Abstract

Laparoscopic hepatectomy has minimally invasive advantages, but reports on laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy (LRAS) are rare. Herein, we try to explore the benefits and drawbacks of LRAS by comparing it with open right anterior sectionectomy (ORAS). Between January 2015 and September 2023, 39 patients who underwent LRAS (n = 18) or ORAS (n = 21) were enrolled in the study. The patients’ characteristics, intraoperative details, and postoperative outcomes were compared between the two groups. No significant differences in the preoperative data were observed between the two groups. The LRAS group had significantly lesser blood loss (P = 0.019), a shorter hospital stay (P = 0.045), and a higher rate of bile leak (P = 0.039) than the ORAS group. There was no significant difference in the operative time (P = 0.156), transfusion rate (P = 0.385), hospital expenses (P = 0.511), rate of other complications, postoperative white blood cell count, and alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels between the two groups (P > 0.05). Beside, there was no significant difference in disease-free survival (P = 0.351) or overall survival (P = 0.613) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma between the two groups. LRAS is a safe and feasible surgical procedure. It may be preferred for lesions in the right anterior lobe of the liver.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In now day, laparoscopic hepatectomy (LH) has been proven to be a safe and reliable surgical method with minimally invasive advantages1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. However, laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy (LRAS) has been rarely reported due to its special anatomical features. The hepatic pedicle of the right anterior lobe is located deep in the liver parenchyma behind the gallbladder neck, and its exposure requires the separation of a part of the liver parenchyma and hepatic cystic plate. Furthermore, right anterior sectionectomy involves the resection of two liver segments, dissection of substantial parenchyma, and processing of numerous tributaries3. It is necessary to expose the middle hepatic vein (MHV) and right hepatic vein (RHV), which carry a large amount of venous reflux from the liver parenchyma, causing thickening of the main trunk and development of numerous branches. Thus, according to the difficulty coefficient table of laparoscopic liver cancer resection, LRAS has the highest difficulty score among the laparoscopic liver cancer resections12. For right anterior lesions, laparoscopic right hemihepatectomy has been frequently performed instead of LRAS to reduce surgical difficulties. However, it leads to the sacrifice of large volumes of noncancerous hepatic parenchyma and does not maximize the benefits for patients, particularly those with cirrhosis. Therefore, we aimed to explored and summarized the benefits and drawbacks of LRAS and compared them with with those of open right anterior sectionectomy (ORAS).

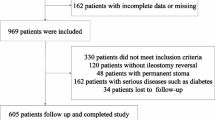

Patients and methods

Patients and grouping

This study was conducted at the Department of General Surgery and approved by the Institutional Review Board committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was performed in accordance with the established national and institutional ethical guidelines regarding the involvement of human participants and the use of human tissues for research8,9. Between January 2015 and September 2023, 39 patients who underwent LRAS (n = 18) or ORAS (n = 21) were enrolled in the study. The post operative blood tests were collected at the first day after surgery. Hospital expense refers to all medical expenses incurred by the patient during hospitalization. The patient data were collected from the hospital database. The patients’ clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

LRAS procedure

The patient’s position and the layout of the Trocars were according to our previous in our previous research8,9. The surgical technique described in a previous study was used (Fig. 1)13. The hepatic portal plate was exposed after the gallbladder was resected. Thereafter, the liver parenchyma was transected under ultrasonographic guidance to expose and block the Glissonean pedicle of the right anterior lobe. The liver parenchyma was transected along the hepatic ischemic line and the right side of the MHV. The separation of the liver parenchyma was continued along the other side hepatic ischemic line and the left side of the RHV. Preoperative 3D reconstruction was performed to evaluate the relationship between the lesion and hepatic vein, and determine the cutting plane (Fig. 2). Laparoscopic ultrasonography was used to determine the intrahepatic vessel anatomy. The intrahepatic vascular or biliary branches were ligated using clips (Hem-o-lok). We employed the Pringle maneuver when the abovementioned method could not be implemented. Finally, the Glissonean pedicle of the right anterior lobe was divided, and the specimen was removed (Supplementary Fig. 1). The steps of ORAS were similar to those of LRAS. Figure 3 shows the radiological imaging of a patient.

Surgical steps of LRAS. (A) Gallbladder removal. (B) The hepatic portal vein was blocked with a strap. (C) The Glissonean pedicle of the right anterior lobe was dissected. (D) The hepatic ischemic line of the right anterior lobe. (E) The middle hepatic vein branches of the V and VIII segments were severed. (F) The parenchyma was transected to identify the terminal portion of the RHV. (G) The hepatic vein branches of the RHV were ligated and severed. (H) The Glissonean pedicle of the right anterior lobe was severed. (I) MHV and RHV were exposed on the liver section after LRAS. LRAS, laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy; RHV, right hepatic vein; MHV, middle hepatic vein.

Statistical analysis

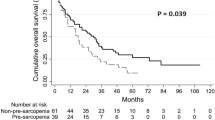

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 17; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations or medians (ranges). The categorical variables were expressed as frequencies. The continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, whereas the categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Patient survival (disease-free survival and overall survival) was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and they were compared using the log-rank test.

Results

Patient characteristics

Thirty-nine patients who underwent LRAS (n = 18) or ORAS (n = 21) were enrolled in the study. The preoperative features, intraoperative details, and postoperative outcomes of the patients are included in Table 1. There were no significant intergroup differences in terms of sex, age, body mass index, lesion diameter, or liver function (P > 0.05).

Perioperative outcomes

The surgical outcomes are shown in Table 1. The patients who underwent LRAS had lesser blood loss (204 ± 80 vs. 286 ± 118 mL, P = 0.019), a shorter hospital stay (8.6 ± 2.4 vs. 10.2 ± 2.6 days, P = 0.045), and a higher rate of bile leak (7/18 vs. 3/21, P = 0.039) than those who underwent ORAS. However, there was no significant difference in the operative time (174 ± 39 vs. 198 ± 60 min, P = 0.156), transfusion rate (3/18 vs. 6/21, P = 0.316), or hospital expense (5.7 ± 0.9 vs. 6.0 ± 1.3 Wan RMB, P = 0.511) between the LRAS and ORAS groups. Furthermore, the frequency and intensity of other complications (P > 0.05), postoperative white blood cell count (11.9 ± 3.0 vs. 12.7 ± 2.9 109/L, P = 0.431), aspartate aminotransferase level (92 [range, 123–241] vs. 173 [range, 86–256] U/L, P = 0.587), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level (206 [range, 150–247] vs. 137 [106–267] U/L, P = 0.364) were not significantly different between the two groups.

Survival and recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

There was no statistically significant difference in the disease-free survival (P = 0.351) or overall survival (P = 0.613) between the LRAS and ORAS groups (Fig. 4).

Discussion

LRAS is one of the most technically challenging procedures due to the complicated anatomy of the liver pedicle, the extensive resection required in two planes, and easy bleeding13. Furthermore, studies on LRAS are limited to case reports or small series14,15,16. Thus, in this study, we aimed to explored and summarized the benefits and drawbacks of LRAS and compared them with those of ORAS. Our results showed that LRAS is safe and feasible.

In our study, patients who underwent LRAS had significantly lesser blood loss than those who underwent ORAS. This finding was consistent with those of previous studies on laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy7, right hemihepatectomy8, right posterior sectionectomy9, caudate lobe resection10,11, and LRAS17. Furthermore, the intraoperative blood loss associated with LRAS in our study was similar to that in the study by Deng et al.14 and Livin et al.15. Furthermore, bleeding control was superior during LH that during open hepatectomy. This may be attributable to the improved intraoperative magnification for surgical manipulations and the pressure associated with pneumoperitoneum18,19,20. Nonetheless, irrespective of the approach used, occasional bleeding and hepatic vein injury are the most common risks associated with hepatectomy. Thus, detailed preoperative evaluations, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, 3D reconstruction, and intraoperative ultrasonography, are essential to accurately determine the size and location of the lesion and understand the individual variations in the blood vessels and biliary tract, which will aid in reducing the bleeding risk21,22,23. Furthermore, over time, the effective and professional knowledge of surgeons has improved their technical skills, giving them more confidence to perform surgeries and contributing to the standardization of surgical procedures. The operative time of laparoscopic right hemihepatectomy8 and central hepatectomy24 is longer than that of caudate lobe resection10,11. However, differences in the operative time between laparoscopic and open surgery for right posterior sectionectomy9, left lateral hepatic sectionectomy6, and left hemihepatectomy7 were not observed, which is partly consistent with the results of previous studies. Similarly, in our study, there was no difference in operative time between LRAS and ORAS. This may be a reflection of the technological progress of surgeons. And the rapid development and progress of laparoscopic equipment, such as Endo GIA stapler, have significantly shortened surgical time and effectively prevented bleeding25. Moreover, consistent with the results of previous studies on left lateral lobectomy, right posterior sectionectomy, and caudate lobe resection7,9,10,11, our study results demonstrate that there is no significant difference in costs between open and laparoscopic surgeries for right anterior sectionectomy, but the patients who underwent LRAS had a shorter hospital stay than those who underwent ORAS. This finding was consistent with those of previous studies on right anterior sectionectomy and central hepatectomy24,25. Furthermore, although laparoscopic materials (e.g., laparoscopes, trocars, Hem-o-lok clips, and staplers) increase the hospital costs of LRAS18,26,27, shorter surgical time and fewer hospital stays are enough to offset these costs.

In our study, patients who underwent LRAS demonstrated a higher bile leakage rate than those who underwent ORAS, which is partially consistent with the rates in patients who have undergone left and right hemihepatectomies7,8. However, the bile leakage rate in our study was higher than that in the study by Ide et al.16. The lower complication rate in the ORAS group may be attributable to the routine administration of water injections into the cystic tube to detect the presence of bile leakage; this was not performed in patients who underwent LRAS. There was no significant difference in the rate of other complications between the ORAS and LRAS groups in our study. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the surgical margins and the postoperative levels of ALT, albumin, and total bilirubin between the ORAS and LRAS groups. This indicated that there was no difference in the extent of perioperative liver injury or functional outcomes between the study groups. In our study, the surgical method used did not affect the prognosis of patients with HCC, which is consistent with the results of previous studies9,28.

Owing to the special location and anatomical characteristics of the right anterior lobe, LRAS can be challenging. The pedicle of the right anterior lobe runs deep in the liver parenchyma, making its exposure difficulty. To overcome this, precise preoperative three-dimensional visualization is required for evaluating the anatomical structure of the liver in detail. Furthermore, intraoperative ultrasonography is required to guide the dissection of the liver parenchyma along the hepatic portal plate up to the right anterior lobe pedicle. Another challenge of LRAS is the thick diameter and numerous tributaries of the MHV and RHV, which are the main reflux veins of the liver. These tributaries should be identified, followed by the trunk of the branches. During hepatic transection, the RHV and MHV tributaries should be ligated in the deepest portions of the liver to avoid substantial hemorrhage. LRAS involves the resection of two liver segments, dissection of substantial liver parenchyma, and processing of numerous branches. Thus, the MHV and RHV can be used as an intrahepatic landmark to guide the liver resection margins. Furthermore, intraoperative Indocyanine Green fluorescence staining can help identify the appropriate resection plane29. Finally, the good intraoperative CVP control can reduce intraoperative bleeding and enhance surgeon confidence30.

This study has some limitations. First, the time period during which the two surgeries were performed were different. We first performed RAS, and after the advancements in technology, LRAS was performed. Second, this study was a retrospective study with limited evidence. Thus, prospective studies are required to validate our findings. Third, this was a single center study with a relatively small population sample. Future studies should include large samples from multiple centers.

In conclusion, our study results demonstrate that laparoscopy is suitable for right anterior sectionectomy. In the era of minimally invasive surgical, we hope more patients can benefit from it.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Jeong, J. S., Gwak, M. S., Kim, G. S., Ko, J. S. et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between pure laparoscopic surgery and open right hepatectomy in living donor hepatectomy: propensity score matching analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 5314 (2020).

Yukiyasu Okamura, Y. et al. Novel patient risk factors and validation of a difficulty scoring system in laparoscopic repeat hepatectomy. Sci. Rep. Volume. 9, 17653 (2019).

Abu Hilal, M. et al. Assessment of the financial implications for laparoscopic liver surgery: a single-centre UK cost analysis for minor and major hepatectomy. Surg. Endosc. 27, 2542–2550 (2013).

Nguyen, K. T., Gamblin, T. C. & Geller, D. A. World review of laparoscopic liver resection-2,804 patients. Ann. Surg. 250, 831–841 (2009).

Dagher, I. et al. Laparoscopic major hepatectomy: an evolution in standard of care. Ann. Surg. 250, 856–860 (2009).

Liu, Z., Ding, H., Xiong, X. & Huang, Y. Laparoscopic left lateral hepatic sectionectomy was expected to be the standard for the treatment of left hepatic lobe lesions: a meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 97, e9835 (2018).

Yin, X., Luo, D., Huang, Y. & Huang, M. Advantages of laparoscopic left hemihepatectomy: A meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 98, e15929 (2019).

Xin, Y., Luo, D., Tang, Y., Huang, M. & Huang, Y. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopy technology in right hemihepatectomy. Sci. Rep. 9, 18809 (2019).

Luo, D. et al. The Safety and Feasibility of Laparoscopic Technology in right posterior sectionectomy. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc Percutan Tech. 30, 169–172 (2020).

Ding, Z. et al. Comparative analysis of the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic versus open caudate lobe resection. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 405, 737–744 (2020).

Ding, Z. et al. Safety and feasibility for laparoscopic versus open caudate lobe resection: a meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 406, 1307–1316 (2021).

Daisuke Ban, M., Katagiri, T., Takagi, C., Itano, O., Kaneko, H., Wakabayashi, G. et al. A novel difficulty scoring system for laparoscopic liver resection. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 21, 745–753 (2014).

Goro Honda, M., Kurata, Y., Okuda, S., Kobayashi, K. & Sakamoto, K. T. Totally laparoscopic anatomical hepatectomy exposing the major hepatic veins from the Root side: a case of the right anterior sectorectomy (with video). J. Gastrointest. Surg. 18, 1379–1380 (2014).

Haowen Deng, X. & Zeng, N. X. Augmented reality Navigation System and Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging make laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy more precisely and safely. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 27, 1751–1752 (2023).

Marie Livin, A. et al. Combination of a Glissonean Approach and Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging to perform a laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31, 4030 (2024).

Ide, T., Matsunaga, T., Tanaka, T. & Noshiro, H. Feasibility of purely laparoscopic right anterior sectionectomy. Surg. Endosc. 35, 192–199 (2021).

Jeung, I. H., Choi, S. H., Kim, S. & Kwon, S. W. Laparoscopic Central Bisectionectomy and Right Anterior Sectionectomy using two retraction methods: Technical aspects with video. World J. Surg. 43, 3120–3127 (2019).

Morino, M., Morra, I., Rosso, E., Miglietta, C. & Garrone, C. Laparoscopic vs open hepatic resection: A comparative study. Surg. Endosc. 17, 1914–1918 (2003).

Morise, Z. et al. Pure laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma with chronic liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 5, 487 (2013).

Dagher, I. et al. Laparoscopic versus open right hepatectomy: A comparative study. Am. J. Surg. 198, 173–177 (2009).

Chihua Fang, J. et al. Consensus recommendations of three-dimensional visualization for diagnosis and management of liver diseases. Hepatol. Int. 14, 437–453 (2020).

Araki, Z., Conrad, K. & Ogiso, C. Intraoperative ultrasonography of laparoscopic hepatectomy: Key technique for safe liver transection. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 218, e37–41 (2014).

Ricky Jrearz, R. & Hart, S. Intraoperative ultrasonography and surgical strategy in hepatic resection: What difference does it make? Can. J. Surg. 58, 318–322 (2015).

Chin, K. M., Chan, C. Y., Goh, B. K. P. Minimally invasive versus open right anterior sectionectomy and central hepatectomy for central liver malignancies: A propensity-score-matched analysis. ANZ J. Surg. 91, E174–E182 (2021).

Schemmer, P. et al. The use of endo-GIA vascular staplers in liver surgery and their potential benefit: A review. Dig. Surg. 24, 300–305 (2007).

Medbery, R. L. et al. Laparoscopic vs open right hepatectomy: A value-based analysis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 218, 929–939 (2014).

Polignano, F. M. et al. Laparoscopic versus open liver segmentectomy: Prospective, case-matched, intention-to-treat analysis of clinical outcomes and cost effectiveness. Surg. Endosc. 22, 2564–2570 (2008).

Rhu, J. et al. Laparoscopic versus open right posterior sectionectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in a high volume center: A propensity score matched analysis. World J. Surg. 42, 2930–2937 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided laparoscopic hepatectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-center propensity score matching study. Front. Oncol. 12, 930065 (2022).

Montorsi, M. et al. Perspectives and draw backs of minimally invasive surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 49, 56–61 (2002).

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81760514).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wen Li, Yong Huang wrote the main manuscript text and Wen Li, Yong Huang prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Revised manuscript: Haitao Zeng, Yong Huang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Zeng, H. & Huang, Y. Comparative analysis of the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic and open approaches for right anterior sectionectomy. Sci Rep 14, 30185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80148-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80148-0