, 9.18 ± 0.6 and 7.26 ± 0.3 μM, respectively. Moreover, all new pyrazolone derivatives (4–11) showed lower cytotoxic effects on WI-38 normal cells compared with SOR which observed highly toxic effects on normal cells with IC50 equal to 20.27 ± 0.45 μM. This signifies that compound 4, was effective against proliferative cancer through inhibiting YAP/TEAD mediated Hippo signaling pathway which represented a promising cascade that controls both proliferation and apoptosis. This pathway is crucially regulated by YAP, which does this by shifting its location within the cytoplasm or nucleus. Since YAP lacks a DNA binding domain, its ability to regulate target genes is dependent on its interaction with TEAD36. As a result of the newly synthesized pyrazolone derivatives’ potential inhibition of YAP/TEAD target protein, compound 4 could be exploited as promise therapeutic candidate for cancer therapy amoung all synthesized pyrazolones, which by the way confirmed the docking in-silico studies.

Our compounds exhibit antioxidant and YAP/TEAD inhibition simultaneously. The suppression of YAP/TEAD targets cancer cells, whereas the antioxidant actions may assist protecting normal cells. Our cell viability investigations have shown anticancer effects, which may be attributed to this dual action. Our compounds’ combination of these qualities’ points to a multi-targeted strategy for treating cancer.

Structure-anti-cancer activity relationship (SAR)

Several studies have investigated the structure activity relationship (SAR relationship) of pyrazolones and showed that they have good anti-cancer properties. As illustrated in Fig. 19. The pyrazolone derivatives have a wide range of biological activities due to the presence of different types of interactions with the target YAP/TEAD protein. Firstly, the π-π interaction with the target protein was due to the strong aromaticity of the ring and the presence of heteroatoms like pyrazolone and pyrazole.37 secondly, the Hydrogen bonding with the target protein was found due to the presence of both amino group (H. Bond donor) and carbonyl group (H. Bond acceptor).38 Finally, some electrostatic attraction forces with the target protein were found due to the presence of azo linker.39

Conclusion

New pyrazolone derivatives (4–11) were successfully synthesized and characterized via different spectroscopic techniques. Several important conclusions were obtained from our extensive research.

-

1.

Antioxidant activity; Derivative 4 clarified the most potent antioxidant activity among all other derivatives.

-

2.

Molecular Docking; This in-silico study revealed that compound 4, could be a targeted anticancer agent because it has a good docking score due to hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions with crucial residues within the binding pocket of the YAP/TEAD target protein.

-

3.

In-vitro cytotoxic studies; Confirming the docking inhibitory results, the in-vitro anti-cancer activities, against a panel of cancer cell lines were interpreted as the suppressive impact of compound 4 where it triggered apoptosis and obstructed cell survival, growth, via inhibiting of YAP/TEAD mediated Hippo signaling pathway.

Overall, our data identify compound 4 as a new promising candidate for targeted anticancer therapy. Because of its dual role as a potent antioxidant and YAP/TEAD inhibitor, more research is needed to fully investigate its therapeutic potential against various cancer types.

Data availability

The cell lines were provided from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) via VACSERA, Cairo, Egypt, and all accession codes were added Mammary gland (MCF-7;# ATCC HTB-22), colorectal adenocarcinoma (HCT-116; # ATCC CCL-247), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG-2; #ATCC HB-8065), and human lung fibroblast (WI-38; # ATCC CCL-75). The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in Macromolecule protein structure, and can be deposited in the worldwide protein data bank repository, (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3KYS)

References

Cao, W., Chen, H. D., Yu, Y. W., Li, N. & Chen, W. Q. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics. Chin. Med. J. Engl. 134, 783–791 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev. Cell. 14, 377–387 (2008).

ZhaoY, Y. X. The Hippo pathway in chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Int. J. Cancer. 137, 2767–2773 (2015).

Yu, F. X. & Guan, K. L. The Hippo pathway: Regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 27, 355–371 (2013).

Yu, F. X. et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 150, 780–791 (2012).

Lai, D., Ho, K. C. & HaoY, Y. X. Taxol resistance in breast cancer cells is mediated by the hippo pathway component TAZ and its downstream transcriptional targets Cyr61 and CTGF. Cancer Res. 71, 2728–2738 (2011).

Son, Y., Jaeyeal, K., Yongchan, K., SungG, T. K. & Jinha, Y. Discovery of dioxo-benzo [b] thiophene derivatives as potent YAP-TEAD interaction inhibitors for treating breast cancer. Bioorganic Chem. 131, 106274 (2023).

Şenol, H., Mansour, G., Gülbahar, Ö., Alim, T. & Uğur, G. Novel chalcone derivatives of ursolic acid as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, biological activity, ADME prediction, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1295, 136804 (2024).

Noser, A. A., El-Barbary, A. A., Maha, M. S., Hayam, A. & Mohamed, Sh. Synthesis and molecular docking simulations of novel azepines based on quinazolinone moiety as prospective antimicrobial and antitumor hedgehog signaling inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 14, 3530 (2024).

Setshedi, K. J. et al. Synthesis and in vitro biological activity of chalcone derivatives as potential antiparasitic agents. Med. Chem. Res. 33, 977–988 (2024).

Noser, A. A., Saham, A. I., Hayam, A., Nora, M. A. & Hamada, S. A. Pyrazole-vaniline Schiff base disperse azo dyes for UV protective clothing: synthesis, characterization, comparative study of UPF, dyeing properties and potent antimicrobial activity. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 20, 2963–2976 (2023).

Salem, M. M., Marian, N. G. & Ahmed, A. N. Synthesis, molecular docking, and in-vitro studies of pyrimidine-2-thione derivatives as antineoplastic agents via potential RAS/PI3K/Akt/JNK inhibition in breast carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep. 12, 22146 (2022).

Tiwari, A., Anjaneyulu, B. & Anirudh, S. B. An overview on synthesis and biological activity of chalcone derived pyrazolines. ChemistrySelect. 6, 12757–12795 (2021).

Abdo, M., Nadia, Y., Eman, M. & Rafat, M. Synthesis and evaluation of novel 4 H-pyrazole and thiophene derivatives derived from chalcone as potential anti-proliferative agents, Pim-1 kinase inhibitors, and PAINS. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57, 1993–2009 (2020).

Shafi, S. S. Biological evaluation of some novel chalcones and their derivatives. Indian J. Chem.-Sect. B (IJC-B) 60, 1132–1136 (2021).

Ramadan, S. K. & Sameh, A. R. Synthesis, density functional theory, and cytotoxic activity of some heterocyclic systems derived from 3-(3-(1, 3-diphenyl-1 H-pyrazol-4-yl) acryloyl)-2 H-chromen-2-one. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 19, 187–201 (2022).

Patil, J. V., Soman, S. S., Umar, S., Girase, P. & Balakrishnan, S. Synthesis of pyrazolone derivatives of coumarin as anticancer agents. ChemistrySelect. 9, e202303391 (2024).

Emam, S. M., Samir, B. & Ahmed, A. M. Schiff base coordination compounds including thiosemicarbazide derivative and 4-benzoyl-1, 3-diphenyl-5-pyrazolone: Synthesis, structural spectral characterization and biological activity. Results Chem. 5, 100725 (2023).

Noser, A. A., Abdelmonsef, A. H. & Maha, M. S. Design, synthesis and molecular docking of novel substituted azepines as inhibitors of PI3K/Akt/TSC2/mTOR signaling pathway in colorectal carcinoma. Bioorganic Chem. 131, 106299 (2023).

Noser, A. A., Sh, I. A., Aboubakr, H. A. & Maha, M. S. Newly synthesized pyrazolinone chalcones as anticancer agents via inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/ERK1/2 signaling pathway. ACS Omega. 7, 25265–25277 (2022).

Heinrich, T. et al. "Optimization of TEAD P-site binding fragment hit into in vivo active lead MSC-4106. J. Med. Chem. 13, 9206–9229 (2022).

Kaneda, A. et al. The novel potent TEAD inhibitor, K-975, inhibits YAP1/TAZ-TEAD protein-protein interactions and exerts an anti-tumor effect on malignant pleural mesothelioma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 12, 4399 (2020).

Sebode, M. et al. Metamizole: An underrated agent causing severe idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. British J. Clin. Pharmacol. 86, 1406 (2020).

Patel, Z., Falguni, T., Rati, K. & Prasad, T. Simultaneous estimation of propyphenazone, flurbiprofen, and their mutual prodrug by high-performance liquid chromatography method. Sep. Sci. Plus. 7, 2300104 (2024).

Ochiai, T. & Ryuichi, I. Pharmacological studies on 6-amino-2-fluoromethyl-3-(O-tolyl)-4 (3H)-quinazolinone (afloqualone), a new centrally acting muscle relaxant(II) Effects on the spinal reflex potential and the rigidity. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 32, 427–438 (1982).

WengerJ, F. E. O., Adolphus, J. & Marian, S. Gastric analysis with oral stimuli: A comparative study with maximal betazole stimulation. Am. J. Digest Dis. 16, 151–155 (1971).

Harras, M. F., Rehab, S. & Omkulthom, M. A. Discovery of new non-acidic lonazolac analogues with COX-2 selectivity as potent anti-inflammatory agents. MedChemComm. 10, 1775–1788 (2019).

Weissberger, A., Porter, H. D. & Gregory, W. A. Investigation of pyrazole compounds VII 1 the reaction of some hydrazines with Ethyl malonate monoimidoester. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 66, 1851–1855 (1944).

Hamada, W. M. et al. Simple dihydropyridine-based colorimetric chemosensors for heavy metal ion detection, biological evaluation, molecular docking, and ADMET profiling. Sci. Rep. 13, 15420 (2023).

Son, Y. et al. Discovery of dioxo-benzo [b] thiophene derivatives as potent YAP-TEAD interaction inhibitors for treating breast cancer. Bioorganic Chem. 131, 106274 (2023).

Hekal, H. A., Hammad, O. M., El-Brollosy, N. R., Salem, M. M. & Allayeh, A. K. Design, synthesis, docking, and antiviral evaluation of some novel pyrimidinone-based α-aminophosphonates as potent H1N1 and HCoV-229E inhibitors. Bioorganic Chem. 147, 107353 (2024).

El-Nahass, M. N. et al. Functionalized gold nanorods turn-on chemosensor for selective detection of Cd2+ ions, bio-imaging, and antineoplastic evaluations. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 21, 699–718 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 22, 1962–1971 (2008).

Liu-Chittenden, Y. et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 26, 1300–1305 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. Tumor-selective proteotoxicity of verteporfin inhibits colon cancer progression independently of YAP1. Sci. Signal. 8, 98 (2015).

Vassilev, A., Kaneko, K. J., Shu, H., Zhao, Y. & DePamphilis, M. L. TEAD/TEF transcription factors utilize the activation domain of YAP65, a Src/Yes-associated protein localized in the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 15, 1229–1241 (2001).

Noser, A. A., Mohamed, E., Donia, T. & Aboubakr, H. A. Synthesis in silico and in vitro assessment of new quinazolinones as anticancer agents via potential AKT inhibition. Molecules. 25, 4780 (2020).

Ali, Y., Hamid, S. A. & Rashid, U. Biomedical applications of aromatic azo compounds. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 18, 1548–1558 (2018).

Ki, L. S., Sharan, M., Norhafiza, M. A. & Noor, H. N. A review of the structure activity relationship of natural and synthetic antimetastatic compounds. Biomolecules. 10, 138 (2020).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. A. N., M. M. S., and E. M. E.: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, and Methodology. M. M. S.: Formal analysis. A. I. S., A. A. N., and M. H. B.: Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noser, A.A., Salem, M.M., Baren, M.H. et al. Discovering the inhibition of YAP/TEAD Hippo signaling pathway via new pyrazolone derivatives: synthesis, molecular docking and biological investigations. Sci Rep 14, 28859 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79992-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79992-x